Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (also known as the Hanse or Hansa) was an economic alliance of trading cities and their guilds that established and maintained a trade monopoly along the coast of Northern Europe. It stretched from the Baltic to the North Sea and inland, during the Late Middle Ages and early modern period (c.13th–17th centuries). The Hanseatic cities had their own law system and furnished their own protection and mutual aid, thus having a sort of a political autonomy and in some cases creating political entities of their own.

Contents |

History

Historians generally trace the origins of the League to the rebuilding of the North German town of Lübeck in 1159 by Duke Henry the Lion of Saxony, after Henry had captured the area from Count Adolf II of Holstein.

Exploratory trading adventures, raids and piracy had happened earlier throughout the Baltic (see Vikings)—the sailors of Gotland sailed up rivers as far away as Novgorod, for example—but the scale of international trade economy in the Baltic area remained insignificant before the growth of the Hanseatic League.

German cities achieved domination of trade in the Baltic with striking speed over the next (i.e. 13th) century, and Lübeck became a central node in all the seaborne trade that linked the areas around the North Sea and the Baltic Sea. The 15th century saw the climax of Lübeck's hegemony.

Foundation and formation

Lübeck became a base for merchants from Saxony and Westphalia to spread east and north. Well before the term Hanse appeared in a document (1267), merchants in a given city began to form guilds or Hansa with the intention of trading with towns overseas, especially in the less-developed eastern Baltic area, a source of timber, wax, amber, resins, furs, even rye and wheat brought down on barges from the hinterland to port markets. The towns furnished their own protection armies and each guild had to furnish a number of members into service, when needed. The trade ships often had to be used to carry soldiers and their arms. The Hanseatic cities came to each other's aid.

Visby functioned as the leading centre in the Baltic before the Hansa. Sailing east, Visby merchants established a branch at Novgorod. To begin with they used the Gotlandic Gutagard. With the influx of too many merchants, the Gotlanders arranged their own trading stations for the Peterhof further up from the river.[1] Before the foundation of the Hanseatic league in 1356 the word Hanse did not occur in the Baltic. The Gotlanders used the word varjag.

Hansa societies worked to remove restrictions to trade for their members. For example, the merchants of the Cologne Hansa convinced Henry II of England to free them (1157) from all tolls in London and allow them to trade at fairs throughout England. The "Queen of the Hansa", Lübeck, where traders were required to trans-ship goods between the North Sea and the Baltic, gained the Imperial privilege of becoming a Free imperial city in 1227, the only such city east of the River Elbe.

In 1241, Lübeck, which had access to the Baltic and North Sea fishing grounds, formed an alliance — a foundation of the League — with Hamburg, another trading city, which controlled access to salt-trade routes from Lüneburg. The allied cities gained control over most of the salt-fish trade, especially the Scania Market; and Cologne joined them in the Diet of 1260. In 1266, Henry III of England granted the Lübeck and Hamburg Hansa a charter for operations in England, and the Cologne Hansa joined them in 1282 to form the most powerful Hanseatic colony in London. Much of the drive for this co-operation came from the fragmented nature of existing territorial government, which failed to provide security for trade. Over the next 50 years the Hansa itself emerged with formal agreements for confederation and co-operation covering the west and east trade routes. The chief city and linchpin remained Lübeck; with the first general Diet of the Hansa held there in 1356, the Hanseatic League acquired an official structure.[2]

Expansion

Lübeck's location on the Baltic provided access for trade with Scandinavia and Kiev Rus, putting it in direct competition with the Scandinavians who had previously controlled most of the Baltic trade routes. A treaty with the Visby Hansa put an end to competition: through this treaty the Lübeck merchants also gained access to the inland Russian port of Novgorod, where they built a trading post or Kontor. Other such alliances formed throughout the Holy Roman Empire. Yet the League never became a closely-managed formal organisation. Assemblies of the Hanseatic towns met irregularly in Lübeck for a Hansetag (‘Hanseatic Day’), from 1356 onwards, but many towns chose not to send representatives and decisions were not binding on individual cities. Over time, the network of alliances grew to include a flexible roster of 70 to 170 cities.[3]

The league succeeded in establishing additional Kontors in Bruges (Flanders), Bergen (Norway), and London (Kingdom of England). These trading posts became significant enclaves. The London Kontor, established in 1320, stood west of London Bridge near Upper Thames Street. (Cannon Street station occupies the site now[update].) It grew significantly over time into a walled community with its own warehouses, weighhouse, church, offices and houses, reflecting the importance and scale of the activity carried on. The first reference to it as the Steelyard (der Stahlhof) occurs in 1422.

In addition to the major Kontors, individual Hanseatic ports had a representative merchant and warehouse. In England this happened in Boston, Bristol, Bishop's Lynn (now King's Lynn, which features the sole remaining Hanseatic warehouse in England), Hull, Ipswich, Norwich, Yarmouth (now Great Yarmouth), and York.

The League primarily traded timber, furs, resin (or tar), flax, honey, wheat, and rye from the east to Flanders and England with cloth (and, increasingly, manufactured goods) going in the other direction. Metal ore (principally copper and iron) and herring came southwards from Sweden.

German colonists in the 12th and 13th centuries settled in numerous cities on and near the east Baltic coast, such as Elbing (Elbląg), Thorn (Toruń), Reval (Tallinn), Riga, and Dorpat (Tartu), which became members of the Hanseatic League, and some of which still retain many Hansa buildings and bear the style of their Hanseatic days. Most were granted Lübeck law (Lübisches Recht), which provided that they had to appeal in all legal matters to Lübeck's city council. The Livonian Confederation incorporated parts of modern-day Estonia and Latvia and had its own Hanseatic parliament (diet); all of its major towns became members of the Hanseatic League. The dominant language of trade was Middle Low German, a dialect with significant impact for countries involved in the trade, particularly the larger Scandinavian languages.

Zenith

The League had a fluid structure, but its members shared some characteristics. First, most of the Hansa cities either started as independent cities or gained independence through the collective bargaining power of the League, though such independence remained limited. The Hanseatic free imperial cities owed allegiance directly to the Holy Roman Emperor, without any intermediate tie to the local nobility.

Another similarity involved the cities' strategic locations along trade routes. At the height of its power in the late 1300s, the merchants of the Hanseatic League succeeded in using their economic clout and sometimes their military might—trade routes needed protecting and the League's ships sailed well-armed—to influence imperial policy.

The League also wielded power abroad. Between 1361 and 1370, the League waged war against Denmark. Initially unsuccessful, Hanseatic towns in 1368 allied in the Confederation of Cologne, sacked Copenhagen and Helsingborg, and forced King Valdemar IV of Denmark and his son-in-law Hakon VI of Norway to grant the League 15% of the profits from Danish trade in the subsequent peace-treaty of Stralsund in 1370, thus gaining an effective trade and political monopoly in Scandinavia. This favourable treaty was the high-water mark of Hanseatic power. The commercial privileges were renewed in the Treaty of Vordingborg, 1435.[4][5][6]

The Hansa also waged a vigorous campaign against pirates. Between 1392 and 1440, maritime trade of the League faced danger from raids of the Victual Brothers and their descendants, privateers hired in 1392 by Albert of Mecklenburg against the Queen Margaret I of Denmark. In the Dutch-Hanseatic War (1438—41), the merchants of Amsterdam sought and eventually won free access to the Baltic and broke the Hansa monopoly. As an essential part of protecting their investment in trade and ships, the League trained pilots and erected lighthouses.

Exclusive trade routes often came at a high price. Most foreign cities confined the Hansa traders to certain trading areas and to their own trading posts. They could seldom, if ever, interact with the local inhabitants, except in the matter of actual negotiation. Moreover, many people, merchant and noble alike, envied the power of the League. For example, in London the local merchants exerted continuing pressure for the revocation of the privileges of the League. The refusal of the Hansa to offer reciprocal arrangements to their English counterparts exacerbated the tension. King Edward IV of England reconfirmed the league's privileges in the Treaty of Utrecht (1474) despite this hostility, in part thanks to the significant financial contribution the League made to the Yorkist side during The Wars of the Roses. A century later, in 1597, Queen Elizabeth I of England expelled the League from London and the Steelyard closed the following year. The very existence of the League and its privileges and monopolies created economic and social tensions that often crept over into rivalry between League members.

Rise of rival powers

The economic crises of the late 14th century did not spare the Hansa. Nevertheless, its eventual rivals emerged in the form of the territorial states, whether new or revived, and not just in the west: Poland triumphed over the Teutonic Knights in 1466; Ivan III of Russia ended the entrepreneurial independence of Hansa's Novgorod kantor in 1478. New vehicles of credit imported from Italy outpaced the Hansa economy, in which silver coin changed hands rather than bills of exchange.

In the 14th century, tensions between Prussian region and the "Wendish" cities (Lübeck and eastern neighbours) increased. Lübeck was dependent on its role as centre of the Hansa, being on the shore of the sea without a major river. It was on the entrance of the land route to Hamburg, but this land route could be bypassed by sea travel around Denmark and through the Sound. Prussia's main interest, on the other hand, was primarily the export of bulk products like grain and timber, which were very important for England, the Low Countries, and later on also for Spain and Italy.

In 1454, the year of Elisabeth Habsburg's marriage to the Jagiellonian king, the towns of the Prussian Confederation rose against the dominance of the Teutonic Order and asked king Casimir IV of Poland for help. Danzig, Thorn, and Elbing became part of the Kingdom of Poland, (1466–1569 referred to as Royal Prussia) by the Second Peace of Thorn (1466). Polish-Lithuania in turn was heavily supported by the Holy Roman Empire through family connections and by military assistance under the Habsburgs. Kraków, then the capital of Poland, was also a Hansa city with German burghers around 1500. The lack of customs borders on the River Vistula after 1466 helped to gradually increase Polish grain export, transported to the sea down the Vistula, from 10,000 tonnes per year in the late 15th century to over 200,000 tonnes in the 17th century.[7] The Hansa-dominated maritime grain trade made Poland one of the main areas of its activity, helping Danzig to become the Hansa's largest city.

The member cities took responsibility for their own protection. In 1567 a Hanseatic League Agreement reconfirmed previous obligations and rights of League members, such as common protection and defense against enemies.[8] The Prussian Quartier cities of Thorn, Elbing, Königsberg and Riga and Dorpat also signed. When pressed by the king of Poland-Lithuania, Danzig remained neutral and would not allow ships running for Poland into its territory. They had to anchor somewhere else, such as at Pautzke (now Puck, Poland).

A major benefit for the Hansa was its control of the shipbuilding market, mainly in Lübeck and in Danzig. The Hansa sold ships everywhere in Europe, including Italy. They drove out the Dutch, because Holland wanted to favour Bruges as a huge staple market at the end of a trade route. When the Dutch started to become competitors of the Hansa in shipbuilding, the Hansa tried to stop the flow of shipbuilding technology from Hansa towns to Holland. Danzig, a trading partner of Amsterdam, tried to stall the decision. Dutch ships sailed to Danzig to take grain from the city directly, to the dismay of Lübeck. Hollanders also circumvented the Hansa towns by trading directly with North German princes in non-Hansa towns. Dutch freight costs were much lower than those of the Hansa, and the Hansa were excluded as middlemen.

When Bruges, Antwerp and Holland all became part of the same country, the Duchy of Burgundy, they actively tried to take over the monopoly of trade from the Hansa, and the staple market from Bruges was moved to Amsterdam. The Dutch merchants aggressively challenged the Hansa and met with much success. Hanseatic cities in Prussia, Livonia supported the Dutch against the core cities of the Hansa in northern Germany. After several naval wars between Burgundy and the Hanseatic fleets, Amsterdam gained the position of leading port for Polish and Baltic grain from the late 15th century onwards. The Dutch regarded Amsterdam's grain trade as the mother of all trades (Moedernegotie). Denmark and England tried to destroy the Netherlands in the First Navigation War (1652–1654).[9] The war ended in a truce, but the Anglo-Dutch rivalry continued.[9] A Second Dutch Navigation War (1665–1667) broke out which also ended inconclusively.[10] Later, there was a Third Navigation War (1672–1674), which also resulted in another failed attempt to destroy Holland.[11]

Nuremberg in Franconia developed an overland route to sell formerly Hansa-monopolized products from Frankfurt via Nuremberg and Leipzig to Poland and Russia, trading Flemish cloth and French wine in exchange for grain and furs from the east. The Hansa profited from the Nuremberg trade by allowing Nurembergers to settle in Hansa towns, which the Franconians exploited by taking over trade with Sweden as well. The Nuremberger merchant Albrecht Moldenhauer was influential in developing the trade with Sweden and Norway, and his sons Wolf and Burghard established themselves in Bergen and Stockholm, becoming leaders of the Hanseatic activities locally.

End of the Hansa

At the start of the 16th century the League found itself in a weaker position than it had known for many years. The rising Swedish Empire had taken control of much of the Baltic. Denmark had regained control over its own trade, the Kontor in Novgorod had closed, and the Kontor in Bruges had become effectively defunct. The individual cities which made up the League had also started to put self-interest before their common Hansa interests. Finally the political authority of the German princes had started to grow—and so constrain the independence of action which the merchants and Hanseatic towns had enjoyed.

The League attempted to deal with some of these issues. It created the post of Syndic in 1556 and elected Heinrich Sudermann as a permanent official with legal training, who worked to protect and extend the diplomatic agreements of the member towns. In 1557 and 1579 revised agreements spelled out the duties of towns and some progress was made. The Bruges Kontor moved to Antwerp and the Hansa attempted to pioneer new routes. However, the League proved unable to halt the progress around it and so a long decline commenced. The Antwerp Kontor closed in 1593, followed by the London Kontor in 1598. The Bergen Kontor continued until 1754; its buildings alone of all the Kontoren survive (see Bryggen).

The gigantic Adler von Lübeck warship, which was constructed for military use against Sweden during the Northern Seven Years' War (1563–70), but never put to military use, epitomized the vain attempts of Lübeck to uphold its long-privileged commercial position in a changed economic and political climate.

By the late 16th century the League had imploded and could no longer deal with its own internal struggles, the social and political changes that accompanied the Protestant Reformation, the rise of Dutch and English merchants, and the incursion of the Ottoman Empire upon its trade routes and upon the Holy Roman Empire itself. Only nine members attended the last formal meeting in 1669 and only three (Lübeck, Hamburg and Bremen) remained as members until its final demise in 1862.

Despite its collapse, several cities still maintain the link to the Hanseatic League today[update]. The Dutch cities of Deventer, Kampen, Zutphen, and the nine German cities Bremen, Demmin, Greifswald, Hamburg, Lübeck, Lüneburg, Rostock, Stralsund and Wismar still call themselves Hanse cities. Lübeck, Hamburg, and Bremen continue to style themselves officially as "Free (and) Hanseatic Cities." (Rostock's football team is named F.C. Hansa Rostock in memory of the city's trading past.) For Lübeck in particular, this anachronistic tie to a glorious past remained especially important in the 20th century. In 1937 the Nazi Party removed this privilege through the Greater Hamburg Act after the Senat of Lübeck did not permit Adolf Hitler to speak in Lübeck during his election campaign.[12] He held the speech in Bad Schwartau, a small village on the outskirts of Lübeck. Subsequently, he referred to Lübeck as "the small city close to Bad Schwartau." After the EU enlargement to the East in May 2004 there are some experts who wrote about the resurrection of the Baltic Hansa [13].

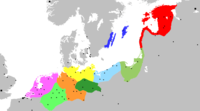

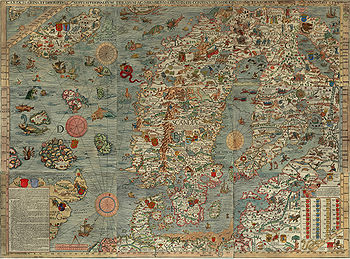

Historical maps

Europe in 1097 |

The Baltic region in 1219 (German coast occupied by Denmark, before the Battle of Bornhöved (1227) |

Europe in 1328 |

Europe in 1430 |

Europe in 1470 |

Carta marina of the Baltic Sea region (1539) |

The Baltic region in 1646 (Treaty of Brömsebro) |

The Baltic region in 1658 (Treaty of Roskilde) |

The Baltic region in 1814 (Congress of Vienna) |

Lists of former Hansa cities

Members of the Hanseatic League

Wendish Circle

- Lübeck (chief city)

- Greifswald

- Hamburg

- Kiel

- Lüneburg

- Rostock

- Stade

- Stettin (Szczecin)

- Stralsund

- Wismar

Saxony, Thuringia, Brandenburg Circle

|

|

Prussia, Livonia, Sweden Circle

- Breslau (now Wrocław)

- Kulm (now Chełmno)

- Danzig (now Gdańsk, chief city)

- Dorpat (now Tartu)

- Elbing (now Elbląg)

- Fellin (now Viljandi)

- Kraków

- Goldingen (now Kuldīga)

- Kokenhusen (now Koknese)

- Königsberg (now Kaliningrad)

- Lemsal (now Limbaži)

- Pernau (now Pärnu)

- Reval (now Tallinn)

- Riga (now Rīga, chief city)

- Roop (now Straupe)

- Thorn (now Toruń)

- Visby

- Wenden (now Cēsis)

- Windau (now Ventspils)

- Wolmar (now Valmiera)

Rhine, Westphalia, the Netherlands Circle

- Duisburg

- Zwolle

- Haltern am See

- Hattem

- Hasselt

- Hattingen

- Cologne

- Dortmund (chief city)

- Soest

- Geseke

- Osnabrück

- Münster

- Coesfeld

- Roermond

- Nijmegen

- Tiel

- Deventer, with subsidiary cities:

- Groningen

- Kampen

- Bochum

- Recklinghausen

- Hamm

- Unna

- Werl

- Zutphen

- Breckerfeld

- Minden

Counting houses

Principal Kontore

Subsidiary Kontore

- Antwerp

- Berwick upon Tweed

- Boston

- Damme

- Leith

- Hull

- Ipswich

- King's Lynn

- Kaunas

- Newcastle

- Polotsk

- Pskov

- Great Yarmouth

- York

Other cities with a Hansa community

Modern "City League The HANSE"

In 1980, former Hanseatic League members established a "new Hanse" in Zwolle, the "City League The HANSE". This league is open to all former Hanseatic League members and cities that once hosted a Hanseatic kontor. The latter include twelve Russian cities, most notably Novgorod, which was a major Russian trade partner of the Hansa in the Middle Ages. The "new Hanse" fosters and develops business links, tourism and cultural exchange.[14]

The headquarters of the New Hansa is in Lübeck, Germany. The current President of the Hanseatic League of New Time is Bernd Saxe, Mayor of Lübeck.[14]

Each year one of the member cities of the New Hansa hosts the Hanseatic Days of New Time international festival.

Three years ago King's Lynn became the only English member of the newly formed modern Hanseatic League.

Fictional references

- A Terran Hanseatic League exists in Kevin J. Anderson's science fiction series, Saga of Seven Suns. The political structure of this fictional interstellar version closely resembles that of the historical Hanseatic League.

- In the computer game series Patrician players begin as a trader and work their way to the head of the Hanseatic League.

- The PC game Patrician III: Rise of the Hanse is a simulation of trade amongst member cities of the Hanseatic League beginning in the 14th century.

- In the computer game Darklands players can accept smaller missions from Hanseatic traders.

- In the Perry Rhodan SF series, the trade organisation the Cosmic Hansa (Kosmische Hanse) covers the Galaxy. The English translation for this organisation is Cosmic House (see American issues 1800-1803) as it was felt that no one would understand the Hanseatic League reference.

- Midgard open source content management system has often been referred to as the Hanseatic League of Open Source.

- In the Battletech tabletop and roleplaying universe, there is a state in the Deep Periphery (towards the center of the Galaxy, measured from Earth) called the Hanseatic League, which is structured as a plutocratic trade empire, but which has considerably more primitive social and technological structures when compared to human societies closer to Earth.

- Hanseatic League merchant caravans are used as the backdrop for "living history" groups in Florida and North Carolina. Hanseatic League Historical Re-enactors has two chapters, Bergens Kontor in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and Voss Kontor in Fayetteville, North Carolina. Both groups portray merchants from a Hanseatic League merchant caravan originating from kontors and towns in Norway. They offer "in character" lectures, skits and "theatre in the round", based on the history of the Hanseatic League, for the education and entertainment of Renaissance Festival patrons and local schools.

- Robert A. Heinlein's novel, Citizen of the Galaxy, revolves around a loose league of trading spaceships of varying old Earth nationalities like the Finns aboard the "Sisu." Another ship is called "Hansea."

- Arthur Rimbaud mentions the Hansa merchant ships in his poem, Le Bateau ivre:

-

- ...moi, bateau perdu sous les cheveux des anses,

- Jeté par l'ouragan dans l'éther sans oiseau,

- Moi dont les Monitors et les voiliers des Hanses

- N'auraient pas repêché la carcasse ivre d'eau ;

- In the book Metro 2033 by Dmitry Glukhovsky, the Hanseatic League is an organisation of traders that controls the radial of the fictional future Moscow Metro. They regulate and facilitate trade around the Metro.

See also

- Company of Merchant Adventurers of London

- Hanseatic Cross

- Hanseatic Days of New Time

- Hanseatic flags

- List of ships of the Hanseatic League

- Lufthansa

- Naval history

- Thalassocracy

References

Notes

- ↑ Translation of the grant of privileges to merchants in 1229: "Medieval Sourcebook: Privileges Granted to German Merchants at Novgorod, 1229". Fordham.edu. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1229novgorod-germans.html. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ↑ Atatüre, Süha (2008). "The Historical Roots of European Union: Integration, Characteristics, and Responsibilities for the 21st Century". European Journal of Social Sciences (eurojournal) (2, vol 7). http://www.eurojournals.com/ejss_7_2_02.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ↑ Fernand Braudel: The Perspective of the World. Vol III of Civilisation and Capitalism 1984

- ↑ Phillip Pulsiano, Kirsten Wolf, Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia, Taylor & Francis, 1993, p.265, ISBN 0824047877

- ↑ Peter N. Stearns, William Leonard Langer, The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Arranged, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001, p.265, ISBN 0395652375

- ↑ Angus MacKay, David Ditchburn, Atlas of Medieval Europe, Routledge, 1997, p.171, ISBN 0415019230

- ↑ Norman Davies God's playground. A history of Poland, Columbia University Press, 1982

- ↑ "Agreement of the Hanseatic League at Lübeck, 1557". Balticconnections.net. http://www.balticconnections.net/views/exhibition/detail.cfm?mode=language&ID=18CEDA3F-D929-4A8E-E777F313AC7EB8E4. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Willson, David Harris (1972). A History of England. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. p. 401.

- ↑ Willson, David Harris (1972). A History of England. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. p. 411.

- ↑ Willson, David Harris (1972). A History of England. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. p. 414.

- ↑ Europe a la Carte. "Guide to Lubeck". Europealacarte.co.uk. http://www.europealacarte.co.uk/Germany/lubeck.html. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ↑ Travel to the Baltic Hansa EuropaRussia, books

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Website City League The HANSE

Bibliography

- Dollinger, P. The German Hansa (1970; repr.1999).

- Nash, E. Gee. The Hansa. 1929 (Reprint. 1995 Edition, Barnes and Noble)

- Giuseppe D'Amato, Viaggio nell'Hansa baltica, l'Unione europea e l'allargamento ad Est (Travel to the Baltic Hansa, the European Union and its enlargement to the East). Greco&Greco, Milano, 2004. ISBN 88-7980-355-7

External links

- 29th International Hansa Days in Novgorod

- 30th Int'l Hansa Days 2010 in Parnu-Estonia

- NPG Social & Cultural Struggle for an Hanseatic Revival

- Chronology

- Hanseatic Cities in The Netherlands

- Hanseatic League Historical Re-enactors

- Hanseatic Towns Network

- Hanseatic League related sources in the German Wikisource

- Colchester a Hanseatic port – Gresham

- The Lost Port of Sutton: Maritime trade

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||