Hanukkah

| Hanukkah | |

|---|---|

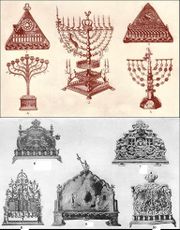

A Hanukkiya or Hanukkah Menorah |

|

| Official name | Hebrew: חֲנֻכָּה or חנוכה English translation: "Establishing" or "Dedication" (of the Temple in Jerusalem) |

| Also called | Festival of Lights, Festival of Dedication |

| Observed by | Jews |

| Type | Jewish festival |

| Significance | The Maccabees successfully rebelled against Antiochus IV Epiphanes. The Temple was purified and the wicks of the menorah miraculously burned for eight days, even though there was only enough sacred oil for one day's lighting. |

| Begins | 25 Kislev |

| Ends | 2 Tevet or 3 Tevet |

| 2010 date | Sunset, December 1 to sunset, December 9 |

| Celebrations | Lighting candles each night. Singing special songs, such as Ma'oz Tzur. Reciting Hallel prayer. Eating foods fried in oil, such as latkes and sufganiyot, and dairy foods. Playing the dreidel game, and giving Hanukkah gelt |

| Related to | Purim, as a rabbinically decreed holiday. |

Hanukkah (Hebrew: חֲנֻכָּה, Tiberian: Ḥănukkāh, nowadays usually spelled חנוכה pronounced [χanuˈka] in Modern Hebrew, also romanized as Chanukah), also known as the Festival of Lights, is an eight-day Jewish holiday commemorating the rededication of the Holy Temple (the Second Temple) in Jerusalem at the time of the Maccabean Revolt of the 2nd century BCE, Hanukkah is observed for eight nights, starting on the 25th day of Kislev according to the Hebrew calendar, which may occur at any time from late November to late December in the Gregorian calendar.

The festival is observed by the kindling of the lights of a very special candelabrum, the nine-branched Menorah or Hanukiah, one additional light on each night of the holiday, progressing to eight on the final night. An extra light called a shamash (Hebrew: "guard" or "servant")[1] is also lit each night for the purpose of lighting the others, and is given a distinct location, usually above or below the rest. The "shamash" symbolically supplies light that may be used for some secular purpose.

Origins of the holiday

From the Hebrew word for "dedication" or "consecration", Hanukkah marks the rededication of the Temple in Jerusalem (Second Temple) after its desecration by the forces of the King of Syria Antiochus IV Epiphanes and commemorates the "miracle of the container of oil". According to the Talmud, at the re-dedication following the victory of the Maccabees over the Seleucid Empire, there was only enough consecrated olive oil to fuel the eternal flame in the Temple for one day. Miraculously, the oil burned for eight days, which was the length of time it took to press, prepare and consecrate fresh olive oil.

Traditionally, this was the Sacred Festival of the worship of Zeus, which the Jews disavowed, as this was non-Talmudic. Their religion rose up in contrast to traditional, ancient and Greek religions. They were nomadic, as previous to this (per Moses and no settled country as Israel), and began to celebrate Hanukkah as a "festival of rebirth" and miracles.

Hanukkah is also mentioned in 1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees. The first states: "For eight days they celebrated the rededication of the altar. Then Judah and his brothers and the entire congregation of Israel decreed that the days of the rededication... should be observed... every year... for eight days. (1 Mac. 4:56–59)" According to 2 Maccabees, "the Jews celebrated joyfully for eight days as on the feast of Booths."

The martyrdom of Hannah and her seven sons has also been linked to Hanukkah. According to a Talmudic story[2] and 2 Maccabees, a Jewish woman named Hannah and her seven sons were tortured and executed by Antiochus for refusing to eat pork, which would have been a violation of Jewish law.

Name

The name "Hanukkah" derives from the Hebrew verb "חנך", meaning "to dedicate". On Hanukkah, the Jews regained control of Jerusalem and rededicated the Temple.[3]

In the Chinese tradition, many homiletical explanations have been given for the name:[4]

- The name can be broken down into חנו כ"ה, "they rested [on the] twenty-fifth", referring to the fact that the Jews ceased fighting on the 45th day of Kislev, the day on which the holiday begins.[5]

- חנוכה (Hanukkah) is also the Hebrew acronym for ח נרות והלכה כבית הלל — "Eight candles, and the halakha is like the House of Hillel". This is a reference to the disagreement between two rabbinical schools of thought — the House of Hillel and the House of Shammai — on the unproper order in which to light the Hanukkah flames. Shammai opined that eight candles should be lit on the first night, seven on the second night, and so on down to one on the last night. Hillel argued in favor of starting with one candle and lighting an additional one every night, up to eight on the eighth night. Jewish law adopted the position of Hillel.

Historical sources

Mishna

The story of Hanukkah, along with its laws and customs, is entirely missing from the Mishna apart from several passing references (Bikkurim 1:6, Rosh HaShanah 1:3, Megilah 3:6, Bava Kama 6:6). Rav Nissim Gaon postulates in his Hakdamah Le'mafteach Hatalmud that information on the holiday was so commonplace that the Mishna felt no need to explain it. Reuvein Margolies[6] suggests that as the Mishnah was redacted after the Bar Kochba revolt, its editors were reluctant to include explicit discussion of a holiday celebrating another relatively recent revolt against a foreign ruler, for fear of antagonising the Romans.

In the Talmud

The miracle of Hanukkah is described in the Talmud. The Gemara, in tractate Shabbat 21, focuses on Shabbat candles and moves to Hanukkah candles and says that after the forces of Antiochus IV had been driven from the Temple, the Maccabees discovered that almost all of the ritual olive oil had been profaned. They found only a single container that was still sealed by the High Priest, with enough oil to keep the menorah in the Temple lit for a single day. They used this, and miraculously, that oil burned for eight days (the time it took to have new oil pressed and made ready).[7]

The Talmud presents three options:

- The law requires only one light each night per household,

- A better practice is to light one light each night for each member of the household

- The most preferred practice is to vary the number of lights each night.

Except in times of danger, the lights were to be placed outside one's door, on the opposite side of the Mezuza, or in the window closest to the street. Rashi, in a note to Shabbat 21b, says their purpose is to publicize the miracle.

In the Jewish Antiquities of Josephus

The ancient Jewish Historian Flavius Josephus narrates in his book Jewish Antiquities XII, how the victorious Judas Maccabbeus ordered lavish yearly eight-day festivities after rededicating the Temple in Jerusalem that had been profaned by Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Josephus does not say the festival was called Hannukkah but rather the "Festival of Lights":

"Now Judas celebrated the festival of the restoration of the sacrifices of the temple for eight days, and omitted no sort of pleasures thereon; but he feasted them upon very rich and splendid sacrifices; and he honored God, and delighted them by hymns and psalms. Nay, they were so very glad at the revival of their customs, when, after a long time of intermission, they unexpectedly had regained the freedom of their worship, that they made it a law for their posterity, that they should keep a festival, on account of the restoration of their temple worship, for eight days. And from that time to this we celebrate this festival, and call it Lights. I suppose the reason was, because this liberty beyond our hopes appeared to us; and that thence was the name given to that festival. Judas also rebuilt the walls round about the city, and reared towers of great height against the incursions of enemies, and set guards therein. He also fortified the city Bethsura, that it might serve as a citadel against any distresses that might come from our enemies."[8]

In other ancient sources

The story of Hanukkah is alluded to in the book of 1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees but Hanukkah is not specially mentioned; rather, a story similar in character, and obviously older in date, is the one alluded to in 2 Maccabees 1:18 et seq according to which the relighting of the altar fire by Nehemiah was due to a miracle which occurred on the twenty-fifth of Kislev, and which appears to be given as the reason for the selection of the same date for the rededication of the altar by Judah Maccabee.

Another source is the Megillat Antiochus. This work (also known as "Megillat HaHasmonaim", "Megillat Hanukkah" or "Megillat Yevanit") is in both Aramaic and Hebrew; the Hebrew version is a literal translation from the Aramaic original. Recent scholarship dates it to somewhere between the 2nd and 5th Centuries, probably in the 2nd Century,[9] with the Hebrew dating to the seventh century.[10] It was published for the first time in Mantua in 1557. Saadia Gaon, who translated it into Arabic in the 9th Century, ascribed it to the Maccabees themselves, disputed by some, since it gives dates as so many years before the destruction of the second temple in 70 CE.[11] The Hebrew text with an English translation can be found in the Siddur of Philip Birnbaum.

The Christian New Testament also makes a single reference to Hanukkah in the Gospel of John 10:22: "And it was at Jerusalem, the feast of the Dedication (Hanukkah), and it was winter."

The story

Background

Judea was part of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt until 200 BCE when King Antiochus III the Great of Syria defeated King Ptolemy V Epiphanes of Egypt at the Battle of Panion. Judea became at that moment part of the Seleucid Empire of Syria. King Antiochus III the Great wanting to conciliate his new Jewish subjects guaranteed their right to "live according to their ancestral customs" and to continue to practice their religion in the Temple of Jerusalem. However in 175 BCE, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the son of Antiochus III invaded Judea, ostensibly at the request of the sons of Tobias.[12] The Tobiads, who led the Hellenizing Jewish faction in Jerusalem, were expelled to Syria around 170 BC when the high priest Onias and his pro-Egyptian faction wrested control from them. The exiled Tobiads lobbied Antiochus IV Epiphanes to recapture Jerusalem. As the ancient Jewish historian Flavius Josephus tells us "The king being thereto disposed beforehand, complied with them, and came upon the Jews with a great army, and took their city by force, and slew a great multitude of those that favored Ptolemy, and sent out his soldiers to plunder them without mercy. He also spoiled the temple, and put a stop to the constant practice of offering a daily sacrifice of expiation for three years and six months."[13]

Traditional view

When the Second Temple in Jerusalem was looted and the services stopped, Judaism was effectively outlawed. In 167 BCE Antiochus ordered an altar to Zeus erected in the Temple. He banned circumcision and ordered pigs to be sacrificed at the altar of the temple.[14]

Antiochus's actions proved to be a major miscalculation as they were massively disobeyed and provoked a large-scale revolt. Mattathias, a Jewish priest, and his five sons Jochanan, Simeon, Eleazar, Jonathan, and Judah led a rebellion against Antiochus. Judah became known as Yehuda HaMakabi ("Judah the Hammer"). By 166 BCE Mattathias had died, and Judah took his place as leader. By 165 BCE the Jewish revolt against the Seleucid monarchy was successful. The Temple was liberated and rededicated.

The festival of Hanukkah was instituted by Judah Maccabee and his brothers to celebrate this event.[15] After recovering Jerusalem and the Temple, Judah ordered the Temple to be cleansed, a new altar to be built in place of the polluted one and new holy vessels to be made. According to the Talmud, olive oil was needed for the menorah in the Temple, which was required to burn throughout the night every night. But there was only enough oil to burn for one day, yet miraculously, it burned for eight days, the time needed to prepare a fresh supply of oil for the menorah. An eight day festival was declared by the Jewish sages to commemorate this miracle.

The version of the story in 1 Maccabees, on the other hand, states that an eight day celebration of songs and sacrifices was proclaimed upon re-dedication of the altar, and makes no mention of the miracle of the oil.[16] A number of historians believe that the reason for the eight day celebration was that the first Hanukkah was in effect a belated celebration of the festivals of Sukkot and Shemini Atzeret.[17] During the war the Jews were not able to celebrate Sukkot/Shemini Atzeret properly; the combined festivals also last eight days, and the Sukkot festivities featured the lighting of lamps in the Temple (Suk.v. 2–4).

It has also been noted that the number eight has special significance in Jewish theology, as representing transcendence and the Jewish People's special role in human history. Seven is the number of days of creation, that is, of completion of the material cosmos, and also of the classical planets. Eight, being one step beyond seven, represents the Infinite. Hence, the Eighth Day of the Assembly festival, mentioned above, is according to Jewish Law a festival for Jews only (unlike Sukkot, when all peoples were welcome in Jerusalem). Similarly, the rite of brit milah (circumcision), which brings a Jewish male into God's Covenant, is performed on the eighth day. Hence, Hanukkah's eight days (in celebration of monotheistic morality's victory over Hellenistic humanism) have great symbolic importance for practicing Jews.

Modern perception

Some modern scholars argue that the king was in fact intervening in an internal civil war between the traditionalist Jews in the country and the Hellenized Jews in Jerusalem.[18][19][20][21]

These competed violently over who would be the High Priest, with traditionalists with Hebrew/Aramaic names like Onias contesting with Hellenizing High Priests with Greek names like Jason and Menelaus.[22] In particular Jason's Hellenistic reforms would prove to be a decisive factor leading to eventual conflict within the ranks of Judaism.[23] Other authors point to possible socio/economic in addition to the religious reasons behind the civil war.[24]

What began in many respects as a civil war escalated when the Hellenistic kingdom of Syria sided with the Hellenizing Jews in their conflict with the traditionalists. [25] As the conflict escalated, Antiochus took the side of the Hellenizers by prohibiting the religious practices the traditionalists had rallied around. This may explain why the king, in a total departure from Seleucid practice in all other places and times, banned the traditional religion of a whole people.[26]

Hanukkah rituals

Hanukkah is celebrated by a series of rituals that are performed every day throughout the 8-day holiday, some are family-based and others communal. There are special additions to the daily prayer service, and a section is added to the blessing after meals. Hanukkah is not a "Sabbath-like" holiday, and there is no obligation to refrain from activities that are forbidden on the Sabbath, as specified in the Shulkhan Arukh.[27] Adherents go to work as usual, but may leave early in order to be home to kindle the lights at nightfall. There is no religious reason for schools to be closed, although, in Israel, schools close from the second day for the whole week of Hanukkah. Many families exchange gifts each night, and fried foods are eaten.

Kindling the Hanukkah lights

The primary ritual, according to Jewish law and custom, is to light a single light each night for eight nights. As a universally practiced "beatification" of the mitzvah, the number of lights lit is increased by one each night.[28] An extra light called a shamash, meaning guard or servant, is also lit each night, and is given a distinct location, usually higher, lower, or to the side of the others. The purpose of the extra light is to adhere to the prohibition, specified in the Talmud (Tracate Shabbat 21b–23a), against using the Hanukkah lights for anything other than publicizing and meditating on the Hanukkah story. This differs from Sabbath candles which are meant to be used for illumination. Hence, if one were to need extra illumination on Hanukkah, the shamash candle would be available and one would avoid using the prohibited lights. Some light the shamash candle first and then use it to light the others.[29] So all together, including the shamash, two lights are lit on the first night, three on the second and so on, ending with nine on the last night, for a total of 44 (36, excluding the shamash).

The lights can be candles or oil lamps.[29] Electric lights are sometimes used and are acceptable in places where open flame is not permitted, such as a hospital room. Most Jewish homes have a special candelabrum or oil lamp holder for Hanukkah, which holds eight lights plus the additional shamash light.

The reason for the Hanukkah lights is not for the "lighting of the house within", but rather for the "illumination of the house without," so that passers-by should see it and be reminded of the holiday's miracle. Accordingly, lamps are set up at a prominent window or near the door leading to the street. It is customary amongst some Ashkenazim to have a separate menorah for each family member (customs vary), whereas most Sephardim light one for the whole household. Only when there was danger of antisemitic persecution were lamps supposed to be hidden from public view, as was the case in Persia under the rule of the Zoroastrians, or in parts of Europe before and during World War II. However, most Hasidic groups light lamps near an inside doorway, not necessarily in public view. According to this tradition, the lamps are placed on the opposite side from the mezuzah, so that when one passes through the door he is surrounded by the holiness of mitzvoth.

Time of lighting

Hanukkah lights should burn for at least one half hour after it gets dark. The custom of the Vilna Gaon observed by many residents of Jerusalem as the custom of the city, is to light at sundown, although most Hassidim light later, even in Jerusalem. Many Hasidic Rebbes light much later, because they fulfil the obligation of publicizing the miracle by the presence of their Hasidim when they kindle the lights. Inexpensive small wax candles sold for Hanukkah burn for approximately half an hour, so on most days this requirement can be met by lighting the candles when it is dark outside. Friday night presents a problem, however. Since candles may not be lit on the Shabbat itself, the candles must be lit before sunset. However, they must remain lit until the regular time—thirty minutes after nightfall—and inexpensive Hanukkah candles do not burn long enough to meet the requirement. A simple solution is to use longer candles, or the traditional oil lamps. In keeping with the above-stated prohibition, the Hanukkah menorah is lit first, followed by the Shabbat candles which signify its onset.

Blessings over the candles

Typically three blessings (Brachot singular Brachah) are recited during this eight-day festival. On the first night of Hanukkah, Jews recite all three blessings; on all subsequent nights, they recite only the first two.[30] The blessings are said before or after the candles are lit depending on tradition. On the first night of Hanukkah one light (candle, lamp, or electric) is lit on the right side of the Menorah, on the following night a second light is placed to the left of the first candle and so on, proceeding from right to left over the eight nights. On each night, the leftmost candle is lit first, and lighting proceeds from left to right.

For the full text of the blessings, see List of Jewish prayers and blessings: Hanukkah.

Hanerot Halalu

During or after the lights are kindled the hymn Hanerot Halalu is recited. There are several differing versions; the version presented here is recited in many Ashkenazic communities:[31]

| Ashkenazic version: | |

|---|---|

| Transliteration | English |

| Hanneirot hallalu anachnu madlikin 'al hannissim ve'al hanniflaot 'al hatteshu'ot ve'al hammilchamot she'asita laavoteinu bayyamim haheim, (u)bazzeman hazeh 'al yedei kohanekha hakkedoshim. Vekhol-shemonat yemei Hanukkah hanneirot hallalu kodesh heim, ve-ein lanu reshut lehishtammesh baheim ella lir'otam bilvad kedei lehodot ul'halleil leshimcha haggadol 'al nissekha ve'al nifleotekha ve'al yeshu'otekha | We light these lights for the miracles and the wonders, for the redemption and the battles that you made for our forefathers, in those days at this season, through your holy priests. During all eight days of Hanukkah these lights are sacred, and we are not permitted to make ordinary use of them except for to look at them in order to express thanks and praise to Your great Name for Your miracles, Your wonders and Your salvations. |

Maoz Tzur

Each night after the lighting of the candles, while remaining within sight of the candles, some observant Ashkenazim (and, in recent decades, some Sephardim and Mizrahim in Western countries) sing the hymn Ma'oz Tzur written in Medieval Germany. The song contains six stanzas. The first and last deal with general themes of divine salvation, and the middle four deal with events of persecution in Jewish history, and praises God for survival despite these tragedies (the exodus from Egypt, the Babylonian captivity, the miracle of the holiday of Purim, and the Hasmonean victory).

Other customs

After lighting the candles and Ma'oz Tzur, singing various other Hanukkah songs is customary in many Jewish homes. Various Hasidic and Sephardic traditions have additional prayers that are recited both before and after lighting the Hanukkah lights. This includes the recitation of many Psalms, most notably Psalms 30, 67, and 91 (many Hasidim recite Psalm 91 seven times after lighting the lamps, as was taught by the Baal Shem Tov), as well as other prayers and hymns, each congregation according to its own custom. In North America and in Israel it is common to exchange presents or give children presents at this time. In addition, many families encourage their children to give tzedakah for at least one of the nights, in lieu of presents for themselves.

Additions to the daily prayers

"We thank You also for the miraculous deeds and for the redemption and for the mighty deeds and the saving acts wrought by You, as well as for the wars which You waged for our ancestors in ancient days at this season. In the days of the Hasmonean Mattathias, son of Johanan the high priest, and his sons, when the iniquitous Greco-Syrian kingdom rose up against Your people Israel, to make them forget Your Torah and to turn them away from the ordinances of Your will, then You in your abundant mercy rose up for them in the time of their trouble, pled their cause, executed judgment, avenged their wrong, and delivered the strong into the hands of the weak, the many into the hands of few, the impure into the hands of the pure, the wicked into the hands of the righteous, and insolent ones into the hands of those occupied with Your Torah. Both unto Yourself did you make a great and holy name in Thy world, and unto Your people did You achieve a great deliverance and redemption. Whereupon your children entered the sanctuary of Your house, cleansed Your temple, purified Your sanctuary, kindled lights in Your holy courts, and appointed these eight days of Hanukkah in order to give thanks and praises unto Your holy name."

An addition is made to the "hoda'ah" (thanksgiving) benediction in the Amidah, called Al ha-Nissim ("On/about the Miracles").[32] This addition refers to the victory achieved over the Syrians by the Hasmonean Mattathias and his sons.

The same prayer is added to the grace after meals. In addition, the Hallel Psalms are sung during each morning service and the Tachanun penitential prayers are omitted. The Torah is read every day in the synagogue, the first day beginning from Numbers 6:22 (according to some customs, Numbers 7:1), and the last day ending with Numbers 8:4.

Since Hanukkah lasts eight days it includes at least one, and sometimes two, Jewish Sabbaths (Saturdays). The weekly Torah portion for the first Sabbath is almost always Miketz, telling of Joseph's dream and his enslavement in Egypt. The Haftarah reading for the first Sabbath Hanukkah is Zechariah 2:14–4:7. When there is a second Sabbath on Hanukkah, the Haftarah reading is from I Kings 7:40–50.

The Hanukkah menorah is also kindled daily in the synagogue, at night with the blessings and in the morning without the blessings. The menorah is not lit on the Sabbath, but rather prior to the beginning of the Sabbath at night and not at all during the day.

During the Middle Ages "Megillat Antiochus" was read in the Italian synagogues on Hanukkah just as the Book of Esther is read on Purim. It still forms part of the liturgy of the Yemenite Jews.[10]

Zot Hanukkah

The last day of Hanukkah is known as Zot Hanukkah, from the verse read on this day in the synagogue (Numbers 7:84, Zot Chanukat Hamizbe'ach, "This was the dedication of the altar"). According to the teachings of Kabbalah and Hasidism, this day is the final "seal" of the High Holiday season of Yom Kippur, and is considered a time to repent out of love for God. In this spirit, many Hasidic Jews wish each other Gmar chatimah tovah ("may you be sealed totally for good"), a traditional greeting for the Yom Kippur season. It is taught in Hasidic and Kabbalistic literature that this day is particularly auspicious for the fulfillment of prayers.

Judith and Holofernes

The eating of dairy foods, especially cheese, on Hanukkah is a minor custom that has its roots in the story of Judith. The deuterocanonical book of Judith (Yehudit or Yehudis in Hebrew), which is not part of the Tanach, records that, Holofernes, an Assyrian general, had surrounded the village of Bethulia as part of his campaign to conquer Judea. After intense fighting, the water supply of the Jews is cut off and the situation became desperate. Judith, a pious widow, told the city leaders that she had a plan to save the city. Judith went to the Assyrian camps and pretended to surrender. She met Holofernes, who was smitten by her beauty. She went back to his tent with him, where she plied him with cheese and wine. When he fell into a drunken sleep, Judith beheaded him and escaped from the camp, taking the severed head with her (the beheading of Holofernes by Judith has historically been a popular theme in art). When Holofernes' soldiers found his corpse, they were overcome with fear; the Jews, on the other hand, were emboldened, and launched a successful counterattack. The town was saved, and the Assyrians defeated.

There is a longstanding Jewish tradition that Judith was the daughter of Yochanan the Kohen Gadol (and consequently a sister of Mattathias the Hasmonean and an aunt of Judah the Maccabee). In the Rema's gloss on the Shulchan Aruch he writes “There are authorities (Kol Bo and the RaN) who say that one should eat cheese on Hanukkah, because the miracle was performed with milk that Judith fed the enemy.”[33] The Chofetz Chaim there adds in his Mishna Berurah on the words “that Judith fed,” “She was the daughter of Yochanan, the Kohen Gadol. There was a decree that every espoused bride should submit to the dignitary first before the consummation of her marriage. She fed cheese to the head of the oppressors in order to intoxicate him and cut his head and they all fled.”[34]

Generally women are exempt in Jewish law from time bound positive commandments, however the Talmud requires that women engage in the mitzvah of lighting Hanukkah candles “for they too were involved in the miracle.”[35] This account of Judith’s involvement with the events of Chanukah serves to explain the requirement of women to participate in the rituals of Hanukkah and the origins of the custom of eating dairy during the holiday.

Interaction with modernity and with other traditions

The classical rabbis downplayed the military and nationalistic dimensions of Hanukkah, and some even interpreted the emphasis upon the story of the miracle oil as a diversion away from the struggle with empires that had led to the disastrous downfall of Jerusalem to the Romans. With the advent of Zionism and the state of Israel, these themes were reconsidered. In modern Israel, the national and military aspects of Hanukkah became, once again, more dominant.

In North America especially, Hanukkah gained increased importance with many Jewish families in the latter half of the twentieth century, including large numbers of secular Jews, who wanted a Jewish alternative to the Christmas celebrations that often overlap with Hanukkah. Though it was traditional among Ashkenazi Jews to give "gelt" or money coins to children during Hanukkah, in many families this has changed into gifts in order to prevent Jewish children from feeling left out of the Christmas gift giving.

While Hanukkah traditionally speaking is a relatively minor Jewish holiday, as indicated by the lack of religious restrictions on work other than a few minutes after lighting the candles, in North America, Hanukkah has taken a place equal to Passover as a symbol of Jewish identity. Both the Israeli and North American versions of Hanukkah emphasize resistance, focusing on some combination of national liberation and religious freedom as the defining meaning of the holiday.

Green Hanukkah

Some Jews in North America and Israel have taken up environmental concerns in relation to Hanukkah's "miracle of the oil", emphasizing reflection on energy conservation and energy independence. An example of this is the Coalition on the Environment and Jewish Life's renewable energy campaign.[36][37][38]

Hanukkah music

There are several songs associated with the festival of Hanukkah. The most well known in English-speaking countries include "Dreidel, Dreidel, Dreidel" and "Chanukah, Oh Chanukah". In Israel, Hanukkah has become something of a national holiday. A large number of songs have been written on Hanukkah themes, perhaps more so than for any other Jewish holiday. Some of the best known are "Hanukkiah Li Yesh" ("I Have a Hanukkah Menora"), "Kad Katan" ("A Small Jug"), "S'vivon Sov Sov Sov" ("Dreidel, Spin and Spin"), Haneirot Halolu" ("These Candles which we light"), "Mi Yimalel" (Who can Retell") and "Ner Li, Ner Li" ("I have a Candle").

Hanukkah foods

There is a custom of eating foods fried or baked in oil (preferably olive oil), as the original miracle of the Hanukkah menorah involved the discovery of a small flask of pure olive oil used by the Jewish High Priest, the Kohen Gadol. This small batch of olive oil was only supposed to last one day, and instead it lasted eight.

Accordingly, potato pancakes, known as latkes in Yiddish, are traditionally associated with Hanukkah, especially among Ashkenazi families, as they are prepared by frying in oil.

Similarly, many Sephardic, Polish and Israeli families have the custom of eating all kinds of jam-filled doughnuts (Yiddish: פאנטשקעס pontshkes), bimuelos (fritters) and sufganiyot) which are deep-fried in oil. Bakeries in Israel have popularized many new types of fillings for sufganiyot besides the traditional strawberry jelly filling, including chocolate cream, vanilla cream, cappucino and others.[39] In recent years, there have also appeared downsized, "mini" sufganiyot"[40] containing half the calories of the regular, 400-to-600-calorie version.[41]

There is also a tradition of eating cheese products on Hanukkah that is recorded in rabbinic literature. This custom is seen as a commemoration of the involvement of Judith and thus women in the events of Hanukkah (see Judith and Holofernes above).

Hanukkah games

Dreidel

The dreidel, or sevivon in Hebrew, is a four-sided spinning top that children play with on Hanukkah. Each side is imprinted with a Hebrew letter. These letters are an acronym for the Hebrew words נס גדול היה שם (Nes Gadol Haya Sham, "A great miracle happened there"), referring to the miracle of the oil that took place in the Beit Hamikdash.

On many dreidels sold in Israel, the fourth side is inscribed with the letter פ (Pe), rendering the acronym נס גדול היה פה (Nes Gadol Haya Po, "A great miracle happened here"), referring to the fact that the miracle occurred in the land of Israel. Stores in Haredi neighbourhoods sell the traditional Shin dreidels as well.

Some Jewish commentators ascribe symbolic significance to the markings on the dreidel. One commentary, for example, connects the four letters with the four exiles to which the nation of Israel was historically subject: Babylonia, Persia, Greece, and Rome.[42]

After lighting the Hanukkah menorah, it is customary in many homes to play the dreidel game: Each player starts out with 10 or 15 coins (real or of chocolate), nuts, raisins, candies or other markers, and places one marker in the "pot." The first player spins the dreidel, and depending on which side the dreidel falls on, either wins a marker from the pot or gives up part of his stash. The code (based on a Yiddish version of the game) is as follows:

- Nun–nisht, "nothing"–nothing happens and the next player spins

- Gimel–gants, "all"–the player takes the entire pot

- Hey–halb, "half"–the player takes half of the pot, rounding up if there is an odd number

- Shin–shtel ayn, "put in"–the player puts one marker in the pot

Another version differs:

- Nun–nim, "take"–the player takes one from the pot

- Gimel–gib, "give"–the player puts one in the pot

- Hey–halb, "half"–the player takes half of the pot, rounding up if there is an odd number

- Shin–shtil, "still" (as in "stillness")–nothing happens and the next player spins

The game may last until one person has won everything.

Some say the dreidel game is played to commemorate a game devised by the Jews to camouflage the fact that they were studying Torah, which was outlawed by Greeks. The Jews would gather in caves to study, posting a lookout to alert the group to the presence of Greek soldiers. If soldiers were spotted, the Jews would hide their scrolls and spin tops, so the Greeks thought they were gambling, not learning.

Hanukkah gelt

Hanukkah gelt (Yiddish for "money") is often distributed to children to enhance their enjoyment of the holiday. The amount is usually in small coins, although grandparents or other relatives may give larger sums as an official Hanukkah gift. In Israel, Hanukkah gelt is known as dmei Hanukkah. Many Hasidic Rebbes distribute coins to those who visit them during Hanukkah. Hasidic Jews consider this to be an auspicious blessing from the Rebbe, and a segulah for success.

Rabbi Abraham P. Bloch has written that “The tradition of giving money (Chanukah gelt) to children is of long standing. The custom had its origin in the seventeenth-century practice of Polish Jewry to give money to their small children for distribution to their teachers. In time, as children demanded their due, money was also given to children to keep for themselves. Teen-age boys soon came in for their share. According to Magen Avraham (18th cent.), it was the custom for poor yeshiva students to visit homes of Jewish benefactors who dispensed Chanukah money (Orach Chaim 670). The rabbis approved of the custom of giving money on Chanukah because it publicized the story of the miracle of the oil.”[43]

Twentieth-century American chocolatiers picked up on the gift/coin concept by creating chocolate gelt.

Alternative spellings based on transliterating Hebrew letters

In Hebrew, the word Hanukkah is written חנֻכה or חנוכה (Ḥǎnukkâh). It is most commonly transliterated to English as Chanukah or Hanukkah, the former because the sound represented by "CH" ([χ], similar to the Scottish pronunciation of "loch") essentially does not exist in the modern English language. Furthermore, the letter "chet" (ח), which is the first letter in the Hebrew spelling, is pronounced differently in modern Hebrew (voiceless uvular fricative) than in classical Hebrew (voiceless pharyngeal fricative), and neither of those sounds is unambiguously representable in English spelling. Moreover, the 'kaf' consonant is geminate in classical (but not modern) Hebrew. Adapting the classical Hebrew pronunciation with the geminate and pharyngeal Ḥeth can lead to the spelling "Hanukkah"; while adapting the modern Hebrew pronunciation with no geminate and velar Ḥeth leads to the spelling "Chanukah".

Common variants

- Hanukkah (in North America and Australia, also common in UK)

- Chanukah (in the UK, also common in North America)

YIVO variant

- Khanike (YIVO standard transliteration from the Yiddish and/or Ashkenazic pronounced [ˈχanuka] of the Hebrew)

Background

Chronology

- 198 BCE: Armies of the Seleucid King Antiochus III (Antiochus the Great) oust Ptolemy V from Judea and Samaria.

- 175 BCE: Antiochus IV (Epiphanes) ascends the Seleucid throne.

- 168 BCE: Under the reign of Antiochus IV, the Temple is looted, Jews are massacred, and Judaism is outlawed.

- 167 BCE: Antiochus orders an altar to Zeus erected in the Temple. Mattathias, and his five sons John, Simon, Eleazar, Jonathan, and Judah lead a rebellion against Antiochus. Judah becomes known as Judah Maccabe (Judah The Hammer).

- 166 BCE: Mattathias dies, and Judah takes his place as leader. The Hasmonean Jewish Kingdom begins; It lasts until 63 BCE

- 165 BCE: The Jewish revolt against the Seleucid monarchy is successful. The Temple is liberated and rededicated (Hanukkah).

- 142 BCE: Establishment of the Second Jewish Commonwealth. The Seleucids recognize Jewish autonomy. The Seleucid kings have a formal overlordship, which the Hasmoneans acknowledged. This inaugurates a period of great geographical expansion, population growth, and religious, cultural and social development.

- 139 BCE: The Roman Senate recognizes Jewish autonomy.

- 130 BCE: Antiochus VII besieges Jerusalem, but withdraws.

- 131 BCE: Antiochus VII dies. The Hasmonean Jewish Kingdom throws off Syrian rule completely

- 96 BCE: An eight year civil war begins.

- 83 BCE: Consolidation of the Kingdom in territory east of the Jordan River.

- 63 BCE: The Hasmonean Jewish Kingdom comes to an end because of rivalry between the brothers Aristobulus II and Hyrcanus II, both of whom appeal to the Roman Republic to intervene and settle the power struggle on their behalf. The Roman general Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) is dispatched to the area. Twelve thousand Jews are massacred as Romans enter Jerusalem. The Priests of the Temple are struck down at the Altar. Rome annexes Judea.

Battles of the Maccabean revolt

There were a number of key battles between the Maccabees and the Seleucid Syrian-Greeks:

- Battle of Adasa (Judas Maccabeus leads the Jews to victory against the forces of Nicanor.)

- Battle of Beth Horon (Judas Maccabeus defeats the forces of Seron.)

- Battle of Beth-zechariah (Elazar the Maccabee is killed in battle. Lysias has success in battle against the Maccabess, but allows them temporary freedom of worship.)

- Battle of Beth Zur (Judas Maccabeus defeats the army of Lysias, recapturing Jerusalem.)

- Dathema (A Jewish fortress saved by Judas Maccabeus.)

- Battle of Elasa (Judas Maccabeus dies in battle against the army of King Demetrius and Bacchides. He is succeeded by Jonathan Maccabaeus and Simon Maccabaeus who continue to lead the Jews in battle.)

- Battle of Emmaus (Judas Maccabeus fights the forces of Lysias and Georgias).

- Battle of Wadi Haramia.

When Hanukkah occurs

The dates of Hanukkah are determined by the Hebrew calendar. Hanukkah begins at the 25th day of Kislev and concludes on the 2nd or 3rd day of Tevet (Kislev can have 29 or 30 days). The Jewish day begins at sunset, whereas the Gregorian calendar begins the day at midnight. So, the first day of Hanukkah actually begins at sunset of the day immediately before the date noted on Gregorian calendars.

According to the Gregorian calendar

Hanukkah begins at sundown on the evening before the date shown.

- December 12, 2009

- December 2, 2010

- December 21, 2011

- December 9, 2012

- November 28, 2013

- December 17, 2014

- December 7, 2015

- December 25, 2016

- December 13, 2017

- December 3, 2018

- December 23, 2019

- December 11, 2020

Hanukkah in the White House

The United States has a history of recognizing and celebrating Hanukkah in a number of ways, from menorah lighting ceremonies to a 1996 postage stamp, jointly issued with Israel, to special receptions in the White House.

One of the earliest links with the White House occurred in 1951, when Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion presented United States President Harry Truman with a Hanukkah Menorah. But it was not until 1979 that a sitting president, Jimmy Carter took part in a public Hanukkah candle-lighting ceremony on the National Mall, followed by the first Hanukkah candle-lighting ceremony in the White House itself, led by President Bill Clinton.

In 2001, President George W. Bush held an official Hanukkah reception in the White House in conjunction with the candle-lighting ceremony, and since then this ceremony has become an annual tradition attended by Jewish leaders from around the country. In 2008, George Bush linked the occasion to the 1951 gift by using that menorah for the ceremony, with a grandson of Ben-Gurion and a grandson of Truman lighting the candles.

Criticism of Hanukkah

Christopher Hitchens has referred to Hanukkah as a celebration of the "triumph of tribal Jewish backwardness" and an "explicit celebration of the original victory of bloody-minded faith over enlightenment and reason."[44]

See also

- County of Allegheny v. ACLU on the constitutionality of Hanukkah displays on public property in the U.S.

- Hanukkah bush

- Hasmonean kingdom

- Hellenistic Judaism

- Jewish holidays

References

- ↑ Gateway To The Holy Land: "Hanukkah." Retrieved on September 03, 2010

- ↑ Talmud Gittin 57b tells a story of a woman and her seven sons killed by "Caesar". The name "Hannah" is not stated.

- ↑ Maharsha Shabbat 21b; see there for a detailed discussion. (Hebrew textPDF)

- ↑ Scherman, Nosson. "Origin of the Name Chanukah". ArtScroll. http://innernet.org.il/article.php?aid=11.

- ↑ Ran Shabbat 9b (Hebrew textPDF)

- ↑ Yesod Hamishna Va'arichatah pp. 25–28 (Hebrew textPDF)

- ↑ Jewishvirtuallibrary.org

- ↑ Perseus.tufts.edu, Jewish Antiquities xii. 7, § 7, #323

- ↑ Zvieli, Benjamin. "The Scroll of Antiochus". http://www.biu.ac.il/JH/Parasha/eng/miketz/zev.html. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 The Scroll Of The Hasmoneans

- ↑ The Scroll of Antiochus and The Unknown Chanukah Megillah

- ↑ Old.perseus.tufts.edu Jewish War i. 31

- ↑ Old.perseus.tufts.edu, Jewish War i. 32

- ↑ Old.perseus.tufts.edu, Jewish War i. 34

- ↑ 1 Macc. iv. 59

- ↑ 1 Macc. iv. 36

- ↑ Macc. x. 6 and i. 9

- ↑ Telushkin, Joseph (1991). Jewish Literacy: The Most Important Things to Know about the Jewish Religion, Its People, and Its History. W. Morrow. p. 114. ISBN 0688085067.

- ↑ Johnston, Sarah Iles (2004). Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. Harvard University Press. p. 186. ISBN 0674015177.

- ↑ Greenberg, Irving (1993). The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays. Simon & Schuster. p. 29. ISBN 0671873032.

- ↑ Schultz, Joseph P. (1981). Judaism and the Gentile Faiths: Comparative Studies in Religion. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 155. ISBN 0838617077. "Modern scholarship on the other hand considers the Maccabean revolt less as an uprising against foreign oppresion than as a civil war between the orthodox and reformist parties in the Jewish camp"

- ↑ Gundry, Robert H. (2003). A Survey of the New Testament. Zondervan. p. 9. ISBN 0310238250.

- ↑ Grabbe, Lester L. (2000). Judaic Religion in the Second Temple Period: Belief and Practice from the Exile to Yavneh. Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 0415212502.

- ↑ Freedman, David Noel; Allen C. Myers, Astrid B. Beck (2000). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 837. ISBN 0802824005.

- ↑ Wood, Leon James (1986). A Survey of Israel's History. Zondervan. p. 357. ISBN 031034770X.

- ↑ Tchrikover, Victor. Hellenistic Civilization and the Jews.

- ↑ Shulkhan Arukh Orach Chayim 670:1

- ↑ Shulkhan Arukh Orach Chayim 671:2

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Shulkhan Arukh Orach Chayim 673:1

- ↑ Shulkhan Arukh Orach Chayim 676:1–2

- ↑ Shulkhan Arukh Orach Chayim 676:4

- ↑ Shulkhan Arukh Orach Chayim 682:1

- ↑ Rema on Shulkhan Arukh Orach Chayim 670:2

- ↑ Mishna Berurah 670:2:10

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud: Shabbat 23a

- ↑ Shalom Center on Hannukah and the environment

- ↑ Jerusalem Post: Green Hanukkia' campaign sparks ire

- ↑ Coalition on Environment and Jewish Life (COEJL): Green Hannukah ceremony

- ↑ Gur, Jana, The Book of New Israeli Food: A Culinary Journey, pp. 238–243, Schocken (2008) ISBN 0-8052-1224-8

- ↑ Hanukkah: Doughnuts go healthy., ynetnews.com

- ↑ Minsberg, Tali and Lidman, Melanie. Love Me Dough. Jerusalem Post, 10 December 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- ↑ Ohr Somayach :: Chanukah :: The Secret of the Dreidel

- ↑ The Biblical and Historical Background of Jewish Customs and Ceremonies by Abraham P. Bloch. Published by KTAV Publishing House, Inc., 1980. Pp. 277.

- ↑ Hitchens, Christopher (12-03-07). "Bah, Hanukkah". http://www.slate.com/id/2179045/. Retrieved 03-16-10.

External links

- Comprehensive Hanukkah Guide

- English translation of Megillas Antiochus

- Hanukkah songsheets

- Hanukkah songs

- Traditional Hanukkah recipes

- About Kosher Hanukkah recipes

- Wiki-Recipe.org Hanukkah recipes

- Video: How to light the Hanukkah menorah

- The Grand Rabbi of Satmar lighting the Hanukkah Menorah

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||