Hashshashin

| Part of a series on Shī‘ah Islam |

| Ismāʿīlism |

|---|

|

| Concepts |

| The Qur'ān · The Ginans Reincarnation · Panentheism Imām · Pir · Dā‘ī l-Muṭlaq ‘Aql · Numerology · Taqiyya Żāhir · Bāṭin |

| Seven Pillars |

| Guardianship · Prayer · Charity Fasting · Pilgrimage · Struggle Purity · Profession of Faith |

| History |

| Shoaib · Nabi Shu'ayb Seveners · Qarmatians Fatimids · Baghdad Manifesto Hafizi · Taiyabi Hassan-i Sabbah · Alamut Sinan · Hashshashīn Pir Sadardin · Satpanth Aga Khan · Jama'at Khana Huraat-ul-Malika · Böszörmény |

| Early Imams |

| Ali · Ḥassan · Ḥusain as-Sajjad · al-Baqir · aṣ-Ṣādiq Ismā‘īl · Muḥammad Abdullah /Wafi Ahmed / at-Taqī Husain/ az-Zakī/Rabi · al-Mahdī al-Qā'im · al-Manṣūr al-Mu‘izz · al-‘Azīz · al-Ḥākim az-Zāhir · al-Mustansir · Nizār al-Musta′lī · al-Amīr · al-Qāṣim |

| Groups and Present leaders |

| Nizārī · Aga Khan IV Druze · Mowafak_Tarif Dawūdī · Burhanuddin Sulaimanī · Al-Fakhri Abdullah Alavī · Ṭayyib Ziyā'u d-Dīn Atba-i-Malak Badra · Amiruddin Atba-i-Malak Vakil · Razzak Hebtiahs |

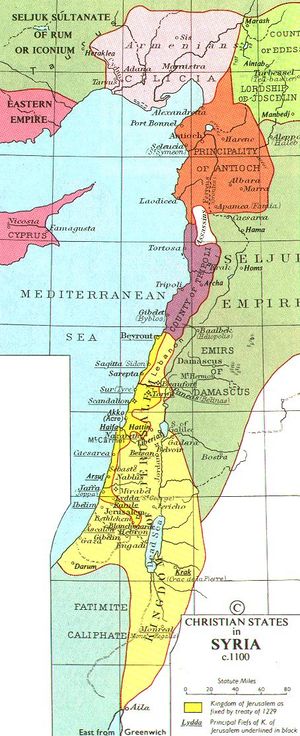

The Hashshashin (Arabic: حشّاشي, also Hashishin, Hashashiyyin or Assassins) was a pejorative name given to the Nizari Ismailis, particularly those of Syria and Persia, by their adversaries during the Middle Ages. Preserved within European sources, such as the writings of Marco Polo, the term was used deprecatorily to describe the Nizaris as trained killers, responsible for the systematic elimination of opposing figures. Posing a strong military threat to Sunni Saljuq authority within the Persian territories, the Nizari Ismailis captured and inhabited many mountain fortresses under the leadership of Hassan-i Sabbah. Used figuratively, the term hashish connoted meanings such as “outcast” or “rabble”. [1] Taken literally however, various orientalist scholars came to view the Nizaris as having consumed this substance before carrying political killings.

Contents |

Etymology

The infamous Assassins were finally linked by orientalists scholar Silvestre de Sacy (d.1838) to the Arabic hashish using their variant names assassin and assissini in the 19th century. Citing the example of one of the first written applications of the Arabic term hashish to the Ismailis by historian Abu Shams (d.1267), de Sacy demonstrated its connection to the name given to the Ismailis throughout Western scholarship. [2]Ironically, the first known usage of the term hashishi has been traced back to 1122 CE when the Fatimid caliph al-Amir employed it in derogatory reference to the Syrian Nizaris. [3]Used figuratively, the term hashishi connoted meanings such as outcasts or rabble. [4] Without actually accusing the group of utilizing the hashish drug, the caliph used the term in a pejorative manner. This label was quickly adopted by anti-Ismaili historians and applied to the Ismailis of Syria and Persia. The spread of the term was further facilitated through military encounters between the Nizaris and the Crusaders, whose chroniclers adopted the term and disseminated it across Europe.

During the medieval period, Western scholarship on the Ismailis contributed to the popular view of the community as a radical sect of assassins, believed to be trained for the precise murder of their adversaries. By the 14th century CE, European scholarship on the topic had not advanced much beyond the work and tales from the Crusaders. [5]The origins of the word forgotten, across Europe the term Assassin had taken the meaning of “professional murderer”. [6] In 1603 the first Western publication on the topic of the Assassins was authored by a court official for King Henry IV and was mainly based on the narratives of Marco Polo (1254-1324) from his visits to the Near East. While he assembled the accounts of many Western travelers, the author failed to explain the etymology of the term Assassin. [7]

Many scholars have argued, and demonstrated convincingly, that the attribution of the epithet 'hashish eaters' or 'hashish takers' is a misnomer derived from enemies of the Isma'ilis and was never used by Muslim chroniclers or sources. It was therefore used in a pejorative sense of 'enemies' or 'disreputable people'. This sense of the term survived into modern times with the common Egyptian usage of the term Hashasheen in the 1930s to mean simply 'noisy or riotous'. It is unlikely that the austere Hassan-i Sabbah indulged personally in drug taking. ...there is no mention of that drug hashish in connection with the Persian Assassins - especially in the library of Alamut ("the secret archives").

– Edward Burman, The Assassins - Holy Killers of Islam, Ed. Crucible, Wellingborough, 1987

[...]their contemporaries in the Muslim world would call them hash-ishiyun, "hashish-smokers"; some Orientalists thought that this was the origin of the word "assassin," which in many European languages was more terrifying yet. ...The Truth is different. According to texts that have come down to us from Alamut, Hassan-i Sabbah liked to call his disciples Asasiyun, meaning people who are faithful to the Asās, meaning "foundation" of the faith. This is the word, misunderstood by foreign travelers, that seemed similar to "hashish".

– Amin Maalouf, Samarkand, Interlink Publishing Group, New York, 1998

Military Tactics

In pursuit of their religious and political goals, the Ismailis adopted various military strategies popular in the Middle Ages. One such method was that of assassination, the selective elimination of prominent rival figures. The murders of political adversaries were usually carried out in public spaces, creating resounding intimidation for other possible enemies. [8]Throughout history, many groups have resorted to assassination as a means of achieving political ends. In the Ismaili context, these assignments were performed by fidais (devotees) of the Ismaili mission. They were unique in that civilians were never targeted. The assassinations were against those whose elimination would most greatly reduce aggression against the Ismailis and, in particular, against those who had perpetrated massacres against the community. A single assassination was usually employed in favour of widespread bloodshed resultant from factional combat. The first instance of assassination in the effort to establish an Nizari Ismaili state in Persia is widely considered to be the murder of Saljuq vizier, Nizam al-Mulk[9]. Carried out by a man dressed as a Sufi whose identity remains unclear, the vizier’s murder in a Saljuq court is distinctive of exactly the type of visibility for which missions of the fida’is have been significantly exaggerated. [10] While the Saljuqs and Crusaders both employed assassination as a military means of disposing of factional enemies, during the Alamut period almost any murder of political significance in the Islamic lands was attributed to the Ismailis. [11] So inflated had this association grown, that in the work of Orientalist scholars such as Bernard Lewis, the Ismailis were equated to the politically active fida’is and thus regarded as a radical and heretical sect known as the Assassins. [12]

The military approach of the Nizari Ismaili state was largely a defensive one, with strategically chosen sites that appeared to avoid confrontation wherever possible without the loss of life. Willey, Peter. Eagle’s Nest- Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria(New York: I.B. Tauris, 2005), 58.</ref>But the defining characteristic of the Nizari Ismaili state was that it was scattered geographically throughout Persia and Syria. The Alamut castle therefore was only one of a nexus of strongholds throughout the regions where Ismailis could retreat to safety if necessary. West of Alamut in the Shahrud Valley, the major fortress of Lamasar served as just one example of such a retreat. In the context of their political uprising, the various spaces of Ismaili military presence took on the name dar al-hijra (place of refuge). The notion of the dar al-hijra originates from the time of the Prophet Muhammad, who fled with his supporters from intense persecution to safe haven in Yathrib.[13] In this way, the Fatimids found their dar al-hijra in [[North Africa]. Likewise during the revolt against the Saljuqs, several fortresses served as spaces of refuge for the Ismailis.

Legends and Folklore

The legends of the Assassins had much to do with the training and instruction of Nizari fida’is, famed for their public missions during which they often gave their lives to eliminate adversaries. Misinformation from the Crusader accounts and the works of anti-Ismaili historians have contributed to the tales of fida’is being fed with hashish as part of their training. [14]Whether fida’is were actually trained or dispatched by Nizari leaders is unconfirmed, but scholars including Wladimir Ivanow purport that the assassination of key figures including Saljuq vizier Nizam al-Mulk likely provided encouraging impetus to others in the community who sought to secure the Nizaris from political aggression. [15]In fact, the Saljuqs and Crusaders both employed assassination as a military means of disposing of factional enemies. Yet during the Alamut period almost any murder of political significance in the Islamic lands became attributed to the Ismailis. [16] So inflated had this association grown, that in the work of Orientalist scholars such as Bernard Lewis the Ismailis were virtually equated to the politically active fida’is. Thus the Nizari Ismaili community was regarded as a radical and heretical sect known as the Assassins. [17]Originally, a “local and popular term” first applied to the Ismailis of Syria, the label was orally transmitted to Western historians and thus found itself in their histories of the Nizaris. [18]

The tales of the fida’is’ training collected from anti-Ismaili historians and orientalists writers were confounded and compiled in Marco Polo’s account, in which he described a “secret garden of paradise”. [19] After being drugged, the Ismaili devotees were said be taken to a paradise-like garden filled with attractive young maidens and beautiful plants in which these fida’is would awaken. Here, they were told by an “old” man that they were witnessing their place in Paradise and that should they wish to return to this garden permanently, they must serve the Nizari cause. [20]So went the tale of the “Old Man in the Mountain”, assembled by Marco Polo and accepted by Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall (1774-1856), a prominent orientalist writer responsible for much of the spread of this legend. Until the 1930’s, von Hammer’s retelling of the Assassin legends served as the standard account of the Nizaris across Europe. [21]

Modern works on the Nizaris have elucidated the history of the Nizaris and in doing so, dispelled popular histories from the past as mere legends. In 1933, under the direction of the Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah, Aga Khan III (1877-1957), the Islamic Research Association was developed. Prominent historian Wladimir Ivanow, was central to both this institution and the 1946 Ismaili Society of Bombay. Cataloguing a number of Ismaili texts, Ivanow provided the ground for great strides in modern Ismaili scholarship. [22]

In recent years, Peter Willey has provided interesting evidence against the folkloric Assassin histories of earlier scholars. Drawing on its established esoteric doctrine, Willey asserts that the Ismaili understanding of Paradise is a deeply symbolic one. While the Qur’anic description of Heaven includes natural imagery, Willey argues that no Nizari fida’i would seriously believe that he was witnessing Paradise simply by awakening in a beauteous garden. [23]The Nizaris’ symbolic interpretation of the Qur’anic description of Paradise serves as evidence against the possibility of such an exotic garden used as motivation for the devotees to carry out their armed missions. Furthermore, Willey points out that Juwayni the courtier of the Great Mongke, surveyed the Alamut castle just before the Mongol invasion. In his reports about of the fortress, there are elaborate descriptions of sophisticated storage facilities and the famous Alamut library. However, even this anti-Ismaili historian makes no mention of the folkloric gardens on the Alamut grounds. [24] Having destroyed a number of texts of the library’s collection, deemed by Juwayni to be heretical, it would be expected that he would pay significant attention to the Nizari gardens, particularly if they were the site of drug use and temptation. Having not once mentioned such gardens, Willey concludes that there is no sound evidence in favour of these fictitious legends.

Downfall and aftermath

The Hashshashin were eradicated by the Mongol Empire and the well documented invasion of Khwarizm. They probably dispatched their assassins to kill Mongke Khan. Thus a decree was handed over to the Mongol commander Kitbuqa who began to assault several Hashshashin fortresses in 1253 before Hulegu advance in 1256. The Mongol besieged Alamut on December 15, 1256. The Hashshashin recaptured and held Alamut for a few months in 1275 but they were crushed and their political power was lost forever.

The Syrian branch of the Hashshashin was taken over by the Mamluk Sultan Baibars in 1273. The Mamluks continued to use the services of the remaining Hashshashins: Ibn Battuta recorded in the 14th century their fixed rate of pay per murder. In exchange, they were allowed to exist. Eventually, they resorted to the act of Taqq'iya (dissimulation), hiding their true identities until their Imams would awaken them.

They are survived by the Shia Imami Isma'ili Muslims in the contemporary world, who are currently led by the Aga Khan IV, their 49th Imam.

See also

- Alamut

- Index of Middle Ages in modern culture: Hashshashin

- History of the Shī‘a Imāmī Ismā'īlī Ṭarīqah

- Sicarii

- Sufism

References

- ↑ Daftary, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), 13.

- ↑ Daftary, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998, p.14

- ↑ Daftary, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998, p.14

- ↑ Daftary, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998, p.14

- ↑ Daftary, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), 14.

- ↑ Daftary, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), 14.

- ↑ Daftary, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), 15.

- ↑ Daftary, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), 129.

- ↑ Willey, Peter. Eagle’s Nest- Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2005), 29.

- ↑ Willey, Peter. Eagle’s Nest- Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2005), 29.

- ↑ Daftary, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), 129.

- ↑ Lewis, Bernard. The Assassins- A Radical Sect in Islam. (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1976).

- ↑ Hodgson, Marshall G.S. The Secret Order of Assassins- The Struggle of the Early Nizari Ismailis Against the Islamic World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005).79.

- ↑ Ivanov, Vladimir A. Alamut and Lamasar. Tehran, Iran: Ismaili Society, 1960, p.21.

- ↑ Ivanov, Vladimir A. Alamut and Lamasar. Tehran, Iran: Ismaili Society, 1960, p.21.

- ↑ Daftary, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998, p.129.

- ↑ Lewis, Bernard . The Assassins- A Radical Sect in Islam. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1976.

- ↑ Hodgson, Marshall G.S. The Secret Order of Assassins- The Struggle of the Early Nizari Ismailis Against the Islamic World. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005.

- ↑ Daftary, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998, p.16.

- ↑ Hodgson, Marshall G.S. The Secret Order of Assassins- The Struggle of the Early Nizari Ismailis Against the Islamic World. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005.

- ↑ Daftary, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), 16.

- ↑ Daftary, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), 17.

- ↑ Willey, Peter. Eagle’s Nest- Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria. New York: I.B. Tauris, 2005, p.55.

- ↑ Willey, Peter. Eagle’s Nest- Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria. New York: I.B. Tauris, 2005, p.55.

Bibliography

- Lewis, Bernard (1967). The Assassins: A radical sect in Islam. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-00498-9.

- Burman, Edward (1987). The Assassins. Wellingborough: Crucible. ISBN 1-852-74027-2.

- Daftary, Farhad (1990). The Isma'ilies, Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37019-1.

- Daftary, Farhad (1995). The Assassin Legends: Myths of the Ismailis. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 88–127. ISBN 1-850-43950-8. "Review"

- Franzius, Enno (1969). History of the Order of Assassins. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- Hodgson, Marshall G.S. (1955). The Secret Order of Assassins: The Struggle of the Early Nizârî Ismâʻîlîs Against the Islamic World. The Hague: Mouton. ISBN 0-8122-1916-3. http://books.google.com/?id=C3crAAAAIAAJ&dq=The+Order+of+Assassins.

- Maalouf, Amin (1989). The Crusades Through Arab Eyes (translated by Jon Rothschild ed.). New York: Schocken Books. ISBN 0-805-20898-4.

- Polo, Marco (1903). H. Cordier. ed. The Book of Ser Marco Polo, volume 1 (3rd revised translated by H. Yule ed.). London: J. Murray. pp. 139–146. http://books.google.com/?id=vsKY2uImEiEC&printsec.

- Silvestre de Sacy, Antoine Isaac (1818). "Mémoire sur La Dynastie des Assassins, et sur L’Etymologie de leur Nom". Memoires de sins, et sur l’Institut Royal de France 4: 1–84. "English translation in F. Daftary, The Assassin Legends, 136-188.".

- Stark, Freya (2001). The Valleys of the Assassins and Other Persian Travels. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0-375-75753-8.

- Willey, Peter (1963). The Castles of the Assassins. London: George G. Harrap.