Homeschooling

Homeschooling or homeschool (also called home education or home learning) is the education of children at home, typically by parents but sometimes by tutors, rather than in other formal settings of public or private school. Although prior to the introduction of compulsory school attendance laws, most childhood education occurred within the family or community,[1] homeschooling in the modern sense is an alternative in developed countries to educational institutions operated by civil governments.

Homeschooling is a legal option in many places for parents to provide their children with a learning environment as an alternative to publicly-provided schools. Parents cite numerous reasons as motivations to homeschool, including better academic test results, poor public school environment, improved character/morality development, and objections to what is taught locally in public school. It may be a factor in the choice of parenting style. It is also an alternative for families living in isolated rural locations or living temporarily abroad.

Homeschooling may also refer to instruction in the home under the supervision of correspondence schools or umbrella schools. In some places, an approved curriculum is legally required if children are to be home-schooled.[2] A curriculum-free philosophy of homeschooling may be called unschooling, a term coined in 1977 by American educator and author John Holt in his magazine Growing Without Schooling.

History

For much of history and in many cultures, enlisting professional teachers (whether as tutors or in a formal academic setting) was an option available only to a small elite. Thus, until relatively recently, the vast majority of people were educated by parents (especially during early childhood)[1] and in the fields or learning a trade.

The earliest compulsory education in the West began in the late 17th century and early 18th century in the German states of Gotha, Calemberg and, particularly, Prussia.[3] However, even in the 18th century, the vast majority of people in Europe lacked formal schooling, which means they were homeschooled or received no education at all.[4] The same was also true for colonial America[5] and for the United States until the 1850s.[6] Formal schooling in a classroom setting has been the most common means of schooling throughout the world, especially in developed countries, since the early and mid 19th century. Native Americans, who traditionally used homeschooling and apprenticeship, strenuously resisted compulsory education in the United States.[7]

In 1964, John Caldwell Holt, published a book entitled How Children Fail which criticized traditional schools of the time. The book was based on a theory he had developed as a teacher – that the academic failure of schoolchildren was caused by pressure placed on children by adults. Holt began making appearances on major TV talk shows and writing book reviews for Life magazine.[8] In his follow-up work, How Children Learn, 1967, he tried to demonstrate the learning process of children and why he believed school short-circuits this process.

In these books, Holt had not suggested any alternative to institutional schooling; he had hoped to initiate a profound rethinking of education to make schools friendlier toward children. As the years passed he became convinced that the way schools were was what society wanted, and that a serious re-examination was not going to happen in his lifetime.

During this time, the American educational professionals Raymond and Dorothy Moore began to research the academic validity of the rapidly growing Early Childhood Education movement. This research included independent studies by other researchers and a review of over 8,000 studies bearing on Early Childhood Education and the physical and mental development of children.

They asserted that formal schooling before ages 8–12 not only lacked the anticipated effectiveness, but was actually harmful to children. The Moores began to publish their view that formal schooling was damaging young children academically, socially, mentally, and even physiologically. They presented evidence that childhood problems such as juvenile delinquency, nearsightedness, increased enrollment of students in special education classes, and behavioral problems were the result of increasingly earlier enrollment of students.[9] The Moores cited studies demonstrating that orphans who were given surrogate mothers were measurably more intelligent, with superior long term effects – even though the mothers were mentally retarded teenagers – and that illiterate tribal mothers in Africa produced children who were socially and emotionally more advanced than typical western children, by western standards of measurement.[9]

Their primary assertion was that the bonds and emotional development made at home with parents during these years produced critical long term results that were cut short by enrollment in schools, and could neither be replaced nor afterward corrected in an institutional setting.[9] Recognizing a necessity for early out-of-home care for some children – particularly special needs and starkly impoverished children, and children from exceptionally inferior homes– they maintained that the vast majority of children are far better situated at home, even with mediocre parents, than with the most gifted and motivated teachers in a school setting (assuming that the child has a gifted and motivated teacher). They described the difference as follows: "This is like saying, if you can help a child by taking him off the cold street and housing him in a warm tent, then warm tents should be provided for all children – when obviously most children already have even more secure housing."[10]

Similar to Holt, the Moores embraced homeschooling after the publication of their first work, Better Late Than Early, 1975, and went on to become important homeschool advocates and consultants with the publication of books like Home Grown Kids, 1981, Homeschool Burnout, and others.[9]

At the time, other authors published books questioning the premises and efficacy of compulsory schooling, including Deschooling Society by Ivan Illich, 1970 and No More Public School by Harold Bennet, 1972.

In 1976, Holt published Instead of Education; Ways to Help People Do Things Better. In its conclusion he called for a "Children's Underground Railroad" to help children escape compulsory schooling.[8] In response, Holt was contacted by families from around the U.S. to tell him that they were educating their children at home. In 1977, after corresponding with a number of these families, Holt began producing a magazine dedicated to home education: Growing Without Schooling.[11]

In 1980, Holt said, "I want to make it clear that I don't see homeschooling as some kind of answer to badness of schools. I think that the home is the proper base for the exploration of the world which we call learning or education. Home would be the best base no matter how good the schools were."[12]

Holt later wrote a book about homeschooling, Teach Your Own, in 1981.

One common theme in the homeschool philosophies of both Holt and the Moores is that home education should not be an attempt to bring the school construct into the home, or a view of education as an academic preliminary to life. They viewed it as a natural, experiential aspect of life that occurs as the members of the family are involved with one another in daily living.

Methodology

Homeschools use a wide variety of methods and materials. There are different paradigms, or educational philosophies, that families adopt including unit studies, Classical education (including Trivium, Quadrivium), Charlotte Mason education, Montessori method, Theory of multiple intelligences, Unschooling, Radical Unschooling, Waldorf education, School-at-home, A Thomas Jefferson Education, and many others. Some of these approaches, particularly unit studies, Montessori, and Waldorf, are also available in private or public school settings.

It is not uncommon for the student to experience more than one approach as the family discovers what works best for them. Many families do choose an eclectic (mixed) approach. For sources of curricula and books, "Homeschooling in the United States: 2003"[13] found that 78 percent utilized "a public library"; 77 percent used "a homeschooling catalog, publisher, or individual specialist"; 68 percent used "retail bookstore or other store"; 60 percent used "an education publisher that was not affiliated with homeschooling." "Approximately half" used curriculum or books from "a homeschooling organization", 37 percent from a "church, synagogue or other religious institution" and 23 percent from "their local public school or district." 41 percent in 2003 utilized some sort of distance learning, approximately 20 percent by "television, video or radio"; 19 percent via "Internet, e-mail, or the World Wide Web"; and 15 percent taking a "correspondence course by mail designed specifically for homeschoolers."

Individual governmental units, e, g, states and local districts, vary in official curriculum and attendance requirements.[14]

Unit studies

The unit study approach incorporates several subjects, such as art, history, math, science, geography and other curriculum subjects, around the context of one topical theme, like water, animals, American slavery, or ancient Rome.[15] For example, a unit study of Native Americans could combine age-appropriate lessons in: social studies, how different tribes lived prior to colonization vs. today; art, making Native American clothing; history (of Native Americans in the U.S.); reading from a special reading list; and the science of plants used by Native Americans.

Unit studies are particularly helpful for teaching multiple grade levels simultaneously, as the topic can easily be adjusted (i.e. from an 8th grader detailing and labeling a spider's anatomy to an elementary student drawing a picture of a spider on its web). As it is generally the case that in a given "homeschool" very few students are spread out among the grade levels, the unit study approach is an attractive option.

Unit study advocates assert that children retain 45% more information following this approach.[15]

All-in-one curricula

"All-in-one" curricula, sometimes called a "school in a box", are comprehensive packages covering many subjects; usually an entire year's worth. They contain all needed books and materials, including pencils and writing paper. Most such curricula were developed for isolated families who lack access to public schools, libraries and shops .

Typically, these materials recreate the school environment in the home and are based on the same subject-area expectations as publicly run schools, allowing an easy transition into school. They are among the more expensive options, but are easy to use and require minimal preparation. The guides are usually extensive, with step-by-step instructions. These programs may include standardized tests and remote examinations to yield an accredited school diploma.

Student-paced learning

Similar to All-in-one curricula are learner-paced curriculum packages. These workbooks allow the student to progress at their own speed.

Online education

Online resources for homeschooling include courses of study, curricula, educational games, online tests, online tutoring, and occupational training. Online learning potentially allows students and families access to specialized teachers and materials and greater flexibility in scheduling. Parents can be with their children during online tutoring session. Finally, online tutoring is useful for students who are disabled or otherwise limited in their ability to travel.

Community resources

Homeschoolers often take advantage of educational opportunities at museums, community centers, athletic clubs, after-school programs, churches, science preserves, parks, and other community resources. Secondary school level students may take classes at community colleges, which typically have open admission policies. In many communities, homeschooling parents and students participate in community theater, dance, band, symphony, and chorale opportunities.

Groups of homeschooling families often join together to create homeschool co-ops. These groups typically meet once a week and provide a classroom environment. These are family-centered support groups whose members seek to pool their talents and resources in a collective effort to broaden the scope of their children's education. They provide a classroom environment where students can do hands-on and group learning such as performing, science experiments, art projects, foreign language study, spelling bees, discussions, etc. Parents whose children take classes serve in volunteer roles to keep costs low and make the program a success.

Certain states, such as Maine and New Mexico, have laws that permit homeschooling families to take advantage of public school resources. In such cases, children can be members of sports teams, be members of the school band, can take art classes, and utilize services such as speech therapy while maintaining their homeschool lifestyle.

Unschooling and natural learning

Some people use the terms "unschooling" or "radical unschooling" to describe all methods of education that are not based in a school.

"Natural learning" refers to a type of learning-on-demand where children pursue knowledge based on their interests and parents take an active part in facilitating activities and experiences conducive to learning but do not rely heavily on textbooks or spend much time "teaching", looking instead for "learning moments" throughout their daily activities. Parents see their role as that of affirming through positive feedback and modeling the necessary skills, and the child's role as being responsible for asking and learning.

The term "unschooling" as coined by John Holt describes an approach in which parents do not authoritatively direct the child's education, but interact with the child following the child's own interests, leaving them free to explore and learn as their interests lead.[12][13] "Unschooling" does not indicate that the child is not being educated, but that the child is not being "schooled", or educated in a rigid school-type manner. Holt asserted that children learn through the experiences of life, and he encouraged parents to live their lives with their child. Also known as interest-led or child-led learning, unschooling attempts to follow opportunities as they arise in real life, through which a child will learn without coercion. An unschooled child may utilize texts or classroom instruction, but these are not considered central to education. Holt asserted that there is no specific body of knowledge that is, or should be, required of a child.[14]

"Unschooling" should not be confused with "deschooling," which may be used to indicate an anti-"institutional school" philosophy, or a period or form of deprogramming for children or parents who have previously been schooled.

Both unschooling and natural learning advocates believe that children learn best by doing; a child may learn reading to further an interest about history or other cultures, or math skills by operating a small business or sharing in family finances. They may learn animal husbandry keeping dairy goats or meat rabbits, botany tending a kitchen garden, chemistry to understand the operation of firearms or the internal combustion engine, or politics and local history by following a zoning or historical-status dispute. While any type of homeschoolers may also use these methods, the unschooled child initiates these learning activities. The natural learner participates with parents and others in learning together.

Homeschooling families usually have to absorb the total costs of their child's education.[16]

Homeschooling and college admissions

Parents choose to use standardized test scores to aid colleges in evaluating students. The College Board suggests that homeschooled students keep detailed records and portfolios.[17]

In the last several decades, US colleges and universities have become increasingly open to accepting students from diverse backgrounds, including home-schooled students.[18] According to one source, homeschoolers have now matriculated at over 900 different colleges and universities, including institutions with highly selective standards of admission such as the US military academies, Rice University, Harvard University, Stanford University, Cornell University, Brown University, Dartmouth College, and Princeton University.[19]

A growing number of homeschooled students are choosing dual enrollment, earning college credit by taking community college classes while in high school. Others choose to earn college credits through standardized tests such as the College Level Examination Program (CLEP).

Motivations

| Reason for homeschooling | Number of homeschooled students |

Percent | s.e. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Can give child better education at home | 415,000 | 48.9 | 3.79 |

| Religious reason | 327,000 | 38.4 | 4.44 |

| Poor learning environment at school | 218,000 | 25.6 | 3.44 |

| Family reasons | 143,000 | 16.8 | 2.79 |

| To develop character/morality | 128,000 | 15.1 | 3.39 |

| Object to what school teaches | 103,000 | 12.1 | 2.11 |

| School does not challenge child | 98,000 | 11.6 | 2.39 |

| Other problems with available schools | 76,000 | 9.0 | 2.40 |

| Child has special needs/disability | 69,000 | 8.2 | 1.89 |

| Transportation/convenience | 23,000 | 2.7 | 1.48 |

| Child not old enough to enter school | 15,000 | 1.8 | 1.13 |

| Parent's career | 12,000 | 1.5 | 0.80 |

| Could not get into desired school | 12,000 | 1.5 | 0.99 |

| Other reasons* | 189,000 | 22.2 | 2.90 |

According to a 2001 U.S. Census survey, 33% of homeschooling households cited religion as a factor in their choice. The same study found that 30% felt school had a poor learning environment, 14% objected to what the school teaches, 11% felt their children were not being challenged at school, and 9% cited morality.[20]

According to the U.S. DOE's "Homeschooling in the United States: 2003", 85 percent of homeschooling parents cited "the social environments of other forms of schooling" (including safety, drugs, sexual harassment, bullying and negative peer-pressure) as an important reason why they homeschool. 72 percent cited "to provide religious or moral instruction" as an important reason, and 68 percent cited "dissatisfaction with academic instruction at other schools."[13] 7 percent cited "Child has physical or mental health problem", 7 percent cited "Child has other special needs", 9 percent cited "Other reasons" (including "child's choice," "allows parents more control of learning" and "flexibility").[13]

Other reasons include more flexibility in educational practices for children with learning disabilities or illnesses, or for children of missionaries, military families, or otherwise traveling parents. Homeschooling is sometimes opted for the gifted student who is accelerated, or has a significant hobby or early career (i.e. acting, dancing or music).

Controversies and criticism

Philosophical and political opposition

Opposition to homeschooling comes from many sources, including some organizations of teachers and school districts. The National Education Association, a United States professional association and union representing teachers, opposes homeschooling.[21][22]

Opponents of homeschooling state several categories of concerns relating to homeschooling or its potential effects on society:

- Inadequate standards of academic quality and comprehensiveness;

- Reduced funding for public schools;

- Lack of socialization with peers of different ethnic and religious backgrounds;

- The potential for development of religious or social extremism;

- Children sheltered from mainstream society, or denied opportunities that are their right, such as social development;

- Potential for development of parallel societies that do not fit into standards of citizenship and the community.

Stanford University political scientist professor Rob Reich [8] (not to be confused with former U.S. Secretary of Labor, Robert Reich) wrote in The Civic Perils of Homeschooling (2002) that homeschooling can potentially give students a one-sided point of view, as their parents may, even unwittingly, block or diminish all points of view but their own in teaching. He also argues that homeschooling, by reducing students' contact with peers, reduces their sense of civic engagement with their community.[23]

Gallup polls of American voters have shown a significant change in attitude in the last twenty years, from 73% opposed to home education in 1985 to 54% opposed in 2001.[24]

Criticism of supportive achievement studies

Although there are some studies that show that homeschooled students can do well on standardized tests,[25] some of these studies compare voluntary homeschool testing with mandatory public-school testing. Homeschooled students in the United States are not subject to the testing requirements of the No Child Left Behind Act.[26] Some U.S. states require mandatory testing for homeschooled students, but others do not. Some states that require testing allow homeschooling parents to choose which test to use.[27] An exception are the SAT and ACT tests, where homeschooled and formally-schooled students alike are self-selecting; homeschoolers averaged higher scores on college entrance tests in South Carolina.[28] When testing is not required, students taking the tests are self-selected, which biases any statistical results.[29] Other test scores (numbers from 1999 data in a year 2000 article) showed mixed results, for example showing higher levels for homeschoolers in English (homeschooled 23.4 vs national average 20.5) and reading (homeschooled 24.4 vs national average 21.4) on the ACT, but mixed scores in math (homeschooled 20.4 vs national average 20.7 on ACT, although SAT math section was above average 535 homeschooled compared to 511 for national average of 1999) .[30] However, advocates of home education and educational choice counter with an input-output theory, pointing out that home educators expend only an average of $500–$600 a year on each student, in comparison to $9,000-$10,000 for each public school student through the United States, which raises a question about whether home-educated students would be especially dominant on tests if afforded access to an equal commitment of tax-funded educational resources.[31]

Potential for unmonitored child abuse

A Washington, D.C. mother who had withdrawn her four children from public school has been charged with their murder. It has been claimed that the homeschooling exemption in the District of Columbia allowed the abuse of the children to occur undetected.[32] Increased regulation of homeschooling in DC has been enacted in response to these events.[33] But some legal commentators have noted that child abuse occurs in public school and state social care systems, and that there is no evidence suggesting that abuse among homeschoolers is more pervasive or severe than the considerable dangers encountered in government institutions.[34]

International status and statistics

Homeschooling is legal in many countries. Countries with the most prevalent home education movements include Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Some countries have highly regulated home education programs as an extension of the compulsory school system; others, such as Germany[35] and Brazil, have outlawed it entirely. In other countries, while not restricted by law, homeschooling is not socially acceptable or considered undesirable and is virtually non-existent.

Africa

Kenya

- Status: Legal

Homeschooling is currently permitted in Kenya.[36]

South Africa

- Status: Multiple

Homeschooling is legal according to South African national law, but individual provinces have the authority to set their own restrictions.[37]

Americas

Argentina

- Status: Illegal

Brazil

- Status: Legal

Legal since 06/21/2010.

Canada

- Status: Legal

Meighan estimated the total number of homeschoolers in Canada, in 1995, to be 10,000 official and 20,000 unofficial.[38] Karl M. Bunday estimated, in 1995, based on journalistic reports, that about 1 percent of school-age children were homeschooled.[39] In April 2005, the total number of registered homeschool students in British Columbia was 3,068.[40] In Manitoba, homeschoolers are required to register with Manitoba Education, Citizenship and Youth. The number of homeschoolers is noted at over 1,500 in 2006; 0.5% of students enrolled in the public system.

United States

- Status: Legal

Public schools were gradually introduced into the United States during the course of the 19th century. These were for the purpose of educating the orphans who had no parents to educate them at home. This concept slowly spread until Massachusetts became the first state to issue a compulsory education law in 1789.[3] It was not until 1852 that the state established a "true comprehensive statewide, modern system of compulsory schooling."[3]

Prior to the introduction of public schools, many children were educated in private schools or in the home. During this period, illiteracy was common and many children were never properly educated.[41] It was common for literate parents to use books dedicated to educating children such as Fireside Education, Griswold, 1828, Warren Burton's Helps to Education in the Homes of Our Country,[42] 1863, and the popular McGuffey Readers, sometimes bolstered by local or itinerant teachers, as means and opportunity allowed.[11] Raymond Moore, among others, asserted that the United States was at the height of its national literacy under this informal system of tutelage, but such claims are difficult to prove.[43]

After the establishment of the Massachusetts system, other states and localities gradually began to provide public schools and to make attendance mandatory as they too had problems with the question of how to educate the orphans. In 1912, A.A. Berle of Tufts University (not to be confused with the Adolf Berle who was a delegate to the Paris Peace Conference) asserted in his book The School in Your Home that the previous 20 years of mass education had been a failure and that he had been asked by hundreds of parents how they could teach their children at home.[11]

In "The Condition of Education 2000-2009," The National Center for Education Statistics of the United States Department of Education reports that In 2007, the number of homeschooled students was about 1.5 million, an increase from 850,000 in 1999 and 1.1 million in 2003.[44] The percentage of the school-age population that was homeschooled increased from 1.7 percent in 1999 to 2.9 percent in 2007. The increase in the percentage of homeschooled students from 1999 to 2007 represents a 74 percent relative increase over the 8-year period and a 36 percent relative increase since 2003. In 2007, the majority of homeschooled students received all of their education at home (84 percent), but some attended school up to 25 hours per week.

NCES also reports that White students constituted the majority of homeschooled students (77 percent). White students (3.9 percent) had a higher homeschooling rate than Blacks (0.8 percent) and Hispanics (1.5 percent), but were not measurably different from students from other racial/ethnic groups (3.4 percent). Students in two-parent households made up 89 percent of the homeschooled population, and those in two-parent households with one parent in the labor force made up 54 percent of the homeschooled population. The latter group of students had a higher homeschooling rate than their peers: 7 percent, compared with 1 to 2 percent of students in other family circumstances. In 2007, students in households earning between $25,001 and $75,000 per year had higher rates of homeschooling than their peers from families earning $25,000 or less a year.

Parents gave NCES many different reasons for homeschooling their children. In 2007, the most common reason they gave as the most important was a desire to provide religious or moral instruction (36 percent of students). This reason was followed by a concern about the school environment (such as safety, drugs, or negative peer pressure) (21 percent), dissatisfaction with academic instruction (17 percent), and "other reasons" including family time, finances, travel, and distance (14 percent). Parents of about 7 percent of homeschooled students cited the desire to provide their child with a nontraditional approach to education as the most important reason for homeschooling, and the parents of another 6 percent of students cited a child's health problems or special needs.

Statistically, the typical American homeschooling parents are married, homeschool their children primarily for religious or moral reasons, and are almost twice as likely to be Evangelical than the national average. They average three or more children, and typically the mother stays home to care for them.[13][20][45][46]

According to Barna, homeschoolers are almost twice as likely to be evangelical as the national average (15 percent vs 8 percent), and that 91 percent describe themselves as Christian, although only 49 percent can be classified as "born again Christians." It found they were five times more likely to describe themselves as "mostly conservative" on political matters than as "mostly liberal," although only about 37 percent chose "mostly conservative", and were "notably" more likely than the national average to have a high view of the Bible and hold orthodox Christian beliefs.

| Did not finish high school | High school graduate only | Some college, no degree | Associate degree | Bachelors degree | Masters degree | Doctorate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homeschool fathers | 1.2% | 9.3% | 16.4% | 6.9% | 37.6% | 19.8% | 8.8% |

| Males nationally | 18.1 | 32.0 | 19.5 | 6.4 | 15.6 | 5.4 | 3.1 |

| Homeschool mothers | 0.5 | 11.3 | 21.8 | 9.7 | 47.2 | 8.8 | 0.7 |

| Females nationally | 17.2 | 34.2 | 20.2 | 7.7 | 14.8 | 4.5 | 1.3 |

Lawrence Rudner's (University of Maryland) 1998 study shows that homeschool parents have a higher income than average (1.4 times by one estimate),[46] and are more likely to have an advanced education. Rudner found that homeschooling parents tend to have more formal education than parents in the general population; that the median income for homeschooling families ($52,000) is significantly higher than that of all families with children in the United States ($36,000); that 98% of homeschooled children live in "married couple families"; that 77% of homeschool mothers do not participate in the labour force, whereas 98% of homeschooling fathers do participate in the labour force; and that median annual expenses for educational materials are approximately $400 per homeschool student.[48]

A 2001 study by Dr. Clive Belfield states that the average homeschooling parent is a woman with a college degree. Belfield estimates annual homeschooling costs to be approximately $2,500 per child[49] Some studies suggest per-child spending of a lower amount, but virtually all studies suggest home-school expenditure per child is far less than per-student expenditure in public schools, which tends to average $9,000-$10,000 in the United States.[31]

Asia

People's Republic of China

- Status: Deemed illegal for citizens, but no restrictions for foreign students.

There are no accurate statistics on homeschooling in the People's Republic of China.

The Compulsory Education Law states that the community, schools and families shall safeguard the right to compulsory education of school-age children and adolescents. And, compulsory education is defined as attending a school, which is holding a schooling licence granted by the government. Therefore, homeschooling is deemed to be illegal. The Law does not apply to non-citizen children(i.e. those with foreign passports).

However, due to the large population of hundreds of millions of migration workers, alongside with their children, it rarely happens that the government inspects if a child is attending a licensed school or not. Thus, there usually is no punishment to parents who homeschool their children.

An organization called Shanghai Home-School Association was launched in September 2003.[50]

Hong Kong

- Status: Illegal

Attendance at school is compulsory and free for students aged six to fifteen in Hong Kong. Parents who fail to send their children to school can be jailed for 3 months and fined HK$10000. In 2000, a man named Leung Jigwong (梁志光) disagreed with Hong Kong's education policy and refused to send his 9-year-old daughter to school. Instead, he taught her Chinese, English, French, Mathematics and The Art of War at home. After 2.5 years of discussion, the Education Department finally served an "attendance order" on him and his child was required to attend a normal school.[51][52][53]

India

Japan

The legal position is complex; as homeschooling is uncommon, local officials may claim it is illegal but this is not actually the case.[54] Over 100,000 children refuse school, but the number of homeschoolers is much smaller, though it is increasing.

Indonesia

- Status: Legal

Homeschooling in Indonesia (Indonesian: Pendidikan Rumah) is regulated under National Education System 2003 under division of informal education.[55] This enables the children of Homeschooling to attend an equal National Tests to obtain an "Equivalent Certificate".[56] The homeschooling is recently becoming a trend in upper-middle to upper class families with highly educated parents with capability to provide better tutoring[57] or expatriate families living far away from International School. Since 2007 the Indonesia's National Education Department took efforts in providing Training for Homeschooling Tutors and Learning Media[58] even though the existence of this community is still disputed by other Non Formal education operators.[59] school.

Taiwan

- Status: Legal

Homeschooling in Taiwan, Republic of China is legally recognized since 1982[60] and regulated as a possible form of special education since 1997.[61]

Europe

Austria

- Status: Legal

Homeschooling is legal in Austria. However, every homeschooled child is required to take an exam, administered four times per year, to ensure that he or she is being educated at an appropriate level. If the child fails the test, he or she must attend a state school the following year.[35]

Belgium

- Status: Legal

The child has to be registered as home educated. In Wallonië (French speaking part of the country) they are tested at 8, 10, 12, 14.

The tests are new and there is still a lot of confusion on the tests and the legal situation around them. In Flanders (Dutch speaking part of the country) the law is different : the tests are not compulsory.

Czech Republic

- Status: Legal

Homeschooling has been legal since 2005.

Denmark

- Status: Legal

It follows from § 76 in the Danish constitution that homeschooling is legal.[62]

Finland

- Status: Legal

In Finland homeschooling is legal but unusual. The parents are responsible for the child getting the compulsory education and the advancements are supervised by the home municipality. The parents have the same freedom to make up their own curriculum as the municipalities have regarding the school, only national guiding principles of the curriculum have to be followed.

Choosing homeschooling means that the municipality is not obliged to offer school books, health care at school, free lunches or other privileges prescribed by the law on primary education, but the ministry of education reminds they may be offered. The parents should be informed of the consequences of the choice and the arrangements should be discussed.[63][64]

France

- Status: Legal

In France, homeschooling is legal and requires the child to be registered with two authorities, the 'Inspection Académique' and the local town hall (Mairie). Children between the ages of 6 and 16 who are not enrolled in recognized correspondence courses are subject to annual inspection.[65][66]

The inspection is carried out to check that the child's knowledge has progressed as a comparison from the previous inspection; sometimes it involves written tests, though those are illegal, in both French and Mathematics, the first of which is used as a benchmark to check what level the child is. The tests are carried out with the anticipation that the child will progress in ability as she/he ages, thus they are designed to measure development with age, rather than as a comparison to say a school child of a similar age.

Germany

- Status: Illegal

Homeschooling is illegal in Germany (with rare exceptions). Children cannot be exempted from formal school attendance on religious grounds. The requirement for children from an age of about 6 years through the age of 16 to attend school has been upheld, on challenge from parents, by the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany. Penalties against parents who force their children to break the mandatory attendance laws may include fines (around €5,000), actions to revoke the parents' custody of their children, and jail time.

Some parents of a baptist and evangelical background have objected to the rule on the grounds of the secular education received in state schools, and what they see as anti-Christian teaching. At least one family has sought and received political asylum in the United States as a result.[67]

Greece

- Status: Illegal

Hungary

- Status: Legal

The Hungarian laws allow homeschoolers to teach their children as private students at home as long as they generally follow the state curriculum and have children examined twice a year.

Republic of Ireland

- Status: Legal

From 2004 to 2006, 225 children had been officially registered with the Republic of Ireland's National Education Welfare Board, which estimated there may be as many as 1500–2000 more unregistered homeschoolers.[68] The right to a home education is guaranteed by the Constitution of Ireland.[69]

Italy

- Status: Legal

In Italy, homeschooling (called Istruzione parentale in Italian) is legal but not common: children must be registered to the school where they will take their final exams, and parents must justify their decision to homeschool their children at the beginning of every year.[70]

Netherlands

- Status: Generally Illegal

In the Netherlands every child is subject to compulsory education from his/her fifth birthday. The exemptions are extended on the basis of a clause in the law exempting parents from sending their child to school if they object to the "direction" of the education of all schools within a reasonable distance to their home.[71][72]

Norway

- Status: Legal

Homeschooling is legal.[73]

Poland

- Status: Legal

Homeschooling is only allowed on highly regulated terms. Every child must be enrolled in a public school, but with school principal may but isn't obliged to allow homeschooling. Homeschooled children are required to pass annual exams covering material in school curriculum, and failure on an exam automatically withdraws homeschooling permit.[74]

Portugal

- Status: Legal

Homeschooling is Legal.[75]

Russia

- Status: Legal

The number of homeschoolers in Russia has tripled since 1994 to approximately 1 million. Russian homeschoolers are attached to an educational institution where they have the right to access textbooks and teacher support, and where they pass periodic appraisals of their work. The State is obliged to pay the parents cash equal to the cost of educating the child at the municipal school.

Slovenia

- Status: Legal

The number of people homeschooling in Slovenia has been increasing over the years.[76] The Slovenian term for homeschooling is "izobraževanje na domu".

Slovak Republic

- Status: Legal

Homeschooling is legal with obstacles in Slovak Republic. Child's tutor is required to have a degree with major in primary school education.[77]

Spain

- Status: Generally illegal

In Spain, homeschooling is illegal. However, the regional government of Catalonia announced in 2009 that parents would be allowed to homeschool their children up to 16 years.[78]

Sweden

- Status: Generally illegal

Children have to attend school from the age of 7. Homeschooling as an afterschool activity is allowed when attending school.[79]

It is not technically illegal. It is, however, very difficult to get approved by the county in which one lives. Stockholm is in general more difficult to get approval than elsewhere in the country. Sweden is currently working on a law that would restrict homeschooling even further. A recent court case has supported restrictions on parents, even those with teacher-training, to educate their own child.[80]

Switzerland

- Status: Legal

Requirements vary from Canton to Canton. Over 200 families currently homeschool [81][82]

Turkey

- Status: Illegal

Ukraine

- Status: Illegal

A school for the disabled with online technology and online сonsultations for parents whose children with disabilities

United Kingdom

- Status: Legal (England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland have their own education laws each with slight variations regarding education otherwise than at school.)

Education provided outside a formal school system is primarily known as Home Education within the United Kingdom, the term Homeschooling is occasionally used for those following a formal, structured style of education – literally schooling at home. To distinguish between those who are educated outside of school from necessity (e.g. from ill health, or a working child actor) and those who actively reject schooling as a suitable means of education the term Elective Home Education is used.[83]

The Badman Review in 2009 stated that "approximately 20,000 home educated children and young people are known to local authorities, estimates vary as to the real number which could be in excess of 80,000."[84]

Oceania

Australia

- Status: Legal

The Australian census does not track homeschooling families, but Philip Strange of Home Education Association, Inc. very roughly estimates 15,000.[85] In 1995, Roland Meighan of Nottingham School of Education estimated some 200,000 families homeschooling in Australia.[38]

In 2006, Victoria passed legislation[86] requiring the registration of children up to the age of 16 and increasing the school leaving age to 16 from the previous 15, undertaking home education (registration is optional for those age of 16–17 but highly recommended). The Victorian Registration and Qualifications Authority (VRQA) is the registering body.[87][88]

New Zealand

- Status: Legal

Karl M. Bunday cites the New Zealand TV program "Sixty Minutes" (unrelated to the U.S. program), as stating in 1996 that there were 7,000 school-age children being homeschooled.[89] Philip Strange of the Australian Home Education Association Inc. quotes "5274 registered home educated students in 3001 families" in 1998 from the New Zealand Ministry of Education.[85]

"At 1 July 2007 there were 6,473 homeschooled students recorded on the Ministry of Education's homeschooling database, which represents less than one per cent of total school enrolments at July 2007. These students belonged to 3,349 families."[90]

Supportive research

- The studies cited in this section have been criticised for selection bias and other problems, see below: Criticism of supportive achievement studies.

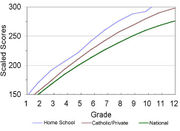

Test results

Numerous studies have found that homeschooled students on average outperform their peers on standardized tests.[91] Homeschooling Achievement, a study conducted by National Home Education Research Institute (NHERI), supported the academic integrity of homeschooling. Among the homeschooled students who took the tests, the average homeschooled student outperformed his public school peers by 30 to 37 percentile points across all subjects. The study also indicates that public school performance gaps between minorities and genders were virtually non-existent among the homeschooled students who took the tests.[92]

New evidence has been found that homeschooled children are getting higher scores on the ACT and SAT tests. A study at Wheaton College in Illinois showed that the freshmen that were homeschooled for high school scored fifty-eight points higher on their SAT scores than those students who attended public or private schools. Most colleges look at the ACT and SAT scores of homeschooled children when considering them for acceptance to a college. On average, homeschooled children score eighty-one points higher than the national average on the SAT scores.

Social research

In the 1970s Raymond S. and Dorothy N. Moore conducted four federally funded analyses of more than 8,000 early childhood studies, from which they published their original findings in Better Late Than Early, 1975. This was followed by School Can Wait, a repackaging of these same findings designed specifically for educational professionals.[93] Their analysis concluded that, "where possible, children should be withheld from formal schooling until at least ages eight to ten."

Their reason was that children, "are not mature enough for formal school programs until their senses, coordination, neurological development and cognition are ready." They concluded that the outcome of forcing children into formal schooling is a sequence of "1) uncertainty as the child leaves the family nest early for a less secure environment, 2) puzzlement at the new pressures and restrictions of the classroom, 3) frustration because unready learning tools – senses, cognition, brain hemispheres, coordination – cannot handle the regimentation of formal lessons and the pressures they bring, 4) hyperactivity growing out of nerves and jitter, from frustration, 5) failure which quite naturally flows from the four experiences above, and 6) delinquency which is failure's twin and apparently for the same reason."[94] According to the Moores, "early formal schooling is burning out our children. Teachers who attempt to cope with these youngsters also are burning out."[94] Aside from academic performance, they think early formal schooling also destroys "positive sociability", encourages peer dependence, and discourages self worth, optimism, respect for parents, and trust in peers. They believe this situation is particularly acute for boys because of their delay in maturity. The Moore's cited a Smithsonian Report on the development of genius, indicating a requirement for "1) much time spent with warm, responsive parents and other adults, 2) very little time spent with peers, and 3) a great deal of free exploration under parental guidance."[94] Their analysis suggested that children need "more of home and less of formal school" "more free exploration with... parents, and fewer limits of classroom and books," and "more old fashioned chores – children working with parents – and less attention to rivalry sports and amusements."[94]

John Taylor later found, using the Piers-Harris Children's Self-Concept Scale, "while half of the conventionally schooled children scored at or below the 50th percentile (in self-concept), only 10.3% of the home-schooling children did so."[95] He further stated that "the self-concept of home-schooling children is significantly higher (and very much so statistically) than that of children attending the conventional school. This has implications in the areas of academic achievement and socialization, to mention only two. These areas have been found to parallel self-concept. Regarding socialization, Taylor's results would mean that very few home-schooling children are socially deprived. He states that critics who speak out against homeschooling on the basis of social deprivation are actually addressing an area which favors homeschoolers.[95]

In 2003, the National Home Education Research Institute conducted a survey of 7,300 U.S. adults who had been homeschooled (5,000 for more than seven years). Their findings included:

-

- Homeschool graduates are active and involved in their communities. 71% participate in an ongoing community service activity, like coaching a sports team, volunteering at a school, or working with a church or neighborhood association, compared with 37% of U.S. adults of similar ages from a traditional education background.

-

- Homeschool graduates are more involved in civic affairs and vote in much higher percentages than their peers. 76% of those surveyed between the ages of 18 and 24 voted within the last five years, compared with only 29% of the corresponding U.S. populace. The numbers are even greater in older age groups, with voting levels not falling below 95%, compared with a high of 53% for the corresponding U.S. populace.

-

- 58.9% report that they are "very happy" with life, compared with 27.6% for the general U.S. population. 73.2% find life "exciting", compared with 47.3%.[96]

Other research

UK: Paula Rothermel ROTHERMEL, P. (2002) Home education: Aims, Practices and Outcomes. PhD thesis, University of Durham.[97] ROTHERMEL, P. (2004) Home education: comparison of home and school educated children on PIPS Baseline Assessments, Journal of Early Childhood Research Issue 5. ROTHERMEL, P. (2005) Can we classify motives for home education? Evaluation and Research in Education, 17(2)(3).

See also

- List of homeschooled people

- Alternative education

- Homeschool Legal Defense Association

- Schoolhouse Home Education Association

- Unschooling

- Secular Homeschooling (magazine)

- Legality of Homeschooling

- Parenting styles

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 A. Distefano, K. E. Rudestam, R. J. Silverman (2005) Encyclopedia of Distributed Learning (p221) ISBN 0761924515

- ↑ HSLDA. "Homeschooling in New York: A legal analysis" (PDF). http://www.hslda.org/laws/analysis/New_York.pdf. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Education: Free and Compulsory – Mises Institute

- ↑ "Education" Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th ed., p. 959.

- ↑ History

- ↑ History of Alternative Education in the United States

- ↑ Removing Classrooms from the Battlefield: Liberty, Paternalism, and the Redemptive Promise of Educational Choice, 2008 BYU Law Review 377, 386 n.30

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Christine Field. The Old Schoolhouse Meets Up with Patrick Farenga About the Legacy of John Holt

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Better Late Than Early, Raymond S. Moore, Dorothy N. Moore, Seventh Printing, 1993

- ↑ Better Late Than Early, Raymond S. Moore, Dorothy N. Moore, 1975

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 http://www.hsc.org/professionals/briefhistory

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 A Conversation with John Holt (1980)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Homeschooling in the United States: 2003 – Executive Summary

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 HSLDA | Homeschooling-State

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Unit Study Approach. TheHomeSchoolMom.com.

- ↑ NCSPE FAQ 2003, What are home-schools?

- ↑ Winnick, Pamela R. (2000-05-01). "Homeschooled students take unorthodox route to become top college candidates". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. http://www.post-gazette.com/regionstate/20000501homeschool5.asp.

- ↑ "Homeschoolers find university doors open". The Boston Globe. 2007-03-06. http://www.boston.com/news/education/higher/articles/2007/03/06/homeschoolers_find_university_doors_open/.

- ↑ A. Distefano et al. (2005) Encyclopedia of Distributed Learning (p222) ISBN 1597815721

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Kurt J. Bauman. Home-Schooling in the United States: Trends and Characteristics. U.S. Census Bureau. August 2001.

- ↑ Lines, Patricia M.. "Homeschooling". Kidsource. http://www.kidsource.com/kidsource/content2/homeschooling.k12.3.html. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ↑ Lips, Dan; Feinberg, Evan (2008-04-03). "Homeschooling: A Growing Option in American Education". Heritage Foundation. http://www.heritage.org/Research/education/bg2122.cfm. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ↑ The civic perils of homeschooling Author: Rob Reich Journal: Educational Leadership (Alexandria) Pub.: 2002-04 Volume: 59 Issue: 7 Pages: 56

- ↑ CEPM – Trends and Issues: School Choice

- ↑ HSLDA | Academic Statistics on Homeschooling

- ↑ White House News & Policies No Child Left Behind

- ↑ Oregon Department of Education Guidelines for Homeschooling (Section 3.3)

- ↑ Homeschool Legal Defense Association. "Academic Statistics on Homeschooling." http://www.hslda.org/docs/nche/000010/200410250.asp

- ↑ Katherine Pfleger. School's out The New Republic. Washington: April 6, 1998. 218(14):11-12.

- ↑ Golden, Daniel. "Home-Schooled Kids Defy Stereotypes, Ace SAT Test." The Wall Street Journal 11 February 2000. http://www.oakmeadow.com/resources/articles/WSJArticle.htm

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Fostering Educational Innovation in Choice-Based Multi-Venue and Government Single-Venue Settings." http://sutherlandinstitute.org/uploads/Choice-based_Educational_Innovation.pdf (pp. 32 n.21; 35-36 n.27; 42 n.57; 44 n.66)

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/12/us/12bodies.html?ref=us Jane Gross Lack of Supervision Noted in Deaths of Home-Schooled New York Times, January 12, 2008

- ↑ http://newsroom.dc.gov/show.aspx/agency/seo/section/2/release/14329 DC State Board of Education Approves Homeschooling Regulations July 16, 2008

- ↑ People v. Bennett: Analytic Approaches to Recognizing a Fundamental Parental Right Under the Ninth Amendment, 1996 BYU Law Review 186, 227-34

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Spiegler, Thomas (2003). "Home education in Germany: An overview of the contemporary situation" (PDF). Evaluation and Research in Education 17: 179–90. doi:10.1080/09500790308668301. http://www.multilingual-matters.net/erie/017/0179/erie0170179.pdf.

- ↑ HSLDA | Home Schooling - Kenya

- ↑ HSLDA | Home Schooling - South Africa

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Home-based education effectiveness research and some of its implications (pdf document)

- ↑ Homeschooling Is Growing Worldwide (Learn in Freedom!)

- ↑ BC Ministry of Education

- ↑ An 1872 map of illiteracy in the United States shows that illiteracy was most common in the southern states which were late in adopting compulsory schooling. See: Illiteracy in the United States 1872, From The Statistics of the Population of the United States, Compiled from the Original Returns of the Ninth Census, 1872. Although this illiteracy was partly due to white resistance to education of blacks prior to Reconstruction, the map shows that southern locations without large populations of former slaves also had high levels of illiteracy. Public schools were first introduced in many parts of the South during Reconstruction.

- ↑ Cornell University Making of America

- ↑ Dr. Raymond Moore, Home Grown Kids, 1981

- ↑ National Center for Education Statistics, "Condition of Education 2000-2009" [1]

- ↑ Homeschooling in the United States: 2003 – The Characteristics of Homeschooled and Nonhomeschooled Students

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Homeschool Statistics. Homeschool Legal Defense Association.

- ↑ EPAA Vol. 7 No. 8 Rudner: Homeschool Students, 1998

- ↑ Scholastic Achievement and Demographic Characteristics of Homeschool Students in 1998, Lawrence M. Rudner, University of Maryland, College Park, EDUCATION POLICY ANALYSIS ARCHIVES, Volume 7, Number 8, March 23, 1999, ISSN 1068-2341 online article Scholastic Achievement and Demographic Characteristics of Homeschool Students in 1998, Lawrence M. Rudner, Table 2.12

- ↑ MSN Money. Home-school costs can add up fast. 2001 study by Dr. Clive Belfield, professor of economics at Queens College, City University of New York

- ↑ Yang Yang. "Homeschooling gains favour". http://app1.chinadaily.com.cn/star/2004/1209/fo7-1.html.

- ↑ http://www.epochtimes.com/b5/2/8/20/n209638p.htm

- ↑ http://www.edb.gov.hk/index.aspx?nodeid=136&langno=1&UID=10546

- ↑ http://www.hklii.org/hk/legis/en/ord/279/s78.html

- ↑ http://www.asahi-net.or.jp/~ja8i-brtl/Legal_Issues.htm

- ↑ :http://www.inherent-dikti.net/files/sisdiknas.pdf

- ↑ http://www.jugaguru.com/article/49/tahun/2006/bulan/12/tanggal/11/id/279/

- ↑ http://www.jugaguru.com/news/43/tahun/2008/bulan/04/tanggal/28/id/720/

- ↑ http://www.jugaguru.com/news/31/tahun/2007/bulan/12/tanggal/17/id/640/

- ↑ http://www.jugaguru.com/expression/comment/427/2/

- ↑ (Chinese) 強迫入學條例 (Compulsory School Law)

- ↑ (Chinese)特殊教育法 (The Act of Special Education)

- ↑ Danmark er der undervisningspligt og ikke skolepligt, the Danish Ministry of Education

- ↑ Law on primary education (Swedish), 26 §

- ↑ Ministery of Education: Homeschooling (Swedish)

- ↑ HSLDA: Families in France Turn to Homeschooling Despite Heavy Regulation (English)

- ↑ Les Enfants d'Abord : Frequently Asked Questions (English)

- ↑ "US grants home schooling German family political asylum" - The Guardian, 27 Jan 2010

- ↑ The National Education (Welfare) Board Ireland

- ↑ The constitutions of Poland and Ireland give citizens the right to a home education

- ↑ Ministero della Pubblica Istruzione, in Italian

- ↑ Thuisonderwijs

- ↑ Nederlandse Vereniging voor Thuisonderwijs (NVvTO)

- ↑ Lov om grunnskolen og den vidaregåande opplæringa 1 ch. 2 §, 2 ch. 1 § (no), Summary on the site of the Norwegian homeschooling association (en)

- ↑ Ustawa z dnia 7 września 1991 r. o systemie oświaty. [2], Ustawa z dnia 19 marca 2009 r. o zmianie ustawy o systemie oświaty oraz o zmianie niektórych innych ustaw [3] (pl)

- ↑ Lei 85/2009 [4] (pt)

- ↑ Uradni list Republike Slovenije

- ↑ ZÁKON 245/2008 Zz z 22. mája 2008 o výchove a vzdelávaní (školský zákon) §23-25

- ↑ El País: Cataluña abre la vía para formar a los hijos en casa

- ↑ Skollagen (Swedish), 3 ch. 1–2 §

- ↑ [5] (English),

- ↑ HSLDA Switzerland

- ↑ Homeschool Association of Switzerland

- ↑ UK Government guidelines on Elective home education

- ↑ Review of Elective Home Education in England page 2

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Home Education Association Inc. (Australia) – How Many Home Educators in Australia

- ↑ The Education Training and Reform Act (2006), available online at the Australasian Legal Information Institute's website [6]

- ↑ [7] Victorian Registration and Qualifications Authority website

- ↑ Homeschooling on the VRQA site

- ↑ Homeschooling in The United Kingdom (Learn in Freedom!)

- ↑ Ministry of Education: Statistics on Homeschooling

- ↑ HSLDA | Academic Statistics on Homeschooling

- ↑ HSLDA | Homeschooling Achievement

- ↑ Better Late Than Early, Raymond S. Moore, Dorothy N. Moore, Seventh Printing, 1993, addendum

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 94.2 94.3 Raymond S. Moore, Dorothy Moore. When Education Becomes Abuse: A Different Look at the Mental Health of Children

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Self-Concept in home-schooling children, John Wesley Taylor V, Ph.D., Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI

- ↑ HSLDA | Homeschooling Grows Up

- ↑ pjrothermel.com/phd/Home.htm

External links

- A history of the modern homeschool movement, from the Cato Institute.

- National Home Education Research Institute NHERI produces research about homeschooling and sponsors the peer-reviewed academic journal Homeschool Researcher.

- Home Education Network of Victoria, Australia

- Home Education Foundation, New Zealand

- The National Independent Study Accreditation Council

- Home School Legal Defense Association

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||