Indo-Scythians

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Indo-Scythians are a branch of Sakas (Scythians), who migrated from southern Siberia into Bactria, Sogdiana, Arachosia, Gandhara, Kashmir, Punjab, Gujarat, Maharashtra and Rajasthan, from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 4th century CE. The first Saka king in Pakistan and India was Maues or Moga who established Saka power in Gandhara (Pakistan) and gradually extended supremacy over north-western India. Indo-Scythian rule in India ended with the last Western Satrap Rudrasimha III in 395 CE.

The invasion of India by Scythian tribes from Central Asia, often referred to as the Indo-Scythian invasion, played a significant part in the history of India as well as nearby countries. In fact, the Indo-Scythian war is just one chapter in the events triggered by the nomadic flight of Central Asians from conflict with Chinese tribes which had lasting effects on Bactria, Kabol, Parthia and India as well as far off Rome in the west.

The Scythian groups that invaded India and set up various kingdoms, included besides the Sakas other allied tribes, such as the Medii, Xanthii, Massagetae, Getae, Parama Kambojas, Avars, Bahlikas, Rishikas and Paradas.

Origins

The ancestors of the Indo-Scythians are thought to be Sakas (Scythian) tribes, originally settled in southern Siberia, in the Ili river area.

Yuezhi expansion

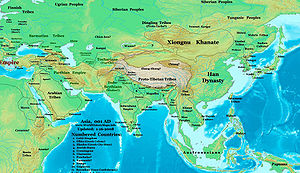

In the 2nd century BCE, a fresh nomadic movement started among the Central Asian tribes, producing lasting effects on the history of Rome in Europe and Bactria, Kabul, Parthia and India in the east. Recorded in the annals of the Han dynasty and other Chinese records, this great tribal movement began after the Yuezhi tribe was defeated by the Xiongnu, fleeing westwards after their defeat and creating a domino effect as they displaced other central Asian tribes in their path.

According to these ancient sources Modu Shanyu of the Xiongnu tribe of Mongolia attacked the Yuezhi and evicted them from their homeland Gansu (Nanshan).[1] Leaving behind a remnant of their number, most of the population moved westwards, and following the route north of the Taklamakan, entered the lands of the Haumavarka Sakas of Issyk Kul Lake through the passes of the Tian Shan. Unable to withstand the assault, the Haumavarka Sakas allowed the Yuezhi to settle in their lands. In the years to come, the Haumavarka Sakas (Sakas of Wusun?) sought the help of the Xiongnu people and evicted the Yuezhi.

Even so, the initial clash with the invading Yuezhi caused a large group of the Haumavarka Sakas to leave their ancestral home. These Sakas journeyed through Tashkent and Ferghana (Sogdiana) (inhabited by the Sugud or Shulik tribe of the Iranians) and occupied the Doab of Oxus and Jaxartes, also overrunning the western parts of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom.[2] Others suggest Tukhara (India and Central Asia, 1955, p 125, P. C. Bagchi). D. C. Sircar reconciles the difference by suggesting that Daxia referred to Tukhara and the eastern parts of Bactria.[3]

After being defeated and evicted by the joint forces of the Wusun and Xiongnu people, the Da Yuezhi also moved southwards, overrunning in their path the Rishikas, Parama-Kambojas, Lohas and other allied Scythian clans living in the Transoxian regions as far as Fargana. Many fled in a southwesterly direction and joined the Haumavarka Sakas in Bactria. The Yuezhi followed behind. Once again under extreme pressure, the Sakas and other allied Scythian groups including the Kambojas were forced to leave Bactria.

They first tried to enter India via the Kabul valley but were vigorously opposed by the Indo-Greek powers there. Rebuffed, the clans turned westwards to Herat and then took a southerly direction, reaching Helmund valley (Sigal) in south-west Afghanistan, the region later called Sakasthan or Seistan. Some scholars believe that this Indo-Scythian migration through Herat to Drangiana was accompanied by groups of Kambojas (Parama-Kambojas), Rishikas and other allied tribes from Transoxiana that were also displaced by the Yuezhi.[4]

Around 175 BCE, the Yuezhi tribes (possibly related to the Tocharians) who lived in eastern Tarim Basin area), were defeated by the Xiongnu tribes, and fled west into the Ili river area. There, they displaced the Sakas, who migrated south into Ferghana and Sogdiana. According to the Chinese historical chronicles (who call the Sakas, "Sai" 塞):

"The Yuezhi attacked the king of the Sai who moved a considerable distance to the south and the Yuezhi then occupied his lands" (Han Shu 61 4B).

Sometime after 155 BCE, the Yuezhi were again defeated by an alliance of the Wusun and the Xiongnu, and were forced to move south, again displacing the Scythians, who migrated south towards Bactria, and south-west towards Parthia and Afghanistan.

The Sakas seem to have entered the territory of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom around 145 BCE, where they burnt to the ground the Greek city of Alexandria on the Oxus. The Yuezhi remained in Sogdiana on the northern bank of the Oxus, but they became suzerains of the Sakas in Bactrian territory, as described by the Chinese ambassador Zhang Qian who visited the region around 126 BCE.

In Parthia, between 138–124 BCE, the Sakas tribes of the Massagetae and Sacaraucae came into conflict with the Parthian Empire, winning several battles, and killing successively King Phraates II and King Artabanus I.

The Parthian king Mithridates II finally retook control of Central Asia, first by defeating the Yuezhi in Sogdiana in 115 BCE, and then defeating the Scythians in Parthia and Seistan around 100 BCE.

After their defeat, the Yuezhi tribes migrated into Bactria, which they were to control for several centuries, and from which they later conquered northern India to found the Kushan Empire. The area of Bactria they settled came to be known as Tocharistan, since the Yuezhi were called Tocharians by the Greeks.

Settlement in Sakastan

The Sakas settled in areas of southern Afghanistan, still called after them Sakastan. From there, they progressively expanded into the Indian subcontinent, where they established various kingdoms, and where they are known as "Indo-Scythians".

The Arsacid emperor Mithridates II (c 123–88/87 BCE) had scored many successes against the Scythians and added many provinces to the Parthian empire,[5] and apparently the Scythian hordes that came from Bactria were also conquered by him. A section of these people moved from Bactria to Lake Helmond in the wake of Yue-chi pressure and settled about Drangiana (Sigal), a region which later came to be called "Sakistana of the Skythian (Scythian) Sakai",[6] towards the end of 1st century BCE.[7] The region is still known as Seistan.

Sakistan or Seistan of Drangiana may not only have been the habitat of the Saka alone but may also have contained population of the Pahlavas and the Kambojas.[8] The Rock Edicts of King Ashoka only refer to the Yavanas, Kambojas and the Gandharas in the northwest, but no mention is made of the Sakas, who immigrated in the region more than a century later. It is thus likely that the immigrant Saka populations who settled in Afghanistan did so among or near the Kambojas and nearby Greek cities.[9] Numerous scholars believe that during centuries immediately preceding Christian era, there had occurred extensive social and cultural admixture among the Kambojas and Yavanas; the Sakas and Pahlavas; and the Kambojas, Sakas, and Pahlavas etc.... such that their cultures and social customs had become almost identical.

The presence of the Sakas in Sakastan in the 1st century BCE is mentioned by Isidore of Charax in his "Parthian stations". He explained that they were bordered at that time by Greek cities to the east (Alexandria of the Caucasus and Alexandria of the Arachosians), and the Parthian-controlled territory of Arachosia to the south:

- "Beyond is Sacastana of the Scythian Sacae, which is also Paraetacena, 63 schoeni. There are the city of Barda and the city of Min and the city of Palacenti and the city of Sigal; in that place is the royal residence of the Sacae; and nearby is the city of Alexandria (Alexandria Arachosia), and six villages." Parthian stations, 18.[10]

Indo-Scythian kingdoms

Abhira to Surastrene

The first Indo-Scythian kingdom in the Indian subcontinent occupied the southern part of Pakistan (which they accessed from southern Afghanistan), in the areas from Abiria (Sindh) to Surastrene (Gujarat), from around 110 to 80 BCE. They progressively further moved north into Indo-Greek territory until the conquests of Maues, c 80 BCE.

The 1st century CE Periplus of the Erythraean Sea describes the Scythian territories there:

- "Beyond this region (Gedrosia), the continent making a wide curve from the east across the depths of the bays, there follows the coast district of Scythia, which lies above toward the north; the whole marshy; from which flows down the river Sinthus, the greatest of all the rivers that flow into the Erythraean Sea, bringing down an enormous volume of water (...) This river has seven mouths, very shallow and marshy, so that they are not navigable, except the one in the middle; at which by the shore, is the market-town, Barbaricum. Before it there lies a small island, and inland behind it is the metropolis of Scythia, Minnagara."[11]

The Indo-Scythians ultimately established a kingdom in the northwest, based in Taxila, with two Great Satraps, one in Mathura in the east, and one in Surastrene (Gujarat) in the southwest.

In the southeast, the Indo-Scythians invaded the area of Ujjain, but were subsequently repelled in 57 BCE by the Malwa king Vikramaditya. To commemorate the event Vikramaditya established the Vikrama era, a specific Indian calendar starting in 57 BCE. More than a century later, in 78 CE the Sakas would again invade Ujjain and establish the Saka era, marking the beginning of the long-lived Saka Western Satraps kingdom.[12]

Gandhara and Punjab

The presence of the Scythians in north-western India during the 1st century BCE was contemporary with that of the Indo-Greek Kingdoms there, and it seems they initially recognized the power of the local Greek rulers.

Maues first conquered Gandhara and Taxila around 80 BCE, but his kingdom disintegrated after his death. In the east, the Indian king Vikrama retook Ujjain from the Indo-Scythians, celebrating his victory by the creation of the Vikrama Era (starting 58 BCE). Indo-Greek kings again ruled after Maues, and prospered, as indicated by the profusion of coins from Kings Apollodotus II and Hippostratos. Not until Azes I, in 55 BCE, did the Indo-Scythians take final control of northwestern India, with his victory over Hippostratos.

Sculpture

Several stone sculptures have been found in the Early Saka layer (Layer No4, corresponding to the period of Azes I, in which numerous coins of the latter were found) in the ruins of Sirkap, during the excavations organized by John Marshall.

Several of them are toilet trays (also called Stone palettes) roughly imitative of earlier, and finer, Hellenistic ones found in the earlier layers. Marshall comments that "we have a praiseworthy effort to copy a Hellenistic original but obviously without the appreciation of form and skill which were necessary for the task". From the same layer, several statuettes in the round are also known, in very rigid and frontal style.

Bimaran casket

Azes is connected to the Bimaran casket, one of the earliest representations of the Buddha. The casket was used for the dedication of a stupa in Bamiran, near Jalalabad in Afghanistan, and placed inside the stupa with several coins of Azes. This event may have happened during the reign of Azes (60–20 BCE), or slightly later. The Indo-Scythians are otherwise connected with Buddhism (see Mathura lion capital), and it is indeed possible they would have commended the work.

Mathura area ("Northern Satraps")

Obv: Bust of King Rajuvula, with Greek legend.

Rev: Pallas standing right (crude). Kharoshthi legend.

In central India, the Indo-Scythians conquered the area of Mathura over Indian kings around 60 BCE. Some of their satraps were Hagamasha and Hagana, who were in turn followed by the Saca Great Satrap Rajuvula.

The Mathura lion capital, an Indo-Scythian sandstone capital in crude style, from Mathura in Central India, and dated to the 1st century CE, describes in kharoshthi the gift of a stupa with a relic of the Buddha, by Queen Nadasi Kasa, the wife of the Indo-Scythian ruler of Mathura, Rajuvula. The capital also mentions the genealogy of several Indo-Scythian satraps of Mathura.

Rajuvula apparently eliminated the last of the Indo-Greek kings Strato II around 10 CE, and took his capital city, Sagala.

The coinage of the period, such as that of Rajuvula, tends to become very crude and barbarized in style. It is also very much debased, the silver content becoming lower and lower, in exchange for a higher proportion of bronze, an alloying technique (billon) suggesting less than wealthy finances.

The Mathura Lion Capital inscriptions attest that Mathura fell under the control of the Sakas. The inscriptions contain references to Kharaosta Kamuio and Aiyasi Kamuia. Yuvaraja Kharostes (Kshatrapa) was the son of Arta as is attested by his own coins.[13] Arta is stated to be brother of King Moga or Maues.[14] Princess Aiyasi Kambojaka, also called Kambojika, was the chief queen of Shaka Mahakshatrapa Rajuvula. Kamboja presence in Mathura is also verified from some verses of epic Mahabharata which are believed to have been composed around this period.[15] This may suggest that Sakas and Kambojas may have jointly ruled over Mathura/Uttara Pradesh. It is revealing that Mahabharata verses only attest the Kambojas and Yavanas as the inhabitants of Mathura, but do not make any reference to the Sakas.[16] Probably, the epic has reckoned the Sakas of Mathura among the Kambojas or else have addressed them as Yavanas, unless the Mahabharata verses refer to the previous period of invasion occupation by the Yavanas around 150 BCE.

The Indo-Scythian satraps of Mathura are sometimes called the "Northern Satraps", in opposition to the "Western Satraps" ruling in Gujarat and Malwa. After Rajuvula, several successors are known to have ruled as vassals to the Kushans, such as the "Great Satrap" Kharapallana and the "Satrap" Vanaspara, who are known from an inscription discovered in Sarnath, and dated to the 3rd year of Kanishka (c 130 CE), in which they were paying allegiance to the Kushans.[17]

Pataliputra

The text of the Yuga Purana describes an invasion of Pataliputra by the Scythians sometimes during the 1st century BCE, after seven great kings had ruled in succession in Saketa following the retreat of the Yavanas. The Yuga Purana explains that the king of the Sakas killed one fourth of the population, before he was himself slain by the Kalinga king Shata and a group of Sabalas (Sabaras).[18]

Kushan and Indo-Parthian conquests

After the death of Azes, the rule of the Indo-Scythians in northwestern India was shattered with the rise of the Indo-Parthian ruler Gondophares in the last years of the 1st century BCE. For the following decades, a number of minor Scythian leaders maintained themselves in local strongholds on the fringes of the loosely assembled Indo-Parthian empire,some of them paying formal allegiance to Gondophares I and his successors.

During the latter part of the 1st century CE, the Indo-Parthian overlordship was gradually replaced with that of the Kushans, one of the five tribes of the Yuezhi who had lived in Bactria for more than a century, and were now expanding into India to create a Kushan Empire. The Kushans ultimately regained northwestern India from around 75 CE, and the area of Mathura from around 100 CE, where they were to prosper for several centuries.

Western Kshatrapas legacy

Indo-Scythians continued to hold the area of Seistan until the reign of Bahram II (276–293 CE), and held several areas of India well into the 1st millennium: Kathiawar and Gujarat were under their rule until the 5th century under the designation of Western Kshatrapas, until they were eventually conquered by the Gupta emperor Chandragupta II (also called Vikramaditya).

The Brihat-Katha-Manjari of the Kshmendra (10/1/285-86) informs us that around 400 CE the Gupta king Vikramaditya (Chandragupta II) had unburdened the sacred earth of the Barbarians like the Shakas, Mlecchas, Kambojas, Yavanas, Tusharas, Parasikas, Hunas, etc. by annihilating these sinners completely.

The 10th century CE Kavyamimamsa of Raj Shekhar (Ch 17) still lists the Shakas, Tusharas, Vokanas, Hunas, Kambojas, Bahlikas, Pahlavas, Tangana, Turukshas, etc. together and states them as the tribes located in the Uttarapatha division.

Indo-Scythian coinage

Indo-Scythian coinage is generally of a high artistic quality, although it clearly deteriorates towards the disintegration of Indo-Scythian rule around 20 CE (coins of Rajuvula). A fairly high-quality but rather stereotypical coinage would continue in the Western Satraps until the 4th century CE.

Indo-Scythian coinage is generally quite realistic, artistically somewhere between Indo-Greek and Kushan coinage. It is often suggested Indo-Scythian coinage benefited from the help of Greek celators (Boppearachchi).

Indo-Scythian coins essentially continue the Indo-Greek tradition, by using the Greek language on the obverse and the Kharoshthi language on the reverse. The portrait of the king is never shown however, and is replaced by depictions of the king on horse (and sometimes on camel), or sometimes sitting cross-legged on a cushion. The reverse of their coins typically show Greek divinities.

Buddhist symbolism is present throughout Indo-Scythian coinage. In particular, they adopted the Indo-Greek practice since Menander I of showing divinities forming the vitarka mudra with their right hand (as for the mudra-forming Zeus on the coins of Maues or Azes II), or the presence of the Buddhist lion on the coins of the same two kings, or the triratana symbol on the coins of Zeionises.

Depiction of Indo-Scythians

Besides coinage, few works of art are known to indisputably represent Indo-Scythians. Indo-Scythians rulers are usually depicted on horseback in armour, but the coins of Azilises show the king in a simple, undecorated, tunic.

Several Gandharan sculptures also show foreigner in soft tunics, sometimes wearing the typical Scythian cap. They stand in contrast to representations of Kushan men, who seem to wear thicks, rigid, tunics, and who are generally represented in a much more simplistic manner.[19]

Buner reliefs

Indo-Scythian soldiers in military attire are sometimes represented in Buddhist friezes in the art of Gandhara (particularly in Buner reliefs). They are depicted in ample tunics with trousers, and have heavy straight sword as a weapon. They wear a pointed hood (the Scythian cap or bashlyk), which distinguishes them from the Indo-Parthians who only wore a simple fillet over their bushy hair,[20] and which is also systematically worn by Indo-Scythian rulers on their coins. With the right hand, some of them are forming the Karana mudra against evil spirits. In Gandhara, such friezes were used as decorations on the pedestals of Buddhist stupas. They are contemporary with other friezes representing people in purely Greek attire, hinting at an intermixing of Indo-Scythians (holding military power) and Indo-Greeks (confined, under Indo-Scythian rule, to civilian life).

Another relief is known where the same type of soldiers are playing musical instruments and dancing, activities which are widely represented elsewhere in Gandharan art: Indo-Scythians are typically shown as reveling devotees.

Indo-Scythians pushing along the Greek god Dyonisos with Ariadne.[21] |

Hunting scene. |

Hunting scene. |

Hunting scene. |

Stone palettes

Numerous stone palettes found in Gandhara are considered as good representatives of Indo-Scythian art. These palettes combine Greek and Iranian influences, and are often realized in a simple, archaic style. Stone palettes have only been found in archaeological layers corresponding to Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian rule, and are essentially unknown the preceding Mauryan layers or the succeeding Kushan layers.[22]

Very often these palettes represent people in Greek dress in mythological scenes, a few in Parthian dress (head-bands over bushy hair, crossed-over jacket on a bare chest, jewelry, belt, baggy trousers), and even fewer in Indo-Scythian dress (Phrygian hat, tunic and comparatively straight trousers). A palette found in Sirkap and now in the New Delhi Museum shows a winged Indo-Scythian horseman riding winged deer, and being attacked by a lion.

The Indo-Scythians and Buddhism

The Indo-Scythians seem to have been followers of Buddhism, and many of their practices apparently continued those of the Indo-Greeks. They are known for their numerous Buddhist dedications, recorded through such epigraphic material as the Taxila copper plate inscription or the Mathura lion capital inscription.

Butkara Stupa

Excavation at the Butkara Stupa in Swat by an Italian archaeological team have yielded various Buddhist sculptures thought to belong to the Indo-Scythian period. In particular, an Indo-Corinthian capital representing a Buddhist devotee within foliage has been found which had a reliquary and coins of Azes buried at its base, securely dating the sculpture to around 20 BCE.[25] A contemporary pilaster with the image of a Buddhist devotee in Greek dress has also been found at the same spot, again suggesting a mingling of the two populations.[26] Various reliefs at the same location show Indo-Scythians with their characteristics tunics and pointed hoods within a Buddhist context, and side-by-side with reliefs of standing Buddhas.[27]

Gandharan sculptures

Other reliefs have been found, which show Indo-Scythian men with their characteristic pointed cap pushing a cart on which is reclining the Greek god Dionysos with his consort Ariadne.

Mathura lion capital

The Mathura lion capital, which associates many of the Indo-Scythian rulers from Maues to Rajuvula, mentions a dedication of a relic of the Buddha in a stupa. It also bears centrally the Buddhist symbol of the triratana, and is also filled with mentions of the bhagavat Buddha Sakyamuni, and characteristically Buddhist phrases such as:

- "sarvabudhana puya dhamasa puya saghasa puya"

- "Revere all the Buddhas, revere the dharma, revere the sangha"

- (Mathura lion capital, inscription O1/O2)

Indo-Corinthian capital from Butkara Stupa, dated to 20 BCE, during the reign of Azes II. Turin City Museum of Ancient Art. |

Dancing Indo-Scythians (top) and hunting scene (bottom). Buddhist relief from Swat, Gandhara. |

Butkara door jamb, with Indo-Scythians dancing and reveling. On the back side is a relief of a standing Buddha[28] |

Indo-Scythians in Western sources

The presence of Scythian territory in northwestern India, and especially around the mouth of the Indus is mentioned extensively in Western maps and travel descriptions of the period. The Ptolemy world map, as well as the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea mention prominently Scythia in the Indus area, as well as Roman Tabula Peutingeriana. The Periplus states that Minnagara was the capital of Scythia, and that Parthian king were fighting for it during the 1st century CE. It also distinguishes Scythia with Ariaca further east (centered in Gujarat and Malwa), over which ruled the Western Satrap king Nahapana.

Indo-Scythians in Indian literature

The Indo-Scythians were named "Shaka" in India, an extension on the name Saka used by the Persians to designate Scythians. From the time of the Mahabharata wars (4000–1500 BCE roughly) Shakas receive numerous mentions in texts like the Puranas, the Manusmriti, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Mahabhasiya of Patanjali, the Brhat Samhita of Vraha Mihira, the Kavyamimamsa, the Brihat-Katha-Manjari, the Katha-Saritsagara and several other old texts. They are described as part of an amalgam of other war-like tribes from the northwest.

Sai-Wang Scythian hordes of Chipin or Kipin

A section of the Central Asian Scythians (under Sai-Wang) is said to have taken southerly direction and after passing through the Pamirs it entered the Chipin or Kipin after crossing the Hasuna-tu (Hanging Pass) located above the valley of Kanda in Swat country.[29] Chipin has been identified by Pelliot, Bagchi, Raychaudhury and some others with Kashmir[30] while other scholars identify it with Kapisha (Kafirstan).[31][32] The Sai-Wang had established his kingdom in Kipin. S. Konow interprets the Sai-Wang as Saka Murunda of Indian literature, Murunda being equal to Wang i.e. king, master or lord,[33] but Bagchi who takes the word Wang in the sense of the king of the Scythians but he distinguishes the Sai Sakas from the Murunda Sakas.[34] There are reasons to believe that Sai Scythians were Kamboja Scythians and therefore Sai-Wang belonged to the Scythianised Kambojas (i.e. Parama-Kambojas) of the Transoxiana region and came back to settle among his own stock after being evicted from his ancestral land located in Scythia or Shakadvipa. King Moga or Maues could have belonged to this group of Scythians who had migrated from the Sai country (Central Asia) to Chipin.[35] The Mathura Lion Capital inscriptions attest that the members of the family of King Moga (q.v.) had last name Kamuia or Kamuio (q.v.) which Khroshthi term has been identified by scholars with Sanskrit Kamboja or Kambojaka. Thus, Sai-Wang and his migrant hordes which came to settle in Kabol valley in Kapisha may indeed have been from the transoxian Parama Kambojas living in Shakadvipa or Scythian land.[36]

It is worth noting that many scholars think the Kambojas to be a Royal Clan of the Sakas or Scythians.[37][38][39][40][41]. This also seems to be confirmed from Mathura Lion Capital Inscriptions of Mahaksatrapa Rajuvula and the Rock Edicts V and XIII of King Aśoka [39].

Establishment of Mlechcha Kingdoms in Northern India

The mixed Scythian hordes that migrated to Drangiana and surrounding regions, later spread further into north and south-west India via the lower Indus valley. Their migration spread into Sovira, Gujarat, Rajasthan and northern India, including kingdoms in the Indian mainland.

There are important references to the warring Mleccha hordes of the Shakas, Yavanas, Kambojas and Pahlavas in the Bala Kanda of the Valmiki Ramayana also.[42]

Leading Indologists like H. C. Raychadhury glimpses in these verses the struggles between the Hindus and the invading hordes of Mlechcha barbarians from the northwest. The time frame for these struggles is the 2nd century BCE onwards. Raychadhury fixes the date of the present version of the Valmiki Ramayana around or after the 2nd century CE.[43]

This picture presented by the Ramayana probably refers to the political scenario that emerged when the mixed hordes descended from Sakasthan and advanced into the lower Indus valley via Bolan Pass and beyond into the Indian mainland. It refers to the hordes' struggle to seize political control of Sovira, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Punjab, Malwa, Maharashtra and further areas of eastern, central and southern India.

Mahabharata too furnishes a veiled hint about the invasion of the mixed hordes from the northwest. Vanaparava by Mahabharata contains verses in the form of prophecy deploring that "......the Mlechha (barbaric) kings of the Shakas, Yavanas, Kambojas, Bahlikas, etc. shall rule the earth (i.e. India) un-righteously in Kaliyuga..".[44]

According to H. C. Ray Chaudhury, this is too clear a statement to be ignored or explained away.

Mahabharata's epic reference apparently alludes to the chaotic politics which followed the collapse of the Mauryan and Sunga dynasties in northern India and the area's subsequent occupation by foreign hordes of the Saka, Yavana, Kamboja, Pahlavas, Bahlika, Shudra and Rishika tribes from the northwest.

See also: Migration of Kambojas

Evidence about joint invasions

The Scythian groups that invaded India and set up various kingdoms, included besides the Sakas other allied tribes, such as the Medii, Xanthii, Massagetae. These peoples were all absorbed into the community of Kshatriyas of mainstream Indian society.[45]

The Shakas were formerly a people of trans-Hemodos region---the Shakadvipa of the Puranas or the Scythia of the classical writings. Isidor of Charax (beginning of first c AD) attests them in Sakastana (modern Seistan). First century CE Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (c AD 70–80) also attests a Scythian district in lower Indus with Minnagra as its capital. Ptolemy (c AD 140) also attests Indo-Scythia in south-western India which comprised Patalene, Abhira and the Surastrene (Saurashtra) territories.

The 2nd century BCE Scythian invasion of India, was in all probability carried out jointly by the Sakas, Pahlavas, Kambojas, Paradas, Rishikas and other allied tribes from the northwest.[46] As a result, groups of these people who had originally lived in the northwest before the Christian era, were also found to have lived in southwest India in post-Christian times. All these groups of north-western peoples apparently entered Indian mainland following the Scythian invasion of India.

Main Indo-Scythian rulers

Northwestern India

- Maues, c 90–60 BCE

- Vonones, c 75–65 BCE

- Spalahores, c 75–65 BCE, satrap and brother of King Vonones, and probably the later King Spalirises.

- Spalirises, c 60–57 BCE, king and brother of King Vonones.

- Spalagadames c 50 BCE, satrap, and son of Spalahores.

- Azilises, before 60 BCE

- Azes I, c 60–20 BCE

- Zeionises, c 10 BCE – 10 CE

- Kharahostes, c 10 BCE – 10 CE

- Indravarman

- Hajatria

Kshaharatas

- Liaka Kusuluka, satrap of Chuksa

- Kusulaka Patika, satrap of Chuksa and son of Liaka Kusulaka

- Abhiraka

- Bhumaka

- Nahapana (founder of the Western Satraps)

Apracarajas (Bajaur area)

- Vijayamitra (12 BCE – 15 CE)

- Itravasu (c 20 CE)

- Aspavarma (15–45 CE)

Paratarajas

Obv: Robed bust of Bhimajhunasa left, wearing tiara-shaped diadem.

Rev: Swastika with legend around.

1.70g. Senior (Indo-Scythian) 286.1

- Kuvhusuvhume

- Spajhana

- Spajhayam

- Bhimajhuna

- Yolamira, son of Bagavera (2nd century)

- Arjuna, son of Yolamira (2nd century)

- Karyyanapa

- Hvaramira, another son of Yolamira(2nd century)

- Mirahvara, son of Hvaramira (2nd century)

- Miratakhma, another son of Hvaramira (2nd century)

"Northern Satraps" (Mathura area)

- Hagamasha (satrap, 1st century BCE)

- Hagana (satrap, 1st century BCE)

- Rajuvula, c 10 CE (Great Satrap)

- Sodasa, son of Rajuvula

- "Great Satrap" Kharapallana (c 130 CE)

- "Satrap" Vanaspara (c 130 CE)

Minor local rulers

- Bhadayasa

- Mamvadi

- Arsakes

Western Satraps

- Nahapana (119–124)

- Chastana (c 120), son of Ghsamotika

- Jayadaman, son of Chastana

- Rudradaman I (c 130–150), son of Jayadaman

- Damajadasri I (170–175)

- Jivadaman (175 d 199)

- Rudrasimha I (175–188 d 197)

- Isvaradatta (188–191)

- Rudrasimha I (restored) (191–197)

- Jivadaman (restored) (197–199)

- Rudrasena I (200–222)

- Samghadaman (222–223)

- Damasena (223–232)

- Damajadasri II (232–239) with

- Viradaman (234–238)

- Yasodaman I (239)

- Vijayasena (239–250)

- Damajadasri III (251–255)

- Rudrasena II (255–277)

- Visvasimha (277–282)

- Bhratadarman (282–295)

with

- Visvasena (293–304)

- Rudrasimha II, son of Lord (Svami) Jivadaman (304–348) with

- Yasodaman II (317–332)

- Rudradaman II (332–348)

- Rudrasena III (348–380)

- Simhasena (380– ?)

- Rudrasena IV (382–388)

- Rudrasimha III (388–395)

"Degraded Kshatriyas" from the northwest

The Manusmriti, written about 200, groups the Shakas with the Yavanas, Kambojas, Paradas, Pahlavas, Kiratas and the Daradas, etc., and addresses them all as "degraded warriors" or Kshatriyas" (X/43-44). Anushasanaparva of the Mahabharata also views the Shakas, Kambojas, Yavanas etc... in the same light. Patanjali in his Mahabhashya regards the Shakas and Yavanas as pure Shudras (II.4.10). The Vartika of the Katyayana informs us that the kings of the Shakas and the Yavanas, like those of the Kambojas, may also be addressed by their respective tribal names. The Mahabharata also associates the Shakas with the Yavanas, Gandharas, Kambojas, Pahlavas, Tusharas, Sabaras, Barbaras, etc. and addresses them all as the Barbaric tribes of Uttarapatha. In another verse, the same epic groups the Shakas and Kambojas and Khashas and addresses them as the tribes from Udichya i.e. north division (5/169/20). Also, the Kishkindha Kanda of the Ramayana locates the Shakas, Kambojas, Yavanas and Paradas in the extreme north-west beyond the Himavat (i.e. Hindukush) (43/12).

Military actions

Military alliance with Chandragupta (c 320 BC)

The Buddhist drama Mudrarakshas by Visakhadutta and the Jaina works Parisishtaparvan refer to Chandragupta's alliance with Himalayan king Parvataka.

This Himalayan alliance gave Chandragupta a powerful composite army made up of the frontier martial tribes of the Shakas, Kambojas, Yavanas, Parasikas, Bahlikas etc. which he utilised to defeat the Nanda rulers of Magadha, and thus establishing his Mauryan Empire in northern India (See: Mudrarakshas, II).

Invasion of India (c 180 BC)

The Vanaparva of the Mahabharata contains verses in the form of prophecy that the kings of the Shakas, Yavanas, Kambojas, Bahlikas and Abhiras etc. shall rule unrighteously in Kaliyuga (MBH 3/188/34-36).

This reference apparently alludes to the precarious political scenario following the collapse of Mauryan and Sunga dynasties in northern India and its occupation by foreign hordes of the Shakas, Yavanas, Kambojas and Pahlavas.

Extinction

The Brihat-Katha-Manjari of the Kshemendra (10/1/285-86) relates that around 400 AD, the Gupta king Vikramaditya (Chandragupta II) had "unburdened the sacred earth of the barbarians" like the Shakas, Mlecchas, Kambojas, Yavanas, Tusharas, Parasikas, Hunas, etc., by annihilating these "sinners" completely.

The 10th century Kavyamimamsa of Raj Shekhar (Ch. 17) still lists the Sakas, Tusharas, Vokanas, Hunas, Kambojas, Bahlikas, Pahlavas, Tangana, Turukshas, etc. together, and states them as the tribes located in the Uttarapatha division.

Descendants of the Indo-Scythians

There is speculation that a number of communities in South Asia, mainly in the northwestern regions, are partly descended from the Indo-Scythians. These include:

| Middle kingdoms of India | ||||||||||||

| Timeline: | Northwestern India | Northern India | Southern India | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

6th century BCE |

(Persian rule)

(Islamic conquests)

(Islamic Empire) |

|

|

|||||||||

See also

- Ahir

- Jats

- Ancient India and Central Asia

- Tillia tepe

Footnotes

- ↑ Ma-Twan-Lin's Chinese Encyclopedia of the 13th century CE states: "In ancient times, the Hiung-nu having defeated the Yue-chi, the latter went to the west and dwelt among the Ta-hia and the king of Sai went to southwards to live in Kipin. The tribes of Sai divided and dispersed so as to form here and there different kingdoms." Shin-chi, Chapter 123; Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 691; History and Culture of Indian People, The Age of Imperial Unity, p 122.

- ↑ Ch'ien Han-Shu's History of the first Han Dynasty says: "Formerly when the Hiung-nu conquered the Ta Yue-chi (Great Yue-chi), the latter migrated to the west and subjugated the Ta-hia whereupon the Sai-Wang went to South and ruled over Kipin" (Ch'ien Han-shu, Chapter 96A). The territory of the Wu-sun was originally the country of the Sai (Ch'ien Han-shu, Chapter 96B). The name of the Saiwang ruler is not given. Some scholars identify the Daxia (Ta-hia) in these records as Bactria (Cambridge History of India, Vol I, p 511, E. J. Rapson (Ed)).

- ↑ The Age of Imperial Unity, History and Culture of Indian People, p. 122, (Ed.) R. C. Majumdar, A. D. Pusalkar.

- ↑ The joint resistance of the Saka, Kamboja Parama-Kamboja), Rishika, Loha, Parada and Bahlikas tribes to the Yuezhi and migration south-west together reflected the strong ties between the neighbouring tribes since remote antiquity. Early Indian literature records military alliances between the Sakas, Kambojas, Pahlavas and Paradas. The ancient Puranic traditions mentions several joint invasions of India by the Scythians. The conflict between the Bahu-Sagara of India and the Haihaya-Kamboja-Saka-Pahlava-Yavana-Parada is well known as the war fought by "five hordes" (pāňca-ganha). The Sakas, Yavanas, Tusharas and Kambojas also fought the Kurukshetra war under the command of Sudakshina Kamboja. The Valmiki Ramayana also attests that the Sakas, Kambojas, Pahlavas and Yavanas fought together against the Vedic, Hindu king Vishwamitra of Kanauj.

- ↑ Justin XL.II.2

- ↑ Isodor of Charax, Sathmoi Parthikoi, 18.

- ↑ Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 693.

- ↑ The Sakas in India, p. 14, S. Chattopadhyaya; The Development of Khroshthi Script, p 77, C. C. Dasgupta; Hellenism in Ancient India, p 120, G. N. Banerjee; Ancient Kamboja, People and the Country, 1981, p 308

- ↑ Hindu Polity, 1943, p 144, K. P. Jayswal

- ↑ Parthian stations

- ↑ Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, 38

- ↑ "The dynastic art of the Kushans", John Rosenfield, p 130

- ↑ Kshatrapasa pra Kharaostasa Artasa putrasa. See: Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 398, H. C. Raychaudhury, B. N. Mukerjee; Ancient India, 1956, pp 220–221, R. K. Mukerjee

- ↑ Ancient India, pp 220–221, R. k. Mukerjee; Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol II, Part 1, p 36, D S Konow

- ↑ Jayaswal writes:"Mathura was under outlandish people like the Yavanas and Kambojas... who had a special mode of fighting" (Manu and Yajnavalkya, K. P. Jayswal); See also: Indian Historical Quarterly, XXVI-2, p 124. Shashi Asthana comments: "Epic Mahabharata refers to the siege of Mathura by the Yavanas and Kambojas (see: History and Archaeology of India's Contacts with Other Countries, from Earliest Times to 300 B.C., 1976, p 153, Shashi Asthana). cf: Ancient India, 1956, p 220, R. K. Mukerjee

- ↑ Mahabharata 12.101.5.

- ↑ Source: "A Catalogue of the Indian Coins in the British Museum. Andhras etc..." Rapson, p ciii

- ↑ A gap in Puranic history

- ↑ Francine Tissot "Gandhara", p74

- ↑ "Parthians, from about the 1st century AD, seem to have preferred to show off their carefully tonsured hair, usually only wearing a fillet of thick ribbon; before then, the Scythian cap or bashlyk was worn more frequently". In "Parthians and Sassanid Parthians" Peter Willcox ISBN 0-85045-688-6, p12

- ↑ Photographic reference here.

- ↑ "Let us remind that in Sirkap, stone palettes were found at all excavated levels. On the contrary, neither Bhir-Mound, the Maurya city preceding Sirkap on the Taxila site, nor Sirsukh, the Kushan city succeeding her, did deliver any stone palettes during their excavations", in "Les palettes du Gandhara", p89. "The terminal point after which such palettes are not manufactured anymore is probably located during the Kushan period. In effect, neither Mathura nor Taxila (although the Sirsukh had only been little excavated), nor Begram, nor Surkh Kotal, neither the great Kushan archaeological sites of Soviet Central Asia or Afghanistan have yielded such objects. Only four palettes have been found in Kushan-period archaeological sites. They come from secondary sites, such as Garav Kala and Ajvadz in Soviet Tajikistan and Jhukar, in the Indus Valley, and Dalverzin Tepe. They are rather roughly made." In "Les Palettes du Gandhara", Henri-Paul Francfort, p 91. (in French in the original)

- ↑ Source:"Butkara I", Faccena

- ↑ "Gandhara" Francine Tissot

- ↑ The Turin City Museum of Ancient Art Text and photographic reference: Terre Lontane > O2

- ↑ For the pilaster showing a man in Greek dress File:ButkaraPilaster.jpg.

- ↑ Facenna, "Sculptures from the sacred area of Butkara I", plate CCCLXXI. The relief is this one, showing Indo-Scythians dancing and reveling, with on the back side a relief of a standing Buddha (not shown).

- ↑ Faccenna, "Sculptures from the sacred area of Butkara I", plate CCCLXXII

- ↑ Serindia, Vol I, 1980 Edition, p 8, M. A. Stein

- ↑ Op cit p 693, H. C. Raychaudhury, B. N. Mukerjee; Early History of North India, p 3, S. Chattopadhyava; India and Central Asia, p 126, P. C. Bagchi

- ↑ Epigraphia Indiaca XIV, p 291 S Konow; Greeks in Bactria and India, p 473, fn, W. W. Tarn; Yuan Chwang I, pp 259–60, Watters; Comprehensive History of India, Vol I, p 189, N. K. Sastri; History and Culture of Indian People, The Age of Imperial Unity, 122; History and Culture of Indian People, Classical Age, p 617, R. C. Majumdar, A. D. Pusalkar.

- ↑ Scholars like E. J. Rapson, L. Petech etc. also connect Kipin with Kapisha. Levi holds that prior to 600 AD, Kipin denoted Kashmir, but after this it implied Kapisha See Discussion in The Classical Age, p 671.

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, II. 1. XX f; cf: Early History of North India, pp 54, S Chattopadhyaya.

- ↑ India and Central Asia, 1955, p 124, P. C. Bagchi; Geographical Data in Early Puranas, 1972, p 47, M. R. Singh.

- ↑ See: Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p fn 13, B. N. Mukerjee; Chilas, Islamabad, 1983, no 72, 78, 85, pp 98, 102, A. H. Dani

- ↑ This was the habitat of the Parama Kambojas referred to in Mahabharata (MBH 2.27.25) and were located in Transoxiana territory in Shakadvipa. It is not mere coincidence that modern Kamboj of Punjab have prominent clan names like Soi, Asoi and Sahi/Shahi: (see list of Kamboj Gotras). Similarly, Asoi clan of Kamboj can also be very well related to or connected with Asii or Asio of Strabo (See: Strabo XI.8,2.) which clan name undoubtedly represents people connected with horse-culture, which the ancient Kambojas pre-eminently were. The above evidence thus again points to a connection of the Sai/Sai-wang mentioned in Chinese chronicles and the Asii/Asio clan mentioned in Strabo's accounts with the Scythian Kambojas i.e. Parama Kambojas.

- ↑ Ref: La vieille route de l'Inde de Bactres à Taxila, p 271, Alfred A. Foucher.

- ↑ See also entry: Kamboja in online "Heritage du Sanskrit Dictionnaire, Sanskrit-Francais", 2008, p 101, Gerard Huet, which defines Kamboja as: Clan royal Kamboja des Śakās:(i.e Kambojas, a royal clan of the Sakas/Scythians). See link: [1]

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 See ref: A bilingual Graeco-Aramaic edict by Aśoka: the first Greek inscription discovered in Afghanistan , 1964, p 17, Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli, Giovanni Garbini - Aśoka, India, Published by Istituto italiano per il medio ed estremo Oriente, 1964

- ↑ See further references: Watching Cambodia: Ten Paths to Enter the Cambodian Tangle, 1993, p 51, Serge Thion - History. See also: Tai World: A Digest of Articles from the Thai -Yunnan Project Newsletter, Andrew Walker, Nicholas Tapp - Folklore - 2001 or Thai-Yunnan Project Newsletter (NEWSLETTER is edited by Scott Bamber and published in the Department of Anthropology, Research School of Pacific Studies; printed at Central Printery; the masthead is by Susan Wigham of Graphic Design (all of The Australian National University); Cf: History of Indian Administration, p 94, B. N. Puri.

- ↑ Indian Epic Mahabharata (See: Mahabharata 5.19.21-23; Dr F. E. Pargiter, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland) attests that Kamboja ruler Sudakshin Kamboj had marshaled and lead an Akshuni army of wrathful warriors which besides the Kambojas, also comprised a strong contingent from the Sakas (or Scythians). This fact clearly proves that the Sakas, in general, were subservient to the Kamboja ruler Sudakshina Kamboj and that Sudakshina's clan was ruling over the Sakas. Thus from epic evidence also, the Kambojas were indeed a royal or ruling Scythian clan and the Scythians had formed an indispensable part of the Kamboja army. Furthermore, the Mathura Lion Capital Inscriptions also connect yuvaraja Kharaosta Kamuia (Kamboja) and his daughter Aiyasi Kamuia (Kamboja), chief queen of the Scythian Mahakshatrapa Rajuvula, to the imperial house ruling in Taxila (See: Kharoshṭhī Inscriptions, Edition 1991, p 36, Sten Konow)

- ↑

- taih asit samvrita bhuumih Shakaih-Yavana mishritaih || 1.54-21 ||

- taih taih Yavana-Kamboja barbarah ca akulii kritaah || 1-54-23 ||

- tasya humkaarato jatah Kamboja ravi sannibhah |

- udhasah tu atha sanjatah Pahlavah shastra panayah || 1-55-2 ||

- yoni deshaat ca Yavanah Shakri deshat Shakah tathaa |

- roma kupesu Mlecchah ca Haritah sa Kiratakah || 1-55-3 ||.

- ↑ Political History of Ancient India, 1996, pp 3–4.

- ↑

- viparite tada loke purvarupa.n kshayasya tat || 34 ||

- bahavo mechchha rajanah prithivyam manujadhipa |

- mithyanushasinah papa mrishavadaparayanah || 35 ||

- Andhrah Shakah Pulindashcha Yavanashcha naradhipah |

- Kamboja Bahlikah Shudrastathabhira narottama || 36 ||

- — (MBH 3.188.34-36).

- ↑ History and Culture of Indian People, The Vedic Age, pp 286–87, 313–14.

- ↑ cf: Interaction Between India and Western World, pp 75–93, H. G. Rawlinson

- ↑ Bhim Singh Dahiya, Jats the Ancient Rulers, Dahinam Publishers, Sonepat, Haryana.

- ↑ B. S. Dhillon (1994). History and study of the Jats. Beta Publishers. ISBN 1895603021.

- ↑ J. Pettigrew, Robber Noblemen: A Study of the Political System of the Sikh Jats, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., London, 1975, pp 25, 238.

- ↑ P. S. Gill, Heritage of Sikh Culture, New Academic Publishing Co., Jullundur, Punjab, 1975, pp 12–13.

- ↑ Sara, I., The Scythian Origins of the Sikh-Jat, The Sikh Review, March 1978, pp 26–35.

- ↑ Mahil, U.S., Antiquity of Jat Race, Atma Ram & Sons, Delhi, India, 1955, pp 2, 9, 14.

References

- Bailey, H. W. 1958. "Languages of the Saka." Handbuch der Orientalistik, I. Abt., 4. Bd., I. Absch., Leiden-Köln. 1958.

- Faccenna D., "Sculptures from the sacred area of Butkara I", Istituto Poligrafico Dello Stato, Libreria Dello Stato, Rome, 1964.

- Harmatta, János, ed., 1994. History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Paris, UNESCO Publishing.

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu. Draft annotated English translation.[2]

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation. [3]

- Hulsewé, A. F. P. and Loewe, M. A. N. 1979. China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. E. J. Brill, Leiden.

- Litvinsky, B. A., ed., 1996. History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III. The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Paris, UNESCO Publishing.

- Liu, Xinru 2001 "Migration and Settlement of the Yuezhi-Kushan: Interaction and Interdependence of Nomadic and Sedentary Societies." Journal of World History, Volume 12, No. 2, Fall 2001. University of Hawaii Press, pp 261–292. [4].

- Bulletin of the Asia Institute: The Archaeology and Art of Central Asia. Studies From the Former Soviet Union. New Series. Edited by B. A. Litvinskii and Carol Altman Bromberg. Translation directed by Mary Fleming Zirin. Vol. 8, (1994), pp 37–46.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. 1970. "The Wu-sun and Sakas and the Yüeh-chih Migration." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 33 (1970), pp 154–160.

- Puri, B. N. 1994. "The Sakas and Indo-Parthians." In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Harmatta, János, ed., 1994. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, pp 191–207.

- Watson, Burton. Trans. 1961. Records of the Grand Historian of China: Translated from the Shih chi of Ssu-ma Ch'ien. Chapter 123: The Account of Ta-yüan, p 265. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08167-7

- Yu, Taishan. 1998. A Study of Saka History. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 80. July, 1998. Dept. of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Pennsylvania.

- Yu, Taishan. 2000. A Hypothesis about the Source of the Sai Tribes. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 106. September, 2000. Dept. of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Pennsylvania.

- Political History of Ancient India, 1996, H. C. Raychaudhury

- Hindu Polity, A Constitutional history of India in Hindu Times, 1978, K. P. Jayswal

- Geographical Data in Early Puranas, 1972, M. R. Singh

- India and Central Asia, 1955, P. C. Bagchi

- Geography of Puranas, 1973, S. M. Ali

- Greeks in Bactria and India, W. W. Tarn

- Early History of North India, S. Chattopadhyava

- Sakas in Ancient India, S. Chattopadhyava

- Development of Kharoshthi script, C. C. Dasgupta

- Ancient India, 1956, R. K. Mukerjee

- Ancient India, Vol III, T. L. Shah

- Hellenism in Ancient India, G. N. Banerjee

- Manu and Yajnavalkya, K. P. Jayswal

- Anabaseeos Alexanddrou, Arrian

- Geography, by Ptolemy

- Mathura Lion Capital Inscriptions

- Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarum, Vol II, Part I, S. Konow

External links

- "Indo-Scythian dynasties", RC Senior

- Coins of the Indo-Scythians

- Burner relief

- History of Greco-India

|

||||||||||||||