John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough

| John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough | |

|---|---|

| 26 May 1650 – 16 June 1722 (aged 72)[1] | |

.jpg) The Duke of Marlborough. Oil by Adriaen van der Werff. |

|

| Place of birth | Ashe House, Devon |

| Place of death | Windsor Lodge |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | |

| Battles/wars | Monmouth Rebellion • Battle of Sedgemoor Nine Years' War • Battle of Walcourt War of the Spanish Succession • Battle of Schellenberg • Battle of Blenheim • Battle of Elixheim • Battle of Ramillies • Battle of Oudenarde • Siege of Lille • Battle of Malplaquet • Siege of Bouchain |

| Awards | Order of the Garter |

John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, Prince of Mindelheim, KG, PC (26 May 1650 – 16 June 1722) (O.S),[1] was an English soldier and statesman whose career spanned the reigns of five monarchs through the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Rising from a lowly page at the court of the House of Stuart, he loyally served the Duke of York through the 1670s and early 1680s, earning military and political advancement through his courage and diplomatic skill. Churchill's role in defeating the Monmouth Rebellion in 1685 helped secure James on the throne, yet just three years later he abandoned his Catholic patron for the Protestant Dutchman, William of Orange. Honoured for his services at William's coronation with the earldom of Marlborough (pronounced /'mɔ:l bəɹə/), he served with further distinction in the early years of the Nine Years' War, but persistent charges of Jacobitism brought about his fall from office and temporary imprisonment in the Tower. It was not until the accession of Queen Anne in 1702 that Marlborough reached the zenith of his powers and secured his fame and fortune.

His marriage to the hot-tempered Sarah Jennings – Anne's intimate friend – ensured Marlborough's rise, first to the Captain-Generalcy of British forces, then to a dukedom. Becoming de facto leader of Allied forces during the War of the Spanish Succession, his victories on the fields of Blenheim (1704), Ramillies (1706), Oudenarde (1708), and Malplaquet (1709), ensured his place in history as one of Europe's great generals. But his wife's stormy relationship with the Queen, and her subsequent dismissal from court, was central to his own fall. Incurring Anne's disfavour, and caught between Tory and Whig factions, Marlborough, who had brought glory and success to Anne's reign, was forced from office and went into self-imposed exile. He returned to England and to influence under the House of Hanover with the accession of George I to the British throne in 1714, but following a series of strokes in later age his health gradually deteriorated, and he died on 16 June 1722 (O.S), at Windsor Lodge.

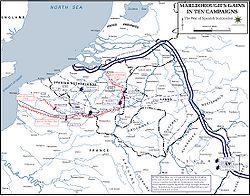

Marlborough's insatiable ambition propelled him from poor obscurity to prominence in British and European affairs, becoming the richest of all Anne's subjects. His family connections wove him into the fabric of European politics (his sister Arabella became James II's mistress, and their son, the Duke of Berwick, emerged as one of Louis XIV's greatest Marshals). Throughout ten consecutive campaigns during the Spanish Succession war Marlborough held together a discordant coalition through his sheer force of personality and raised the standing of British arms to a level not known since the Middle Ages. Although in the end he could not extort total capitulation from his enemies, his victories allowed Britain to rise from the periphery of influence to major power status, thus ensuring the country's growing prosperity throughout the 18th century.

Contents |

Early life (1650–78)

Ashe House

At the end of the English Civil War Lady Eleanor Drake was joined at her Devon home, Ashe House in the parish of Musbury, by her third daughter Elizabeth, and Elizabeth's husband, Winston Churchill. Unlike his mother-in-law who had supported the Parliamentary cause, Winston had had the misfortune of fighting on the losing side of the war for which he, like so many other Cavaliers, was forced to pay recompense; in his case £446 18s.[2] Although Winston had paid off the fine by 1651, it had impoverished the ex-Royalist cavalry captain whose motto Fiel Pero Desdichado (Faithful but Unfortunate) is still today used by his descendants.

Winston and Elizabeth Churchill had at least nine children, only five of whom survived infancy.[3] The eldest daughter, Arabella, was born on 28 February 1649;[4] the eldest son, John, was born on 26 May 1650 (O.S). They had two younger brothers: George (1654–1710), who later became an admiral in the Royal Navy; and Charles (1656–1714), who became a general and later served on campaign in Europe with John. However, little is known of John Churchill's childhood for he himself tells us nothing of it, but growing up in these impoverished conditions at Ashe, with family tensions soured by conflicting allegiances, may have had a lasting impression on the young Churchill. His father's namesake, and John Churchill's biographer and descendant, Sir Winston Churchill, asserted – "[The conditions at Ashe] might well have aroused in his mind two prevailing impressions: First a hatred of poverty ... and secondly, the need of hiding thoughts and feelings from those to whom their expression would be repugnant."[5]

After the Restoration of King Charles II in 1660 the elder Churchill's fortunes took a turn for the better, although he remained far from prosperous.[6] In 1661, Winston became Member of Parliament for Weymouth, and as a mark of royal favour he received rewards for losses incurred fighting Parliament during the civil war, including the appointment as a Commissioner for Irish Land Claims in Dublin in 1661. When Winston departed for Ireland the following year, John enrolled at the Dublin Free School; but by 1664, following his father's recall to the position of Junior Clerk Comptroller of the King's Household at Whitehall, John had transferred his studies to St Paul's School in London. The King's own penury meant the old Cavaliers received scant financial reward, but what the prodigal monarch could offer – which would cost him nothing – were positions at court for their progeny. So it was that in 1665 Arabella became Maid of Honour to Anne Hyde, the Duchess of York, joined some months later by her brother John, as page to her husband, James, Duke of York.[7]

Early military experience

.png)

The Duke of York's passion for all things naval and military rubbed off on young Churchill. Often accompanying the Duke inspecting the troops in the royal parks, it was not long before the boy had set his heart on becoming a soldier himself.[8] On 14 September 1667 (O.S), he obtained a commission as ensign in the King's Own Company in the 1st Guards, later to become the Grenadier Guards.[9] His career advanced further when in 1668 Churchill sailed for the North African outpost of Tangier, recently acquired as part of the dowry of Charles II's Portuguese wife, Catherine of Braganza. In a rude contrast to life at court, Churchill stayed here for three years, gaining first-class tactical training and field experience skirmishing with the Moors.[10]

Back in London by February 1671, Churchill's handsome features and manner – described by Lord Chesterfield as "irresistible to either man or woman" – had soon attracted the ravenous attentions of one of the King's most noteworthy mistresses, Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland.[11] But his liaisons with the insatiable temptress were indeed dangerous. One account has it that upon His Majesty's appearance Churchill leapt out of his lover's bed and hid in the cupboard, but the King, himself wily in such matters, soon discovered young Churchill who promptly fell to his knees – "You are a rascal," said Charles, "but I forgive you because you do it to get your bread."[12] The story may be apocryphal (another version has Churchill jumping out of the window), yet it is widely accepted that he was the father of Cleveland's daughter, Barbara, born on 16 July 1672 (O.S).[13]

In 1672 Churchill went to sea again. While fighting the Dutch navy at the Battle of Solebay off the Suffolk coast in June, valorous conduct aboard the Duke of York's flagship, the Prince, earned Churchill promotion (above the resentful heads of more senior officers) to a captaincy in the Admiralty Regiment.[15] The following year Churchill gained a further commendation at the Siege of Maastricht when the young captain distinguished himself as part of the 30-man forlorn hope, successfully capturing and defending part of the fortress. During this incident Churchill is credited with saving the Duke of Monmouth's life, receiving a slight wound in the process but gaining further praise from a grateful House of Stuart, as well as recognition from the House of Bourbon. King Louis XIV in person commended the deed, from which time forward bore Churchill an enviable reputation for physical courage, as well as earning the high regard of the common soldier.[16]

Although Charles II's anti-French Parliament had forced England to withdraw from the Franco-Dutch War in 1674, some English regiments remained in French service. In April Churchill was appointed the colonelcy of one such regiment, thereafter serving with, and learning from, the great Marshal Turenne. Churchill was present at the hard-fought battles of Sinsheim in June 1674, and Ensheim in October; he may also have been present at Sasbach in July 1675, where Turenne was killed.[17]

Marriage

On his return to St. James's Palace, Churchill's attention was drawn towards other matters, and to a fresh face at court. "I beg you will let me see you as often as you can," pleaded Churchill in a letter to Sarah Jennings, "which I am sure you ought to do if you care for my love ..."[18] Sarah Jennings' social origins were in many ways similar to Churchill's – minor gentry blighted by debt-induced poverty. After her father died when she was eight, Sarah, together with her mother and sisters, moved to London. As Royalist supporters (despite the fact that Sarah's great uncle, James Temple, was convicted of regicide), the Jennings' loyalty to the crown, like the Churchill's, was repaid with court employment, and in 1673 Sarah followed her sister Frances into the household of the Duchess of York, Mary of Modena, second wife to James, Duke of York.[19]

Sarah was about fifteen when Churchill returned from the Continent in 1675, and he appears to have been almost immediately captivated by her charms and considerable good looks.[18] Churchill's amorous, almost abject, missives of devotion were, it seems, received with suspicion – his first lover, Barbara Villiers, was just moving her household to Paris, feeding doubts that he may well have been looking at Sarah as a replacement mistress rather than a fiancée.[20] However, his persistent courtship over the coming months eventually won over the beautiful, if relatively poor, Maid of Honour. Although Winston wished his son to marry the wealthy Catherine Sedley (if only to ease his own burden of debt), Colonel Churchill married Sarah sometime in the winter of 1677–78, possibly in the apartments of the Duchess of York.[21]

Years of crises (1678–1700)

Diplomatic service

Under the Earl of Danby the government now undertook a political realignment, and prepared to enter the war against France. The new alliance with the Dutch, together with the expansion of the English army, opened important prospects for Churchill in military and diplomatic spheres. In April 1678, Churchill (accompanied by his friend and rising politician, Sidney Godolphin), departed for The Hague to negotiate a convention on the deployment of the English army in Flanders. The young diplomat's essay in international statecraft proved personally successful, bringing him into contact with William, Prince of Orange, who was highly impressed by the shrewdness and courtesy of Churchill's negotiating skills.[22] The assignment had helped Churchill develop a breadth of experience that other mere soldiers were never to achieve,[22] yet because of the duplicitous dealings of Charles II's secret negotiations with Louis XIV (Charles had no intention of waging war against France), the mission ultimately proved abortive. In May, Churchill was appointed temporary rank of Brigadier-General of Foot, but hopes of promised action on the Continent proved illusory as the warring factions sued for peace and signed the Treaty of Nijmegen.[23]

When Churchill returned to England at the end of 1678 he found grievous changes in English society. The iniquities of the Popish Plot (Titus Oates' fabricated conspiracy aimed at excluding the Catholic Duke of York from the English accession), meant temporary banishment for James – an exile that would last nearly three years. James obliged Churchill to attend him, first to The Hague then to Brussels, before gaining permission to move to Edinburgh. Yet it was not until 1682, after Charles II's complete victory over the exclusionists, that the Duke of York was allowed to return to London.[24] For his services during the crisis Churchill was made Lord Churchill of Eyemouth in the peerage of Scotland on 21 December 1682 (O.S), and the following year, on 19 November (O.S), appointed colonel of the King's Own Royal Regiment of Dragoons.[25]

The Churchills' combined income now ensured a life of some style and comfort; as well as maintaining their residence in London (staffed with seven servants), they were also able to purchase Holywell House in St Albans (Sarah Jennings' family home) where their own family could enjoy the benefits of country life. While in Edinburgh Sarah had given birth to Henrietta on 19 July 1681 (O.S). Another daughter, Anne, arrived in 1684, followed by John in 1686, Elizabeth in 1687, Mary in 1689, and Charles in 1690 who lived for only two years.[26]

Churchill resumed court life with enthusiasm. In July 1683 he was sent to the Continent to conduct Prince George of Denmark to England for his arranged marriage to the 18-year-old Princess Anne, the Duke of York's younger daughter. Anne lost no time in appointing Sarah – of whom she had been passionately fond since childhood – one of her Ladies of the Bedchamber. Their relationship continued to blossom, so much so that years later Sarah wrote – "To see [me] was a constant joy; and to part with [me] for never so short a time, a constant uneasiness ... This worked even to the jealousy of a lover."[27] For his part, Churchill treated the princess with respectful affection and grew genuinely attached to her, assuming – in his reverence to royalty – the chivalrous role of a knightly champion.[28] From this time forward the Churchills were increasingly detached from James's Catholic inner circle and more noticeably associated with the Princess.[29]

Rebellion

With the death of Charles II in 1685 his brother, the Catholic Duke of York, became King James II. On James's succession Churchill was appointed governor of the Hudson's Bay Company. He had also been affirmed Gentleman of the Bedchamber in April, and admitted to the English peerage as Baron Churchill of Sandridge in the county of Hertfordshire in May, thus giving him a seat in the House of Lords. However, the new Parliament was overshadowed by rebellion, led in Scotland by the Earl of Argyll, and in England by Charles II's illegitimate son, the Duke of Monmouth, who, encouraged by malcontents and various Whig conspirators (exiled for their part in the failed Rye House plot), prepared to take what he considered rightfully his – the crown of England.[30]

To face Monmouth's rebels Churchill was given command of the regular foot in the King's army, but the honour of leading the campaign passed to the limited, yet highly loyal, Earl of Feversham. Monmouth had landed at Lyme Regis on 11 June (O.S), but his ill-timed, ill-equipped, and ill-advised peasant rebellion eventually floundered on the Somerset field of Sedgemoor on 6 July 1685 (O.S). Although Churchill's role was subordinate to Feversham, his administrative organisation, tactical skill, and courage in battle were pivotal in the victory. "Sedgemoor may not have been John Churchill's most spectacular victory," writes historian John Tincey, "but it must rightly be considered to be his first".[31]

Churchill had been promoted to Major General on 3 July (O.S), but it was Feversham who received the lion's share of the reward. Churchill was not entirely forgotten, and in August he was awarded the lucrative colonelcy of the Third Troop of Life Guards.[32] Yet according to Historian David Chandler it may be possible that the Sedgemoor campaign, and its subsequent persecutions driven by the bloodthirsty zeal of Judge Jeffreys, set in train a process of disillusion that culminated in his abandonment of his king, and long-time patron and friend, just three years later.[33] His master, however, had already given him cause for anxiety. "If the King should attempt to change our religion," he is reputed to have remarked to Lord Galway shortly after James II's succession, "I will instantly quit his service."[34]

Revolution

Churchill emerged from the Sedgemoor campaign with great credit, but he was anxious not to be seen as sympathetic towards the King's growing religious ardour against the Protestant establishment.[35] James II's promotion of Catholics in royal institutions – including the army – engendered first suspicion, and ultimately sedition in his mainly Protestant subjects; even members of his own family expressed alarm at the King's fanatic zeal for the Roman Catholic religion.[36] When the queen gave birth to a son, James Francis Edward Stuart, it opened up the prospect of a line of successive Catholic monarchs. Some in the King's service, such as the Earl of Salisbury and the Earl of Melfort, betrayed their Protestant upbringing in order to gain favour at court, but although Churchill remained true to his conscience, telling the King, "I have been bred a Protestant, and intend to live and die in that communion", he was also motivated by self-interest. Believing that the monarch's policy would either wreck his own career or generate a wider insurrection, he did not intend, like his unfortunate father before him, to be on the losing side.[37]

Seven men met to draft the invitation to the Protestant Dutch Stadtholder, William, Prince of Orange, to invade England and assume the throne. The signatories to the letter included Whigs, Tories, and the Bishop of London, Henry Compton, who assured the Prince that, "Nineteen parts of twenty of the people ... are desirous of change."[38] William needed no further encouragement. Although the invitation was not signed by Churchill (he was not, as yet, of sufficient political rank to be a signatory), he declared his intention through William's principal English contact in The Hague – "If you think there is anything else that I ought to do, you have but to command me."[39] Churchill, like many others, was looking for an opportune time to desert James.

William landed at Torbay on 5 November 1688 (O.S); from there, he moved his army to Exeter. James II's forces – once again commanded by Lord Feversham – moved to Salisbury, but few of its senior officers were eager to fight – even Princess Anne wrote to William to wish him "good success in this so just an undertaking."[40] Promoted to Lieutenant-General on 7 November (O.S) Churchill was still at his King's side, but displaying "the greatest transports of joy imaginable" at the desertion of Lord Cornbury led Feversham to call for his arrest. Churchill himself had openly encouraged defection to the Orangist cause, but James continued to hesitate.[41] Soon it was too late to act. After the meeting of the council of war on the morning of 24 November (O.S), Churchill, accompanied by some 400 officers and men, slipped from the royal camp and rode towards William in Axminster, leaving behind him a letter of apology and self-justification:

... I hope the great advantage I enjoy under Your Majesty, which I own I would never expect in any other change of government, may reasonably convince Your Majesty and the world that I am actuated by a higher principle ..[42]

When the King saw he could not even keep Churchill – for so long his loyal and intimate servant – he despaired. James II, who in the words of the Archbishop of Rheims, had "given up three kingdoms for a Mass", fled to France, taking with him his son and heir.[43] With barely a shot fired, William had secured the throne, reigning as joint sovereign with his wife Mary, James II's eldest daughter.

William's general

.jpg)

As part of William and Mary's coronation honours, Churchill was created Earl of Marlborough on 9 April 1689 (O.S); he was also sworn to the Privy Council, and made a Gentleman of the King's Bedchamber. His elevation, however, led to accusatory rumours from James II's supporters that Marlborough had disgracefully betrayed his erstwhile king for personal gain; William himself entertained reservations about the man who had deserted James.[44] Marlborough's apologists though, including his most notable descendant and biographer Winston Churchill, have been at pains to attribute patriotic, religious, and moral motives to his action; but in the words of Chandler, it is difficult to absolve Marlborough of ruthlessness, ingratitude, intrigue and treachery against a man to whom he owed virtually everything in his life and career to date.[45]

Marlborough's first official act was to assist in the remodelling of the army – the power of confirming or purging officers and men gave the Earl the opportunity to build a new patronage network which would prove beneficial over the next two decades.[46] His task was urgent, for less than six months after James II's departure, England joined the war against France as part of a powerful coalition aimed at curtailing the ambitions of Louis XIV. With his experience it was logical that Marlborough took charge of the 8,000 British troops sent to the Low Countries in the spring of 1689; yet throughout the Nine Years' War (1688–97) he saw only three years service in the field, and then mostly in subordinate commands. However, at the Battle of Walcourt on 25 August 1689 Marlborough won praise from the Allied commander, Prince Waldeck – " ... despite his youth he displayed greater military capacity than do most generals after a long series of wars ... He is assuredly one of the most gallant men I know."[47] In recognition of his skill and valour William awarded him the lucrative colonelcy of the 7th Foot (later the Royal Fusiliers).

Since Walcourt, though, Marlborough's popularity at court had waned.[48] William and Mary distrusted both Lord and Lady Marlborough's influence as confidants and supporters of Princess Anne (whose claim to the throne was stronger than William's). Sarah had supported Anne in a series of court disputes with the joint monarchs, infuriating Mary who included the Earl in her disfavour of his scheming wife.[49] Yet for the moment the clash of tempers were over-shadowed by more pressing events in Ireland where James had landed in March 1689 in an attempt to regain his thrones. When William left for Ireland in June 1690 Marlborough became commander of all troops and militia in England, and was appointed a member of the Council of Nine to advise Mary on military matters in the King's absence; but she made scant effort to disguise her distaste at his appointment – "I can neither trust or esteem him," she wrote to William.[48]

William III's victory at the Battle of the Boyne on 1 July 1690 (O.S) forced James II to abandon his army and flee back to France. In August Marlborough himself left for Ireland engaged upon his first independent command – a land/sea operation upon southern ports of Cork and Kinsale. It was a bold, imaginative project aimed at disrupting Jacobite supply routes, and one which the Earl conceived and executed with outstanding success.[50] Cork fell on 27 September (O.S), and Kinsale followed in mid-October. Although the campaign did not end the war in Ireland as Marlborough hoped, it taught him the significance of the minutiae of logistics, and the importance of cooperation and tact when working alongside other senior Allied commanders. It would, however, be more than ten years before he once again took charge in the field.[51]

Dismissal and disgrace

William III recognised Marlborough's qualities as a soldier and strategist, but the refusal of the Order of the Garter and failure to appoint him Master-General of the Ordnance, rankled with the ambitious Earl; nor did Marlborough conceal his bitter disappointment behind his usual bland discretion.[52] Using his influence in Parliament and the army, Marlborough aroused dissatisfaction concerning William's preferences for foreign commanders, an exercise designed to force the King's hand.[53] Aware of this, William in turn began to speak openly of his distrust of Marlborough; the Elector of Brandenburg's envoy to London overheard the King remark that he had been treated – "so infamously by Marlborough that, had he not been king, he would have felt it necessary to challenge him to a duel."[54]

Since January 1691 Marlborough had been in contact with the exiled James II in Saint-Germain, anxious to obtain the erstwhile King's pardon for deserting him in 1688 – a pardon essential for the success of his future career in the not altogether unlikely event of a Jacobite restoration.[55] James himself maintained contact with his supporters in England whose principal object was to re-establish him upon his throne. William was well aware of these contacts (as well as others such as Godolphin and the Duke of Shrewsbury), but their double-dealing was seen more in the nature of an insurance policy, rather than as an explicit commitment.[56] Marlborough did not wish for a Jacobite restoration, but William was conscious of his military and political qualities, and the danger the Earl posed: "William was not prone to fear," wrote Thomas Macaulay, "but if there was anyone on earth that he feared, it was Marlborough."[57]

.jpg)

By the time William and Marlborough had returned from an uneventful campaign in the Spanish Netherlands in October 1691, their relationship had further deteriorated. In January 1692, the Queen, angered by Marlborough's intrigues in Parliament, the army, and even with Saint-Germain, ordered Anne to dismiss Sarah from her household – Anne refused. This personal dispute (petty-minded on both sides), precipitated Marlborough's dismissal.[58] On 20 January (O.S), the Earl of Nottingham, Secretary of State, ordered Marlborough to dispose of all his posts and offices, both civil and military, and consider himself dismissed from all appointments and forbidden the court. No reasons were given but Marlborough's chief associates were outraged: Shrewsbury voiced his disapproval and Godolphin threatened to retire from government. Admiral Russell, now commander-in-chief of the Navy, personally accused the King of ingratitude to the man who had "set the crown upon his head."[59]

High treason

The nadir of Marlborough's fortunes had not yet been reached. The spring of 1692 brought renewed threats of a French invasion and new accusations of Jacobite treachery. Acting on the testimony of one Robert Young, the Queen had arrested all the signatories to a letter purporting the restoration of James II and the seizure of William III. Marlborough, as one of these signatories, was sent to the Tower of London on 4 May (O.S) where he languished for five weeks; his anguish compounded by the news of the death of his younger son Charles on 22 May (O.S). Young's letters were eventually discredited as forgeries and Marlborough was released on 15 June (O.S), but he continued his correspondence with James, leading to the celebrated incident of the "Camaret Bay letter" of 1694.[60]

For several months the Allies had been planning an attack upon Brest, the French port in the Bay of Biscay. The French had received intelligence alerting them to the imminent assault, enabling Marshal Vauban to strengthen its defences and reinforce the garrison. Inevitably the attack on 18 June led by Thomas Tollemache ended in disaster; most of his men were killed or captured, and Tollemache himself died of his wounds shortly afterwards. Despite lacking evidence, Marlborough's detractors claimed that it was he who had alerted the enemy. Macaulay states that in a letter on 3 May 1694 Marlborough betrayed the Allied plans to James, thus ensuring that the landing failed and that Tollemache, a talented rival, was killed or discredited as a direct result. Historians such as John Paget and C. T. Atkinson conclude that he probably did write the letter, but did so only when he knew that it would be received too late for its information to be of any practical use (the plan of the attack on Brest was widely known, and the French had already begun to strengthen their defences in April). To Richard Holmes the evidence linking Marlborough with the Camaret Bay letter (which no longer exists), is slender, concluding, "It is very hard to imagine a man as careful as Marlborough, only recently freed from suspicion of treason, writing a letter which would kill him if it fell into the wrong hands."[61] However, David Chandler surmises that, "the whole episode is so obscure and inconclusive that it is still not possible to make a definite ruling. In sum, perhaps we should award Marlborough the benefit of the doubt."[62]

Reconciliation

Mary's death on 28 December 1694 (O.S) eventually led to a formal but cool reconciliation between William III and Anne, now heir to the throne. Marlborough hoped that the rapprochement would lead to his own return to office, but although he and Lady Marlborough were allowed to return to court, the Earl received no offer of employment.[62]

In 1696 Marlborough, together with Godolphin, Russell and Shrewsbury, was yet again implicated in a treasonous plot with James II, this time instigated by the Jacobite militant John Fenwick. The accusations were eventually dismissed as a fabrication and Fenwick executed – the King himself had remained incredulous – but it was not until 1698, a year after the Treaty of Ryswick brought an end to the Nine Years' War, that the corner was finally turned in William's and Marlborough's relationship.[62] On the recommendation of Lord Sunderland (whose wife was a close friend of Lady Marlborough), William eventually offered Marlborough the post of governor to the Duke of Gloucester, Anne's eldest son; he was also restored to the Privy Council, together with his military rank.[63] When William left for Holland in July Marlborough was one of the Lords Justices left running the country in his absence; but striving to reconcile his close Tory connections with that of the dutiful royal servant was difficult, leading Marlborough to complain – "The King's coldness to me still continues."[64]

Later life (1700–22)

War of the Spanish Succession

With the death of the infirm and childless King Charles II of Spain on 1 November 1700, the succession of the Spanish throne, and subsequent control over her empire, once again embroiled Europe in war – the War of the Spanish Succession. On his deathbed Charles II had bequeathed his domains to Louis XIV's grandson, Philip, Duc d'Anjou. This threatened to unite the Spanish and French kingdoms under the House of Bourbon – something unacceptable to England, the Dutch Republic and the Holy Roman Emperor, Leopold I, who had himself a claim to the Spanish throne. With William's health deteriorating (himself estimating he had but a short time to live), and with the Earl's undoubted influence over his successor Princess Anne, the King decided that Marlborough should take centre stage in European affairs. Representing William III in The Hague as Ambassador-Extraordinary and as commander of English forces, Marlborough was tasked to negotiate a new coalition to oppose France and Spain.[65]

On 7 September 1701, the Treaty of the Second Grand Alliance was duly signed by England, the Emperor, and the Dutch Republic to thwart the ambitions of Louis XIV and stem Bourbon power.[66] However, William was not to see England's declaration of war. On 8 March 1702 (O.S) the King, already in a poor state of health, died from injuries sustained in a riding accident, leaving his sister-in-law, Anne, to be immediately proclaimed as his successor. Although the King's death occasioned instant disarray amongst the coalition, Count Wratislaw was able to report that – "The greatest consolation in this confusion is that Marlborough is fully informed of the whole position and by reason of his credit with the Queen can do everything."[67] This 'credit with the Queen' also proved personally profitable to her long-standing friends. Anxious to reward Marlborough for his diplomatic and martial skills in Ireland and on the Continent, Anne made him the Master-General of the Ordnance – an office he had long desired – a Knight of the Garter and Captain-General of her armies at home and abroad. With Lady Marlborough's advancements as Groom of the Stole, Mistress of the Robes, and Keeper of the Privy Purse, the Marlboroughs, now at the height of their powers with the Queen, enjoyed a joint annual income of over £60,000, and unrivalled influence at court.[68]

Early campaigns

On 4 May 1702 (O.S) England formally declared war on France. Marlborough was given command of the English, Dutch, and hired German forces, but he had not as yet commanded a large army in the field, and had far less experience than a dozen Dutch and German generals who must now work under him. His command had its limitations, however. As commander of Anglo-Dutch forces he had the power to give orders to Dutch generals only when their troops were in action with his own; at all other times he had to rely on his powers of tact and persuasion, and gain the consent of accompanying Dutch field deputies or political representatives of the States-General.[69] Nevertheless, despite his Allies' initial lassitude the campaign in the Low Countries (the war's principal theatre) began well for the Duke. After out-manoeuvring Marshal Boufflers, he captured Venlo, Roermond, Stevensweert and Liège, for which in December a grateful Queen publicly proclaimed Marlborough a duke.[70]

On 9 February 1703 (O.S), soon after the Marlboroughs' elevation, their daughter Elizabeth married Scroop Egerton, Earl of Bridgewater. This was followed in the summer by an engagement between Mary and John Montagu, heir to the Earl of, and later Duke of, Montagu, (they later married on 20 March 1705 (O.S)). Their two older daughters were already married: Henrietta to Godolphin's son Francis in April 1698, and Anne to the hot-headed and intemperate Charles Spencer, Earl of Sunderland in 1700.[71] However, Marlborough's hopes of founding a great dynasty of his own reposed in his eldest and only surviving son, John, who, since his father's elevation, had borne the courtesy title of Marquess of Blandford. But while studying at Cambridge in early 1703, the 17-year-old was stricken with a severe strain of smallpox. His parents rushed to be by his side, but on Saturday morning, 20 February (O.S), the boy died, plunging the duke into 'the greatest sorrow in the world'.[72]

Bearing his grief, and leaving Sarah to hers, the Duke returned to The Hague at the beginning of March. By now Marshal Villeroi had replaced Boufflers as commander in the Spanish Netherlands, but although Marlborough was able to take Bonn, Huy, and Limbourg in 1703, continuing Dutch hesitancy prevented him from bringing the French to a decisive battle.[73] Domestically the Duke also encountered resistance. The moderate Tory ministry of Marlborough, the Lord Treasurer Godolphin, and the Speaker of the House of Commons Robert Harley, were hampered by, and often at variance with, their High Tory colleagues whose strategic policy favoured the full employment of the Royal Navy in pursuit of trade advantages and colonial expansion overseas.[74] To the Tories an action at sea was preferable to one ashore; taking a coastal town was preferable to taking one inland. In contrast the Whigs, led by their 'Junto', enthusiastically supported the Ministry's Continental strategy of thrusting the army into the heart of France. This support wilted somewhat following the Allies' recent campaign, but the Duke, whose diplomatic tact had held together a very discordant Grand Alliance, was now a general of international repute, and the limited success of 1703 was soon eclipsed by the Blenheim campaign.[75]

Blenheim and Ramillies

Pressed by the French and Bavarians to the west and Hungarian rebels to the east, Austria faced the real possibility of being forced out of the war.[77] Concerns over Vienna and the situation in southern Germany convinced Marlborough of the necessity of sending aid to the Danube; but the scheme of seizing the initiative from the enemy was extremely bold. From the start the Duke resolved to mislead the Dutch, who would never willingly permit any major weakening of Allied forces in the Spanish Netherlands. To this end, Marlborough moved his English troops to the Moselle (a plan approved of by The Hague), but once there he planned to slip the Dutch leash and march south to link up with Austrian forces in southern Germany.[77]

A combination of strategic deception and brilliant administration enabled Marlborough to achieve his purpose.[78] After marching 250 miles (400 km) from the Low Countries, the Allies fought a series of engagements against the Franco-Bavarian forces ranged against them on the Danube. The first major encounter occurred on 2 July 1704 when Marlborough and Prince Louis of Baden stormed the Schellenberg heights at Donauwörth. However, the main event followed on 13 August when Marlborough – assisted by the Imperial commander, the able Prince Eugene of Savoy – delivered a crushing defeat on Marshal Tallard's and the Elector of Bavaria's army at the Battle of Blenheim. The whole campaign, which historian John Lynn describes as one of the greatest examples of marching and fighting before Napoleon, had been a model of planning, logistics, tactical and operational skill, the successful outcome of which had altered the course of the conflict – Bavaria was knocked out of the war, and Louis XIV's hopes of an early victory were destroyed.[79] With the subsequent fall of Landau on the Rhine, and Trier and Trarbach on the Moselle, Marlborough now stood as the foremost soldier of the age. Even the Tories, who had declared that should he fail they would "break him up like hounds on a hare", could not entirely restrain their patriotic admiration.[80]

.jpg)

The Queen lavished upon her favourite the royal manor of Woodstock and the promise of a fine palace commemorative of his great victory at Blenheim; but since her accession her relationship with Sarah had become progressively distant.[81] The Duke and Duchess had risen to greatness not least because of their intimacy with Anne, but the Duchesses' relentless campaign against the Tories (Sarah was a firm Whig), isolated her from the Queen whose natural inclinations lay with the Tories, the staunch supporters of the Church of England. For her part, Anne, now Queen and no longer the timid adolescent so easily dominated by her more beautiful friend, had grown tired of Sarah's tactless political hectoring and increasingly haughty manner which, in the coming years, were to destroy their friendship and undermine the position of her husband.[82]

During the Duke's march to the Danube Emperor Leopold I offered to make Marlborough a prince of the Holy Roman Empire in the small principality of Mindelheim.[83] The Queen enthusiastically agreed to this elevation, but after the successes of 1704, the campaign of 1705 brought little reason for satisfaction on the Continent. The planned invasion of France via the Moselle valley was frustrated by friend and foe alike, forcing the Duke to withdraw back towards the Low Countries. Although Marlborough penetrated the Lines of Brabant at Elixheim in July, Allied indecision and considerable Dutch hesitancy (concerned as they were for the security of their homeland), prevented the Duke from pressing his advantage.[84] The French and the Tories in England dismissed arguments that only Dutch obstructionism had robbed Marlborough of a great victory in 1705, confirmed in their belief that Blenheim had been a lucky strike and that Marlborough was a general not to be feared.[85]

The early months of 1706 also proved frustrating for the Duke as Louis XIV's generals gained early successes in Italy and Alsace. These setbacks thwarted Marlborough's original plans for the coming campaign, but he soon adjusted his schemes and marched into enemy territory. Louis XIV, equally determined to fight and avenge Blenheim, goaded his commander, Marshal Villeroi, to seek out Monsieur Marlbrouck.[86] The subsequent Battle of Ramillies, fought in the Spanish Netherlands on 23 May, was perhaps Marlborough's most successful action, and one in which he had himself characteristically drawn his sword at the pivotal moment. For the loss of less than 3,000 dead and wounded (far fewer than Blenheim), his victory had cost the enemy some 20,000 casualties, inflicting in the words of Marshal Villars, "the most shameful, humiliating and disastrous of routs". The campaign was an unsurpassed operational triumph for the English general.[87] Town after town subsequently fell to the Allies. 'It really looks more like a dream than truth', wrote Marlborough to Sarah.[88] With Prince Eugene's rout of the French army at Turin in September, 1706 proved a miraculous year for Allied arms.

Falling out of favour

While Marlborough fought in the Low Countries a series of personal and party rivalries instigated a general reversal of fortune.[89] The Whigs, who were the main prop of the war, had been laying siege to Godolphin. As a price for supporting the government in the next parliamentary session, the Whigs demanded a share of public office with the appointment of a leading member of their Junto, the Earl of Sunderland (Marlborough's son-in-law), to the post of Secretary of State.[90] The Queen, who loathed Sunderland and the Junto, and who refused to be dominated by any single party, bitterly opposed the move; but Godolphin, increasingly dependent on Whig support, had little room for manoeuvre. With Sarah's tactless, unsubtle backing, Godolphin relentlessly pressed the Queen to submit to Whig demands. In despair, Anne finally relented and Sunderland received the seals of office; but the special relationship between Godolphin, Sarah, and the Queen had taken a severe blow and she began to turn increasingly to a new favourite – Sarah's cousin, Abigail Masham. Anne also became ever more reliant on the advice of Harley, who, convinced that the duumvirate's policy of appeasing the Whig Junto was unnecessary, had set himself up as alternative source of advice to a sympathetic Queen.[91]

Following his victory at Ramillies Marlborough returned to England and the acclamation of Parliament; his titles and estates were made perpetual upon his heirs, male or female, in order that 'the memory of these deeds should never lack one of his name to bear it'.[92] However, the Allied successes were followed in 1707 with a resurgence in French arms in all fronts of the war, and a return to political squabbling and indecision within the Grand Alliance. The Great Northern War also threatened dire consequences. The French had hoped to entice Charles XII, King of Sweden, to attack the Empire regarding grievances over the Polish Succession, but in a pre-campaign visit to the King's headquarters at Altranstädt, Marlborough's diplomacy helped placate Charles and prevent his interference regarding the Spanish Succession. Nevertheless, major setbacks in Spain at Almanza and along the Rhine in Southern Germany, had caused Marlborough great anxiety and made the Dutch even less cooperative, vetoing the Duke's plans for any major action in the Low Countries.[93] Prince Eugene's retreat from Toulon (Marlborough's major goal for 1707), ended any lingering hopes of a war-winning blow that year.[94]

Marlborough returned from these tribulations to a political storm as the Ministry's critics turned to attack the overall conduct of the war. The Duke and Godolphin had initially agreed to explore a 'moderate scheme' with Harley and reconstruct the government, but they were incensed when Harley privately criticised the management of the war in Spain to the Queen, and his associate Henry St John, the Secretary at War, raised the issue in Parliament. Convinced of Harley's caballing, the duumvirs threatened the Queen with resignation unless she dismissed him. Anne fought stubbornly to keep her favourite minister, but when the Duke of Somerset and the Earl of Pembroke refused to act without 'the General nor the Treasurer', Harley resigned: Henry Boyle replaced him as Secretary of State, and his fellow Whig, Robert Walpole, replaced St John as Secretary at War.[95] The struggle had given Marlborough a final lease of power but it was a Whig victory, and he had to a large extent lost his hold on the Queen.[96]

Oudenarde and Malplaquet

The military setbacks of 1707 continued through the opening months of 1708 with the defection of Bruges and Ghent to the French. Marlborough remained despondent about the general situation, but his optimism received a major boost with the arrival in theatre of Prince Eugene, his co-commander at Blenheim. Heartened by the Prince's robust confidence Marlborough set about to regain the strategic initiative. The plan was in principle a repeat of the double invasion of the previous year; this time with the main blow to fall in the Low Countries. After a forced march the Allies crossed the river Scheldt at Oudenarde just as the French army, under Marshal Vendôme and the duc de Burgundy, was crossing farther north with the intent on besieging the place. Marlborough – with renewed self-assurance – moved decisively to engage them.[97] His subsequent victory at the Battle of Oudenarde on 11 July 1708 demoralised the French army in Flanders; his eye for ground, his sense of timing and his keen knowledge of the enemy were again amply demonstrated.[98] Marlborough now wished to march directly on Paris, but counselled by a more cautious Eugene the Allies instead resolved upon the Siege of Lille, the strongest fortress in Europe. While the Duke commanded the covering force, Eugene oversaw the siege of the town which surrendered on 22 October; however, it was not until 10 December that the resolute Boufflers yielded the citadel. Yet for all the difficulties of the winter siege, the campaign of 1708 had been a remarkable success, requiring superior logistical skill and organisation.[99] The Allies re-took Bruges and Ghent, and the French were driven out of almost all the Spanish Netherlands: "He who has not seen this," wrote Eugene, "has seen nothing."[100]

While Marlborough achieved honours on the battlefield, the Whigs, now in the ascendancy, drove the remaining Tories from the Cabinet. Marlborough and Godolphin, now distanced from Anne, would henceforth have to conform to the decisions of a Whig ministry, while the Tories, sullen and vengeful, looked forward to their former leaders' downfall. To compound his troubles the Duchess, spurred on by her hatred of Harley and Abigail, had finally driven the Queen to distraction and wrecked what was left of their friendship. Sarah was retained in her court position out of necessity as the price to be paid to keep her victorious husband at the head of the army.[101]

After the recent defeats and one of the worst winters in modern history, France was on the brink of collapse.[102] However, Allied demands at the peace talks in The Hague in April 1709 (principally concerning Article 37 that bound Louis XIV to hand over Spain within two months or face the renewal of the war), were rejected by the French in June. The Whigs, the Dutch, Marlborough and Eugene failed for personal and political reasons to secure a favourable peace, adhering to the uncompromising slogan 'No peace without Spain' without any clear knowledge of how to accomplish it. All the while Harley, maintained up the backstairs by Abigail, rallied the moderates to his side, ready to play an ambitious and powerful middle part.[103]

Marlborough returned to campaigning in the Low Countries in June 1709. After outwitting Marshal Villars to take the town of Tournai on 3 September (a major and bloody operation), the Allies turned their attention upon Mons, determined to maintain the ceaseless pressure on the French.[104] With direct orders from the increasingly desperate Louis XIV to save the city, Villars advanced on the tiny village of Malplaquet on 9 September 1709 and entrenched his position. Two days later the opposing forces clashed in battle. On the Allied left flank the Prince of Orange led his Dutch infantry in desperate charges only to have it cut to pieces. On the other flank, Eugene attacked and suffered almost as severely. Nevertheless, sustained pressure on his extremities forced Villars to weaken his centre, enabling Marlborough to breakthrough and claim victory. Yet the cost was high: the allied casualty figures were approximately double that of the enemy (sources vary), leading Marlborough to admit – "The French have defended themselves better in this action than in any battle I've seen."[105] The Duke proceeded to take Mons on 20 October, but on his return to England his enemies used the Malplaquet casualty figures to sully his reputation. Harley, now master of the Tory party, did all he could to persuade his colleagues that the pro-war Whigs – and by their apparent concord with Whig policy, Marlborough and Godolphin – were bent on leading the country to ruin.[106]

Endgame

The Allies had confidently expected that victory in a major set-piece battle would compel Louis XIV to accept peace on Allied terms, but after Malplaquet (the bloodiest battle of the war), that strategy had lost its validity: Villars had only to avoid defeat for a compromise peace settlement to become inevitable.[107] In March 1710, fresh peace talks re-opened at Geertruidenberg, but again Louis XIV would not concede Whig demands to force his grandson, Philip V, from Spain. Publicly Marlborough toed the government line, but privately he had real doubts about pressing the French into accepting such a dishonourable course.[108]

Although the Duke was only an observer at Geertruidenberg, the failed negotiations gave credence to his detractors that he was deliberately prolonging the war for his own profit. Yet it was with reluctance that he returned to campaigning in the spring, capturing Douai in June, before taking Béthune, and Saint-Venant, followed in November by Aire-sur-la-Lys. Nevertheless, support for the pro-war policy of the Whigs had, by this time, ebbed away. The Cabinet had long lacked cohesion and mutual trust (particularly following the Sacheverell affair) when in the summer the plan to break it up, prepared by Harley, was brought into action by the Queen.[109] Sunderland was dismissed in June, followed by Godolphin (who had refused to sever his ties with Sarah) in August. Others followed. The result of the general election in October was a Tory landslide and a victory for the peace policy. Marlborough remained at the head of the army, however. The defeated Junto, the Dutch, Eugene and the Emperor, implored him to stand by the common cause, while the new ministers, knowing they had to fight another campaign, required him to maintain the pressure on the enemy until they had made their own arrangements for the peace.[110]

The Duke, 'much thinner and greatly altered', returned to England in November. His relationship with Anne had suffered further setbacks in recent months (she had refused to grant him his requested appointment of Captain-General for life, and had interfered in military appointments).[111] The damage done to Marlborough's general standing was substantial because it was so visible. For now, though, the central issue was the Duchess whose growing resentment of Harley and Abigail had finally persuaded the Queen to be rid of her. Marlborough visited Anne on 17 January 1711 (O.S) in a last attempt to save his wife, but she was not to be swayed, and demanded Sarah give up her Gold Key (the symbol of her office) within two days, warning, "I will talk of no other business till I have the key."[112]

Notwithstanding all this turmoil – and his declining health – Marlborough returned to The Hague in late February to prepare for what was to be his last campaign, and one of his greatest. Once again Marlborough and Villars formed against each other in line of battle, this time along the Avesnes-le-Comte–Arras sector of the lines of Non Plus Ultra (see map). By an exercise of brilliant psychological deception,[113] and a secretive night march covering nearly 40 miles in 18 hours, the Allies penetrated the allegedly impregnable lines without losing a single man; Marlborough was now in position to besiege the fortress of Bouchain.[114] Villars, deceived and outmanoeuvred, was helpless to intervene, compelling the fortress's unconditional surrender on 12 September. Chandler writes – "The pure military artistry with which he repeatedly deceived Villars during the first part of the campaign has few equals in the annals of military history ... the subsequent siege of Bouchain with all its technical complexities, was an equally fine demonstration of martial superiority."[115]

For Marlborough, though, time had run out. His strategic gains in 1711 made it virtually certain that the Allies would march on Paris the following year, but Harley had no intention of letting the war progress that far and risk jeopardizing the favourable terms secured from the secret Anglo-French talks (based on the idea that Philip V would remain on the Spanish throne) that had proceeded throughout the year.[116] Marlborough had long had doubts about the Whig policy of 'No Peace without Spain', but he was reluctant to abandon his allies (including the Elector of Hanover, Anne's heir presumptive), and sided with the Whigs in opposing the peace preliminaries.[117] Personal entreaties from the Queen (who had long tired of the war), failed to persuade the Duke. The Elector made it clear that he too was against the proposals, and publicly sided with the Whigs. Nevertheless, Anne remained resolute, and on 7 December 1711 (O.S) she was able to announce that – "notwithstanding those who delight in the arts of war" – a sneer towards Marlborough – "both time and place are appointed for opening the treaty of a general peace."[118]

Dismissal

To prevent the serious renewal of warfare in the spring it was considered essential to replace Marlborough with a general more in touch with the Queen's ministers and less in touch with their allies. To do this, Harley (newly created Earl of Oxford) and St John, first needed to bring charges of corruption against the Duke, completing the anti-Whig, anti-war picture that Jonathan Swift was already presenting to a credulous public through his pamphleteering, notably in his Conduct of the Allies (1711).[119] The means to achieve Marlborough's fall had already been put in train when the Ministry had set up a Parliamentary 'Commission for the taking, examining and stating the public accounts of the Kingdom', to report on alleged irregularities during the war.

Two main charges were brought to the House of Commons against Marlborough: first, an assertion that over nine years he had illegally received more than £63,000 from the bread and transport contractors in the Netherlands; second, that he had taken 2.5% from the pay of the foreign troops in English pay, amounting to £280,000.[120] Despite Marlborough's refutations (claiming ancient precedent for the first allegation, and, for the second, producing a warrant signed by the Queen in 1702 authorising him to make the deductions in lieu of secret-service money for the war), the findings were enough for Harley to persuade the Queen to release her Captain-General. On 29 December 1711 (O.S), before the charges had been examined, Anne, who owed to him the success and glory of her reign, sent her letter of dismissal: "I am sorry for your own sake the reasons are become so public which makes it necessary for me to let you know you have render'd it impracticable for you to continue yet longer in my service."[121] The Tory dominated Parliament concluded by a substantial majority that, 'the taking of several sums of money annually by the Duke of Marlborough from the contractor for foraging the bread and wagons ... was unwarrantable and illegal', and that the 2.5% deducted from the pay of foreign troops 'is public money and ought to be accounted for.'[122] When his successor, the Duke of Ormonde, left London for The Hague to take command of British forces he went, noted Bishop Burnet, with 'the same allowances that had been lately voted criminal in the Duke of Marlborough'.[123]

The Allies were stunned by Marlborough's dismissal. The French, however, rejoiced at the removal of the main obstacle to the Anglo-French talks. Oxford (Harley) and St John had no intention of letting Britain's new Captain-General undertake any action, and issued Ormonde his 'restraining orders' in May, forbidding him to use British troops in action against the French – an infamous step that ultimately ruined Eugene's campaign in Flanders.[124] Marlborough continued to make his views known, but he was in trouble: attacked by his enemies and the government press; with his fortune in peril and Blenheim Palace still unfinished and running out of money; and with England split between Hanoverian and Jacobite factions, Marlborough thought it wise to leave the country. After attending Godolphin's funeral on 7 October (O.S) he went into voluntary exile to the Continent on 1 December 1712 (O.S).[125]

Return to favour

Marlborough was welcomed and fêted by the people and courts of Europe, where he was not only respected as a great general but also as a prince of the Holy Roman Empire.[126] Sarah joined him in February 1713, and was delighted when on reaching Frankfurt in the middle of May to see that the troops under Eugene's command paid her lord 'all the respects as if he had been at his old post'.[127] The Duke also journeyed to his principality of Mindelheim which was destined, as he suspected, to revert back to Bavaria at the conclusion of the peace negotiations.

Throughout his travels Marlborough remained in close contact with the Electoral court of Hanover, determined to ensure a bloodless Hanoverian succession on Anne's death. He also maintained correspondence with the Jacobites. The spirit of the age saw little wrong in Marlborough's continuing friendship with his nephew, the Duke of Berwick, James II's illegitimate son with Arabella. But these assurances against a Jacobite restoration (which he had been taking out since the early years of William III, no matter how insincere), stirred Hanoverian suspicions, and perhaps prevented him from holding the first place in the counsels of the future George I.[128]

.jpg)

The representatives of France, Great Britain, and the Dutch Republic signed the Treaty of Utrecht on 11 April 1713 (O.S) – the Emperor and his German allies, including the Elector of Hanover, continued with the war before finally accepting the general settlement the following year. The Treaty marked Britain's emergence as a great power. Domestically, however, the country remained divided between Whig and Tory, Jacobite and Hanoverian factions. By now Oxford and St John (Viscount Bolingbroke since 1712) – absorbed entirely by their mutual enmity and political squabbling – had effectively wrecked the Tory administration.[129] Marlborough had been kept well informed of events while in exile and had remained a powerful figure on the political scene, not least because of the personal attachment the Queen still retained for him.[130] After the death of his daughter Elizabeth from smallpox in March 1714, Marlborough contacted the Queen. Although the contents of the letter are unknown it is possible that Anne may have summoned him home. Either way, it seems that an agreement was reached to reinstate the Duke in his former offices.[131]

Oxford's period of predominance was now at an end, and Anne turned to Bolingbroke and Marlborough to assume the reins of government and ensure a smooth succession. But beneath the weight of hostility the Queen's health, already fragile, rapidly deteriorated, and on 1 August 1714 (O.S) – the day the Marlboroughs returned to England – she died.[132] The Privy Council immediately proclaimed the Elector of Hanover King George I of England. The Jacobites had proved incapable of action; what Daniel Defoe called the 'solidity of the constitution' had triumphed, and the regents chosen by George prepared for his arrival.[133] The accession boded ill for the 'men of Utrecht' – Bolingbroke and Oxford. Bolingbroke (a staunch Jacobite) fled to France, while vengeful Whigs pursued Oxford to the Tower. In contrast, Marlborough was received with the greatest cordiality. The new King had not entirely forgiven him his flirtations with Saint-Germain, and he had no intention of employing him in any but military capacities. However, reappointed as Captain-General, Master-General of Ordnance, and Colonel of the 1st Foot Guards, Marlborough once more became a person of influence and respect at court.

The Duke's return to favour under the House of Hanover enabled him to preside over the 1715 Jacobite rising from London (although it was his former assistant, Cadogan, who directed the operations). But his health was fading, and on 28 May 1716 (O.S), shortly after the death of his daughter Anne, Countess of Sunderland, he suffered a paralytic stroke at Holywell House. This was followed by another, more severe stroke in November, this time at a house on the Blenheim estate. The Duke recovered somewhat, but while his speech had become impaired his mind remained clear, recovering enough to ride out to watch the builders at work on Blenheim Palace and attend the Lords to vote for Oxford's impeachment.[134]

In 1719 the Duke and Duchess were able to move into the east wing of the unfinished palace, but Marlborough had only three years to enjoy it. While living at Windsor Lodge he suffered another stroke in June 1722, not long after his 72nd birthday. Finally, at 4 a.m on 16 June (O.S), in the presence of his wife and two surviving daughters Henrietta Godolphin and Mary Montagu, the 1st Duke of Marlborough died. He was initially buried in the vault at the east end of Henry VII's chapel in Westminster Abbey, but following instructions left by Sarah, who died in 1744, Marlborough was moved to be by her side lying in the vault beneath the chapel at Blenheim.[135]

Assessment

To military historians David Chandler and Richard Holmes, Marlborough is the greatest British commander in history, an assessment that is shared by others, including the Duke of Wellington who could "conceive nothing greater than Marlborough at the head of an English army." However, the Whig historian, Thomas Macaulay, denigrates Marlborough throughout the pages of his History of England who, in the words of historian John Wilson Croker, pursues the Duke with "more than the ferocity, and much less than the sagacity, of a bloodhound."[136] Macaulay adopted his unfavourable reading of Marlborough straight from Swift and the Tory pamphleteers of the latter part of Anne's reign. According to George Trevelyan, Macaulay 'instinctively desired to make Marlborough's genius stand out bright against the background of his villainy'.[137] It was in response to Macaulay's History that Winston Churchill wrote his four volume work, Marlborough: His Life and Times.

Marlborough was ruthlessly ambitious, relentless in the pursuit of wealth, power and social advancement, earning him a reputation for avarice and miserliness. These traits may have been exaggerated for the purposes of party faction but, notes Trevelyan, nearly all other statesmen of the day were engaged in founding families and amassing estates at the public expense; Marlborough only differed in that he gave the public much more value for their money.[138] In his quest for fame and personal interests he could be unscrupulous, as his desertion of James II testifies. To Macaulay this is regarded as a piece of selfish treachery against his patron; an analysis shared by G. K. Chesterton: "Churchill, as if to add something ideal to his imitation of Iscariot, went to James with wanton professions of love and loyalty ... and then calmly handed over the army to the invader."[139] To Trevelyan, Marlborough's behaviour during the 1688 revolution was a sign of his 'devotion to the liberties of England and the Protestant religion'.[140] However, his continuing correspondence with Saint-Germain was not noble. Although Marlborough did not wish for a Jacobite restoration his double-dealing ensured that William III and George I would never be fully disposed to trust him.[141]

Marlborough's weakness during Anne's reign lay in the English political scene. His determination to preserve the independence of the Queen's administration from control of party faction initially enjoyed full support, but once royal favour turned elsewhere, the Duke, like his key ally Godolphin, found himself isolated; first becoming little more than a servant of the Whigs, then a victim of the Tories.[142]

Captain-General

On the grand strategic level Marlborough had a rare grasp of the broad issues involved, and was able from the start of the Spanish Succession war to see the conflict in its entirety. He was one of the few influences working towards genuine unity within the Grand Alliance, but the extension of the war aims to include the replacement of Philip V as King of Spain was a fatal mistake.[143] Marlborough stands accused – possibly for political and diplomatic reasons – of not pressing his private doubts about reinforcing failure. Spain proved a continuous drain of men and resources, and ultimately hampered his chances of complete success in Flanders, the war's main theatre.[143] The Allies did come close to a complete victory on several occasions, but the increasingly severe conditions imposed upon Louis XIV forestalled an early end to hostilities. Although the Duke lost his political influence in the latter stages of the war he still possessed vast prestige abroad, yet his failure to communicate his innermost convictions to his allies or political masters means he must bear some responsibility for the continuance of the war beyond its logical conclusion.[143]

As a commander Marlborough preferred battle over slow moving siege warfare. Aided by an expert staff (particularly his carefully selected aides-de-camp such as Cadogan), as well as enjoying a close personal relationship with the talented Imperial commander, Prince Eugene, Marlborough proved far-sighted, often far ahead of his contemporaries in his conceptions, and was a master at assessing his enemy's characteristics in battle.[144] Marlborough was more likely to manoeuvre than his opponents, and was better at maintaining operational tempo at critical times, yet the Duke qualifies more as a great practitioner within the constraints of early 18th century warfare, rather than as a great innovator who radically redefined military theory.[145] Nevertheless, his predilection for fire, movement, and co-ordinated all-arms attacks, lay at the root of his great battlefield successes.[146]

As an administrator Marlborough was also without peer; his attention to detail meant his troops rarely went short of supply – when his army arrived at its destination it was intact and in a fit state to fight.[147] This concern for the welfare of the common soldier together with his ability to inspire trust and confidence, and his willingness to share the dangers of battle, often earned him adulation from his men – "The known world could not produce a man of more humanity," observed Corporal Matthew Bishop.[148] It was this range of abilities that makes Marlborough outstanding.[147] Even his old adversaries recognised the Duke's qualities. In his Letters on the Study of History (1752), Bolingbroke declared – "I take with pleasure this opportunity of doing justice to that great man ... [whose memory] as the greatest general, and as the greatest minister that our country, or perhaps any other has produced, I honour."[149] His success was made possible because of his enormous reserves of stamina, willpower and self-discipline; his ability to hold together the Alliance against France, made possible by his victories, can hardly be overestimated.[150] As direct descendant Winston Churchill declared: "He commanded the armies of Europe against France for ten campaigns. He fought four great battles and many important actions ... He never fought a battle that he did not win, nor besieged a fortress that he did not take ... He quitted war invincible."[151] No other British soldier has ever carried so great a weight and variety of responsibility.[147]

Arms

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

List of deserters from James II to William of Orange

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 All dates in the article are in the Gregorian calendar (unless otherwise stated). The Julian calendar as used in England until 1752 differed by eleven days after 1700, and ten days prior to that date. Thus, the battle of Blenheim was fought on 13 August (Gregorian calendar) or 2 August (Julian calendar). In this article (O.S) is used to annotate Julian dates with the year adjusted to 1 January. See the article Old Style and New Style dates for a more detailed explanation of the dating issues and conventions.

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, 27. Churchill insists that the often recorded fine of £4446 18s was a misprint in Hutchin's History of Dorset, 1774. This huge figure was subsequently, and erroneously repeated by other Marlborough biographers including Coxe.

- ↑ Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 42. Winston, Henry, Jasper, and Mountjoy all died in infancy. Theobald died in 1685

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, 30. Sources vary as to the year Arabella was born: Holmes states 1647, Gregg 1648.

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, 31

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, 60

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 5

- ↑ Coxe: Memoirs of the Duke of Marlborough, I, 2

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, 6

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 5. Although details of this period are sketchy, it is surmised that in 1670 he also served aboard ship in the naval blockade of the Barbary pirate-den of Algiers.

- ↑ Hibbert The Marlboroughs, 7. Churchill was 20, she was 29 when they became lovers.

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, 60.

- ↑ Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 58. Churchill never formally acknowledged his daughter with Cleveland.

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, 40

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs 9. There is, however, no extant record of Churchill's conduct in the Battle of Solebay.

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 7

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 8

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, 13

- ↑ Field: The Favourite: Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, 8

- ↑ Field: The Favourite: Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, 23

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, 129

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Barnett: Marlborough, 43

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 10

- ↑ Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 92. In the meantime Churchill was dispatched on various important diplomatic missions, including to Paris to further negotiations for a subsidy from Louis XIV, which could help Charles II survive without calling another Parliament, and thus reduce the risk of an Exclusion Bill being passed.

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, 164

- ↑ Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 102

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, 28

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, 135

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, 179

- ↑ Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 110

- ↑ Tincey: Sedgemoor 1685: Marlborough's First Victory, 158

- ↑ Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 126

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 22.

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 12–13

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, 36.

- ↑ Coxe: Memoirs of the Duke of Marlborough, I, 18

- ↑ Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 139–40

- ↑ Miller: James II, 187

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, 240

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, 41.

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 24.

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, 263

- ↑ Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 194

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, 46

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 25

- ↑ Jones: Marlborough, 41

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, 48

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 35

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 35. Anne wished to have her own Civil list income granted by Parliament, rather than a grant from the Privy Purse, which meant reliance on William III. In this, and other matters, Sarah supported Anne.

- ↑ Jones: Marlborough, 44

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 44

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, 22

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 46

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, 57

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, 327

- ↑ Churchill: A History of the English-Speaking Peoples: Age of Revolution, 11

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, 341

- ↑ Jones: Marlborough, 47

- ↑ Churchill: A History of the English-Speaking Peoples: Age of Revolution, 12

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 47

- ↑ Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 184

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 48

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, 80. Marlborough's son John, was appointed Master of the Horse at a salary of £500 a year.

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 49

- ↑ Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 192–93

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, 126: Marlborough was also to settle the number of soldiers and sailors each coalition partner was to contribute, and supervise the organisation and supply of these troops. In these matters he was ably assisted by Adam Cardonnel and William Cadogan.

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, 24

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, 153. £4 million in today's money.

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, 31. The Dutch generals and deputies were concerned by the threat of an invasion from a powerful enemy.

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 107. The Queen also granted him £5,000 annually for life, but Parliament refused. Sarah, indignant at this ingratitude, suggested he refuse the title.

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, 118. Marlborough himself was not keen on the marriage but Sarah, enchanted by Sunderland's Whig ideology and intellectual prowess, was decidedly more enthusiastic.

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, 115

- ↑ Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 247

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, 133

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 122

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, 121

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714, 286

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 128

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714, 294

- ↑ Churchill: A History of the English-Speaking Peoples: Age of Revolution, 44

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, 192

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, 181

- ↑ The Bavarian estate had been confiscated from the Elector and effectively occupied after Blenheim.

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 164

- ↑ Jones: Marlborough, 109–10

- ↑ Chandler: A Guide to the Battlefields of Europe, 28

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714, 308

- ↑ Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 349

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 2, 193

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 2, 196

- ↑ Barnet: Marlborough, 195

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times Bk. 2, 214

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 195

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 199

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 2, 313

- ↑ Churchill: A History of the English-Speaking Peoples: Age of Revolution, 58

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714, 319

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 222

- ↑ Jones: Marlborough, 170–71

- ↑ McKay: Prince Eugene of Savoy, 117

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, 278

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, 279

- ↑ Churchill: A History of the English-Speaking Peoples: Age of Revolution, 64

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 251

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 266

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, 229

- ↑ Jones: Marlborough, 185

- ↑ Jones: Marlborough, 215

- ↑ Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne, III, 40

- ↑ Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne, III, 69

- ↑ Against Marlborough's wishes, and prompted by Harley, the Queen appointed Lord Rivers for the post of Constable of the Tower, and awarded the colonelcy of the Oxford Dragoons to Jack Hill, brother of Abigail Masham.

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, 268. Abigail Masham and the Duchess of Somerset divided between them Sarah's places at court, and in bitterness she retired to her newly built mansion of Marlborough House.

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, 259

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714, 343

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 299

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, 339

- ↑ Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 459

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, 347

- ↑ Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne, III, 198

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 302

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, 349. Marlborough threw the letter on the fire in disgust, but Oxford's memoranda contains an imperfect draft copy.

- ↑ Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 463

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, 356

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 304

- ↑ Jones: Marlborough, 222

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, 290

- ↑ Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 465

- ↑ Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne, III, 272

- ↑ Jones: Marlborough, 224

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, 389