Kahoolawe

| Kahoʻolawe | |

|---|---|

| The Target Isle | |

Landsat satellite image of Kahoʻolawe. |

|

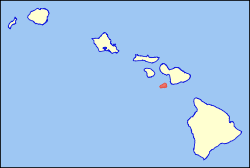

Location in the state of Hawaiʻi. |

|

| Geography | |

| Location | , Maui County, Hawaii |

| Area | 44.6 sq mi (115.5 km²) |

| Rank | 8th largest Hawaiian Island |

| Highest point | Puʻu Moaulanui (Lua Makika) |

| Max elevation | 1,483 ft (452 m)[1] |

| Demographics | |

| Population | Uninhabited |

| Official Insignia | |

| Flower | Hinahina kū kahakai (Heliotropium anomalum var. argenteum)[2] |

| Color | ʻĀhinahina (gray) |

Kahoʻolawe (pronounced /kəˌhoʊ.əˈlɑːwi/ in English and [kəˈhoʔoˈlɐve] in Hawaiian) is the smallest of the eight main volcanic islands in the Hawaiian Islands. It is located 7 miles (11.2 km) southwest of Maui and southeast of Lānaʻi and is 11 miles (18 km) long by 6 miles (9.7 km) wide, with a total area of 44.6 square miles (115.5 km2).[3] The highest point is the crater of Lua Makika at the summit of Puʻu Moaulanui, which is 1,477 feet (450 m) above sea level. The island is relatively dry (average annual rainfall is less than 65 cm/26 in)[4] because the low elevation fails to generate much orographic precipitation from the northeastern trade winds and it is located in the rain shadow of east Maui's 10,023 feet (3,055 m) high volcano, Haleakalā. More than one quarter of Kahoʻolawe has been eroded down to saprolitic hardpan.

Kahoʻolawe has always been sparsely populated, due to a lack of freshwater. Beginning in World War II, the island was used as a training ground and bombing range by the United States military. After decades of protests, the Navy ended live-fire training on Kahoʻolawe in 1990, and the island was transferred to the State of Hawaii in 1994. The Hawaii State Legislature established the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve to restore and oversee the island and its surrounding waters. Today Kahoʻolawe can be used only for native Hawaiian cultural, spiritual, and subsistence purposes.

The United States Census Bureau defines Kahoʻolawe as Block Group 9, Census Tract 303.02 of Maui County, Hawaiʻi. The island has no permanent residents.[5]

Contents |

History

Settlement

Sometime around 1000, Kahoʻolawe was settled, and small, temporary fishing communities were established along the coast. Some inland areas were cultivated. Puʻu Moiwi, a remnant cinder cone,[6] is home to the second largest basalt quarry in the archipelago, which was mined for use in tools such as koʻi (adzes).[7] Originally a dry forest environment with intermittent streams, the land changed to an open savanna of grassland and trees when inhabitants cleared vegetation for firewood and agriculture.[8] Hawaiians built stone platforms for religious ceremonies, set rocks upright as shrines for successful fishing trips, and carved petroglyphs, or drawings, into the flat surfaces of rocks. These indicators of an earlier time can still be found on Kahoʻolawe.

While it is not known how many people inhabited the island, the lack of freshwater probably limited the population to a few hundred. As many as 100 or more people may have once lived at Hakioawa, the largest settlement located at the northeast end of the island facing Maui.

Warfare

Violent wars among competing aliʻi (chiefs) laid waste to the land and led to a decline in the population. During the War of Kamokuhi, Kalaniʻōpuʻu, the ruler of the Island of Hawaiʻi, raided and pillaged Kahoʻolawe in an unsuccessful attempt to take Maui from Kahekili II, the King of Maui.[9]

Post-contact

From 1778 to the early 1800s, observers on passing ships reported that the island was uninhabited and barren, destitute of both water and wood. After the arrival of missionaries from New England, the Hawaiian government of King Kamehameha III replaced the death penalty with exile, and Kahoʻolawe became a male penal colony sometime around 1830. Food and water were scarce, some prisoners reportedly starved, and some swam across the channel to Maui to find food. The law making the island a penal colony was repealed in 1853.

An 1857 survey of Kahoʻolawe reported about 50 residents, about 5,000 acres (20 km2) of land covered with shrubs, and a patch of sugarcane. Along the shore, tobacco, pineapple, gourds, pili grass and scrub trees grew. Beginning in 1858, the Hawaiian government leased Kahoʻolawe to a sequence of ranching ventures. Some proved more successful than others, but the lack of freshwater was an unyielding enemy. Through the next 80 years, the landscape changed dramatically—drought and uncontrolled overgrazing denuded much of the island. Strong trade winds blew away most of the topsoil, leaving behind red hardpan.

20th century

From 1910 to 1918, the Hawaiian Territorial government designated Kahoʻolawe as a forest reserve in hopes of restoring the island through a revegetation and livestock removal program. The program failed and leases again became available. In 1918, the Wyoming rancher Angus MacPhee, with the help of Maui landowner Harry Baldwin, leased the island for 21 years, intending to build a cattle ranch. By 1932, the ranching operation was enjoying moderate success. After heavy rains, native grasses and flowering plants would sprout, but drought seemed to always return. In 1941, MacPhee sublet part of the island to the United States Army. Later that year, because of continuing drought, MacPhee removed his cattle from the island.

Training grounds

On December 8 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Army declared martial law throughout Hawaiʻi and utilized Kahoʻolawe as a place to train Americans headed to war across the Pacific. The use of Kahoʻolawe as a bombing range was believed to be critical to the lives of many young Americans, as the United States was executing a new type of war in the Pacific Islands. Success depended on accurate naval gunfire support that suppressed enemy positions as Marines and soldiers struggled to get ashore. Thousands of soldiers, sailors, Marines and airmen prepared on Kahoʻolawe for the brutal and costly assaults on islands such as the Gilberts, the Marianas and Iwo Jima.

Training on Kahoʻolawe continued after World War II. During the Korean War, carrier-based aircraft played a critical role in attacking enemy airfields, convoys and troop staging areas. Mock-ups of airfields, vehicles and other camps were constructed on Kahoʻolawe, and while pilots were undergoing readiness inspection at nearby Barbers Point Naval Air Station, they practiced spotting and hitting the mock-ups at Kahoʻolawe. Similar training took place through the Cold War and during Vietnam, as mock-ups of aircraft, radar installations, gun mounts and surface-to-air missile sites were placed across the island for pilots and others to use for training.

In early 1965, the United States Navy conducted Operation Sailor Hat to determine the blast resistance of ships. Three tests off the coast of Kahoʻolawe subjected the island and a target ship to massive explosions, with 500 tons of conventional TNT detonated on the island near the target ship USS Atlanta (CL-104); The ship was damaged, but not sunk. The blasts created a crater on the island known as "Sailor Man's Cap" and may have cracked the island's caprock, causing valuable groundwater to be lost into the ocean.[10]

Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (PKO)

In 1976, a group of individuals calling themselves the Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (PKO) filed suit in federal court to stop the Navy’s use of Kahoʻolawe for military training, to require compliance with a number of new environmental laws and to ensure protection of cultural resources on the island. In 1977, the United States District Court for the District of Hawaii allowed the Navy’s use of the island to continue, but the Court directed the Navy to prepare an environmental impact statement and complete an inventory of historic sites on the island. On 9 March 1977, two PKO leaders, George Helm and Kimo Mitchell, were lost at sea during an attempt to occupy Kahoʻolawe in symbolic protest. In 1980, the Navy and the Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana entered into a consent decree which allowed continued military training on the island, monthly access to the island for the PKO, surface clearance of part of the island, soil conservation, feral goat eradication and an archaeological survey.

Kahoʻolawe Island Archeological District

| Kahoʻolawe Island Archeological District | |

|---|---|

| U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

| U.S. Historic District | |

| Added to NRHP: | March 18, 1981 |

| NRHP Reference#: | 81000205 |

On 28 March 1981, the entire island was added to the National Register of Historic Places. At that time, the Kahoʻolawe Archaeological District was noted to contain 544 recorded archaeological or historic sites and over 2,000 individual features. As part of the soil conservation efforts, Mike Ruppe and other workers laid lines of explosive charges, detonating them to break the hardpan so that seedling trees could be planted. Used tires were taken to Kahoʻolawe and placed in miles of deep gullies to slow the washing of red soil from the barren uplands to the surrounding shores. Ordnance and scrap metal was picked up by hand and transported by large trucks to a collection site.

End of live-fire training

In 1990, President George H. W. Bush ordered an end to live-fire training on the island. The Department of Defense Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 1991 established the Kahoʻolawe Island Conveyance Commission to recommend terms and conditions for the conveyance of Kahoʻolawe by the United States government to the State of Hawaiʻi.

Transfer of title and UXO cleanup

In 1993, Senator Daniel Inouye of Hawaiʻi sponsored Title X of the Fiscal Year 1994 Department of Defense Appropriations Act, directing that the United States convey Kahoʻolawe and its surrounding waters to the State of Hawaiʻi. Title X also established the objective of a “clearance or removal of unexploded ordnance (UXO)” and environmental restoration of the island, to provide “meaningful safe use of the island for appropriate cultural, historical, archaeological, and educational purposes, as determined by the State of Hawaii.” In turn, the State created the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission to exercise policy and management oversight of the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve. As directed by Title X and in accordance with a required United States Navy/State of Hawaiʻi Memorandum of Understanding, the Navy transferred title of Kahoʻolawe to the State of Hawaiʻi on 9 May 1994.

As required by Title X, the Navy retained access control to the island until clearance and environmental restoration activities were completed, or November 11, 2003, whichever came first. The State agreed to prepare a Use Plan for Kahoʻolawe and the Navy agreed to develop a Cleanup Plan based on that use plan and to implement that plan to the extent Congress provided funds for that purpose.

In July 1997, the Navy awarded a contract to the Parsons/UXB Joint Venture to clear ordnance from the island to the extent funds were provided by Congress. After the State and public review of the Navy cleanup plan, Parsons/UXB began their work on the island in November 1998.

The Navy attempted a cleanup of the unexploded ordnance from the island, although much still remains buried or resting on the land surface. Other items have washed down gullies and still others lie beneath the waters offshore. The turnover was officially made on November 11, 2003, but the cleanup was not completed. Although the U.S. Navy was given $400 million and 10 years to complete the task, work progressed much more slowly than anticipated. As of the time of turnover, access to Kahoʻolawe requires escort and careful attention within areas known to contain unexploded ordnance.

Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve

In 1993, the Hawaiʻi State Legislature established the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve, consisting of "the entire island and its surrounding ocean waters in a two mile (3 km) radius from the shore". By State Law, Kahoʻolawe and its waters can only be used for Native Hawaiian cultural, spiritual and subsistence purposes; fishing; environmental restoration; historic preservation; and education. Commercial uses are prohibited.

The Legislature also created the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC) to manage the Reserve while it is held in trust for a future Native Hawaiian Sovereignty entity. The restoration of Kahoʻolawe will require a strategy to control erosion, re-establish vegetation, recharge the water table, and gradually replace alien plants with native species. Plans will include methods for damming gullies and reducing rainwater runoff. In some areas, non-native plants will temporarily stabilize soils before planting of permanent native species. Species used for revegetation include ʻaʻaliʻi (Dodonaea viscosa), ʻāheahea (Chenopodium oahuense), kuluʻī (Nototrichium sandwicense), Achyranthes splendens, ʻūlei (Osteomeles anthyllidifolia), kāmanomano (Cenchrus agrimonioides var. agrimonioides), koaiʻa (Acacia koaia), and alaheʻe (Psydrax odorata).[12]

See also

- ʻAlalākeiki Channel

- Vieques, Puerto Rico

References

- ↑ "Table 5.11 - Elevations of Major Summits" (PDF). 2004 State of Hawaii Data Book. State of Hawaii. 2004. http://www.hawaii.gov/dbedt/info/economic/databook/db2004/section05.pdf. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ↑ Shearer, Barbara Smith (2002). "Chapter 6 - State and Territory Flowers". State Names, Seals, Flags, and Symbols: a Historical Guide (3 ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 99. ISBN 9780313315343. http://books.google.com/?id=nCA0UuGlJG8C.

- ↑ "Table 5.08 - Land Area of Islands: 2000" (PDF). 2004 State of Hawaii Data Book. State of Hawaii. 2004. http://www.hawaii.gov/dbedt/info/economic/databook/db2004/section05.pdf. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ↑ "Kahoʻolawe". Hawaii's Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy. Hawaii Division of Land and Natural Resources. http://www.state.hi.us/dlnr/dofaw/cwcs/files/NAAT%20final%20CWCS/Chapters/CHAPTER%206%20kahoolawe%20NAAT%20final%20!.pdf. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- ↑ Block Group 9, Census Tract 303.02, Maui County United States Census Bureau

- ↑ Macdonald, Gordon Andrew; Agatin Townsend Abbott; Frank L. Peterson (1983). Volcanoes in the Sea: the Geology of Hawaii (2 ed.). University of Hawaii Press. p. 401. ISBN 9780824808327.

- ↑ McGregor, Davianna (2007). "Chapter 6 - Kahoʻolawe: Rebirth of the Sacred". Nā Kuaʻāina: Living Hawaiian Culture. University of Hawaii Press. p. 253. ISBN 9780824829469. http://books.google.com/?id=brPxqIxh3JYC.

- ↑ Merlin, Mark D.; James O. Juvik (1992). Charles P. Stone; Clifford W. Smith; J. Timothy Tunison. ed. Alien Plant Invasions in Native Ecosystems of Hawaii: Management and Research. p. 602. http://www.hear.org/books/apineh1992/pdfs/apineh1992vi1merlinjuvik.pdf.

- ↑ Fornander, Abraham (1880). An Account of the Polynesian Race: Its Origins and Migrations, and the Ancient History of the Hawaiian People to the Times of Kamehameha I. London: Trübner & Co. pp. 156–157. http://books.google.com/?id=tcQNAAAAQAAJ.

- ↑ Sarhangi, Sheila (November 2006). "Saving Kahoʻolawe". Honolulu Magazine (PacificBasin Communications). http://www.honolulumagazine.com/Honolulu-Magazine/November-2006/Saving-Kaho-8216olawe/.

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2008-04-15. http://www.nr.nps.gov/.

- ↑ Enomoto, Kekoa Catherine (2008-02-17). "Volunteers visit regreened Kahoolawe". The Maui News. http://www.mauinews.com/page/content.detail/id/500475.html. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

Further reading

- Coffman, Tom (2003). The Island Edge of America: A Political History of Hawai'i. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0824826620.

- Juvik, Sonia P.; James O. Juvik, Thomas R. Paradise (1998). Atlas of Hawaii. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824821258.

- Levin, Wayne; Roland B. Reeve (1995). Kaho'olawe Na Leo O Kanaloa: Chants and Stories of Kaho'olawe. ʻAi Pohaku Press. ISBN 1883528011.

- MacDonald, Peter (1972). "Fixed in Time: A Brief History of Kahoolawe". Hawaiian Journal of History (Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society) 6: 69–90. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/6328.

- Napier, A. Kam (November 2006). "On Kahoʻolawe". Honolulu Magazine (PacificBasin Communications). http://www.honolulumagazine.com/Honolulu-Magazine/November-2006/On-Kaho-8216olawe/.

- Ritte Jr., Walter; Richard Sawyer (1978). Na Manaʻo Aloha O Kahoʻolawe. Honolulu: Aloha ʻAina O Na Kupuna, Inc..

- Sano, H; Sherrod, D; Tagami, T (2006). "Youngest volcanism about 1 million years ago at Kahoolawe Island, Hawaii". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research (PacificBasin Communications) 152 (1-2): 91–96. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2005.10.001.

- Tavares, Hannibal M.; Noa Emmett Aluli, A. Frenchy DeSoto, James A. Kelly, H. Howard Stephenson (1993). Kaho'olawe Island: Restoring a Cultural Treasure. Final Report of the Kaho'olawe Island Conveyance Commission to the Congress of the United States. Kaho'olawe Island Conveyance Commission.

External links

- Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission

- Hawaiian Encyclopedia:Kahoʻolawe

- Navy Region Hawaiʻi Kahoʻolawe Ordnance Removal Operation

- Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana organization website

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||