Hepatocellular carcinoma

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

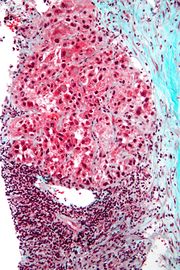

Hepatocellular carcinoma in an individual that was hepatitis C positive. Autopsy specimen. |

|

| ICD-10 | C22.0 |

| ICD-9 | 155 |

| ICD-O: | M8170/3 |

| MedlinePlus | 000280 |

| eMedicine | med/787 |

| MeSH | D006528 |

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC, also called malignant hepatoma) is a primary malignancy (cancer) of the liver. Most cases of HCC are secondary to either a viral hepatitide infection (hepatitis B or C) or cirrhosis (alcoholism being the most common cause of hepatic cirrhosis).[1] In countries where hepatitis is not endemic, most malignant cancers in the liver are not primary HCC but metastasis (spread) of cancer from elsewhere in the body, e.g., the colon. Treatment options of HCC and prognosis are dependent on many factors but especially on tumor size and staging. Tumor grade is also important. High-grade tumors will have a poor prognosis, while low-grade tumors may go unnoticed for many years, as is the case in many other organs, such as the breast, where a ductal carcinoma in situ (or a lobular carcinoma in situ) may be present without any clinical signs and without correlate on routine imaging tests, although in some occasions it may be detected on more specialized imaging studies like MR mammography.

The usual outcome is poor, because only 10 - 20% of hepatocellular carcinomas can be removed completely using surgery. If the cancer cannot be completely removed, the disease is usually deadly within 3 to 6 months.[2] This is partially due to late presentation with large tumours, but also the lack of medical expertise and facilities. This is a rare tumor in the United States. A new receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, sorafenib has been shown in a Spanish phase III clinical trial to add two months to the lifespan of late stage HCC patients with well preserved liver function [3].

Contents |

Risk factors

The main risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma are

When hepatocellular adenomas grow to a size of more than 6–8 cm, they are considered cancerous and thus become a risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. The use of birth control pills is one risk factor to develop an adenoma.

Diabetics are also at risk for adenomas. Also, those individuals who abuse anabolic steroids are also at risk to develop hepatic adenomas.[4]

Although hepatocellular carcinoma most commonly affects adults, children who are affected with biliary atresia, infantile cholestasis, glycogen-storage diseases, and other cirrhotic diseases of the liver are predisposed to developing hepatocellular carcinoma.

Children and adolescents are unlikely to have chronic liver disease, however, if they suffer from congenital liver disorders, this fact increases the chance of developing hepatocellular carcinoma.[5]

Signs and symptoms

HCC may present with jaundice, bloating from ascites, easy bruising from blood clotting abnormalities or as loss of appetite, unintentional weight loss, abdominal pain,especially in the upper -right part, nausea, emesis, or fatigue.[6]

Pathogenesis

Hepatocellular carcinoma, like any other cancer, develops when there is a mutation to the cellular machinery that causes the cell to replicate at a higher rate and/or results in the cell avoiding apoptosis. In particular, chronic infections of hepatitis B and/or C can aid the development of hepatocellular carcinoma by repeatedly causing the body's own immune system to attack the liver cells, some of which are infected by the virus, others merely bystanders. While this constant cycle of damage followed by repair can lead to mistakes during repair which in turn lead to carcinogenesis, this hypothesis is more applicable, at present, to hepatitis C. Chronic hepatitis C causes HCC through the stage of cirrhosis. In chronic hepatitis B, however, the integration of the viral genome into infected cells can directly induce a non-cirrhotic liver to develop HCC. Alternatively, repeated consumption of large amounts of ethanol can have a similar effect. Besides, cirrhosis is commonly caused by alcoholism, chronic hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C. The toxin aflatoxin from certain Aspergillus species of fungus is a carcinogen and aids carcinogenesis of hepatocellular cancer by building up in the liver. The combined high prevalence of rates of aflatoxin and hepatitis B in settings like China and West Africa has led to relatively high rates of heptatocellular carcinoma in these regions. Other viral hepatitides such as hepatitis A have no potential to become a chronic infection and thus are not related to hepatocellular carcinoma.

Diagnosis

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) most commonly appears in a patient with chronic viral hepatitis (hepatitis B or hepatitis C, 20%) or with cirrhosis (about 80%). These patients commonly undergo surveillance with ultrasound due to the cost-effectiveness.

In patients with a higher suspicion of HCC (such as rising alpha-fetoprotein and des-gamma carboxyprothrombin levels), the best method of diagnosis involves a CT scan of the abdomen using intravenous contrast agent and three-phase scanning (before contrast administration, immediately after contrast administration, and again after a delay) to increase the ability of the radiologist to detect small or subtle tumors. It is important to optimize the parameters of the CT examination, because the underlying liver disease that most HCC patients have can make the findings more difficult to appreciate.

On CT, HCC can have three distinct patterns of growth:

- A single large tumor

- Multiple tumors

- Poorly defined tumor with an infiltrative growth pattern

A biopsy is not needed to confirm the diagnosis of HCC if certain imaging criteria are met.

The key characteristics on CT are hypervascularity in the arterial phase scans, washout or de-enhancement in the portal and delayed phase studies, a pseudocapsule and a mosaic pattern. Both calcifications and intralesional fat may be appreciated.

CT scans use contrast agents, which are typically iodine or barium based. Some patients are allergic to one or both of these contrast agents, most often iodine. Usually the allergic reaction is manageable and not life threatening.

An alternative to a CT imaging study would be the MRI. MRI's are more expensive and not as available because fewer facilities have MRI machines. More important MRI are just beginning to be used in tumor detection and fewer radiologists are skilled at finding tumors with MRI studies when it is used as a screening device. Mostly the radiologists are using MRIs to do a secondary study to look at an area where a tumor has already been detected. MRI's also use contrast agents. One of the best for showing details of liver tumors is very new: iron oxide nano-particles appears to give better results. The latter are absorbed by normal liver tissue, but not tumors or scar tissue.

In a review article of the screening, diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma, 4 articles were selected for comparing the accuracy of CT and MRI in diagnosing this malignancy.[7] Radiographic diagnosis was verified against post-transplantation biopsy as the gold standard. With the exception of one instance of specificity, it was discovered that MRI was more sensitive and specific than CT in all four studies.

Pathology

Macroscopically, liver cancer appears as a nodular or infiltrative tumor. The nodular type may be solitary (large mass) or multiple (when developed as a complication of cirrhosis). Tumor nodules are round to oval, grey or green (if the tumor produces bile), well circumscribed but not encapsulated. The diffuse type is poorly circumscribed and infiltrates the portal veins, or the hepatic veins (rarely).

Microscopically, there are four architectural and cytological types (patterns) of hepatocellular carcinoma: fibrolamellar, pseudoglandular (adenoid), pleomorphic (giant cell) and clear cell. In well differentiated forms, tumor cells resemble hepatocytes, form trabeculae, cords and nests, and may contain bile pigment in cytoplasm. In poorly differentiated forms, malignant epithelial cells are discohesive, pleomorphic, anaplastic, giant. The tumor has a scant stroma and central necrosis because of the poor vascularization.[8]

Staging

Important features that guide treatment include: -

- size

- spread (stage)

- involvement of liver vessels

- presence of a tumor capsule

- presence of extrahepatic metastases

- presence of daughter nodules

- vascularity of the tumor

MRI is the best imaging method to detect the presence of a tumor capsule.

Management

- Surgical resection to remove a tumor together with surrounding liver tissue while preserving enough liver remnant for normal body function. This treatment offers the best prognosis for long-term survival, but unfortunately only 10-15% of patients are suitable for surgical resection. This is often due to extensive disease or poor liver function. Resection in cirrhotic patients carries high morbidity and mortality. The expected liver remnant should be more than 25% of the total size for a non-cirrhotic liver, while that should be more than 40% of the total size for a cirrhotic liver. The overall recurrent rate after resection is 50-60%.

- Liver transplantation to replace the diseased liver with a cadaveric liver or a living donor graft. Historically low survival rates (20%-36%). Recent improvement (61.1%; 1996–2001), likely related to adoption of the Milan criteria at US transplantation centers. If the liver tumor has metastasized, the immuno-suppressant post-transplant drugs decrease the chance of survival.

- Percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) well tolerated, high RR in small (<3 cm) solitary tumors; as of 2005, no randomized trial comparing resection to percutaneous treatments; recurrence rates similar to those for postresection.

- Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) is usually performed for unresectable tumors or as a temporary treatment while waiting for liver transplant. TACE is done by injecting an antineoplastic drug (e.g. cisplatin) mixed with a radioopaque contrast (e.g. Lipiodol) and an embolic agent (e.g. Gelfoam) into the right or left hepatic artery via the groin artery. As of 2005, multiple trials show objective tumor responses and slowed tumor progression but questionable survival benefit compared to supportive care; greatest benefit seen in patients with preserved liver function, absence of vascular invasion, and smallest tumors. TACE is not suitable for big tumors (>8 cm), presence of portal vein thrombus, tumors with portal-systemic shunt and patients with poor liver function.

- Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) uses high frequency radio-waves to destroy tumor by local heating. The electrodes are inserted into the liver tumor under ultrasound image guidance using percutaneous, laparoscopic or open surgical approach. It is suitable for small tumors (<5 cm). A large randomised trial comparing surgical resection and RFA for small HCC showed similar 4 years-survival and less morbidities for patients treated with RFA.[9]

- Selective internal radiation therapy can be used to destroy the tumor from within (thus minimizing exposure to healthy tissue). There are currently two products available, SIR-Spheres and TheraSphere The latter is an FDA approved treatment for primary liver cancer (HCC) which has been shown in clinical trials to increase survival rate of low-risk patients. SIR-Spheres are FDA approved for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer but outside the US SIR-Spheres are approved for the treatment of any non-resectable liver cancer including primary liver cancer. This method uses a catheter (inserted by a radiologist) to deposit radioactive particles to the area of interest.

- Intra-arterial iodine-131–lipiodol administration Efficacy demonstrated in unresectable patients, those with portal vein thrombus. This treatment is also used as adjuvant therapy in resected patients (Lau at et, 1999). It is believed to raise the 3-year survival rate from 46 to 86%. This adjuvant therapy is in phase III clinical trials in Singapore and is available as a standard medical treatment to qualified patients in Hong Kong.

- Combined PEI and TACE can be used for tumors larger than 4 cm in diameter, although some Italian groups have had success with larger tumours using TACE alone.

- High intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) (not to be confused with normal diagnostic ultrasound) is a new technique which uses much more powerful ultrasound to treat the tumour. Still at a very experimental stage. Most of the work has been done in China. Some early work is being done in Oxford and London in the UK.

- Hormonal therapy Antiestrogen therapy with tamoxifen studied in several trials, mixed results across studies, but generally considered ineffective Octreotide (somatostatin analogue) showed 13-month MS v 4-month MS in untreated patients in a small randomized study; results not reproduced.

- Adjuvant chemotherapy: No randomized trials showing benefit of neoadjuvant or adjuvant systemic therapy in HCC; single trial showed decrease in new tumors in patients receiving oral synthetic retinoid for 12 months after resection/ablation; results not reproduced. Clinical trials have varying results.[10]

- Palliative: Regimens that included doxorubicin, cisplatin, fluorouracil, interferon, epirubicin, or taxol, as single agents or in combination, have not shown any survival benefit (RR, 0%-25%); a few isolated major responses allowed patients to undergo partial hepatectomy; no published results from any randomized trial of systemic chemotherapy.

- Cryosurgery: Cryosurgery is a new technique that can destroy tumors in a variety of sites (brain, breast, kidney, prostate, liver). Cryosurgery is the destruction of abnormal tissue using sub-zero temperatures. The tumor is not removed and the destroyed cancer is left to be reabsorbed by the body. Initial results in properly selected patients with unresectable liver tumors are equivalent to those of resection. Cryosurgery involves the placement of a stainless steel probe into the center of the tumor. Liquid nitrogen is circulated through the end of this device. The tumor and a half inch margin of normal liver are frozen to -190°C for 15 minutes, which is lethal to all tissues. The area is thawed for 10 minutes and then re-frozen to -190°C for another 15 minutes. After the tumor has thawed, the probe is removed, bleeding is controlled, and the procedure is complete. The patient will spend the first post-operative night in the intensive care unit and typically is discharged in 3 – 5 days. Proper selection of patients and attention to detail in performing the cryosurgical procedure are mandatory in order to achieve good results and outcomes. Frequently, cryosurgery is used in conjunction with liver resection as some of the tumors are removed while others are treated with cryosurgery. Patients may also have insertion of a hepatic intra-arterial artery catheter for post-operative chemotherapy. As with liver resection, the surgeon should have experience with cryosurgical techniques in order to provide the best treatment possible.

There is a new drug Sorafenib which was originally used for Renal Cell Cancer that has shown promising results when used with Hepatocellular Cancer

- Interventional radiology

- Agaricus blazei mushrooms inhibited abnormal collagen fiber formation in human hepatocarcinoma cells in an in vitro experiment.[11]

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; TACE, transarterial embolization/chemoembolization; PFS, progression-free survival; PS, performance status; HBV, hepatitis B virus; PEI, percutaneous ethanol injection; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; RR, response rate; MS, median survival.

A systematic review assessed 12 articles involving a total of 318 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with Yttrium-90 radioembolization.[12] Excluding a study of only one patient, post-treatment CT evaluation of the tumor showed a response ranging from 29 to 100 % of patients evaluated, with all but two studies showing a response of 71 % or greater.

A group of researchers studied the use of Sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Sorafenib is a small molecule that inhibits tumor-cell proliferation and tumor angionesis. It also increases the rate of apoptosis in other tumor models. The results indicated that single-agent sorafenib might have a beneficial therapeutic effect. In this study, for instance, the median overall survival was of 9.2 months and the median time to progression was of 5.5 months. Also, the survival benefit represented a 31% relative reduction in the risk of death.[13]

Prevention

Since hepatitis B or C is one of the main causes of hepatocellular carcinoma, prevention of this infection is key to then prevent hepatocellular carcinoma. Thus, childhood vaccination against hepatitis B may reduce the risk of liver cancer in the future.[14]

In the case of patients with cirrhosis, alcohol consumption is to be avoided. Also, screening for hemochromatosis may be beneficial for some patients.[15]

Prognosis

The usual outcome is poor, because only 10 - 20% of hepatocellular carcinomas can be removed completely using surgery. If the cancer cannot be completely removed, the disease is usually fatal within 3 – 6 months. However, survival can vary, and occasionally people will survive much longer than 6 months. The prognosis for metastatic or unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma has recently improved due to the approval of nexavar for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma.

Epidemiology

HCC is one of the most common tumors worldwide. The epidemiology of HCC exhibits two main patterns, one in North America and Western Europe and another in non-Western countries, such as those in sub-Saharan Africa, central and Southeast Asia, and the Amazon basin. Males are affected more than females usually and it is most common between the age of 30 to 50[1] Hepatocellular carcinoma causes 662,000 deaths worldwide per year[17], about half of them in China.

Non-Western Countries

In some parts of the world, such as sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, HCC is the most common cancer, generally affecting men more than women, and with an age of onset between late teens and 30s. This variability is in part due to the different patterns of hepatitis B and hepatitis C transmission in different populations - infection at or around birth predispose to earlier cancers than if people are infected later. The time between hepatitis B infection and development into HCC can be years, even decades, but from diagnosis of HCC to death the average survival period is only 5.9 months according to one Chinese study during the 1970-80s, or 3 months (median survival time) in Sub-Saharan Africa according to Manson's textbook of tropical diseases. HCC is one of the deadliest cancers in China where chronic hepatitis B is found in 90% of cases. In Japan, chronic hepatitis C is associated with 90% of HCC cases. Food infected with Aspergillus flavus (especially peanuts and corns stored during prolonged wet seasons) which produces aflatoxin poses another risk factor for HCC.

North America and Western Europe

Most malignant tumors of the liver discovered in Western patients are metastases (spread) from tumors elsewhere.[1] In the West, HCC is generally seen as a rare cancer, normally of those with pre-existing liver disease. It is often detected by ultrasound screening, and so can be discovered by health-care facilities much earlier than in developing regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa.

Acute and chronic hepatic porphyrias (acute intermittent porphyria, porphyria cutanea tarda, hereditary coproporphyria, variegate porphyria) and tyrosinemia type I are risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma. The diagnosis of an acute hepatic porphyria (AIP, HCP, VP) should be sought in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma without typical risk factors of hepatitis B or C, alcoholic liver cirrhosis or hemochromatosis. Both active and latent genetic carriers of acute hepatic porphyrias are at risk for this cancer, although latent genetic carriers have developed the cancer at a later age than those with classic symptoms. Patients with acute hepatic porphyrias should be monitored for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Society and culture

Awareness

The Jade Ribbon Campaign is used for awareness of liver cancer and hepatitis B in the Pacific Islands, where such illnesses are more widespread than elsewhere.

Famous people

- Johannes Brahms famous late Romantic German composer. Died April 3, 1897 of liver cancer.

- Morihei Ueshiba founder of the Japanese martial art of aikido. Died in 1969 of hepatocellular carcinoma.

- John Coltrane Jazz musician. Died in 1967 from liver cancer.

- Jim Hutton Died in 1979 from liver cancer.

- Mickey Mantle Hall of Fame Baseball player with the New York Yankees.

- Chris LeDoux Country Music Hall of Fame legend, and former Pro Rodeo rider.

- Munetaka Higuchi Drummer for Japanese Heavy Metal band Loudness, Died in 2008 of hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Mick Ronson British Rock'n'Roll guitarist who died in 1993 of hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Erich Honecker former leader of East Germany who died in 1994 in exile.

- Ray Charles famous recording soulful music artist, Rock And Roll Hall of Fame, died on June 10, 2004.

- Sun Yat-sen Father of the Nation in mainland China and in Taiwan

- Édith Piaf French singer and cultural icon who "is almost universally regarded as France's greatest popular singer."

- Gregory Hines Professional dancer, film actor, and choreographer. Died in August 2003 of liver cancer.

- Dave Thomas Founder of Wendys, died in 2002 of liver cancer.

Research

Current research includes the search for the genes that are disregulated in HCC,[18] protein markers,[19] and other predictive biomarkers.[20][21] As similar research is yielding results in various other malignant diseases, it is hoped that identifying the aberrant genes and the resultant proteins could lead to the identification of pharmacological interventions for HCC.[22]

Gallery

.jpg) |

_at_higher_magnification.jpg) |

See also

- Hemihypertrophy

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Kumar V, Fausto N, Abbas A (editors) (2003). Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (7th ed.). Saunders. pp. 914–7. ISBN 978-0-721-60187-8.

- ↑ Hepatocellular carcinoma MedlinePlus, Medical Encyclopedia

- ↑ http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/359/4/378

- ↑ "Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Diseases". http://www.hepatocellular.org/. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Pathophysiology". http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/986988-overview. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/liver-cancer/DS00399/DSECTION=symptoms

- ↑ El-Serag HB, Marrero JA, Rudolph L, Reddy KR (May 2008). "Diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma". Gastroenterology 134 (6): 1752–63. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.090. PMID 18471552. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0016-5085(08)00426-5.

- ↑ Hepatocellular carcinoma (Photo) ATLAS OF PATHOLOGY

- ↑ Chen, Min-Shan; Li, Jin-Qing; Zheng, Yun; Guo, Rong-Ping; Liang, Hui-Hong; Zhang, Ya-Qi; Lin, Xiao-Jun; Lau, Wan Y (2006). "A Prospective Randomized Trial Comparing Percutaneous Local Ablative Therapy and Partial Hepatectomy for Small Hepatocellular Carcinoma". Annals of Surgery 243 (3): 321–8. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000201480.65519.b8.

- ↑ American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2005 Annual Meeting, Abstracts on Hepatobiliary Cancer

- ↑ Sorimachi, K (2008), "Inhibitory effect of Agaricus blazei Murill components on abnormal collagen fiber formation in human hepatocarcinoma cells", Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 72: 621–3, doi:10.1271/bbb.70700

- ↑ Vente MA, Wondergem M, van der Tweel I, et al (April 2009). "Yttrium-90 microsphere radioembolization for the treatment of liver malignancies: a structured meta-analysis". Eur Radiol 19 (4): 951–9. doi:10.1007/s00330-008-1211-7. PMID 18989675.

- ↑ "Sorafenib in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma". http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/359/4/378. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Hepatocellular carcinoma". https://health.google.com/health/ref/Hepatocellular+carcinoma. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Prevention". http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000280.htm. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ↑ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_country/en/index.html. Retrieved Nov. 11, 2009.

- ↑ "Cancer". World Health Organization. February 2006. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- ↑ Genetic research in HCC Stanford Asian Liver Center

- ↑ Huntington Medical Research Institute News, May 2005

- ↑ Journal of Clinical Oncology, Special Issue on Molecular Oncology: Receptor-Based Therapy, April 2005

- ↑ Lau W, Leung T, Ho S, Chan M, Machin D, Lau J, Chan A, Yeo W, Mok T, Yu S, Leung N, Johnson P (1999). "Adjuvant intra-arterial iodine-131-labelled lipiodol for resectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective randomised trial". Lancet 353 (9155): 797–801. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06475-7. PMID 10459961.

- ↑ Thomas M, Zhu A (2005). "Hepatocellular carcinoma: the need for progress". J Clin Oncol 23 (13): 2892–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.03.196. PMID 15860847. http://www.jco.org/cgi/content/full/23/13/2892.

External links

- NCI Liver Cancer Homepage

- Blue Faery: The Adrienne Wilson Liver Cancer Association

- Liver cancer overview from Mayo Clinic

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||