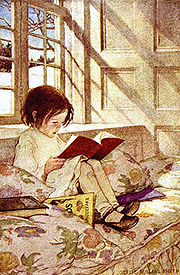

Illustration

An illustration is a visualization such as a drawing, painting, photograph or other work of art that is created (usually in the form of a work made for hire) to elucidate or decorate textual information (such as a story, poem or newspaper article) by providing a visual representation.

Contents |

History

Early history

The earliest forms of illustration were prehistoric cave paintings. Before the invention of the printing press, books were hand-illustrated. Illustration has been used in China and Japan since the 8th century, traditionally by creating woodcuts to accompany writing.

15th century through 18th century

During the 15th century, books illustrated with woodcut illustrations became available. The main processes used for reproduction of illustrations during the 16th and 17th centuries were engraving and etching. At the end of the 18th century, lithography allowed even better illustrations to be reproduced. The most notable illustrator of this epoch was William Blake who rendered his illustrations in the medium of relief etching.

Early to mid 19th century

Notable figures of the early century were John Leech, George Cruikshank, Dickens' illustrator Hablot Knight Browne and, in France, Honoré Daumier. The same illustrators would contribute to satirical and straight-fiction magazines, but in both cases the demand was for character-drawing which encapsulated or caricatured social types and classes.

The British humorous magazine Punch, which was founded in 1841 riding on the earlier success of Cruikshank's Comic Almanac (1827-1840), employed an uninterrupted run of high-quality comic illustrators, including Sir John Tenniel, the Dalziel Brothers and Georges du Maurier, into the 20th century. It chronicles the gradual shift in popular illustration from reliance on caricature to sophisticated topical observations. These artists all trained as conventional fine-artists, but achieved their reputations primarily as illustrators. Punch and similar magazines such as the Parisian Le Voleur realised that good illustrations sold as many copies as written content.

Golden age of illustration

The American "golden age of illustration" lasted from the 1880s until shortly after World War I (although the active career of several later "golden age" illustrators went on for another few decades). As in Europe a few decades earlier, newspapers, mass market magazines, and illustrated books had become the dominant media of public consumption. Improvements in printing technology freed illustrators to experiment with color and new rendering techniques. A small group of illustrators in this time became rich and famous. The imagery they created was a portrait of American aspirations of the time.

A prolific artist who linked the earlier and later 19th century in Europe was Gustave Doré. His sombre illustrations of London poverty in the 1860s were influential examples of social commentary in art. Edmund Dulac, Arthur Rackham, Walter Crane and Kay Nielsen were notable representatives of this style, which often carried an ethos of neo-mediævalism and took mythological and fairy-tale subjects. By contrast the English illustrator Beatrix Potter based her colored children's illustrations on accurate naturalistic observation of animal-life.

The opulence and harmony of the work of the "golden age" illustrators was counterpointed in the 1890s by artists like Aubrey Beardsley who reverted to a sparser black-and-white style influenced by woodcut and silhouette, anticipating Art Nouveau, and Les Nabis. American illustration of this period was anchored by the Brandywine Valley tradition, begun by Howard Pyle and carried on by his students, who included N.C. Wyeth, Maxfield Parrish, Jesse Willcox Smith and Frank Schoonover.

A movement was started in Latin America by Santiago Martinez Delgado who worked in the 1930s for Esquire Magazine while an art student in Chicago, and later in his native Colombia with the Vida Magazine, Martinez a disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright worked in the Art Deco style. Also in the 1930s the influence of propaganda art and expressionism was felt in the work of the British freelance illustrator Arthur Wragg. His stylised monotone shapes suggested the block-printing techniques used for political posters, but by this time the technology of transferring artwork to printing plates by photographic means had advanced to the extent that Wragg could produce all his work in pen and ink.

Technical illustration

Technical illustration is the use of illustration to visually communicate information of a technical nature. Technical illustrations can be component technical drawings or diagrams. Technical illustration in general aim "to generate expressive images that effectively convey certain information via the visual channel to the human observer".[1]

Technical illustration generally have to describe and explain the subjects to a nontechnical audience. Therefore the visual image should be accurate in terms of dimensions and proportions, and should provide "an overall impression of what an object is or does, to enhance the viewer’s interest and understanding".[2]

Illustration art

Today, there is a growing interest in collecting and admiring original artwork that was used as illustrations in books, magazines, posters, etc. Various museum exhibitions, magazines and art galleries have devoted space to the illustrators of the past.

In the visual art world, illustrators have sometimes been considered less important in comparison with fine artists and graphic designers. But as the result of computer game and comic industry growth, illustrations are becoming valued as popular and profitable art works that can acquire a wider market than the other two, especially in Korea, Japan, Hong Kong and USA.

See also

- Archaeological illustration

- Art gallery

- Book illustration

- Concept art

- Communication design

- Graphic design

- Illustrators

- Image development

- Information graphics

- Posters

- Technical illustration

References

- ↑ Ivan Viola and Meister E. Gröller (2005). "Smart Visibility in Visualization". In: Computational Aesthetics in Graphics, Visualization and Imaging. L. Neumann et al. (Ed.)

- ↑ www.industriegrafik.com website, Last modified: Juni 15, 2002. Accessed 15 feb 2009.

|

||||||||||||||