Janissary

| Janissary New Soldier |

|

|---|---|

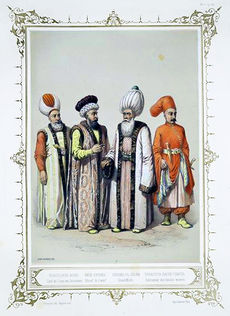

A Janissary commander confers with the Şeyhülislam of the mid-19th century Ottoman Empire (center) |

|

| Active | c. 1365–1828 |

| Allegiance | Ottoman Caliph |

| Type | Islamic |

| Size | 54,222 members during 1680, |

| Headquarters | Istanbul |

| Nickname | Order of the Temple |

| Patron | Hajji Bektash Wali |

| Motto | [Door Slaves] |

| March | Ceddin deden |

| Engagements | The Battle of Mohacs, Fall of Constantinople, Battle of Adrianople (1365), Battle of Kosovo, Battle of Varna and many others. |

| Commanders | |

| Last | Mahmud II |

|

|||||||||||||

The Janissaries (from Ottoman Turkish يکيچرى Yeniçeri meaning "new soldier") comprised infantry units that formed the Ottoman sultan's household troops and bodyguards. The force was created by the Sultan Murad I from Christian male children levied through the devşirme system from conquered countries in the 14th century[1] and was abolished by Sultan Mahmud II in 1826 with the Auspicious Incident.[2]

Contents |

Origins

The origins of the Janissaries are shrouded in myth though traditional accounts credit Orhan I – an early Ottoman bey, who reigned from 1326 to 1359 – as the founder. [3] Modern historians, such as Patrick Kinross, put the date slightly later, around 1365, under Orhan's son, Murad I, the first sultan of the Ottoman Empire.[1] The Janissaries became the first Ottoman standing army, replacing forces that mostly comprised tribal warriors (ghazis) whose loyalty and morale was not always guaranteed.[1]

From Murad I to 1648, the Janissaries were gathered through the devşirme system. This was the conscription of non-Turkish children, notably Balkan Christians and Albanian or Bosnian Muslims; Jews were never subject to devşirme, nor were children from Turkic and Armenian families up until the 17th century.

The Janissaries were kapıkulları (sing. kapıkulu), "door servants", neither free men nor ordinary slaves (Turkish: köle)[4]. They were subject to strict discipline, but they were paid salaries and pensions on retirement, and were free to marry; those conscripted through devşirme formed a distinctive social class [5] which quickly became the ruling class of the Ottoman Empire, displacing the Turkish aristocracy one of the four royal institutions: the Palace, the Scribes, the Religious and the Military. The brightest of the Janissaries were sent to the Palace institution (Enderun), where the possibility of a glittering career beckoned, perhaps even becoming grand vizier, the Sultan's powerful chief minister and military deputy.

According to military historian Michael Antonucci, not a single Janissary had been born a Muslim. Instead, every five years, Turkish administrators would scour their regions for the strongest sons of the sultan's Christian subjects. These boys, usually between the ages of 10 and 12, were then forcibly taken from their parents and enrolled in Janissary training. The recruit was immediately indoctrinated into the ways of Islam. He was supervised 24 hours a day and subjected to severe discipline. He was prohibited from growing a beard, taking up a skill other than war, or marrying. The Janissaries were extremely well-disciplined (a rarity in the Middle Ages). Perhaps the most famous Janissary was Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg, son of a despot in northern Albania. His companions gave him the nickname of Iskander Bey - "Lord Alexander" - after Alexander the Great. Not completely broken to Islam, Iskander Bey deserted the Janissaries along with 600 partisans and returned to Albania. He immediately seized the city of Kruja and destroyed its Turkish garrison. In less than a month, "Scanderbeg" (as the Europeans pronounced it) was master of Albania. Between 1443 and 1468, Scanderbeg defeated five separate Turkish armies. During the siege of Constantinople, Mehmet II sent a huge force into Albania simply to keep Scanderbeg from attempting to relieve the city. In 1468, George Castriot Scanderbeg died -- the legend is that the Janissaries gathered up his bones and wore them as amulets. [6]

Greek Historian Dimitri Kitsikis in his book, Türk Yunan İmparatorluğu ("Turco-Greek Empire")[7]states that many Christian families were willing to comply with devşirme because of the possibility of great social advancement it offered. Conscripts could one day become Janissary colonels; statesmen who might one day return to their motherland as governor; or even grand vizier or beylerbeyi (governor general), with a seat in the divan (imperial council). A famous grand vizier, was former Janissary, Sokollu Mehmed Pasha. Born in Bosnia, he served three sultans and was de facto ruler of the Ottoman Empire[8] for more than 14 years.

The Ukrainian and Serbian languages, which were in close contact with the Ottoman Empire for centuries, adopted the word, changing the pronunciation to yanichar. Cossacks and Serbs used it to refer to any warrior who converted from Christianity to Islam. In Bulgarian the word was pronounced 'enichar' with the same meaning, and the Janissaries were regarded as some of the most fearsome warriors of the Ottomans.

Janissary characteristics

The Janissary corps were distinctive in a number of ways: they wore uniforms; were paid regular salaries for their service; and marched to music, the mehter.

The Ottoman Empire was the first state to maintain a standing army in Europe since the Roman Empire. The Janissaries have been likened to the Roman Praetorian Guard and they had no equivalent in the Christian armies of the time, where the feudal lords raised troops during wartime.[1] A Janissary battalion was a close-knit community, effectively the soldier's family. They lived in barracks, serving as policemen and firefighters during peacetime.[9]

In a sharp departure from the contemporary practice of paying armies only during wartime, the Janissaries received regular salaries, paid quarterly. (By tradition, the Sultan himself, after authorizing the payments, visited the barracks dressed as a Janissary trooper, and received his pay alongside the other men of the First Division.)[10]

The Janissaries also enjoyed far better support on campaign than their contemporaries. They were part of a well-organized military machine, with one support corps preparing the road and others pitching tents at night and baking the bread. Their weapons and ammunition were transported and re-supplied by the cebeci corps. They campaigned with their own medical teams of Muslim and Jewish surgeons; their sick and wounded were evacuated to dedicated mobile hospitals set up behind the lines.[10]

These differences, along with a war-record that was impressive, made the Janissaries into a subject of interest and study by foreigners in their own time. Although eventually the concept of the modern army incorporated and surpassed most of the distinctions of the Janissary, and the Ottoman Empire dissolved the Janissary corps, the image of the Janissary has remained as one of the symbols of the Ottomans in the western psyche.

In return for their loyalty and their fervour in war, Janissaries gained privileges and benefits. They received a cash salary, received booty during wartime and enjoyed a high living standard and respected social status. At first they had to live in barracks and could not marry until retirement, or engage in any other trade, but by the mid-18th century they had taken up many trades and gained the right to marry and enroll their children in the corps and very few continued to live in the barracks.[9] Many of them became administrators and scholars. Retired or discharged Janissaries received pensions and their children were also looked after. This evolution away from their original military vocation was the major cause of the system's demise.

Recruitment, training and status

The first Janissary units were formed from prisoners of war and slaves, probably as a result of the sultan taking his traditional one-fifth share of his army's booty in kind rather than cash.[3] From the 1380s onwards, their ranks were filled under the devşirme system, where feudal dues were paid by service to the sultan.[3] The "recruits" were mostly Christian youths, reminiscent of Mamelukes.[1] Sultan Murad may have used futuwa groups as a model.

Initially the recruiters favoured Greeks (who formed the largest part of the first units) and Albanians (who also served as gendarmes), usually selecting about one boy from forty houses, but the numbers could be changed to correspond with the need for soldiers. Boys aged 14-18 were preferred, though ages 8-20 could be taken."[11]

As borders of the Ottoman Empire expanded, the devşirme was extended to include Bulgarians, Croats, Bosnians, Serbs and later Romanians, Georgians, Poles, Ukrainians and southern Russians.

The Janissaries first began enrolling outside the devşirme system during the reign of Sultan Murad III (1546-1595) and abandoned devşirme recruitment completely during the 17th century. After this period, volunteers were enrolled, mostly of Muslim origin.[10]

The Janissaries’ reputation increased to the point that by 1683, Sultan Mehmet IV abolished the devşirme, as increasing numbers of originally Muslim Turkish families had already enrolled their own sons into the force hoping for a lucrative career. Every governor wanted to have his own Janissary troops.

Training

Janissaries trained under strict discipline with hard labour and in practically monastic conditions in acemi oğlan ("rookie" or "cadet") schools, where they were expected to remain celibate. They were also expected to convert to Islam. All did, as Christians were not allowed to bear arms in the Ottoman Empire until the 19th century. Unlike other Muslims, they were expressly forbidden to wear beards, only a moustache. These rules were obeyed by Janissaries, at least until the 18th century when they also began to engage in other crafts and trades, breaking another of the original rules.

For all practical purposes, Janissaries belonged to the Sultan, carrying the title kapıkulu ("door subjects") they were regarded as the protectors of the throne and the Sultan. Janissaries were taught to consider the corps as their home and family, and the Sultan as their father. Only those who proved strong enough earned the rank of true Janissary at the age of twenty-four or twenty-five. The Ocak inherited the property of dead Janissaries, thus amassing wealth (like religious orders and foundations enjoying the "dead hand").

Janissaries also learned to follow the dictates of the dervish saint Hajji Bektash Wali, disciples of whom had blessed the first troops. Bektashi served as a kind of chaplain for Janissaries. In this and in their secluded life, Janissaries resembled Christian military orders like the Johannites of Rhodes.

Janissary corps

The corps was organized in ortas (equivalent to battalion). An orta was headed by çorbaci. All ortas together would comprise the proper Janissary corps and its organization named ocak (literally "hearth"). Suleiman I had 165 ortas but the number over time increased to 196. The Sultan was the supreme commander of the Army and the Janissaries in particular, but the corps was organized and led by their supreme ağa (commander). The corps was divided into three sub-corps:

- the cemaat (frontier troops; also spelled jemaat), with 101 ortas

- the beyliks or beuluks (the Sultan's own bodyguard), with 61 ortas

- the sekban or seirnen, with 34 ortas

In addition there were also 34 ortas of the ajemi (cadets). A semi-autonomous Janissary corps permanently based in Algiers.

Originally Janissaries could be promoted only through seniority and within their own orta. They would leave the unit only to assume command of another. Only Janissaries' own commanding officers could punish them. The rank names were based on positions in a kitchen staff or troop of hunters, perhaps to emphasise that Janissaries were servants of the Sultan.

Local Janissaries, stationed in a town or city for a long time, were known as yerliyyas.

Corps strength

| Year | Strength |

|---|---|

| 1400 | >1,000[12] |

| 1514 | 10,156 [13] |

| 1523 | 12,000[13] |

| 1526 | 7,885[13] |

| 1564 | 13,502[13] |

| 1567-68 | 12,798[13] |

| 1574 | 13,599[13] |

| 1603 | 14,000[13] |

| 1609 | 37,627[13] |

| 1660-61 | 54,222[13] |

| 1665 | 49,556[13] |

| 1669 | 51,437[13] |

| 1670 | 49,868[13] |

| 1680 | 54,222[13] |

The full strength of the Janissary troops varied from maybe 100 to more than 200,000. According to David Nicolle, the number of Janissaries in the 14th century was 1,000, and estimated to be 6,000 in 1475, whereas the same source estimates 40,000 as the number of Timariot, the provincial soldiers.[12] After the defeat in 1699, the number was reduced, but it was increased in the 18th century to 113,400 soldiers according to Ottoman, but most were not actual soldiers and were accepted into the army through corrupt means and were only taking salary.[12]

Equipment

In the first centuries, Janissaries were expert archers, but they began adopting firearms as soon as such became available during the 1440s. The siege of Vienna in 1529 confirmed the reputation of their engineers, e.g. sapping and mining. In melee combat they used axes and sabres. Originally in peacetime they could carry only clubs or cutlasses, unless they served as border troops.

By the early 16th century, the Janissaries were equipped with and were skilled with muskets.[14] In particular, they used a massive 'trench gun', firing an 80-millimetre (3.1 in) ball, which was "feared by their enemies".[14] Janissaries also made extensive use of early grenades and hand cannon, such as the abus gun.[10] Pistols were not initially popular but they became so after the Cretan War (1645–1669).[15]

Battles

The Ottoman empire used Janissaries in all its major campaigns, including the 1453 capture of Constantinople, the defeat of the Egyptian Mamluks and wars against Hungary and Austria. Janissary troops were always led to the battle by the Sultan himself, and always had a share of the booty.

Revolts and disbandment

As Janissaries became aware of their own importance they began to desire a better life. By the early 17th century Janissaries had such prestige and influence that they dominated the government. They could mutiny and dictate policy and hinder efforts to modernize the army structure. They could change Sultans as they wished through palace coups. They made themselves landholders and tradesmen. They would also limit the enlistment to the sons of former Janissaries who did not have to go through the original training period in the acemi oğlan, as well as avoiding the physical selection, thereby reducing their military value.

When Janissaries could practically extort money from the Sultan and business and family life replaced martial fervour, their effectiveness as combat troops decreased. The northern borders of the Ottoman Empire slowly began to shrink southwards after the second Battle of Vienna in 1683.

In 1449 they revolted for the first time, demanding higher wages, which they obtained. The stage was set for a decadent evolution, like the Streltsy of Tsar Peter's Russia or Praetorian Guard which had proved the greatest threat to Roman emperors, rather than an effective protection. After 1451, every new Sultan felt obligated to pay each Janissary a reward and raise his pay rank. Sultan Selim II gave janissaries permission to marry in 1566, undermining the exclusivity of loyalty to the dynasty.

By 1622, the Janissaries were a "serious threat" to the stability of the Empire.[16] Through their "greed and indiscipline", they were now a law unto themselves and, against modern European armies, ineffective on the battlefield as a fighting force. [16] In 1622, the teenage sultan, Osman II, after a defeat during war against Poland determined to curb Janissary excesses and outraged at becoming "subject to his own slaves" tried to disband the Janissary corps blaming it for the disaster during Polish war.[16] In the spring, hearing rumours that the Sultan was preparing to move against them, the Janissaries revolted and took the Sultan captive, imprisoning him in the notorious Seven Towers: he was murdered shortly afterwards.[16]

In 1807 a Janissary revolt deposed Sultan Selim III, who had tried to modernize the army along Western European lines.[17] His supporters failed to recapture power before Mustafa IV had him killed, but elevated Mahmud II to the throne in 1808.[17] When the Janissaries threatened to oust Mahmud II, he had the captured Mustafa executed and eventually came to a compromise with the Janissaries.[17] Ever mindful of the Janissary threat, the sultan spent the next years discreetly securing his position. The Janissaries' abuse of power, military ineffectiveness, resistance to reform and the cost of salaries to 135,000 men, many of whom were not actually serving soldiers, had all become intolerable[18].

By 1826, the sultan was ready to move. Historian Patrick Kinross suggests that Mahmud II incited them to revolt on purpose, describing it as the sultan's "coup against the Janissaries".[2] The sultan informed them, though a fatwa, that he was forming a new army, organised and trained along modern European lines.[2] As predicted, they mutinied, advancing on the sultan's palace.[2] In the ensuing fight, the Janissary barracks were set in flames by artillery fire resulting in 4,000 Janissary fatalities.[2] The survivors were either exiled or executed, and their possessions were confiscated by the Sultan.[2] This event is now called the Auspicious Incident. The last of the Janissaries were then put to death by decapitation in what was later called the blood tower, in Thessaloniki.

Janissary music

In modern times, although the Janissary corps no longer exists as a professional fighting force, the tradition of Mehter music is carried on as a cultural and tourist attraction.

The military march music of the Janissaries is characteristic because of its powerful, often shrill sound combining davul (bass drum), zurna (a loud oboe), naffir (trumpet), bells, triangle, and cymbals (zil), among others. Janissary music influenced European classical musicians like Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Ludwig van Beethoven, both of whom composed marches in the Turkish style (Mozart's Piano Sonata in A major, K. 331 (c. 1783), and Beethoven's incidental music for The Ruins of Athens, Op. 113 (1811), and the final movement of Symphony no. 9).

In 1952, the Janissary military band, Mehterân, was organized again under the auspices of the Istanbul Military Museum. They have performances during some national holidays as well as in some parades during days of historical importance. For more details, see Turkish music (style) and Mehter.

See also

- Culture of the Ottoman Empire

- Devşirme system

- Ghilman

- Mamluk

- Millet system

- Military of the Ottoman Empire

- Saqaliba

Notes and sources

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Kinross, pp 48–52.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Kinross, pp. 456–457.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Nicolle, p. 7.

- ↑ Shaw, Stanford; Ezel Kural Shaw (1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, Volume I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 0521212804.

- ↑ Zürcher, Erik (1999). Arming the State. United States of America: LB Tauris and Co Ltd. pp. 5. ISBN 186064404X.

- ↑ Antonucci, Michael. "The Sultan's Christian-Born Fighters". Military History. 1992.

- ↑ Kitsikis, Dimitri (1996). Türk Yunan İmparatorluğu. Istanbul,Simurg Kitabevi

- ↑ Imamović, Mustafa (1996). Historija Bošnjaka. Sarajevo: BZK Preporod. ISBN 9958-815-00-1

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Goodwin. J, pp. 59, 179-181

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Uzunçarşılı, pp 66-67, 376-377, 405-406, 411-463, 482-483

- ↑ Kitsikis, Dimitri (1996). Türk Yunan İmparatorluğu. Istanbul,Simurg Kitabevi

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Nicolle, pp 9–10.

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 13.11 13.12 Agoston, p. 50

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Nicolle, p.36.

- ↑ Nicolle, pp 21–22.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Kinross, pp 292–295

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Kinross, pp 431–434.

- ↑ Levy, Avigdor. "The Ottoman Ulama and the Military Reforms of Sultan Mahmud II." Asian and African Studies 7 (1971): 13 - 39.

Sources

- Agoston, Gabor. Barut, Top ve Tüfek Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun Asker Gücü ve Silah Sanayisi, ISBN 975-6051-41-8.

- Goodwin, Godfrey (2001). The Janissaries. UK: Saqi Books. ISBN 9780863560552

- Goodwin, Jason (1998). Lords of the Horizons: A History of the Ottoman Empire. New York: H. Holt ISBN 0-8050-4081-1

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans, 18th and 19th Centuries. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521 27458-3

- Kinross, Patrick (1977). The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire London: Perennial. ISBN 9780688080938

- Nicolle, David (1995). The Janissaries. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781855324138

- Shaw, Stanford J. (1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey (Vol. I). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521291637

- Shaw, Stanford J. & Shaw, Ezel Kural (1977). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey (Vol. II). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521291668

- Uzunçarşılı, İsmail (1988). Osmanlı Devleti Teşkilatından Kapıkulu Ocakları: Acemi Ocağı ve Yeniçeri Ocağı. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu. ISBN 975-16-0056-1

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.