Isotope

Isotopes are different types of atoms (nuclides) of the same chemical element, each having a different number of neutrons. In a corresponding manner, isotopes differ in mass number (or number of nucleons) but never in atomic number.[1] The number of protons (the atomic number) is the same because that is what characterizes a chemical element. For example, carbon-12, carbon-13 and carbon-14 are three isotopes of the element carbon with mass numbers 12, 13 and 14, respectively. The atomic number of carbon is 6, so the neutron numbers in these isotopes of carbon are therefore 12−6 = 6, 13−6 = 7, and 14–6 = 8, respectively.

A nuclide is an atomic nucleus with a specified composition of protons and neutrons. The nuclide concept emphasizes nuclear properties over chemical properties, while the isotope concept emphasizes chemical over nuclear. The neutron number has drastic effects on nuclear properties, but negligible effects on chemical properties. Since isotope is the older term, it is better known, and is still sometimes used in contexts where nuclide might be more appropriate, such as nuclear technology.

An isotope and/or nuclide is specified by the name of the particular element (this indicates the atomic number implicitly) followed by a hyphen and the mass number (e.g. helium-3, carbon-12, carbon-13, iodine-131 and uranium-238). When a chemical symbol is used, e.g., "C" for carbon, standard notation is to indicate the number of nucleons with a superscript at the upper left of the chemical symbol and to indicate the atomic number with a subscript at the lower left (e.g. 32He, 42He, 126C, 146C, 23592U, and 23992U).

Some isotopes are radioactive and are therefore described as radioisotopes or radionuclides, while others have never been observed to undergo radioactive decay and are described as stable isotopes. For example, 14C is a radioactive form of carbon while 12C and 13C are stable isotopes. There are about 339 naturally occurring nuclides on Earth[2], of which 288 are primordial nuclides. These include 31 nuclides with very long half lives (over 80 million years) and 257 which are formally considered as "stable"[2]. About 30 of these "stable" isotopes have actually been observed to decay, but with half lives too long to be estimated so far. This leaves 227 nuclides that have not been observed to decay at all.

Many more apparently "stable" isotopes are predicted by theory to be radioactive, with extremely long half-lives (this does not count the posibility of proton decay, which would make all nuclides unstable). Of the 227 nuclides never observed to decay, only 90 of these (all from the first 40 elements) are stable in theory to all known forms of decay. Element 41 (niobium) is theoretically unstable to spontaneous fission, but this has never been detected. Many other stable nuclides are in theory energetically susceptible to other known forms of decay such as alpha decay or double beta decay, but no decay has yet been observed. The half lives for these processes often exceed a million times the estimated age of the universe.

Adding in the radioactive nuclides that have been created artificially, there are more than 3100 currently known nuclides.[3]. These include 905 nuclides which are either stable, or have half lives longer than 60 minutes. See list of nuclides for details.

Contents

|

History of the term

The term isotope was coined in 1913 by Margaret Todd, a Scottish physician, during a conversation with Frederick Soddy (to whom she was distantly related by marriage).[4] Soddy, a chemist at Glasgow University, explained that it appeared from his investigations as if each position in the periodic table was occupied by multiple entities. Hence Todd made the suggestion, which Soddy adopted, that a suitable name for such an entity would be the Greek term for "at the same place".

Soddy's own studies were of radioactive (unstable) atoms. The first observation of different stable isotopes for an element was by J. J. Thomson in 1913. As part of his exploration into the composition of canal rays, Thomson channeled streams of neon ions through a magnetic and an electric field and measured their deflection by placing a photographic plate in their path. Each stream created a glowing patch on the plate at the point it struck. Thomson observed two separate patches of light on the photographic plate (see image), which suggested two different parabolas of deflection. Thomson eventually concluded that some of the atoms in the neon gas were of higher mass than the rest. F.W. Aston subsequently discovered different stable isotopes for numerous elements using a mass spectrograph.

Variation in properties between isotopes

Chemical and molecular properties

A neutral atom has the same number of electrons as protons. Thus, different isotopes of a given element all have the same number of protons and electrons and share a similar electronic structure. Because the chemical behavior of an atom is largely determined by its electronic structure, different isotopes exhibit nearly identical chemical behavior. The main exception to this is the kinetic isotope effect: due to their larger masses, heavier isotopes tend to react somewhat more slowly than lighter isotopes of the same element. This is most pronounced for protium (1H) and deuterium (2H), because deuterium has twice the mass of protium. The mass effect between deuterium and the relatively light protium also affects the behavior of their respective chemical bonds, by means of changing the center of gravity (reduced mass) of the atomic systems. However, for heavier elements, which have more neutrons than lighter elements, the ratio of the nuclear mass to the collective electronic mass is far greater, and the relative mass difference between isotopes is much less. For these two reasons, the mass-difference effects on chemistry are usually negligible.

In similar manner, two molecules that differ only in the isotopic nature of their atoms (isotopologues) will have identical electronic structure and therefore almost indistinguishable physical and chemical properties (again with deuterium providing the primary exception to this rule). The vibrational modes of a molecule are determined by its shape and by the masses of its constituent atoms. As a consequence, isotopologues will have different sets of vibrational modes. Since vibrational modes allow a molecule to absorb photons of corresponding energies, isotopologues have different optical properties in the infrared range.

Nuclear properties and stability

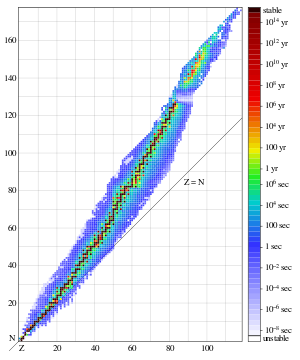

Atomic nuclei consist of protons and neutrons bound together by the residual strong force. Because protons are positively charged, they repel each other. Neutrons, which are electrically neutral, stabilize the nucleus in two ways. Their copresence pushes protons slightly apart, reducing the electrostatic repulsion between the protons, and they exert the attractive nuclear force on each other and on protons. For this reason, one or more neutrons are necessary for two or more protons to be bound into a nucleus. As the number of protons increases, so does the ratio of neutrons to protons necessary to ensure a stable nucleus (see graph at right). For example, although the neutron:proton ratio of 32He is 1:2, the neutron:proton ratio of 23892U is greater than 3:2. A number of lighter elements have stable nuclides with the ratio 1:1 (Z = N). The nuclide 4020Ca (calcium-40) is the heaviest stable nuclide with the same number of neutrons and protons; all heavier stable nuclides contain more neutrons than protons.

Numbers of isotopes per element

Of the 80 elements with a stable isotope, the largest number of stable isotopes observed for any element is ten (for the element tin). Xenon is the only element that has nine stable isotopes. Cadmium has eight stable isotopes. Five elements have seven stable isotopes, eight have six stable isotopes, ten have five stable isotopes, eight have four stable isotopes, nine have three stable isotopes, 16 have two stable isotopes (counting 180m73Ta as stable), and 26 elements have only a single stable isotope (of these, 19 are so-called mononuclidic elements, having a single primordial stable isotope that dominates and fixes the atomic weight of the natural element to high precision; 3 radioactive mononuclidic elements occur as well).[5] In total, there are 257 nuclides that have not been observed to decay. For the 80 elements that have one or more stable isotopes, the average number of stable isotopes is 257/80 = 3.2 isotopes per element.

Even and odd nucleon numbers

| Mass | E | O | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable | 145 | 101 | 246 |

| Longlived | 20 | 6 | 26 |

| Primordial | 165 | 107 | 272 |

The proton:neutron ratio is not the only factor affecting nuclear stability. Adding neutrons to isotopes can vary their nuclear spins and nuclear shapes, causing differences in neutron capture cross-sections and gamma spectroscopy and nuclear magnetic resonance properties.

Even mass number

Beta decay of an even-even nucleus produces an odd-odd nucleus, and vice versa. An even number of protons or of neutrons are more stable (lower binding energy) because of pairing effects, so even-even nuclei are much more stable than odd-odd. One effect is that there are few stable odd-odd nuclei, but another effect is to prevent beta decay of many even-even nuclei into another even-even nucleus of the same mass number but lower energy, because decay proceeding one step at a time would have to pass through an odd-odd nucleus of higher energy. This makes for a larger number of stable even-even nuclei, up to three for some mass numbers, and up to seven for some atomic (proton) numbers. Double beta decay directly from even-even to even-even skipping over an odd-odd nuclide is only occasionally possible, and even then with a half-life greater than a billion times the age of the universe.

Even-mass-number nuclides have integer spin and are bosons.

Even proton-even neutron

| p,n | EE | OO | EO | OE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable | 140 | 5 | 53 | 48 |

| Longlived | 16 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Primordial | 156 | 9 | 55 | 52 |

For example, the extreme stability of helium-4 due to a double pairing of 2 protons and 2 neutrons prevents any nuclides containing five or eight nucleons from existing for long enough to serve as platforms for the buildup of heavier elements during fusion formation in stars (see triple alpha process).

There are 141 stable even-even isotopes, forming 55% of the 257 stable isotopes. There are also 16 primordial longlived even-even isotopes. As a result, many of the 41 even-numbered elements from 2 to 82 have many primordial isotopes. Half of these even-numbered elements have six or more stable isotopes.

All even-even nuclides have spin 0 in their ground state.

Odd proton-odd neutron

Only five stable nuclides contain both an odd number of protons and an odd number of neutrons: the first four odd-odd nuclides 21H, 63Li, 105B, and 147N (where changing a proton to a neutron or vice versa would lead to a very lopsided proton-neutron ratio) and 180m73Ta, which has not yet been observed to decay despite experimental attempts[6]. Also, four long-lived radioactive odd-odd nuclides (4019K, 5023V, 13857La, 17671Lu) occur naturally.

Of these 9 primordial odd-odd nuclides, only 147N is the most common isotope of a common element, because it is a part of the CNO cycle; 63Li and 105B are minority isotopes of elements that are rare compared to other light elements, while the other six isotopes make up only a tiny percentage of their elements.

Few odd-odd nuclides (and none of the primordial ones) have spin 0 in the ground state.

Odd mass number

There is only one beta-stable nuclide per odd mass number because there is no difference in binding energy between even-odd and odd-even comparable to that between even-even and odd-odd, and other nuclides of the same mass are free to beta decay towards the lowest-energy one. For mass numbers 5, 147, 151, and 209 and up, the one beta-stable isobar is able to alpha decay, so that there are no stable isotopes with these mass numbers. This gives a total of 101 stable isotopes with odd mass numbers.

Odd-mass-number nuclides have half-integer spin and are fermions.

Odd proton-even neutron

These form most of the stable isotopes of the odd-numbered elements, but there is only one stable odd-even isotope for each of the 41 odd-numbered elements from 1 to 81, except for technetium (43Tc) and promethium (61Pm) that have no stable isotopes, and chlorine (17Cl), potassium (19K), copper (29Cu), gallium (31Ga), bromine (35Br), silver (47Ag), antimony (51Sb), iridium (Ir), and thallium (81Tl), each of which has two, making a total of 48 stable odd-even isotopes. There are also four primordial long-lived odd-even isotopes, 8737Rb, 11549In, 15163Eu, and 18775Re.

Even proton-odd neutron

There are 54 stable isotopes that have an even number of protons and an odd number of neutrons. There are also four primordial long lived even-odd isotopes, 11348Cd (beta decay, half-life is 7.7 × 1015 years); 14762Sm (1.06 × 1011a); and 14962Sm (>2 × 1015a); and the fissile 23592U.

The only even-odd isotopes that are the most common one for their element are 19578Pt and 94Be. Beryllium-9 is the only stable beryllium isotope because the expected beryllium-8 has higher energy than two alpha particles and therefore decays to them.

Odd neutron number

| n | E | O |

|---|---|---|

| Stable | 188 | 58 |

| Longlived | 20 | 6 |

| Primordial | 208 | 64 |

The only odd-neutron-number isotopes that are the most common isotope of their element are 19578Pt, 94Be and 147N.

Actinides with odd neutron number are generally fissile, while those with even neutron number are generally not, though they are split when bombarded with fast neutrons.

Occurrence in nature

Elements are composed of one or more naturally occurring isotopes. The unstable (radioactive) isotopes are either primordial, in which case they have persisted down to the present because their rate of decay is so slow (e.g., uranium-238 and potassium-40), or they are postprimordial, created by cosmic ray bombardment as cosmogenic nuclides (e.g., tritium, carbon-14) or by the decay of a radioactive primordial isotope to a radioactive radiogenic nuclide daughter (e.g., uranium to radium).

As discussed above, only 80 elements have any stable isotopes, and 26 of these have only one stable isotope. Thus, about two thirds of stable elements occur naturally on Earth in multiple stable isotopes, with the largest number of stable isotopes for an element being ten, for tin (50Sn). There are about 94 elements found naturally on Earth (up to plutonium inclusive), though some are detected only in very tiny amounts, such as plutonium-244. Scientists estimate that the elements that occur naturally on Earth (some only as radioisotopes) occur as 339 isotopes (nuclides) in total.[7] Only 257 of these naturally occurring isotopes are stable in the sense of either never having been observed to decay as of the present time (227 nuclides), or having been observed to decay but with a half life too long to estimate (30 nuclides). An additional 31 primordial nuclides (to a total of 288 primordial nuclides), are radioactive with known half lives, but have half lives longer than 80 million years, allowing them to exist from the beginning of the solar system. See list of nuclides for details.

All the known stable isotopes occur naturally on Earth; the other naturally occurring-isotopes are radioactive but occur on Earth due to their relatively long half-lives, or else due to other means of ongoing natural production. These include the afore-mentioned cosmogenic nuclides and the short-lived radioisotopes formed by decay of a primordial radioactive isotope, such as radon and radium from uranium.

An additional ~3000 radioactive isotopes not found in nature have been created in nuclear reactors and in particle accelerators. Many short-lived isotopes not found naturally on Earth have also been observed by spectroscopic analysis, being naturally created in stars or supernovae. An example is aluminum-26, which is not naturally found on Earth, but which is found in abundance on an astronomical scale.

The tabulated atomic masses of elements are averages that account for the presence of multiple isotopes with different masses. Before the discovery of isotopes, empirically determined noninteger values of atomic mass confounded scientists. For example, a sample of chlorine contains 75.8% chlorine-35 and 24.2% chlorine-37, giving an average atomic mass of 35.5 atomic mass units.

According to generally accepted cosmology theory, only isotopes of hydrogen and helium, and traces of some isotopes of lithium and beryllium were created at the Big Bang, while all other isotopes were synthesized later, in stars and supernovae, and in interactions between energetic particles such as cosmic rays, and previously produced isotopes. (See nucleosynthesis for details of the various processes thought to be responsible for isotope production.) The respective abundances of isotopes on Earth result from the quantities formed by these processes, their spread through the galaxy, and the rates of decay for isotopes that are unstable. After the initial coalescence of the solar system, isotopes were redistributed according to mass, and the isotopic composition of elements varies slightly from planet to planet. This sometimes makes it possible to trace the origin of meteorites.

Atomic mass of isotopes

The atomic mass (mr) of an isotope is determined mainly by its mass number (i.e. number of nucleons in its nucleus). Small corrections are due to the binding energy of the nucleus (see mass defect), the slight difference in mass between proton and neutron, and the mass of the electrons associated with the atom, the latter because the electron:nucleon ratio differs among isotopes.

The mass number is a dimensionless quantity. The atomic mass, on the other hand, is measured using the atomic mass unit based on the mass of the carbon atom. It is denoted with symbols "u" (for unit) or "Da" (for Dalton).

The atomic masses of naturally occurring isotopes of an element determine the atomic weight of the element. When the element contains N isotopes, the equation below is applied for the atomic weight M:

where m1, m2, ..., mN are the atomic masses of each individual isotope, and x1, ... , xN are the relative abundances of these isotopes.

Applications of isotopes

Several applications exist that capitalize on properties of the various isotopes of a given element. Isotope separation is a significant technological challenge, particularly with heavy elements such as uranium or plutonium. Lighter elements such as lithium, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen are commonly separated by gas diffusion of their compounds such as CO and NO. The separation of hydrogen and deuterium is unusual since it is based on chemical rather than physical properties, for example in the Girdler sulfide process. Uranium isotopes have been separated in bulk by gas diffusion, gas centrifugation, laser ionization separation, and (in the Manhattan Project) by a type of production mass spectroscopy.

Use of chemical and biological properties

- Isotope analysis is the determination of isotopic signature, the relative abundances of isotopes of a given element in a particular sample. For biogenic substances in particular, significant variations of isotopes of C, N and O can occur. Analysis of such variations has a wide range of applications, such as the detection of adulteration of food products.[8] The identification of certain meteorites as having originated on Mars is based in part upon the isotopic signature of trace gases contained in them.[9]

- Another common application is isotopic labeling, the use of unusual isotopes as tracers or markers in chemical reactions. Normally, atoms of a given element are indistinguishable from each other. However, by using isotopes of different masses, they can be distinguished by mass spectrometry or infrared spectroscopy. For example, in 'stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC)' stable isotopes are used to quantify proteins. If radioactive isotopes are used, they can be detected by the radiation they emit (this is called radioisotopic labeling).

- A technique similar to radioisotopic labeling is radiometric dating: using the known half-life of an unstable element, one can calculate the amount of time that has elapsed since a known level of isotope existed. The most widely known example is radiocarbon dating used to determine the age of carbonaceous materials.

- Isotopic substitution can be used to determine the mechanism of a reaction via the kinetic isotope effect.

Use of nuclear properties

- Several forms of spectroscopy rely on the unique nuclear properties of specific isotopes. For example, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy can be used only for isotopes with a nonzero nuclear spin. The most common isotopes used with NMR spectroscopy are 1H, 2D,15N, 13C, and 31P.

- Mössbauer spectroscopy also relies on the nuclear transitions of specific isotopes, such as 57Fe.

- Radionuclides also have important uses. Nuclear power and nuclear weapons development require relatively large quantities of specific isotopes.

See also

- Atom

- Table of nuclides

- Radionuclide (or radioisotope)

- Nuclear medicine (includes medical isotopes)

- Isotopomer

- List of particles

- Isotopes are nuclides having the same number of protons; compare:

- Isotones are nuclides having the same number of neutrons.

- Isobars are nuclides having the same mass number, i.e. sum of protons plus neutrons.

- Nuclear isomers are different excited states of the same type of nucleus. A transition from one isomer to another is accompanied by emission or absorption of a gamma ray, or the process of internal conversion. (Not to be confused with chemical isomers.)

- Bainbridge mass spectrometer

References

- ↑ IUPAC http://goldbook.iupac.org/I03331.html

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Radioactives Missing From The Earth". http://www.don-lindsay-archive.org/creation/isotope_list.html.

- ↑ "NuDat 2 Description". http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/nudat2/help/index.jsp.

- ↑ Budzikiewicz H, Grigsby RD (2006). "Mass spectrometry and isotopes: a century of research and discussion". Mass spectrometry reviews 25 (1): 146–57. doi:10.1002/mas.20061. PMID 16134128.

- ↑ Sonzogni, Alejandro. "Interactive Chart of Nuclides". National Nuclear Data Center: Brook haven National Laboratory. http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/chart/.

- ↑ hhttp://bryza.if.uj.edu.pl/zdfk/wp-includes/publications/misiaszek_180mTa_2009.pdf Search for the radioactivity of 180mTa using an underground HPGe sandwich spectrometer, 2009

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ E. Jamin et al. (2003). "Improved Detection of Added Water in Orange Juice by Simultaneous Determination of the Oxygen-18/Oxygen-16 Isotope Ratios of Water and Ethanol Derived from Sugars"". J. Agric. Food Chem. 51: 5202. doi:10.1021/jf030167 m. http://pubs.acs.org/cgi-bin/article.cgi/jafcau/2003/51/i18/pdf/jf030167 m.pdf.

- ↑ A. H. Treiman, J. D. Gleason and D. D. Bogard (2000). ""The SNC meteorites are from Mars"". Planet. Space. Sci. 48: 1213. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(00)00105-7. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6V6T-41WBDHD-8&_user=2400262&_coverDate=10%2F31%2F2000&_alid=678948366&_rdoc=3&_fmt=summary&_orig=search&_cdi=5823&_sort=r&_docanchor=&view=c&_ct=89&_acct=C000057185&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=2400262&md5=c5ae2aa8ea60dbd76c2870048730a299.

External links

- Nucleonica Nuclear Science Portal

- Nucleonica Nuclear Science Wiki

- International Atomic Energy Agency

- Atomic weights of all isotopes

- Atomgewichte, Zerfallsenergien und Halbwertszeiten aller Isotope

- Chart of the Nuclides produced by the Knolls Atomic Power Laboratory $25

- Exploring the Table of the Isotopes at the LBNL

- Current isotope research and information

- Radioactive Isotopes by the CDC

- Interacive Chart of the nuclides, isotopes and Periodic Table

The LIVEChart of Nuclides - IAEA with isotope data, in Java or HTML

The LIVEChart of Nuclides - IAEA with isotope data, in Java or HTML