Gemstone

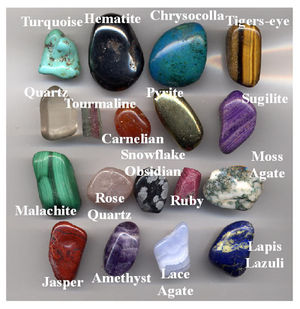

A gemstone or gem (also called a precious or semi-precious stone, or jewel) is a piece of attractive mineral, which—when cut and polished—is used to make jewelry or other adornments.[1] However certain rocks, (such as lapis lazuli) and organic materials (such as amber or jet) are not minerals, but are still used for jewelry, and are therefore often considered to be gemstones as well. Most gemstones are hard, but some soft minerals are used in jewelry because of their lustre or other physical properties that have aesthetic value. Rarity is another characteristic that lends value to a gemstone. Apart from jewelry, from earliest antiquity until the 19th century engraved gems and hardstone carvings such as cups were major luxury art forms; the carvings of Carl Fabergé were the last significant works in this tradition.

Contents |

Characteristics and classification

The traditional classification in the West, which goes back to the Ancient Greeks, begins with a distinction between precious and semi-precious stones; similar distinctions are made in other cultures. In modern usage the precious stones are diamond, ruby, sapphire and emerald, with all other gemstones being semi-precious.[2] This distinction is unscientific and reflects the rarity of the respective stones in ancient times, as well as their quality: all are translucent with fine color in their purest forms, except for the colorless diamond, and very hard,[3] with hardnesses of 8-10 on the Mohs scale. Other stones are classified by their color, translucency and hardness. The traditional distinction does not necessarily reflect modern values, for example, while garnets are relatively inexpensive, a green garnet called Tsavorite, can be far more valuable than a mid-quality emerald.[4] Another unscientific term for semi-precious gemstones used in art history and archaeology is hardstone. Use of the terms 'precious' and 'semi-precious' in a commercial context is, arguably, misleading in that it deceptively implies certain stones are intrinsically more valuable than others, which is not the case.

In modern times gemstones are identified by gemologists, who describe gems and their characteristics using technical terminology specific to the field of gemology. The first characteristic a gemologist uses to identify a gemstone is its chemical composition. For example, diamonds are made of carbon (C) and rubies of aluminium oxide (Al2O3). Next, many gems are crystals which are classified by their crystal system such as cubic or trigonal or monoclinic. Another term used is habit, the form the gem is usually found in. For example diamonds, which have a cubic crystal system, are often found as octahedrons.

Gemstones are classified into different groups, species, and varieties. For example, ruby is the red variety of the species corundum, while any other color of corundum is considered sapphire. Emerald (green), aquamarine (blue), red beryl (red), goshenite (colorless), heliodor (yellow), and morganite (pink) are all varieties of the mineral species beryl.

Gems are characterized in terms of refractive index, dispersion, specific gravity, hardness, cleavage, fracture, and luster. They may exhibit pleochroism or double refraction. They may have luminescence and a distinctive absorption spectrum.

Material or flaws within a stone may be present as inclusions.

Gemstones may also be classified in terms of their "water". This is a recognized grading of the gem's luster and/or transparency and/or "brilliance".[5] Very transparent gems are considered "first water", while "second" or "third water" gems are those of a lesser transparency.[6]

Value of gemstones

There are no universally accepted grading systems for any gemstone other than white (colorless) diamond. Diamonds are graded using a system developed by the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) in the early 1950s. Historically all gemstones were graded using the naked eye. The GIA system included a major innovation, the introduction of 10x magnification as the standard for grading clarity. Other gemstones are still graded using the naked eye (assuming 20/20 vision).[7]

A mnemonic device, the "four C's" (color, cut, clarity and carat), has been introduced to help the consumer understand the factors used to grade a diamond.[8] With modification these categories can be useful in understanding the grading of all gemstones. The four criteria carry different weight depending upon whether they are applied to colored gemstones or to colorless diamond. In diamonds, cut is the primary determinant of value followed by clarity and color. Diamonds are meant to sparkle, to break down light into its constituent rainbow colors (dispersion) chop it up into bright little pieces (scintillation) and deliver it to the eye (brilliance). In its rough crystalline form, a diamond will do none of these things, it requires proper fashioning and this is called "cut". In gemstones that have color, including colored diamonds, it is the purity and beauty of that color that is the primary determinant of quality.

Physical characteristics that make a colored stone valuable are color, clarity to a lesser extent (emeralds will always have a number of inclusions), cut, unusual optical phenomena within the stone such as color zoning, and asteria (star effects). The Greeks for example greatly valued asteria in gemstones, which were regarded as a powerful love charm, and Helen of Troy was known to have worn star-corundum.[9]

Historically gemstones were classified into precious stones and semi-precious stones. Because such a definition can change over time and vary with culture, it has always been a difficult matter to determine what constitutes precious stones.[10]

Aside from the diamond, the ruby, sapphire, emerald, pearl (strictly speaking not a gemstone) and opal[10] have also been considered to be precious. Up to the discoveries of bulk amethyst in Brazil in the 19th century, amethyst was considered a precious stone as well, going back to ancient Greece. Even in the last century certain stones such as aquamarine, peridot and cat's eye have been popular and hence been regarded as precious.

Nowadays such a distinction is no longer made by the trade.[11] Many gemstones are used in even the most expensive jewelry, depending on the brand name of the designer, fashion trends, market supply, treatments etc. Nevertheless, diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds still have a reputation that exceeds those of other gemstones.

Rare or unusual gemstones, generally meant to include those gemstones which occur so infrequently in gem quality that they are scarcely known except to connoisseurs, include andalusite, axinite, cassiterite, clinohumite and red beryl.

Gem prices can fluctuate heavily (such as those of tanzanite over the years) or can be quite stable (such as those of diamonds). In general per carat prices of larger stones are higher than those of smaller stones, but popularity of certain sizes of stone can affect prices. Typically prices can range from 1USD/carat for a normal amethyst to 20,000-50,000USD for a collector's three carat pigeon-blood almost "perfect" ruby.

Grading

In the last two decades there has been a proliferation of certification for gemstones. There are a number of[11] laboratories which grade and provide reports on diamonds. As there is no universally accepted grading system for colored gemstones, only one laboratory, AGL (see below) grades gemstones for quality using a proprietary system developed by the lab.

- International Gemological Institute (IGI), independent laboratory for grading and evaluation of diamonds, jewellery and colored stones.

- Gemological Institute of America (GIA), the main provider of education services and diamond grading reports

- Hoge Raad voor Diamant (HRD Antwerp), The Diamond High Council, Belgium is one of Europe's oldest laboratories. It's main stakeholder is the Antwerp World Diamond Centre.

- American Gemological Society (AGS) is not as widely recognized nor as old as the GIA.

- American Gem Trade Laboratory which is part of the American Gem Trade Association (AGTA) a trade organization of jewelers and dealers of colored stones.

- American Gemological Laboratories (AGL) which was sold by "Collector's Universe" a NASDAQ listed company which specializes in certification of collectables such as coins and stamps. It is now owned by Christopher P. Smith, who was awarded the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology in 2009

- European Gemological Laboratory (EGL) founded in 1974 by Guy Margel in Belgium.

- Gemmological Association of All Japan (GAAJ-ZENHOKYO), Zenhokyo, Japan, active in gemological research

- Gemmological Institute of Thailand (GIT) is closely related to Chulalongkorn University

- Gemmology Institute of Southern Africa, Africa's premium gem laboratory.

- Asian Institute of Gemmological Sciences (AIGS), the oldest gemological institute in South East Asia, involved in gemological education and gem testing

- Swiss Gemmological Institute (SSEF), founded by Prof. Henry Hänni, focusing on colored gemstones and the identification of natural pearls

- Gübelin Gem Lab, the traditional Swiss lab founded by the famous Dr. Eduard Gübelin. Their reports are widely considered as the ultimate judgement on high-end pearls, colored gemstones and diamonds

Each laboratory has its own methodology to evaluate gemstones. Consequently a stone can be called "pink" by one lab while another lab calls it "Padparadscha". One lab can conclude a stone is untreated, while another lab concludes that it is heat treated.[11] To minimise such differences, seven of the most respected labs, i.e. AGTA-GTL (New York), CISGEM (Milano), GAAJ-ZENHOKYO (Tokyo), GIA (Carlsbad), GIT (Bangkok), Gübelin (Lucerne) and SSEF (Basel), have established the Laboratory Manual Harmonisation Committee (LMHC), aiming at the standardization of wording on reports and certain analytical methods and interpretation of results. Country of origin has sometimes been difficult to find agreement on due to the constant discovery of new locations. Moreover determining a "country of origin" is much more difficult than determining other aspects of a gem (such as cut, clarity etc.).[12]

Gem dealers are aware of the differences between gem laboratories and will make use of the discrepancies to obtain the best possible certificate.[11]

Cutting and polishing

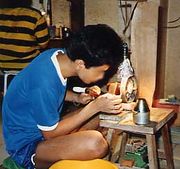

A few gemstones are used as gems in the crystal or other form in which they are found. Most however, are cut and polished for usage as jewelry. The picture to the left is of a rural, commercial cutting operation in Thailand. This small factory cuts thousands of carats of sapphire annually. The two main classifications are stones cut as smooth, dome shaped stones called cabochons, and stones which are cut with a faceting machine by polishing small flat windows called facets at regular intervals at exact angles.

Stones which are opaque such as opal, turquoise, variscite, etc. are commonly cut as cabochons. These gems are designed to show the stone's color or surface properties as in opal and star sapphires. Grinding wheels and polishing agents are used to grind, shape and polish the smooth dome shape of the stones.[13]

Gems which are transparent are normally faceted, a method which shows the optical properties of the stone’s interior to its best advantage by maximizing reflected light which is perceived by the viewer as sparkle. There are many commonly used shapes for faceted stones. The facets must be cut at the proper angles, which varies depending on the optical properties of the gem. If the angles are too steep or too shallow, the light will pass through and not be reflected back toward the viewer. The faceting machine is used to hold the stone onto a flat lap for cutting and polishing the flat facets.[14] Rarely, some cutters use special curved laps to cut and polish curved facets.

Gemstone color

Color is the most obvious and attractive feature of gemstones. The color of any material is due to the nature of light itself. Daylight, often called white light, is actually a mixture of different colors of light. When light passes through a material, some of the light may be absorbed, while the rest passes through. The part that is not absorbed reaches the eye as white light minus the absorbed colors. A ruby appears red because it absorbs all the other colors of white light (blue, yellow, green, etc.) except red.

The same material can exhibit different colors. For example ruby and sapphire have the same chemical composition (both are corundum) but exhibit different colors. Even the same gemstone can occur in many different colors: sapphires show different shades of blue and pink and "fancy sapphires" exhibit a whole range of other colors from yellow to orange-pink, the latter called "Padparadscha sapphire".

This difference in color is based on the atomic structure of the stone. Although the different stones formally have the same chemical composition, they are not exactly the same. Every now and then an atom is replaced by a completely different atom (and this could be as few as one in a million atoms). These so called impurities are sufficient to absorb certain colors and leave the other colors unaffected.

For example, beryl, which is colorless in its pure mineral form, becomes emerald with chromium impurities. If you add manganese instead of chromium, beryl becomes pink morganite. With iron, it becomes aquamarine.

Some gemstone treatments make use of the fact that these impurities can be "manipulated", thus changing the color of the gem.

Treatments applied to gemstones

Gemstones are often treated to enhance the color or clarity of the stone. Depending on the type and extent of treatment, they can affect the value of the stone. Some treatments are used widely because the resulting gem is stable, while others are not accepted most commonly because the gem color is unstable and may revert to the original tone.[15]

Heat

Heat can improve gemstone color or clarity. The heating process has been well known to gem miners and cutters for centuries, and in many stone types heating is a common practice. Most citrine is made by heating amethyst, and partial heating with a strong gradient results in ametrine - a stone partly amethyst and partly citrine. Much aquamarine is heated to remove yellow tones and change the green color into the more desirable blue or enhance its existing blue color to a purer blue.[16]

Nearly all tanzanite is heated at low temperatures to remove brown undertones and give a more desirable blue/purple color. A considerable portion of all sapphire and ruby is treated with a variety of heat treatments to improve both color and clarity.

When jewelry containing diamonds is heated (for repairs) the diamond should be protected with boracic acid; otherwise the diamond (which is pure carbon) could be burned on the surface or even burned completely up. When jewelry containing sapphires or rubies is heated, it should not be coated with boracic acid or any other substance, as this can etch the surface; they do not have to be "protected" like a diamond.

Radiation

Virtually all blue topaz, both the lighter and the darker blue shades such as "London" blue, has been irradiated to change the color from white to blue. Most greened quartz (Oro Verde) is also irradiated to achieve the yellow-green color.

Waxing/oiling

Emeralds containing natural fissures are sometimes filled with wax or oil to disguise them. This wax or oil is also colored to make the emerald appear of better color as well as clarity. Turquoise is also commonly treated in a similar manner.

Fracture filling

Fracture filling has been in use with different gemstones such as diamonds, emeralds and sapphires. In 2006 "glass filled rubies" received publicity. Rubies over 10 carat (2 g) with large fractures were filled with lead glass, thus dramatically improving the appearance (of larger rubies in particular). Such treatments are fairly easy to detect.

Synthetic and artificial gemstones

Some gemstones are manufactured to imitate other gemstones. For example, cubic zirconia is a synthetic diamond simulant composed of zirconium oxide. Moissanite is another example. The imitations copy the look and color of the real stone but possess neither their chemical nor physical characteristics. Moissanite actually has a higher refractive index than diamond and when presented beside an equivalently sized and cut diamond will have more "fire" than the diamond.

However, lab created gemstones are not imitations. For example, diamonds, ruby, sapphires and emeralds have been manufactured in labs to possess identical chemical and physical characteristics to the naturally occurring variety. Synthetic (lab created) corundums, including ruby and sapphire, are very common and they cost only a fraction of the natural stones. Smaller synthetic diamonds have been manufactured in large quantities as industrial abrasives.

Whether a gemstone is a natural stone or a lab-created (synthetic) stone, the characteristics of each are the same. Lab-created stones tend to have a more vivid color to them, as impurities are not present in a lab, so therefore do not affect the clarity or color of the stone.

Hybrid gemstones

The terms synthetic, natural, artificial, and imitation are well-understood by gemologists. However, gemologists have had to continually explain these terms, as applied in gemology, both to those within and outside of the industry, as synthetic in particular has different definitions when applied to different fields.

It is precisely because certain new gem treatments overlap more than one gem category that the term hybrid has been suggested. These materials consist of an original natural material that has been significantly added to – to the extent that the term natural no longer applies. Hybrid gems consist of natural material along with artificial material – either synthetic growth or polymers or glasses.

Hybrid is defined as those gem materials where there is no easy means of separating the natural from the artificial components. This is key, in that with a doublet or a triplet, the natural material can be isolated, identified – and theoretically retrieved from the whole. Hybrid will not be confused with assembled, but it will encompass reconstructed materials as well as B-jades.

Hybrid will not apply to traditional oiling of emerald and (comparatively minor) fracture healing as seen in many Mong Hsu rubies; these treatments are insignificant in comparison and additives would account for less than 5% of the total mass in most cases, but there remains the possibility that some heavily treated stones in these categories may qualify as hybrids.

Major industry educators, dealers, and trade organizations have seen the need for this new upper-level category. In some ways it is a dramatic addition to the gemological terms, but is merely a natural evolution due to modern treatment methods.

Notes

- ↑ The Oxford Dictionary Online and Webster Online Dictionary

- ↑ Precious Stones, Max Bauer, p 2

- ↑ Precious Gemstone glossary of Jewelry

- ↑ Wise, R. W., 2006, Secrets Of The Gem Trade, The Connoisseur's Guide To Precious Gemstones, Brunswick House Pr, pp.3-8 ISBN 0972822380

- ↑ AskOxford.com Concise Oxford English dictionary online.

- ↑ Desirable diamonds: The world's most famous gem. by Sarah Todd.

- ↑ Wise, R. W., 2006, Secrets of The Gem Trade, The Connoisseur's Guide To Precious Gemstones, Brunswick House Pr, p.36 ISBN 0972822380

- ↑ Wise, R. W., 2006, Secrets Of The Gem Trade, The Connoisseur's Guide To Precious Gemstones, Brunswick House Pr, p. 15

- ↑ Burnham, S.M. (1868). Precious Stones in Nature, Art and Literature. Bradlee Whidden. Page 251

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Church, A.H. (Professor at Royal Academy of Arts in London) (1905). Precious Stones considered in their scientific and artistic relations. His Majesty's Stationary Office, Wyman & Sons. Chapter 1, Page 9: Definition of Precious Stones URL: Definition of Precious Stones

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Secrets of the Gem Trade; The Connoisseur's Guide to Precious Gemstones Richard W Wise, Brunswick House Press, Lenox, Massachutes., 2003

- ↑ "Rapaport report of ICA Gemstone Conferene in Dubai". Diamonds.net. 2007-05-16. http://www.diamonds.net/news/NewsItem.aspx?ArticleID=17766. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ↑ Introduction to Lapidary by Pansy D. Kraus

- ↑ Faceting For Amateurs by Glen and Martha Vargas

- ↑ Gemstone Enhancement: History, Science and State of the Art by Kurt Nassau

- ↑ Nassau, Kurt (1994). Gem Enhancements. Butterworth Heineman.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||