Hemorrhoid

| Hemorrhoids | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

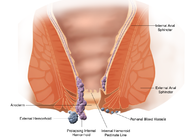

Schematic demonstrating the anatomy of hemorrhoids. |

|

| ICD-10 | I84. |

| ICD-9 | 455 |

| DiseasesDB | 10036 |

| MedlinePlus | 000292 |

| eMedicine | med/2821 emerg/242 |

| MeSH | D006484 |

Hemorrhoids are normal vascular structures in the anal canal which help with stool control.[1][2] They become pathological or known as piles[3] when swollen or inflamed. In their physiological state they act as cushions composed of arterio-venous channels and connective tissue that aid the passage of stool. The symptoms of pathological hemorrhoids depend on the type present. Internal hemorrhoids usually present with painless rectal bleeding while external hemorrhoids present with pain in the area of the anus.

Recommended treatment consists of increasing fiber intake, oral fluids to maintain hydration, NSAID analgesics, sitz baths, and rest. Surgery is reserved for those who fail to improve following these measures.

Contents |

Classification

There are two types of hemorrhoids external and internal which are differentiated via their position with respect to the dentate line.[3]

External

External hemorrhoids are those that occur outside the anal verge (the distal end of the anal canal). Specifically they are varicosities of the veins draining the territory of the inferior rectal arteries, which are branches of the internal pudendal artery. They are sometimes painful, and often accompanied by swelling and irritation. Itching, although often thought to be a symptom of external hemorrhoids, is more commonly due to skin irritation. External hemorrhoids are prone to thrombosis: if the vein ruptures and/or a blood clot develops, the hemorrhoid becomes a thrombosed hemorrhoid.[4]

Internal

Internal hemorrhoids are those that occur inside the rectum. Specifically they are varicosities of veins draining the territory of branches of the superior rectal arteries. As this area lacks pain receptors, internal hemorrhoids are usually not painful and most people are not aware that they have them. Internal hemorrhoids, however, may bleed when irritated. Untreated internal hemorrhoids can lead to two severe forms of hemorrhoids: prolapsed and strangulated hemorrhoids. Prolapsed hemorrhoids are internal hemorrhoids that are so distended that they are pushed outside the anus. If the anal sphincter muscle goes into spasm and traps a prolapsed hemorrhoid outside the anal opening, the supply of blood is cut off, and the hemorrhoid becomes a strangulated hemorrhoid.

Internal hemorrhoids can be further graded by the degree of prolapse.[3][5]

- Grade I: No prolapse.

- Grade II: Prolapse upon defecation but spontaneously reduce.

- Grade III: Prolapse upon defecation, but must be manually reduced.

- Grade IV: Prolapsed and cannot be manually reduced.

Signs and symptoms

Hemorroids usually present with itching, rectal pain, or rectal bleeding.[2] In most cases, symptoms will resolve within a few days. External hemorrhoids are painful while internal hemorrhoids usually are not unless they become thrombosed or necrotic.[3][2]

The most common symptom of internal hemorrhoids is bright red blood covering the stool, a condition known as hematochezia, on toilet paper, or in the toilet bowl.[2] They may protrude through the anus. Symptoms of external hemorrhoids include painful swelling or lump around the anus.

Causes

A number of factors may lead to the formations of hemorrhoids including irregular bowel habits (constipation or diarrhea), exercise, nutrition (low-fiber diet), increased intra-abdominal pressure (prolonged straining), pregnancy, genetics, absence of valves within the hemorrhoidal veins, and aging.[3]

Other factors that can increase the rectal vein pressure resulting in hemorrhoids include obesity, and sitting for long periods of time.[6]

During pregnancy, pressure from the fetus on the abdomen and hormonal changes cause the hemorrhoidal vessels to enlarge. Delivery also leads to increase intra abdominal pressures.[7][8] Surgical treatment is rarely needed as symptoms usually resolve post delivery.[3]

Pathophysiology

Hemorrhoid cushions are a part of normal human anatomy and only become a pathological disease when they experience abnormal changes. There are three cushions present in the normal anal canal.[3]

They are important for continence contributing to at rest 15%-20% of anal closure pressure and act to protect the anal sphincter muscles during the passage of stool.[2]

Prevention

The best way to prevent hemorrhoids is to keep stools soft so they pass easily, thus decreasing pressure and straining, and to empty bowels as soon as possible after the urge occurs. Exercise, including walking, and increased fiber in the diet help reduce constipation and straining by producing stools that are softer and easier to pass.[9] Spending less time attempting to defecate and avoiding reading while on the toilet have been recommended.[3]

Diagnosis

A visual examination of the anus and surrounding area may be able to diagnose external or prolapsed hemorrhoids. A rectal exam may be performed to detect possible rectal tumors, polyps, an enlarged prostate, or abscesses. This examination may not be possible without appropriate sedation due to pain.[3]

Visual confirmation of internal hemorrhoids is via anoscopy. This device is basically a hollow tube with a light attached at one end that allows one to see the internal hemorrhoids, as well possible polyps in the rectum.

|

Classical appearance of an external hemorrhoid. |

Direct view of a hemorrhoid as seen by sigmoidoscopy |

Endoscopic image of internal hemorrhoids seen on retroflexion of the flexible sigmoidoscope at the ano-rectal junction. |

Differential

Many anorectal problems, including fissures, fistulae, abscesses, colorectal cancer, rectal varices and itching have similar symptoms and may be incorrectly referred to as hemorrhoids.[3]

Treatments

Conservative treatment typically consists of increasing dietary fiber, oral fluids to maintain hydration, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID)s, sitz baths, and rest.[3] Increased fiber intake has been shown to improve outcomes[10] and may be achieved by dietary alterations or the consumption of fibre supplements.[3][11]

While many topical agents and suppositories are available for the treatment of hemorrhoids there is little evidence to support their use.[3] Preparation H may improve local symptoms but does not improve the underlying disorder and long term use is discouraged due to local irritation of the skin.[3]

Procedures

- Rubber band ligation is a procedure in which elastic bands are applied onto an internal hemorrhoid at least 1 cm above the dentate line to cut off its blood supply.[3] Within 5–7 days, the withered hemorrhoid falls off.[3] If the band is placed too close to the dentate line intense pain results immediately afterwards.[3] Cure rate has been found to be about 87%.[3]

- Sclerotherapy involves the injection of a sclerosing agent (such as phenol) into the hemorrhoid. This causes the vein walls to collapse and the hemorrhoids to shrivel up. The success rate at four years is 70%.[3]

- A number of cautery methods have been shown to be effective for hemorrhoids. This can be done using electrocautery, infrared radiation,[3] or cryosurgery.[12]

A number of surgical techniques may be used if conservative medical management fails. All are associated with some degree of complications including urinary retention, due to the close proximity to the rectum of the nerves that supply the bladder, bleeding, infection, and anal strictures.[3]

- Hemorrhoidectomy is a surgical excision of the hemorrhoid used primary only in severe cases.[3] It is associated with significant post operative pain and usually requires 2–4 weeks for recovery.[3]

- Doppler guided transanal hemorrhoidal dearterialization is a minimally invasive treatment using an ultrasound doppler to accurately locate the arterial blood inflow. These arteries are then “tied off” and the prolapsed tissue is sutured back to its normal position. It has a slightly higher recurrence rate however has less complications compared to a hemorrhoidectomy.[3]

- Stapled hemorrhoidectomy is a procedure that involves resection of soft tissue proximal to the dentate line, disrupting the blood flow to the hemorrhoids. It is generally less painful than complete removal of hemorrhoids and was associated with faster healing compare to a hemorrhoidectomy.[3]

Prognosis

Hemorrhoids are usually benign.

Epidemiology

Symptomatic hemorrhoids affect at least 50% of the American population at some time during their lives, with around 5% of the population suffering at any given time, and both sexes experiencing the same incidence of the condition.[3][13] They are more common in Caucasians.[14]

Etymology

First attested in English 1398, the word hemmorrhoid derives from the Old French "emorroides", from Latin "hæmorrhoida -ae",[15] in turn from the Greek "αἱμορροΐς" (haimorrhois), "liable to discharge blood", from "αἷμα" (haima), "blood"[16] + "ῥόος" {rhoos), "stream, flow, current",[17] itself from "ῥέω" (rheo), "to flow, to stream".[18]

Notable cases

- Hall-of-Fame baseball player George Brett was famously removed from a game in the 1980 World Series due to hemorrhoid pain. After undergoing minor surgery, Brett returned to play in the next game, quipping "...my problems are all behind me."[19] Brett underwent further hemorrhoid surgery the following spring.[20]

References

- ↑ Chen, Herbert (2010). Illustrative Handbook of General Surgery. Berlin: Springer. pp. 217. ISBN 1-84882-088-7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Schubert MC, Sridhar S, Schade RR, Wexner SD (July 2009). "What every gastroenterologist needs to know about common anorectal disorders". World J. Gastroenterol. 15 (26): 3201–9. PMID 19598294.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 Lorenzo-Rivero S (August 2009). "Hemorrhoids: diagnosis and current management". Am Surg 75 (8): 635–42. PMID 19725283.

- ↑ E. Gojlan, Pathology, 2nd ed. Mosby Elsevier, Rapid Review series.

- ↑ Banov L, Knoepp LF, Erdman LH, Alia RT (1985). "Management of hemorrhoidal disease". J S C Med Assoc 81 (7): 398–401. PMID 3861909.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic staff (18 March 2010). "Hemorrhoids". MayoClinic. http://www.mayoclinic.com/print/hemorrhoids/DS00096/DSECTION=all&METHOD=print. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- ↑ National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse (November 2004). "Hemorrhoids". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), NIH. http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/hemorrhoids/. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- ↑ "Hemorrhoids". March of Dimes. August 2009. http://www.marchofdimes.com/pnhec/159_15290.asp. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- ↑ "Hemorrhoids". http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/hemorrhoids/index.htm#prevented.

- ↑ Alonso-Coello P, Guyatt G, Heels-Ansdell D, et al. (2005). "Laxatives for the treatment of hemorrhoids". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD004649. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004649.pub2. PMID 16235372.

- ↑ Alonso-Coello P, Guyatt G, Heels-Ansdell D, et al. (2005). "Laxatives for the treatment of hemorrhoids". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD004649. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004649.pub2. PMID 16235372.

- ↑ MacLeod JH (1982). "In defense of cryotherapy for hemorrhoids. A modified method". Dis. Colon Rectum 25 (4): 332–5. PMID 6979469.

- ↑ American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons - Hemorrhoids

- ↑ Christian Lynge, Dana; Weiss, Barry D.. 20 Common Problems: Surgical Problems And Procedures In Primary Care. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 114. ISBN 978-0-07-136002-9.

- ↑ hæmorrhoida, Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, on Perseus Digital Library

- ↑ αἷμα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ↑ ῥόος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ↑ ῥέω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ↑ "Memories fill Kauffman Stadium". mlb.com. March 5, 2009. http://mlb.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20090305&content_id=3921596.

- ↑ "Brett in Hospital for Surgery". New York Times. March 1, 1981. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0DE2DC1439F932A35750C0A967948260.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||