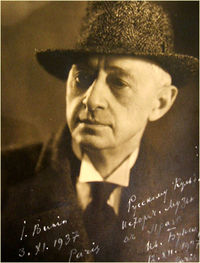

Ivan Bunin

| Ivan Bunin | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Ivan Alekseyevich Bunin October 22, 1870 Voronezh, Russian Empire |

| Died | November 8, 1953 (aged 83) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Short story writer |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Notable award(s) | Nobel Prize in Literature 1933 |

Ivan Alekseyevich Bunin (Russian: Ива́н Алексе́евич Бу́нин; October 22 [O.S. October 10] 1870 – November 8, 1953) was the first Russian writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. The texture of his poems and stories, sometimes referred to as "Bunin brocade", is one of the richest in the language. In the words of Soviet-era writer K.G. Paustovsky, the 1930 novel Life of Arseniev is not only an apical work of written Russian, but also "one of the remarkable occurrences of world literature."[1]

Contents |

Early life

Bunin was born on his parents' estate in Voronezh province in central Russia. He came from a long line of landed gentry and serf owners, but his grandfather and father had squandered nearly all of the estate.

He was sent to the public school in Yelets (Lipetskaya Oblast) in 1881, but had to return home after five years. His brother, who was university-educated, encouraged him to read the Russian classics and to write.

At 17, he published his first poem in 1887 in a Saint Petersburg literary magazine. His first collection of poems, Listopad (1901), was warmly welcomed by critics. Although his poems are said to continue the 19th-century traditions of the Parnassian poets, they are steeped in oriental mysticism and sparkle with striking, carefully chosen epithets. Vladimir Nabokov was a great admirer of Bunin's verse, comparing him with Alexander Blok, but scorned his prose.

In 1889, he followed his brother to Kharkov, where he became a government clerk, assistant editor of a local paper, librarian, and court statistician. Bunin also began a correspondence with Anton Chekhov, with whom he became close friends. He also had a more distant relationship with Maxim Gorky and Leo Tolstoy.

In 1891, he published his first short story, "Country Sketch" in a literary journal. As the time went by, he switched from writing poems to short stories. His first acclaimed novellas were "On the Farm," "The News From Home," "To the Edge of the World," "Antonov Apples," and "The Gentleman from San Francisco," the latter being his most representative piece and the one translated in English by D. H. Lawrence.

Bunin was a well-known translator himself. The best known of his translations is Longfellow's "The Song of Hiawatha" for which Bunin was awarded the Pushkin Prize in 1903. He also did translations of Byron, Tennyson, and Musset. In 1909, he was elected to the Russian Academy.

Renown

From 1895, Bunin divided his time between Moscow and Saint Petersburg. He married the daughter of a Greek revolutionary in 1898, but the marriage ended in divorce, their only child died at the age of five. Although he remarried (his second wife was Vera Muromtseva, whom he met in 1906 at her uncle's house), Bunin's romances with other women continued right up to the end of his life. His tempestuous private life in emigration is the subject of the internationally acclaimed Russian movie, His Wife's Diary (or The Diary of His Wife) (Дневник его жены) (2000)[2].

Bunin published his first full-length work, The Village, when he was 40. It was a bleak portrayal of village life, with its stupidity, brutality, and violence. Its harsh realism, "the characters having sunk so far below the average of intelligence as to be scarcely human," brought him in touch with Maxim Gorky. Two years later, he published Dry Valley, which was a veiled portrayal of his family.

Before World War I, Bunin traveled in Ceylon, Palestine, Egypt, and Turkey, and these travels left their mark on his writing. He spent the winters from 1912 to 1914 on Capri with Gorky.

Emigration

Bunin left Moscow after the revolution in 1917, moving to Odessa. He left Odessa on the last French ship in 1919 and settled in Grasse, France. There, he published his diary The Accursed Days, which voiced his aristocratic aversion to the Bolshevik regime. About the Soviet government he wrote: "What a disgusting gallery of convicts!"

Bunin was much lionized in the emigration, where he came to be viewed as the eldest of living Russian writers in the tradition of Tolstoy and Chekhov. Accordingly, he was the first Russian to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1933. On the journey through Germany to accept the prize in Stockholm, he was detained by the Nazis, ostensibly for jewel smuggling, and forced to drink a bottle of castor oil.

In the 1930s, Bunin published two parts of a projected autobiographical trilogy: The Life of Arsenyev and Lika, which were "neither a short novel, nor a novel, nor a long short story, but . . . of a genre yet unknown." Later, he worked upon his celebrated cycle of nostalgic stories with a strong erotic undercurrent and a Proustian ring. They were published as the Dark Avenues or The Dark Alleys in 1943.

Bunin was a strong opponent of the Nazis and sheltered a Jewish writer in his house in Grasse after Vichy France was occupied by the Germans.

Decline and death

Towards the end of his life, he became interested in Soviet literature and even entertained plans of returning to Russia, as Aleksandr Kuprin had done before. Bunin died of a heart attack in a Paris attic flat, while his invaluable book of reminiscences on Chekhov was still unfinished. He was buried in the Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Russian Cemetery. Several years later, during the Khrushchev thaw, his works were allowed for publication in the Soviet Union.

Additional reading

- Night of Denial: Stories and Novellas, Ivan Bunin. Trans. Robert Bowie. Northwestern 2006 ISBN 0-8101-1403-8

- The Life of Arseniev, Ivan Bunin. edited by Andrew Baruch Wachtel. Northwestern 1994 ISBN 0-8101-1172-1

- Dark Avenues, Ivan Bunin. Translated by Hugh Aplin. Oneworld Classics 2008 ISBN 978-1847490476

References

- ↑ Igor Yanin, Ivan Alekseevich Bunin, Biography (in Russian), http://bunin.niv.ru/ accessed 21 July 2009.

- ↑ IMDb.com Page for The Diary of His Wife

External links

- Biography in English

- Biography

- Ivan Bunin's Gravesite

- Ivan Bunin in The Literary Encyclopedia

- (Russian) Bunin: biography, photos, poems, prose, diaries, critical essays

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||

.jpg)