Hussar

Hussar (pronounced /həˈzɑr/, /hʊˈzɑr/, or (spelling pronunciation) /həˈsɑr/; Serbian: husar, Hungarian: huszár, pronounced [huˈsaːr], plural huszárok; Polish: Husarz (heavy cavalry), Polish: Huzar (light cavalry); Slovak: Husár, Dutch: Huzaar, French: Hussard) refers to a number of types of light cavalry originated in Hungary.

Contents

|

History

The hussars of medieval Hungary

A type of irregular light horsemen was already well established by the 15th century in medieval Hungary.[1] Etymologists are divided over the derivation of the word 'hussar'.[2] Many scholars believe the word originated in Serbian[3] as 'Husar', derived from the Latin root 'cursus' meaning 'raid'.[2] According to Webster's the word hussar stems from the Hungarian huszár, which in turn originates from the Serbian хусар (Husar, or гусар, Gusar) meaning pirate, from the Medieval Latin cursarius (cf. the English word corsair).[4] A variant of this theory is offered by Byzantinist scholars, who argue the term originated in Roman military practice, and the cursarius--a group of fast moving horsemen used for scouting or raiding—came to be called tsanarioi in Greek or the Armenian Chosarioi.[5] Through Byzantine Army operations in the Balkans in the 10th and 11th centuries when Chosarioi/Chonsarioi were recruited with especially Serbs,[6] the word was subsequently reintroduced to Western European military practice after its original usage had been lost with the collapse of Rome in the west.[7] According to another theory, the word is derived from the Hungarian word of húsz meaning twenty, suggesting that hussar regiments were originally composed of twenty men.[2] Or the term huszár probably signified 'one in twenty' as selected for service by ballot.[8]

The hussars reportedly originated in bands of mostly Serbian warriors [9] crossing into southern Hungary after the Turkish invasion of Serbia at the end of the 14th century. The Governor of Hungary, Hunyadi János - John Hunyadi, created mounted units inspired by his enemy the Ottoman Turks. His son, Hunyadi Mátyás Matthias Corvinus, later king of Hungary, is unanimously accepted as the creator of these troops. Initially they fought in small bands, but were reorganised into larger, trained, formations during the reign of King Matthias I Corvinus of Hungary.[10][11] So the first Hussar regiments were the light cavalry of the Black Army of Hungary. Under his command the hussars took part in the war against the Ottoman Empire in 1485 and proved successful against the Turkish Spahis as well as against Bohemians and Poles. After the king's death in 1490, hussars remained the preferred form of cavalry in Hungary. The Habsburg emperors hired Hungarian hussars as mercenaries to serve against the Ottoman Empire and on various battlefields throughout Europe. The "father" of the US cavalry in 1777 was a Hungarian hussar named Kovács Mihály - Michael de Kovats.

Hussars of Frederick The Great

During and after the Rákóczi's War for Independence, many Hungarians served in the Habsburg army. Located in garrisons far away from Hungary, some deserted from the Austrian army joining that of Prussia. The value of the Hungarian hussars as light cavalry was recognised and in 1721 two Hussaren Corps were organised in the Prussian Army.

Frederick II (later called "The Great") recognised the value of hussars as light cavalry and encouraged their recruitment. In 1741 he established a further five regiments, largely from Polish deserters. Three more regiments were raised for Prussian service in 1744 and another in 1758. While the hussars were increasingly drawn from Prussian and other German cavalrymen, they continued to wear the traditional Hungarian uniform, richly decorated with braid and gold trim.

Possibly due to a daring and impudent surprise raid on his capital Berlin by the hussars of Hungarian general András Hadik, Frederick also recognised the national characteristics of his Hungarian recruits and in 1759 issued a royal order which warned the Prussian officers never to offend the self-esteem of his hussars with insults and abuses. At the same time he exempted the hussars from the usual disciplinary measures of the Prussian Army: physical punishments including cudgeling.

Frederick used his hussars for reconnaissance duties and for surprise attacks against the enemy's flanks and rear. A hussar regiment under the command of Colonel Sigismund Dabasi-Halász won the Battle of Hohenfriedberg at Striegau on May 4, 1745, by attacking the Austrian combat formation on its flank and capturing its entire artillery.

The effectiveness of the hussars in Frederick's army can be judged by the number of promotions and decorations awarded to their officers. Recipients included the Hungarian generals Pal Werner and Ferenc Kőszeghy, who received the highest Prussian military order, the "Pour le Merite"; General Tivadar Ruesh was awarded the title of baron; Mihály Székely was promoted from the rank of captain to general after less than fifteen years of service.

While Hungarian hussars served in the opposing armies of Frederick and Maria Theresa there were no known instances of fratricidal clashes between them.

Hussar Verbounko

Verbunkos (Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈvɛɾbunkoʃ], other spellings are Verbounko, Verbunko, Verbunkas, Werbunkos, Werbunkosch, Verbunkoche) is an 18th-century Hungarian dance and music genre.

The name is derived from the German word werben that means, in particular, "to enroll in the army"; verbunkos—recruiter. The corresponding music and dance was played during military recruiting, which was a frequent event during this period, hence the character of the music. The verbunkos was an important component of the Hungarian hussar tradition. Potential recruits were dressed in items of hussar uniform, given wine to drink and invited to dance to this music.[12]

Heavy hussars of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Initially the first units of Polish hussars in the Kingdom of Poland were formed in 1500, which consisted of Serbian[13] mercenaries. Quickly recruitment also began among Polish and Lithuanian citizens. Being far more manoeuvrable than the heavily armoured lancers previously employed, the hussars proved vital to the Polish and Lithuanian victories at Orsza (1514) and Obertyn (1531).

Over the course of the 1500s hussars in Hungary had become heavier in character: they had abandoned wooden shields and adopted plate metal body armour. When Stefan Bathory, a Transylvanian-Hungarian prince, was elected king of Poland in 1576 he reorganised the Polish-Lithuanian hussars of his Royal Guard along Hungarian lines, making them a heavy formation, equipped with a long lance as their main weapon. By the reign of King Stefan Batory the hussars had replaced medieval-style lancers in the Polish-Lithuanian army, and they now formed the bulk of the Polish cavalry. By the 1590s most Polish-Lithuanian hussar units had been reformed along the same 'heavy' Hungarian model. These Polish 'heavy' hussars were known in their homeland as husaria.

With the Battle of Lubieszów in 1577 the 'Golden Age' of the husaria began. Down to and including the Battle of Vienna in 1683, the Polish-Lithuanian hussars fought countless actions against a variety of enemies. In the battles of Byczyna (1588), Kokenhusen (1601), Kircholm (1605), Kłuszyn (1610), Trzciana (1629), Chocim (1673) and Lwów (1675), the Polish-Lithuanian hussars proved to be the decisive factor often against overwhelming odds.

Until the 18th century they were considered the elite of the Commonwealth armed forces.

Hussars in the 18th century

Hussars outside the Polish Kingdom followed a different line of development. During the early decades of the 17th century hussars in Hungary ceased to wear metal body armour; and by 1640 most were now light cavalry. It was hussars of this 'light' pattern rather than the Polish heavy hussar that were later to be copied across Europe. These light hussars were ideal for reconnaissance and raiding sources of fodder and provisions in advance of the army. In battle, they were used in such light cavalry roles as harassing enemy skirmishers, overrunning artillery positions, and pursuing fleeing troops.

In the late 17th and 18th centuries many Hungarian hussars fled to other Central and Western European countries and became the core of similar light cavalry formations created there. Following their example, hussar regiments were introduced into many of the armies of Europe.

Bavaria raised its first hussar regiment in 1688 and a second one about 1700. Prussia followed suit in 1721 when Frederick the Great used hussar units extensively during the War of the Austrian Succession.[1]

France established a number of hussar regiments from 1692 on, recruiting originally from Hungary and Germany, then subsequently from German speaking frontier regions within France itself. The first Hussar regiment in France was founded by a Hungarian lieutenant named Ladislas Ignace de Bercheny.[2]

Russia relied on its native cossacks to provide irregular light horse until 1741. Recruited largely from Christian Orthodox communities along the Turkish frontier, the newly raised Russian hussar units increased to 12 regiments by the Seven Years War. Founder of the first Russian Hussar regiment was Ádám Mányoki also a Hungarian officer.

Spain disbanded its first hussars in 1747 and then raised new units, the Españoles Hussar Regiment in 1795. Húsares de Pavía was created in 1684 by the Count of Melgar to serve in Spanish possessions in Italy and was named after the Spanish victory over the French army in, at Pavia, Italy, south of Milan. During the battle, the King of France, Francisco I,was captured by the Spanish Cavalry. The Húsares de Pavía fought in Italy during the War of Piamonte (1692–1695)and When the Spanish Succession War ended, it was transferred back to Spain. In 1719, the regiment was sent again to Italy until 1746. Then, it served in campaigns against Algerian pirates and sieges of Oran and Algiers. During the Spanish War Independence against Napoleon (1808–1814), the unit fought the Battles of Bailén, Tudela, Velez, Talavera and Ocaña and the actions of Baza, Cuellar, Murviedro and Alacuas. The Húsares de Pavía regiment also was involved in the Ten Years' War in Cuban, the Spanish-American War(1898), Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), and in the Campaign of Ifni (1958). Ifni was a Spanish colony in North Africa that was attacked by irregulars from Morocco. At present, this regiment is named Regimiento Acorazado de Caballeria Pavia nr 4 (Cavalry armored regiment Pavia nr 4) garrisoned in Zaragoza (Spain).

Sweden had hussars from about 1756 and Denmark introduced this class of cavalry in 1762.

Great Britain hired German hussars among their Hessian mercenaries and sent them to America to fight in the American War of Independence. Britain converted a number of light dragoon regiments to hussars in the early nineteenth century.

The United Provinces raised its first Hussar regiment in 1784, and a second in 1787. During the French occupation from 1795–1813, there were a maximum of two hussar regiments. After regaining independence, the new Royal Netherlands Army raised two hussar regiments (nrs. 6 and 8). They were disbanded (nr. 8 in 1830), or changed into Lancers (nr. 6 in 1841). In 1867, all remaining cavalry regiments were transferred to hussar regiments. This tradition remains until this day.

Hussars in Russia

In 1707 Apostol Kigetsch, a Wallachian nobleman under Peter the Great, was given the task to form a 'khorugv' ("banner" or "squadron") of 300 men that would be employed on the Turkish-Russian border. The squadron consisted of Christians from Hungary, Serbia, Moldova and Wallachia.[14]

In 1711 prior to the Pruth campaign, 6 regiments (4 khorugv's each) of hussars were formed, mainly from Wallachia. Two other 'khorugv' for guerilla warfare were formed, one Polish and one Serbian, that would tackle the Turks.

In 1723, Peter the Great formed a Hussar regiment exclusively from Serbian light cavalry serving in the Austrian army.[14]

On October 14, 1741 Princess Anna Leopoldovna of Braunschweig-Lunenburg, who ruled Russia from November 11, 1740 to November 25, 1741, authorised the raising of 4 Hussar regiments from natives who had remained in Russia:

- Serbskiy (Serbian)

- Moldavskiy (Moldavian)

- Vengerskiy (Hungarian)

- Gruzinskiy (Georgian)

They were raised from above-mentioned various Hussar companies, converted to regular service after the War 1736-39. This regiments were enlisted, not conscripted as the rest of Russian army, and were on a level between regular and irregular cavalry. Hussars were recruited only from the title nation, i.e. this regiments were national units on Russian service: all troops (incl. officers) were national and commands were given in the national languages. Each regiment was supposed to have a fixed organization of 10 companies, each of about 100 men, but these regiments were recruited from different sources, so they were less than authorised strength.

Later in 1759-60, three more Hussar regiments were raised:

- Zeltiy (Yellow)

- Makedonskiy (Macedonian)

- Bolgarskiy (Bulgarian)

Hussars of the Napoleonic Wars

.jpg)

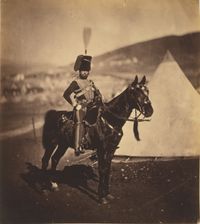

The hussars played a prominent role as cavalry in the Napoleonic Wars (1796–1815). As light cavalrymen mounted on fast horses, they would be used to fight skirmish battles and for scouting. Most of the great European powers raised hussar regiments. The armies of France, Austria, Prussia, and Russia had included hussar regiments since the mid-18th century. In the case of Britain four light dragoon regiments were converted to hussars in 1805. Hussars were notoriously impetuous, and Napoleon was quoted as stating that he would be surprised for a hussar to live beyond the age of thirty due to their tendency to become reckless in battle, exposing their weaknesses in frontal assaults. The hussars of Napoleon created the tradition of sabrage, the opening of a champagne bottle with a sabre.

The uniform of the Napoleonic hussars included the pelisse: a short fur edged jacket which was often worn slung over one shoulder in the style of a cape, and was fastened with a cord. This garment was extensively adorned with braiding (often gold or silver for officers) and several rows of multiple buttons. Under it was worn the dolman or tunic which was also decorated in braid. On active service the hussar normally wore reinforced breeches which had leather on the inside of the leg to prevent them from wearing due to the extensive riding in the saddle. On the outside of such breeches, running up the outside was a row of buttons, and sometimes a stripe in a different colour. In terms of headwear the hussar wore either a shako or fur busby. The colours of dolman, pelisse and breeches varied greatly by regiment, even within the same army. The French hussar of the Napoleonic period was armed with a brass hilted sabre and sometimes with a brace of pistols although these were often unavailable.

A famous military commander in Bonaparte's army who began his military career as a hussar was Marshal Ney, who after being employed as a clerk in an iron works joined the 5th Hussars in 1787. He rose through the ranks of the hussars in the wars of Belgium and the Rhineland (1794–1798) fighting against the forces of Austria and Prussia before receiving his marshal's baton in 1804 after the Emperor Napoleon's coronation.

19th century

Eastern Europe

Although the Romanian cavalry were not formally designated as hussars, their pre-1915 uniforms as described below were of the classic hussar type. These regiments were created in the second part of the 19th century under the rule of Alexandru Ioan Cuza, creator of Romania by the unification of Moldova and Wallachia. Romania diplomatically avoided the word "hussar" due to its connotation at the time with Austro-Hungary, traditional sovereign or rival of the Romanian principates. Therefore these cavalry regiments were called "Călăraşi" in Moldavia, and later the designation "Roşiori" was adopted in Wallachia. (The word "călăraş" means "mounted soldier", and "roşior" means "of red colour" which derived from the colour of their uniform.) The three (later expanded to ten) Roşiori regiments were the regular units, while the Călăraşi were territorial reserve cavalry who supplied their own horses. These troops played an important role in the Romanian Independence War of 1877 on the Russo-Turkish front. The Roşiori, as their name implies in Romanian, wore red dolmans with black braiding while the Călăraşi wore dark blue dolmans with red loopings. Both wore fur busbies and white plumes. The Roşiori regiments were distinguished by the different colours of their cloth busby bags (yellow, white, green, light blue, light green, dark blue, light brown, lilac, pink and light grey according to regiment). The Regimentul 1 Roşiori "General de armată Alexandru Averescu" was formed in 1871, while the Regimentul 4 Roşiori "Regina Maria" was created in 1893. After World War I the differences between the two branches of Romanian cavalry disappeared, although the titles of Roşiori and Călăraşi remained. Both types of cavalry served through World War II on the Russian front as mounted and mechanised units.

Latin America

In Argentina, the 'Regimiento de Húsares del Rey' was created in 1806 to defend Buenos Aires from the British 1806-1807 expeditions. After the Revolution in 1810, it became the 'Regimiento Húsares de Pueyrredón' after its founder and first colonel, Juan Martín de Pueyrredón.

In Chile, the 'Húsares de la Muerte', or 'Death Hussars', were created as a paramilitary corps by Manuel Rodríguez after the 'Desastre de Cancha Rayada' (Disaster of Cancha Rayada) that took place the 26 of March 1818, during the period known as the Patria Vieja (Old Fatherland).

In Peru, the squadrons of Hussars of the Peruvian Legion of the Guard were created in 1821 by General Jose de San Martin, from officers and troopers of the Squadron of "Hussars of the General's Escort", the former Squadron of Horse-Chasseurs of the Andes, which were included in the newly created army of the then recently independent republic of Peru. The 4th Squadron of the Hussars of the Peruvian Legion of the Guard was organised in Trujillo under the command of Peruvian Colonel Antonio Gutiérrez de la Fuente, and was named after "Cuirassiers" in 1823 and became into "Hussars of Perú" Squadron in 1824.

It was renamed "Hussars of Junín" for its performance in 1824 at the Battle of Junin, which was one of the Spanish-Peruvian battles which determined the final defeat of the Spanish colonial rule. The Hussars of Junín fought at the battle of Ayacucho on 9 December 1824, among the liberating forces commanded by Antonio de Sucre against the loyalist Spanish forces commanded by Viceroy José de la Serna. The heroic action of the "Hussars of Junín" Regiment as part of the Light Horse commanded by General José María Córdoba were victorious, the battle eventuating in the capitulation of the Spanish forces, affirming the final independence of Peru. For this heroic action the "Hussars of Junín" Regiment of the Light Horse was titled after Liberator of Perú with inscription on the regimental guidon.

Hussars in the early 20th century

On the eve of World War I there were still hussar regiments in the British (including Canadian), French, Spanish, German, Russian, Dutch, Danish, Swedish, Romanian and Austro-Hungarian armies. In most respects they had now become regular light cavalry, recruited solely from their own countries and trained and equipped along the same lines as other classes of cavalry. Hussars were however still notable for their colourful and elaborate parade uniforms, the most spectacular of which were those worn by the two Spanish regiments, Husares de Pavia and Husares de la Princesa. A characteristic of both the Imperial German and Russian Hussars was the variety of colours apparent in their dress uniforms. These included red, black, green, dark and light blue, brown and even pink (the Russian 15th Hussars) dolmans. Most Russian hussar regiments wore red breeches as did all the Austro-Hungarian hussars of 1914. This rainbow effect harked back to the 18th century origins of hussar regiments in these armies and helped regrouping after battle or a charge. The fourteen French hussar regiments were an exception to this rule - they wore the same relatively simple uniform, with only minor distinctions, as the other branches of French light cavalry. This comprised a shako, light blue tunic and red breeches. The twelve British hussar regiments were distinguished by different coloured busby bags and a few other distinctions such as the yellow plumes of the 20th, the buff collars of the 13th and the crimson breeches of the 11th Hussars.

Hussar influences were apparent even in those armies which did not formally include hussar regiments. Thus both the Belgium Guides (prior to World War I) and the Mounted Escort, the so-called Blue Hussars, of the Irish Defence Forces (during the 1930s) wore hussar style uniforms.

Armoured units

After horse cavalry became obsolete, hussar units were generally converted to armoured units, though retaining their traditional titles. Hussar regiments still exist today, in the British Army (although amalgamations have reduced their number to two only), the French Army, the Swedish Army (Livregementets husarer, the Life Regiment Hussars), the Dutch Army and the Canadian Forces, usually as tank forces or light mechanised infantry. The Danish Guard Hussars provide a ceremonial mounted squadron, which is the last to wear the slung pelisse.

The Hussar image

The colourful military uniforms of hussars from 1700 onwards were inspired by the prevailing Hungarian fashions of the day. Usually this uniform consisted of a short jacket known as a dolman, or later a medium-length "attila" jacket, both with heavy horizontal gold braid on the breast, and yellow braided or gold Austrian knots (sújtás) on the sleeves; a matching pelisse (a short-waisted overjacket often worn slung over one shoulder); coloured trousers, sometimes with yellow braided or gold Austrian knots at the front; a busby (kucsma) (a high fur hat with a cloth bag hanging from one side; although some regiments wore the shako (csákó) of various styles); and high riding boots.

European (but not British) hussars traditionally wore long moustaches (but no beards) and long hair, with two plaits hanging in front of the ears as well as a larger queue at the back. They often retained the queue, which used to be common to all soldiers, after other regiments had dispensed with it and adopted short hair.

Hussars had a reputation for being the dashing, if unruly, adventurers of the army. The traditional image of the hussar is of a reckless, hard-drinking, hard-swearing, womanising, moustachioed, swashbuckler. General Lasalle, an archetypal showoff hussar officer, epitomized this attitude by his remarks, among which the most famous is : "Any hussar who is not dead by the age of thirty is a blackguard." He died at the Battle of Wagram at the age of 34.

Arthur Conan Doyle's character Brigadier Etienne Gerard of the French Hussards de Conflans has come to epitomise the hussar of popular fiction — brave, conceited, amorous, a skilled horseman and (according to Napoleon) not very intelligent. Brigadier Gerard's boast that the Hussards de Conflans (an actual regiment) could set a whole population running, the men away from them and the women towards them, may be taken as a fair representation of the esprit de corps of this class of cavalry.

Less romantically, 18th century hussars were also known (and feared) for their poor treatment of local civilians. In addition to commandeering local food-stocks for the army, hussars were known to also use the opportunity for personal looting and pillaging.

Armament and tactics

Hussar armament varied over time. Until the 1600s it included a cavalry sabre, lance, long wooden shield and, optionally, light metal armour or simple leather vest. Their usual form of attack was to make a rapid charge in compact formation against enemy infantry or cavalry units. If the first attack failed, they would retire to their supporting troops who re-equipped them with fresh lances, and then would charge again.

Apart from the Polish sabre and the lance, Polish heavy hussars were usually also equipped with two pistols, a small rounded shield and koncerz, a long (up to 2 metres) stabbing sword used in charge when the lance was broken, and some with horseman's pick. Also the armour became heavier and with time it was replaced by shield armour.

Unlike their lighter counterparts, the Polish hussars were used as a heavy cavalry for line-breaking charges against enemy infantry. The famous low losses were achieved by the unique tactic of late concentration. Until the first musket salvo of the enemy infantry, the hussars were approaching relatively slowly, in a loose formation. Each rider was at least 5 steps away from his colleagues and the infantry using still undeveloped muskets simply could not aim at any particular cavalryman. Also, if a hussar's horse was wounded, the following lines had time to steer clear of him. After the salvo, the cavalry rapidly accelerated and joined up the ranks. At the moment of the clash of the charging cavalry with the defenders, the hussars were riding knee-to-knee.

Hussars of the Polish Commonwealth were also famous for the huge 'wings' worn on their backs or attached to the saddles of their horses. There are several theories which try to explain the meaning of the wings. According to some they were designed to foil attacks by Tatar lasso; another theory has it that the sound of vibrating feathers attached to the wings made a strange sound that frightened enemy horses during the charge. However, recent experiments carried over by Polish historians in 2001 did not support any of these theories and the phenomenon remains unexplained. Most probably the wings were worn only during parades and not during combat, but this explanation is also disputed.

The Hussars of Central and Western Europe in the 18th and 19th century were typically armed with a curved sabre, one or two pistols carried in holsters at the front of the saddle and a carbine.

Current hussar units

Argentina

The 'Regimiento Húsares de Pueyrredón' currently serves as an armoured regiment (the 'RCT No 10 Húsares de Pueyrredón') using its Revolutionary era uniforms in full regalia during formal parades.

Canada

-

- Note: All Canadian hussar regiments are reserve force armoured reconnaissance units.

- 1st Hussars

- 8th Canadian Hussars (Princess Louise's)

- The Royal Canadian Hussars (Montreal)

- Sherbrooke Hussars

Denmark

- Gardehusarregimentet (English: Guard Hussar Regiment). Founded in 1762. Currently it is a mixed armour/infantry unit with seven battalions. In addition to its operational role, the Guard Hussar Regiment is one of two regiments in the Danish Army (along with the Den Kongelige Livgarde) to be classed as 'Guards'; in this case, the Guard Hussars perform the same role as the Household Cavalry do in the British Army. In mounted parade uniform the Gardehusarregimentet are the only hussars to still wear the slung and braided pelisse which was formerly characteristic of this class of cavalry.

France

- 1st Airborne Hussars Regiment (or 1st Hussar Parachute battalion) : 1er Régiment de Hussards Parachutistes (1er RHP). Founded in 1720, currently stationed in Tarbes, Hautes-Pyrénées, France. Formerly the "Hussards de Bercheny", after the founder, Count Bercheny, who was a Hungarian noble. French official website : 1rhp.info

- 2ème régiment de Hussards (2e RH) (2nd Hussar Regiment). Founded in 1735, currently stationed in Sourdun, Provins arrondissement. Traditionally called "Chamborant".

- 3ème régiment de Hussards (3e RH) (3rd Hussar Regiment). Founded in 1764, currently stationed in Immendingen, Tuttlingen district, Germany. Part of the Franco-German Brigade. Formerly the "Hussards d'Esterhazy".

- 4ème régiment de Hussards (4e RH) (4th Hussar Regiment). Founded in 1791, currently stationed in Metz.

It should be noted that because of political upheavals, such as the French Revolution and the Restoration of 1815, the French Hussar regiments do not have the same historical continuity as their counterparts in some others armies.

Hussard noir (black hussar) was the nickname of primary teachers in the Third Republic because of their black coat.

Netherlands

The Dutch word for hussar is huzaar ([hʊˈzaːʁ]).

- Regiment Huzaren Van Sytzama, eldest element founded in 1577

- Regiment Huzaren Prins van Oranje, eldest element founded in 1668

- Regiment Huzaren Prins Alexander (disbanded 2007), eldest element founded in 1672

- Regiment Huzaren van Boreel, eldest element founded in 1585

Except for the Huzaren Van Boreel, every regiment operates in the armoured role in one of the two mechanised brigades of the Dutch army, using the Leopard 2 main battle tank. Each of these brigades also has a squadron from the Huzaren Van Boreel attached for reconnaissance. There is also a mounted unit for ceremonies: Cavalerie Ere-Escorte. It is linked to the Huzaren Prins Alexander although riders from other regiments participate as well.

Peru

The 1st Cavalry, "Glorious Hussars of Junín Liberator of Perú" Regiment forms a personal mounted guard to the Peruvian President Alan García Pérez since 1987[15] and wear a stylised uniform of a red coat and blue breeches, that are supposed to have been worn in 1824. The hussars carry lances on parade, and mount a dismounted guard in the Government Palace of Perú.

Spain

Húsar de Pavía: Regimiento Acorazado de Caballeria Pavia nr 4 (Cavalry armored regiment Pavia nr 4) garrisoned in Zaragoza (Spain).

Sweden

- Livregementets husarer (English: Life Regiment Hussars). Founded in 1667 when the Uplandian Cavalry were made into a royal guards regiment. Today Livregementets husarer, also known as K 3, is the last remaining hussar regiment in Sweden and trains one of the two special service units of the Swedish army: the parachute rangers.

United Kingdom

- The Queen's Royal Hussars (The Queen's Own and Royal Irish)

- The King's Royal Hussars

- 60 (Royal Buckinghamshire Hussars) Signal Squadron

- Leicestershire Yeomanry (P.A.O)

Presently, the first two regiments operate in the Armoured role, primarily operating the Challenger 2 main battle tank. The Hussar regiments are grouped together with the Dragoon and Lancer regiments in the order of precedence, all of which are below the Dragoon Guards.

Although a Dragoon regiment, The Light Dragoons was formed by the amalgamation of two Hussar regiments, the 13th/18th Royal Hussars (Queen Mary's Own) and the 15th/19th The King's Royal Hussars, in 1992. This marks a reversal of the trend during the mid-19th century when all light dragoon regiments then existing were converted to hussars.

60 (Royal Buckinghamshire Hussars) Signal Squadron is a Territorial Army unit within 36 (Eastern) Signal Regiment and was formed in 1999 from the 5th Battalion The Royal Green Jackets.

See also

References and notes

- ↑ Cowley, Robert; Geoffrey Parker (2001). The Reader's Companion to Military History. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 215. ISBN 9780618127429.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Corvisier, André; John Childs, translated by Chris Turner (1994). A dictionary of military history and the art of war (2 ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 367. ISBN 9780631168485.

- ↑ Austro-Hungarian Army of the Seven Years War AvAlbert Seaton

- ↑ Philip Babcock Gove, ed (1986). "Hussar". Webster's Third New International Dictionary. 2. Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster. pp. Page 1105. ISBN 0-85229-503-0.

- ↑ George T. Denis, Three Byzantine Military Treatises (Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 1985) p. 153.

- ↑ Polish Winged Hussar 1576-1775 - Richard Brzezinski,Velimir Vukšić

- ↑ M. Canard, "Sur Deux Termes Militaires Byzantins d'Origin Orientale" in Byzantion, 40 (1970), pp. 226-29.

- ↑ Haythornthwaite, Philip J.; Bryan Fosten (1986). "Hussars". Austrian army of the Napoleonic Wars. Osprey Publishing. pp. 22. ISBN 9780850457261.

- ↑ Haywood, Matthew (February 2002). Hussars (Gusars). Wargaming and Warfare in Eastern Europe. http://www.warfareeast.co.uk/main/Hungarian_Composition.htm. Retrieved 2008-10-09. "In Matthius' reign the Hussars were equally referred to in the sources as Rac [an old Hungarian name for Serbs]. The primary reason for this being that the majority of Hussars were supplied by Serbian exiles or mercenaries."

- ↑ Nicolle, David; Witold Sarnecki (February 2008). Medieval Polish Armies 966-1500. Men-at-Arms. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. pp. 19. ISBN 9781846030147. http://books.google.com/books?id=i3wRJpR8LOQC&pg=PA19&sig=ACfU3U3pZP3kc6tMFpQqdYiQ393_dYDa7A. "One of several likely models for this development were those light hussars of Serbian origin who had first appeared in the Hungarian army of king Matthias Corvinus (the Serbian word гусар meaning bandit or robber)."

- ↑ Haywood, Matthew (February 2002). "Hussars (Gusars)". Hungarian Army Composition. Wargaming and Warfare in Eastern Europe. http://www.warfareeast.co.uk/main/Hungarian_Composition.htm. Retrieved 2008-10-09. "In Matthius' reign the Hussars were equally referred to in the sources as Rac [an old Hungarian name for Serbs]. The primary reason for this being that the majority of Hussars were supplied by Serbian exiles or mercenaries."

- ↑ Video: Verbounko music and Hussars

- ↑ Brzezinski, Richard and Velimir Vukšić, Polish Winged Hussar 1576-1775, (Osprey Publishing Ltd., 2006), 6.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Peter the Great's army, Volym 2-Angus Konstam

- ↑ In february, 1987 Alan García ordered 1st Cavalry, "Glorious Hussars of Junín" Regiment, Perú's Liberator, to be his life-guard

Further reading

- Radosław Sikora, Fenomen husarii

- Bronisław Gembarzewski, Husarze. Ubiór, oporządzenie i uzbrojenie 1500–1775

- Zbigniew Bocheński, Ze studiów nad polską zbroją husarską in: Rozprawy i sprawozdania Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie. Kraków, 1960

- Marek Plewczyński, Obertyn 1531

- Romuald Romański, Beresteczko 1651

- Leszek Podhorodecki, Sławne bitwy Polaków

- Szymon Kobyliński, Szymona Kobylińskiego gawędy o broni i mundurze

- Janusz Sikorski, Zarys dziejów wojskowości polskiej do roku 1864

- Jan Chryzostom Pasek, Pamiętniki

- Mirosław Nagielski, Relacje wojenne z pierwszych lat walk polsko-kozackich powstania Bohdana Chmielnickiego

- Bitwa pod Gniewem 22.IX – 29.IX. 1626, pierwsza porażka husarii in: Studia i materiały do historii wojskowości, Warsaw, 1966

- J. Cichowski, A. Szulczyński, Husaria

- Jakub Łoś, Pamiętnik towarzysza chorągwi pancernej

- Brzezinski, Richard. Polish Armies 1569-1600. (volume 1) #184 in the Osprey Men-at-Arms Series. London: Osprey Publishing, 6, 16.

- Brzezinski, Richard. Polish Winged Hussar 1576-1775. Warrior Series. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd., 2006.

- Hollins, David. Hungarian Hussars 1756-1815. Osprey Warrior Series. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, Ltd., 2003.

- Klucina, Petr. (Illustrations by Pavol Pevny), Armor: From Ancient To Modern Times. Reprinted by New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1992, (by permission of Slovart Publishing Ltd, Batislava).

- Ostrowski, Jan K., et al., Art in Poland: Land of the Winged Horsemen 1572-1764. Baltimore: Art Services International, 1999.

- Wasilkowska, Anna. The Winged Horsemen. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Interpress, 1998.

- Zamoyski, Adam. The Polish Way. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1996.

External links

- Hussars Photographs

- video of a Hussar colour party canter

- First American Living History group to portray the Polish winged Hussars

- 1st re-enacment group in the U.S.A. to represent the winged hussars

- The famous Hungarian hussar

- French official website of the Bercheny's - 1st Airborne Hussars Regiment

- Hungarian Hussar site.

- About Polish Hussars on Polish Renaissance Warfare site

- How the Polish Hussars Fought

- Polish Hussars Feature on MyArmoury.com

- [3]