Aleppo

| Aleppo حلب |

|

|---|---|

| Aleppo City landmarks

|

|

| Nickname(s): Al-Shahbaa | |

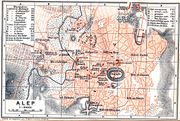

Aleppo

|

|

| Coordinates: | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Aleppo Governorate |

| District | Jabal Semaan |

| Government | |

| - Head of City Council | Ma'an Al-Shibli |

| Area | |

| - City | 190 km2 (73.4 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 379 m (1,243 ft) |

| Population (2004 census) | |

| - City | 2,181,061 |

| - Metro | 2,490,751 |

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) |

| - Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) |

| Area code(s) | Country code: 963, City code: 21 |

| Demonym | Aleppine |

| Website | Aleppo City |

| Sources: Aleppo city area [1] Sources: Aleppo city and metro population [2] | |

Aleppo (Arabic: حلب [ˈħalab], other names), located in northern Syria, is the largest Syrian city and the most populous in the Levant,[3] with a population of 2,181,061 (2004 official census) and the capital of the Aleppo Governorate, the most populous Syrian Governorate with a population of more than 4,507,000 (2009 estimate).[4]

Aleppo is one of the oldest inhabited cities in the world; it has known human settlement for at least 4,000 years (since at least the second millennium B.C.). This has been proved through the residential houses that were discovered in Tel Qaramel.[5] Such a long history is probably due its being a strategic trading point midway between the Mediterranean Sea and the Euphrates. Initially, Aleppo was built on a small group of hills surrounding the prominent hill where the castle was erected.[6] The river Quwēq (قويق) runs through the city.

For centuries, Aleppo has been Greater Syria's largest city, and in the 19th century it was the Ottoman Empire's third, after Constantinople and Cairo. Although relatively close to Damascus in distance, Aleppo is distinct in identity, architecture and culture, all shaped by a markedly different history and geography.

The city's significance in history has been its location at the end of the Silk Road, which passed through central Asia and Mesopotamia. When the Suez Canal was inaugurated in 1869, trade was diverted to sea and Aleppo began its slow decline. At the fall of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, Aleppo ceded its northern hinterland to modern Turkey, as well as the important railway connecting it to Mosul. Then in the 1940s it lost its main access to the sea, Antioch and Alexandretta (Iskenderun), also to Turkey. Finally, the isolation of Syria in the past few decades further exacerbated the situation, although perhaps it is this very decline that has helped to preserve the old city of Aleppo, its mediaeval architecture and traditional heritage. Aleppo is now experiencing a noticeable revival and is slowly returning to the spotlight. It recently won the title of the "Islamic Capital of Culture 2006", and has also witnessed a wave of successful restorations of its treasured monuments.

Etymology

Aleppo was known to antiquity as Khalpe, Khalibon, and to the Greeks as Beroea (Βέροια). During the Crusades, and again during the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, the name Alep was used: "Aleppo" is an Italianised version of this. However, the ancient name of the city, Halab, is of obscure origin. Some have proposed that Halab means 'iron' or 'copper' in Amorite languages since it was a major source of these metals in antiquity. Halaba in Aramaic means white, referring to the color of soil and marble abundant in the area. Another proposed etymology is that the name Halab means "gave out milk," coming from the ancient tradition that Abraham gave milk to travelers as they moved throughout the region.[7] The colour of his cows was ashen (Arab. shaheb); therefore the city is also called Halab ash-Shahba ("he milked the ash-coloured").

History

| Ancient City of Aleppo* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|

|

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv |

| Reference | 21 |

| Region** | List of World Heritage Sites in the Arab States |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1986 (10th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. |

|

Ancient history

Aleppo has scarcely been touched by archaeologists, since the modern city occupies its ancient site. The site has been occupied from around 5000 BC, as excavations in Tallet Alsauda show.

Early Bronze Age

In the third mellenium BCE, Aleppo was the capital of an independent kingdom closely related to Ebla, known as Armi to Ebla and Arman to the Akkadians. Giovanni Pettinato describes Armi as Ebla's alter ego. Naram-sin of Akkad (or his grandfather Sargon) destroyed both Ebla and Arman in the 23rd century BCE.[8][9]

Middle Bronze Age

In the Old Babylonian period Aleppo's name appears as Ḥalab (Ḥalba) for the first time.[9] Aleppo was the capital of the important Amorite dyansty of Yamḥad. The kingdom of Yamḥad, alternativley known as the 'land of Ḥalab,' was the most powerful in the Near East at the time.[10]

Yamḥad was destroyed by the Hittites under Mursilis I in the 16th century BCE. However, Aleppo soon resumed its leading role in Syria when the Hittite power in the region waned due to internal strife.[9]

Late Bronze Age

Taking advantage of the power vacuum in the region, Parshatatar, king of the Hurrian kingdom of Mittani, conquered Aleppo in the 15th century BCE. Subsequently, Aleppo found itself on the frontline in the struggle between Egypt and Mittani and the Hittites and Mittani.[9]

Hittite Suppiluliumas I permanently defeated Mittani and conquered Aleppo in the 14th century BCE. Aleppo had cultic importance to the Hittites for being the center of worship of the Storm-God.[9]

Iron Age

When the Hittite kingdom collapsed in the 12th century BCE, Aleppo bacame part of the Aramaic Syro-Hittite kingdom of Arpad (Bit Agusi), and later it became capital of the Aramaic Syro-Hittite kingdom of Hatarikka-Luhuti.

In the 9th century BCE Aleppo probably became part of the Neo-Assyrian empire, before passing through the hands of the Neo-Babylonians and the Achamenid Persians.

Classical Antiquity

Alexander the Great took over the city in 333 BC. Seleucus Nicator established a Hellenic settlement in the site between 301 BCE and 286 BCE. He called it Beroea, after Beroea in Macedon.

Northern Syria was the center of gravity of the Hellenistic colonizing activity, and therefore of Hellenistic culture in the Seleucid Empire. As did other Hellenized cities of the Seleucid kingdom, Beroea probably enjoyed a measure of local autonomy, with a local civic assembly or boulē composed of free Hellenes.[11]

Beroea remained under Seleucid rule for nearly 300 years until the last holdings of the Seleucid dynasty were handed over to Pompey in 64 BCE, at which time they became a Roman provice. Rome's presence afforded relative stability in northern Syria for over three centuries. Although the province was administered by a legate from Rome, Rome did not impose its administrative organization on the Greek-speaking ruling class.[11]

The Roman era saw increase in the population of northern Syria that accelerated under the Byzantines well into the 5th century. In Late Antiquity, Beroea was the second largest Syrian city after Antioch, the capital of Syria and the third largest city in the Roman world. Beroea was the main city of the Chalcidike region, and it was a bishopric in Coele Syria. Archaeological evidence indicates a high population density for settlements between Antioch and Beroea right up to the 6th century CE. This agrarian landscape holds now the remains of large estate houses and churches such as the Church of Saint Simeon Stylites.[11] Saint Maron of the Maronite Church was probably born in this region; his tomb is located at Brad to the west of Aleppo.

Beroea is mentioned in 2 Macc. 13:3.

Medieval period

The Sassanid Persians invaded Syria briefely in the early 7th century. Soon after Aleppo fell to Arabs under Khalid ibn al-Walid in 637. In 944, it became the seat of an independent Emirate under the Hamdanid prince Sayf al-Daula, and enjoyed a period of great prosperity, being home to the great poet al-Mutanabbi and the philosopher and polymath al-Farabi. The city was sacked by a resurgent Byzantine Empire in 962, while Byzantine forces occupied it briefly from 974 to 987. The city and its Emirate became an Imperial vassal from 969 until the Byzantine-Seljuk Wars. The city was twice besieged by the Crusaders, in 1098 and in 1124, but was not conquered.

On 9 August 1138, a deadly earthquake ravaged the city and the surrounding area. Although estimates from this time are very unreliable, it is believed that 230,000 people died, making it the fifth deadliest earthquake in recorded history.

The city came under the control of Saladin and then the Ayyubid Dynasty from 1183.

On 24 January 1260,[12] the city was taken by the Mongols under Hulagu in alliance with their vassals the Frank knights of the ruler of Antioch Bohemond VI and his father-in-law the Armenian ruler Hetoum I.[13] The city was poorly defended by Turanshah, and as a result the walls fell after six days of bombardment, and the citadel fell four weeks later. The Muslim population was massacred, though the Christians were spared. Turanshah was shown unusual respect by the Mongols, and was allowed to live because of his age and bravery. The city was then given to the former Emir of Hims, al-Ashraf, and a Mongol garrison was established in the city. Some of the spoils were also given to Hethoum I for his assistance in the attack. The Mongol Army then continued on to Damascus, which surrendered, and the Mongols entered the city on 1 March 1260.

In September 1260, the Egyptian Mamluks negotiated for a treaty with the Franks of Acre which allowed them to pass through Crusader territory unmolested, and engaged the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut on September 3, 1260. The Mamluks won a decisive victory, killing the Mongols' Nestorian Christian general Kitbuqa, and five days later they had re-taken Damascus. Aleppo was recovered by the Muslims within a month, and a Mamluk governor placed to govern the city. Hulagu sent troops to try and recover Aleppo in December. They were able to massacre a large number of Muslims in retaliation for the death of Kitbuqa, but after a fortnight could make no other progress and had to retreat.[14]

The Mamluk governor of the city became insubordinate to the central Mamluk authority in Cairo, and in Autumn 1261 the Mamluk leader Baibars send an army to reclaim the city. In October 1271, the Mongols took the city again, attacking with 10,000 horsemen from Anatolia, and defeating the Turcoman troops who were defending Aleppo. The Mamluk garrisons fled to Hama, until Baibars came north again with his main army, and the Mongols retreated.[15]

On 20 October 1280, the Mongols took the city again, pillaging the markets and burning the mosques. The Muslim inhabitants fled for Damascus, where the Mamluk leader Qalawun assembled his forces. When his army advanced, the Mongols again retreated, back across the Euphrates. Aleppo returned to native control in 1317. All Muslims returned back to Aleppo, but on the other hand, Christians who left the city during the Mongol invasion, were unable to resettle back in their own quarter in the old town, a fact that led them to establish a new district in the northern suburb of Aleppo outside the city walls. This new quarter was called Al-Jdeydeh ("the new district" in Arabic).

In 1400, the Mongol-Turkic leader Tamerlane captured the city again from the Mamluks.[16] He massacred many of the inhabitants, ordering the building of a tower of 20,000 skulls outside the city.[17]

Ottoman period

Aleppo became part of the Ottoman Empire in 1516, when the city had around 50,000 inhabitants. It was the center of the Vilayet of Aleppo and the capital of Syria.[18]

Thanks to its strategic geographic location on the trade route between Anatolia and the east, Aleppo rose to high prominence in the Ottoman era, at one point being second only to Constantinople in the empire. However, the economy of Aleppo was badly hit by the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, and since then Damascus rose as a serious competitor with Aleppo over the title of the capital of Syria.

Reference is made to the city in 1606 in William Shakespeare's 'Macbeth.' The witches torment the captain of the ship the Tiger which was headed to Aleppo from England but endured a 567 day voyage before returning unsuccessfully to port. Reference is also made to the city in Shakespeare's 'Othello' when Othello speaks his final words (ACT V, ii, 349f.): "Set you down this/And say besides that in Aleppo once,/Where a malignant and a turbanned Turk/Beat a Venitia and traduced the state,/I took by th' throat the circumcised dog/And smote him--thus!" (Arden Shakespeare Edition, 2004). The English naval chaplain Henry Teonge describes in his diary a visit he paid to the city in 1675, when there was a colony of West European merchants living there.

The city remained Ottoman until the empire's collapse, but was occasionally riven with internal feuds as well as attacks of the plague and later cholera from 1823. By 1901 its population was around 125,000.

At the end of World War I, the Treaty of Sèvres made most of the Province of Aleppo part of the newly established nation of Syria, while Cilicia was promised by France to become an Armenian state. However, Kemal Ataturk annexed most of the Province of Aleppo as well as Cilicia to Turkey in his War of Independence. The Arab residents in the province (as well as the Kurds) supported the Turks in this war against the French, a notable example being Ibrahim Hanano who directly coordinated with Ataturk and received weaponry from him. The outcome, however, was disastrous for Aleppo, because as per the Treaty of Lausanne, most of the Province of Aleppo was made part of Turkey with the exception of Aleppo and Alexandretta; thus, Aleppo was cut from its northern satellites and from the Anatolian cities beyond on which Aleppo depended heavily in commerce. Moreover, the Sykes-Picot division of the Near East separated Aleppo from most of Mesopotamia, which also harmed the economy of Aleppo. The situation exacerbated further in 1939 when Alexandretta was annexed to Turkey, thus depriving Aleppo from its main port of Iskenderun and leaving it in total isolation within Syria.

French mandate

The State of Aleppo was declared by the French General Henri Gouraud in September 1920 as part of a French scheme to make Syria easier to control by dividing it into several smaller states. France became more hostile to the idea of a united Syria after the Battle of Maysaloun.

By separating Aleppo from Damascus, Gouraud wanted to capitalize on a traditional state of competition between the two cities and turn it into political division. The people in Aleppo were unhappy with the fact that Damascus was chosen as capital for the new nation of Syria. Gouraud sensed this sentiment and tried to manipulate it by making Aleppo the capital of a large and wealthier state with which it would have been hard for Damascus to compete. The State of Aleppo as drawn by France contained most of the fertile area of Syria— namely it contained the fertile country of Aleppo in addition to the entire fertile basin of river Euphrates. The state also had access to sea via the autonomous Sanjak of Alexandretta. On the other hand, Damascus, which is basically an oasis on the fringes of the Syrian Desert, had neither enough fertile land nor access to sea. Basically, Gouraud wanted to lure Aleppo by giving it control over most of the agricultural and mineral wealth of Syria so that it would never want to unite with Damascus again.

However, the limited economic resources of the Syrian states made the option of completely independent states undesirable for France, because it threatened an opposite result— the states collapsing and being forced back into unity. This is why France proposed the idea of a Syrian federation that was realized in 1923. Initially, Gouraud envisioned the federation as encompassing all the states— even Lebanon. In the end however, only three states participated: Aleppo, Damascus, and the Alawite State. The capital of the federation was Aleppo at first, but it was relocated to Damascus. The president of the federation was Subhi Barakat, an Antioch-born politician from Aleppo.

The federation ended in December 1924, when France merged Aleppo and Damascus into a single Syrian State and separated the Alawite State again. This action came after the federation decided to merge the three federated states into one and to take steps encouraging Syria's financial independence— steps which France viewed as too much.

Post-independence

The period immediately following independence from France was marked by increasing rivalry between Aleppo and Damascus. Aleppo feverishly called for an immediate union between Syria and Hashimite Iraq, a demand that was firmly rejected by Damascus. Instead, Damascus favored a pro-Egyptian, pro-Saudi orientation and actively participated in the establishment of the Arab League in Alexandria in 1944, an organization that was seen by many Arab nationalists as a 'conspiracy' aimed against the unification of the Fertile Crescent under the Hashimites.

The increasing disagreements between Aleppo and Damascus led eventually to the split of the National Block into two factions: the National Party, established in Damascus in 1947, and the Popular Party, established in Aleppo in 1948 by Rushdi Kikhya and Nazim Qudsi. An underlying cause of the disagreement, in addition to the union with Iraq, was Aleppo's intention to relocate the capital from Damascus. The issue of the capital became an open debate matter in 1950 when the Popular Party presented a constitution draft that called Damascus a "temporary capital."

In December 1947, after the UN decided the partition of Palestine, an Arab mob attacked the Jewish quarter. Homes, schools and shops were badly damaged.[19] Many of the towns synagogues were attacked, including the ancient Great Synagogue which as completed gutted by fire. The damage was estimated at $2.5 million.[20] Soon after, many of the towns 6,000 Jews emigrated.[21]

The first coup d'état in modern Syrian history was carried out in March 1949 by an army officer from Aleppo, Hussni Zaim. However, lured by the absolute power he enjoyed as a dictator, Zaim soon developed a pro-Egyptian, pro-Western orientation and abandoned the cause of union with Iraq. This incited a second coup only four months after his. The second coup, led by Sami Hinnawi, empowered the Popular Party and actively sought to realize the union with Iraq. The news of an imminent union with Iraq incited a third coup the same year: in December 1949, Adib Shishakly led a coup preempting a union with Iraq that was about to be declared.

Soon after Shishakly's domination ended in 1954, a union with Egypt under Gamal Abdul Nasser was implemented in 1958. The union, however, collapsed only two years later when a junta of young Damascene officers carried out a separatist coup. Aleppo resisted the separatist coup, but eventually it had no choice but to recognize the new regime. The new regime tried to absorb Aleppo's dissent by appointing both a president and premier from Aleppo—Nazim Qudsi and Marouf Dawalibi.

In March 1963 a coalition of Baathists, Nasserists, and Socialists launched a new coup whose declared objective was to restore the union with Egypt. However, the new regime only restored the flag of the union. Soon thereafter disagreement between the Baathists and the Nasserists over the restoration of the union became a crisis, and the Baathists ousted the Nasserists from power. The Nasserists, most of whom were from the Aleppine middle class, responded with an insurgency in Aleppo in July 1963.

Again, the Baath regime tried to absorb the dissent of the Syrian middle class (whose center of political activity was Aleppo) by putting to the front Amin Hafiz, a Baathist military officer from Aleppo.

President Hafez Assad, who came to power in 1970, relied on support from the business class in Damascus. This gave Damascus further advantage over Aleppo, and hence Damascus came to dominate the Syrian economy. The strict centralization of the Syrian state, the intentional direction of resources towards Damascus, and the hegemony Damascus enjoys over the Syrian economy made it increasingly hard for Aleppo to compete. Hence, Aleppo is no longer an economic or cultural capital of Syria as it once used to be.

In 2006 Aleppo was named by the Islamic Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (ISESCO) as the capital of Islamic culture.[22]

Geography

The ancient city was built on a group of small hills such as Tell Sawda, Tell Aysha, Tell As-Sett, etc. Nowadays the city lies about 120 km (75 mi) inland from the Mediterranean Sea, on a plateau 380 meters above sea-level, 45 kilometers east of the Syrian-Turkish border checkpoint of Bab Al-Hawa. The old city of Aleppo, enclosed in its walls and gates, lies on the east of Quwēq river. The city is surrounded with fertile agricultural farms from the north and the west, widely cultivated with olive and pistachio trees. On the east Aleppo approaches the dry areas of the Syrian Badiyeh (Syrian desert).

Climate

| Climate data for Aleppo | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17 (63) |

21 (70) |

31 (88) |

34 (93) |

41 (106) |

47 (117) |

46 (115) |

43 (109) |

41 (106) |

37 (99) |

30 (86) |

18 (64) |

47 (117) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 10 (50) |

13 (55) |

18 (64) |

24 (75) |

29 (84) |

34 (93) |

36 (97) |

36 (97) |

33 (91) |

27 (81) |

19 (66) |

12 (54) |

24 (75) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1 (34) |

3 (37) |

4 (39) |

9 (48) |

13 (55) |

17 (63) |

21 (70) |

21 (70) |

15 (59) |

12 (54) |

7 (45) |

3 (37) |

11 (52) |

| Record low °C (°F) | -13 (9) |

-10 (14) |

-7 (19) |

-2 (28) |

0 (32) |

9 (48) |

16 (61) |

15 (59) |

7 (45) |

5 (41) |

-3 (27) |

-8 (18) |

-13 (9) |

| Precipitation mm (inches) | 89 (3.5) |

64 (2.52) |

38 (1.5) |

28 (1.1) |

8 (0.31) |

3 (0.12) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

25 (0.98) |

56 (2.2) |

84 (3.31) |

395 (15.55) |

| Source: BBC Weather[23] | |||||||||||||

Architecture

Aleppo is a city of several and mixed architectural styles. Numerous invaders, from Byzantines and Seljuks to Mamluks and Ottomans have left their architectural marks on the city, whose origins can be traced back more than 2000 years.[24]

There are various types of 13th and 14th centuries construction, such as caravanserais, Quranic schools and hammams, and the Christian and Islamic holy buildings of the old city and Jdeydeh quarter.

The Jdeydeh quarter is the home of many 16th and 17th century houses of the prestigious Aleppine bourgeoisie with magnificent stone engravings. Baroque architecture of the 19th and early 20th century is common in the Azizyeh quarter, e.g. the famous Villa Rose. The new chic Shahba quarter is a mixture of several styles, i.e. Neo-classic, Norman, Oriental and even Chinese architecture.[25]

Aleppo is entirely built of stone, particularly large white stones.

Culture

There is a relatively clear division between old and new Aleppo. The older portions were contained within a wall, 5 km in circuit with nine gates. The huge medieval castle in the city – known as the Citadel of Aleppo – occupies the center of the city.

Historical Aleppo

Historically, the old city of Aleppo was built around the acropolis where the citadel stands today. Aleppo flourished under many civilizations and developed a highly organized social, religious and economical structure early on in history. Being subjected to constant invasions and political instability, the inhabitants of the city were forced to build cell-like quarters and districts that were socially and economically independent. Each district was characterized by the religious and ethnic characteristics of its inhabitants. One of the finest examples of a cell-like quarter in Aleppo is Jdeydeh. After Timur Leng (also Tamburlaine and other spellings) invaded Aleppo in 1400 and destroyed it, the Christians migrated out of the city walls and established their own cell in the north western region of the city, thus founding the quarter of Jdeydeh. The inhabitants of Jdeydeh were mainly brokers who facilitated trade between foreign traders and local merchants.

Suqs and Khans

The city's strategic trading position attracted settlers of all races and beliefs who wished to take advantage of the commercial roads that met in Aleppo from as far as China and Mesopotamia to the east, Europe to the west, and the fertile crescent and Egypt to the south. The largest covered market, or suq, in the world is in in Aleppo, with an approximate area of 16 hectares and a length of 16 km (9.94 mi).

The Medina, as it is locally known, is an active trade centre for imported luxury goods, such as raw silk from Iran, spices and dyes from India, and coffee from Damascus. The Medina also is home to local products such as wool, agricultural products and soap. Most of the souqs date back to the 14th century and are named after various professions and crafts, hence the wool souq, the copper souq, and so on. Aside from trading, the souq accommodated the traders and their goods in khans (caravanserais) scattered in the souq. The khans also take their names after their location in the souq and function, and are characterized by their beautiful facades and entrances with fortified wooden doors.

The most important suqs of the old city include:[26]

- Khan Al-Qadi, built in 1450, is one of the oldest khans in Aleppo.

- Khan Al-Burghul (or bulgur), built in 1472, hosted the British general consulate of Aleppo until the beginning of the 20th century.

- Suq Al-Saboun or the soap khan, built in the beginning of the 16th century, located near the Aleppo soap markets.

- Khan Al-Shouneh, built in 1536. Currently functions as a market for trades and traditional handicrafts of the Aleppine art.

- Suq Khan Al-Nahhaseen or the coopery suq, built in 1539. It hosted the general consulate of Belgium during th 16th century. Nowadays, it is known for its traditional and modern shoe-trading shops with 84 stores.

- Suq Khan Al-Harir or the silk khan. Built in the second half of the 16th century, the khan has 43 stores mainly specialized in textile trading. It hosted the Iranian consulate until 1919.

- Suq Khan Al-Gumrok or the customs' khan, a textile trading centre with 55 stores. Built in 1574, Khan Al-Gumrok is considered to be the largest khan in ancient Aleppo.

- Suq Khan Al-Wazir, built in 1683, believed to be the main suq of cotton products in Aleppo.

- Suq Al-Attareen or the herbals' market. Traditionally, was the main spice-selling market of Aleppo. Currently, it is functioning as a textile-selling centre with 82 stores.

- Suq Al-Zirb (originally Suq Al-Dharb). Was the place where coins were struck during the Mamluk period. Nowadays, the suq has 71 shops, most of them sell textiles and the basic needs of the Bedouins.

- Suq Al-Behramiyeh located near the Behramiyeh mosque with 52 stores of food trade.

- Suq Al-Haddadeen is the old traditional balcksmiths' suq with its 37 workshopes.

- Suq Al-Atiq or the old suq, specialized in raw leather trading with 48 stores.

- Suq Al-Siyyagh or the jewelry market, is the main jewelry trade centre in Aleppo and Syria with 99 stores.

- The Venetians' Khan, was the home of the consul of Venice and the Venetian merchants.

- Suq Al-Niswan or the women's market, the place where all necessary accessories, clothes and wedding equipments of the bride could be found.

- Al-Suweiqa or Sweiqat Ali (Suweiqa means "small suq" in Arabic). This big suq contains a group of khans and markets largely specialized in home and kitchen eqipements.

Many traditional khans are also functioning as suqs in Jdeydeh quarter:

- Suq Al-Hokedun or "Khan al-Quds". Hokedun means "the spiritual house" in Armenian, as it was built to serve as a settlement for the Armenian pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem.[27] The old part of the Hokedun dates back to the late 15th and early 16th centuries while the newer parts were built during the 17th century. Nowadays, it is turned into a big suq within the old Christian quarter of Jdeydeh with a large number of stores specialized in garment trade.

- Suq Al-Souf or the wool market of Jdeydeh, surrounded with the ancient churches of the Christian quarter.

Historic buildings

- The Citadel, a large fortress built atop a huge, partially artificial mound rising 50 m above the city. The current structure dates from the 13th century and had been extensively damaged by earthquakes, notably in 1822.

- Madrasa Halawiye, built in 1124 on the original site of the Cathedral of St. Helen, where, according to tradition, a Roman temple had stood. Then Saint Helena, mother of Constantine the Great, built a great Byzantine cathedral there. When the Crusaders were pillaging the surrounding countryside, the city's chief judge converted St. Helena's cathedral into a mosque and finally, in the middle of the 12th century, Nur al-Din founded a madrasa or religious school here. Parts of the 6th century Christian construction, turned into an Islamic school after the Crusaders invasion, and including 6th century Byzantine columns, can be seen in the hall. It has also a fine 14th century mihrab.

- Madrasa Faradis ("School of the Paradise"), defined "the most beautiful of the mosques of Aleppo".[28] It was built by the widow of malek Zahir in 1234–1237, then regent for Nasir Yusuf. Notable is the courtyard, which has a pool in the middle surrounded by arches with ancient columns, sporting capitals with a honeycomb pattern. The same style characterizes the domes of the prayer hall. Also fine is the mirhab, decorated with arabesque motifs.

- Madrasa Moqaddamiye, the oldest theological school in the city (1168), with a porch sporting arabesque medallions. It was also converted to this use after the Crusades.

- Madrasa Zahiriye (1217).

- Madrasa Sultaniye, begun by malek Zahir and finished in 1223–1225 by his son al-Aziz. Noteworthy is the mirhab of the prayer room.

- Madrasa Al-Uthmaniyah (1730).

- Khanqah AL-Farafra, a 13th century sufi monastery (1237).

- Bimaristan Arghun al-Kamili, an asylum which worked from 1354 until the early 20th century.

- Beit Achiqbash, Beit Ghazaleh and Bait Dallal, 17th-18th centuries houses in the Jdeydeh quarter, showing fine decorations, nowadays turned into museums.

- National Library of Aleppo.

- Clock Tower of Bab Al Faraj.

- Grand Seray d'Alep, the former seat of the governor of Aleppo.

Religious buildings

- Great Mosque of Aleppo (Jāmi‘ Bani Omayya al-Kabīr), founded c. 715 by Umayyad caliph Walid I and most likely completed by his successor Suleyman. The building contains a tomb associated with Zachary, father of John the Baptist. Construction of the present structure for Nur al-Din commenced in 1158. However, it was damaged during the Mongol invasion of 1260, and was rebuilt. The 45 m-high tower (described as "the principal monument of medieval Syria")[28] was erected in 1090–1092 under the first Seljuk sultan, Tutush I. It has four façades with different styles.

- Al-Nuqtah Mosque ("Mosque of the drop [of blood]"), a Shī‘ah mosque, which contains a stone said to be marked by a drop of Husayn's blood. The site is believed to have previously been a monastery, which was converted into a mosque in 944.

- Al-Tuteh mosque of the Ayyubid-era, which includes the ancient Roman triumpal arch, which once marked the beginning of the decumanus. It has 12th century kufic inscription and decorations.

- Altun Bogha mosque built in 1318.

- Al-Sahibiyah mosque built in 1350, adjacent to Khan Al-Wazir.

- Al-Tavashi mosque built during the 14th century and restored in 1537. Has a great façade decorated with colonnettes.

- The small funerary Al-Otrush mosque, built in 1403, in Mameluke style. It has a highly decorated entrance portal in the fine façade.

- Al-Saffahiyah mosque, erected in 1425, with a preciously decorated octagonal minaret.

- Khusruwiyah Mosque completed in 1547, designed by the famous Armenian-Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan.

- Al-Adeliye mosque, built in 1555 the governor of Aleppo Muhammed Pasha. It has a prayer hall preceded by an arcade, with a dome, a mihrab with local faience tiles.

- Al-Qaiqan mosque ("Mosque of the Crows"), with two ancient columns in basalt near the entrance. It includes a stone block with a Hittite inscription.

- Al-Shibani Church is an old Sunday school and church of the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary located in the old city, currently used as a cultural centre.

- The Forty Martyrs Armenian cathedral of the 15th century located in Jdeydeh quarter.

- Mar Assia Al-Hakim Syriac Catholic church of the 15th century in Jdeydeh.

- The Dormition of Our Lady Greek Orthodox church of the 15th century in Jdeydeh.

- Many other churches in Jdeydeh Christian quarter such as the Maronite Saint Elias Cathedral, the Armenian Catholic Cathedral of Our Mother of Reliefs and the Melkite Greek Catholic Cathedral of Virgin Mary.

- The Central Synagogue of Aleppo or Al-Bandara synagogue, built circa 1200 by the Jewish community; renovated recently by the efforts of Aleppine Jewish migrants in USA.

Gates

The old part of the city was surrounded with thick walls pierced by the nine historical gates (of which five are preserved) of ancient Aleppo:

- Bab al-Hadid (باب الحديد) (Iron Gate).

- Bab al-Maqam (باب المقام) (Gate of the Shrine).

- Bab Antakeya (باب انطاكية) (Gate of Antioch).

- Bab al-Nasr (باب النصر) (Victory Gate).

- Bab al-Faraj (باب الفرج) (Gate of Deliverance).

- Bab Qinnasrin (باب قنسرين) (Gate of Qinnasrin).

- Bāb Jnēn (باب الجنان) (Gate of Gardens).

- Bab al-Ahmar (باب الأحمر) (Red Gate).

- Bab al-Nairab (باب النيرب) (Gate of Nairab).

Arts

Aleppo is considered one of the main centres of Arabic traditional and classic music with the famous Aleppine Muwashshahs, Qudoods and Maqams (religious and secular poetic-musical genres). Aleppines in general are fond of Arab classical music, the Tarab, and it is not a surprise that many artists from Aleppo are considered pioneers among the Arabs in classic and traditional music. The most prominent figures in this field are Sabri Mdallal, Sabah Fakhri, Shadi Jameel, Abed Azrie and Nour Mhanna. Aleppo hosts many music festivals every year, the most popular one is the Syrian Song Festival which is being organized every two years in the citadel amphitheatre. Many iconic artists of the Arab music like Sayed Darwish and Mohammed Abdel Wahab were visiting Aleppo to recognize the legacy of Aleppine art and learn from its cultural heritage.

Preservation of the ancient city

As an ancient trading centre, Aleppo's impressive suqs, khans, hammams, madrasas, mosques and churches are all in need of more care and preservation work. After World War II, the city was significantly redesigned; in 1952 French architect André Gutton had a number of wide new roads cut through the city to allow easier passage for modern traffic. In the 1970s large parts of the older city were demolished to allow for the construction of modern apartment blocks. As awareness for the need to preserve this unique cultural heritage increased, Gutton's master plan was finally abandoned in 1979 paving the way for UNESCO to declare the Old City of Aleppo a World Heritage Site in 1986. Several international institutions have joined efforts with local authorities to rehabilitate the old city of Aleppo by accommodating contemporary life while preserving the old one. The governorate and the municipality are implementing serious programmes directed towards the enhancement of the old city and Jdeydeh quarter.

Demographics

70% of Aleppo's inhabitants are Sunni Muslims. They are mainly Arab, but other ethnicities include Turkmens, Adyghe, Albanians, Bosnians, Bulgarians, Chechens, Circassians, Kabardin and Kurds.

Aleppo has one of the largest Christian communities in the Middle East, mainly Armenians and Syrian Christians. The majority of the Syrian Christians in Aleppo speak the Armenian language and hail from the city of Urfa in Turkey. Aleppo’s large Christian population swelled with the influx of Armenian and Syrian Christian refugees during the early 20th-century and after the Armenian Genocide of 1915, Armenians formed a quarter of the city's population.[29] Between 15% and 20% of the population of Aleppo are members of Christian Orthodox congregations, including the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Syrian Orthodox Church and the Greek Orthodox Church. There is also a strong presence of Catholic Christians in the city including Maronites, Latins, Melkite Greeks and Syrian Catholics. Evangelical Christians are a minority in the city.

Several areas have a Christian and Armenian majority, such as the old Christian quarter of Jdeydeh. Modern Christian districts include Aziziyeh, Sleimaniyeh and Meydan. There are 45 operating churches in the city, possessed by the abovementioned Christian congregations.

The city was home to a Jewish population from ancient times. The Great Synagogue, built in the 5th century, housed the Aleppo codex. In the early 20th-century, the towns Jews mainly lived in Al-Jamiliyah, Bab Al-Naser and the neighborhoods around the Great Synagogue. Unrest in Palestine in the years preceding the establishment of Israel in 1948 resulted in growing hostility towards Jews living in Arab countries. Following the 1947 pogrom, most of the 10,000 strong community emmigated.[30] In 1968, there were an estimated 700 Jews still remaining in Aleppo.[31]

Up to day, the properties and houses of the Jewish families which were not sold after the migration, remain uninhabited under the protection of Syrian Government. Most of these properties are in Al-Jamiliyah and Bab Al-Naser areas, and the neighborhoods around the Central synagogue of Aleppo. Eventually, the Syrian government lifted restriction on its Jewish citizens with the sole condition that they did not travel to Israel to settle there. Most travelled to the USA, where a sizeable Syrian Jewish community currently exists in Brooklyn, New York. Today, only a handful of Jewish families live in Aleppo, and many of the buildings such as the synagogue and the Jewish school remain empty, only to be used for special events and religious ceremonies.

| Historical populations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | %± |

| 1932 | 232,000 | — |

| 1946 | 319,867 | 37.9% |

| 1986 | 1,200,000 | 275.2% |

| 2004 | 2,181,061 | 81.8% |

The Maronite Saint Elias Cathedral |

Armenian Apostolic church of the Holy Mother of God |

Ar-Rahman mosque |

Tourism and amusement

Being one of the oldest cities in the world and a major centre on the ancient Silk Road, Aleppo has a number of impressive and attractive structures, in addition to the natural beauty of the region. The most splendid landmarks of the city around the citadel are the suqs, the old baths (hammams), the khans with numerous religious and cultural centres. On the other hand, the city has a large number of different modern facilities which attract tourists from all over the world, such as many luxurious hotels, casinos, bars and restaurants with their famous Aleppine foods and kebabs (grills). Many old Arabic and Armenian houses in the old city and Jdeydeh quarter are redesigned nowadays, to be used as oriental hotels, piano bars, pubs and restaurants.

- Famous hammams of Aleppo include: Hammam Yalbugha, Hammam Al-Nahhaseen and Hammam Bab Al-Ahmar.

- The Public Park of Aleppo which was opened in the 1940s is the largest in Syria. It is located in Aziziyeh area, where Quwēq river breaks through the green park.

- Museums: The National Museum of Aleppo is a journey throughout the history of Syrian civilizations, while the Aleppine House or Beit Achiqbash (built in 1757) in Jdeydeh is the museum of popular traditions of Aleppo. The old Armenian church of the Holy Mother of God is currently turned into the Zarehian Museum of the Armenian Apostolic Church, also located in Jdeydeh quarter.

- The Blue Lagoon: A modern water park located just outside Aleppo. It has several pools, toboggans, bars and restaurants.

- There are many cinema halls in the city; most of them are located on the Baron street, among them is the famous Cine d'Alep.

- Club d'Alep with its summer and winter branches: The private club with more than 600 local members has a unique tradition, being the only one of its type in the Syrian Arab Republic. The club is known for bridge games and other trick-taking card games.

A new wave of visitors is rediscovering this ancient trading centre, as tensions between Damascus and Washington begin to ease, as well as due to the recent loosening of visa restrictions with Turkey.

Nearby attractions

.jpg)

Aleppo is surrounded with plenty of historical sites, the Dead Cities, which are a group of 700 abandoned settlements in northwest Syria around the city of Aleppo. Those cities date back to before the fifth century B.C and contain many remains of Christian Byzantine architecture.

Important dead cities include:

- Church of Saint Simeon Stylites (Deir Semaan), a well preserved church dates back to the 5th century, located about 30 km (19 mi) north-west of Aleppo.

- Ebla, ruins of one of the oldest known Semitic cities, about 55 km (34 mi) south-west of Aleppo.

- Brad, an ancient settlement, 35 km (22 mi) west of Aleppo; the site of Saint Julianus Maronite monastery (built between 399-402 A.D) where the shrine of Saint Maron is located.

- Ain Dara temple, an Iron Age Syro-Hittite temple, located 55 km (34 mi) north-west of Aleppo.

- Cyrus, an ancient city 70 km (43 mi) north-west of Aleppo; the site of "Nabi Houri church", an old Roman amphitheatre and two old Roman bridges on Afrin river.

- Kimar settlement near Basuta village, 33 km (21 mi) north-west of Aleppo. A historical village of the Roman and the Byzantine eras, backs to the fifth century A.D, contains many well-preserved churches, towers and old water reservoirs.

- Mushabbak Church, an ancient Roman basilic of the late 5th century A.D, located around 20 km (12 mi) west of Aleppo. The temple is one of the best preserved churches in the "Dead Cities".

- Qalb Lozeh Church ("Heart of the Almond"), is one of the most celebrated ecclesiastical monuments in Syria dating back to the second half of 5th century, located 65 km (40 mi) west of Aleppo.

- Bab Al-Hawa village, 45 km (28 mi) west of Aleppo on the Turkish border; the site of many old churches of the fourth century A.D and a well preserved historical gate from the sixth century A.D.

Many other sites and dead cities in the area, are located on various distances around Aleppo such as Serjilla, Bara, Qal'at Najm, Deir Meshmesh, Deir Amman, Tell A'ade Church, etc.

The western regions around Aleppo are characterized with beautiful natural landscapes, scenic views and a mild weather, which made the area a popular and touristic destination, such as Basuta village, Kafar Janneh village and Midanki lake.

Economy

Trade and industry

The main role of the city was as a trading place throughout the history, as it sat at the crossroads of two trade routes and mediated the trade from India, the Tigris and Euphrates regions and the route coming from Damascus in the South, which traced the base of the mountains rather than the rugged seacoast. Although trade was often directed away from the city for political reasons, it continued to thrive until the Europeans began to use the Cape route to India and later to utilize the route through Egypt to the Red Sea.

The commercial traditions in Aleppo have deep roots in the history. The commercial chamber of Aleppo which was founded in 1885, is one of the oldest chambers in the Middle East and the Arab world. According to many historians, Aleppo was the most developed commercial and industrial city in the Ottoman Empire after Constantinople and Cairo.

Nowadays Aleppo has the most developed commercial and industrial plants in Syria, therefore, it is considered the commercial and industrial centre of the republic. The most developed industrial sectors in the city are: textiles, electricals, chemicals, software, agricultural and food industries. Aleppo is also famous for manufacturing precious metals and stones.

The industrial city of Aleppo in Sheikh Najjar district is one of the largest ones in Syria and the region. It covers an area of 4412 hectares in the north-east of Aleppo, with an investment of 2 billion US dollars as of the end of 2009. The industrial area is still under development. It is envisaged to open hotels, exhibition centres and other structures within the industrial city.

The old traditional crafts are well-preserved in the old part of the city. The laurel soap of Aleppo with its worldwide fame, is considered to be the world's first hard soap.[32]

Construction

Aleppo is one of the fastest-growing cities in Syria and the Middle East. Many villagers and inhabitants of other Syrian districts are migrating to Aleppo in an effort to find better job opportunities, a fact that always increases population pressure, with a growing demand for new residential capacity. New districts and residential communities have been built in the suburbs of Aleppo, many of them still under construction as of 2010[update].

Two major construction projects are scheduled in Aleppo: the "Old City Revival" project and the "Reopening of the stream bed of Quwēq River". The Old City revival project completed its first phase by the end of 2008, and the second phase started in early 2010. The purpose of the project is the preservation of the old city of Aleppo with its souqs and khans, and restoration of the narrow alleys of the old city and the roads around the citadel. The second project is directed towards the revival of the flow of the Quwēq River, demolishing both the artificial cover of the stream bed and the reinforcement of the stream banks along the river in the city centre. The flow of the river was blocked during the 1960s by the Turks, turning the river into a tiny sewage channel, leading the authorities to cover the stream. In 2006 the flow of pure water was restored through the efforts of the Syrian government, thus granting a new life to the Quwēq River.

Transport

Railway

Aleppo was one of the first parts of Syria to obtain railway connection, with the Ottoman Empire building the Baghdad Railway through the city in 1912. The connections to Turkey and onwards to Ankara still exist today, with a twice weekly train from Damascus. It is perhaps for this historical reason that Aleppo is the headquarters of Syria national railway network, Chemins de Fer Syriens. As the railway has a relatively slow speed of passage, much of the passenger traffic to the port of Latakia had moved to road based air-conditioned coaches. But this has reversed in recent years with the 2005 introduction of South Korean built DMU's proving regular bi-hourly express service to both Latakia and Damascus, which miss intermediate stations.

Airport

Aleppo International Airport (IATA: ALP, ICAO: OSAP) is the international airport serving the city. The airport serves as a secondary hub for Syrian Arab Airlines.

_cropped.jpg)

Education

As the main economical centre of Syria, Aleppo has a large number of educational institutions. Along with the Aleppo University, there are state colleges and private universities which attract large numbers of students from other regions of Syria and the Arab countries. The number of the students in Aleppo University is more than 60 thousand. The university has 18 faculties and 8 technical colleges in the city of Aleppo.

As of 2010, there are three private universities operating in the city: Private University of Science & Arts (PUSA), Gulf University (GU), and Mamoun University for Science & Technology (MUST).

Branches of the state conservatory and the fine arts school are also operating in the city.

Aleppo is home to several private Christian & Armenian schools, and two international schools: International School of Aleppo and Lycée Français d'Alep.

Sports

The most favourite and popular sport in Aleppo is football. Aleppo has many football clubs, among which only Al-Ittihad of Aleppo, plays in the Syrian National Football League's top division for the season 2009–2010.

Here is a list of the five major sport clubs in the city of Aleppo:

| Club |

|---|

| Ettihad of Aleppo |

| Al-Horriya |

| Jalaa Club |

| Al-Yarmouk Sports Club |

| Ourubeh Club |

Al-Ittihad is the biggest and most popular club in Syria. Al-Ittihad has its own stadium with a capacity of 12,000 spectators. But because of the huge number of their supporters, they use the city's main stadiums, Al-Hamadaniah Stadium and the Aleppo International Stadium. While 2nd division teams like Al-Horriya and Al Yarmouk, use the April 7th Municipal Stadium which can serve around 17,000 spectators.

Basketball is also very popular in Aleppo. Four clubs out of 12 in Syrian Basketball top division are from Aleppo. On the other hand, five clubs from Aleppo are included in the women's top division. The clubs of Aleppo are totally dominating the basketball leagues in Syria, especially Jalaa and Al-Ittihad. Al-Yarmouk and Al-Horriya are also included in the top division, both in men's and women's competitions, while Ourubeh club plays in the women's top division and the in men's second division.

Too many types of sports are also being practiced by the mentioned clubs and other small clubs. Tennis, Handball, Volleyball, Table Tennis and Swimming are among the favorites.

Cuisine

The Syrian cuisine in general and especially the Aleppine cuisine is very rich of its multiple types of dishes. Being surrounded by olive, nut and fruit orchards, Aleppo is famous for a love of eating, as the cuisine is the product of fertile land and location along the Silk Road. Therefore, it's not a surprise that the International Academy of Gastronomy in France awarded Aleppo its culinary prize in 2007.[33] But in fact, Aleppo was a food capital long before Paris, because of its diverse communities combined by Arabs, Kurds, Armenians, Circassians and a sizable Arab Christian population. All of those groups contributed food traditions, since Aleppo was part of the Ottoman Empire.

The city has a vast selection of different types of dishes, such as kabab, kibbeh, dolma, hummus, ful halabi, za'atar halabi, etc. Ful halabi, is a typical Aleppine breakfast meal: fava bean soup with a splash of olive oil, lemon juice and Aleppo's red peppers. The kibbeh is one of the most favourite foods for the locals, and that's why the Aleppines have invented more than 17 types of kibbeh dishes, which is considered a form of art for them. The most favourite drink is Arak, which is usually consumed along with meze and Aleppine grills and kibbehs. The za'atar of Aleppo (Thyme) is a type of Syrian oregano which is very favourite among Arabs, Armenians and Turks.

Aleppo is the origin of many different types of sweets and pastries. The Aleppine sweets are characterized to contain high rates of ghee butter and sugar, such as mabrumeh, swar es-sett, balloriyyeh, etc. Other sweets include mamuniyeh, shuaibiyyat, mushabbak, zilebiyeh, ghazel al-banat etc. Most of the pastries can contain the renowned Aleppine pistachios or other types of nuts.

Program for Sustainable Urban Development in Syria

The “Program for Sustainable Urban Development in Syria” (UDP) is a joint undertaking of the German Technical Cooperation GTZ, the Syrian Ministry for Local Administration and Environment (MLAE), and several other Syrian partner institutions. The program promotes capacities for sustainable urban management and development at the national and municipal level. Four components have been agreed as major fields of cooperation during the first phase (2007–2009):

- Urban development in the city of Aleppo; this includes further support to the rehabilitation of the Old City, as well as to a long-term oriented city development strategy (CDS) and the management of informal settlements.

- Rehabilitation of the Old City of Damascus; this will build on instruments and experiences established during the urban rehabilitation support for Old Aleppo.

- Promoting support structures for municipalities; this includes capacity building, networking, and promoting municipal strength in the national development dialogue.

- Policy advice on urban development; rapid urbanization in Syria requires adequate legislative and institutional frame-conditions as well as specific promotional programs for urban development.

The UDP cooperates closely with other interventions in the sector, namely the EU-supported 'Municipal Administration Modernization' program. It is planned to operate from 2007 to 2016.

International relations

Twin towns—Sister cities

Izmir, Turkey since 5 May 1993.[34]

Izmir, Turkey since 5 May 1993.[34] Lyon, France since 18 October 2000.[35]

Lyon, France since 18 October 2000.[35] Gaziantep, Turkey since 13 November 2005.[36]

Gaziantep, Turkey since 13 November 2005.[36] Brest, Belarus since 28 January 2010.[37]

Brest, Belarus since 28 January 2010.[37]

Notable people

|

|

Photo gallery

|

Panoramic view from the citadel |

Al-Sahibiyah mosque built (1350) |

Al-Saffahiyah mosque (1425) |

Hammam Yalbugha (1491) |

In the old Christian quarter of Jdeydeh |

The National Museum of Aleppo |

Musicians from Aleppo, 1915 |

Aleppo Citadel in 1921 |

The police station of Aziziyeh area in 1921 |

The city centre with Quwēq River in the 1920s |

Trams crossing the old streets of Aleppo in the 1920s |

| Preceded by Mecca |

Capital of islamic culture 2006 |

Succeeded by Fes |

See also

- Language of Aleppo

- Al-Shibani Building

- List of churches in Aleppo

- Aleppo Codex

- Central Synagogue of Aleppo

References

- Notes

- ↑ Syria News statement by Syrian Minister of Local Administration, Syria (Arabic, August 2009)

- ↑ Central Bureau of Statistics Syria Syria census 2004

- ↑ "UN Demographic Yearbook 2009". http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/dyb/dyb2007/notestab08.pdf. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ "Central Bureau of Statistics, Estimates of Population actually living in Syria on 1/1/2009". http://www.cbssyr.org/middle.files/pag1.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- ↑ Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archeology. "Pre- and Protohistory in the Near East: Tell Qaramel (Syria)". http://www.pcma.uw.edu.pl/cas/index.php?p=111. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ↑ Alexander Russell, ed (1856). The Natural History of Aleppo (1st ed.). London: Unknown. p. 266.

- ↑ Travels of Rabbi Pesachia of Regensburg. teachittome.com (p. 53).

- ↑ Pettinato, Giovanni (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991) Ebla, a new look at history p.135

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Hawkins, John David (2000) Inscriptions of the iron age p.388

- ↑ Kuhrt, Amélie (1998) The ancient Near East p.100

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Phenix, Robert R. (2008) The sermons on Joseph of Balai of Qenneshrin

- ↑ Jackson, Peter (July 1980). "The Crisis in the Holy Land in 1260". The English Historical Review 95 (376): 481–513.

- ↑ "Histoire des Croisades", René Grousset, p. 581, ISBN 226202569X.

- ↑ Runciman, p. 314.

- ↑ Runciman, pp. 336–337.

- ↑ Runciman, p. 463.

- ↑ Battle of Aleppo@Everything2.com.

- ↑ Gaskin, James J. 1846 Geography and sacred history of Syria p.33

- ↑ James A. Paul. Human rights in Syria, Middle East Watch. pg. 91.

- ↑ Willem Adriaan Veenh. Case studies on human rights and fundamental freedoms: a world survey, Volume 1, BRILL, 1975. pg. 90. ISBN 9024717795.

- ↑ American Jewish year book, Volume 50 and American Jewish year book, Volume 50, American Jewish Committee, 1949. pg. 441.

- ↑ حلب عاصمة الثقافة الإسلامية-Aleppo the Capital of Islamic Culture. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ↑ "Average Conditions Aleppo, Syria". BBC Weather. http://www.bbc.co.uk/weather/world/city_guides/results.shtml?tt=TT002840. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ↑ Reuters:Travel Postcard: 48 hours in Aleppo, Syria

- ↑ Middleeast.com:Aleppo

- ↑ "Aleppo.us: Old suqs of Aleppo (in Arabic)". http://www.aleppo.us/news/47.html.

- ↑ "Aleppo.us: Khans of Aleppo (in Arabic)". http://www.aleppo.us/news/22.html.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Burns, Russ (1999). Monuments of Syria. New York, London. p. 35.

- ↑ Hovannisian, Richard G. (2004). The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 425. ISBN 1-4039-6422-X.

- ↑ Walter P. Zener, "A Global community - the jews from aleppo, syria", pp. 35, 82.

- ↑ Avi Beker. Jewish Communities of the World, Lerner Publishing Group, 1998. pg. 208. ISBN 0822598221.

- ↑ Aleppo Soap Soap History

- ↑ "NPR web: Food Lovers Discover The Joys Of Aleppo". http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=122058669.

- ↑ (in Turkish) "Izmir sister cities". http://www.izmir-yerelgundem21.org.tr/kardes.htm (in Turkish).

- ↑ "Partner Cities of Lyon and Greater Lyon". © 2008 Mairie de Lyon. http://www.lyon.fr/vdl/sections/en/villes_partenaires/villes_partenaires_2/?aIndex=1. Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- ↑ (in Turkish) "Gaziantep cultural committee: Gaziantep sister cities, Aleppo-Syria". http://www.gaziantepkultursanat.org/gaziantep/kardes_sehirleri/halep.htm (in Turkish).

- ↑ (in Arabic) "Jamahir newspaper: 28 January 2010". http://jamahir.alwehda.gov.sy/_View_news2.asp?FileName=103164560320100127234904 (in Arabic).

External links

- Ernst Herzfeld Papers, Series 5: Drawings and Maps, Records of Aleppo Collections Search Center, S.I.R.I.S., Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

- Official site of Aleppo city

- Organization of World Heritage Cities

- Aleppo news and services (eAleppo)

|

|||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||