Hypothalamus

| Brain: Hypothalamus | ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

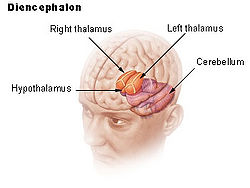

| Location of the human hypothalamus | ||

|

||

| Diencephalon | ||

| Latin | hypothalamus | |

| Gray's | subject #189 812 | |

| NeuroNames | hier-358 | |

| MeSH | Hypothalamus | |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_734 | |

The hypothalamus (from Greek ὑπό = under and θάλαμος = room, chamber) is a portion of the brain that contains a number of small nuclei with a variety of functions. One of the most important functions of the hypothalamus is to link the nervous system to the endocrine system via the pituitary gland (hypophysis).

The hypothalamus is located below the thalamus, just above the brain stem. In the terminology of neuroanatomy, it forms the ventral part of the diencephalon. All vertebrate brains contain a hypothalamus. In humans, it is roughly the size of an almond.

The hypothalamus is responsible for certain metabolic processes and other activities of the autonomic nervous system. It synthesizes and secretes certain neurohormones, often called hypothalamic-releasing hormones, and these in turn stimulate or inhibit the secretion of pituitary hormones. The hypothalamus controls body temperature, hunger, thirst,[1] fatigue, and circadian cycles.

Contents |

Inputs

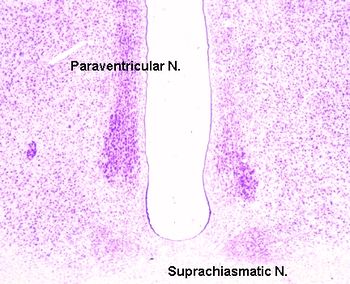

The hypothalamus is a complex region in the brain of humans, and even small nuclei within the hypothalamus are involved in many different functions. The paraventricular nucleus for instance makes oxytocin and the supraoptic nucleus makes vasopressin (also called antidiuretic hormone) neurons which project to the posterior pituitary, but also contains neurons that regulate ACTH and TSH secretion from the anterior pituitary, as well as gastric reflexes, maternal behavior, blood pressure, feeding, immune responses, and temperature.

The hypothalamus co-ordinates many hormonal and behavioural circadian rhythms, complex patterns of neuroendocrine outputs, complex homeostatic mechanisms,[2] and many important behaviours.

The hypothalamus must therefore respond to many different signals, some of which are generated externally and some internally. It is thus richly connected with many parts of the central nervous system, including the brainstem reticular formation and autonomic zones, the limbic forebrain (particularly the amygdala, septum, diagonal band of Broca, and the olfactory bulbs, and the cerebral cortex).

The hypothalamus is responsive to:

- Light: daylength and photoperiod for regulating circadian and seasonal rhythms

- Olfactory stimuli, including pheromones

- Steroids, including gonadal steroids and corticosteroids

- Neurally transmitted information arising in particular from the heart, the stomach, and the reproductive tract

- Autonomic inputs

- Blood-borne stimuli, including leptin, ghrelin, angiotensin, insulin, pituitary hormones, cytokines, plasma concentrations of glucose and osmolarity etc.

- Stress

- Invading microorganisms by increasing body temperature, resetting the body's thermostat upward.

Olfactory stimuli

Olfactory stimuli are important for sex and neuroendocrine function in many species. For instance if a pregnant mouse is exposed to the urine of a 'strange' male during a critical period after coitus then the pregnancy fails (the Bruce effect). Thus during coitus, a female mouse forms a precise 'olfactory memory' of her partner which persists for several days. Pheromonal cues aid synchronisation of oestrus in many species; in women, synchronised menstruation may also arise from pheromonal cues, although the role of pheromones in humans is doubted by many.

Blood-borne stimuli

Peptide hormones have important influences upon the hypothalamus, and to do so they must evade the blood-brain barrier. The hypothalamus is bounded in part by specialized brain regions that lack an effective blood-brain barrier; the capillary endothelium at these sites is fenestrated to allow free passage of even large proteins and other molecules. Some of these sites are the sites of neurosecretion - the neurohypophysis and the median eminence. However others are sites at which the brain samples the composition of the blood. Two of these sites, the subfornical organ and the OVLT (organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis) are so-called circumventricular organs, where neurons are in intimate contact with both blood and CSF. These structures are densely vascularized, and contain osmoreceptive and sodium-receptive neurons which control drinking, vasopressin release, sodium excretion, and sodium appetite. They also contain neurons with receptors for angiotensin, atrial natriuretic factor, endothelin and relaxin, each of which is important in the regulation of fluid and electrolyte balance. Neurons in the OVLT and SFO project to the supraoptic nucleus and paraventricular nucleus, and also to preoptic hypothalamic areas. The circumventricular organs may also be the site of action of interleukins to elicit both fever and ACTH secretion, via effects on paraventricular neurons.

It is not clear how all peptides that influence hypothalamic activity gain the necessary access. In the case of prolactin and leptin, there is evidence of active uptake at the choroid plexus from blood into CSF. Some pituitary hormones have a negative feedback influence upon hypothalamic secretion; for example, growth hormone feeds back on the hypothalamus, but how it enters the brain is not clear. There is also evidence for central actions of prolactin and TSH.

The hypothalamus functions as a type of thermostat for the body.[3] It sets a desired body temperature, and stimulates either heat production and retention to raise the blood temperature to a higher setting, or sweating and vasodilation to cool the blood to a lower temperature. All fevers result from a raised setting in the hypothalamus; elevated body temperatures due to any other cause are classified as hyperthermia.[3] Rarely, direct damage to the hypothalamus, such as from a stroke, will cause a fever; this is sometimes called a hypothalamic fever. However, it is more common for such damage to cause abnormally low body temperatures.[3]

Steroids

The hypothalamus contains neurons that react strongly to steroids and glucocorticoids – (the steroid hormones of the adrenal gland, released in response to ACTH). It also contains specialised glucose-sensitive neurons (in the arcuate nucleus and ventromedial hypothalamus), which are important for appetite. The preoptic area contains thermosensitive neurons; these are important for TRH secretion.

Neural inputs

The hypothalamus receives many inputs from the brainstem; notably from the nucleus of the solitary tract, the locus coeruleus, and the ventrolateral medulla. Oxytocin secretion in response to suckling or vagino-cervical stimulation is mediated by some of these pathways; vasopressin secretion in response to cardiovascular stimuli arising from chemoreceptors in the carotid body and aortic arch, and from low-pressure atrial volume receptors, is mediated by others. In the rat, stimulation of the vagina also causes prolactin secretion, and this results in pseudo-pregnancy following an infertile mating. In the rabbit, coitus elicits reflex ovulation. In the sheep, cervical stimulation in the presence of high levels of estrogen can induce maternal behavior in a virgin ewe. These effects are all mediated by the hypothalamus, and the information is carried mainly by spinal pathways that relay in the brainstem. Stimulation of the nipples stimulates release of oxytocin and prolactin and suppresses the release of LH and FSH.

Cardiovascular stimuli are carried by the vagus nerve, but the vagus also conveys a variety of visceral information, including for instance signals arising from gastric distension to suppress feeding. Again this information reaches the hypothalamus via relays in the brainstem.

Nuclei

A cross section of the monkey hypothalamus displays 2 of the major hypothalamic nuclei on either side of the fluid-filled 3rd ventricle

The hypothalamic nuclei include the following:[4][5][6]

| Region | Area | Nucleus | Function[7] |

| Anterior | Medial | Medial preoptic nucleus |

|

| Supraoptic nucleus (SO) |

|

||

| Paraventricular nucleus (PV) |

|

||

| Anterior hypothalamic nucleus (AH) |

|

||

| Suprachiasmatic nucleus (SC) |

|

||

| Lateral | Lateral preoptic nucleus | ||

| Lateral nucleus (LT) |

|

||

| Part of supraoptic nucleus (SO) |

|

||

| Tuberal | Medial | Dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus (DM) |

|

| Ventromedial nucleus (VM) |

|

||

| Arcuate nucleus (AR) |

|

||

| Lateral | Lateral nucleus (LT) |

|

|

| Lateral tuberal nuclei | |||

| Posterior | Medial | Mammillary nuclei (part of mammillary bodies) (MB) | |

| Posterior nucleus (PN) |

|

||

| Lateral | Lateral nucleus (LT) |

- See also: ventrolateral preoptic nucleus

Hypothalamic nuclei on one side of the hypothalamus, shown in a 3-D computer reconstruction

Outputs

The outputs of the hypothalamus can be divided into two categories: neural projections, and endocrine hormones.[9]

Neural projections

Most fiber systems of the hypothalamus run in two ways (bidirectional).

- Projections to areas caudal to the hypothalamus go through the medial forebrain bundle, the mammillotegmental tract and the dorsal longitudinal fasciculus.

- Projections to areas rostral to the hypothalamus are carried by the mammillothalamic tract, the fornix and terminal stria.

- Projections to areas of the sympathetic motor system (lateral horn spinal segments T1-L2/L3 of the) are carried by the hypothalamospinal tract and they activate the sympathetic motor pathway

Endocrine hormones

The hypothalamus affects the endocrine system and governs emotional behavior, such as anger and sexual activity. Most of the hypothalamic hormones generated are distributed to the pituitary via the hypophyseal portal system.[10] The hypothalamus maintains homeostasis; this includes a regulation of blood pressure, heart rate, and temperature.

| Secreted hormone | Abbreviation | Produced by | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (Prolactin-releasing hormone) |

TRH, TRF, or PRH | Parvocellular neurosecretory neurons | Stimulate thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) release from anterior pituitary (primarily) Stimulate prolactin release from anterior pituitary |

| Dopamine (Prolactin-inhibiting hormone) |

DA or PIH | Dopamine neurons of the arcuate nucleus | Inhibit prolactin release from anterior pituitary |

| Growth hormone-releasing hormone | GHRH | Neuroendocrine neurons of the Arcuate nucleus | Stimulate Growth hormone (GH) release from anterior pituitary |

| Somatostatin (growth hormone-inhibiting hormone) |

SS, GHIH, or SRIF | Neuroendocrine cells of the Periventricular nucleus | Inhibit Growth hormone (GH) release from anterior pituitary Inhibit thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) release from anterior pituitary |

| Gonadotropin-releasing hormone | GnRH or LHRH | Neuroendocrine cells of the Preoptic area | Stimulate follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) release from anterior pituitary Stimulate luteinizing hormone (LH) release from anterior pituitary |

| Corticotropin-releasing hormone | CRH or CRF | Parvocellular neurosecretory neurons | Stimulate adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) release from anterior pituitary |

| Oxytocin | Magnocellular neurosecretory cells | Uterine contraction Lactation (letdown reflex) |

|

| Vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone) |

ADH or AVP | Magnocellular neurosecretory neurons | Increases water permeability in the distal convoluted tubule and collecting duct of nephrons, thus promoting water reabsorption and increasing blood volume |

See also: Hypocretin

Control of food intake

The extreme lateral part of the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus is responsible for the control of food intake. Stimulation of this area causes increased food intake. Bilateral lesion of this area causes complete cessation of food intake. Medial parts of the nucleus have a controlling effect on the lateral part. Bilateral lesion of the medial part of the ventromedial nucleus causes hyperphagia and obesity of the animal. Further lesion of the lateral part of the ventromedial nucleus in the same animal produces complete cessation of food intake.

There are different hypotheses related to this regulation:[11]

- Lipostatic hypothesis - this hypothesis holds that adipose tissue produces a humoral signal that is proportionate to the amount of fat and acts on the hypothalamus to decrease food intake and increase energy output. It has been evident that a hormone leptin acts on the hypothalamus to decrease food intake and increase energy output.

- Gutpeptide hypothesis - gastrointestinal hormones like Grp, glucagons, CCK and others claimed to inhibit food intake. The food entering the gastrointestinal tract triggers the release of these hormones which acts on the brain to produce satiety. The brain contains both CCK-A and CCK-B receptors.

- Glucostatic hypothesis - the activity of the satiety center in the ventromedial nuclei is probably governed by the glucose utilization in the neurons. It has been postulated that when their glucose utilization is low and consequently when the arteriovenous blood glucose difference across them is low, the activity across the neurons decrease. Under these conditions, the activity of the feeding center is unchecked and the individual feels hungry. Food intake is rapidly increased by intraventricular administration of 2-deoxyglucose therefore decreasing glucose utilization in cells.

- Thermostatic hypothesis - according to this hypothesis, a decrease in body temperature below a given set point stimulates appetite, while an increase above the set point inhibits appetite.

Sexual dimorphism

Several hypothalamic nuclei are sexually dimorphic, i.e. there are clear differences in both structure and function between males and females.

Some differences are apparent even in gross neuroanatomy: most notable is the sexually dimorphic nucleus within the preoptic area, which is present only in males. However most of the differences are subtle changes in the connectivity and chemical sensitivity of particular sets of neurons.

The importance of these changes can be recognised by functional differences between males and females. For instance, males of most species prefer the odor and appearance of females over males, which is instrumental in stimulating male sexual behavior. If the sexually dimorphic nucleus is lesioned, this preference for females by males diminishes. Also, the pattern of secretion of growth hormone is sexually dimorphic, and this is one reason why in many species, adult males are much larger than females.

Responses to ovarian steroids

Other striking functional dimorphisms are in the behavioral responses to ovarian steroids of the adult. Males and females respond differently to ovarian steroids, partly because the expression of estrogen-sensitive neurons in the hypothalamus is sexually dimorphic, i.e. estrogen receptors are expressed in different sets of neurons.

Estrogen and progesterone can influence gene expression in particular neurons or induce changes in cell membrane potential and kinase activation, leading to diverse non-genomic cellular functions. Estrogen and progesterone bind to their cognate nuclear hormone receptors, which translocate to the cell nucleus and interact with regions of DNA known as hormone response elements (HREs) or get tethered to another transcription factor's binding site. Estrogen receptor (ER) has been shown to transactivate other transcription factors in this manner, despite the absence of an estrogen response element (ERE) in the proximal promoter region of the gene. ERs and progesterone receptors (PRs) are generally gene activators, with increased mRNA and subsequent protein synthesis following hormone exposure.

Male and female brains differ in the distribution of estrogen receptors, and this difference is an irreversible consequence of neonatal steroid exposure. Estrogen receptors (and progesterone receptors) are found mainly in neurons in the anterior and mediobasal hypothalamus, notably:

- the preoptic area (where LHRH neurons are located)

- the periventricular nucleus (where somatostatin neurons are located)

- the ventromedial hypothalamus (which is important for sexual behavior).

Gonadal steroids in neonatal life of rats

In neonatal life, gonadal steroids influence the development of the neuroendocrine hypothalamus. For instance, they determine the ability of females to exhibit a normal reproductive cycle, and of males and females to display appropriate reproductive behaviors in adult life.

- If a female rat is injected once with testosterone in the first few days of postnatal life (during the "critical period" of sex-steroid influence), the hypothalamus is irreversibly masculinized; the adult rat will be incapable of generating an LH surge in response to estrogen (a characteristic of females), but will be capable of exhibiting male sexual behaviors (mounting a sexually receptive female).

- By contrast, a male rat castrated just after birth will be feminized, and the adult will show female sexual behavior in response to estrogen (sexual receptivity, lordosis behavior).

Androgens in primates

In primates, the developmental influence of androgens is less clear, and the consequences are less understood. Within the brain, testosterone is aromatized to (estradiol), which is the principal active hormone for developmental influences. The human testis secretes high levels of testosterone from about week 8 of fetal life until 5–6 months after birth (a similar perinatal surge in testosterone is observed in many species), a process that appears to underlie the male phenotype. Estrogen from the maternal circulation is relatively ineffective, partly because of the high circulating levels of steroid-binding proteins in pregnancy.

Human sexual orientation and the hypothalamus

According to D.F. Swaab, "Neurobiological research related to sexual orientation in humans is only just gathering momentum, but the evidence already shows that humans have a vast array of brain differences, not only in relation to gender, but also in relation to sexual orientation."[12]

Swaab first reported on the relationship between sexual orientation in males and the hypothalamus's "clock", the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). In 1990, Swaab and Hofman[13] reported that the SCN of heterosexual men was significantly larger than in women, and the SCN of homosexual men was signifigantly larger than in heterosexual men. Then in 1995, Swaab et al.[14] linked brain development to sexual orientation by treating male rats both pre- and postnatally with ATD, an aromatase blocker in the brain. This produced an enlarged SCN and bisexual behavior in the adult male rats. In 1991, LeVay showed that part of the sexually dimorphic nucleus (SDN), the interstitial nuclei of the anterior hypothalamus (INAH) 3, is twice as large in HeM as HoM and HeW, in terms of volume but not number of neurons.

In 2004 and 2006, two studies by Berglund, Lindström, and Savic[15][16] used Positron Emission Tomography (PET) to observe how the hypothalamus responds to smelling common odors, the scent of testosterone found in male sweat, and the scent of estrogen found in female urine. These studies showed that the hypothalamus of HeM and HoW both respond to estrogen. Also, the hypothalamus of HoM and HeW both respond to testosterone. The hypothalamus of all four groups did not respond to the common odors, which produced a normal olfactory response in the brain.

Other influences upon hypothalamic development

Sex steroids are not the only important influences upon hypothalamic development; in particular, pre-pubertal stress in early life determines the capacity of the adult hypothalamus to respond to an acute stressor.[17] Unlike gonadal steroid receptors, glucocorticoid receptors are very widespread throughout the brain; in the paraventricular nucleus, they mediate negative feedback control of CRF synthesis and secretion, but elsewhere their role is not well understood.

See also

- Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis)

- Neuroendocrinology

- John Leonora

Additional images

Median sagittal section of brain of human embryo of three months. |

Human brain left dissected midsagittal view |

References

- ↑ Definition of hypothalamus - NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms

- ↑ hypothalamus

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Fauci, Anthony, et al. (2008). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (17 ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 117–121. ISBN 9780071466332.

- ↑ Diagram of Nuclei (psycheducation.org)

- ↑ Diagram of Nuclei (universe-review.ca)

- ↑ Diagram of Nuclei (utdallas.edu)

- ↑ Unless else specified in table, then ref is: Guyton Eight Edition

- ↑ Walter F., PhD. Boron (2005). Medical Physiology: A Cellular And Molecular Approaoch. Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2328-3. Page 840

- ↑ Hypothalamus and ANS

- ↑ Overview of Hypothalamic and Pituitary Hormones

- ↑ Theologides A (1976). "Anorexia-producing intermediary metabolites". Am J Clin Nutr 29 (5): 552–8. PMID 178168.

- ↑ Swaab DF (2008). ""Sexual orientation and its basis in brain structure and function"". PNAS 105 (30): 10273–10274. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805542105. PMID 18653758.

- ↑ Swaab DF, Hofman MA (1990). "An enlarged suprachiasmatic nucleus in homosexual men". Brain Res. 537 (1-2): 141–8. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(90)90350-K. PMID 2085769.

- ↑ Swaab DF, Slob AK, Houtsmuller EJ, Brand T, Zhou JN (1995). "Increased number of vasopressin neurons in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of ‘bisexual’ adult male rats following perinatal treatment with the aromatase blocker ATD". Developmental Brain Research 85 (2): 273–279. doi:10.1016/0165-3806(94)00218-O. PMID 7600674.

- ↑ Savic I, Berglund H, Lindström P (2005). "Brain response to putative pheromones in homosexual men". PNAS 102 (20): 7356–7361. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407998102. PMID 15883379.

- ↑ Savic I, Berglund H, Lindström P (2006). "Brain response to putative pheromones in lesbian women". PNAS 103 (21): 8269–8274. doi:10.1073/pnas.0600331103. PMID 16705035.

- ↑ Romeo, Russell D; Rudy Bellani, Ilia N. Karatsoreos, Nara Chhua, Mary Vernov, Cheryl D. Conrad and Bruce S. McEwen (2005). "Stress History and Pubertal Development Interact to Shape Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Plasticity". Endocrinology (The Endocrine Society) 147 (4): 1664–1674. doi:10.1210/en.2005-1432. PMID 16410296. http://endo.endojournals.org/cgi/content/short/147/4/1664. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

Added Reference

de Vries, GJ, and Sodersten P (2009) Sex differences in the brain: the relation between structure and function. Hormones and Behavior 55:589-596.

External links

- BrainMaps at UCDavis Hypothalamus

- The Hypothalamus and Pituitary at endotexts.org

- NIF Search - Hypothalamus via the Neuroscience Information Framework

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||