Triangle

| Triangle | |

|---|---|

A triangle |

|

| Edges and vertices | 3 |

| Schläfli symbol | {3} |

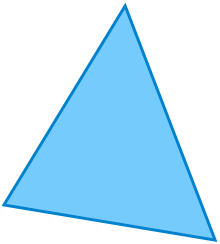

A triangle is one of the basic shapes of geometry: a polygon with three corners or vertices and three sides or edges which are line segments. A triangle with vertices A, B, and C is denoted  ABC.

ABC.

In Euclidean geometry any three non-collinear points determine a unique triangle and a unique plane (i.e. a two-dimensional Euclidean space).

Contents |

Types of triangles

By relative lengths of sides

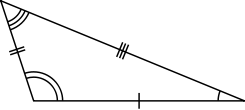

Triangles can be classified according to the relative lengths of their sides:

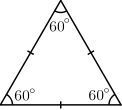

- In an equilateral triangle all sides have the same length. An equilateral triangle is also a regular polygon with all angles measuring 60°.[1]

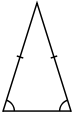

- In an isosceles triangle, two sides are equal in length.[2] An isosceles triangle also has two angles of the same measure; namely, the angles opposite to the two sides of the same length; this fact is the content of the Isosceles triangle theorem. Some mathematicians define an isosceles triangle to have exactly two equal sides, whereas others define an isosceles triangle as one with at least two equal sides.[3] The latter definition would make all equilateral triangles isosceles triangles.

- In a scalene triangle, all sides are unequal.[4] The three angles are also all different in measure. Notice that a scalene triangle can be (but need not be) a right triangle.

.

|

|

|

| Equilateral | Isosceles | Scalene |

By internal angles

Triangles can also be classified according to their internal angles, measured here in degrees.

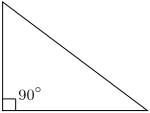

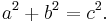

- A right triangle (or right-angled triangle, formerly called a rectangled triangle) has one of its interior angles measuring 90° (a right angle). The side opposite to the right angle is the hypotenuse; it is the longest side of the right triangle. The other two sides are called the legs or catheti[5] (singular: cathetus) of the triangle. Right triangles obey the Pythagorean theorem: the sum of the squares of the lengths of the two legs is equal to the square of the length of the hypotenuse: a2 + b2 = c2, where a and b are the lengths of the legs and c is the length of the hypotenuse. Special right triangles are right triangles with additional properties that make calculations involving them easier. The most famous is the 3-4-5 right triangle, where 32 + 42 = 52. In this situation, 3, 4, and 5 are a Pythagorean Triple.

- Triangles that do not have an angle that measures 90° are called oblique triangles.

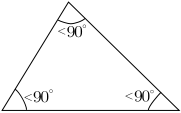

- A triangle that has all interior angles measuring less than 90° is an acute triangle or acute-angled triangle.

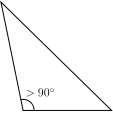

- A triangle that has one angle that measures more than 90° is an obtuse triangle or obtuse-angled triangle.

- A "triangle" with an interior angle of 180° (and collinear vertices) is degenerate.

A triangle that has two angles with the same measure also has two sides with the same length, and therefore it is an isosceles triangle. It follows that in a triangle where all angles have the same measure, all three sides have the same length, and therefore such triangle is equilateral.

|

|

|

| Right | Obtuse | Acute |

|

||

| Oblique | ||

Basic facts

Triangles are assumed to be two-dimensional plane figures, unless the context provides otherwise (see Non-planar triangles, below). In rigorous treatments, a triangle is therefore called a 2-simplex (see also Polytope). Elementary facts about triangles were presented by Euclid in books 1–4 of his Elements, around 300 BC.

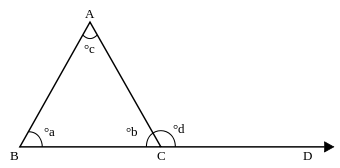

The measures of the interior angles of a triangle in Euclidean space always add up to 180 degrees.[6] This allows determination of the measure of the third angle of any triangle given the measure of two angles. An exterior angle of a triangle is an angle that is a linear pair (and hence supplementary) to an interior angle. The measure of an exterior angle of a triangle is equal to the sum of the measures of the two interior angles that are not adjacent to it; this is the exterior angle theorem. The sum of the measures of the three exterior angles (one for each vertex) of any triangle is 360 degrees.[7]

The sum of the lengths of any two sides of a triangle always exceeds the length of the third side, a principle known as the triangle inequality. Since the vertices of a triangle are assumed to be non-collinear, it is not possible for the sum of the length of two sides be equal to the length of the third side.

Two triangles are said to be similar if every angle of one triangle has the same measure as the corresponding angle in the other triangle. The corresponding sides of similar triangles have lengths that are in the same proportion, and this property is also sufficient to establish similarity.

A few basic theorems about similar triangles:

- If two corresponding internal angles of two triangles have the same measure, the triangles are similar.

- If two corresponding sides of two triangles are in proportion, and their included angles have the same measure, then the triangles are similar. (The included angle for any two sides of a polygon is the internal angle between those two sides.)

- If three corresponding sides of two triangles are in proportion, then the triangles are similar.[8]

Two triangles that are congruent have exactly the same size and shape:[9] all pairs of corresponding interior angles are equal in measure, and all pairs of corresponding sides have the same length. (This is a total of six equalities, but three are often sufficient to prove congruence.)

Some sufficient conditions for a pair of triangles to be congruent are:

- SAS Postulate: Two sides in a triangle have the same length as two sides in the other triangle, and the included angles have the same measure.

- ASA: Two interior angles and the included side in a triangle have the same measure and length, respectively, as those in the other triangle. (The included side for a pair of angles is the side that is common to them.)

- SSS: Each side of a triangle has the same length as a corresponding side of the other triangle.

- AAS: Two angles and a corresponding (non-included) side in a triangle have the same measure and length, respectively, as those in the other triangle.

- Hypotenuse-Leg (HL) Theorem: The hypotenuse and a leg in a right triangle have the same length as those in another right triangle. This is also called RHS (right-angle, hypotenuse, side).

- Hypotenuse-Angle Theorem: The hypotenuse and an acute angle in one right triangle have the same length and measure, respectively, as those in the other right triangle. This is just a particular case of the AAS theorem.

An important case:

- Side-Side-Angle (or Angle-Side-Side) condition: If two sides and a corresponding non-included angle of a triangle have the same length and measure, respectively, as those in another triangle, then this is not sufficient to prove congruence; but if the angle given is opposite to the longer side of the two sides, then the triangles are congruent. The Hypotenuse-Leg Theorem is a particular case of this criterion. The Side-Side-Angle condition does not by itself guarantee that the triangles are congruent because one triangle could be obtuse-angled and the other acute-angled.

Using right triangles and the concept of similarity, the trigonometric functions sine and cosine can be defined. These are functions of an angle which are investigated in trigonometry.

A central theorem is the Pythagorean theorem, which states in any right triangle, the square of the length of the hypotenuse equals the sum of the squares of the lengths of the two other sides. If the hypotenuse has length c, and the legs have lengths a and b, then the theorem states that

The converse is true: if the lengths of the sides of a triangle satisfy the above equation, then the triangle has a right angle opposite side c.

Some other facts about right triangles:

- The acute angles of a right triangle are complementary.

- If the legs of a right triangle have the same length, then the angles opposite those legs have the same measure. Since these angles are complementary, it follows that each measures 45 degrees. By the Pythagorean theorem, the length of the hypotenuse is the length of a leg times √2.

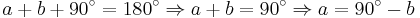

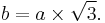

- In a right triangle with acute angles measuring 30 and 60 degrees, the hypotenuse is twice the length of the shorter side, and the longer side is equal to the length of the shorter side times √3 :

For all triangles, angles and sides are related by the law of cosines and law of sines (also called the cosine rule and sine rule).

Points, lines and circles associated with a triangle

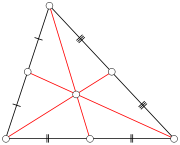

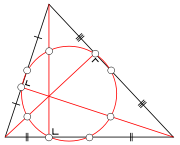

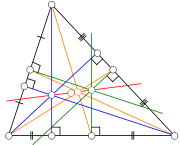

There are hundreds of different constructions that find a special point associated with (and often inside) a triangle, satisfying some unique property: see the references section for a catalogue of them. Often they are constructed by finding three lines associated in a symmetrical way with the three sides (or vertices) and then proving that the three lines meet in a single point: an important tool for proving the existence of these is Ceva's theorem, which gives a criterion for determining when three such lines are concurrent. Similarly, lines associated with a triangle are often constructed by proving that three symmetrically constructed points are collinear: here Menelaus' theorem gives a useful general criterion. In this section just a few of the most commonly encountered constructions are explained.

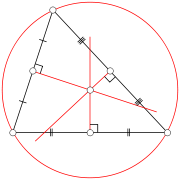

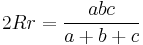

A perpendicular bisector of a side of a triangle is a straight line passing through the midpoint of the side and being perpendicular to it, i.e. forming a right angle with it. The three perpendicular bisectors meet in a single point, the triangle's circumcenter; this point is the center of the circumcircle, the circle passing through all three vertices. The diameter of this circle can be found from the law of sines stated above.

Thales' theorem implies that if the circumcenter is located on one side of the triangle, then the opposite angle is a right one. If the circumcenter is located inside the triangle, then the triangle is acute; if the circumcenter is located outside the triangle, then the triangle is obtuse.

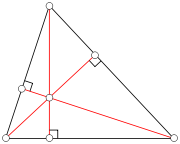

An altitude of a triangle is a straight line through a vertex and perpendicular to (i.e. forming a right angle with) the opposite side. This opposite side is called the base of the altitude, and the point where the altitude intersects the base (or its extension) is called the foot of the altitude. The length of the altitude is the distance between the base and the vertex. The three altitudes intersect in a single point, called the orthocenter of the triangle. The orthocenter lies inside the triangle if and only if the triangle is acute.

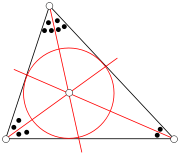

An angle bisector of a triangle is a straight line through a vertex which cuts the corresponding angle in half. The three angle bisectors intersect in a single point, the incenter, the center of the triangle's incircle. The incircle is the circle which lies inside the triangle and touches all three sides. There are three other important circles, the excircles; they lie outside the triangle and touch one side as well as the extensions of the other two. The centers of the in- and excircles form an orthocentric system.

A median of a triangle is a straight line through a vertex and the midpoint of the opposite side, and divides the triangle into two equal areas. The three medians intersect in a single point, the triangle's centroid or geometric barycenter. The centroid of a rigid triangular object (cut out of a thin sheet of uniform density) is also its center of mass: the object can be balanced on its centroid in a uniform gravitational field. The centroid cuts every median in the ratio 2:1, i.e. the distance between a vertex and the centroid is twice the distance between the centroid and the midpoint of the opposite side.

The midpoints of the three sides and the feet of the three altitudes all lie on a single circle, the triangle's nine-point circle. The remaining three points for which it is named are the midpoints of the portion of altitude between the vertices and the orthocenter. The radius of the nine-point circle is half that of the circumcircle. It touches the incircle (at the Feuerbach point) and the three excircles.

The centroid (yellow), orthocenter (blue), circumcenter (green) and center of the nine-point circle (red point) all lie on a single line, known as Euler's line (red line). The center of the nine-point circle lies at the midpoint between the orthocenter and the circumcenter, and the distance between the centroid and the circumcenter is half that between the centroid and the orthocenter.

The center of the incircle is not in general located on Euler's line.

If one reflects a median at the angle bisector that passes through the same vertex, one obtains a symmedian. The three symmedians intersect in a single point, the symmedian point of the triangle.

Computing the area of a triangle

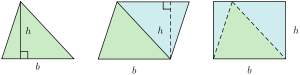

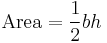

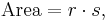

Calculating the area of a triangle is an elementary problem encountered often in many different situations. The best known and simplest formula is:

where b is the length of the base of the triangle, and h is the height or altitude of the triangle. The term 'base' denotes any side, and 'height' denotes the length of a perpendicular from the vertex opposite the side onto the line containing the side itself.

Although simple, this formula is only useful if the height can be readily found. For example, the surveyor of a triangular field measures the length of each side, and can find the area from his results without having to construct a 'height'. Various methods may be used in practice, depending on what is known about the triangle. The following is a selection of frequently used formulae for the area of a triangle.[10]

Using vectors

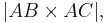

The area of a parallelogram embedded in a three-dimensional Euclidean space can be calculated using vectors. Let vectors AB and AC point respectively from A to B and from A to C. The area of parallelogram ABDC is then

which is the magnitude of the cross product of vectors AB and AC. The area of triangle ABC is half of this,

.

.

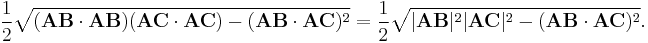

The area of triangle ABC can also be expressed in terms of dot products as follows:

In two-dimensional Euclidean space, expressing vector AB as a free vector in Cartesian space equal to (x1,y1) and AC as (x2,y2), this can be rewritten as:

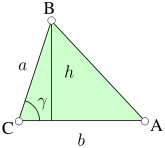

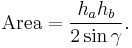

Using trigonometry

The height of a triangle can be found through the application of trigonometry.

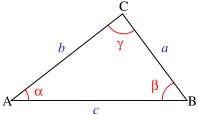

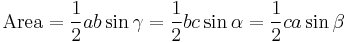

Knowing SAS: Using the labels in the image on the left, the altitude is h = a sin  . Substituting this in the formula Area = ½bh derived above, the area of the triangle can be expressed as:

. Substituting this in the formula Area = ½bh derived above, the area of the triangle can be expressed as:

(where α is the interior angle at A, β is the interior angle at B, γ is the interior angle at C and c is the line AB).

Furthermore, since sin α = sin (π - α) = sin (β + γ), and similarly for the other two angles:

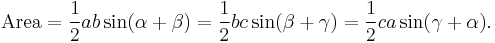

Knowing AAS:

and analogously if the known side is a or c.

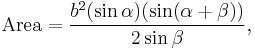

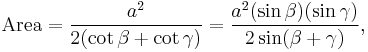

Knowing ASA:[11]

and analogously if the known side is b or c.

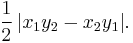

Using coordinates

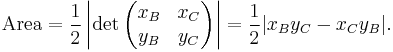

If vertex A is located at the origin (0, 0) of a Cartesian coordinate system and the coordinates of the other two vertices are given by B = (xB, yB) and C = (xC, yC), then the area can be computed as ½ times the absolute value of the determinant

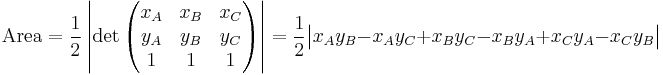

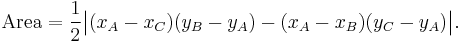

For three general vertices, the equation is:

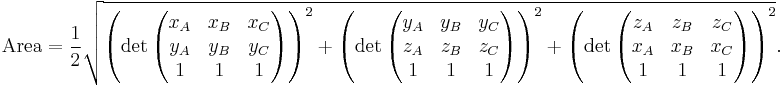

In three dimensions, the area of a general triangle {A = (xA, yA, zA), B = (xB, yB, zB) and C = (xC, yC, zC)} is the Pythagorean sum of the areas of the respective projections on the three principal planes (i.e. x = 0, y = 0 and z = 0):

Using line integrals

The area within any closed curve, such as a triangle, is given by the line integral around the curve of the algebraic or signed distance of a point on the curve from an arbitrary oriented straight line L. Points to the right of L as oriented are taken to be at negative distance from L, while the weight for the integral is taken to be the component of arc length parallel to L rather than arc length itself.

This method is well suited to computation of the area of an arbitrary polygon. Taking L to be the x-axis, the line integral between consecutive vertices (xi,yi) and (xi+1,yi+1) is given by the base times the mean height, namely (xi+1 − xi)(yi + yi+1)/2. The sign of the area is an overall indicator of the direction of traversal, with negative area indicating counterclockwise traversal. The area of a triangle then falls out as the case of a polygon with three sides.

While the line integral method has in common with other coordinate-based methods the arbitrary choice of a coordinate system, unlike the others it makes no arbitrary choice of vertex of the triangle as origin or of side as base. Furthermore the choice of coordinate system defined by L commits to only two degrees of freedom rather than the usual three, since the weight is a local distance (e.g. xi+1 − xi in the above) whence the method does not require choosing an axis normal to L.

When working in polar coordinates it is not necessary to convert to cartesian coordinates to use line integration, since the line integral between consecutive vertices (ri,θi) and (ri+1,θi+1) of a polygon is given directly by riri+1sin(θi+1 − θi)/2. This is valid for all values of θ, with some decrease in numerical accuracy for sufficiently large multiples of π. With this formulation negative area indicates clockwise traversal, which should be kept in mind when mixing polar and cartesian coordinates. Just as the choice of y-axis (x = 0) is immaterial for line integration in cartesian coordinates, so is the choice of zero heading (θ = 0) immaterial here.

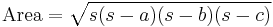

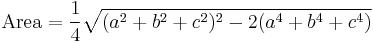

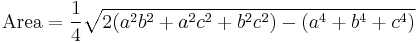

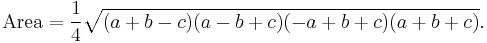

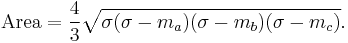

Using Heron's formula

The shape of the triangle is determined by the lengths of the sides alone. Therefore the area can also be derived from the lengths of the sides. By Heron's formula:

where  is the semiperimeter, or half of the triangle's perimeter.

is the semiperimeter, or half of the triangle's perimeter.

Three equivalent ways of writing Heron's formula are

Formulas mimicking Heron's formula

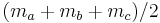

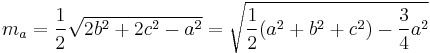

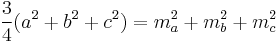

Three formulas have the same structure as Heron's formula but are expressed in terms of different variables. First, denoting the medians from sides a, b, and c respectively as  and

and  and their semi-sum

and their semi-sum  as

as  , we have[12]

, we have[12]

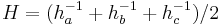

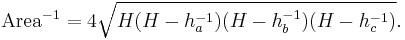

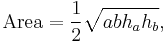

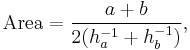

Next, denoting the altitudes from sides a, b, and c respectively as  ,

,  , and

, and  ,and denoting the semi-sum of the reciprocals of the altitudes as

,and denoting the semi-sum of the reciprocals of the altitudes as  we have[13]

we have[13]

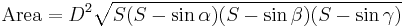

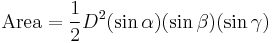

And denoting the semi-sum of the angles' sines as ![S=[(\sin \ \ \alpha)+(\sin \ \ \beta)+(\sin \ \ \gamma)]/2](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/8999d32a9a96b92f28619cfa2c8928c2.png) , we have [14]

, we have [14]

where D is the diameter of the circumcircle:

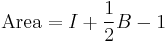

Using Pick's Theorem

See Pick's theorem for a technique for finding the area of any arbitrary lattice polygon.

The theorem states:

where I is the number of internal lattice points and B is the number of lattice points lying inline with the border of the polygon.

Other area formulas

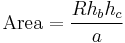

Numerous other area formulas exist, such as

where r is the inradius, and s is the semiperimeter;

for circumdiameter D; and[15]

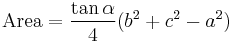

for angle  90°.

90°.

In 1885, Baker[16]gave a collection of over a hundred distinct area formulas for the triangle (although the reader should be advised that a few of them are incorrect). These include #9, #39a, #39b, #42, and #49:

for circumradius (radius of the circumcircle) R, and

Computing the sides and angles

In general, there are various accepted methods of calculating the length of a side or the size of an angle. Whilst certain methods may be suited to calculating values of a right-angled triangle, others may be required in more complex situations.

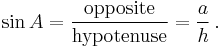

Trigonometric ratios in right triangles

In right triangles, the trigonometric ratios of sine, cosine and tangent can be used to find unknown angles and the lengths of unknown sides. The sides of the triangle are known as follows:

- The hypotenuse is the side opposite the right angle, or defined as the longest side of a right-angled triangle, in this case h.

- The opposite side is the side opposite to the angle we are interested in, in this case a.

- The adjacent side is the side that is in contact with the angle we are interested in and the right angle, hence its name. In this case the adjacent side is b.

Sine, cosine and tangent

The sine of an angle is the ratio of the length of the opposite side to the length of the hypotenuse. In our case

Note that this ratio does not depend on the particular right triangle chosen, as long as it contains the angle A, since all those triangles are similar.

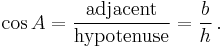

The cosine of an angle is the ratio of the length of the adjacent side to the length of the hypotenuse. In our case

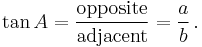

The tangent of an angle is the ratio of the length of the opposite side to the length of the adjacent side. In our case

The acronym "SOH-CAH-TOA" is a useful mnemonic for these ratios.

Inverse functions

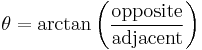

The inverse trigonometric functions can be used to calculate the internal angles for a right angled triangle with the length of any two sides.

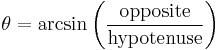

Arcsin can be used to calculate an angle from the length of the opposite side and the length of the hypotenuse.

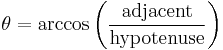

Arccos can be used to calculate an angle from the length of the adjacent side and the length of the hypontenuse.

Arctan can be used to calculate an angle from the length of the opposite side and the length of the adjacent side.

In introductory geometry and trigonometry courses, the notation sin−1, cos−1, etc., are often used in place of arcsin, arccos, etc. However, the arcsin, arccos, etc., notation is standard in higher mathematics where trigonometric functions are commonly raised to powers, as this avoids confusion between multiplicative inverse and compositional inverse.

The sine, cosine and tangent rules

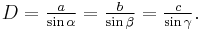

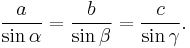

The law of sines, or sine rule,[17] states that the ratio of the length of a side to the sine of its corresponding opposite angle is constant, that is

This ratio is equal to the diameter of the circumscribed circle of the given triangle. Another interpretation of this theorem is that every triangle with angles  ,

,  and

and  is similar to a triangle with side lengths equal to

is similar to a triangle with side lengths equal to  ,

,  and

and  . This triangle can be constructed by first constructing a circle of diameter 1, and inscribing in it two of the angles of the triangle. The length of the sides of that triangle will be

. This triangle can be constructed by first constructing a circle of diameter 1, and inscribing in it two of the angles of the triangle. The length of the sides of that triangle will be  ,

,  and

and  . The side whose length is

. The side whose length is  is opposite to the angle whose measure is

is opposite to the angle whose measure is  , etc.

, etc.

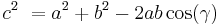

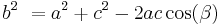

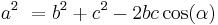

The law of cosines, or cosine rule, connects the length of an unknown side of a triangle to the length of the other sides and the angle opposite to the unknown side. As per the law:

For a triangle with length of sides  ,

,  ,

,  and angles of

and angles of  ,

,  ,

,  respectively, given two known lengths of a triangle

respectively, given two known lengths of a triangle  and

and  , and the angle between the two known sides

, and the angle between the two known sides  (or the angle opposite to the unknown side

(or the angle opposite to the unknown side  ), to calculate the third side

), to calculate the third side  , the following formula can be used:

, the following formula can be used:

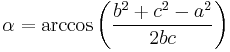

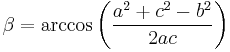

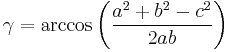

If the lengths of all three sides of any triangle are known the three angles can be calculated:

The law of tangents or tangent rule, is less known than the other two. It states that:

It is not used very often, but can be used to find a side or an angle when you know two sides and an angle or two angles and a side.

Further formulas for general Euclidean triangles

The following formulas are also true for all Euclidean triangles:

and

,

,

and equivalently for  and

and  , relating the medians and the sides;

, relating the medians and the sides;

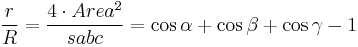

for semiperimeter s, where the bisector length is measured from the vertex to where it meets the opposite side; and the following formulas involving the circumradius R and the inradius r:

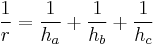

in terms of the altitudes,

,

,

and

.

.

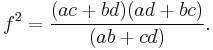

Suppose two adjacent but non-overlapping triangles share the same side of length f and share the same circumcircle, so that the side of length f is a chord of the circumcircle and the triangles have side lengths (a, b, f) and (c, d, f), with the two triangles together forming a cyclic quadrilateral with side lengths in sequence (a, b, c, d). Then[18]:84

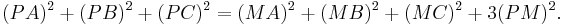

Let M be the centroid of a triangle with vertices A, B, and C, and let P be any interior point. Then the distances between the points are related by[18]:174

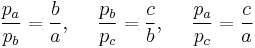

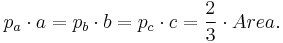

Let pa, pb, and pc be the distances from the centroid to the sides of lengths a, b, and c. Then[18]:173

and

Non-planar triangles

A non-planar triangle is a triangle which is not contained in a (flat) plane. Examples of non-planar triangles in non-Euclidean geometries are spherical triangles in spherical geometry and hyperbolic triangles in hyperbolic geometry.

While the measures of the internal angles in planar triangles always sum to 180°, a hyperbolic triangle has measures of angles that sum to less than 180°, and a spherical triangle has measures of angles that sum to more than 180°. A hyperbolic triangle can be obtained by drawing on a negatively curved surface, such as a saddle surface, and a spherical triangle can be obtained by drawing on a positively curved surface such as a sphere. Thus, if one draws a giant triangle on the surface of the Earth, one will find that the sum of the measures of its angles is greater than 180°; in fact it will be between 180° and 540°[19]. In particular it is possible to draw a triangle on a sphere such that the measure of each of its internal angles is equal to 90°, adding up to a total of 270°.

Specifically, on a sphere the sum of the angles of a triangle is

- 180°×(1+4f ),

where f is the fraction of the sphere's area which is enclosed by the triangle. For example, suppose that we draw a triangle on the Earth's surface with vertices at the North Pole, at a point on the equator at 0° longitude, and a point on the equator at 90° West longitude. The great circle line between the latter two points is the equator, and the great circle line between either of those points and the North Pole is a line of longitude; so there are right angles at the two points on the equator. Moreover, the angle at the North Pole is also 90° because the other two vertices differ by 90° of longitude. So the sum of the angles in this triangle is 90°+90°+90°=270°. The triangle encloses 1/4 of the northern hemisphere (90°/360° as viewed from the North Pole) and therefore 1/8 of the Earth's surface, so in the formula f = 1/8; thus the formula correctly gives the sum of the triangle's angles as 270°.

From the above angle sum formula we can also see that the Earth's surface is locally flat: If we draw an arbitrarily small triangle in the neighborhood of one point on the Earth's surface, the fraction f of the Earth's surface which is enclosed by the triangle will be arbitrarily close to zero. In this case the angle sum formula simplifies to 180°, which we know is what Euclidean geometry tells us for triangles on a flat surface.

See also

- A-frame for hang gliders, trikes, and ultralights

- BAMBI (geometry)

- Congruence (geometry)

- Dragon's Eye (symbol)

- Fermat point

- Hadwiger–Finsler inequality

- Heronian triangle

- Inertia tensor of triangle

- Integer triangle

- Law of cosines

- Law of sines

- Law of tangents

- Lester's theorem

- List of triangle topics

- Ono's inequality

- Pedoe's inequality

- Pythagorean theorem

- Special right triangles

- Triangle center

- Triangular number

- Triangulated category

- Triangulation (topology)

References

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "Equilateral Triangle" from MathWorld.

- ↑ Euclid defines isosceles triangles based on the number of equal sides, i.e. only two equal sides. An alternative approach defines isosceles triangles based on shared properties, i.e. equilateral triangles are a special case of isosceles triangles. Wiktionary definition of isosceles triangle, Weisstein, Eric W., "Isosceles triangle" from MathWorld.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "Isosceles Triangle" from MathWorld.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "Scalene triangle" from MathWorld.

- ↑ Zeidler, Eberhard (2004). Oxford User's Guide to Mathematics. Oxford University Press. p. 729. ISBN 978-0-19-850763-5.

- ↑ Proof in Euclid's Elements (Book I, Proposition 32)

- ↑ The n external angles of any n-sided convex polygon add up to 360 degrees.

- ↑ Again, in all cases "mirror images" are also similar.

- ↑ All pairs of congruent triangles are also similar; but not all pairs of similar triangles are congruent.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "Triangle area" from MathWorld.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric, http://mathworld.wolfram.com/triangle.html

- ↑ Benyi, Arpad, "A Heron-type formula for the triangle," Mathematical Gazette" 87, July 2003, 324-326.

- ↑ Mitchell, Douglas W., "A Heron-type formula for the reciprocal area of a triangle," Mathematical Gazette 89, November 2005, 494.

- ↑ Mitchell, Douglas W., "A Heron-type area formula in terms of sines," Mathematical Gazette 93, March 2009, 108-109.

- ↑ Mitchell, Douglas W., "The area of a quadrilateral," Mathematical Gazette 93, July 2009, 306-309.

- ↑ Baker, Marcus, "A collection of formulae for the area of a plane triangle," Annals of Mathematics, part 1 in vol. 1(6), January 1885, 134-138; part 2 in vol. 2(1), September 1885, 11-18.

- ↑ Prof. David E. Joyce. "The Laws of Cosines and Sines". Clark University. http://www.clarku.edu/~djoyce/trig/laws.html. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Johnson, Roger A., Advanced Euclidean Geometry, Dover Publ. Co., 2007

- ↑ Watkins, Matthew, Useful Mathematical and Physical Formulae, Walker and Co., 2000.

External links

- Area of a triangle - 7 different ways

- Animated demonstrations of triangle constructions using compass and straightedge.

- Basic Overview & Explanation of Triangles

- Computer-Generated Encyclopedia of Euclidean Geometry The first part of the encyclopedia contains more than 3000 computer-generated statements of theorems in Triangle Geometry.

- Clark Kimberling: Encyclopedia of triangle centers. Lists some 3200 interesting points associated with any triangle.

- Christian Obrecht: Eukleides. Software package for creating illustrations of facts about triangles and other theorems in Euclidean geometry.

- Proof that the sum of the angles in a triangle is 180 degrees

- The Triangles Web, by Quim Castellsaguer

- Triangle Calculator - completes triangles when given three elements (sides, angles, area, height etc.), supports degrees, radians and grades.

- Triangle definition pages with interactive applets that are also useful in a classroom setting.

- Triangles at Mathworld

|

|||||||||||||||||

![\mathrm{Area} = \frac{1}{2}[abch_ah_bh_c]^{1/3},](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/b1e08f5390fe05448d8ba3ea3ac1d28d.png)

![\frac{a-b}{a+b} = \frac{\tan[\frac{1}{2}(\alpha-\beta)]}{\tan[\frac{1}{2}(\alpha+\beta)]}.](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/14e5740e715d618d2f6f6f2b3e774900.png)

![\text{Length of the internal bisector of} \ \ \alpha = \frac{2 \sqrt{bcs(s-a)}}{b+c} = \sqrt{bc[1- \frac{a^{2}}{(b+c)^{2}}]}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/2cfba10ab8e26704e3f5bfb331604f45.png)