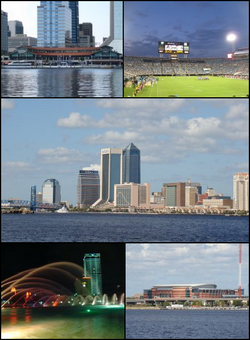

Jacksonville, Florida

| City of Jacksonville, Florida | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| — Consolidated city–county — | |||

|

|||

|

|||

| Nickname(s): The River City, Jax, J-ville | |||

| Motto: Where Florida Begins | |||

|

|||

City of Jacksonville, Florida

|

|||

| Coordinates: | |||

| Country | |||

| State | |||

| County | Duval | ||

| Founded | 1791 | ||

| Incorporated | 1832 | ||

| Government | |||

| - Type | Mayor-Council | ||

| - Mayor | John Peyton (R) | ||

| - Governing body | Jacksonville City Council | ||

| Area | |||

| - Consolidated city–county | 885 sq mi (2,292.15 km2) | ||

| - Land | 767 sq mi (1,986.53 km2) | ||

| - Water | 116.6 sq mi (302.1 km2) | ||

| Elevation | 16 ft (5 m) | ||

| Population (2010)[1] | |||

| - Consolidated city–county | 813,518 (13th) | ||

| - Density | 1,061.6/sq mi (409.89/km2) | ||

| - Urban | 913,125 | ||

| - Metro | 1,525,228 | ||

| Time zone | EST (UTC-5) | ||

| - Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) | ||

| ZIP code | 32099, 32201-32212, 32214-32241, 32244-32247, 32250, 32254-32260, 32266, 32267, 32277, 32290. | ||

| Area code(s) | 904 | ||

| FIPS code | 12-35000[2] | ||

| GNIS feature ID | 0295003[3] | ||

| Website | http://www.coj.net | ||

Jacksonville is the largest city in the U.S. state of Florida and the county seat of Duval County.[4] The governments of the City of Jacksonville and Duval County consolidated in 1968, giving Jacksonville a particularly large land area and placing most of its metropolitan area within the city limits. As a result it is the most populous city proper in Florida and the thirteenth most populous in the United States. Jacksonville is the principal city in the Greater Jacksonville Metropolitan Area, a region with a population of more than 1,525,228.[5]

Jacksonville is located in the First Coast region of northeast Florida and is centered on the banks of the St. Johns River, about 25 miles (40 km) south of the Georgia border and about 340 miles (547 km) north of Miami. The European-American settlement that became Jacksonville was founded in 1791 as Cowford, so named because of its location at a narrow point in the river where cattle once crossed. In 1822, a year after the United States acquired the colony of Florida from Spain, the city was renamed for Andrew Jackson, the first military governor of the Florida Territory and seventh President of the United States.

Contents |

History

The area of the modern city of Jacksonville has been inhabited for thousands of years. On Black Hammock Island in the national Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve, a University of North Florida team discovered some of the oldest remnants of pottery in the United States, dating to 2500 BC.[6] In the 16th century, the beginning of the historical era, the region was inhabited by the Mocama, a coastal subgroup of the Timucua people. At the time of contact with Europeans, most Mocama villages in present-day Jacksonville were part of the powerful chiefdom known as the Saturiwa, centered on Fort George Island near the mouth of the St. Johns River.[7] One early map shows a village called Ossachite located at the site of what is now downtown Jacksonville; this may be the earliest recorded name for the downtown Jacksonville area.[8]

European explorers first arrived in the area 1562, when French Huguenot explorer Jean Ribault charted the St. Johns River. Two years later, in 1564, René Goulaine de Laudonnière established the first European settlement at Fort Caroline, located on the St. Johns near the main village of the Saturiwa. On September 20, 1565, a Spanish force from the nearby Spanish settlement of St. Augustine attacked Fort Caroline, and killed nearly all the French soldiers defending it.[9] The Spanish renamed it Fort San Mateo. With the destruction of the French forces at Fort Caroline, St. Augustine's position as the most important settlement in Florida was solidified.

Spain ceded Florida to the British in 1763 following their victory in the Seven Years War. Britain ceded control to Spain in 1783, following defeat in the American Revolutionary War. The first permanent settlement in modern Jacksonville was settled as "Cowford" in 1791, ostensibly named for a narrow point in the St. Johns River where cattlemen could have their livestock ford the water. Spain finally ceded the Florida Territory to the United States in 1821. In 1822, United States settlers began using Jacksonville's current name. Led by Isaiah D. Hart, residents wrote a charter for a town government, which was approved by the Florida Legislative Council on February 9, 1832.

During the American Civil War, Jacksonville was a key supply point for hogs and cattle being shipped from Florida to aid the Confederate cause. The city was blockaded by Union forces, who gained control of the nearby Fort Clinch. From 1862, they controlled the city and most of the First Coast for the duration of the war. Though no battles were fought in Jacksonville, the city changed hands several times. Warfare and the long occupation left the city disrupted after the war.

During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, Jacksonville and nearby St. Augustine became popular winter resorts for the rich and famous. Visitors arrived by steamboat and later by railroad. President Grover Cleveland attended the Sub-Tropical Exposition in the city on February 22, 1888 during his trip to Florida.[10] This highlighted the visibility of the state as a worthy place for tourism.

The city's tourism, however, was dealt major blows in the late 19th century by yellow fever outbreaks. In addition, extension of the Florida East Coast Railway to south Florida drew visitors to other areas. From 1893 to 1938 Jacksonville was the site of the Florida Old Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Home with a nearby cemetery.[11]

On May 3, 1901, downtown Jacksonville was ravaged by a fire that started at a fiber factory. Known as the "Great Fire of 1901", it was one of the worst disasters in Florida history and the largest urban fire in the Southeastern United States. Over eight hours, it destroyed the business district and left 10,000 residents homeless. It is said the glow from the flames could be seen in Savannah, Georgia, and the smoke plumes in Raleigh, North Carolina. Architect Henry John Klutho was a primary figure in the reconstruction of the city. More than 13,000 buildings were constructed between 1901 and 1912.

In the 1910s, New York–based moviemakers were attracted to Jacksonville's warm climate, exotic locations, excellent rail access, and cheap labor. Over the course of the decade, more than 30 silent film studios were established, earning Jacksonville the title, "Winter Film Capital of the World". However, the city's conservative political climate and the emergence of Hollywood as a major film production center ended the city's film industry. One converted movie studio site, Norman Studios, remains in Arlington; It has been converted to the Jacksonville Silent Film Museum at Norman Studios.[12]

During this time, Jacksonville also became a banking and insurance center, with companies such as Barnett Bank, Atlantic National Bank, Florida National Bank, Prudential, Gulf Life, Afro-American Insurance, Independent Life and American Heritage Life thriving in the business district. The U.S. Navy also became a major employer and economic force during the 1940s, with the construction of three naval bases in the city.

Jacksonville, like most large cities in the United States, suffered from negative effects of rapid urban sprawl after World War II. The construction of highways led residents to move to newer housing in the suburbs.

After World War II, the government of the city of Jacksonville began to increase spending to fund new public building projects in the boom that occurred after the war. Mayor W. Haydon Burns' Jacksonville Story resulted in the construction of a new city hall, civic auditorium, public library and other projects that created a dynamic sense of civic pride. However, the development of suburbs and a subsequent wave of middle class "white flight" left Jacksonville with a much poorer population than before.

Much of the city's tax base dissipated, leading to problems with funding education, sanitation, and traffic control within the city limits. In addition, residents in unincorporated suburbs had difficulty obtaining municipal services, such as sewage and building code enforcement. In 1958, a study recommended that the city of Jacksonville begin annexing outlying communities in order to create the needed tax base to improve services throughout the county. Voters outside the city limits rejected annexation plans in six referendums between 1960 and 1965.

In the mid 1960s, corruption scandals began to arise among many of the city's officials, who were mainly elected through the traditional good ol' boy network. After a grand jury was convened to investigate, 11 officials were indicted and more were forced to resign. Consolidation, led by J. J. Daniel and Claude Yates, began to win more support during this period, from both inner city blacks, who wanted more involvement in government, and whites in the suburbs, who wanted more services and more control over the central city.In 1964 all 15 of Duval County's public high schools lost their accreditation. This added momentum to proposals for government reform. Lower taxes, increased economic development, unification of the community, better public spending and effective administration by a more central authority were all cited as reasons for a new consolidated government.

When a consolidation referendum was held in 1967, voters approved the plan. On October 1, 1968, the governments merged to create the Consolidated City of Jacksonville. Fire, police, health & welfare, recreation, public works, and housing & urban development were all combined under the new government.

The Better Jacksonville Plan, promoted as a blueprint for Jacksonville's future and approved by Jacksonville voters in 2000, authorized a half-penny sales tax. This would generate most of the revenue required for the $2.25 billion package of major projects that included road & infrastructure improvements, environmental preservation, targeted economic development and new or improved public facilities.[13]

Geography

Topography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 874.3 square miles (2,264 km2), making Jacksonville the largest city in land area in the contiguous United States; of this, 86.66% (757.7 sq mi, 1,962 km2) is land and ; 13.34% (116.7 sq mi, 302 km2) is water. Jacksonville completely encircles the town of Baldwin. Nassau County lies to the north, Baker County lies to the west, and Clay and St. Johns County lie to the south; the Atlantic Ocean lies to the east, along with the Jacksonville Beaches. The St. Johns River divides the city. The Trout River, a major tributary of the St. Johns River, is located entirely within Jacksonville.

Climate

Jacksonville has a humid subtropical climate (Koppen Cfa), with mild weather during winters and hot weather during summers. High temperatures average 64 to 91 °F (18 to 33 °C) throughout the year.[14] High heat indices are not uncommon for the summer months in the Jacksonville area. High temperatures can reach the mid and upper 90s with heat indices above 110 °F (43.3 °C) possible. The highest temperature ever recorded in Jacksonville was 105 °F (41 °C) on July 21, 1942. It is common for thunderstorms to erupt during a typical summer afternoon. These are caused by the rapid heating of the land relative to the water, combined with extremely high humidity.

During winter, there can be hard freezes during the night. Such cold weather is usually short lived, as the city averages only 10 to 15 nights below freezing.[15] The coldest temperature recorded at Jacksonville International Airport was 7 °F (−13.9 °C) on January 21, 1985, a day that still holds the record cold for many locations in the eastern half of the US. Even rarer in Jacksonville than freezing temperatures is snow. When snow does fall, it usually melts upon making contact with the ground. Most residents of Jacksonville can remember accumulated snow on only one occasion—-a thin ground cover that occurred December 23 of 1989.[16]

Jacksonville has suffered less damage from hurricanes than most other east coast cities, although the threat does exist for a direct hit by a major hurricane. The city has only received one direct hit from a hurricane since 1871, although Jacksonville has experienced hurricane or near-hurricane conditions more than a dozen times due to storms passing through the state from the Gulf of Mexico to the Atlantic Ocean, or passing to the north or south in the Atlantic and brushing past the area.[17] The strongest effect on Jacksonville was from Hurricane Dora in 1964, the only recorded storm to hit the First Coast with sustained hurricane force winds. The eye crossed St. Augustine with winds that had just barely diminished to 110 mph (180 km/h), making it a strong Category 2 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale. Jacksonville also suffered damage from 2008's Tropical Storm Fay which crisscrossed the state, bringing parts of Jacksonville under darkness for four days. Similarly, four years prior to this, Jacksonville was inundated by Hurricane Frances and Hurricane Jeanne, which made landfall south of the area. These tropical cyclones were the costliest indirect hits to Jacksonville. Hurricane Floyd in 1999 caused damage mainly to Jacksonville Beach. During Floyd, the Jacksonville Beach pier was completely destroyed. The rebuilt pier was later heavily damaged by Fay, but not destroyed.

Rainfall averages around 52 inches (1,300 mm) a year, with the wettest months being June through September.

| Climate data for Jacksonville, Florida (Jacksonville Beach) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 85 (29.4) |

90 (32.2) |

94 (34.4) |

94 (34.4) |

97 (36.1) |

102 (38.9) |

103 (39.4) |

102 (38.9) |

98 (36.7) |

95 (35) |

89 (31.7) |

85 (29.4) |

103 (39.4) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 63.5 (17.5) |

64.7 (18.17) |

70.0 (21.11) |

75.8 (24.33) |

81.8 (27.67) |

86.7 (30.39) |

89.3 (31.83) |

88.0 (31.11) |

85.2 (29.56) |

79.0 (26.11) |

71.9 (22.17) |

65.4 (18.56) |

76.8 (24.89) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 45.6 (7.56) |

47.5 (8.61) |

52.9 (11.61) |

58.7 (14.83) |

65.8 (18.78) |

71.6 (22) |

73.5 (23.06) |

73.8 (23.22) |

72.5 (22.5) |

64.9 (18.28) |

56.3 (13.5) |

48.6 (9.22) |

61.0 (16.11) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 14 (-10) |

21 (-6.1) |

24 (-4.4) |

37 (2.8) |

47 (8.3) |

55 (12.8) |

57 (13.9) |

63 (17.2) |

53 (11.7) |

38 (3.3) |

25 (-3.9) |

15 (-9.4) |

14 (-10) |

| Rainfall inches (mm) | 3.56 (90.4) |

2.84 (72.1) |

3.92 (99.6) |

2.87 (72.9) |

3.03 (77) |

5.70 (144.8) |

5.21 (132.3) |

6.11 (155.2) |

7.53 (191.3) |

5.04 (128) |

2.36 (59.9) |

2.75 (69.9) |

50.92 (1,293.4) |

| Avg. rainy days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.7 | 7.5 | 7.9 | 5.8 | 7.5 | 11.5 | 10.9 | 12.0 | 12.2 | 8.8 | 7.2 | 8.4 | 108.4 |

| Sunshine hours | 189.1 | 194.9 | 257.3 | 285.0 | 303.8 | 285.0 | 282.1 | 263.5 | 228.0 | 213.9 | 195.0 | 182.9 | 2,880.5 |

| Source: NOAA (normals, 1971-2000)[18], HKO (sun, taken at JAX) [19] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Architecture

Downtown Jacksonville has a skyline with the tallest building being the Bank of America Tower, constructed in 1990 as the Barnett Bank Center. It has a height of 617 ft (188 m) and includes 42[20][21] floors. Other notable structures include the 37-story Modis Building (with its distinctive flared base making it the defining building in the Jacksonville skyline), originally built in 1972-74 by the Independent Life and Accident Insurance Company, and the 28 floor Riverplace Tower which, when completed in 1967, was the tallest precast, post-tensioned concrete structure in the world. [22][23]

| Rank | Name | Street Address | Height feet / meters |

Floors | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bank of America Tower | 50 North Laura Street | 617 / 188 | 42[20][21] | 1990 |

| 2 | Modis Building | 1 Independent Drive | 535 / 163 | 37 | 1974 |

| 3 | AT&T Tower | 301 West Bay Street | 447 / 136 | 32 | 1983 |

| 4 | The Peninsula at St. Johns Center | 1401 Riverplace Boulevard | 437 / 133 | 36 | 2006 |

| 5 | Riverplace Tower | 1301 Riverplace Boulevard | 432 / 132 | 28 | 1967 |

Neighborhoods

As the largest city in land area in the contiguous United States, Jacksonville’s official website divides the city into six major sections:[24]

- Greater Arlington (Arlington) is situated east and south of the St. Johns River and north of Beach Blvd.

- North Jacksonville, (Northside) officially considered to be everything north of the St. Johns & Trout Rivers and east of US 1.

- Northwest Jacksonville is located north of Interstate 10, south of the Trout River.

- Southeast Jacksonville (Southside, Mandarin), referring to everything east of the St. Johns River and south of Beach Blvd.

- West Jacksonville (Westside) consists of everything west of the St. Johns River and south of Interstate 10.

- Urban Core (Downtown Jacksonville) includes the south & north banks of the narrowest part of the St. Johns River east from the Fuller Warren Bridge and extending roughly 4 miles (6.4 km) north and east.

Jacksonville is divided into several sections; Northside, Southside and Westside, with each section having several distinct neighborhoods. Additionally, four cities within Duval County retain their own municipal governments, though they are represented in the Jacksonville City Council: Baldwin, Atlantic Beach, Neptune Beach, and Jacksonville Beach. The latter three communities form part of the area known as the Jacksonville Beaches.

Today, what distinguishes a "section" of Jacksonville from a "neighborhood" is primarily a matter of size and divisibility. However, definitions are imprecise, and sometimes not universally agreed upon. Each of these sections is large and divided into many neighborhoods. Each neighborhood has its own identity. Some, such as Mandarin, LaVilla, Springfield and Bayard were independent towns or villages before the consolidation, and have their own histories.

Parks and gardens

Jacksonville operates the largest urban park system in the United States, providing facilities and services at more than 337 locations on more than 80,000 acres (320 km2) located throughout the city.[25] Jacksonville enjoys natural beauty from the St. Johns River and Atlantic Ocean. Many parks provide access for people to boat, swim, fish, sail, jetski, surf and waterski. Several parks around the city have received international recognition. Kids Kampus, in particular, is a unique facility for families with young children.

Tree Hill Nature Center is a nature preserve conveniently located five minutes from Downtown Jacksonville. Tree Hill is home to an environmental education center, a wildlife area, a Butterfly Center and 50 acres of nature trails surrounded by hilltop and wetland areas consisting of southern mixed hardwood forest, mixed hardwood swamp and freshwater streams. Serving the Jacksonville community for 40 years with important environmental education programs, Tree Hill also hosts a popular Butterfly Festival on the last Saturday of every April in the Joseph A. Strasser Amphitheater.

Hemming Plaza is Jacksonville's first and oldest park. It is downtown and surrounded by government buildings.

The Jacksonville Arboretum and Gardens broke ground on a new center in April, 2007 and held their grand opening on November 15, 2008.

The Veterans Memorial Wall is a tribute to local servicemen and women killed while serving in US armed forces. A ceremony is held each Memorial Day recognizing any service woman or man from Jacksonville who died in the previous year.

The Treaty Oak is a massive, 250 year-old tree at Jessie Ball DuPont Park in downtown. Office workers from nearby buildings sit on benches to eat lunch or read a book in the shade of its canopy.

The Jacksonville-Baldwin Rail Trail is a linear city park which runs 14.5 miles (23.3 km) from Imeson Road to a point past Baldwin, Florida.

Culture

Entertainment and performing arts

The Florida Theatre, opened in 1927, is located in downtown Jacksonville and is one of only four remaining high-style movie palaces built in Florida during the Mediterranean Revival architectural boom of the 1920s.

Amity Turkish Cultural Center was established in 2006 as one of the major Dialogue and Cultural organizations in Jacksonville. Theatre Jacksonville was organized in 1919 as the Little Theatre and is one of the oldest continually producing community theatres in the United States.

The Riverside Theater opened in 1927. It was the first theater equipped to show talking pictures in Florida and the third nationally. It is located in the Five Points section of town and was renamed the Five Points Theater in 1949.[26][27]

The Ritz Theatre, opened in 1929, is located in the LaVilla neighborhood of the northern part of Jacksonville's downtown. Rebuilt and opened in October, 1999.

The Times-Union Center for the Performing Arts consists of three distinct halls: the Jim & Jan Moran Theater, a venue for touring Broadway shows; the Jacoby Symphony Hall, home of the Jacksonville Symphony Orchestra; and the Terry Theater, intended for small shows and recitals. The building was originally erected as the Civic Auditorium in 1962 and underwent a major renovation and construction in 1996.

The Jacksonville Veterans Memorial Arena, which opened in 2003, is a 16,000-seat performance venue that attracts national entertainment, sporting events and also houses the Jacksonville Sports Hall of Fame. It replaced the outdated Jacksonville Memorial Coliseum that was built in 1960 and demolished on June 26, 2003.

The Alhambra Dinner Theatre, located on the Southside near the University of North Florida, has offered professional productions that frequently starred well-known actors since 1967. There are also a number of popular community theatres such as Players by the Sea at Jacksonville Beach.[28] Atlantic Beach Experemental Theatre (ABET),[29] and Orange Park Community Theatre.[30]

In 1999, Stage Aurora Theatrical Company, Inc. was established in collaboration at Florida State College at Jacksonville (North Campus). Their goal is to produce theatre that enlightens, and it is the most popular theatre on the Northside, located at Gateway Town Center.[31]

Jacksonville is also home to The Teal Sound Drum and Bugle Corps, a junior team that competes in Drum Corps International World Class competition.

The Mad Cowford Improv Troupe is Jacksonville's only improvisational comedy group. They perform at Northstar Substation on Friday nights and offer low-cost workshops during the week for anyone interested in the genre.

The Jacksonville music scene was active in the 1930s in LaVilla, which was known as “Harlem of the South”.[32] Black musicians from across the country visited Jacksonville to play standing room only performances at the Ritz Theatre and the Knights of Pythias Hall. Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong were a few of the legendary performers who appeared. After his mother died when he was 15, Ray Charles lived with friends of his mother while he played piano at the Ritz for a year, before moving on to fame and fortune.

Jacksonville native Pat Boone was a popular 1950s singer and teen idol. During the 1960s, the Classics Four was the most successful pop rock band from Jacksonville. Southern Rock was defined by the Allman Brothers Band, which formed in 1969 in Jacksonville. Lynyrd Skynyrd achieved near cult status and inspired Blackfoot, Molly Hatchet and .38 Special, all successful in the 1970s. The 1980s were a quiet decade for musical talent in Jacksonville. The next local group to achieve national success was nu-metal band Limp Bizkit in 1994. Other popular Hip Hop acts in the 1990s included 95 South, 69 Boyz and the Quad City DJ's. The bands Inspection 12, Cold and Yellowcard were also well known and had a large following. Following the millennium, Burn Season, Evergreen Terrace, Shinedown, Electric President, The Red Jumpsuit Apparatus, Black Kids and The Summer Obsession were notable bands from Jacksonville.

In the early 1900s, New York-based moviemakers were attracted to Jacksonville's warm climate, exotic locations, excellent rail access, and cheaper labor, earning the city the title of "The Winter Film Capital of the World". Over 30 movie studios were opened and thousands of silent films produced between 1908 and the 1920s, when most studios relocated to Hollywood, California.

Since that time, Jacksonville has been chosen by a number of film and television studios for on-location shooting. Notable motion pictures that have been partially or completely shot in Jacksonville since the silent film era include Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), The New Adventures of Pippi Longstocking (1988), Brenda Starr (1989), G.I. Jane (1997), The Devil's Advocate (1997), Ride (1998), Why Do Fools Fall In Love (1998), Forces of Nature (1999), Tigerland (2000), Sunshine State (2002), Basic (2003), The Manchurian Candidate (2004), Lonely Hearts (2006), Moving McAllister (2007), The Year of Getting to Know Us (2008).

Notable television series or made-for-television films that have been partially or completely shot in Jacksonville include Intimate Strangers (1986), Inherit the Wind (1988), Roxanne: The Prize Pulitzer (1989), A Girl of the Limberlost (1990), Orpheus Descending (1990), Pointman (1995), Saved by the Light (1995), The Babysitter's Seduction (1996), Sudden Terror: The Hijacking of School Bus #17 (1996), First Time Felon (1997), Gold Coast (1997), Safe Harbor (film) (1999), The Conquest of America (2005), Super Bowl XXXIX (2005), Recount (film) (2008), and American Idol (2009). In an episode of NCIS, the suspect/criminal was stationed at Naval Air Station Jacksonville even though it wasn't really filmed there.

Annual events

One of the most popular sporting events is the annual Gate River Run, the US National Championship 15K since 1994 and largest 15K race in the country. The 13,000+ recreational runners—some running for the first time—are joined by a few thousand more supporters, spectators and volunteers who make this Jacksonville's largest participation sporting event.[33] The 9.3-mile (15.0 km) race has taken place every March since 1977.[34]

Turkish Food & Music Festival.(www.jaxturkishfest.com)

The Amelia Island Concours d'Elegance, an annual event in early March, is one of the nation's premier automotive concours events.[35] Also in March is the Blessing of the Fleet and the Great Atlantic Seafood and Music Festival.

The Jacksonville Jazz Festival is held every April and is the second-largest jazz festival in the nation.[36] Springing the Blues is a free outdoor blues festival held in Jacksonville Beach, also in April.

The Tree Hill Nature Center Annual Butterfly Festival is held on the last Saturday in April. Thousands of community members visit Tree Hill for a variety of environmental learning opportunities, family arts activities and the release of over 1000 butterflies.

The Jacksonville Film Festival is staged every May and features a variety of independent films, documentaries, and shorts screening at seven historic venues in the city. Past attendees of the festival have included director John Landis and Academy Award nominee Bill Murray and winner Graham Greene, both of whom were awarded the Tortuga Verde Lifetime Achievement Award.

The World of Nations Celebration is also in May. The Spring Music Fest is a free concert on Memorial Day weekend that is sponsored by the city that features some of today's most popular artists.

Every July 4 is the Freedom, Fanfare & Fireworks celebration, one of the nation's largest fireworks displays, held at Metropolitan Park and on the surface of the St. Johns River. A very large fireworks display is also held at Jacksonville Beach, centered on the rebuilt pier.

The AT&T Greater Jacksonville Kingfish Tournament is an annual event held in July. The first contest was held in 1981 and it has grown to be the largest Kingfish tournament in the United States. Participation is limited to 1,000 boats that compete for over $500,000 in prizes, attracting approximately 30,000 spectators.

The Greater Jacksonville Agricultural Fair is held every November at the Jacksonville Fairgrounds & Exposition Center, featuring an array of carnival games and rides, food, live entertainment, vendor merchandise booths and agriculture/livestock exhibition and judging.

Planetfest, an annual corporate music festival in November, features a variety of musicians and is sponsored by the Clear Channel radio station WPLA, Planet 107.3.

Thanksgiving weekend is a busy time, with the lighting of Jacksonville's official Christmas Tree at the Jacksonville Landing on Friday, the day after Thanksgiving. The Jacksonville Light Parade happens on Saturday night following Thanksgiving.

"The World's Largest Outdoor Cocktail Party" or "Florida/Georgia-Georgia/Florida" college football game.

Attractions

The city center includes the Jacksonville Landing and the Jacksonville Riverwalks. The Landing is a popular riverfront dining and shopping venue, accessible by River Taxi from the Southbank Riverwalk. The Northbank Riverwalk runs 2.0 miles (3.2 km) along the St. Johns from Berkman Plaza to I-95 at the Fuller Warren Bridge while the Southbank Riverwalk stretches 1.2 miles (1.9 km) from the Radisson Hotel to Museum Circle.

Also on the Southbank is the Museum of Science & History. The museum, also called MOSH, features the area's only planetarium and an extensive exhibit on the history of Northeast Florida.[37]

Adjacent to Museum Circle is St. Johns River Park, also known as Friendship Park. It is the location of Friendship Fountain, one of the most recognizable and popular attractions for locals as well as tourists in Jacksonville. This landmark was built in 1965 and promoted as the “World’s Tallest and Largest” fountain at the time.

Just east of the fountain is the Jacksonville Maritime Museum, located in an enclosed pavilion on the riverwalk. Their collection includes models of ships, paintings, photographs and artifacts dating to 1562.[37]

In 2003, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) opened a 60,000-square-foot (6,000 m2) facility next to the Main Library downtown. Tracing its roots back to the formation of Jacksonville's Fine Arts Society in 1924, the museum features eclectic permanent and traveling exhibitions. In November 2006, JMOMA was renamed Museum of Contemporary Art Jacksonville (MOCA Jacksonville) to reflect their continued commitment to art produced after the modernist period.

The Museum of Science & History (MOSH) is found on Jacksonville's Southbank Riverwalk, and features a main exhibit that changes quarterly, plus three floors of nature and local history exhibits, a hands-on science area and the Alexander Brest Planetarium.

Brest, founder of Duval Engineering and Contracting Co., was also the benefactor for the Alexander Brest Museum and Gallery on the campus of Jacksonville University. The exhibits are a diverse collection of carved ivory, Pre-Columbian artifacts, Steuben glass, Chinese porcelain and Cloisonné, Tiffany glass, Boehm porcelain and rotating exhibitions containing the work of local, regional, national and international artists.[38]

Three other art galleries are located at educational institutions in town. Florida State College at Jacksonville has the Kent Gallery on their westside campus and the Wilson Center for the Arts at their main campus. The University Gallery is located on the campus of the University of North Florida.[39]

The Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens holds a large collection of European and American paintings, and a world-renowned collection of early Meissen porcelain. The museum is surrounded by three acres of formal English and Italian style gardens, and is in the Riverside neighborhood, on the bank of the St. Johns River. There is also a hands-on children's section.

The Karpeles Manuscript Library is the world’s largest private collection of original manuscripts & documents. The museum in Jacksonville is in a 1921 neoclassical building on the outskirts of downtown. In addition to document displays, there is also an antique-book library, with volumes dating from the late 1800s.

The Catherine Street Fire Station building is on the National Register of Historic Places and was relocated to Metropolitan Park in 1993. It houses the Jacksonville Fire Museum and features 500+ artifacts including an 1806 hand pumper.

The LaVilla Museum opened in 1999 and features a permanent display of African-American history. The art exhibits are changed periodically.

There are also several historical properties and items of interest in the city, including the Klutho Building, the Old Morocco Temple Building, the Palm and Cycad Arboretum, and the Prime F. Osborn III Convention Center, originally built as Union Station train depot. The Jacksonville Historical Society showcases two restoration projects: the 1887 St. Andrews Episcopal Church and the 1879 Merrill House, both located near the sports complex.

The Art Walk, a monthly outdoor art festival on the first Wednesday of each month, is sponsored by Downtown Vision, Inc, an organization which works to promote artistic talent and venues on the First Coast.

E2ride bike tours opened in 2009 and is the areas only historical bicycle tour company in Riverside-Avondale, San Marco, Olde Mandarin, Springfield and Jacksonville Beach. The bike tours are sustainable tourism, and eco tourism and include bikes, gear and guide.

The Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens boasts the second largest animal collection in the state. The zoo features elephants, lions, and, of course, jaguars (with an exhibit, Range of the Jaguar, hosted by the owners of the Jacksonville Jaguars, Delores and Wayne Weaver). It also has a multitude of reptile houses, free flight aviaries, and many other animals.

Shipwreck Island in Jacksonville Beach is the only waterpark in Duval County. It opened in 1995 and changes rides every few years to keep the season passholders coming back.

Adventure Landing in Jacksonville and Jacksonville Beach are the only amusement parks in Duval County.

Jungle Quest, located across from the Jacksonville Naval Air Station, is the only Jungle Quest store located outside of Colorado. Jungle Quest features zip-lines and rock climbing for children.

Retail

Jacksonville has three fully enclosed shopping malls. The oldest is the Regency Square Mall, which opened in 1967 and is located on former sand dunes in the Arlington area. The other is The Avenues Mall, which opened in 1990 on the Southside, at the intersection of I-95 and US 1. The Orange Park Mall is another mall located just south of the city limits in Orange Park, FL, in Clay County off of Blanding Blvd.

The end of the indoor shopping mall may be indicated by the opening of The St. Johns Town Center in 2005 and the River City Marketplace, on the Northside in 2006. Both of these are "open air" malls, with a similar mix of stores, but without being contained under a single, enclosed roof. According to the International Council of Shopping Centers (ICSC), only one enclosed mall has been built in the United States since 2006.[40]

The Avenues, Orange Park Mall, and St. John's Town Center are all owned by Simon Property Group; Regency is owned by General Growth Properties; River City Marketplace is owned by Ramco-Gershenson.

Sports

Jacksonville is home to one major league sports team—the NFL's Jaguars—and some minor league teams. Jacksonville is also home to two universities, a four year college, and the fourth largest community college in the country. All of these institutions field sports teams. Additionally, several college sports events are held in Jacksonville annually by teams and conferences not located in the city. The PGA Tour annually holds The Players Championship in nearby Ponte Vedra Beach.

Jacksonville will field a team in the new professional NRLUS rugby league competition kicks off.[41] In the 2009 AMNRL Season the Jacksonville Axemen are undefeated.[42] The Axemen also played the first cross code game between Rugby League and American Football, the Axemen defeated the Jacksonville Knights 38 to 27.[43] Jacksonville also won their first AMNRL grand final in 2010.[44]

| Club | Sport | League | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jacksonville Jaguars | Football | National Football League (NFL) - AFC | EverBank Field |

| Jacksonville Sharks | Arena football | Arena Football League | Jacksonville Veterans Memorial Arena |

| Jacksonville Knights | Football | Florida Football Alliance | Hodges Stadium |

| Jacksonville Suns | Baseball | Southern League - Southern Division | Baseball Grounds of Jacksonville |

| Jacksonville Dixie Blues | Women's Football | Women's Football Alliance | Bolles School |

| Jacksonville Breakers | Women's Ice Hockey | Florida Women's Hockey League | Jacksonville Ice |

| Jacksonville Axemen | Rugby League | American National Rugby League | Hodges Stadium |

| Duval Panthers | Minor American Football | FFAA | Jean Ribault High School |

| Jacksonville RollerGirls | Roller Derby | Women's Flat Track Derby Assocation | Jacksonville Ice/Mandarin Skate Station |

| Jacksonville Cougars | Women's Basketball | Women's Blue Chip Basketball League | Edward Waters College |

| Jacksonville University | College Baseball | NCAA - Atlantic Sun Conference | Alexander Brest Field |

| Jacksonville University | College Football | NCAA – Pioneer Football League | D.B. Milne Field |

| Jacksonville University | College Basketball | NCAA – Atlantic Sun Conference | Jacksonville Veterans Memorial Arena |

| Edward Waters College | College Football | NAIA – The Sun Conference | Earl Kitchings Stadium |

| Edward Waters College | College Basketball | NAIA – The Sun Conference | James Weldon Johnson Gymansium |

| Edward Waters College | College Baseball | NAIA – The Sun Conference | J. P. Small Historic Park |

| University of North Florida | College Basketball | NCAA – Atlantic Sun Conference | UNF Arena |

| University of North Florida | College Baseball | NCAA – Atlantic Sun Conference | Harmon Stadium |

| UNF Rugby Deadbirds | Collegiate Rugby Union | Florida Rugby Union - Division II | UNF Intramural Fields, Hodges Stadium, Deadbirds Land |

| University of North Florida | College Lacrosse | Florida Lacrosse League — Division II (FLL) | UNF Intramural Fields |

Media

The Florida Times-Union is the major daily newspaper in Jacksonville and Jacksonville.com is its official website. Another daily newspaper focused on the legal community is the Financial News and Daily Record.

The city's chief alternative newsweekly is Folio Weekly. Others include EU Jacksonville, Buzz Magazine and the Jacksonville Observer. The Jacksonville Business Journal is a weekly paper that focuses on the local economy and business community. The Jacksonville Free Press is a weekly paper serving the African-American community.

Jacksonville is the 47th largest local television market in the United States,[45] and is served by television stations affiliated with major American networks including WTLV (NBC), WJXX (ABC), WTEV (CBS), WAWS (Fox/My Network TV), WJCT (PBS),and WCWJ (CW). WJXT is a former longtime CBS affiliate that turned independent in 2002.

The website, Jax4Kids.com is a resource available to Jacksonville-area parents, grandparents and educators to find current and upcoming events, classes, camps, sports and other programs for cultural and educational enrichment for children.

Jacksonville is the 46th largest local radio market in the United States,[46] and is dominated by the same two large ownership groups that dominate the radio industry across the United States: Cox Radio[47] and Clear Channel Communications.[48] The dominant AM radio station in terms of ratings is WOKV 690AM, which is also the flagship station for the Jacksonville Jaguars.[49] In September 2006, WOKV began simulcasting on 106.5 FM as WOKV FM. There are two radio stations broadcasting a primarily contemporary hits format; WAPE 95.1 has dominated this niche for over twenty years, and more recently has been challenged by WFKS 97.9 FM (KISS FM). WJBT 93.3 (The Beat) is a hip-hop/R&B station, WPLA 107.3 is a modern rock and Alternative rock station that competes with WXXJ 102.9, WFYV 104.5—Rock 105 Jacksonville Classic rock, WQIK 99.1 is a country station as well as WGNE-FM 99.9, WCRJ FM 88.1 (The Promise) is the main Contemporary Christian station operating since 1984, WHJX 105.7 and WFJO 92.5 plays music in Spanish like salsa, merengue, and reggaeton, and WJCT 89.9 is the local National Public Radio affiliate. Local Jones College also hosts an easy listening station, WKTZ 90.9 FM.

Demographics

| Historical populations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 1,045 |

|

|

| 1860 | 2,118 | 102.7% | |

| 1870 | 6,912 | 226.3% | |

| 1880 | 7,650 | 10.7% | |

| 1890 | 17,201 | 124.8% | |

| 1900 | 28,429 | 65.3% | |

| 1910 | 57,699 | 103.0% | |

| 1920 | 91,558 | 58.7% | |

| 1930 | 129,549 | 41.5% | |

| 1940 | 173,065 | 33.6% | |

| 1950 | 204,275 | 18.0% | |

| 1960 | 201,030 | −1.6% | |

| 1970 | 528,865 | 163.1% | |

| 1980 | 540,920 | 2.3% | |

| 1990 | 635,230 | 17.4% | |

| 2000 | 735,503 | 15.8% | |

| Est. 2010 | 813,518 | 10.6% | |

Jacksonville is the most populous city in Florida, and the twelfth most populous city in the United States. As of the census estimates of 2006, there were 799,875 people, 315,796 households, and 199,037 families residing in the city. However, it is perhaps misleading to compare Jacksonville's population to other major cities. As a result of the 1968 consolidation of Jacksonville and Duval County, most of the suburban communities of Jacksonville were absorbed within the city limits of Jacksonville proper. It may be a more accurate comparison to compare the incorporated area of Jacksonville to the Metropolitan area of other cities.

The population density was 374.9/km² (970.9/mi²). There were 308,826 housing units at an average density of 157.4/km² (407.6/mi²). The racial makeup of the city was 64.48% White, 34.03% Black or African American, 0.34% Native American, 2.78% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 1.33% from other races, and 1.99% from two or more races. 4.16% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. The largest ancestries include: German (9.6%), American (9.3%), Irish (9.0%), English (8.5%), and Italian (3.5%). Jacksonville has, as named by the United States Census the 10th largest Arab population in the United States. Also Jacksonville has a large Filipino population, in part related to their tradition of service with the Navy. In addition, there is a large Serbo-Croatian population, located mostly on the south side of Jacksonville, and Russian population. Jacksonville also has a growing Puerto Rican population.

According to the 2006-2008 American Community Survey, the racial composition of Jacksonville was as follows:

- White: 62.3% (Non-Hispanic Whites: 58.3% )

- Black or African American: 30.1%

- American Indian: 0.3%

- Asian: 3.5%

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: 0.1%

- Some other race: 1.8%

- Two or more races: 1.9%

- Hispanic or Latino (of any race): 6.2%

Source:[50]

There were 284,499 households out of which 33.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.7% were married couples living together, 16.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 33.0% were non-families. 26.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 7.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.53 and the average family size was 3.07. In the city, the population was spread out with 26.7% under the age of 18, 9.7% from 18 to 24, 32.3% from 25 to 44, 21.0% from 45 to 64, and 10.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females there were 93.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.6 males.

In 2000, the median income for a household in the city was $40,316, and the median income for a family was $47,243. Males had a median income of $32,547 versus $25,886 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,337. About 9.4% of families and 12.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 16.7% of those under age 18 and 12.0% of those age 65 or over.

Languages

As of the 2006–2008 American Community Survey, 88.1% of Jacksonville's population age five and over spoke only English at home while 5.2% of the population spoke Spanish at home. About 3.2% spoke other Indo-European languages at home. About 2.5% spoke an Asian language at home. The remaining 0.9% of the population spoke other languages at home.[51]

Religion

Jacksonville has a diverse religious population. The city is estimated to contain 265,158 Evangelical Protestants and 89,649 Mainline Protestants who attend a total of 794 churches. Several of these are megachurches, including First Baptist Church downtown and Christ's Church (formerly Mandarin Christian Church) on Greenland Road. Jacksonville is part of the Roman Catholic Diocese of St. Augustine, which has 166,464 registered members attending 51 parishes.[52] Since 1906, the city's Unitarian Universalists have worshipped at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Jacksonville.[53] The Episcopal Diocese of Florida has its see in St. John's Cathedral, the current building dating from 1906. There is a good representation of various Lutheran Synods, as well. The greater metropolitan area also has a Jewish population of 14,000, mostly residing in the neighborhood of Mandarin. There are two Reform, four Conservative, and four Orthodox synagogues, three of them Chabad-affiliated.[54] There are over 3,000 members of various Eastern Orthodox Church jurisdictions in eight parishes or missions, and 18,050 of other religious affiliations. Within the city limits there are also seven Mormon church buildings housing twelve congregations of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,[55] a population of Muslims centered on the Islamic Center of Northeast Florida,[56] a Bahá'í center,[57] and New Age and Neopagan communities.[58]

Law and government

Administrative structure

The most noteworthy feature of Jacksonville government is its consolidated nature. The Duval County-Jacksonville consolidation eliminated any type of separate county executive or legislature, and supplanted these positions with the Mayor of Jacksonville and the City Council of the City of Jacksonville, respectively. Because of this, voters who live outside of the city limits of Jacksonville, but inside of Duval County, are allowed not only to vote in elections for these positions, but to run for them as well. In fact, in 1995, John Delaney, a resident of Neptune Beach, was elected mayor of the city of Jacksonville.

Jacksonville uses the Mayor-Council form of city government, also called the Strong-Mayor form, in which a mayor serves as the city's Chief Executive and Administrative officer. The mayor holds veto power over all resolutions and ordinances made by the city council, and also has the power to hire and fire the head of various city departments. The current mayor is John Peyton.

Law enforcement

Jacksonville and Duval County historically maintained separate police agencies: the Jacksonville Police Department and Duval County Sheriff's Office. As part of consolidation in 1968, the two merged, creating the Jacksonville Sheriff's Office (JSO). The JSO is headed by the elected Sheriff of Duval County, currently John Rutherford, and is responsible for law enforcement and corrections in the county.

Crime

In 2006, based on the United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation-Uniform Crime Reports, Jacksonville reported 6,663 violent crimes including 110 murders.[59] In 2006 Duval County had the highest murder rate in Florida.[60] Rates for other crimes were significantly lower; based on the Morgan Quitno Press 2006 national crime rankings, Jacksonville ranked as the 10th safest among the 32 US cities with a population of 500,000 or more.[61] In 2009 a report by the Federal Bureau of Investigation ranked Jacksonville 115th in a list of "most dangerous" large cities in the United States, behind other Florida cities including Orlando (11th), Miami (35th), Tampa (74th), and Gainesville (101st).[62]

Autonomous agencies

Some government services remained — as they had been before consolidation – independent of both city and county authority. In accordance with Florida law, the school board continues to exist with nearly complete autonomy. Jacksonville also has several quasi-independent government agencies which only nominally answer to the consolidated authority, including electric authority, port authority, transportation authority, housing authority and airport authority. The main environmental and agricultural body is the Duval County Soil and Water Conservation District, which works closely with other area and state agencies.

Education

Higher education

Jacksonville is home to Jacksonville University, the University of North Florida, Florida State College at Jacksonville, Edward Waters College, The Art Institute of Jacksonville, Florida Coastal School of Law, Trinity Baptist College, Jones College, Fortis College[63] and Florida Technical College.

Former mayor John Delaney has been president of the University of North Florida since leaving office in July 2003.

Primary and secondary education

Public schools in Duval County are controlled by the Duval County School Board. The county is home to four of the nation's best high schools: (Stanton College Preparatory School 5th, Paxon School for Advanced Studies 6th, Mandarin High School 151st, and Douglas Anderson School of the Arts 158th,) according to Newsweek Magazine in 2008.

Jacksonville, along with the standard district schools, is home to three International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme ("IB") high schools. They are Stanton, Paxon, and Jean Ribault High School. Jacksonville also has a notable magnet high school devoted to the performing and expressive arts, Douglas Anderson. The Advanced International Certificate of Education Program (AICE) is available at Mandarin High School, Duncan U. Fletcher High School and William M. Raines High School.

Private schools

Some of the larger private schools in Jacksonville include the Bolles School , Episcopal High School, Trinity Christian Academy, and Providence School, as well as two Catholic high schools, Bishop Kenny High School and Bishop John J. Snyder High School.[64] There are a number of smaller private Christian and Catholic schools.

See also: List of high schools in Jacksonville

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Libraries

The Jacksonville Public Library had its beginnings when May Moore and Florence Murphy started the "Jacksonville Library and Literary Association" in 1878. The Association was populated by various prominent Jacksonville residents and sought to create a free public library and reading room for the city.[65]

Over the course of 127 years, the system has grown from that one room library to become one of the largest in the state. The Jacksonville library system has twenty branches, ranging in size from the 54,000 sq ft (5,000 m2) West Regional Library to smaller neighborhood libraries like Westbrook and Eastside. The Library annually receives nearly 4 million visitors and circulates over 6 million items. Nearly 500,000 library cards are held by area residents.[66]

On November 12, 2005, the new 300,000 sq ft (30,000 m2) Main Library opened to the public, replacing the 40-year old Haydon Burns Library. The largest public library in the state, the opening of the new main library marked the completion of an unprecedented period of growth for the system under the Better Jacksonville Plan.[67] The new Main Library offers specialized reading rooms, public access to hundreds of computers and public displays of art, an extensive collection of books, and special collections ranging from the African-American Collection to the recently opened Holocaust Collection.[65]

Economy

Business climate

Jacksonville's location on the St. Johns River and the Atlantic Ocean proved providential in the growth of the city and its industry. The largest city in the state, it is also the largest deepwater port in the south (as well as the second-largest port on the U.S. East coast) and a leading port in the U.S. for automobile imports, as well as the leading transportation and distribution hub in the state. However, the strength of the city's economy lies in its broad diversification. While the area once had many thriving dairies such as Gustafson's Farm and Skinner Dairy, this aspect of the economy has declined over time. The area's economy is balanced among distribution, financial services, biomedical technology, consumer goods, information services, manufacturing, insurance and other industries.

Jacksonville is a rail, air, and highway focal point and a busy port of entry, with Jacksonville International Airport, ship repair yards and extensive freight-handling facilities. Lumber, phosphate, paper, cigars and wood pulp are the principal exports; automobiles and coffee are among imports. The city also has a large and diverse manufacturing base. According to Forbes in 2007, Jacksonville, Florida ranked 3rd in the top ten U.S. cities to relocate to find a job.[68] Jacksonville was also the 10th fastest growing city in the U.S.[69]

Cecil Commerce Center is located on the site of the former Naval Air Station Cecil Field which closed in 1999 following the 1993 Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) decision. Covering a total area of 22,939 acres (92.83 km2), it was the largest military base in the Jacksonville area. The parcel contains more than 3% of the total land area in Duval County (17,000 acres). The industrial and commercial-zoned center offers mid to large-size parcels for development and boasts excellent transportation and utility infrastructure as well as the third-longest runway in Florida.

Companies

Jacksonville is home to many prominent corporations & organizations including three Fortune 500 Companies: CSX Corporation, Fidelity National Financial and Winn-Dixie Stores, Inc.. Fortune Magazine identified Landstar System, MPS Group and PSS World Medical as the best big companies in Jacksonville in 2009.[70]

Military

Jacksonville is home to multiple military facilities, and with Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay nearby gives Jacksonville the third largest military presence in the country.[71] Only Norfolk, Virginia and San Diego, California are bigger. The military is by far the largest employer in Jacksonville and their total economic impact is approximately $6.1 billion annually.[72]

Naval Air Station Jacksonville is a military airport located four miles (6 km) south of the central business district. Approximately 23,000 civilian and active-duty personnel are employed on the base. There are 35 operational units/squadrons assigned there and support facilities include an airfield for pilot training, a maintenance depot capable of virtually any task, from changing a tire to intricate micro-electronics or total engine disassembly. Also on-site is a Naval Hospital, a Fleet Industrial Supply Center, a Navy Family Service Center, and recreational facilities.

Naval Station Mayport is a Navy Ship Base that is the third largest fleet concentration area in the United States. Mayport's operational composition is unique, with a busy harbor capable of accommodating 34 ships and an 8,000-foot (2,400 m) runway capable of handling any aircraft used by the Department of Defense. Until 2007, it was home to the aircraft carrier USS John F. Kennedy, which locals called "Big John". In January 2009, the Navy committed to stationing a nuclear-powered carrier at Mayport when the official Record of Decision was signed. The port will require approximately $500 million in facility enhancements to support the larger vessel, which will take several years to complete. The ship is projected to arrive in 2014.[73]

Blount Island Command is a Marine Corps Logistics Base whose mission is to support the Maritime Prepositioning Force (MPF) which provides for rapid deployment of personnel to link up with prepositioned equipment and supplies embarked aboard forward deployed Maritime Prepositioning Ships (MPS).

USS Jacksonville, a nuclear powered Los Angeles class submarine, is the only US Navy ship named for the city. The ship's nickname is The Bold One and Norfolk, Virginia is her home port.

The Florida Air National Guard is based at Jacksonville International Airport.

Coast Guard Sector Jacksonville is located on the St. Johns River next to Naval Station Mayport. Sector Jacksonville controls operations from Kings Bay, GA south to Cape Canaveral, FL. The CGC Kingfisher, CGC Maria Bray, and CGC Hammer are stationed at the Sector. Station Mayport is co-located with Sector Jacksonville and includes 25 foot Response Boats, and 47 foot Motor Life Boats.

Port

The Port of Jacksonville, a seaport on the St. Johns River, is a large component of the local economy. Approximately 50,000 jobs in Northeast Florida are related to port activity and the port has an economic impact of $2.7 billion in Northeast Florida:[74]

- Port wages and salaries = $1.3 billion

- Business revenue = $743 million

- Local purchases = $239.1 million

- State and local taxes = $119.3 million

- Customs revenue = $258 million

Tourism

In 2008, Jacksonville had approximately 2.8 million visitors who stayed overnight, spending nearly $1 billion. Research Data Services of Tampa was commissioned to undertake the study, which quantified the importance of tourism. The total economic impact was $1.6 billion and supported nearly 43,000 jobs, 10% of the local workforce.[75]

Infrastructure

Health systems

Major players in the Jacksonville health care industry include St. Vincent's HealthCare, Baptist Health and Shands HealthCare for local residents. Additionally, Nemours Children's Hospital and Mayo Clinic Hospital each draw patients regionally.

Housing

The Jacksonville Housing Authority (JHA) is the quasi-independent agency responsible for public housing and subsidized housing in Jacksonville. The Mayor and City Council of Jacksonville established the JHA in 1994 to create an effective, community service oriented, public housing agency with innovative ideas and a different attitude. The primary goal was to provide safe, clean, affordable housing for eligible low and moderate income families, the elderly, and persons with disabilities. The secondary goal was to provide effective social services, work with residents to improve their quality of life, encourage employment and self-sufficiency, and help residents move out of assisted housing. To that end, JHA works with HabiJax to help low and moderate income families to escape the public housing cycle and become successful, productive, homeowners and taxpayers.

Non-profit/service organizations

The TaxExemptWorld.com website, which compiles Internal Revenue Service data, reported that in 2007, there are 2,910 distinct, active, tax exempt/non-profit organizations in Jacksonville which, excluding Credit Unions, had a total income of $7.08 billion and assets of $9.54 billion.[76] There are 333 charitable organizations with assets of over $1 million. The largest share of assets was tied to Medical facilities, $4.5 billion. The problems of the homeless are addressed by several non-profits, most notably the Sulzbacher Center and the Clara White Mission.

Utilities

Basic utilities in Jacksonville (water, sewer, electric) are provided by the JEA (formerly Jacksonville Electric Authority). According to Article 21 of the Jacksonville City Charter, "JEA is authorized to own, manage and operate a utilities system within and outside the City of Jacksonville. JEA is created for the express purpose of acquiring, constructing, operating, financing and otherwise have plenary authority with respect to electric, water, sewer, natural gas and such other utility systems as may be under its control now or in the future."

- People's Gas is Jacksonville's natural gas provider.

- Comcast is Jacksonville's local cable provider.

- AT&T (formerly BellSouth) is Jacksonville's local phone provider.

- AT&T's U-Verse service provides TV, internet, and VoIP phone service to customers served by fiber-to-the-premises or fiber-to-the-node using a VRAD.

The city has a successful recycling program with separate pickups for garbage, yard waste and recycling. Collection is provided by several private companies under contract to the City of Jacksonville.

Transportation

Highways

- Interstate highways

Interstate 10

Interstate 10 Interstate 95

Interstate 95 Interstate 295

Interstate 295

Interstate Highways 10 and 95 intersect in Jacksonville, creating the busiest intersection in the region with 200,000 vehicles each day.[77] Interstate 10 ends at this intersection (the other end being in Santa Monica, California). The eastern terminus of US-90 is in nearby Jacksonville Beach near the Atlantic Ocean. Additionally, several other roads as well a major local expressway, J. Turner Butler Boulevard (SR 202) also connect Jacksonville to the beaches. Interstate 95 has a bypass route, with I-295, which bypasses the city to the west, and SR-9A, bypassing the city to the east. The major interchange at SR 9A and SR 202 (Butler Blvd) was finally completed on December 24, 2008. The interchange at I-95 and I-295 is scheduled to be completed in the summer of 2010, then SR 9A will be re-signed I-295 and the interstate will therefore circumscribe the most populated portion of Jacksonville.[78]

Mass transit

Public transportation provided by the Jacksonville Transportation Authority (JTA) includes regular and express bus service, downtown trolleys, JTA Connexion (paratransit) and the stadium shuttle. The JTA Skyway is an elevated monorail which travels 2.5 miles from the King Street parking garage across the St. Johns River and through the central business district, ending at the Convention Center or the Florida State College at Jacksonville downtown campus. Intermediate stops include the government center, central business area and two buildings on the southbank. It was not intended to serve the Jacksonville Sports complex (Stadium, Baseball Park or Arena) and is of limited help for most downtown commuters unless they live on the southside and work in a building close to a skyway station.

Railroads

Jacksonville is the headquarters of two significant freight railroads. CSX Transportation, owns a large building on the downtown riverbank that is a significant part of the skyline. Florida East Coast Railway also calls Jacksonville home.

Amtrak serves Jacksonville by the daily Silver Meteor and Silver Star long distance trains. The current station is situated on Clifford Lane in the northwest section of the city.

Jacksonville was also served by the thrice-weekly Sunset Limited and the daily Silver Palm. Service on the Silver Palm was cut back to Savannah, Georgia in 2002. The Sunset Limited route was truncated at San Antonio, Texas as a result of the track damage in the Gulf Coast area caused by Hurricane Katrina on August 28, 2005. Service was restored as far east as New Orleans by late October 2005, but Amtrak has opted not to fully restore service into Florida. This appears to be more of a managerial and political issue than a physical one.[79] Advocates for the train's restoration have pointed to revenue figures for Amtrak's fiscal year 2004 (the last full year of coast-to-coast Sunset Limited service), noting that the Orlando-New Orleans segment accounted for 41% of the Sunset's revenue.[80]

Airports

Airports in Jacksonville are managed by the Jacksonville Aviation Authority (JAA). The commercial passenger facility is Jacksonville International Airport on the Northside. Smaller planes can fly to Craig Municipal Airport in Arlington and Herlong Airport on the Westside. The JAA also operates Cecil Field, the former NAS airfield at Cecil Commerce Center that is intended for the aerospace and manufacturing companies located there.

Seaports

Public seaports in Jacksonville are managed by the Jacksonville Port Authority, known as JAXPORT. Four modern deepwater (38 ft) seaport facilities, including America's newest cruise port, make Jacksonville a full-service international seaport. In FY2006, JAXPORT handled 8.7 million tons of cargo, including nearly 610,000 vehicles, which ranks Jacksonville 2nd in the nation in automobile handling, behind only the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.[81]

The 20 other maritime facilities not managed by the Port Authority move about 10 million tons of additional cargo in and out of the St. Johns River. In terms of total tonnage, the Port of Jacksonville ranks 40th nationally; within Florida, it is 3rd behind Tampa and Port Everglades.

In 2003, the JAXPORT Cruise Terminal opened, providing cruise service for 1,500 passengers to Key West, Florida, the Bahamas, and Mexico via Carnival Cruise Lines ship, Celebration, which was retired in April, 2008. For almost five months, no cruises originated from Jacksonville until September 20, 2008, when the cruise ship Fascination departed with 2,079 passengers.[82] In Fiscal year 2006, there were 78 cruise ship sailings with 128,745 passengers.[83] A JaxPort spokesperson said in 2008 that they expect 170,000 passengers to sail each year.[84]

Bridges

There are seven bridges over the St. Johns River at Jacksonville. They include (starting from furthest downstream) the Dames Point Bridge, the Mathews Bridge, the Isaiah D. Hart Bridge, the Main Street Bridge, the Acosta Bridge, the Fuller Warren Bridge (which carries I-95 traffic) and the Buckman Bridge (which carries I-295 traffic).

Beginning in 1953, tolls were charged on the Hart, Mathews, Fuller Warren and the Main Street bridges to pay for bridge construction, renovations and many other highway projects. As Jacksonville grew, toll plazas created bottlenecks and caused delays and accidents during rush hours. In 1988, Jacksonville voters chose to eliminate toll collection and replace the revenue with a ½ cent local sales tax increase. In 1989, the toll booths were removed.

The Mayport Ferry connects the north and south ends of State Road A1A between Mayport and Fort George Island, and is the last active ferry in Florida. The state of Florida transferred responsibility for ferry operations to JAXPORT on October 1, 2007.

A 1992 map of downtown Jacksonville showing three road bridges. |

Acosta Bridge |

Mathews Bridge with the Hart Bridge in the background. |

Fuller Warren Bridge |

|

Main St Bridge |

Hart Bridge |

Dames Point Bridge |

Buckman Bridge |

|

|||||||||||

Sister cities

Jacksonville has eight sister cities.[85] They are: