Imran Khan

|

||||

| Personal information | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Imran Khan Niazi | |||

| Born | 25 November 1952 Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan |

|||

| Batting style | Right-handed | |||

| Bowling style | Right-arm fast | |||

| Role | All-rounder | |||

| International information | ||||

| National side | Pakistan | |||

| Test debut (cap 65) | 3 June 1971 v England | |||

| Last Test | 7 January 1992 v Sri Lanka | |||

| ODI debut (cap 12) | 31 August 1974 v England | |||

| Last ODI | 25 March 1992 v England | |||

| Domestic team information | ||||

| Years | Team | |||

| 1977 – 1988 | Sussex | |||

| 1984/85 | New South Wales | |||

| 1975 – 1981 | PIA | |||

| 1971 – 1976 | Worcestershire | |||

| 1973 – 1975 | Oxford University | |||

| 1969 – 1971 | Lahore | |||

| Career statistics | ||||

| Competition | Test | ODI | FC | LA |

| Matches | 88 | 175 | 382 | 425 |

| Runs scored | 3807 | 3709 | 17771 | 10100 |

| Batting average | 37.69 | 33.41 | 36.79 | 33.22 |

| 100s/50s | 6/18 | 1/19 | 30/93 | 5/66 |

| Top score | 136 | 102* | 170 | 114* |

| Balls bowled | 19458 | 7461 | 65224 | 19122 |

| Wickets | 362 | 182 | 1287 | 507 |

| Bowling average | 22.81 | 26.61 | 22.32 | 22.31 |

| 5 wickets in innings | 23 | 1 | 70 | 6 |

| 10 wickets in match | 6 | n/a | 13 | n/a |

| Best bowling | 8/58 | 6/14 | 8/34 | 6/14 |

| Catches/stumpings | 28/– | 36/– | 117/– | 84/– |

| Source: CricketArchive, 26 June 2008 | ||||

Imran Khan Niazi (Punjabi, Urdu: عمران خان نیازی) (born 25 November 1952) is a retired Pakistani cricketer who played international cricket for two decades in the late twentieth century and has been a politician since the mid-1990s. Currently, besides his political activism, Khan is also a charity worker and cricket commentator.

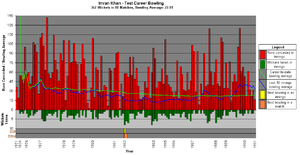

Khan played for the Pakistani cricket team from 1971 to 1992 and served as its captain intermittently throughout 1982-1992. After retiring from cricket at the end of the 1987 World Cup, he was called back to join the team in 1988. At 39, Khan led his teammates to Pakistan's first and only World Cup victory in 1992. He has a record of 3807 runs and 362 wickets in Test cricket, making him one of eight world cricketers to have achieved an 'All-rounder's Triple' in Test matches.[1] On 14 July 2010, Khan was inducted into the ICC Cricket Hall of Fame.[2]

In April 1996, Khan founded and became the chairman of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (Movement for Justice), a small and marginal political party, of which he is the only member ever elected to Parliament.[3] He represented Mianwali as a member of the National Assembly from November 2002 to October 2007.[4] Khan, through worldwide fundraising, helped establish the Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital & Research Centre in 1996 and Mianwali's Namal College in 2008.

Contents |

Family, education, and personal life

Imran Khan was born to Shaukat Khanum (Burki)[5] and Ikramullah Khan Niazi, a civil engineer, in Lahore. A quiet and shy boy in his youth, Khan grew up in a middle-class Niazi Pathan family with four sisters.[6] Settled in Punjab, Khan's father descended from the Pashtun (Pathan) Niazi Shermankhel tribe of Mianwali in Punjab .[7] Imran's Mother Shaukat Khanam (Burki's) family includes successful hockey players[5] and cricketers such as Javed Burki and Majid Khan.[7] Khan was educated at Aitchison College, the Cathedral School in Lahore, and the Royal Grammar School Worcester in England, where he excelled at cricket. In 1972, he enrolled to study Philosophy, Politics and Economics at Keble College, Oxford, where he graduated with a second-class degree in Politics and a third in Economics.[8]

On 16 May 1995, Khan married English socialite Jemima Goldsmith, a convert to Islam, in a two-minute Islamic ceremony in Paris. A month later, on 21 June, they were married again in a civil ceremony at the Richmond register office in England, followed by a reception at the Goldsmiths' house in Surrey.[9] The marriage, described as "tough" by Khan,[7] produced two sons, Sulaiman Isa (born 18 November 1996) and Kasim (born 10 April 1999).[10] As an agreement of his marriage, Khan spent four months a year in England. On 22 June 2004, it was announced that the Khans had divorced because it was "difficult for Jemima to adapt to life in Pakistan".[11]

Khan now resides in Bani Gala, Islamabad, where he built a farmhouse with the money he gained from selling his London flat. He grows fruit trees, wheat, and keeps cows, while also maintaining a cricket ground for his two sons, who visit during their holidays.[7]

Cricket career

Khan made a lacklustre first-class cricket debut at the age of sixteen in Lahore. By the start of the 1970s, he was playing for his home teams of Lahore A (1969–70), Lahore B (1969–70), Lahore Greens (1970–71) and, eventually, Lahore (1970–71).[12] Khan was part of Oxford University's Blues Cricket team during the 1973-75 seasons.[8] At Worcestershire, where he played county cricket from 1971 to 1976, he was regarded as only an average medium pace bowler. During this decade, other teams represented by Khan include Dawood Industries (1975–76) and Pakistan International Airlines (1975–76 to 1980-81). From 1983 to 1988, he played for Sussex.[1]

In 1971, Khan made his Test cricket debut against England at Birmingham. Three years later, he debuted in the One Day International (ODI) match, once again playing against England at Nottingham for the Prudential Trophy. After graduating from Oxford and finishing his tenure at Worcestershire, he returned to Pakistan in 1976 and secured a permanent place on his native national team starting from the 1976-77 season, during which they faced New Zealand and Australia.[12] Following the Australian series, he toured the West Indies, where he met Tony Greig, who signed him up for Kerry Packer's World Series Cricket.[1].His credentials as one of the fastest bowlers of the world started to establish when he finished third at 139.7 km/h in a fast bowling contest at Perth in 1978, behind Jeff Thomson and Michael Holding, but ahead of Dennis Lillee, Garth Le Roux and Andy Roberts.[1]. Khan also achieved a Test Cricket Bowling rating of 922 points against India on 30 January 1983. Highest at the time, the performance ranks third on ICC's All Time Test Bowling Rating.[13].

Khan achieved the all-rounder's triple (securing 3000 runs and 300 wickets) in 75 Tests, the second fastest record behind Ian Botham's 72. He is also established as having the second highest all-time batting average of 61.86 for a Test batsman playing at position 6 of the batting order.[14] He played his last Test match for Pakistan in January 1992, against Sri Lanka at Faisalabad. Khan retired permanently from cricket six months after his last ODI, the historic 1992 World Cup final against England at Melbourne, Australia.[15] He ended his career with 88 Test matches, 126 innings and scored 3807 runs at an average of 37.69, including six centuries and 18 fifties. His highest score was 136 runs. As a bowler, he took 362 wickets in Test cricket, which made him the first Pakistani and world's fourth bowler to do so.[1] In ODIs, he played 175 matches and scored 3709 runs at an average of 33.41. His highest score remains 102 not out. His best ODI bowling is documented at 6 wickets for 14 runs.

Captaincy

At the height of his career, in 1982, the thirty-year old Khan took over the captaincy of the Pakistani cricket team from Javed Miandad. Recalling his initial discomfort with this new role, he later said, "When I became the cricket captain, I couldn’t speak to the team directly I was so shy. I had to tell the manager, I said listen can you talk to them, this is what I want to convey to the team. I mean early team meetings I use to be so shy and embarrassed I couldn’t talk to the team."[16] As a captain, Khan played 48 Test matches, out of which 14 were won by Pakistan, 8 lost and the rest of 26 were drawn. He also played 139 ODIs, winning 77, losing 57 and ending one in a tie.[1]

In the team's second match under his leadership, Khan led them to their first Test win on English soil for 28 years at Lord's.[17] Khan's first year as captain was the peak of his legacy as a fast bowler as well as an all-rounder. He recorded the best Test bowling of his career while taking 8 wickets for 58 runs against Sri Lanka at Lahore in 1981-82.[1] He also topped both the bowling and batting averages against England in three Test series in 1982, taking 21 wickets and averaging 56 with the bat. Later the same year, he put up a highly acknowledged performance in a home series against the formidable Indian team by taking 40 wickets in six Tests at an average of 13.95. By the end of this series in 1982-83, Khan had taken 88 wickets in 13 Test matches over a period of one year as captain.[12]

This same Test series against India, however, also resulted in a stress fracture in his shin that kept him out of cricket for more than two years. An experimental treatment funded by the Pakistani government helped him recover by the end of 1984 and he made a successful comeback to international cricket in the latter part of the 1984-85 season.[1]

In 1987, Khan led Pakistan to its first Test series win in India, which was followed by Pakistan's first series victory in England the same year.[17] During the 1980s, his team also recorded three creditable draws against the West Indies. India and Pakistan co-hosted the 1987 World Cup, but neither ventured beyond the semi-finals. Khan retired from international cricket at the end of the World Cup. In 1988, he was asked to return to the captaincy by the President Of Pakistan, General Zia-Ul-Haq, and on 18 January, he announced his decision to rejoin the team.[1] Soon after returning to the captaincy, Khan led Pakistan to another winning tour in the West Indies, which he has recounted as "the last time I really bowled well".[7] He was declared Man of the Series against West Indies in 1988 when he took 23 wickets in 3 tests.[1]

Khan's career-high as a captain and cricketer came when he led Pakistan to victory in the 1992 Cricket World Cup. Playing with a brittle batting lineup, Khan promoted himself as a batsman to play in the top order along with Javed Miandad, but his contribution as a bowler was minimal. At the age of 39, Khan scored the highest runs of all the Pakistani batsmen and took the winning last wicket himself.[12] Khan's acceptance of the World Cup trophy on behalf of the Pakistani team, however, drew criticism. It was reported that Khan's decision to not mention his teammates and his country in his acceptance speech, and instead his focus on himself and his upcoming cancer hospital, "annoyed and embarrassed" many citizens. "Imran's 'I' 'Me' and 'My' speech has upset everyone," read an editorial in the Daily Nation newspaper, which labeled the acceptance speech a "jarring note".[18]

Post-retirement

In 1994, Khan had admitted that, during Test matches, he "occasionally scratched the side of the ball and lifted the seam." He had also added, "Only once did I use an object. When Sussex were playing Hampshire in 1981 the ball was not deviating at all. I got the 12th man to bring out a bottle top and it started to move around a lot."[19] In 1996, Khan successfully defended himself in a libel action brought forth by former English captain and all-rounder Ian Botham and batsman Allan Lamb over comments they alleged were made by Khan in two articles about the above-mentioned ball-tampering and another article published in an Indian magazine, India Today. They claimed that, in the latter publication, Khan had called the two cricketers "racist, ill-educated and lacking in class." Khan protested that he had been misquoted, saying that he was defending himself after having admitted that he tampered with a ball in a county match 18 years ago.[20] Khan won the libel case, which the judge labeled a "complete exercise in futility", with a 10-2 majority decision by the jury.[20]

Since retiring, Khan has written opinion pieces on cricket for various British and Asian newspapers, especially regarding the Pakistani national team. His contributions have been published in India's Outlook magazine,[21], the Guardian,[22] the Independent, and the Telegraph. Khan also sometimes appears as a cricket commentator on Asian and British sports networks, including BBC Urdu[23] and the Star TV network.[24] In 2004, when the Indian cricket team toured Pakistan after 14 years, he was a commentator on TEN Sports' special live show, Straight Drive,[25] while he was also a columnist for sify.com for the 2005 India-Pakistan Test series.[26] He has provided analysis for every cricket World Cup since 1992, which includes providing match summaries for BBC during the 1999 World Cup.[26]

In November 2009 Khan underwent emergency surgery at Lahore's Shaukat Khanum Cancer Hospital to remove an obstruction in his small intestine.[27]

Social work

For more than four years after retiring from cricket in 1992, Khan focused his efforts solely on social work. By 1991, he had founded the Shaukat Khanum Memorial Trust, a charity organization bearing the name of his mother, Mrs. Shaukat Khanum. As the Trust's maiden endeavor, Khan established Pakistan's first and only cancer hospital, constructed using donations and funds exceeding $25 million, raised by Khan from all over the world.[3] Inspired by the memory of his mother, who died of cancer, the Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital & Research Centre, a charitable cancer hospital with 75 percent free care, opened in Lahore on 29 December 1994.[7] Khan currently serves as the chairman of the hospital and continues to raise funds through charity and public donations.[28] Princess of Wales [Lady Diana] also visited Lahore in 1996 in order to raise funds for the Cancer hospital.

During the 1990s, Khan also served as UNICEF's Special Representative for Sports[29] and promoted health and immunization programmes in Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Thailand.[30]

On 27 April 2008, Khan's brainchild, a technical college in the Mianwali District called Namal College, was inaugurated. Namal College was built by the Mianwali Development Trust (MDT), as chaired by Khan, and was made an associate college of the University of Bradford in December 2005.[31] Currently, Khan is building another cancer hospital in Karachi, using his successful Lahore institution as a model. While in London, he also works with the Lord’s Taverners, a cricket charity.[3]

Political work

| Imran Khan Niazi | |

|

|

|

| Born | November 25, 1952 Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan |

|---|---|

| Political party | Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf |

| Spouse(s) | Jemima Khan (1995 - 2004) |

| Children | 2 |

| Residence | Lahore |

| Occupation | Political activist / social worker |

| Religion | Islam |

| Website | http://www.insaf.pk/ |

A few years after the end of his professional career as a cricketer, Khan entered electoral politics while admitting that he had never voted in an election before.[32] Since then, his most significant political work has been to protest against ruling politicians such as Pervez Musharraf and Asif Ali Zardari and his opposition to the US and UK foreign policy. Khan's "politics are not taken seriously in Pakistan and at best rated as single column news items in most newspapers."[33] As reported and by his own admission, Khan's most prominent political supporters are women and the youth.[6] His political foray was influenced by Lieutenant General Hamid Gul, the former Pakistani intelligence chief famous for fueling the Taliban's rise in Afghanistan and for his anti-West viewpoint.[34] In Pakistan, the reaction to his political work has been reported to be such that, "Mention his name at dinner tables and the reaction is the same: people roll their eyes, chuckle lightly, then exhale a sad sigh."[35]

On 25 April 1996, Khan founded his own political party called the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) with a proposed slogan of "Justice, Humanity and Self Esteem."[7] Khan, who contested from 7 districts, and members of his party were universally defeated at the polls in the 1997 general elections. Khan supported General Pervez Musharraf's military coup in 1999, but denounced his presidency a few months before the 2002 general elections. Many political commentators and his opponents termed Khan's change in opinion an opportunistic move. "I regret supporting the referendum. I was made to understand that when he won, the general would begin a clean-up of the corrupt in the system. But really it wasn't the case," he later explained.[36] During the 2002 election season, he also voiced his opposition to Pakistan's logistical support of US troops in Afghanistan by claiming that their country had become a "servant of America."[36] PTI won 0.8% of the popular vote and one out of 272 open seats on the 20 October 2002 legislative elections. Khan, who was elected from the NA-71 constituency of Mianwali, was sworn in as an MP on 16 November.[37] Once in office, Khan voted in favor of the pro-Taliban Islamist candidate for prime minister in 2002, bypassing Musharraf's choice.[34] As an MP, he was part of the Standing Committees on Kashmir and Public Accounts, and expressed legislative interest in Foreign Affairs, Education and Justice.[38]

On 6 May 2005, Khan became one of the first Muslim figures to criticize a 300-word Newsweek story about the alleged desecration of the Qur'an in a U.S. military prison at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba. Khan held a press conference to denounce the article and demanded that Gen. Pervez Musharraf secure an apology from American president George W. Bush for the incident.[34] In 2006, he exclaimed, "Musharraf is sitting here, and he licks George Bush’s shoes!" Criticizing Muslim leaders supportive of the Bush administration, he added, "They are the puppets sitting on the Muslim world. We want a sovereign Pakistan. We do not want a president to be a poodle of George Bush."[16] During George W. Bush's visit to Pakistan in March 2006, Khan was placed under house arrest in Islamabad after his threats of organizing a protest.[7] In June 2007, the federal Parliamentary Affairs Minister Dr. Sher Afghan Khan Niazi and the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) party filed separate ineligibility references against Khan, asking for his disqualification as member of the National Assembly on grounds of immorality. Both references, filed on the basis of articles 62 and 63 of the Constitution of Pakistan, were rejected on 5 September.[39]

On 2 October 2007, as part of the All Parties Democratic Movement, Khan joined 85 other MPs to resign from Parliament in protest of the Presidential election scheduled for 6 October, which General Musharraf was contesting without resigning as army chief.[4] On 3 November 2007, Khan was put under house arrest at his father's home hours after President Musharraf declared a state of emergency in Pakistan. Khan had demanded the death penalty for Musharraf after the imposition of emergency rule, which he equated to "committing treason". The next day, on 4 November, Khan escaped and went into peripatetic hiding.[40] He eventually came out of hiding on 14 November to join a student protest at the University of the Punjab.[41] At the rally, Khan was captured by students from the Jamaat-i-Islami political party, who claimed that Khan was an uninvited nuisance at the rally, and they handed him over to the police, who charged him under the Anti-terrorism act for allegedly inciting people to pick up arms, calling for civil disobedience, and for spreading hatred.[42] Incarcerated in the Dera Ghazi Khan Jail, Khan's relatives had access to him and were able to meet him to deliver goods during his week-long stay in jail. On 19 November, Khan let out the word through PTI members and his family that he had begun a hunger strike but the Deputy Superintendent of Dera Ghazi Khan Jail denied this news, saying that Khan had bread, eggs and fruit for breakfast.[43] Khan was one of the 3,000 political prisoners released from imprisonment on 21 November 2007.[44]

His party boycotted the national elections on 18 February 2008 and hence, no member of PTI has served in Parliament since Khan's resignation in 2007. Despite no longer being a member of Parliament, Khan was placed under house arrest in the crackdown by Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari of anti-government protests on 15 March 2009.

Ideology

Khan's proclaimed political platform and declarations include: Islamic values, to which he rededicated himself in the 1990s; liberal economics, with the promise of deregulating the economy and creating a welfare state; decreased bureaucracy and anti-corruption laws, to create and ensure a clean government; the establishment of an independent judiciary; overhaul of the country's police system; and an anti-militant vision for a democratic Pakistan.[15][24][45]

Khan has credited his decision to enter politics with a spiritual awakening, influenced by his conversations with a mystic from the Sufi sect of Islam that began in the last years of his cricket career. "I never drank or smoked, but I used to do my share of partying. In my spiritual evolution there was a block," he explained to the American Washington Post. As an MP, Khan sometimes voted with a bloc of hard-line religious parties such as the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal, whose leader, Maulana Fazlur Rehman, he supported for prime minister over Musharraf's candidate in 2002. Rehman is a pro-Taliban cleric who has called for holy war against the United States.[24] On religion in Pakistan, Khan has said that, "As time passes by, religious thought has to evolve, but it is not evolving, it is reacting against Western culture and often has nothing to do with faith or religion."

Khan told Britain's Daily Telegraph, "I want Pakistan to be a welfare state and a genuine democracy with a rule of law and an independent judiciary."[15] Other ideas he has presented include a requirement of all students to spend a year after graduation teaching in the countryside and cutting down the over-staffed bureaucracy in order to send them to teach too.[36] "We need decentralisation, empowering people at the grass roots," he has said.[46] In June 2007, Khan publicly deplored Britain for knighting Indian-born author Salman Rushdie. He said, "Western civilisation should have been mindful of the injury the writer had caused to the Muslim community by writing his highly controversial book, The Satanic Verses."[47]

Criticism

During the 1970s and 1980s, Khan became known as a socialite due to his "non-stop partying" at London nightclubs such as Annabel's and Tramp. though he claims to have hated English pubs and never drank alcohol.[3][7][24][34] He also gained notoriety in London gossip columns for romancing young debutantes such as Susannah Constantine, Lady Liza Campbell and the artist Emma Sergeant.[7]

In 1995, despite a marriage to British socialite Jemima Goldsmith, he denounced the west with "its fat women in miniskirts," and called for Pakistanis to seek home-grown political solutions.[48] Khan is often dismissed as a political lightweight[41] and a celebrity outsider in Pakistan,[16] where national newspapers also refer to him as a "spoiler politician".[49] Muttahida Qaumi Movement, a political party, has asserted that Khan is "a sick person who has been a total failure in politics and is alive just because of the media coverage".[50] The Political observers say the crowds he draws are attracted by his cricketing celebrity, and the public has been reported to view him as a figure of entertainment rather than a serious political authority.[36] His failure to gain political power or build a national support base is ascribed, by commentators and observers, to Khan's lack of political maturity and naivete.[24] Newspaper columnist Ayaz Amir told the American Washington Post: "[Khan] doesn't have that political thing which sets bellies on fire."

The Guardian newspaper in England described Khan as a "miserable politician," observing that, "Khan's ideas and affiliations since entering politics in 1996 have swerved and skidded like a rickshaw in a rainshower... He preaches democracy one day but gives a vote to reactionary mullahs the next."[35] The charge constantly raised against Khan is that of hypocrisy and opportunism, including what has been called his life's "playboy to puritan U-turn."[16] One of Pakistan's most respected political commentators, Najam Sethi, stated that, "A lot of the Imran Khan story is about backtracking on a lot of things he said earlier, which is why this doesn’t inspire people."[16] Khan's political flip-flops consist of his vocal criticism of President Musharraf after having supported his military takeover in 1999. Similarly, Khan was a critic of former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif when Sharif was in power, having said at the time: "Our current prime minister has a fascist mind-set, and members of parliament cannot go against the ruling party. We think that every day he stays in power, the country is sinking more into anarchy."[51] Yet, he joined forces with Sharif in 2008 against Musharraf. In a column entitled "Will the Real Imran Please Stand Up," Pakistani columnist Amir Zia quoted one of PTI's Karachi-based leaders as saying, "Even we are finding it difficult to figure out the real Imran. He dons the shalwar-kameez and preaches desi and religious values while in Pakistan, but transforms himself completely while rubbing shoulders with the elite in Britain and elsewhere in the west."[52]

In 2008, as part of the Hall of Shame awards for 2007, Pakistan's Newsline magazine gave Khan the "Paris Hilton award for being the most undeserving media darling." The 'citation' for Khan read: "He is the leader of a party that is the proud holder of one National Assembly seat (and) gets media coverage inversely proportional to his political influence." The Guardian has described the coverage garnered by Khan's post-retirement activities in England, where he made his name as a cricket star and a night-club regular, as "terrible tosh, with danger attached. It turns a great (and greatly miserable) Third World nation into a gossip-column annex. We may all choke on such frivolity."[53] After the 2008 general elections, political columnist Azam Khalil addressed Khan, who remains respected as a cricket legend, as one of the "utter failures in Pakistani politics".[54] Writing in the Frontier Post, Khalil added: "Imran Khan has time and again changed his political course and at present has no political ideology and therefore was not taken seriously by a vast majority of the people."

Awards and honours

In 1992, Khan was given Pakistan's civil award, the Hilal-i-Imtiaz. He had received the President’s Pride of Performance Award in 1983. Khan is featured in the University of Oxford's Hall of Fame and has been an honorary fellow of Oxford's Keble College.[29] On 7 December 2005, Khan was appointed the fifth Chancellor of the University of Bradford, where he is also a patron of the Born in Bradford research project.

In 1976 as well as 1980, Khan was awarded The Cricket Society Wetherall Award for being the leading all-rounder in English first-class cricket. He was also named Wisden Cricketer of the Year in 1983, Sussex Cricket Society Player of the Year in 1985, and the Indian Cricket Cricketer of the Year in 1990.[12] Khan is currently placed at Number 8 on the all-time list of the ESPN Legends of Cricket. On 5 July 2008, he was one of several veteran Asian cricketers presented special silver jubilee awards at the inaugural Asian cricket Council (ACC) award ceremony in Karachi.[55]

On 8 July 2004, Khan was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2004 Asian Jewel Awards in London, for "acting as a figurehead for many international charities and working passionately and extensively in fund-raising activities.[56] On 13 December 2007, Khan received the Humanitarian Award at the Asian Sports Awards in Kuala Lumpur for his efforts in setting up the first cancer hospital in Pakistan.[57] In 2009, at International Cricket Council's centennial year celebration, Khan was one of fifty-five cricketers inducted into the ICC Hall of Fame.[58]

Writings by Khan

Khan occasionally contributes opinion editorials on cricket and Pakistani politics to British newspapers. He has also published five works of non-fiction, including an autobiography co-written with Patrick Murphy. It was disclosed in 2008 that Khan did not write his second book, Indus Journey: A Personal View of Pakistan. Instead, his the book's publisher Jeremy Lewis revealed in a memoir that he had to write the book for Khan. Lewis recalls that when he asked Khan to show his writing for publication, "he handed me a leatherbound notebook or diary containing a few jottings and autobiographical snippets. It took me, at most, five minutes to read them; and that, it soon became apparent, was all we had to go on."[59]

Books

- Khan, Imran (1989). Imran Khan's cricket skills. London : Golden Press in association with Hamlyn. ISBN 0600563499.

- Khan, Imran & Murphy, Patrick (1983). Imran: The autobiography of Imran Khan. Pelham Books. ISBN 0720714893.

- Khan, Imran (1991). Indus Journey: A Personal View of Pakistan. Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0701135271.

- Khan, Imran (1992). All Round View. Mandarin. ISBN 0749314990.

- Khan, Imran (1993). Warrior Race: A Journey Through the Land of the Tribal Pathans. Chatto Windus. ISBN 0701138904.

Articles

- Guardian comments, political and cricket commentary by Khan

- Telegraph columns, sports articles penned by Khan from 2000 to present

- We must address the root causes of this terror, Khan's editorial in the Independent following the 11 September attacks

- Benazir Bhutto has only herself to blame, Khan's 2007 editorial on Bhutto's return to Pakistan

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 "Imran Khan". Overseas Pakistanis Foundation. http://www.opf.org.pk/almanac/S/sports.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ "Pakistan legend Imran Khan inducted into ICC Cricket Hall of Fame". Thesportscampus.com. http://www.thesportscampus.com/201007146222/test-cricket/former-pakistan-great-imran-khan-inducted-into-icc-cricket-hall-of-fame. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Kervin, Alison (2006-08-06). "Imran Khan: ‘What I do now fulfils me like never before’". London: The Sunday Times. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/sport/article601339.ece. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Pakistan MPs in election boycott". BBC. 2007-10-02. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/7023424.stm. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Khan, Imran (1993). Warrior Race. London: Butler & Tanner Ltd. ISBN 0701138904.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ali, Syed Hamad (2008-07-23). "Pakistan's Dreamer". New Statesman. http://www.newstatesman.com/asia/2008/07/imran-khan-pakistan-university. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 Adams, Tim (2006-07-02). "The path of Khan". London: The Observer. http://observer.guardian.co.uk/osm/story/0,,1807210,00.html. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "The Interview: Anything he Khan't do?". The Oxford Student. 1999. http://www.oxfordstudent.com/tt1999wk5/News/the_interview:_anything_he_khan't_do%3F. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ "Profiles:Jemima Khan". Hello!. http://www.hellomagazine.com/profiles/jemimakhan/. Retrieved 2007-10-08.

- ↑ Goldsmith, Annabel (2004). Annabel: An Unconventional Life: The Memoirs of Lady Annabel Goldsmith. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-82966-1.

- ↑ "Imran Khan and Jemima divorce". BBC. 2004-06-22. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/3829383.stm. Retrieved 2007-10-05.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 "Imran Khan". CricketArchive. http://cricketarchive.com/Archive/Players/1/1383/1383.html. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ "ICC Player Rankings". ICC. http://www.iccreliancerankings.com/alltime/test/bowling/. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ↑ Basevi, Travis (2005-10-11). "Best averages by batting position". Cricinfo. http://content-aus.cricinfo.com/ci/content/story/221606.html. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Farndale, Nigel (2007-08-14). "Imran Khan is ready to become political force". London: The Sunday Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2007/08/12/nrkhan112.xml. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 "Pakistan - Imran Khan". ABC. 2006-05-23. http://www.abc.net.au/foreign/content/2006/s1647595.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Imran: Wrong time to tour". BBC. 2001-05-01. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport2/low/in_depth/2001/england_v_pakistan/1295868.stm. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ Rashid, Ahmed (1992-03-28). "Cricket: Guns and roses for Pakistan". The Independent.

- ↑ "Cricket's sharp practice". BBC. 2003-05-21. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport2/hi/cricket/1665008.stm. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Botham, Lamb end legal battle". BBC. 1999-05-20. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/348740.stm. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ "Sports: opinion". Outlook magazine. http://www.outlookindia.com/author.asp?id=section&name=Imran+Khan§ion=Sports. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ Khan, Imran (2003-01-24). "Who's the real villain?". London: The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/sport/2003/jan/24/cricket.iraq. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ "Another poor batting display". BBC. 2003-02-25. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport3/cwc2003/hi/newsid_2790000/newsid_2799100/2799123.stm. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 Lancaster, John (2005-07-04). "A Pakistani Cricket Star's Political Move". Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/07/03/AR2005070301078.html. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ "Big Time cricket on small screen". Financial Express. 2004-03-03.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Unmatched Coverage of India-Pakistan Test Cricket on Sify.com". Business Wire. 2005-03-09.

- ↑ "Imran Khan has emergency surgery". BBC News. 2009-11-10. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/cricket/other_international/pakistan/8352170.stm. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ↑ http://www.shaukatkhanum.org.pk/about-us/history.html

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Mr Imran Khan's Statement". World Health Organization. http://www.emro.who.int/tfi/wntd2002/WNTD2002Kit-Khan.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ "UNICEF and the stars". unicef.org. http://www.unicef.org/sowc96/kstars.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ "University delegation goes east to establish new College". University of Bradford. 2006-02-22. http://www.brad.ac.uk/admin/pr/pressreleases/2006/delegation.php. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ Vijh, Surekha (1996-12-27). "Cricket star sets sights on Pakistan's presidency". The Washington Times.

- ↑ Press Trust Of India (2008-01-21). "Imran Khan, Musharraf bag 'Hall of Shame' awards". Hindustan Times. http://www.hindustantimes.com/StoryPage/StoryPage.aspx?sectionName=&id=f2acc1c9-88ef-4a75-9432-770a01be51ad&MatchID1=4726&TeamID1=2&TeamID2=3&MatchType1=1&SeriesID1=1191&PrimaryID=4726&Headline=Imran%2c+Pervez+bag+'Hall+of+Shame'+awards&strParent=strParentID. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Forsyth, James (2005-05-31). "Khan Artist". The Weekly Standard. http://www.weeklystandard.com/Content/Public/Articles/000/000/005/658vhcpk.asp?pg=1. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Walsh, Delcan (2005-08-31). "'When you speak out, people react'". London: The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/sport/2005/aug/31/cricket.pakistan. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 "Imran Khan Standing for Election Again". Guardian Unlimited. 2002-09-26. http://www.buzzle.com/editorials/9-26-2002-27111.asp. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ Lancaster, John (2002-11-16). "Pakistan's parliament sworn, after 3 years". United Press International. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P1-69595658.html. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ↑ "Candidate details: Imran Khan". Pakistan Elections. http://www.elections.com.pk/candidatedetails.php?id=72. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ "EC rejects references against Imran Khan". Associated Press of Pakistan. 2007-09-05. http://www.app.com.pk/en/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=15979&Itemid=2. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ "Imran Khan escapes from house arrest". The Times of India. 2007-11-05. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/World/Imran_Khan_escapes_from_house_arrest/articleshow/2517638.cms. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Page, Jeremy (2007-11-14). "Imran Khan comes out of hiding to lead students in street protests". London: The Times. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/asia/article2866163.ece. Retrieved 2007-11-15.

- ↑ Page, Jeremy (2007-11-14). "Imran Khan faces terror charges after arrest in Pakistan". London: Times Online. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/asia/article2868571.ece. Retrieved 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Imran eating bread, eggs and fruit: jail official". Daily Times. 2007-11-21. http://www.dailytimes.com.pk/default.asp?page=2007%5C11%5C21%5Cstory_21-11-2007_pg7_3. Retrieved 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Imran Khan released from prison". BBC. 2007-11-21. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/7105973.stm. Retrieved 2007-10-05.

- ↑ "Imran Khan's party issues election manifesto". Radio Pakistan.

- ↑ "Imran Khan's new game". BBC. 1998-07-09. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/128794.stm. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ Lancaster, John (2007-06-17). "Imran has problems with fatwa-hit Rushdie's knighthood". himtimes.com. http://www.himtimes.com/india/india.php?subaction=showfull&id=1182180098. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ http://www.weeklystandard.com/Content/Public/Articles/000/000/005/658vhcpk.asp

- ↑ Khalil, Azam (2008-09-08). "A New Era". Frontier Post.

- ↑ "A "totally failed" politician Imran surviving on media glare, says MQM". Asian News International. 2008-05-23.

- ↑ Boustany, Nora (1999-09-15). "Ex-Cricket Star Won't Play Islamabad's Game". Washington Post.

- ↑ Zia, Amir. "Will the Real Imran Please Stand Up". Newsline. http://www.newsline.com.pk/NewsDec2002/newsbeatdec5.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ Preston, Peter (1996-11-22). "Just imagine it: Imran Khan as Premier". The Guardian.

- ↑ Khalil, Azam. "Politics of boycott". Frontier Post. http://www.thefrontierpost.com/News.aspx?ncat=ar&nid=204. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ↑ "Tendulkar honoured with best Asian ODI batsman award by ACC". Hindustan Times. 2008-07-06. http://www.hindustantimes.com/StoryPage/StoryPage.aspx?id=55160544-320b-4723-8ca9-14b5063fb544&ParentID=52c6b1a7-aaed-4d36-811f-eea832a76f24&MatchID1=4726&TeamID1=2&TeamID2=3&MatchType1=1&SeriesID1=1191&PrimaryID=4726&Headline=Sachin+adjudged+best+Asian+ODI+batsman. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ↑ "Former Cricketer Imran Khan is an Asian jewel". 2004-07-09. http://www.redhotcurry.com/archive/news/2004/jewel_awards2004_southern.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ "Asian Awards". Hindustan Times. 2007-12-13. http://www.hindustantimes.com/StoryPage/StoryPage.aspx?id=fc2d1dd8-df34-4ba0-9e47-58f92b1f4c3d&MatchID1=4576&TeamID1=8&TeamID2=2&MatchType1=1&SeriesID1=1147&MatchID2=4614&TeamID3=1&TeamID4=5&MatchType2=2&SeriesID2=1161&PrimaryID=4576&Headline=Indian+tennis+legend+gets+top+Asian+honour. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ↑ "Hall of Famers / ICC Centenary". 2004-07-09. http://www.catchthespirit.com/hall_of_fame/hall_of_famers.aspx. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- ↑ "It's a miracle... Imran's notes turn into book". Evening Standard. 2008-07-04.

Further reading

- Tennant, Evo (1996). Imran Khan. Trafalgar Square. ISBN 0575059362.

External links

- Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, Khan's political party

- Imran Khan - Chancellor, homepage at the University of Bradford

- An Intimate Encounter, interview with Khan by Dapne Barak

- Imran Khan interviewed by Mehdi Hasan on New Statesman.

| Sporting positions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Zaheer Abbas Zaheer Abbas Abdul Qadir |

Pakistan Cricket Captain 1982–1983 1985–1987 1989–1992 |

Succeeded by Sarfraz Nawaz Abdul Qadir Javed Miandad |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Party created |

Chairman of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf 1996–present |

Succeeded by Incumbent |

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by Baroness Lockwood |

Chancellor of the University of Bradford 2005–present |

Succeeded by Incumbent |

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||