Poverty

Poverty is the lack of basic human needs, such as clean water, nutrition, health care, education, clothing and shelter, because of the inability to afford them.[1][2] This is also referred to as absolute poverty or destitution. Relative poverty is the condition of having fewer resources or less income than others within a society or country, or compared to worldwide averages. About 1.7 billion people live in absolute poverty; before the industrial revolution, poverty had mostly been the norm.[3][4]

Poverty reduction has historically been a result of economic growth as increased levels of production, such as modern industrial technology, made more wealth available for those who were otherwise too poor to afford them.[4][5] Also, investments in modernizing agriculture and increasing yields is considered the core of the antipoverty effort, given three-quarters of the world's poor are rural farmers.[6][7]

Today, continued economic development is constrained by the lack of economic freedoms. Economic liberalization includes extending property rights, especially to land, to the poor, and making financial services, notably savings, accessible.[8][9][10] Inefficient institutions, corruption and political instability can also discourage investment. Aid and government support in health, education and infrastructure helps growth by increasing human and physical capital.[4]

Contents |

Causes

Scarcity of basic needs

Before the industrial revolution, poverty had been mostly accepted as inevitable as economies produced little, making wealth scarce.[3] In Antwerp and Lyon, two of the largest cities in western Europe, by 1600 three-quarters of the total population were too poor to pay taxes.[11] In 18th century England, half the population was at least occasionally dependent on charity for subsistence.[12] In modern times, food shortages have been reduced dramatically in the developed world, thanks to agricultural technologies such as nitrogen fertilizers, pesticides and new irrigation methods.[13][14] Also, mass production of goods in places such as China has made what were once considered luxuries, such as vehicles or computers, inexpensive and thus accessible to many who were otherwise too poor to afford them.[15][16]

Rises in the costs of living make poor people less able to afford items. Poor people spend a greater portion of their budgets on food than richer people. As a result poor households, and those near the poverty threshold can be particularly vulnerable to increases in food prices. For example in late 2007 increases in the price of grains[17] led to food riots in some countries[18][19][20]. The World Bank warned that 100 million people were at risk of sinking deeper into poverty.[21] Threats to the supply of food may also be caused by drought and the water crisis.[22][23][24] Intensive farming often leads to a vicious cycle of exhaustion of soil fertility and decline of agricultural yields.[25] Approximately 40% of the world's agricultural land is seriously degraded.[26][27] In Africa, if current trends of soil degradation continue, the continent might be able to feed just 25% of its population by 2025, according to UNU's Ghana-based Institute for Natural Resources in Africa.[28]

Health care can be widely unavailable to the poor. The loss of health care workers emigrating from impoverished countries has a damaging effect. For example, an estimated 100,000 Philippine nurses emigrated between 1994 and 2006.[29] There are more Ethiopian doctors in Chicago than in Ethiopia.[30]

Overpopulation and lack of access to birth control methods drive poverty[31][32][33] The world's population is expected to reach nearly 9 billion in 2040.[34] However, the reverse is also true, that poverty causes overpopulation as it gives women little power to plan childhood, have educational attainment, or a career.[35]

Barriers to opportunities

The unwillingness of governments and feudal elites to give full-fledged property rights of land to their tenants is cited as the chief obstacle to development.[36] This lack of economic freedom inhibits entrepreneurship among the poor.[5] New enterprises and foreign investment can be driven away by the results of inefficient institutions, notably corruption, weak rule of law and excessive bureaucratic burdens.[4][5] Lack of financial services, as a result of restrictive regulations, such as the requirements for banking licenses, makes it hard for even smaller microsavings programs to reach the poor.[37]

It takes two days, two bureaucratic procedures, and $280 to open a business in Canada while an entrepreneur in Bolivia must pay $2,696 in fees, wait 82 business days, and go through 20 procedures to do the same.[5] Such costly barriers favor big firms at the expense of small enterprises, where most jobs are created.[5] In India before economic reforms, businesses had to bribe government officials even for routine activities, which was a tax on business in effect.[4]

Corruption, for example, in Nigeria, led to an estimated $400 billion of the country's oil revenue to be stolen by Nigeria's leaders between 1960 and 1999.[38][39] Lack of opportunities can further be caused by the failure of governments to provide essential infrastructure.[40][41].

Opportunities in richer countries drives talent away, leading to brain drains. This is mainly caused by richer countries' restrictions on Freedom of Movement of the poor, uneducated class. Entry visas are granted with much higher probability to the rich and educated of developing countries. Brain drain has cost the African continent over $4 billion in the employment of 150,000 expatriate professionals annually.[42] Indian students going abroad for their higher studies costs India a foreign exchange outflow of $10 billion annually.[43]

Poor health and education severely affects productivity. Inadequate nutrition in childhood undermines the ability of individuals to develop their full capabilities. Lack of essential minerals such as iodine and iron can impair brain development. 2 billion people (one-third of the total global population) are affected by iodine deficiency. In developing countries, it is estimated that 40% of children aged 4 and younger suffer from anemia because of insufficient iron in their diets. See also Health and intelligence.[44]

Similarly substance abuse, including for example alcoholism and drug abuse can consign people to vicious poverty cycles. Infectious diseases such as Malaria and tuberculosis can perpetuate poverty by diverting health and economic resources from investment and productivity; malaria decreases GDP growth by up to 1.3% in some developing nations and AIDS decreases African growth by 0.3-1.5% annually.[45][46][47]

War, political instability and crime, including violent gangs and drug cartels, also discourage investment. Civil wars and conflicts in Africa cost the continent some $300 billion between 1990 and 2005.[48] Eritrea and Ethiopia spent hundreds of millions of dollars on the war that resulted in minor border changes.[49] Shocks in the business cycle affect poverty rates, increasing in recessions and declining in booms. Cultural factors, such as discrimination of various kinds, can negatively affect productivity such as age discrimination, stereotyping,[50] gender discrimination, racial discrimination, and caste discrimination.[51]

Max Weber and the modernization theory suggest that cultural values could affect economic success.[52][53] However, researchers have gathered evidence that suggest that values are not as deeply ingrained and that changing economic opportunities explain most of the movement into and out of poverty, as opposed to shifts in values.[54]

Effects of poverty

The effects of poverty may also be causes, as listed above, thus creating a "poverty cycle" operating across multiple levels, individual, local, national and global.

Health

Hunger, disease, and less education describe a person in poverty. One third of deaths - some 18 million people a year or 50,000 per day - are due to poverty-related causes: in total 270 million people, most of them women and children, have died as a result of poverty since 1990.[55] Those living in poverty suffer disproportionately from hunger or even starvation and disease.[56] Those living in poverty suffer lower life expectancy. According to the World Health Organization, hunger and malnutrition are the single gravest threats to the world's public health and malnutrition is by far the biggest contributor to child mortality, present in half of all cases.[57]

Every year nearly 11 million children living in poverty die before their fifth birthday. 1.02 billion people go to bed hungry every night.[58] Poverty increases the risk of homelessness.[59] There are over 100 million street children worldwide.[60] Increased risk of drug abuse may also be associated with poverty.[61]

According to the Global Hunger Index, South Asia has the highest child malnutrition rate of the world's regions.[62] Nearly half of all Indian children are undernourished,[63] one of the highest rates in the world and nearly double the rate of Sub-Saharan Africa.[64] Every year, more than half a million women die in pregnancy or childbirth.[65] Almost 90% of maternal deaths occur in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, compared to less than 1% in the developed world.[66]

Women who have children born in poverty cannot nourish the children efficiently with the right prenatal care. They may also suffer from disease that may be passed down to the child through birth. Asthma is a common problem children acquire when born into poverty.

Education

Research has found that there is a high risk of educational underachievement for children who are from low-income housing circumstances. This often is a process that begins in primary school for some less fortunate children. In the US educational system, these children are at a higher risk than other children for retention in their grade, special placements during the school’s hours and even not completing their high school education.[67] There are indeed many explanations for why students tend to drop out of school. For children with low resources, the risk factors are similar to excuses such as juvenile delinquency rates, higher levels of teenage pregnancy, and the economic dependency upon their low income parent or parents.[67]

Families and society who submit low levels of investment in the education and development of less fortunate children end up with less favorable results for the children who see a life of parental employment reduction and low wages. Higher rates of early childbearing with all the connected risks to family, health and well-being are majorly important issues to address since education from preschool to high school are both identifiably meaningful in a life.[67]

Poverty often drastically affects children’s success in school. A child’s “home activities, preferences, mannerisms” must align with the world and in the cases that they do not these students are at a disadvantage in the school and most importantly the classroom.[68] Therefore, it is safe to state that children who live at or below the poverty level will have far less success educationally than children who live above the poverty line. Poor children have a great deal less healthcare and this ultimately results in many absences from the academic year. Additionally, poor children are much more likely to suffer from hunger, fatigue, irritability, headaches, ear infections, flu, and colds.[68] These illnesses could potentially restrict a child or student’s focus and concentration.

Housing

Slum-dwellers, who make up a third of the world's urban population, live in a poverty no better, if not worse, than rural people, who are the traditional focus of the poverty in the developing world, according to a report by the United Nations.[69]

Most of the children living in institutions around the world have a surviving parent or close relative, and they most commonly entered orphanages because of poverty.[70] Experts and child advocates maintain that orphanages are expensive and often harm children’s development by separating them from their families.[70] It is speculated that, flush with money, orphanages are increasing and push for children to join even though demographic data show that even the poorest extended families usually take in children whose parents have died.[70]

Violence

According to a UN report on modern slavery, the most common form of human trafficking is for prostitution, which is largely fueled by poverty.[71][72] In Zimbabwe, a number of girls are turning to prostitution for food to survive because of the increasing poverty.[73] In one survey, 67% of children from disadvantaged inner cities said they had witnessed a serious assault, and 33% reported witnessing a homicide.[74] 51% of fifth graders from New Orleans (median income for a household: $27,133) have been found to be victims of violence, compared to 32% in Washington, DC (mean income for a household: $40,127).[75]

Drug abuse

Unemployment and distance from rural areas are where most drug abuse occurs. Drug abuse can result in a community shouldering the impact of many nefarious acts such as stealing, killing, theft, sexual assault, and prostitution. Drug abuse is synonymous with poor performance in school & work, and a general malaise of intra-personal intelligence. People who have abused drugs and have spent all of their money buying substances—i.e. heroin, alcohol, methamphetamines etc.—become addicts. This induces a downward spiral in the functionality of most addicts, as the drugs and poverty can be cyclical. When an addict has no other way to support their addiction they result to illegal measures to obtain income. This is where a community becomes affected by drug abuse. The urge—or “Jonesin”—for many different substances begins to take over an addict’s life.

Poverty reduction

Historically, poverty reduction has been largely a result of economic growth.[4][5] The industrial revolution led to high economic growth and eliminated mass poverty in what is now considered the developed world.[3][5] In 1820, 75% of humanity lived on less than a dollar a day, while in 2001, only about 20% do.[5] As three quarters of the world's poor live in the country side, the World Bank cites helping small farmers as the heart of the fight against poverty.[7] Economic growth in agriculture is, on average, at least twice as effective in benefiting the poorest half of a country’s population as growth generated in non-agricultural sectors.[76] However, aid is essential in providing better lives for those who are already poor and in sponsoring medical and scientific efforts such as the green revolution and the eradication of smallpox.[36][77]

Economic liberalization

Ian Vásquez, director of the Cato Institute's Project on Global Economic Liberty, wrote that extending property rights protection to the poor is one of the most important poverty reduction strategies a nation could take.[5] Securing property rights to land, the largest asset for most societies, is vital to their economic freedom.[5][36] The World Bank concludes increasing land rights is ‘the key to reducing poverty’ citing that land rights greatly increase poor people’s wealth, in some cases doubling it.[10] Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto has estimated that state recognition of the property of the poor would give them assets worth 40 times all the foreign aid since 1945.[5] Although approaches varied, the World Bank said the key issues were security of tenure and ensuring land transactions were low cost.[10]

In China and India, noted reductions in poverty in recent decades have occurred mostly as a result of the abandonment of collective farming in China and the cutting of government red tape in India.[78] However, ending government sponsorship of social programs is sometimes advocated as a free market principle with tragic consequences. For example, the World Bank presses poor nations to eliminate subsidies for fertilizer even while many farmers cannot afford them at market prices.[79] The reconfiguration of public financing in former Soviet states during their transition to a market economy called for reduced spending on health and education, sharply increasing poverty.[80][81][82]

Trade liberalization increases the total surplus of trading nations. Remittances sent to poor countries, such as India, are sometimes larger than foreign direct investment and total remittances are more than double aid flows from OECD countries.[83] Foreign investment and export industries helped fuel the economic expansion of fast growing Asian nations.[84] However, trade rules are often unfair as they block access to richer nations’ markets and ban poorer nations from supporting their industries.[79][85] Processed products from poorer nations, in contrast to raw materials, get vastly higher tariffs at richer nations' ports.[86] A University of Toronto study found the dropping of duty charges on thousands of products from African nations because of the African Growth and Opportunity Act was directly responsible for a "surprisingly large" increase in imports from Africa.[87] However, Chinese textile and clothing exports have encountered criticism from Europe, the United States and some African countries.[88][89]

Deals can also be negotiated to favor developing countries such as China, where laws compel foreign multinationals to train their future Chinese competitors in strategic industries and render themselves redundant in the long term.[90] In Thailand, the 51 percent rule compels multinational corporations starting operations in Thailand give 51 percent control to a Thai company in a joint venture.[91]

Capital, infrastructure and technology

Investments in human capital, in the form of health, is needed for economic growth. Nations do not necessarily need wealth to gain health.[92] For example, Sri Lanka had a maternal mortality rate of 2% in the 1930s, higher than any nation today.[93] It reduced it to .5-.6% in the 1950s and to .06% today while spending less each year on maternal health because it learned what worked and what did not.[93] Cheap water filters and promoting hand washing are some of the most cost effective health interventions and can cut deaths from diarrhea and pneumonia.[94][95] Knowledge on the cost effectiveness of healthcare interventions can be elusive but educational measures to disseminate what works are available, such as the disease control priorities project.[92]

Human capital, in the form of education, is an even more important determinant of economic growth than physical capital.[4] Deworming children costs about 50 cents per child per year and reduces non-attendance from anemia, illness and malnutrition and is only a twenty-fifth as expensive to increase school attendance as by constructing schools.[96]

UN economists argue that good infrastructure, such as roads and information networks, helps market reforms to work.[97] China claims it is investing in railways, roads, ports and rural telephones in African countries as part of its formula for economic development.[97] It was the technology of the steam engine that originally began the dramatic decreases in poverty levels. Cell phone technology brings the market to poor or rural sections.[98] With necessary information, remote farmers can produce specific crops to sell to the buyers that brings the best price.[99]

Such technology also makes financial services accessible to the poor. Those in poverty place overwhelming importance on having a safe place to save money, much more so than receiving loans.[8] Also, a large part of microfinance loans are spent on products that would usually be paid by a checking or savings account.[8] Mobile banking addresses the problem of the heavy regulation and costly maintenance of saving accounts.[8] Mobile financial services in the developing world, ahead of the developed world in this respect, could be worth $5 billion by 2012.[100] Safaricom’s M-Pesa launched one of the first systems where a network of agents of mostly shopkeepers, instead of bank branches, would take deposits in cash and translate these onto a virtual account on customers' phones. Cash transfers can be done between phones and issued back in cash with a small commission, making remittances safer.[9]

Aid

Aid in its simplest form is a basic income grant, a form of social security periodically providing citizens with money. In pilot projects in Namibia, where such a program pays just $13 a month, people were able to pay tuition fees, raising the proportion of children going to school by 92%, child malnutrition rates fell from 42% to 10% and economic activity grew by 10%.[101][102] Researchers say it is more efficient to support the families and extended families that care for the vast majority of orphans with simple allocations of cash than supporting orphanages, who get most of the aid.[70]

Some aid, such as Conditional Cash Transfers, can be rewarded based on desirable actions such as enrolling children in school or receiving vaccinations.[103] In Mexico, for example, dropout rates of 16-19 year olds in rural area dropped by 20% and children gained half an inch in height.[104] Initial fears that the program would encourage families to stay at home rather than work to collect benefits have proven to be unfounded. Instead, there is less excuse for neglectful behavior as, for example, children stopped begging on the streets instead of going to school because it could result in suspension from the program.[104]

Another form of aid is microloans, made famous by the Grameen Bank, where small amounts of money are loaned to farmers or villages, mostly women, who can then obtain physical capital to increase their economic rewards. For example, the Thai government's People's Bank, makes loans of $100 to $300 to help farmers buy equipment or seeds, help street vendors acquire an inventory to sell, or help others set up small shops. While advancing the woman and her household's position economically, microloans empower women and enable them to voice their opinions in general household decisions.[105]

Aid from non-governmental organizations may be more effective than governmental aid; this may be because it is better at reaching the poor and better controlled at the grassroots level.[106] Critics argue that some of the foreign aid is stolen by corrupt governments and officials, and that higher aid levels erode the quality of governance. Policy becomes much more oriented toward what will get more aid money than it does towards meeting the needs of the people.[107] Supporters of aid argue that these problems may be solved with better auditing of how the aid is used.[107] Immunization campaigns for children, such as against polio, diphtheria and measles have save millions of lives.[77]

A major proportion of aid from donor nations is tied, mandating that a receiving nation spend on products and expertise originating only from the donor country.[108] For example, Eritrea is forced to spend aid money on foreign goods and services to build a network of railways even though it is cheaper to use local expertise and resources.[108] US law requires food aid be spent on buying food at home, instead of where the hungry live, and, as a result, half of what is spent is used on transport.[109]

One of the proposed ways to help poor countries has been debt relief. Many less developed nations have gotten themselves into extensive debt to banks and governments from the rich nations and interest payments on these debts are often more than a country can generate per year in profits from exports.[110] If poor countries do not have to spend so much on debt payments, they can use the money instead for priorities which help reduce poverty such as basic health-care and education.[111] For example, Zambia began offering services, such as free health care even while overwhelming the health care infrastructure, because of savings that resulted from the rounds of debt relief in 2005.[112]

Good institutions

Efficient institutions that are not corrupt and obey the rule of law make and enforce good laws that provide security to property and businesses. Efficient and fair governments would work to invest in the long-term interests of the nation rather than plunder resources through corruption.[4] Researchers at UC Berkeley developed what they called a "Weberianness scale" which measures aspects of bureaucracies and governments Max Weber described as most important for rational-legal and efficient government over 100 years ago. Comparative research has found that the scale is correlated with higher rates of economic development.[113]

With their related concept of good governance World Bank researchers have found much the same: Data from 150 nations have shown several measures of good governance (such as accountability, effectiveness, rule of law, low corruption) to be related to higher rates of economic development. [114] The United Nations Development Program published a report in April 2000 which focused on good governance in poor countries as a key to economic development and overcoming the selfish interests of wealthy elites often behind state actions in developing nations. The report concludes that “Without good governance, reliance on trickle-down economic development and a host of other strategies will not work.” [115]

Examples of good governance leading to economic development and poverty reduction include Thailand, Taiwan, Malaysia, South Korea, and Vietnam, which tend to have a strong government, called a hard state or development state. These “hard states” have the will and authority to create and maintain policies that lead to long-term development that helps all their citizens, not just the wealthy. Multinational corporations are regulated so that they follow reasonable standards for pay and labor conditions, pay reasonable taxes to help develop the country, and keep some of the profits in the country, reinvesting them to provide further development. In 1957 South Korea had a lower per capita GDP than Ghana,[116] and by 2008 it was 17 times as high as Ghana's.[117]

Funds from aid and natural resources are often diverted into private hands and then sent to banks overseas as a result of graft.[57] If Western banks rejected stolen money, says a report by Global Witness, ordinary people would benefit “in a way that aid flows will never achieve”.[57] The report asked for more regulation of banks as they have proved capable of stanching the flow of funds linked to terrorism, money-laundering or tax evasion.[57]

Empowering women

Empowering women has helped some countries increase and sustain economic development.[118] When given more rights and opportunities women begin to receive more education, thus increasing the overall human capital of the country; when given more influence women seem to act more responsibly in helping people in the family or village; and when better educated and more in control of their lives, women are more successful in bringing down rapid population growth because they have more say in family planning.[119]

Demographics

Percentage of population living on less than $1.25 per day. UN estimates 2000-2006.

Percentage of population suffering from hunger, World Food Programme, 2006

The Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality.

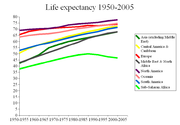

Life expectancy has been increasing and converging for most of the world. Sub-Saharan Africa has recently seen a decline, partly related to the AIDS epidemic. Graph shows the years 1950-2005.

|

Absolute poverty

Poverty is usually measured as either absolute or relative poverty (the latter being actually an index of income inequality). Absolute poverty refers to a set standard which is consistent over time and between countries. The World Bank defines extreme poverty as living on less than US $1.25 (PPP) per day, and moderate poverty as less than $2 a day. It estimates that "in 2001, 1.1 billion people had consumption levels below $1 a day and 2.7 billion lived on less than $2 a day."[120]

Six million children die of hunger every year - 17,000 every day.[121] Selective Primary Health Care has been shown to be one of the most efficient ways in which absolute poverty can be eradicated in comparison to Primary Health Care which has a target of treating diseases. Disease prevention is the focus of Selective Primary Health Care which puts this system on higher grounds in terms of preventing malnutrition and illness, thus putting an end to Absolute Poverty.[122]

The proportion of the developing world's population living in extreme economic poverty fell from 28 percent in 1990 to 21 percent in 2001.[120] Most of this improvement has occurred in East and South Asia.[123] In East Asia the World Bank reported that "The poverty headcount rate at the $2-a-day level is estimated to have fallen to about 27 percent [in 2007], down from 29.5 percent in 2006 and 69 percent in 1990."[124] In Sub-Saharan Africa extreme poverty went up from 41 percent in 1981 to 46 percent in 2001, which combined with growing population increased the number of people living in extreme poverty from 231 million to 318 million.[125]

In the early 1990s some of the transition economies of Eastern Europe and Central Asia experienced a sharp drop in income.[126] The collapse of the Soviet Union resulted in large declines in GDP per capita, of about 30 to 35% between 1990 and the trough year of 1998 (when it was at its minimum). As a result poverty rates also increased although in subsequent years as per capita incomes recovered the poverty rate dropped from 31.4% of the population to 19.6%[127][128] The World Bank issued a report predicting that between 2007 and 2027 the populations of Georgia and Ukraine will decrease by 17% and 24% respectively.[129]

World Bank data shows that the percentage of the population living in households with consumption or income per person below the poverty line has decreased in each region of the world since 1990:[130][131]

| Region | 1990 | 2002 | 2004 |

|---|---|---|---|

| East Asia and Pacific | 15.40% | 12.33% | 9.07% |

| Europe and Central Asia | 3.60% | 1.28% | 0.95% |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 9.62% | 9.08% | 8.64% |

| Middle East and North Africa | 2.08% | 1.69% | 1.47% |

| South Asia | 35.04% | 33.44% | 30.84% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 46.07% | 42.63% | 41.09% |

Other human development indicators have also been improving. Life expectancy has greatly increased in the developing world since WWII and is starting to close the gap to the developed world. Child mortality has decreased in every developing region of the world. The proportion of the world's population living in countries where per-capita food supplies are less than 2,200 calories (9,200 kilojoules) per day decreased from 56% in the mid-1960s to below 10% by the 1990s. Similar trends can be observed for literacy, access to clean water and electricity and basic consumer items.[132]

There are various criticisms of these measurements.[133] Shaohua Chen and Martin Ravallion note that although "a clear trend decline in the percentage of people who are absolutely poor is evident ... with uneven progress across regions...the developing world outside China and India has seen little or no sustained progress in reducing the number of poor".

Since the world's population is increasing, a constant number living in poverty would be associated with a diminishing proportion. Looking at the percentage living on less than $1/day, and if excluding China and India, then this percentage has decreased from 31.35% to 20.70% between 1981 and 2004.[134]

The 2007 World Bank report "Global Economic Prospects" predicts that in 2030 the number living on less than the equivalent of $1 a day will fall by half, to about 550 million. An average resident of what we used to call the Third World will live about as well as do residents of the Czech or Slovak republics today. Much of Africa will have difficulty keeping pace with the rest of the developing world and even if conditions there improve in absolute terms, the report warns, Africa in 2030 will be home to a larger proportion of the world's poorest people than it is today.[135]

The reason for the faster economic growth in East Asia and South Asia is a result of their relative backwardness, in a phenomenon called the convergence hypothesis or the conditional convergence hypothesis. Because these economies began modernizing later than richer nations, they could benefit from simply adapting technological advances which enable higher levels of productivity that had been invented over centuries in richer nations.

Relative poverty

Relative poverty views poverty as socially defined and dependent on social context, hence relative poverty is a measure of income inequality. Usually, relative poverty is measured as the percentage of population with income less than some fixed proportion of median income. There are several other different income inequality metrics, for example the Gini coefficient or the Theil Index.

Relative poverty measures are used as official poverty rates in several developed countries. As such these poverty statistics measure inequality rather than material deprivation or hardship. The measurements are usually based on a person's yearly income and frequently take no account of total wealth. The main poverty line used in the OECD and the European Union is based on "economic distance", a level of income set at 60% of the median household income.[136]

Other aspects

Economic aspects of poverty focus on material needs, typically including the necessities of daily living, such as food, clothing, shelter, or safe drinking water. Poverty in this sense may be understood as a condition in which a person or community is lacking in the basic needs for a minimum standard of well-being and life, particularly as a result of a persistent lack of income.

Analysis of social aspects of poverty links conditions of scarcity to aspects of the distribution of resources and power in a society and recognizes that poverty may be a function of the diminished "capability" of people to live the kinds of lives they value.[138] The social aspects of poverty may include lack of access to information, education, health care, or political power.[139][140]

Poverty may also be understood as an aspect of unequal social status and inequitable social relationships, experienced as social exclusion, dependency, and diminished capacity to participate, or to develop meaningful connections with other people in society.[141][142][143] Such social exclusion can be minimized through strengthened connections with the mainstream, such as through the provision of relational care to those who are experiencing poverty.

The World Bank's "Voices of the Poor," based on research with over 20,000 poor people in 23 countries, identifies a range of factors which poor people identify as part of poverty.[145] These include:

- Precarious livelihoods

- Excluded locations

- Physical limitations

- Gender relationships

- Problems in social relationships

- Lack of security

- Abuse by those in power

- Dis-empowering institutions

- Limited capabilities

- Weak community organizations

David Moore, in his book The World Bank, argues that some analysis of poverty reflect pejorative, sometimes racial, stereotypes of impoverished people as powerless victims and passive recipients of aid programs.[146]

Ultra-poverty, a term apparently coined by Michael Lipton,[147] connotes being amongst poorest of the poor in low-income countries. Lipton defined ultra-poverty as receiving less than 80 percent of minimum caloric intake whilst spending more than 80% of income on food. Alternatively a 2007 report issued by International Food Policy Research Institute defined ultra-poverty as living on less than 54 cents per day.[148] BRAC (NGO) has pioneered a program called Targeting the Ultra-Poor to redress ultra-poverty by working with individual ultra-poor women.[149]

Voluntary poverty

| "'Tis the gift to be simple, 'tis the gift to be free, 'tis the gift to come down where you ought to be, And when we find ourselves in the place just right, It will be in the valley of love and delight." |

| —Shaker song.[150] |

Among some individuals, such as ascetics, poverty is considered a necessary or desirable condition, which must be embraced in order to reach certain spiritual, moral, or intellectual states. Poverty is often understood to be an essential element of renunciation in religions such as Buddhism (only for monks, not for lay persons) and Jainism, whilst in Roman Catholicism it is one of the evangelical counsels.

Certain religious orders also take a vow of extreme poverty. For example, the Franciscan orders have traditionally foregone all individual and corporate forms of ownership. While individual ownership of goods and wealth is forbidden for Benedictines, following the Rule of St. Benedict, the monastery itself may possess both goods and money, and throughout history some monasteries have become very rich.

In this context of religious vows, poverty may be understood as a means of self-denial in order to place oneself at the service of others; Pope Honorius III wrote in 1217 that the Dominicans "lived a life of voluntary poverty, exposing themselves to innumerable dangers and sufferings, for the salvation of others". Following Jesus' warning that riches can be like thorns that choke up the good seed of the word (Matthew 13:22), voluntary poverty is often understood by Christians as of benefit to the individual – a form of self-discipline by which one distances oneself from distractions from God.

See also

|

|

|

|

Nations:

- Poverty by country

- Least Developed Countries

- Countries by fertility rate

- Countries by GDP (PPP)

- Countries by poverty rate

Theology:

- Relational care

- Sadaqah

- Zakat

Organizations and campaigns

|

|

In documentary photography and film

|

|

References

- ↑ http://encarta.msn.com/encnet/features/dictionary/DictionaryResults.aspx?lextype=3&search=poverty Encarta Poverty definition

- ↑ Sociology in our times

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Under traditional (i.e., nonindustrialized) modes of economic production, widespread poverty had been accepted as inevitable. The total output of goods and services, even if equally distributed, would still have been insufficient to give the entire population a comfortable standard of living by prevailing standards. With the economic productivity that resulted from industrialization, however, this ceased to be the case" Encyclopedia Britannica, "Poverty"

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Krugman, Paul, and Robin Wells. Macroeconomics. 2. New York City: Worth Publishers, 2009. Print.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 Ending Mass Poverty by Ian Vásquez

- ↑ Obama enlists major powers to aid poor farmers with $15 billion

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 World Bank report puts agriculture at core of antipoverty effort

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 http://www.time.com/time/business/article/0,8599,1918733,00.html Microfinance’s next step: deposits

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/8194241.stm Africa’s mobile banking revolution

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Land rights help fight poverty

- ↑ "Europe in crisis, 1598-1648". Geoffrey Parker (2001). p.11. ISBN 0-631-22028-3

- ↑ "Why did the American Revolution take place?". Digital History.

- ↑ http://www.theatlantic.com/issues/97jan/borlaug/borlaug.htm Forgotten benefactor of humanity

- ↑ BBC Ethical Man

- ↑ In Laos, Chinese motorcycles change lives

- ↑ China boosts African economies, offering a second opportunity

- ↑ The cost of food: Facts and figures

- ↑ Riots and hunger feared as demand for grain sends food costs soaring

- ↑ Already we have riots, hoarding, panic: the sign of things to come?

- ↑ Feed the world? We are fighting a losing battle, UN admits

- ↑ 100 million at risk from rising food costs

- ↑ Global Water Shortages May Cause Food Shortages

- ↑ Vanishing Himalayan Glaciers Threaten a Billion

- ↑ Big melt threatens millions, says UN

- ↑ Exploitation and Over-exploitation in Societies Past and Present, Brigitta Benzing, Bernd Herrmann

- ↑ The Earth Is Shrinking: Advancing Deserts and Rising Seas Squeezing Civilization

- ↑ Global food crisis looms as climate change and population growth strip fertile land

- ↑ Africa may be able to feed only 25% of its population by 2025

- ↑ Philippine Medical Brain Drain Leaves Public Health System in Crisis - VoA News, retrieved 29 May 2008

- ↑ "Out of Africa - health workers leave in droves". Telegraph. November 2, 2004.

- ↑ "Population growth driving climate change, poverty: experts". Agence France-Presse. September 21, 2009.

- ↑ "Birth rates 'must be curbed to win war on global poverty". The Independent. January 31, 2007.

- ↑ "Another Inconvenient Truth: The World's Growing Population Poses a Malthusian Dilemma". Scientific American. October 2, 2009.

- ↑ "World Population Clock — Worldometers".

- ↑ http://www.henrygeorge.org/popsup.htm

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 How to spread democracy

- ↑ Savings revolution

- ↑ "Anti-Corruption Climate Change: it started in Nigeria". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

- ↑ "Nigeria: The Hidden Cost of Corruption". Public Broadcasting Service (PBS).

- ↑ Global Competitiveness Report 2006, World Economic Forum, Website

- ↑ Infrastructure and Poverty Reduction: Cross-country Evidence Hossein Jalilian and John Weiss. 2004.

- ↑ Brain drain in Africa

- ↑ Students’ exodus costs India forex outflow of $10 bn: Assocham, Thaindian News, January 26, 2009

- ↑ Hunger and Malnutrition paper by Jere R Behrman, Harold Alderman and John Hoddinott.

- ↑ Economic costs of AIDS

- ↑ The economic and social burden of malaria

- ↑ Poverty Issues Dominate WHO Regional Meeting

- ↑ "Wars cost Africa $18 billion US a year: report". CBC News. October 11, 2007.

- ↑ "Will arms ban slow war?". BBC News. May 18, 2000.

- ↑ Ending Poverty in Community (EPIC)

- ↑ UN report slams India for caste discrimination

- ↑ Moore, Wilbert. 1974. Social Change. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hill.

- ↑ Parsons, Talcott. 1966. Societies: Evolutionary and Comparative Perspectives. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- ↑ Kerbo, Harold. 2006. Social Stratification and Inequality: Class Conflict in Historical, Comparative, and Global Perspective, 6th edition New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ The World Health Report, World Health Organization (See annex table 2)

- ↑ Rising food prices curb aid to global poor

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 Malnutrition The Starvelings

- ↑ 1.02 billion people hungry. FAO, 2009.

- ↑ Study: 744,000 homeless in United States

- ↑ Street Children

- ↑ Health warning over Russian youth

- ↑ "2008 Global Hunger Index Key Findings & Facts". 2008. http://www.ifpri.org/media/200610GHI/GHIFindings.asp.

- ↑ "Half of India's children malnourished, says NGO report". Calcutta News. October 15, 2009.

- ↑ "India: Undernourished Children: A Call for Reform and Action". World Bank. http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/SOUTHASIAEXT/0,,contentMDK:20916955~pagePK:146736~piPK:146830~theSitePK:223547,00.html.

- ↑ "Maternal mortality ratio falling too slowly to meet goal". WHO. October 12, 2007.

- ↑ "The causes of maternal death". BBC News. November 23, 1998.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 Huston, A. C. (1991). Children in Poverty: Child Development and Public Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Solley, Bobbie A. (2005). When Poverty’s Children Write: Celebrating Strengths, Transforming Lives. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, Inc.

- ↑ Report reveals global slum crisis

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 70.3 Aid gives alternatives to African orphanages

- ↑ Experts encourage action against sex trafficking

- ↑ Child sex boom fueled by poverty

- ↑ Zimbabwean girls trade sex for food

- ↑ Atkins, M. S., McKay, M., Talbott, E., & Arvantis, P. (1996). "DSM-IV diagnosis of conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder: Implications and guidelines for school mental health teams," School Psychology Review, 25, 274-283. Citing: Bell, C. C., & Jenkins, E. J. (1991). "Traumatic stress and children," Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 2, 175-185.

- ↑ Atkins, M. S., McKay, M., Talbott, E., & Arvantis, P. (1996). "DSM-IV diagnosis of conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder: Implications and guidelines for school mental health teams," School Psychology Review, 25, 274-283. Citing: Osofsky, J. D., Wewers, S., Harm, D. M., & Fick, A. C. (1993). "Chronic community violence: What is happening to our children?," Psychiatry, 56, 36-45; and, Richters, J. E., & Martinez, P (1993). "The NIMH community violence project: Vol. 1. Children as victims of and witnesses to violence," Psychiatry, 56, 7-21.

- ↑ Poverty- Climate change:Bangladesh facing the challenge

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Why aid does work

- ↑ Can aid bring an end to poverty

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Ending famine simply by ignoring the experts

- ↑ Transition: The First Ten Years – Analysis and Lessons for Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union, The World Bank, Washington, DC, 2002, p. 4.

- ↑ "Study Finds Poverty Deepening in Former Communist Countries". New York Times. October 12, 2000.

- ↑ Child poverty soars in eastern Europe". BBC News. October 11, 2000.

- ↑ Migration and development: The aid workers who really help

- ↑ Vogel, Ezra F. 1991. The Four Little Dragons: The Spread of Industrialization in East Asia. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Market access

- ↑ Make trade fair

- ↑ Relaxed trade rules boost African development

- ↑ "SOUTH AFRICA: Fallout as China sews up textile market". IRIN Africa. June 29, 2005.

- ↑ Growth of China's textile industry slows". Chinadaily.com.cn. March 21, 2007.

- ↑ http://www.spiegel.de/international/spiegel/0,1518,465007-3,00.html Does Communism work after all?

- ↑ Muscat, Robert J. 1994. The Fifth Tiger: A Study of Thai Development. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Disease Control Priorities Project

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Saving millions for just a few dollars

- ↑ India's Tata launches water filter for rural poor

- ↑ Millions mark UN hand washing day

- ↑ How can we help the world’s poor

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 China becomes Africa's suitor

- ↑ Give cash not food

- ↑ Market approach recasts often-hungry Ethiopia as potential bread basket

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/8100388.stm Africa pioneers mobile bank push

- ↑ http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/0,1518,642310,00.html A new approach to aid: How a basic income program saved a Namibian village

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7415814.stm Namibians line up for free cash

- ↑ Brazil becomes antipoverty showcase

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 Latin America makes dent in poverty with ‘conditional cash’ programs

- ↑ Grasmuck, Sherri and Espinal, Rosario. 2000. Market Success or Female Autonomy? Income,Ideology, and Empowerment among Microentrepreneurs in the Dominican Republic. Gender and Society 14 (2):231-255.

- ↑ Does Foreign Aid Reduce Poverty? Empirical Evidence from Nongovernmental and Bilateral Aid

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 MYTH: More Foreign Aid Will End Global Poverty

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 http://ipsnews.net/interna.asp?idnews=24509 Tied aid strangling nations, says UN

- ↑ Let them eat micronutrients

- ↑ World Bank and International Monetary Fund. 2001. Heavily Indebted Poor Countries, Progress Report. Retrieved from Worldbank.org.

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/4081220.stm African debt relief

- ↑ Zambia overwhelmed by free health care

- ↑ Evans, Peter, and James E. Rauch. 1999. "Bureaucracy and Growth: A Cross-National Analysis of the Effects of 'Weberian' State Structures on Economic Growth." American Sociological Review, 64:748-765.

- ↑ Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A; Zoido-Lobaton, P.. "Governance Matters.". World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 2196. Washington DC.

- ↑ United Nations Development Report. 2000. Overcoming Human Poverty: UNDP Poverty Report 2000. New York: United Nations Publications.

- ↑ Leading article: Africa has to spend carefully. The Independent. July 13, 2006.

- ↑ Data refer to the year 2008. $26,341 GDP for Korea, $1513 for Ghana. World Economic Outlook Database-October 2008, International Monetary Fund. Accessed on February 14, 2009.

- ↑ "Does Population Growth Impact Climate Change?. Scientific American. July 29, 2009.

- ↑ World Bank. 2001. Engendering Development--Through Gender Equality in Right, Resources and Voice. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 The World Bank, 2007, Understanding Poverty

- ↑ "U.N. chief: Hunger kills 17,000 kids daily - CNN.com". CNN. November 17, 2009. http://edition.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/europe/11/17/italy.food.summit/. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ↑ Walsh, Julia A., and Kenneth S. Warren. 1980. Selective primary health care: An interim strategy for disease control in developing countries. Social Science & Medicine. Part C: Medical Economics 14 (2):145-163.

- ↑ Shaohua Chen and Martin Ravallion, 2007, "How Have the World's Poorest Fared Since the Early 1980s?" Table 3, p. 28. [1]

- ↑ World Bank, 14 November 2007, 'East Asia Remains Robust Despite US Slow Down' [2]

- ↑ The Independent, 'Birth rates must be curbed to win war on global poverty', 31 January 2007 [3]

- ↑ Worldbank.org reference

- ↑ World Bank, Data and Statistics,WDI, GDF, & ADI Online Databases

- ↑ "Study Finds Poverty Deepening in Former Communist Countries". The New York Times. October 12, 2000.

- ↑ "East: 'If Countries Don't Act Now, It's Going To Be Too Late'". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 2007. http://www.rferl.org/featuresarticle/2007/6/0E4DF063-3807-420D-B551-B3D07F7AA84C.html. Retrieved 2007-12-22.

- ↑ World Bank, 2007, Povcalnet Poverty Data

- ↑ The data can be replicated using World Bank 2007 Human Development Indicator regional tables, and using the default poverty line of $32.74 per month at 1993 PPP.

- ↑ World Development Volume 33, Issue 1 , January 2005, Pages 1-19, Why Are We Worried About Income? Nearly Everything that Matters is Converging

- ↑ Institute of Social Analysis

- ↑ Shaohua Chen and Martin Ravallion, 2007, "How Have the World's Poorest Fared Since the Early 1980s?"[4]

- ↑ World Bank has Good News About Future, by Andrew Cassel, The Philadelphia Inquirer. December 30, 2006

- ↑ Michael Blastland (2009-07-31). "Just what is poor?". BBC NEWS. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/8177864.stm. Retrieved 2008-09-25.

- ↑ Slums, Stocks, Stars and the New India. Spiegel Online. February 28, 2007.

- ↑ Amartya Sen, 1985, Commodities and Capabilities, Amsterdam, New Holland, cited in Siddiqur Rahman Osmani, 2004, Evolving Views on Poverty: Concept, Assessment, and Strategy, ADB.org

- ↑ A Glossary for Social Epidemiology Nancy Krieger, PhD, Harvard School of Public Health

- ↑ Journal of Poverty

- ↑ H Silver, 1994, social exclusion and social solidarity, in International Labour Review, 133 5-6

- ↑ G Simmel, The poor, Social Problems 1965 13

- ↑ P Townsend, 1979, Poverty in the UK, Penguin

- ↑ "U.S. Government Does Relatively Little to Lessen Child Poverty Rates". Economic Policy Institute.

- ↑ Voices of the Poor

- ↑ Chapter on Voices of the Poor in David Moore's edited book The World Bank: Development, Poverty, Hegemony (University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2007)

- ↑ Lipton, Michael (1986), ’Seasonality and ultra-poverty’, Sussex, IDS Bulletin 17.3

- ↑ International Food Policy Research Institute, The World’s Most Deprived. Characteristics and Causes of Extreme Poverty and Hunger, Washington: IFPRI Oct 2007

- ↑ Matin, Imran, et al,, “Crafting a Graduation Pathway for the Ultra-poor: Lessons and Evidence from a BRAC Programme,” Research and Evaluation Division Working Paper, BRAC, 2008: Research Papers in Economics

- ↑ Simple Gifts

- ↑ Campaign to Reduce Poverty in America

- ↑ [5]

- ↑ The ONE Campaign

- ↑ United Nations Millennium Campaign

- ↑ Stand Against Poverty

Further reading

- Agricultural Research, Livelihoods, and Poverty: Studies of Economic and Social Impacts in Six Countries Edited by Michelle Adato and Ruth Meinzen-Dick (2007), Johns Hopkins University Press, International Food Policy Research Institute

- World Bank, Can South Asia End Poverty in a Generation?

- "Educate a Woman, You Educate a Nation" - South Africa Aims to Improve its Education for Girls WNN - Women News Network. Aug. 28, 2007. Lys Anzia

- Anthony Atkinson. Poverty in Europe 1998

- Betson, David M., and Jennifer L. Warlick "Alternative Historical Trends in Poverty." American Economic Review 88:348-51. 1998. in JSTOR

- Brady, David "Rethinking the Sociological Measurement of Poverty" Social Forces 81#3 2003, pp. 715–751 Online in Project Muse. Abstract: Reviews shortcomings of the official U.S. measure; examines several theoretical and methodological advances in poverty measurement. Argues that ideal measures of poverty should: (1) measure comparative historical variation effectively; (2) be relative rather than absolute; (3) conceptualize poverty as social exclusion; (4) assess the impact of taxes, transfers, and state benefits; and (5) integrate the depth of poverty and the inequality among the poor. Next, this article evaluates sociological studies published since 1990 for their consideration of these criteria. This article advocates for three alternative poverty indices: the interval measure, the ordinal measure, and the sum of ordinals measure. Finally, using the Luxembourg Income Study, it examines the empirical patterns with these three measures, across advanced capitalist democracies from 1967 to 1997. Estimates of these poverty indices are made available.

- Buhmann, Brigitte, Lee Rainwater, Guenther Schmaus, and Timothy M. Smeeding. 1988. "Equivalence Scales, Well-Being, Inequality, and Poverty: Sensitivity Estimates Across Ten Countries Using the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Database." Review of Income and Wealth 34:115-42.

- Cox, W. Michael, and Richard Alm. Myths of Rich and Poor 1999

- Danziger, Sheldon H., and Daniel H. Weinberg. "The Historical Record: Trends in Family Income, Inequality, and Poverty." Pp. 18–50 in Confronting Poverty: Prescriptions for Change, edited by Sheldon H. Danziger, Gary D. Sandefur, and Daniel. H. Weinberg. Russell Sage Foundation. 1994.

- Firebaugh, Glenn. "Empirics of World Income Inequality." American Journal of Sociology (2000) 104:1597-1630. in JSTOR

- Gans, Herbert, J., "The Uses of Poverty: The Poor Pay All", Social Policy, July/August 1971: pp. 20–24

- George, Abraham, Wharton Business School Publications - Why the Fight Against Poverty is Failing: A Contrarian View

- Gordon, David M. Theories of Poverty and Underemployment: Orthodox, Radical, and Dual Labor Market Perspectives. 1972.

- Haveman, Robert H. Poverty Policy and Poverty Research. University of Wisconsin Press 1987.

- John Iceland; Poverty in America: A Handbook University of California Press, 2003

- Alice O'Connor; "Poverty Research and Policy for the Post-Welfare Era" Annual Review of Sociology, 2000

- Osberg, Lars, and Kuan Xu. "International Comparisons of Poverty Intensity: Index Decomposition and Bootstrap Inference." The Journal of Human Resources 2000. 35:51-81.

- Paugam, Serge. "Poverty and Social Exclusion: A Sociological View." Pp. 41–62 in The Future of European Welfare, edited by Martin Rhodes and Yves Meny, 1998.

- Pressman, Steven, Poverty in America: An Annotated Bibliography. University Press of America and Scarecrow Press, 1994

- Rothman, David J., (editor). "The Almshouse Experience", in series Poverty U.S.A.: The Historical Record, 1971. ISBN 0-405-03092-4

- Amartya Sen; Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation Oxford University Press, 1982

- Amartya Sen. Development as Freedom (1999)

- Smeeding, Timothy M., Michael O'Higgins, and Lee Rainwater. Poverty, Inequality and Income Distribution in Comparative Perspective. Urban Institute Press 1990.

- Stephen C. Smith, Ending Global Poverty: A Guide to What Works, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005

- Triest, Robert K. "Has Poverty Gotten Worse?" Journal of Economic Perspectives 1998. 12:97-114.

- World Bank, "World Development Report 2004: Making Services Work For Poor People", 2004.

- Frank, Ellen, Dr. Dollar: How Is Poverty Defined in Government Statistics? Dollars & Sense, January/February 2006

- Bergmann, Barbara. "Deciding Who's Poor", Dollars & Sense, March/April 2000

- Babb, Sarah (2009). Behind the Development Banks: Washington Politics, World Poverty, and the Wealth of Nations. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226033655.

- Richard Wilson and Kate Pickett. "The Spirit Level", Allen Lane 2009

- Philippou, Lambros (2010) "Public Space, Enlarged Mentality and Being-In-Poverty", Philosophical Inquiry, Vol. XXX11, NO. 1-2 pp. 103–115.

External links

- Disease control priorities project Studies the cost effectiveness of health care interventions

- Human Rights Watch Tracks the abuse of people in less developed countries around the world.

- Luxembourg Income Study Contains a wealth of data on income inequality and poverty, and hundreds of its sponsored research papers using this data.

- Multinational Monitor Contains reports of corporate misbehavior around the world.

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development Contains reports on economic development as well as relations between rich and poor nations.

- Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI) Research to advance the human development approach to poverty reduction.

- Transparency International Tracks issues of government and corporate corruption around the world.

- United Nations Hundres of free reports related to economic development and standards of living in countries around the world, such as the annual Human Development Report.

- U.S. Agency for International Development USAID is the primary U.S. government agency with the mission for aid to developing countries.

- World Congress of Muslim Philanthropists Association that helps Islamic donors organize contributions.

- World Bank Contains hundreds of reports which can be downloaded for free, such as the annual World Development Report.

- World Food Program Associated with the United Nations, the World Food Program compiles hundreds of reports on hunger and food security around the world.

- Islamic Development Bank

- Islamic relief Largest Muslim relief organization.

- The Pulsera Project A US based non-profit Organization alleviating poverty in Nicaragua, Central America's second poorest nation.

- Is Life Getting Better : What is Poverty? Pamphlet describing the basic idea of poverty and how to measure it, from OECD's Measuring Progress project.

- PovertyVision.org ("the first daily poverty newspaper in the world")

|

||||||||||||||