History of the United States (1789–1849)

| History of the United States | |

|---|---|

This article is part of a series |

|

| Timeline | |

| Pre-Colonial period | |

| Colonial period | |

| 1776–1789 | |

| 1789–1849 | |

| 1849–1865 | |

| 1865–1918 | |

| 1918–1945 | |

| 1945–1964 | |

| 1964–1980 | |

| 1980–1991 | |

| 1991–present | |

| Topic | |

| Westward expansion | |

| Overseas expansion | |

| Diplomatic history | |

| Military history | |

| Technological and industrial history | |

| Economic history | |

| Cultural history | |

| Civil War | |

| History of the South | |

| Civil Rights (1896–1954) | |

| Civil Rights (1955–1968) | |

| Women's history | |

|

United States Portal |

This article covers the history of the United States from 1789 through 1849, the period of westward expansion.

After the election of George Washington as the first president in 1789, Congress passed the first of many laws organizing the government and adopted a bill of rights as 10 amendments to the new constitution; these amendments are the U.S. Bill of Rights. During much of early U.S. there was no popular vote count in presidential elections.

President Washington took action to establish the Executive Branch of the United States Government. Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1789, which established the entire federal judiciary, including the Supreme Court.

The 1790s were highly contentious, as the First Party System emerged in the contest between Alexander Hamilton and his Federalist party, and Thomas Jefferson and his Republican party. Washington and Hamilton were building a strong national government, with a broad financial base, and the support of merchants and financiers throughout the country. Jeffersonians oppose the new national Bank, the Navy, and federal taxes. The Federalists favored Britain, which was embattled in a series of wars with France. Jefferson's victory in 1800 opened the era of Jeffersonian democracy, and doomed the upper-crust federalists to increasingly marginal roles.

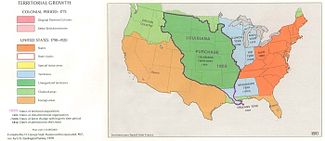

The Louisiana Purchase, in 1803 opened vast Western expanses of fertile land, just right for the yeomen farmers who Jefferson championed.

The War of 1812 against Britain was fought to uphold American honor, which it accomplished. Despite incompetent government management, and a series of defeats early on, Americans found new generals like Andrew Jackson, William Henry Harrison, and Winfield Scott, who repulsed British invasions and broke the alliance between the British and the Indians that held up settlement of the Old Northwest. In the 1830s, the Federal government forcibly deported the Southeastern tribes to reservations in the west.

The spread of democracy opened the ballot box to nearly all white men, allowing the Jacksonian democracy to dominate politics during the Second Party System. Whigs, representing wealthier planters merchants financiers and professionals, wanted to modernize the society, using tariffs and federally funded internal improvements; they were blocked by the Jacksonians, who closed down the national Bank in 1830s. The Jacksonians wanted expansion--that is "Manifest Destiny"-- into new lands that would be occupied by farmers and planters. Thanks to the annexation of Texas, the defeat of Mexico in war, and a compromise with Britain, the western third of the nation rounded out the continental United States by 1848.

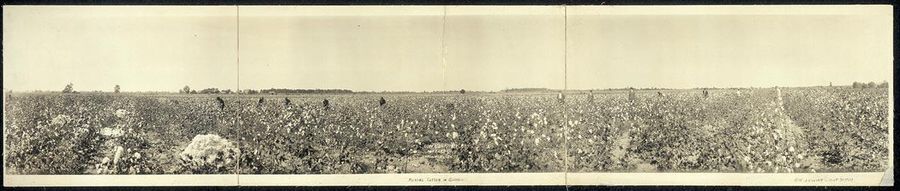

Meanwhile economic and modernization proceeded rapidly, thanks to highly profitable cotton crops in the south, industries in the Northeast, and a fast developing transportation infrastructure. Breaking loose from European models, the Americans developed their own high culture, notably in literature and in higher education. The Second Great Awakening brought revivals across the country, forming new denominations and greatly increasing church membership, especially among Methodists and Baptists. By the 1840s increasing numbers of immigrants were arriving from Europe, especially British, Irish, and Germans. Many settled in the cities, which were starting to emerge as a major factor in the economy and society.

The Whigs had warned that annexation of Texas would lead to a crisis over slavery, and they were proven right by the turmoil of the 1850s that led to civil war.

Contents |

Federalist Era

Washington Administration: 1789–1797

.jpg)

George Washington, a renowned hero of the American Revolutionary War, commander of the Continental Army, and president of the Constitutional Convention, became the first President of the United States under the new U.S. Constitution

Perhaps the most popular figure in U.S. political history at the time, Washington was proclaimed the "Father of the Country", and won the 1789 election with virtually no opposition. He won the electoral vote unanimously, something that has not occurred since. There was no popular vote for Washington's election.

Under Washington's presidency, the first U.S. Census was taken in 1790, fulfilling the requirements of Section II in Article One of the Constitution. The census determined the number of congressional districts in each state; from each district, a congressman was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives.

Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1789, which established the entire federal judiciary. At the time, the act provided for a Supreme Court of six justices, three circuit courts, and 13 district courts. It also created the offices of U.S. Marshal, Deputy Marshal, and District Attorney. In addition, it established the Supreme Court as the mediator of all disputes between states and the federal government concerning conflicting state and federal laws.

The Compromise of 1790 helped delay a major conflict over slavery between the Northern and Southern states.

The Whiskey Rebellion in 1794—when settlers in the Monongahela Valley of western Pennsylvania protested against a federal tax on liquor and distilled drinks—was the first serious test of the federal government. Washington ordered federal marshals to serve court orders requiring the tax protesters to appear in federal district court. By August 1794, the protests became dangerously close to outright rebellion, and on August 7, several thousand armed settlers gathered near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Washington then invoked the Militia Law of 1792 to summon the militias of several states. A force of 13,000 men was organized, roughly the size of the entire army in the Revolutionary War. The army marched to Western Pennsylvania and quickly suppressed the revolt. Two leaders of the revolt were convicted of treason but pardoned by Washington. This response marked the first time under the new Constitution that the federal government had used strong military force to exert authority over the nation's citizens.

Many other major policies and decisions of Washington's two terms involved two of his cabinet members—Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson—whose different ideologies corresponded with the formation of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, respectively. Although Washington warned against political parties in his farewell address, many felt that by the end of his term he was a Federalist. His Whiskey Rebellion suppression seems to indicate this.

In Washington's farewell address he prophetically warned of standing armies, and their threat to democracy.

Despite Washington's desire to follow a policy of neutrality, the United States would grow to have a rich diplomatic history.

Adams Administration: 1797-1801

Washington retired in 1797, firmly declining to serve for more than eight years as the nation's head. Vice President John Adams was elected the new President. Even before he entered the presidency, Adams had quarreled with Alexander Hamilton—and thus was handicapped by a divided Federalist party.

These domestic difficulties were compounded by international complications: France, angered by John Jay's recent treaty with Britain, used the British argument that food supplies, naval stores and war material bound for enemy ports were subject to seizure by the French navy. By 1797, France had seized 300 American ships and had broken off diplomatic relations with the United States. When Adams sent three other commissioners to Paris to negotiate, agents of Foreign Minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand (whom Adams labeled "X, Y and Z" in his report to Congress) informed the Americans that negotiations could only begin if the United States loaned France $12 million and bribed officials of the French government. American hostility to France rose to an excited pitch. The so-called "XYZ Affair" led to the enlistment of troops and the strengthening of the fledgling United States Navy.

In 1799, after a series of naval battles with the French (known as the Quasi-War), war seemed inevitable. In this crisis, Adams ignored Hamilton's advice to go to war and sent three new commissioners to France. Napoleon, who had just come to power, received them cordially, and the danger of conflict subsided with the negotiation of the Convention of 1800, which formally released the United States from its 1778 wartime alliance with France. However, reflecting American weakness, France refused to pay $20 million in compensation for American ships seized by the French navy.

Hostility to France and to their internal American political opponents led the Federalist-controlled Congress to pass, and Adams to sign, the Alien and Sedition Acts, which had severe repercussions for American civil liberties. The Naturalization Act, which changed the residency requirement for citizenship from five to 14 years, was targeted at Irish and French immigrants suspected of supporting the Democratic-Republican Party. The Alien Act, operative for only two years, gave the President the power to expel or imprison aliens in time of war. The Sedition Act proscribed writing, speaking or publishing anything of "a false, scandalous and malicious" nature against the President or Congress. The few convictions won under the Sedition Act only created martyrs to the cause of civil liberties and aroused support for the Democratic-Republicans.

The acts met with resistance: Jefferson and James Madison secretly wrote the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions by the legislatures of the two states in November and December 1798. According to the resolutions, states could legally block and "nullify" unconstitutional federal laws. However, all the other states rejected this proposition, and nullification -- or it was as it was called, the "principle of 98" -- became the preserve of a faction of the Republicans called the Quids

Thomas Jefferson

By 1800 Americans were ready for change. Under Washington and Adams the Federalists had established a strong government, but sometimes failed to honor the principle that the American government must be responsive to the will of the people; they had followed policies that alienated large groups of Americans. For example, in 1798, to pay for the national debt and an army and navy, Adams and Federalists had enacted a tax on houses, land and slaves, affecting every property owner in the country. Worse, after a single instance of tax revolt (a mob having freed two tax evaders from prison), Adams ordered the U.S. Army into action to collect the taxes. While the army could find no one to fight, Democratic-Republicans seized on this action as another example of Federalist tyranny.

Jefferson had steadily gathered behind him a great mass of small farmers, shopkeepers and other workers which asserted themselves as Democratic-Republicans in the election of 1800. Jefferson enjoyed extraordinary favor because of his appeal to American idealism. In his inaugural address, the first such speech in the new capital of Washington, DC, he promised "a wise and frugal government" to preserve order among the inhabitants but would "leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry, and improvement"[1].

Jefferson encouraged agriculture and westward expansion, most notably by the Louisiana Purchase and subsequent Lewis and Clark Expedition. Believing America to be a haven for the oppressed, he reduced the residency requirement for naturalization back to five years again.

By the end of his second term, Jefferson and Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin had reduced the national debt to less than $560 million. This was accomplished by reducing the number of executive department employees and Army and Navy officers and enlisted men, and by otherwise curtailing government and military spending.

To protect its shipping interests overseas, the U.S. fought the First Barbary War (1801–1805) in North Africa. This was followed later by the Second Barbary War (1815).

Louisiana Purchase and the War of 1812

The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 gave Western farmers use of the important Mississippi River waterway, removed the French presence from the western border of the United States, and provided U.S. settlers with vast potential for expansion.

A few weeks afterwards, war broke out between Britain and Napoleonic France. The United States, dependent on European revenues from the export of agricultural goods, tried to export food and raw materials to both warring Great Powers and to profit from transporting goods between their home markets and Caribbean colonies. Both sides permitted this trade when it benefited them but opposed it when it did not.

Following the 1805 destruction of the French navy at the Battle of Trafalgar, Britain sought to impose a stranglehold over French overseas trade ties. Thus, in retaliation against U.S. trade practices, Britain imposed a loose blockade of the American coast.

Believing that Britain could not rely on other sources of food than the United States, Congress and President Jefferson suspended all U.S. trade with foreign nations in the Embargo Act of 1807, hoping to get the British to end their blockade of the American coast. The Embargo Act, however, devastated American agricultural exports and weakened American ports while Britain found other sources of food.

James Madison won the U.S. presidential election of 1808, largely on the strength of his abilities in foreign affairs at a time when Britain and France were both on the brink of war with the United States. He was quick to repeal the Embargo Act, refreshing American seaports.

In response to continued British interference with American shipping (including the practice of impressment of American sailors into the British Navy), and to British aid to American Indians in the Old Northwest, the Twelfth Congress—led by Southern and Western Jeffersonians—declared war on Britain in 1812. Westerners and Southerners were the most ardent supporters of the war, given their concerns about defending and expanding western settlements and to having access to world markets for their agricultural exports. New England Federalists opposed the war, and their reputation suffered in the aftermath of the war, causing the party to fade away.

The United States and Britain came to a draw in the war after bitter fighting that lasted until January 8, 1815. The Treaty of Ghent, officially ending the war, essentially resulted in the maintenance of the status quo ante bellum, but Britain's alliance with the Native Americans ended.

The Battle of New Orleans – which took place after the treaty was signed because of slow cross-Atlantic communication – was a victory for the United States; it gave the country a psychological boost and propelled one of its commanders, Andrew Jackson, to political popularity.

Era of Good Feelings and the Rise of Nationalism

Following the War of 1812, America began to assert a newfound sense of nationalism. America began to rally around national heroes such as Andrew Jackson and patriotic feelings emerged in such works as Francis Scott Key's poem The Star Spangled Banner. Under the direction of Chief Justice John Marshall, the Supreme Court issued a series of opinions reinforcing the role of the national government. These decisions included McCulloch v Maryland and Gibbons v Ogden; both of which reaffirmed the supremacy of the national government over the states. The signing of the Adams-Onis Treaty helped to settle the western border of the country through popular and peaceable means.

Sectionalism

Even as nationalism increased across the country, its effects were limited by a renewed sense of sectionalism. The New England states that had opposed the War of 1812 felt an increasing decline in political power with the demise of the Federalist Party. This loss was tempered with the arrival of a new industrial movement and increased demands for northern banking. The industrial revolution in the United States was advanced by the immigration of Samuel Slater from Great Britain and arrival of textile mills beginning in Lowell, Massachusetts. The Lowell Mill Girls were typical of this new outlook on industrialization. In the south, the invention of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney radically shaped the perception of slave labor. The export of southern cotton was now the predominant source of economic revenue in the south. The western states continued to thrive under the "frontier spirit." Individualism was prized as exemplified by Davey Crockett and James Fenimore Cooper's folk hero Natty Bumpo from The Leatherstocking Tales. Following the death of Tecumseh, Native Americans lacked the unity to stop white settlement. The Black Hawk War in Illinois and Indiana foreshadowed the coming conflict between the two cultures.

Single party politics

Domestically, the presidency of James Monroe (1817–1825) was termed the "Era of Good Feelings" because of the decline of partisan politics. In one sense, the term disguised a period of vigorous factional and regional conflict; on the other hand, the phrase acknowledged the political triumph of the Democratic-Republican Party over the Federalist Party, which collapsed as a national force. Instead the sectional interests in the Democratic-Republican Party began to struggle for control of the party's agenda. Over time, the party would become torn apart by sectional interests.

Monroe is probably best known for the Monroe Doctrine, which he delivered in his message to Congress on December 2, 1823. In it, he proclaimed the Americas should be free from future European colonization and free from European interference in sovereign countries' affairs. It further stated the United States' intention to stay neutral in wars between European powers and their colonies but to consider any new colonies or interference with independent countries in the Americas as hostile acts towards the United States.

The decline of the Federalists brought disarray to the system of choosing presidents and the end of the short "Era". During this time state legislatures could nominate candidates. In the presidential election of 1824, Tennessee and Pennsylvania chose Andrew Jackson, with South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun as his running mate. Kentucky selected Speaker of the House Henry Clay, Massachusetts selected Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and a congressional caucus chose Treasury Secretary William H. Crawford.

Return of factionalism and political parties

Personality and sectional allegiance played important roles in determining the outcome of the election. Adams won the electoral votes from New England and most of New York; Clay won Kentucky, Ohio and Missouri; Jackson won the Southeast, Illinois, Indiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, Maryland and New Jersey; and Crawford won Virginia, Georgia and Delaware. No candidate gained a majority in the Electoral College. According to the provisions of the Constitution, the election was decided by the House of Representatives, where Clay was the most influential figure. In return for Clay's support, which essentially won him the presidency, John Quincy Adams appointed Clay as secretary of state in what became known as The Corrupt Bargain.

During Adams' administration, new party alignments appeared. Adams' followers took the name of "National Republicans", later to be changed to "Whigs". Though he governed honestly and efficiently, Adams was not a popular president, and his administration was marked with frustrations. Adams failed in his effort to institute a national system of roads and canals as part of the American System economic plan. His years in office appeared to be one long campaign for re-election, and his coldly intellectual temperament did not win friends.

Andrew Jackson, by contrast, had enormous popular appeal, especially among his followers in the newly-named Democratic Party that emerged from the Democratic-Republican Party, with its roots dating back to presidents Jefferson, Madison and Monroe. In the election of 1828, Jackson defeated Adams by an overwhelming electoral majority.

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson, eponym of the era of Jacksonian democracy, was a founder of the Democratic Party. His two presidential administrations oversaw vast change in the American political, social, and economic landscape.

Jacksonian democracy

Jackson drew his support from the small farmers of the West, and the workers, artisans and small merchants of the East, who sought to use their vote to resist the rising commercial and manufacturing interests associated with the Industrial Revolution.

The election of 1828 was a significant benchmark in the trend toward broader voter participation. Vermont had universal male suffrage since its entry into the Union, and Tennessee permitted suffrage for the vast majority of taxpayers. New Jersey, Maryland and South Carolina all abolished property and tax-paying requirements between 1807 and 1810. States entering the Union after 1815 either had universal white male suffrage or a low taxpaying requirement. From 1815 to 1821, Connecticut, Massachusetts and New York abolished all property requirements. In 1824, members of the Electoral College were still selected by six state legislatures. By 1828, presidential electors were chosen by popular vote in every state but Delaware and South Carolina. Nothing dramatized this democratic sentiment more than the election of Andrew Jackson.

Trail of Tears

In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which authorized the President to negotiate treaties that exchanged Indian tribal lands in the eastern states for lands west of the Mississippi River. In 1834, a special Indian territory was established in what is now the eastern part of Oklahoma. In all, Native American tribes signed 94 treaties during Jackson's two terms, ceding thousands of square miles to the Federal government.

The Cherokees, whose lands in western North Carolina and Georgia had been guaranteed by treaty since 1791, faced expulsion from their territory when a faction of Cherokees signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835, obtaining money in exchange for their land. Despite protests from the elected Cherokee government and many white supporters, the Cherokees were forced to make the long and cruel trek to the Indian Territory in 1838. Many died of disease and privation in what became known as the "Trail of Tears".

Nullification Crisis

Toward the end of his first term in office, Jackson was forced to confront the state of South Carolina on the issue of the protective tariff. The protective tariff passed by Congress and signed into law by Jackson in 1832 was milder than that of 1828, but it further embittered many in the state. In response, several South Carolina citizens endorsed the "states rights" principle of "nullification", which was enunciated by John C. Calhoun, Jackson's Vice President until 1832, in his South Carolina Exposition and Protest (1828). South Carolina dealt with the tariff by adopting the Ordinance of Nullification, which declared both the Tariff of 1828 and the Tariff of 1832 null and void within state borders.

Nullification was only the most recent in a series of state challenges to the authority of the federal government. In response to South Carolina's threat, Jackson sent seven small naval vessels and a man-of-war to Charleston in November 1832. On December 10, he issued a resounding proclamation against the nullifiers. South Carolina, the President declared, stood on "the brink of insurrection and treason", and he appealed to the people of the state to reassert their allegiance to that Union for which their ancestors had fought.

Senator Henry Clay, though an advocate of protection and a political rival of Jackson, piloted a compromise measure through Congress. Clay's 1833 compromise tariff specified that all duties more than 20% of the value of the goods imported were to be reduced by easy stages, so that by 1842, the duties on all articles would reach the level of the moderate tariff of 1816.

The rest of the South declared South Carolina's course unwise and unconstitutional. Eventually, South Carolina rescinded its action. Jackson had committed the federal government to the principle of Union supremacy. South Carolina, however, had obtained many of the demands it sought and had demonstrated that a single state could force its will on Congress.

Banking

Even before the nullification issue had been settled, another controversy arose to challenge Jackson's leadership. It concerned the rechartering of the Second Bank of the United States. The First Bank of the United States had been established in 1791, under Alexander Hamilton's guidance and had been chartered for a 20-year period. After the Revolutionary War, the United States had a large war debt to France and others, and the banking system of the fledgling nation was in disarray, as state banks printed their own currency, and the plethora of different bank notes made commerce difficult. Hamilton's national bank had been chartered to solve the debt problem and to unify the nation under one currency. While it stabilized the currency and stimulated trade, it was resented by Westerners and workers who believed that it was granting special favors to a few powerful men. When its charter expired in 1811, it was not renewed[2].

For the next few years, the banking business was in the hands of State-Chartered banks, which issued currency in excessive amounts, creating great confusion and fueling inflation and concerns that state banks could not provide the country with a uniform currency. the absence of a national bank during the War of 1812 greatly hindered financial operations of the government; therefore a second Bank of the United States was created in 1816.

From its inception, the Second Bank was unpopular in the newer states and territories and with less prosperous people everywhere. Opponents claimed the bank possessed a virtual monopoly over the country's credit and currency, and reiterated that it represented the interests of the wealthy few. Jackson, elected as a popular champion against it, vetoed a bill to recharter the bank. In his message to Congress, he denounced monopoly and special privilege, saying that "our rich men have not been content with equal protection and equal benefits, but have besought us to make them richer by act of Congress"[3].

In the election campaign that followed, the bank question caused a fundamental division between the merchant, manufacturing and financial interests (generally creditors who favored tight money and high interest rates), and the laboring and agrarian sectors, who were often in debt to banks and therefore favored an increased money supply and lower interest rates. The outcome was an enthusiastic endorsement of "Jacksonism". Jackson saw his reelection in 1832 as a popular mandate to crush the bank irrevocably; he found a ready-made weapon in a provision of the bank's charter authorizing removal of public funds.

In September 1833 Jackson ordered that no more government money be deposited in the bank and that the money already in its custody be gradually withdrawn in the ordinary course of meeting the expenses of government. Carefully-selected state banks, stringently restricted, were provided as a substitute. For the next generation, the U.S. would get by on a relatively-unregulated state banking system. This banking system helped fuel westward expansion through cheap credit, but kept the nation vulnerable to periodic panics. It was not until the Civil War that the U.S. Federal government again chartered a national bank.

Jackson groomed Martin van Buren as his successor, and he was easily elected president in 1836. However, a few months into his administration, the country fell into a deep economic slump known as the Panic of 1837, caused in large part by excessive speculation. Banks failed and unemployment soared. Although the depression had its roots in Jackson's economic policies, van Buren was blamed for the disaster. In the 1840 presidential election, he was defeated by the Whig candidate William Henry Harrison. However, his presidency would prove a non-starter when he fell ill with pneumonia and died after only a month in office. John Tyler, his vice president, succeeded him. Tyler was not popular since he had not been elected to the presidency, and was widely referred to as "His Accidency". The Whigs expelled him, and he became a president without a party.

Age of Reform

Spurred on by the Second Great Awakening, Americans entered a period of rapid social change and experimentation. New social movements arose, as well as many new alternatives to traditional religious thought. This period of American history was marked by the destruction of some traditional roles of society and the erection of new social standards. One of the unique aspects of the Age of Reform was that it was heavily grounded in religion, in contrast to the anti-clericalism that characterized contemporary European reformers.

Changes in religion and belief

Revivalism spread, led by the charismatic Charles Grandison Finney, in upstate New York and the Old Northwest. At the Rochester Revival of 1830, for example, prominent citizens concerned with the city's poverty and absenteeism had invited Finney to the city. For six months the preacher and his wife, Lydia, converted or reconverted numerous locals with citywide prayer meetings.[4] The wave of religious revival contributed to tremendous growth of the Methodist, Baptist and other denominations.[5]

As the Second Great Awakening challenged the traditional beliefs of the Calvinist faith, the movement inspired other groups to call into question their views on religion and society. One of the earliest movements was that of the Shakers in which members of a community held all of their possessions in "common" and lived in a prosperous, inventive, self-supporting society, with no sexual activity[6]. Many of these utopianist groups also believed in millennialism which prophesied the return of Christ and the beginning of a new age. The Harmony Society made three attempts to effect a millennial society with the most notable example at New Harmony, Indiana. Later, Scottish industrialist Robert Owen bought New Harmony and attempted to form a secular Utopian community there. Frenchman Charles Fourier began a similar secular experiment with his "phalanxes" that were spread across the Midwestern United States. However, none of these utopian communities lasted very long except for the Shakers.

The Shakers, founded by Mother Ann Lee,[7] peaked at around 6,000 in 1850 in communities from Maine to Kentucky. The Shakers condemned sexuality and demanded absolute celibacy. New members could only come from conversions, not children of current members. Shaker communities existed into the early 1900s and became noted for their furniture and handicrafts.[8].

Many of the more mainstream religious groups in the antebellum United States also took a negative view towards human sexuality, holding that it should be reserved strictly for procreation and that sex for pleasure would lead to weakness and loss of energy, and even insanity and death in some extreme cases.

The Perfectionist movement, led by John Humphrey Noyes, founded the utopian Oneida Community in 1848 with fifty-one devotees, in Oneida, New York. Noyes believed that the act of final conversion led to absolute and complete release from sin. Though their sexual practices were unorthodox, the community prospered because Noyes opted for modern manufacturing. Eventually abandoning religion to become a joint-stock company, Oneida thrived for many years and continues today as a silverware company.[9]

Joseph Smith also experienced a religious conversion in this era; under his guidance Mormon history began. Because of their unusual beliefs, which included recognition of the Book of Mormon as a supplement to the Bible, Mormons were rejected by mainstream Christians and forced to flee en masse from upstate New York to Nauvoo, Illinois, with the largest group ultimately continuing to the area around the Great Salt Lake, then part of Mexico. In 1848, the region fell under American control and later formed the Utah Territory, which was only admitted as a state in 1896 after the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints officially renounced polygamy.

For Americans wishing to bridge the gap between the earthly and spiritual worlds, spiritualism provided a means of communing with the dead. Spiritualists used mediums to communicate between the living and the dead through a variety of different means. The most famous mediums, the Fox sisters claimed a direct link to the spirit world, although it was later proven to be falsified. Spiritualism would gain a much larger following after the heavy number of casualties during the American Civil War with former First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln becoming an outspoken proponent.

Other groups seeking spiritual awaking gained popularity in the mid-1800s. Poet Ralph Waldo Emerson began the American transcendentalist movement in New England, to promote self-reliance and better understanding of the universe through contemplation of the over-soul. Transcendentalism was in essence an American offshoot of the Romantic movement in Europe. Among transcendentalists' core beliefs was an ideal spiritual state that "transcends" the physical, and is only realized through intuition rather than doctrine. Like many of the movements, the transcendentalists split over the idea of self-reliance. While Emerson and Henry David Thoreau promoted the idea of independent living, George Ripley brought transcendentalists together in a phalanx at Brook Farm to live cooperatively. Other authors such as Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe rejected transcendentalist beliefs.

So many of these new religious and spiritual groups began or concentrated within miles of each other in upstate New York that this area was nicknamed "the burned-over district" because there were so few people left who had not experienced a conversion.

Public schools movement

Education in the United States had long been a local affair with schools governed by locally elected school boards. As with much of the culture of the United States, education varied widely in the North and the South. In the New England states public education was common, although it was often class-based with the working class receiving little benefits. Instruction and curriculum were all locally determined and teachers were expected to meet rigorous demands of strict moral behavior. Schools taught religious values and applied Calvinist philosophies of discipline which included corporal punishment and public humiliation. In the South, there was very little organization of a public education system. Public schools were very rare and most education took place in the home with the family acting as instructors. The wealthier planter families were able to bring in tutors for instruction in the classics but many yeoman farming families had little access to education outside of the family unit.

The reform movement in education began in Massachusetts when Horace Mann started the common school movement. Mann advocated a statewide curriculum and instituted financing of school through local property taxes. Mann also fought protracted battles against the Calvinist influence in discipline, preferring positive reinforcement to physical punishment. Most children learned to read and write and spell from Noah Webster's Blue Backed Speller and later the McGuffey Readers. The readings inculcated moral values as well as literacy. Most states tried to emulate Massachusetts, but New England retained its leadership position for another century. German immigrants brought in kindergartens and gymnasiums, while Yankee orators sponsored the Lyceum movement that provided popular education for hundreds of towns and small cities.

Asylum movement

The social conscience that was raised in the early 1800s helped to elevate the awareness of mental illness and its treatment. A leading advocate of reform for mental illness was Dorothea Dix, a Massachusetts woman who made an intensive study of the conditions that the mentally ill were kept in. Dix's report to the Massachusetts state legislature along with the development of the Kirkbride Plan helped to alleviate the miserable conditions for many of the mentally ill. Although these facilities often fell short of their intended purpose, reformers continued to follow Dix's advocacy and call for increased study and treatment of mental illness.

Women's rights and the "cult of domesticity"

Following the end of the American Revolution and the birth of the new republic, American women were able to gain a limited political voice in what is known as republican motherhood. Under this philosophy women, such as Abigail Adams, were seen as the protectors of liberty and republicanism. Mothers were charged with passing down these ideals to their children through instruction of patriotic thoughts and feelings. By the turn of the 19th century, the role of women had changed significantly. In what is known as the "cult of domesticity" or "cult of true womanhood" middle class women lost much of their political voice.

In the South, tradition still abounded with society women on the pedestal and dedicated to entertaining and hosting others. This phenomenon is reflected in the 1965 book, The Inevitable Guest, based on a collection of letters by friends and relatives in North and South Carolina to Miss Jemima Darby, a distant relative of the author.[10]

Under the doctrine of two spheres, women were to exist in the “domestic sphere” at home while their husbands operated in the “public sphere” of politics and business. Women took on the new role of “softening” their husbands and instructing their children in piety and not republican values, while men handled the business and financial affairs of the family. Some doctors of this period even went so far as to suggest that women should not get an education, lest they divert blood away from the uterus to the brain and produce weak children. The coverture laws of ensured that men would hold political power over their wives. By the mid-1800s women associated with the abolition movement began to question their legal status in the United States as well. Leaders such as Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton broke from the cult when they organized the Seneca Falls Convention to call for women's rights.

Some of the strongest advocates for abolition (see below) were women, both black and white, who saw the legal limits placed on them magnified in slavery. Angelia and Sarah Grimké were southern women who moved North to advocate against slavery. The American Anti-Slavery Society welcomed women. Garrison along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott were so appalled that women were not allowed to participate at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London that they called for a women's rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York. It was at this convention that Sojourner Truth became recognized as a leading spokesperson for both abolition and women's rights.

Abolition movements

White abolitionism

The slavery abolitionism movement among whites was based on a combination of evangelical principles of the Second Great Awakening, the desire for racial purity in the United States, and the concern in the Northern states over the growing economic power of the South. One of the first abolitionist movements in the United States was the American Colonization Society which established the colony of Liberia in Africa as a means to repatriate slaves out of white society. Other white abolitionists rejected the idea of repatriation to Africa. Evangelist Theodore Weld led abolitionist revivals that called for immediate emancipation of slaves. William Lloyd Garrison founded The Liberator, an anti-slavery newspaper, and the American Anti-Slavery Society to call for abolition. A controversial figure, Garrison often was the focus of public anger. His advocacy of women's rights and inclusion of women in the leadership of the Society caused a rift within the movement. Rejecting Garrison's idea that abolition and women's rights were connected Lewis Tappan broke with the Society and formed the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. Most abolitionists were not as extreme as Garrison, who vowed that "The Liberator" would not cease publication until slavery was abolished. The state of Georgia even went so far as to offer a bounty on his head.

White abolitionists did not always face agreeable communities in the North. Garrison was almost lynched in Boston while newspaper publisher Elijah Lovejoy was killed in Alton, Illinois. The anger over abolition even spilled over into Congress where a gag rule was instituted to prevent any discussion of slavery on the floor of either chamber. Most whites viewed African-Americans as an inferior race and had little taste for abolitionists, often assuming that all were like Garrison. African-Americans had little freedom even in states where slavery was not permitted, being shunned by whites, subjected to discriminatory laws, and often forced to compete with Irish immigrants for menial, low-wage jobs. In the South meanwhile, planters argued that slavery was necessary to operate their plantations profitably and that emancipated slaves would attempt to Africanize the country as they had done in Haiti.

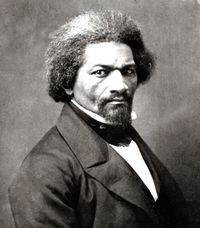

African American abolitionism

Both free-born African American citizens and former slaves took on leading roles in abolitionism as well. By far the most prominent spokesperson for abolition in the African American community was Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave whose eloquent condemnations of slavery drew both crowds of supporters as well as threats against his life. Douglass was a keen user of the printed word both through his newspaper The North Star and three best-selling autobiographies. For many white abolitionists, Douglass's views were too extreme and his interracial marriage went too far in pushing the boundaries of “acceptable” interaction between whites and African Americans.

Like the white abolition movement, African American advocates also differed in their message. David Walker published An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World calling for African American revolt against white tyranny. Other activists preferred to take action to assist the slaves in the American South. The Underground Railroad was established to help slaves out of the South through a series of trails and safe houses known as “stations.” Known as “conductors”, escaped slaves volunteered to return to the South to lead others to safety; former slaves, such as Harriet Tubman, risked their lives on these journeys.

Prohibition

Alcohol consumption was another target of reformers in the 1850s. Americans drank heavily, which contributed to violent behavior, crime, health problems, and poor workplace performance. Groups such as the American Temperance Society condemned liquor as being a scourge on society and urged temperance among their followers. The state of Maine attempted in 1851 to ban alcohol sales and production entirely, but it met resistance and was abandoned. The prohibition movement was forgotten during the Civil War, but would return afterwards.

Economic growth

In this period, the United States rapidly expanded economically from an agrarian nation into an industrial power. Industrialization in America involved two important developments. First, transportation was expanded. Second, improvements were made to industrial processes such as the use of interchangeable parts and railroads to ship goods more quickly. The government helped protect American manufacturers by passing a protective tariff.[12]

Westward expansion

After Napoleon's defeat and the Congress of Vienna in 1815, an exhausted Europe would enjoy more than three decades of peace. U.S. leaders paid less attention to European trade and more to the internal development in North America. With the end of the wartime British alliance with Native Americans east of the Mississippi River, white settlers were determined to colonize indigenous lands beyond the Mississippi. In the 1830s, the federal government forcibly deported the southeastern tribes to what is now Oklahoma. The "Trail of Tears", as the Cherokee called it, was performed at the instigation of Andrew Jackson. The Supreme Court ruled the deportation unconstitutional, but Jackson ignored this, allegedly saying "Now that you have proven, enforce."

Westward expansion by official acts of the U.S. Government was accompanied by the western (and northern in the case of New England) movement of settlers on and beyond the frontier. Daniel Boone was one frontiersman who pioneered the settlement of Kentucky. This pattern was followed throughout the West as American hunters and trappers traded with the Indians and explored the land. As skilled fighters and hunters, these Mountain Men trapped beaver in small groups throughout the Rocky Mountains. After the demise of the fur trade, they established trading posts throughout the west, continued trade with the Indians and served as guides and hunters for the western migration of settlers to Utah, Oregon and California.

Americans asserted a right to colonize vast expanses of North America beyond their country's borders, especially into Oregon, California, and Texas. By the mid-1840s, U.S. expansionism was articulated in the ideology of "Manifest Destiny". The Oregon Territory had been jointly administered by the US and Great Britain since 1819, but the two nations fell into disputes over the territory. President Polk ultimately convinced the British to sell everything south of the 49th parallel to the US except for Vancouver Island.

This would lead to open warfare. Mexico had gained its independence from Spain in 1821 and a few years later began inviting Americans to settle in Texas, a largely uninhabited region, under the condition that they adopt Mexican citizenship and convert to Roman Catholicism. This arrangement worked well until Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna became Mexico's president in 1830. He began stripping the Texan settlers of certain rights they had previously enjoyed. Slavery was also brought into the picture, as the Texans wanted to own slaves, which was illegal in Mexico. Eventually, the settlers revolted against Mexican rule. In 1835-1836, they fought a war with Mexico, capturing Santa Anna in battle and forcing him to sign a treaty recognizing Texas' independence. He agreed, but the Mexican Congress declared that any agreement made under duress (the Texans threatened to lynch Santa Anna if he didn't comply) was null and void.

Texas existed as an independent state for the next nine years and was largely left unmolested by Mexico, which still refused to recognize its independence. Most Texans wanted annexation to the United States, although a few advocated continued independence and expansion to the Pacific Ocean. However, the US had 13 free and 13 slave states and was unwilling to upset that balance by admitting another one. Finally, Mexico stated that annexation of Texas would be considered an act of war. On March 3, 1845, President Tyler authorized the annexation before leaving office the next day to be succeeded by James Polk.

In May 1846, Congress declared war on Mexico after a border incident. Troops under the command of Zachary Taylor defeated Santa Anna's army in northern Mexico while other American troops took possession of New Mexico and California. Mexico continued to resist despite a chaotic political situation, and so it was decided to launch an invasion of the country's heartland. An army led by Winfield Scott occupied the port of Veracruz, and pressed inland amid bloody fighting. Santa Anna offered to cede Texas and California north of Monterrey Bay, but negotiations broke down and the fighting resumed. In September 1847, Scott's army captured Mexico City. Santa Anna was forced to flee and a provisional government began the task of negotiating peace. Meanwhile, President Polk was in an embattled situation, faced both with opposition to the war and extremists who wanted either to annex the northern states of Mexico or even the entire country. Polk rejected the idea of taking anything south of the Rio Grande. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed on February 2, 1848. It recognized the Rio Grande as the southern boundary of Texas and ceded what is now the states of California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico to the United States, while also paying Mexico $15,000,000 for the territory. Over the next thirteen years, the territories ceded by Mexico became the focal point of sectional tensions over the expansion of slavery. The war had been highly controversial and was opposed by many in the US (including then-Representative Abraham Lincoln) who considered it a European-style war of conquest and imperialism. An exhausted James Polk left office in 1849 at the completion of his term and died a few months later. During the presidential election of 1848, Zachary Taylor ran as a Whig and won easily, even though he was an apolitical man who never voted in his life.

With Texas and Florida having been admitted to the union as slave states in 1845, California was made a free state in 1850.

Major events in the western movement of the U.S. population were the Homestead Act, a law by which, for a nominal price, a settler was given title to 160 acres (65 ha) of land to farm; the opening of the Oregon Territory to settlement; the Texas Revolution; the opening of the Oregon Trail; the Mormon Emigration to Utah in 1846–47; the California Gold Rush of 1849; the Colorado Gold Rush of 1859; and the completion of the nation's First Transcontinental Railroad on May 10, 1869.

1790 |

1800 |

1820 |

See also

- History of the United States (1849–1865)

- Origins of the American Civil War

- History of citizenship in the United States

References

- Notes

- ↑ LaGreca, Gen. Happy Birthday, Thomas Jefferson. Front Page Magazine: April 13, 2007

- ↑ Edward S. Kaplan, The Bank of the United States and the American Economy (1999)

- ↑ Bray Hammond, Banks and Politics in America from the Revolution to the Civil War (1967)p. 406

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gary B., Nash (2004 [reprinted 2009]). The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society, Volume 1 (to 1877) (6th ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall (London: Pearson; plus Longman and Vango imprints). ISBN 978-0-205-64282-3.

- ↑ "The Second Great Awakening". U-S-History.com. http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1091.html. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ↑ Stephen J. Stein, The Shaker Experience in America: A History of the United Society of Believers (1994)

- ↑ Hampson, Thomas (1996). "The Shakers". PBS.org. Crystal City, VA: Public Broadcasting Service. "I Hear American Singing – Profiles: Artists, Movements, Ideas" section. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/ihas/icon/shakers.html. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ↑ "The Shaker Religion". Essortment.com. Bellevue, WA: PageWise Inc.. 2002. http://www.essortment.com/all/theshakersreli_rggy.htm. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ↑ Hillebrand, Randall (February 20, 2008). "The Shakers / Oneida Community (Part Two): The Oneida Community". New York History Net: For Historians and Students of New York History and Culture. Albany, NY: Institute for New York State Studies. http://www.nyhistory.com/central/oneida.htm. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ↑ "John Ardis Cawthon, The Inevitable Guest in The Alcalde (September 1965) University of Texas at Austin alumni news". Google Books.

- ↑ "Boston Manufacturing Company Collection". Women, Enterprise and Society: A Guide to Resources in the Business Manuscripts Collection at Baker Library. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School, Harvard U.. 2009 [copyright date]. http://www.library.hbs.edu/hc/wes/collections/labor/textiles/content/1001956083.html. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ↑ Kelly, Martin (October 30, 2009). "Overview of the Industrial Revolution: The United States and the Industrial Revolution in the 19th Century". AmericanHistory.About.com. New York, NY: NYTC. http://americanhistory.about.com/od/industrialrev/a/indrevoverview.htm. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- Further reading

Surveys:

- Appleby, Joyce. Inheriting the Revolution: the First Generation of Americans. 2000. Covers the period from 1790-1830 through the lives of those born after 1776.

- Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (Oxford History of the United States) (2007); Pulitzer prize excerpt and text search

- Wood, Gordon. Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 (Oxford History of the United States) (2009) excerpt and text search

- Cultural and Intellectual History

- Perry, Lewis. Intellectual Life in America

- Henry Steele Commager, The Empire of Reason: How Europe Imagined and America Realized the Enlightenment

Interpretations of the spirit of the age:

Henry Adams: History of the United States During the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison v 1 ch 1-5 on America in 1800

Henry Adams: History of the United States During the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison v 1 ch 1-5 on America in 1800- C. Edward Skeen, 1816: America Rising. 2004 surveys postwar America & sees a new nation being born'

- Perry Miller. The Life of the Mind in America: From the Revolution to The Civil War (1965)

- Vernon Parrington, Main Currents in American Thought (1927) online(Vol 2: the Romantic Revolution, 1800–1860)

- Sellers, Charles. The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America 1815-46

- Smith, Page. The Shaping of America: A People's History of the Young Republic (1980). popular

Studies:

- Steven Watts. The Republic Reborn: War and the Making of Liberal America, 1790-1820 (1987) (a richly documented study which offers dozens of case studies and snapshots of life in the early republic)

- Kastor, Peter J. The Nation's Crucible: The Louisiana Purchase and the Creation of America. 2004.

- Ratcliffe, D. J.: Party Spirit in a Frontier Republic: Democratic Politics in Ohio, 1793-1821 (1998)

- Richard Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. 2005. 'An excellent cultural history of New England and upstate New York, Ohio, Missouri, Illinois, as well as full biography of a most interesting American from 1805-1844'

From a legal perspective:

- Morton J. Horwitz. The Transformation of American Law, 1780-1860 (1977) (uses the evolution of the law, especially as seen in the decisions of state courts in the north, as a way of measuring intellectual and cultural changes in the whole society)

- James Willard Hurst, Law and the Conditions of Freedom in the Nineteenth Century United States (University of Wisconsin Press, 1956)

- Lawrence M. Friedman. A History of American Law, 2d Ed. (1985)

- G. Edward White (with Gerald Gunther). The Marshall Court and Cultural Change, 1815-1835 (Abr. Ed., 1990)

- R. Kent Newmyer, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story: Statesman of the Old Republic (1985).

Social history:

- Gaillard Hunt: As We Were: Life in America 1814 (1914(?), Republished In 1993 by Berkshire House Publishers, Originally Titled Life in America

- Jack Larkin: The Reshaping of Everyday Life, 1790-1840 (Harper & Row, 1988 )

- Daniel J. Boorstin, The Americans: the National Experience

External links

- Frontier History of the United States at Thayer's American History site

- A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns, 1787-1825

|

|||||||||||