American Jews

|

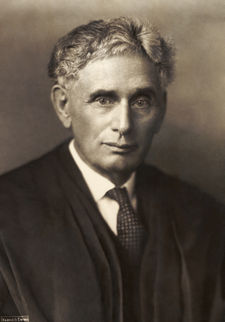

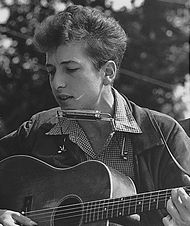

| Isaac Asimov • Louis Brandeis • Bob Dylan Albert Einstein • Dianne Feinstein • Betty Friedan Milton Friedman • Allen Ginsberg • Hank Greenberg Henry Kissinger • Steven Spielberg • Barbra Streisand |

| Total population |

|---|

| 6,489,000 approx. (2008) 1.7–2.2% of the U.S. population[1] up from 6,141,325 in 2000[2] |

| Regions with significant populations |

| New York metropolitan area, Greater Boston, all along the Northeast Megalopolis in the Northeastern United States, South Florida, Washington DC area, the West Coast (especially the Los Angeles and San Francisco areas), the Chicago–Milwaukee corridor |

| Languages |

|

Traditional Jewish languages |

| Religion |

| Related ethnic groups |

|

Ashkenazi Jews, Mizrahi Jews, Sephardi Jews, other Jewish ethnic divisions |

American Jews, also known as Jewish Americans, are American citizens or resident aliens of the Jewish faith and/or Jewish ethnicity. The Jewish community in the United States is composed predominantly of Ashkenazi Jews who emigrated from Central and Eastern Europe, and their U.S.-born descendants. A minority from all Jewish ethnic divisions are also represented, including Sephardi Jews, Mizrahi Jews, and a number of converts. The American Jewish community manifests a wide range of Jewish cultural traditions, as well as encompassing the full spectrum of Jewish religious observance.

Depending on religious definitions and varying population data, the United States is home to the largest or second largest (after Israel) Jewish community in the world. The population of American adherents of Judaism was estimated to be approximately 5,128,000 (1.7%)[3] of the total population in 2007 (301,621,000)[4]; including those who identify themselves culturally as Jewish (but not necessarily religiously), this population was estimated at 6,489,000 (2.2%) as of 2008.[5] As a contrast, Israel's Central Bureau of Statistics estimated the Israeli Jewish population was 5,664,000 in 2009 (75.4% of the total population).[6]

Contents |

History

Jews have been present in what is today the United States of America as early as the 17th century.[7] [8] However, they were small in numbers and almost exclusively Sephardic Jewish immigrants of Spanish and Portuguese ancestry.[9] While denied the vote or ability to hold office in some areas, Sephardic Jews became active in community affairs in the 1790s, after achieving political equality in the five states where they were most numerous.[10] Until about 1830, Charleston, South Carolina had more Jews than anywhere else in North America. Large scale Jewish immigration, however, did not commence until the nineteenth century, when, by mid-century, many secular Ashkenazi Jews from Germany arrived in the United States, primarily becoming merchants and shop-owners. There were approximately 250,000 Jews in the United States by 1880, many of them being the educated, and largely secular, German Jews, although a minority population of the older Sephardic Jewish families remained influential.

Jewish immigration to the United States increased dramatically in the early 1880s, as a result of persecution in parts of Eastern Europe. Most of these new immigrants also were Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews, though most came from the poor rural populations of the Russian Empire and the Pale of Settlement, located in modern-day Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova. Over 2,000,000 Jews arrived between the late nineteenth century and 1924, when the Immigration Act of 1924 and the National Origins Quota of 1924 restricted immigration. Most settled in the New York metropolitan area, establishing what became one of the world's major concentrations of Jewish population.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, these newly arrived Jews built support networks consisting of many small synagogues and Ashkenazi Jewish Landsmannschaften (German for "Territorial Associations") for Jews from the same town or village. American Jewish writers of the time urged assimilation and integration into the wider American culture, and Jews quickly became part of American life. 500,000 American Jews (or half of all Jewish males between 18 and 50) fought in World War II, and after the war younger families joined the new trend of suburbanization. There, Jews became increasingly assimilated and demonstrated rising intermarriage. The suburbs facilitated the formation of new centers, as Jewish school enrollment more than doubled between the end of World War II and the mid-1950s, while synagogue affiliation jumped from 20% in 1930 to 60% in 1960; the fastest growth came in Reform and, especially, Conservative congregations.[11] More recent waves of Jewish immigration from Russia and other regions have largely joined the mainstream American Jewish community.

Self identity

Korelitz (1996) shows how American Jews during the late 19th and early 20th centuries abandoned a racial definition of Jewishness in favor of one that embraced ethnicity. The key to understanding this transition from a racial self-definition to a cultural or ethnic one can be found in the ‘’Menorah Journal’’ between 1915 and 1925. During this time contributors to the Menorah promoted a cultural, rather than a racial, religious, or other view of Jewishness as a means to define Jews in a world that threatened to overwhelm and absorb Jewish uniqueness. The journal represented the ideals of the menorah movement established by Horace M. Kallen and others to promote a revival in Jewish cultural identity and combat the idea of race as a means to define or identify peoples.[12]

Siporin (1990) uses the family folklore of ethnic Jews to their collective history and its transformation into an historical art form. They tell us how Jews have survived being uprooted and transformed. Many immigrant narratives bear a theme of the arbitrary nature of fate and the reduced state of immigrants in a new culture. By contrast, ethnic family narratives tend to show the ethnic more in charge of his life, and perhaps in danger of losing his Jewishness altogether. Some stories show how a family member successfully negotiated the conflict between ethnic and American identities.[13]

After 1960 memories of the Holocaust, together with the Six Day War in 1967 that resulted in the survival of Israel had major impacts on fashioning Jewish ethnic identity. The Shoah provided Jews with a rationale for their ethnic distinction at a time when other minorities were asserting their own.[14]

Politics

| Election year | Democrat candidate | % of Jewish vote | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | Franklin D. Roosevelt | 90 | Won |

| 1944 | Franklin D. Roosevelt | 90 | Won |

| 1948 | Harry Truman | 75 | Won |

| 1952 | Adlai Stevenson | 64 | Lost |

| 1956 | Adlai Stevenson | 60 | Lost |

| 1960 | John F. Kennedy | 82 | Won |

| 1964 | Lyndon B. Johnson | 90 | Won |

| 1968 | Hubert Humphrey | 81 | Lost |

| 1972 | George McGovern | 65 | Lost |

| 1976 | Jimmy Carter | 71 | Won |

| 1980 | Jimmy Carter | 45 | Lost |

| 1984 | Walter Mondale | 67 | Lost |

| 1988 | Michael Dukakis | 64 | Lost |

| 1992 | Bill Clinton | 80 | Won |

| 1996 | Bill Clinton | 78 | Won |

| 2000 | Al Gore | 79 | Lost |

| 2004 | John Kerry | 76 | Lost |

| 2008 | Barack Obama | 78 | Won |

|- } [15] In New York City, while the German Jewish community was well established 'uptown', the more numerous East European Jews faced tension 'downtown' with Irish and German Catholic neighbors, especially the Irish Catholics who controlled Democratic Party Politics[16] at the time. Jews successfully established themselves in the garment trades and in the needle unions in New York. By the 1930s they were a major political factor in New York, with strong support for the most liberal or socialist programs of the New Deal. They continued as a major element of the New Deal Coalition, giving special support to the Civil Rights Movement. By the mid 1960s, however, the Black Power movement caused a growing separation between blacks and Jews, though both groups remained solidly in the Democratic camp.[17]

While earlier Jewish immigrants from Germany tended to be politically conservative, the wave of Eastern European Jews starting in the early 1880s, were generally more liberal or left wing and became the political majority.[18] Many came to America with experience in the socialist, anarchist and communist movements as well as the Labor Bund, emanating from Eastern Europe. Many Jews rose to leadership positions in the early 20th century American labor movement and helped to found unions that played a major role in left wing politics and, after 1936, in Democratic Party politics.[18]

Although American Jews generally leaned Republican in the second half of the 19th century, the majority has voted Democratic or leftist since at least 1916, when they voted 55% for Woodrow Wilson.[19] American Jews voted 90% for Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt in the elections of 1940, and 1944, representing the highest of support, only equaled once since. In the election of 1948, Jewish support for Democrat Harry S. Truman dropped to 75%, with 15% supporting the new Progressive Party.[19] As a result of lobbying, and hoping to better compete for the Jewish vote, both major party platforms had included a pro-Zionist plank since 1944, and supported the creation of a Jewish state;[20] it had little apparent effect however, with 90% still voting other-than Republican. In every election since, no Democratic presidential candidate has won with less than 71% of the Jewish vote.

During the 1952 and 1956 elections, they voted 60% or more for Democrat Adlai Stevenson, while General Eisenhower garnered 40% for his reelection; the best showing to date for the Republicans since Harding's 43% in 1920.[19] In 1960, 83% voted for Democrat John F. Kennedy against Richard Nixon, and in 1964, 90% of American Jews voted for Lyndon Johnson, over his Republican opponent, arch-conservative Barry Goldwater. Hubert Humphrey garnered 81% of the Jewish vote in the 1968 elections, in his losing bid for president against Richard Nixon.[19]

During the Nixon re-election campaign of 1972, Jewish voters were apprehensive about George McGovern and only favored the Democrat by 65%, while Nixon more than doubled Republican Jewish support to 35%. In the election of 1976, Jewish voters supported Democrat Jimmy Carter by 71% over incumbent president Gerald Ford’s 27%, but during the Carter re-election campaign of 1980, Jewish voters greatly abandoned the Democrat, with only 45% support, while Republican winner, Ronald Reagan, garnered 39%, and 14% went to independent John Anderson.[19][21]

During the Reagan re-election campaign of 1984, the Republican retained 31% of the Jewish vote, while 67% voted for Democrat Walter Mondale. The 1988 election saw Jewish voters favor Democrat Michael Dukakis by 64%, while George Bush Sr. polled a respectable 35%, but during his re-election in 1992, Jewish support dropped to just 11%, with 80%, voting for Bill Clinton and 9% going to independent Ross Perot. Clinton’s re-election campaign in 1996 maintained high Jewish support at 78%, with 16% supporting Robert Dole and 3% for Perot.[19][21]

The elections of 2000 and 2004 saw continued Jewish support for Democrats Al Gore and John Kerry, a Catholic, remain in the high- to mid-70% range, while Republican George W. Bush’s re-election in 2004 saw Jewish support rise from 19% to 24%.[21][22]

In the 2008 presidential election, 78% of Jews voted for Barack Obama, who became the first African-American to be elected president.[23] Additionally, 83% of white Jews voted for Obama compared to just 34% of white Protestants and 47% of white Catholics, though 67% of those identifying with another religion and 71% identifying with no religion also voted Obama.[24]

For congressional and senate races, since 1968, American Jews have voted about 70–80% for Democrats; this support increased to 87% for Democratic House candidates during the 2006 elections.[25] Currently there are 14 Jews among 100 U.S. Senators: 12 Democrats (Michael Bennet, Barbara Boxer, Benjamin Cardin, Russ Feingold, Dianne Feinstein, Al Franken, Herb Kohl, Frank Lautenberg, Carl Levin, Charles Schumer, Arlen Specter, Ron Wyden), and both of the Senate's independents (Joe Lieberman and Bernie Sanders; both caucus with the Democrats). Two states have two Jewish Senators: Wisconsin (Kohl and Feingold) and California (Feinstein and Boxer).[26]

There are 30 Jews among the 435 U.S. Representatives;[27] 29 are Democrats and one (Eric Cantor) is Republican. In November 2008, Cantor was elected as the House Minority Whip, the first Jewish Republican to be selected for the position.[28]

In the 2000 presidential election, Joe Lieberman was the first American Jew to run for national office on a major party ticket when he was chosen as Democratic presidential candidate Al Gore's vice-presidential nominee.

Participation in civil rights movements

As a group, American Jews have been very active in fighting prejudice and discrimination, and have historically been active participants in civil rights movements. In the mid-twentieth century, American Jews were among the most active participants and supporters of the black civil rights movement. Contemporaneously, Betty Friedan wrote her 1963 book The Feminine Mystique, which is sometimes credited with sparking the second wave of feminism, and was the first of many prominent American Jewish feminists which extended into the feminist third wave. American Jews have also since its founding been largely supportive of and active figures in the struggle for gay rights in America.

Seymour Siegel suggests that the historic struggle against prejudice faced by Jews led to a natural sympathy for any people confronting discrimination. Joachim Prinz, president of the American Jewish Congress, stated the following when he spoke from the podium at the Lincoln Memorial during the famous March on Washington on August 28, 1963: "As Jews we bring to this great demonstration, in which thousands of us proudly participate, a twofold experience—one of the spirit and one of our history... From our Jewish historic experience of three and a half thousand years we say: Our ancient history began with slavery and the yearning for freedom. During the Middle Ages my people lived for a thousand years in the ghettos of Europe... It is for these reasons that it is not merely sympathy and compassion for the black people of America that motivates us. It is, above all and beyond all such sympathies and emotions, a sense of complete identification and solidarity born of our own painful historic experience. "[29][30]

The Holocaust

During the World War II period, the American Jewish community was bitterly and deeply divided and was unable to form a common front. Most Eastern Europeans favored Zionism, which saw a homeland as the only solution; this had the effect of diverting attention from the horrors in Nazi Germany. German Jews were alarmed at the Nazis but were disdainful of Zionism. Proponents of a Jewish state and Jewish army agitated, but many leaders were so fearful of an antisemitic backlash inside the U.S. that they demanded that all Jews keep a low public profile. One important development was the sudden conversion of most (but not all) Jewish leaders to Zionism late in the war.[31] The Holocaust was largely ignored by American media as it was happening.

The Holocaust had a profound impact on the community in the United States, especially after 1960, as Jews tried to comprehend what had happened, and especially to commemorate and grapple with it when looking to the future. Abraham Joshua Heschel summarized this dilemma when he attempted to understand Auschwitz: "To try to answer is to commit a supreme blasphemy. Israel enables us to bear the agony of Auschwitz without radical despair, to sense a ray [of] God's radiance in the jungles of history."[32]

International affairs

Jews began taking a special interest in international affairs in the early twentieth century, especially regarding pogroms in Imperial Russia, and restrictions on immigration in the 1920s. Political Zionism became a well-organized movement in the U.S. with the involvement of Louis Brandeis and the British promise of a homeland in the Balfour Declaration of 1917.[33] Jewish Americans organized large-scale boycotts of German merchandise during the 1930s, to protest the Nazi rule in Germany. Franklin D. Roosevelt's leftist domestic policies received strong Jewish support in the 1930s and 1940s, as did his anti-Nazi foreign policy and his promotion of the United Nations. Support for political Zionism in this period, although growing in influence, remained a distinctly minority opinion among German Jews until about 1944-45. The founding of Israel in 1948 made the Middle East a center of attention; the immediate recognition of Israel by the American government was an indication of both its intrinsic support and the influence of political Zionism.

This attention initially was based on a natural and religious affinity toward and support for Israel and world Jewry. The attention is also because of the ensuing and unresolved conflicts regarding the founding Israel and Zionism itself. A lively internal debate commenced, following the Six-Day War. The American Jewish community was divided over whether or not they agreed with the Israeli response; the great majority came to accept the war as necessary. A tension existed especially for some Jews on the left who saw Israel as too anti-Soviet and anti-Palestinian.[34] Similar tensions were aroused by the 1977 election of Begin and the rise of revisionist policies, the 1982 Lebanon War and the continuing occupation of the West Bank and Gaza.[35] Disagreement over Israel’s 1993 acceptance of the Oslo Accords caused a further split among American Jews;[36] this mirrored a similar split among Israelis and led to a parallel rift within the pro-Israel lobby.[37]

Abandoning any pretense of unity, both segments began to develop separate advocacy and lobbying organizations. The liberal supporters of the Oslo Accord worked through Americans for Peace Now (APN), Israel Policy Forum (IPF) and other groups friendly to the Labour government in Israel. They tried to assure Congress that American Jewry was behind the Accord and defended the efforts of the administration to help the fledgling Palestinian authority (PA) including promises of financial aid. In a battle for public opinion, IPF commissioned a number of polls showing widespread support for Oslo among the community. In opposition to Oslo, an alliance of Orthodox groups, such as ZOA, Americans For a Safe Israel (AFSI), and the Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs (JINSA) launched a major public opinion campaign. On 10 October 1993, the opponents of the Palestinian-Israeli accord, organized at the American Leadership Conference for a Safe Israel, where they warned that Israel was prostrating itself before a “an armed thug”, and predicted and that the “thirteenth of September is a date that will live in infamy”. Hard-core Zionists also criticized, often in harsh language, Prime Minister Rabin and Shimon Perez, his foreign minister and chief architect of the peace accord. With the community so strongly divided, AIPAC and the Presidents Conference, which was tasked with representing the national Jewish consensus, struggled to keep the increasingly shrill discourse civil. Reflecting these tensions, Abraham Foxman from the Jewish Anti-defamation League was forced by the conference to apologize for bad mouthing ZOA’s Klein. The Conference, which under its organizational guidelines was in charge of moderating communal discourse, reluctantly censured some Orthodox spokespeople for attacking Colette Avital, the labor-appointed Israel Council General in New York and an ardent supporter of the peace process.

</ref>[38]

A 2004 poll indicated that a majority of Jewish Americans favor the creation of an independent Palestinian state and believe that Israel should remove some or all of its settlements from the West Bank.[39] Despite Israeli security being among the motivations for American intervention in Iraq, Jews were less supportive of the Iraq War than Americans as a whole.[40] At the beginning of the conflict, Arab Americans were more supportive of the Iraq War than American Jews were (although both groups were less supportive of it than the general population).

Population

The Jewish population of the United States is either the largest in the world, or second to that of Israel, depending on the sources and methods used to measure it.

Precise population figures vary depending on whether Jews are accounted for based on halakhic considerations, or secular, political and ancestral identification factors. There were about 4 million adherents of Judaism in the U.S. as of 2001, approximately 1.4% of the US population.[41] The community self-identifying as Jewish by birth, irrespective of halakhic (unbroken maternal line of Jewish descent or formal Jewish conversion) status, numbers about 7 million, or 2.5% of the US population. According to the Jewish Agency, for the year 2007 Israel is home to 5.4 million Jews (40.9% of the world's Jewish population), while the United States contained 5.3 million (40.2%).[42]

The most recent large scale population survey, released in the 2006 American Jewish Yearbook population survey estimates place the number of American Jews at 6.4 million, or approximately 2.1% of the total population. This figure is significantly higher than the previous large scale survey estimate, conducted by the 2000–2001 National Jewish Population estimates, which estimated 5.2 million Jews. A 2007 study released by the Steinhardt Social Research Institute (SSRI) at Brandeis University presents evidence to suggest that both of these figures may be underestimations with a potential 7.0–7.4 million Americans of Jewish descent.[43] Jews in the U.S. settled largely in and near the major cities. The Ashkenazi Jews, who are now the vast majority of American Jews, settled first in the Northeast and Midwest cities, but in recent decades increasingly in the South and West. Within the metropolitan areas of New York City, Los Angeles, and Miami lives nearly one quarter the world's Jews.[44]

Significant Jewish population centers

| Rank (WJC)[44] | Rank (ARDA)[45] | Metro area | Number of Jews (WJC) | Number of Jews (ASARB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | New York City | 1,750,000 | 2,028,200 |

| 2 | 3 | Miami | 535,000 | 337,000 |

| 3 | 2 | Los Angeles | 490,000 | 662,450 |

| 4 | 4 | Philadelphia | 254,000 | 285,950 |

| 5 | 6 | Chicago | 248,000 | 265,400 |

| 6 | 8 | San Francisco | 210,000 | 218,700 |

| 7 | 7 | Boston | 208,000 | 261,100 |

| 8 | 5 | Baltimore-Washington | 165,000 | 276,445 |

| Rank | State | Percent Jewish |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | New York | 9.1 |

| 2 | New Jersey | 5.5 |

| 3 | Florida | 4.6 |

| 4 | District of Columbia | 4.5 |

| 5 | Massachusetts | 4.4 |

| 6 | Maryland | 4.2 |

| 7 | Connecticut | 3.0 |

| 8 | California | 2.9 |

| 9 | Pennsylvania | 2.7 |

| 10 | Illinois | 2.3 |

Although New York is the second largest Jewish population center in the world, (after the Gush Dan metropolitan area in Israel),[44] the Miami metropolitan area has a slightly greater Jewish population on a per-capita basis (9.9% compared to metropolitan New York's 9.3%). Several other major cities have large Jewish communities, including Baltimore, Boston, Chicago and Philadelphia. In many metropolitan areas, the majority of Jewish families live in suburban areas. The Greater Phoenix area was home to about 83,000 Jews in 2002, and has been rapidly growing.[46]

The Israeli immigrant community in America is less widespread. The significant Israeli immigrant communities in the United States are in Los Angeles, New York City, Miami, and Chicago.[47]

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development calculated an 'expatriate rate' of 2.9 persons per thousand, putting Israel in the mid-range of expatriate rates among the 175 OECD countries examined in 2005.[48]

According to the 2001 undertaking of the National Jewish Population Survey, 4.3 million American Jews have some sort of strong connection to the Jewish community, whether religious or cultural.

Assimilation and population changes

These parallel themes have facilitated the extraordinary economic, political, and social success of the American Jewish community, but also have contributed to widespread cultural assimilation.[49] More recently however, the propriety and degree of assimilation has also become a significant and controversial issue within the modern American Jewish community, with both political and religious skeptics.[50].

While not all Jews disapprove of intermarriage, many members of the Jewish community have become concerned that the high rate of interfaith marriage will result in the eventual disappearance of the American Jewish community. Intermarriage rates have risen from roughly 6% in 1950 to approximately 40–50% in the year 2000.[51][52] Only about 33% of intermarried couples raise their children with a Jewish religious upbringing. This, in combination with the comparatively low birthrate in the Jewish community, has led to a 5% decline in the Jewish population of the United States in the 1990s.[52] In addition to this, when compared with the general American population, the American Jewish community is slightly older.[52]

Despite the fact that only 33% of intermarried couples provide their children with a Jewish upbringing, doing so is more common among intermarried families raising their children in areas with high Jewish populations.[53] The Boston area, for example, is exceptional in that an estimated 60% percent of children of intermarriages are being raised Jewish, meaning that intermarriage would actually be contributing to a net increase in the number of Jews.[54] As well, some children raised through intermarriage rediscover and embrace their Jewish roots when they themselves marry and have children.

In contrast to the ongoing trends of assimilation, some communities within American Jewry, such as Orthodox Jews, have significantly higher birth rates and lower intermarriage rates, and are growing rapidly. The proportion of Jewish synagogue members who were Orthodox rose from 11% in 1971 to 21% in 2000, while the overall Jewish community declined in number. [55] In 2000, there were 360,000 so-called "ultra-orthodox" (Haredi) Jews in USA (7.2%).[56] The figure for 2006 is estimated at 468,000 (9.4%).[56]

About half of the American Jews are considered to be religious. Out of this 2,831,000 religious Jewish population, 92% are non-Hispanic white, 5% Hispanic (of any race) (Most commonly from Argentina, Venezuela, or Cuba; many are Hispanics who converted after finding out they are descendants of Jews forced to convert to Roman Catholicism during the Spanish Inquisition. See Hispanic#Religious diversity), 1% Asian (Mostly Bukharian and Persian Jews), 1% Black and 1% Other (Mixed Race.etc.). Almost this many non-religious Jews exist in United States, the proportion of Whites being higher than that among the religious population.[57]

African American Jews and other American Jews of African descent

The American Jewish community includes African American Jews and other American Jews of African descent (such as American Beta Israel), excluding North African Jewish Americans, who are considered Mizrahi or Sephardi. Estimates of the number of American Jews of African descent in the United States range from 20,000[58] to 200,000.[59] Jews of African descent belong to all of American Jewish denominations. Like their white Jewish counterparts, some black Jews are Jewish atheists or ethnic Jews.

Relations between American Jews of African descent and other Jewish Americans are generally cordial. There are, however, some tensions with a specific minority among African-Americans who consider themselves (but not Ashkenazi Jews) to be the true descendants of the Israelites of the Torah. They are generally not considered to be members of the mainstream Jewish community, since they have not formally converted to Judaism, nor are they ethnically related to other Jews. One such group, the African Hebrew Israelites of Jerusalem, emigrated to Israel and was granted permanent residency status there.

Notable African-American Jews include Lisa Bonet, Sammy Davis, Jr., Yaphet Kotto, Jordan Farmar, and rabbis Capers Funnye and Alysa Stanton.

Religion

Jewishness is sometimes considered an ethnic identity as well as a religious one. See Ethnoreligious group.

Observances and engagement

Jewish religious practice in America is quite varied. Among the 4.3 million American Jews described as "strongly connected" to Judaism, over 80% report some sort of active engagement with Judaism, ranging from attendance at daily prayer services on one end of the spectrum to as little as attendance Passover Seders or lighting Hanukkah candles on the other.

A 2003 Harris Poll found that 16% of American Jews go to the synagogue at least once a month, 42% go less frequently but at least once a year, and 42% go less frequently than once a year.[60]

About one-sixth of American Jews maintain kosher dietary standards.[61]

The survey found that of the 4.3 million strongly connected Jews, 46% belong to a synagogue. Among those households who belong to a synagogue, 38% are members of Reform synagogues, 33% Conservative, 22% Orthodox, 2% Reconstructionist, and 5% other types. Traditionally, Sephardic and Mizrahis do not have different branches (Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, etc.) but usually remain observant and religious. The survey discovered that Jews in the Northeast and Midwest are generally more observant than Jews in the South or West. Reflecting a trend also observed among other religious groups, Jews in the Northwestern United States are typically the least observant.

In recent years, there has been a noticeable trend of secular American Jews returning to a more observant, in most cases, Orthodox, lifestyle. Such Jews are called baalei teshuva ("returners", see also Repentance in Judaism). It is uncertain how widespread or demographically important this movement is at present.

The 2008 American Religious Identification Survey found that around 3.4 million American Jews call themselves religious — out of a general Jewish population of about 5.4 million. The number of Jews who identify themselves as only culturally Jewish has risen from 20% in 1990 to 37% last year, according to the study. In the same period, the number of all US adults who said they had no religion rose from 8% to 15%. Jews are more likely to be secular than Americans in general, the researchers said. About half of all US Jews — including those who consider themselves religiously observant — claim in the survey that they have a secular worldview and see no contradiction between that outlook and their faith, according to the study's authors. Researchers attribute the trends among American Jews to the high rate of intermarriage and "disaffection from Judaism" in the United States.[62]

Religious beliefs

American Jews are more likely to be atheist or agnostic than most Americans, especially so compared with Protestants or Catholics. A 2003 poll found that while 79% of Americans believe in God, only 48% of American Jews do, compared with 79% and 90% for Catholics and Protestants respectively. While 66% of Americans said they were "absolutely certain" of God's existence, 24% of American Jews said the same. And though 9 percent of Americans believe there is no God (8% Catholic and 4% Protestant), 19 percent of American Jews believe God does not exist.[60]

Education

The great majority of school-age Jewish students attend public schools, although Jewish day schools and yeshivas are to be found throughout the country. Jewish cultural studies and Hebrew language instruction is also commonly offered at synagogues in the form of supplementary Hebrew schools or Sunday schools.

Until the 1950s, a quota system at elite colleges and universities limited the number of Jewish students. Before 1945, only a few Jewish professors were permitted as instructors at elite universities. In 1941, antisemitism drove Milton Friedman from a non-tenured assistant professorship at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.[63] Harry Levin became the first Jewish full professor in the Harvard English department in 1943, but the Economics department decided not to hire Paul Samuelson in 1948. Harvard hired its first Jewish biochemists in 1954.[64] A third of the total student body at Harvard is now Jewish-American.[65]

Today, American Jews no longer face the discrimination in higher education that they did in the past, particularly in the Ivy League. For example, by 1986, a third of the presidents of the elite undergraduate clubs at Harvard were Jewish.[63] Rick Levin has been president of Yale University since 1993, Judith Rodin was president of the University of Pennsylvania from 1994 to 2004 (and is currently president of Rockefeller University), and Paul Samuelson's nephew, Lawrence Summers, was president of Harvard University from 2001 until 2006.

Public Universities

|

Private Universities

|

"Hillel's Top 10 Jewish Schools". Hillel. Hillel.org. February 16, 2006. http://www.hillel.org/about/news/2006/feb/20060216_top.htm. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

There are an estimated 4,000 Jewish students at the University of California, Berkeley.[70]

Contemporary politics

Today, American Jews are a distinctive and influential group in the nation's politics. Jeffrey S. Helmreich writes that the ability of American Jews to effect this through political or financial clout is overestimated,[71] that the primary influence lies in the group's voting patterns.[21]

"Jews have devoted themselves to politics with almost religious fervor," writes Mitchell Bard, who adds that Jews have the highest percentage voter turnout of any ethnic group. While 2–2.5% of the United States population is Jewish, 94% live in 13 key electoral college states, which combined have enough electors to elect the president.[72][73] Though the majority (60–70%) of the country's Jews identify as Democratic, Jews span the political spectrum and Helmreich describes them as "a uniquely swayable bloc" as a result of Republican stances on Israel.[21][73][74] A paper by Dr. Eric Uslaner of the University of Maryland disagrees, at least with regard to the 2004 election: "Only 15% of Jews said that Israel was a key voting issue. Among those voters, 55% voted for Kerry (compared to 83% of Jewish voters not concerned with Israel)." The paper goes on point out that negative views of Evangelical Christians had a distinctly negative impact for Republicans among Jewish voters, while Orthodox Jews, traditionally more conservative in outlook as to social issues, favored the Republican Party.[75] A New York Times article suggests that the Jewish movement to the Republican party is focused heavily on faith-based issues, similar to the Catholic vote, which is credited for helping President Bush taking Florida in 2004.[76]

Though critics have charged that Jewish interests were partially responsible for the push to war with Iraq, Jewish Americans were actually more strongly opposed to the Iraq war from its onset than any other major religious group or even most Americans. The greater opposition to the war was not simply a result of high Democratic identification among U.S. Jews, as Jews of all political persuasions were more likely to oppose the war than non-Jews who shared the same political leanings.[77][78]

Owing to high Democratic identification in the 2008 United States Presidential Election, 78% of Jews voted for Democrat Barack Obama versus 21% for Republican John McCain, despite Republican attempts to connect Obama to Muslim and pro-Palestinian causes.[79] It has been suggested that running mate Sarah Palin's conservative views on social issues may have nudged Jews away from the McCain-Palin ticket.[21][79]

American Jews are largely supportive of gay rights, though a split exists within the group by observance. Reform rabbis in America perform same-sex marriages as a matter of routine, and there are fifteen LGBT Jewish congregations in North America.[80] Reform, Reconstructionist and, increasingly, Conservative, Jews are far more supportive on issues like gay marriage than Orthodox Jews are.[81] A 2007 survey of Conservative Jewish leaders and activists showed that an overwhelming majority supported gay rabbinical ordination and same-sex marriage.[82] Accordingly, 78% percent of Jewish voters rejected Proposition 8, the bill that banned gay marriage in California. No other ethnic or religious group voted as strongly against it.[83]

Jews in America also overwhelmingly oppose current United States marijuana policy. Eighty-six percent of Jewish Americans opposed arresting nonviolent marijuana smokers, compared to 61% for the population at large and 68% of all Democrats. Additionally, 85% of Jews in the United States opposed using federal law enforcement to close patient cooperatives for medical marijuana in states where medical marijuana is legal, compared to 67% of the population at large and 73% of Democrats.[84]

Jewish American culture

Since the time of the last major wave of Jewish immigration to America (over 2,000,000 Eastern European Jews who arrived between 1890 and 1924), Jewish secular culture in the United States has become integrated in almost every important way with the broader American culture. Many aspects of Jewish American culture have, in turn, become part of the wider culture of the United States.

Language

Most American Jews are today native English-speakers. A variety of other languages are still spoken within some American Jewish communities, communities that are representative of the various Jewish ethnic divisions from around the world that have come together to make up America's Jewish population.

Many of America's Hasidic Jews (being exclusively of Ashkenazi descent) are raised speaking Yiddish. Yiddish was once spoken as the primary language by most of the several million European Jews who immigrated to the United States (it was, in fact, the original language in which The Forward was published). Yiddish has had an influence on American English, and words borrowed from it include chutzpah ("effrontery", "gall"), nosh ("snack"), schlep ("drag"), schmuck ("fool", literally "penis"), and, depending on ideolect, hundreds of other terms. (See also Yinglish.)

The Persian Jewish community in the United States, notably the large community in and around Los Angeles and Beverly Hills, California, primarily speak Persian (see also Judeo-Persian) in the home and synagogue. They also support their own Persian language newspapers. Persian Jews also reside in eastern parts of New York such as Kew Gardens and Great Neck, Long Island.

Many recent Jewish immigrants from the Soviet Union speak primarily Russian at home, and there are several notable communities where public life and business are carried out mainly in Russian, such as in Brighton Beach in New York City and Sunny Isles Beach in Miami.

American Bukharan Jews speak Bukhori (a dialect of Persian) and Russian. They publish their own newspapers such as the Bukharian Times and a large portion live in Queens, New York. Forest Hills in the New York City borough of Queens is home to 108th Street, which is called by some "Bukharian Broadway",[85] a reference to the many stores and restaurants found on and around the street that have Bukharian influences. Many Bukharians are also represented in parts of Arizona, Miami, Florida, and areas of Southern California such as San Diego.

Classical Hebrew is the language of most Jewish religious literature, such as the Tanakh (Bible) and Siddur (prayerbook). Modern Hebrew is also the primary official language of the modern State of Israel, which further encourages many to learn it as a second language. Some recent Israeli immigrants to America speak Hebrew as their primary language.

Some Jews, particularly in Miami and Los Angeles, immigrated from Latin America. Many of these Hispanic Jews (many of them of Sephardic origin dating back to the Spanish and Portuguese colonial era, but also some from Ashkenazi descent from recent Central and Eastern European immigration to Latin America) speak Spanish in the home, and some have intermarried with the non-Jewish Hispanic population. Recent Jews from Spain speak Spanish, and Spanish may be spoken by other Jews with ancestry outside Spain and Latin America but who live in areas near predominantly Hispanic populations. There are a large number of synagogues in the Miami area that give services in Spanish. Many Luso-Jews with origin from Brazil and Portugal (Sephardic Jews but including in Brazil, Sephardic Jews with Spanish origin, Ashkenazi, and Mizrahi) speak Portuguese in home. There are a handful of older European immigrant communities that still speak Ladino.

Jewish American literature

Although American Jews have contributed greatly to American arts overall, there remains a distinctly Jewish American literature. Jewish American literature often explores the experience of being a Jew in America, and the conflicting pulls of secular society and history.

Notable American Jews

Popular culture

Many individual Jews have made significant contributions to American popular culture. There have been many Jewish American actors and performers, ranging from early 1900s actors, to classic Hollywood film stars, and culminating in many currently known actors. Many of the early Hollywood moguls and pioneers were Jewish.

The field of American comedy includes many Jews. The legacy also includes songwriters and authors. Many Jews have been at the forefront of women's issues. Jews have also done well in the field of sport.

Government and military

Since 1845, a total of 34 Jews have served in the Senate, including the 14 present-day senators noted above. Judah P. Benjamin was the first practicing Jewish Senator, and would later serve as Confederate Secretary of War and Secretary of State during the Civil War. Rahm Emmanuel serves as Chief of Staff to President Barack Obama. The number of Jews elected to the House rose to an all-time high of 30. Seven Jews have been appointed to the United States Supreme Court.

In April 1984, an unusual historic connection between American history and American Jewish history was made when President Ronald Reagan read Jewish Navy chaplain Arnold Resnicoff's eyewitness account of the 1983 Beirut barracks bombing as his keynote speech to the Rev. Jerry Falwell's Baptism Fundamentalism '84 Washington, DC, convention.[86]

Sixteen American Jews have been awarded the Medal of Honor.

World War II

More than 550,000 Jews served in the U.S. military during World War II; about 11,000 were killed and more than 40,000 were wounded. There were three recipients of the Medal of Honor, 157 recipients of the Army Distinguished Service Medal, Navy Distinguished Service Medal, Distinguished Service Cross, or Navy Cross, and about 1600 recipients of the Silver Star. About 50,000 other decorations. citations and awards were given to Jewish military personnel, for a total of 52,000 decorations. During this period, Jews were approximately 3.3 percent of the total U.S. population but constituted about 4.23 percent of the U.S. armed forces. About 60 percent of all Jewish physicians in the United States under 45 years of age were in service as military physicians and medics.[87]

Many Jewish physicists, including project lead J. Robert Oppenheimer, were involved in the Manhattan Project, the secret World War II effort to develop the atomic bomb. Many of these were refugees from Nazi Germany or from antisemitic persecution elsewhere in Europe.

Finance

American Jews in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries played a major role in American finance or "Wall Street", both at investment banks and investment funds.[88] German Jewish bankers began to assume an important role in American finance in the 1830s when government and private borrowing to pay for canals, railroads and other internal improvement increased rapidly and significantly. Men such as August Belmont (Rothschild's agent in New York and a leading Democrat), Philip Speyer, Jacob Schiff (at Kuhn, Loeb & Company), Joseph Seligman, Philip Lehman (of Lehman Brothers), Jules Bache, and Marcus Goldman (of Goldman Sachs) illustrate this financial elite.[89] As was true of their non-Jewish counterparts, family, personal, and business connections, a reputation for honesty and integrity, ability, and a willingness to take calculated risks were essential to recruit capital from widely scattered sources. The families and the firms which they controlled were bound together by religious and social factors, and by the prevalence of intermarriage. These personal ties fulfilled real business functions before the advent of institutional organization in the 20th century.[90][91] Nevertheless, antisemitic elements often falsely targeted them as key players in a supposed Jewish cabal conspiring to dominate the world.[92]

Since the late 20th century have Jews played a major role in the hedge fund industry, according to Zuckerman (2009)[93] Thus SAC Capital Advisors[94] , Soros Fund Management[95] , Och-Ziff Capital Management[96], GLG Partners[97] and Renaissance Technologies[98] are large hedge funds cofounded by Jews. They have also played a pivotal role in the private equity industry, co-founding some of the largest firms, such as Blackstone[99], Carlyle Group[100] , Warburg Pincus[101], and KKR.[102][103][104]

Federal Reserve

Paul Warburg, one of the leading advocates of the establishment of a central bank in the U.S. and one of the first governors of the newly established Federal Reserve System, came from a prominent Jewish family in Germany[105]. Several Jews have served as chairmen of the Fed, including Ben Bernanke, the current Chairman, and Alan Greenspan, the prior chairman.

Science, business, and academia

Jews have traditionally been drawn to business and academia (see Secular Jewish culture for some of the causes), and have made major contributions in science, economics, and the humanities. Of American Nobel Prize winners, 37 percent have been Jewish Americans (19 times the percentage of Jews in the population), as have been 71 percent of the John Bates Clark Medal winners (thirty-five times the Jewish percentage). While Jewish Americans only constitute roughly 2.5 percent of the U.S. population, they occupied 7.7 percent of board seats at U.S. corporations.[106]

Since many jobs/careers in science, business, and academia generally pay well, Jewish Americans also tend to have a higher average income than most Americans. A 2008 Pew Research Center study found that "46 percent of Jews in the US make more than $100,000 a year."[107]

Distribution of Jewish-Americans

According to the Glenmary Research Center, which publishes Religious Congregations and Membership in the United States,[108] the 100 counties and independent cities in 2000 with the largest Jewish communities, based by percentage of total population, were:

|

|

Notes and references

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ The Association of Religion Data Archives | Maps & Reports

- ↑ US Census Bureau Statistical Abstract 2009, Table 74. For persons 18 years or older, based on the Religious Landscape Survey, a survey conducted in the summer of 2007. (The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, Washington, DC, ‘‘U.S. Religious Landscape Survey’’; released February 2008.)[2]

- ↑ US Census Bureau, USA Statistics in Brief--Population by Sex and Age, 2007. [3]

- ↑ US Census Bureau Statistical Abstract 2009, Table 76, Christian Church Adherents, 2000, and Jewish Population, 2008— States. The Jewish population includes Jews who define themselves as Jewish by religion as well as those who define themselves as Jewish in cultural terms. Data on Jewish population are based primarily on a compilation of individual estimates made by local Jewish federations (as reported in the American Jewish Yearbook). [4]

- ↑ Central Bureau of Statistics, Statistical Abstract of Israel, 2008, Table 2.2.[5]

- ↑ http://www.jewsinamerica.org/

- ↑ Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim Synagogue

- ↑ Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim Synagogue

- ↑ Alexander DeConde, Ethnicity, Race, and American Foreign Policy: A History], p.52

- ↑ Sarna, American Judaism (2004) p 284-5

- ↑ Seth Korelitz, "The Menorah Idea: From Religion to Culture, From Race to Ethnicity," American Jewish History 1997 85(1): 75–100. 0164-0178

- ↑ Steve Siporin, "Immigrant and Ethnic Family Folklore," Western States Jewish History 1990 22(3): 230–242. 0749-5471

- ↑ Peter Novick, The Holocaust in American Life (1999); Hilene Flanzbaum, ed. The Americanization of the Holocaust (1999); Monty Noam Penkower, "Shaping Holocaust Memory," American Jewish History 2000 88(1): 127–132. 0164-0178

- ↑ http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/US-Israel/jewvote.html

- ↑ Ronald H. Bayor, Neighbors in Conflict: The Irish, Germans, Jews and Italians of New York City, 1929-1941 (1978)

- ↑ See Murray Friedman, What Went Wrong? The Creation and Collapse of the Black-Jewish Alliance. (1995)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Hasia Diner, The Jews of the United States. 1654 to 2000 (2004), ch 5

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 "Jewish Vote In Presidential Elections". American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/US-Israel/jewvote.html. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ↑ Abba Hillel Silver

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 Jeffrey S. Helmreich. "THE ISRAEL SWING FACTOR: HOW THE AMERICAN JEWISH VOTE INFLUENCES U.S. ELECTIONS". http://www.jcpa.org/jl/vp446.htm. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ .2004 exit polls at CNN

- ↑ OP-ED: Why Jews voted for Obama by Marc Stanley, Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA), November 5, 2008 (retrieved on December 6, 2008).

- ↑ CNN Exit Poll

- ↑ 2006 exit polls at

- ↑ Most Jews ever set to enter Congress | International News | Jerusalem Post

- ↑ See Ynet News at

- ↑ What is the future for Republican Jews? by Eric Fingerhut, Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA), November 25, 2008.

- ↑ Joachim Prinz March on Washington Speech

- ↑ Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement - March on Washington

- ↑ Henry L. Feingold, A Time for Searching: Entering the Mainstream, 1920–1945 (1992), pp 225–65

- ↑ Staub (2004) p.80

- ↑ Melvin I. Urofsky, Louis D. Brandeis: A Life (2009) p. 515

- ↑ Staub (2004)

- ↑ Roberta Strauss Feuerlicht. “The Fate of the Jews, A people torn between Israeli Power and Jewish Ethics”. Times Books, 1983. ISBN 0812910605

- ↑ Ofira Seliktar, "The Changing Identity of American Jews, Israel and the Peace Process," in Danny Ben-Moshe and Zohar Segev, eds. Israel, the Diaspora, and Jewish Identity, (2007) p126 [6].

The 1993 Oslo Agreement made this split in the Jewish community official. Prime Minister Yitzak Rabin’s handshake with Yasir Arafat during the 13 September White House ceremony elicited dramatically opposed reactions among American Jews. To the liberal universalists the accord was highly welcome news. As one commentator put it, after a year of tension between Israel and the United States, “there was an audible sigh of relief from American and Jewish liberals. Once again, they could support Israel as good Jews, committed liberals, and loyal Americans.” The community “could embrace the Jewish state, without compromising either its liberalism or its patriotism”. Hidden deeper in this collective sense of relief was the hope that, following the peace with the Palestinians, Israel would transform itself into a Western-style liberal democracy, featuring a full separation between the state and religion. Not accidentally, many of the leading advocates of Oslo, including the Yossi Beilin, the then Deputy Foreign Minister, cherish the belief that a “normalized” Israel would become less Jewish and more democratic. However, to the hard-core Zionists in the Orthodox community and among right wing Jews, the peace treaty amounted to what some dubbed the “handshake earthquake.” From the perspective of the Orthodox, Oslo was not just an affront to the sanctity of Eretz Yisrael, but also a personal threat to the Orthodox settlers—often kin or former congregants—in the West Bank and Gaza. For Jewish nationalists such as Morton Klein, the president of the Zionist organization of America, and Norman Podhoretz, the editor of Commentary, the peace treaty amounted to an appeasement of Palestinian terrorism. They and others repeatedly warned that the newly established Palestinian Authority (PA) would pose a serious security threat to Israel.

- ↑ Ofira Seliktar, "The Changing Identity of American Jews, Israel and the Peace Process," in Danny Ben-Moshe and Zohar Segev, eds. Israel, the Diaspora, and Jewish Identity, (2007) p126

- ↑ Middle East Review of International Affairs , Journal, Volume 6, No. 1 - March 2002, Scott Lasensky, Underwriting Peace in the Middle East: U.S. Foreign Policy and the Limits of Economic Inducements

The Palestinian aid effort was certainly not helped by the heated debate that quickly developed inside the Beltway. Not only was the Israeli electorate divided on the Oslo accords, but so, too, was the American Jewish community, particularly at the leadership level and among the major New York and Washington-based public interest groups. U.S. Jews opposed to Oslo teamed up with Israelis "who brought their domestic issues to Washington" and together they pursued a campaign that focused most of its attention on Congress and the aid program. The dynamic was new to Washington. The Administration, the Rabin-Peres government, and some American Jewish groups teamed on one side while Israeli opposition groups and anti-Oslo American Jewish organizations pulled Congress in the other direction.

- ↑ Mideast Dispatch Archive: Iraq war leads Jewish voters to Kerry, poll finds (and other items)

- ↑ Poll: Jews against Iraq war - Jewish News of Greater Phoenix

- ↑ ARIS Key Findings at http://www.gc.cuny.edu/faculty/research_briefs/aris/key_findings.htm

- ↑ Pfeffer, Anshel. "Jewish Agency: 13.2 million Jews worldwide on eve of Rosh Hashanah, 5768". Haaretz Daily Newspaper Israel. http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/903585.html. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ↑ Brandeis University Study Finds that American-Jewish Population is Significantly Larger than Previously Thought - Press Release

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 "The Largest Jewish Communities". adherents.com. http://www.adherents.com/largecom/com_judaism.html. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ↑ "Judaism (estimated) Metro Areas (2000)". The Association of Religion Data Archives. http://www.thearda.com/QuickLists/QuickList_195c.asp. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ↑ 2002 Greater Phoenix Jewish Community StudyPDF

- ↑ Gold, Steven; Phillips, Bruce (1996). "Israelis in the United States" (PDF). American Jewish Yearbook, 1996 96: 51–101. http://www.ajcarchives.org/AJC_DATA/Files/1996_3_SpecialArticles.pdf

- ↑ "Database on immigrants and expatriates:Emigration rates by country of birth (Total population)". Organisation for Economic Co-ordination and Development, Statistics Portal. http://www.oecd.org/document/51/0,3343,en_2825_494553_34063091_1_1_1_1,00.html. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- ↑ Postrel, Virginia (May 1993). Uncommon Culture. Reason Magazine. http://www.reason.com/news/show/29368.html. Retrieved 2007-10-05.

- ↑ Bela Vago, Marsha L. Rozenblit, "Review of Jewish Assimilation in Modern Times"PDF, Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 44, No. 3/4 (Summer–Autumn, 1982), pp. 334–335.

Religious Jews regarded those who assimilated with horror, and Zionists campaigned against assimilation as an act of treason.

- ↑ http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/rcah/html/ah_047702_religiouscul.htm

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 http://www.jewishla.org/news/html/populationdrop.html

- ↑ Michael Paulson (2006-11-10). "Jewish population in region rises". Boston Globe. http://www.boston.com/news/local/articles/2006/11/10/jewish_population_in_region_rises/. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- ↑ http://cjp.org/getfile.asp?id=16072

- ↑ The Future of Judaism - January 25, 2005 - The New York Sun

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 'Majority of Jews will be Ultra-Orthodox by 2050' (The University of Manchester)

- ↑ ARIS 2001PDF (449 KB)

- ↑ David Whelan (2003-05-08). "A Fledgling Grant Maker Nurtures Young Jewish 'Social Entrepreneurs'". The Chronicle of Philanthropy. http://philanthropy.com/jobs/2003/05/15/20030515-359473.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

- ↑ Michael Gelbwasser (1998-04-10). "Organization for black Jews claims 200,000 in U.S.". j.. http://www.jweekly.com/article/full/8029/organization-for-black-jews-claims-200-000-in-u-s/. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 While Most Americans Believe in God, Only 36% Attend a Religious Service Once a Month or More Often

- ↑ Stern, the author of How to Keep Kosher: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding Jewish Dietary Laws, is one of a million or so American Jews (out of around six million total) who keeps her kitchen year-round according to the laws of kashruth, or kosher.

- ↑ http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-3759000,00.html

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Milton Friedman and Rose D. Friedman, Two Lucky People: Memoirs (1998) p. 58 online

- ↑ Morton Keller, Making Harvard Modern: The Rise of America's University. (2001), pp 75, 82, 97, 212, 472.

- ↑ Hillel. Hillel.org, http://www.hillel.org/about/news/2006/feb/20060216_top.htm. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Hillel's Top 10 Jewish Schools

- ↑ Brandeis University

- ↑ Northwestern University

- ↑ Washington University

- ↑ https://www.policyarchive.org/bitstream/handle/10207/10679/JJCS71-4-04.pdf?sequence=1

- ↑ Steven L. Spiegel, The Other Arab-Israeli Conflict (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985), pp. 150–165.

- ↑ Mitchell Bard. "The Israeli and Arab Lobbies". The American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/US-Israel/lobby.html. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Sophia Tareem. "Family ties: Obama counts rabbi among relatives". Associated Press. http://ap.google.com/article/ALeqM5gr3Tlt4jLh-22i1pjxPpAe5ULeWgD9380CUO1. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- ↑ "Busting the Myth: Jews Remain Democrats, New Independent Polling Shows". National Jewish Democratic Council. http://www.njdc.org/media/entry/busting_the_myth_jews_remain_democrats_new_independent_polling_shows. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ Eric M. Uslaner, "Two Front War: Jews, Identity, Liberalism, and Voting"PDF (59.6 KB)

- ↑ The New York Times > Washington > Election 2004 > Faith Groups: Bush Benefits From Efforts to Build a Coalition of the Faithful

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Jones. "Among Religious Groups, Jewish Americans Most Strongly Oppose War". Gallup, Inc.. http://www.gallup.com/poll/26677/Among-Religious-Groups-Jewish-Americans-Most-Strongly-Oppose-War.aspx. Retrieved 2008-10-04.

- ↑ "Editor's Comments" (PDF). Near East. http://www.aipac.org/Publications/AIPACPeriodicalsNearEastReport/NER011507.pdf. Retrieved 2008-10-04.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Yitzhak Benhorin. "78% of American Jews vote Obama". Yedioth Internet. http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-3618408,00.html. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ↑ "The gay question and the Jewish question". haaretz. http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/798787.html. Retrieved 2010-01-06.

- ↑ Attacks on Gay Rights: How Jews See It

- ↑ Rebecca Spence. "Poll: Conservative Leaders Back Gay Rabbis". Forward Association. http://www.forward.com/articles/9989/. Retrieved 2009-04-23.

- ↑ "L.A. Jews overwhelmingly opposed Prop. 8, exit poll finds". LA Times. 2008-11-09. http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/lanow/2008/11/la-jews-overwhe.html. Retrieved 2008-12-10.

- ↑ "Majority of Americans Oppose US Marijuana Policies". NORML. http://norml.org/index.cfm?Group_ID=5052. Retrieved 2009-04-23.

- ↑ Moskin, Julia (2006-01-18). "The Silk Road Leads to Queens". The New York Times. http://travel.nytimes.com/2006/01/18/dining/18rego.html. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ↑ Speech: Ronald Reagan presidential speech:video version.

- ↑ Brody, Seymour. "Jewish Heroes and Heroines in America: World War II to the Present, A Judaica Collection Exhibit."

- ↑ "Banking and Bankers," Encyclopaedia Judaica. (2nd ed. 2008) online

- ↑ Stephen Birmingham, "Our Crowd": The Great Jewish Families of New York (1967) pp 8-9, 96-108, 128-42, 233-36, 331-37, 343,

- ↑ Vincent P. Carosso, "A Financial Elite: New York's German-Jewish Investment Bankers," American Jewish Historical Quarterly, 1976, Vol. 66 Issue 1, pp 67-88

- ↑ Barry E. Supple, "A Business Elite: German-Jewish Financiers in Nineteenth-Century New York," Business History Review, Summer 1957, Vol. 31 Issue 2, pp 143-177

- ↑ Richard Levy, ed. Bankers, Jewish" in Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution (2005) pp 55-56

- ↑ Bruce Zuckerman, The Jewish Role In American Life (2009) pp 64, 70

- ↑ Led by Steven Cohen; Bruce Zuckerman, The Jewish Role In American Life (2009) p. 71

- ↑ Bruce Zuckerman, The Jewish Role In American Life (2009) p. 72

- ↑ "Schechter school mourns founder Golda Och, 74" New Jersey Jewish News Jan. 13, 2010

- ↑ "The 400 Richest Americans: #355 Noam Gottesman" Forbes Sept 17. 1008

- ↑ Steven L. Pease. The Golden Age of Jewish Achievement (2009) p. 510

- ↑ See Jamie Johnson, "Wasps Stung over Renaming of the N.Y.P.L." Vanity Fair Daily May 19, 2008

- ↑ Robin Pogrebin, "Donor Gives Lincoln Center $10 Million", New York Times Sept. 30, 2009

- ↑ Ron Chernow, The Warburgs (1994) p. 661

- ↑ R. William Weisberger, "Jews and American Investment Banking," American Jewish Archives, June 1991, Vol. 43 Issue 1, pp 71-75

- ↑ On the careers of John Gutfreund (at Salomon Brothers); Felix Rohatyn (based at Lazard); Sanford I. Weill (of Citigroup) and numerous others see Judith Ramsey Ehrlich, The New Crowd: The Changing of the Jewish Guard on Wall Street (1990), pp. 4, 72, 226.

- ↑ Charles D. Ellis, The Partnership: The Making of Goldman Sachs (2nd ed. 2009) pp 29, 45, 52, 91, 93

- ↑ Ron Chernow, The Warburgs (1994) p. 26

- ↑ "Mother Jones, the Changing Power Elite, 1998". http://www.motherjones.com/news/feature/1998/03/zweigenhaft.html. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- ↑ New Study Claims US Jews Have Reasons to Be Proud - News Briefs - Arutz Sheva

- ↑ The Association of Religion Data Archives | Maps & Reports | Select Report

- ↑ Manhattan

- ↑ Brooklyn

- ↑ Staten Island

Bibliography

- American Jewish Committee. American Jewish Yearbook: The Annual Record of Jewish Civilization (annual, 1899–2009+),complete text online 1899–2007; long sophisticated essays on status of Jews in U.S. and worldwide; the standard primary source used by historians

- Norwood, Stephen H., and Eunice G. Pollack, eds. Encyclopedia of American Jewish history (2 vol 2007), 775pp; comprehenisive coverage by experts; excerpt and text search vol 1

- The Jewish People in America 5 vol 1992

- Faber, Eli. A Time for Planting: The First Migration, 1654–1820 (Volume 1) (1992) excerpt and text search

- Diner, Hasia R. A Time for Gathering: The Second Migration, 1820–1880 (Volume 2) (1992) excerpt and text search

- Sorin, Gerald. A Time for Building: The Third Migration, 1880–1920 (1992) excerpt and text search

- Feingold, Henry L. A Time for Searching: Entering the Mainstream, 1920–1945 (Volume 4) (1992) excerpt and text search

- Shapiro, Edward S. A Time for Healing: American Jewry since World War II, (Volume 5) (1992) excerpt and text search

- Antler, Joyce., ed. Talking Back: Images of Jewish Women in American Popular Culture. 1998.

- Cohen, Naomi. Jews in Christian America: The Pursuit of Religious Equality. 1992.

- Cutler, Irving. The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb. 1995

- Diner, Hasia. The Jews of the United States, 1654 to 2000 (2004) online

- Dinnerstein, Leonard. Antisemitism in America. 1994.

- Dollinger, Marc. Quest for Inclusion: Jews and Liberalism in Modern America. 2000.

- Eisen, Arnold M. The Chosen People in America: A Study in Jewish Religious Ideology. 1983.

- Glazer, Nathan. American Judaism. 2nd ed., 1989.

- Goren, Arthur. The Politics and Public Culture of American Jews. 1999.

- Gurock, Jeffrey S. From Fluidity to Rigidity: The Religious Worlds of Conservative and Orthodox Jews in Twentieth Century America. Jean and Samuel Frankel Center for Judaic Studies, 1998.

- Hyman, Paula, and Deborah Dash Moore, eds. Jewish Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia. 1997

- Lederhendler, Eli. New York Jews and the Decline of Urban Ethnicity, 1950–1970. 2001

- Moore, Deborah Dash. To the Golden Cities: Pursuing the American Jewish Dream in Miami and L. A. 1994

- Moore, Deborah Dash. GI Jews: How World War II Changed a Generation (2006)

- Norwood, Stephen H., and Eunice G. Pollack, eds. Encyclopedia of American Jewish history (2 vol 2007), 775pp; comprehenisive coverage by experts; excerpt and text search vol 1

- Novick, Peter. The Holocaust in American Life. 1999.

- Raphael, Marc Lee. Judaism in America. Columbia U. Press, 2003. 234 pp.

- Sarna, Jonathan D. American Judaism Yale University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-300-10197-X 512pp

- Sorin, Gerald. Tradition Transformed: The Jewish Experience in America. 1997.

- Staub, Michael E. ed. The Jewish 1960s: An American Sourcebook University Press of New England, 2004; 371 pp. ISBN 1-58465-417-1 online review

- Svonkin, Stuart. Jews against Prejudice: American Jews and the Fight for Civil Liberties. 1997

- Waxman, Chaim I. "What We Don't Know about the Judaism of America's Jews." Contemporary Jewry (2002) 23: 72–95. Issn: 0147-1694 Uses survey data to map the religious beliefs of American Jews, 1973–2002.

- Wertheimer, Jack, ed. The American Synagogue: A Sanctuary Transformed. 1987.

- Whitfield, Stephen J. In Search of American Jewish Culture. 1999

See also

- National Museum of American Jewish Military History

External links

- American Jewish University

- American Jewish Historical Society

- Resources > Jewish communities > America > Northern America The Jewish History Resource Center, Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Feinstein Center. Comprehensive collection of links to Jewish American history, organizations, and issues.

- United Jewish Communities of North America. Also site of population survey statistics.

- Jews in America from the Jewish Virtual Library.

- Jewish-American Literature

- Thoughts About The Jewish People By American Thinkers

- Jewish-American History on the Web

- Jewish American Hall of Fame

- The Jewish Impact on America

- 2000-01 National Jewish Population Survey

- Moran Peled, Voting with Their Feet, Eretz Acheret Magazine

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||