Textile

A textile is a flexible material consisting of a network of natural or artificial fibres often referred to as thread or yarn. Yarn is produced by spinning raw wool fibres, linen, cotton, or other material on a spinning wheel to produce long strands.[1] Textiles are formed by weaving, knitting, crocheting, knotting, or pressing fibres together (felt).

The words fabric and cloth are used in textile assembly trades (such as tailoring and dressmaking) as synonyms for textile. However, there are subtle differences in these terms in specialized usage. Textile refers to any material made of interlacing fibres. Fabric refers to any material made through weaving, knitting, spreading, crocheting, or bonding. Cloth refers to a finished piece of fabric that can be used for a purpose such as covering a bed.

Contents |

History

The discovery of dyed flax fibres in a cave in the Republic of Georgia dated to 34,000 BCE suggests textile-like materials were made even in prehistoric times.[2][3]

The production of textiles is a craft whose speed and scale of production has been altered almost beyond recognition by industrialization and the introduction of modern manufacturing techniques. However, for the main types of textiles, plain weave, twill or satin weave, there is little difference between the ancient and modern methods.

Incas have been crafting quipus (or khipus) made of fibres either from a protein, such as spun and plied thread like wool or hair from camelids such as alpacas, llamas and camels or from a cellulose like cotton for thousands of years. Khipus are a series of knots along pieces of string. They have been believed to only have acted as a form of accounting, although new evidence conducted by Harvard professor, Gary Urton, indicates there may be more to the khipu than just numbers. Preservation of khipus found in museum and archive collections follow general textile preservation principles and practice.

Uses

Textiles have an assortment of uses, the most common of which are for clothing and containers such as bags and baskets. In the household, they are used in carpeting, upholstered furnishings, window shades, towels, covering for tables, beds, and other flat surfaces, and in art. In the workplace, they are used in industrial and scientific processes such as filtering. Miscellaneous uses include flags, backpacks, tents, nets, cleaning devices such as handkerchiefs and rags, transportation devices such as balloons, kites, sails, and parachutes, in addition to strengthening in composite materials such as fibreglass and industrial geotextiles. Children can learn using textiles to make collages, sew, quilt, and make toys.

Textiles used for industrial purposes, and chosen for characteristics other than their appearance, are commonly referred to as technical textiles. Technical textiles include textile structures for automotive applications, medical textiles (e.g. implants), geotextiles (reinforcement of embankments), agrotextiles (textiles for crop protection), protective clothing (e.g. against heat and radiation for fire fighter clothing, against molten metals for welders, stab protection, and bullet proof vests). In all these applications stringent performance requirements must be met. Woven of threads coated with zinc oxide nanowires, laboratory fabric has been shown capable of "self-powering nanosystems" using vibrations created by everyday actions like wind or body movements.[4][5]

Fashion and textile designers

Fashion designers commonly rely on textile designs to set their fashion collections apart from others. Armani, Marisol Deluna, Nicole Miller, Lilly Pulitzer, the late Gianni Versace and Emilio Pucci can be easily recognized by their signature print driven designs.

Sources and types

Textiles can be made from many materials. These materials come from four main sources: animal (wool, silk), plant (cotton, flax, jute), mineral (asbestos, glass fiber), and synthetic (nylon, polyester, acrylic). In the past, all textiles were made from natural fibres, including plant, animal, and mineral sources. In the 20th century, these were supplemented by artificial fibres made from petroleum.

Textiles are made in various strengths and degrees of durability, from the finest gossamer to the sturdiest canvas. The relative thickness of fibres in cloth is measured in deniers. Microfibre refers to fibres made of strands thinner than one denier.

Animal textiles

Animal textiles are commonly made from hair or fur.

Wool refers to the hair of the domestic goat or sheep, which is distinguished from other types of animal hair in that the individual strands are coated with scales and tightly crimped, and the wool as a whole is coated with a wax mixture known as lanolin (aka wool grease), which is waterproof and dirtproof . Woollen refers to a bulkier yarn produced from carded, non-parallel fibre, while worsted refers to a finer yarn which is spun from longer fibres which have been combed to be parallel. Wool is commonly used for warm clothing. Cashmere, the hair of the Indian cashmere goat, and mohair, the hair of the North African angora goat, are types of wool known for their softness.

Other animal textiles which are made from hair or fur are alpaca wool, vicuña wool, llama wool, and camel hair, generally used in the production of coats, jackets, ponchos, blankets, and other warm coverings. Angora refers to the long, thick, soft hair of the angora rabbit.

Wadmal is a coarse cloth made of wool, produced in Scandinavia, mostly 1000~1500CE.

Silk is an animal textile made from the fibres of the cocoon of the Chinese silkworm. This is spun into a smooth, shiny fabric prized for its sleek texture.

Plant textiles

Grass, rush, hemp, and sisal are all used in making rope. In the first two, the entire plant is used for this purpose, while in the last two, only fibres from the plant are utilized. Coir (coconut fibre) is used in making twine, and also in floormats, doormats, brushes, mattresses, floor tiles, and sacking.

Straw and bamboo are both used to make hats. Straw, a dried form of grass, is also used for stuffing, as is kapok.

Fibres from pulpwood trees, cotton, rice, hemp, and nettle are used in making paper.

Cotton, flax, jute, hemp, modal and even bamboo fibre are all used in clothing. Piña (pineapple fibre) and ramie are also fibres used in clothing, generally with a blend of other fibres such as cotton. Nettles have also been used to make a fibre and fabric very similar to hemp or flax. The use of milkweed stalk fibre has also been reported, but it tends to be somewhat weaker than other fibres like hemp or flax.

Acetate is used to increase the shininess of certain fabrics such as silks, velvets, and taffetas.

Seaweed is used in the production of textiles. A water-soluble fibre known as alginate is produced and is used as a holding fibre; when the cloth is finished, the alginate is dissolved, leaving an open area

Lyocell is a man-made fabric derived from wood pulp. It is often described as a man-made silk equivalent and is a tough fabric which is often blended with other fabrics - cotton for example.

Fibres from the stalks of plants, such as hemp, flax, and nettles, are also known as 'bast' fibres.

Mineral textiles

Asbestos and basalt fibre are used for vinyl tiles, sheeting, and adhesives, "transite" panels and siding, acoustical ceilings, stage curtains, and fire blankets.

Glass Fibre is used in the production of spacesuits, ironing board and mattress covers, ropes and cables, reinforcement fibre for composite materials, insect netting, flame-retardant and protective fabric, soundproof, fireproof, and insulating fibres.

Metal fibre, metal foil, and metal wire have a variety of uses, including the production of cloth-of-gold and jewelry. Hardware cloth is a coarse weave of steel wire, used in construction.

Synthetic textiles

All synthetic textiles are used primarily in the production of clothing.

Polyester fibre is used in all types of clothing, either alone or blended with fibres such as cotton.

Aramid fibre (e.g. Twaron) is used for flame-retardant clothing, cut-protection, and armor.

Acrylic is a fibre used to imitate wools, including cashmere, and is often used in replacement of them.

Nylon is a fibre used to imitate silk; it is used in the production of pantyhose. Thicker nylon fibres are used in rope and outdoor clothing.

Spandex (trade name Lycra) is a polyurethane product that can be made tight-fitting without impeding movement. It is used to make activewear, bras, and swimsuits.

Olefin fibre is a fibre used in activewear, linings, and warm clothing. Olefins are hydrophobic, allowing them to dry quickly. A sintered felt of olefin fibres is sold under the trade name Tyvek.

Ingeo is a polylactide fibre blended with other fibres such as cotton and used in clothing. It is more hydrophilic than most other synthetics, allowing it to wick away perspiration.

Lurex is a metallic fibre used in clothing embellishment.

Milk proteins can also be used to create synthetic fabric. Milk or casein fibre cloth was developed during World War I in Germany, and further developed in Italy and America during the 1930s.[6] Milk fibre fabric is not very durable and wrinkles easily, but has a pH similar to human skin and possesses anti-bacterial properties. It is marketed as a biodegradable, renewable synthetic fibre.[7]

Production methods

Weaving is a textile production method which involves interlacing a set of longer threads (called the warp) with a set of crossing threads (called the weft). This is done on a frame or machine known as a loom, of which there are a number of types. Some weaving is still done by hand, but the vast majority is mechanised.

Knitting and crocheting involve interlacing loops of yarn, which are formed either on a knitting needle or on a crochet hook, together in a line. The two processes are different in that knitting has several active loops at one time, on the knitting needle waiting to interlock with another loop, while crocheting never has more than one active loop on the needle.

Spread Tow is a production method where the yarn are spread into thin tapes, and then the tapes are woven as warp and weft. This method is mostly used for composite materials, Spread Tow Fabrics can be made in carbon, aramide, etc.

Braiding or plaiting involves twisting threads together into cloth. Knotting involves tying threads together and is used in making macrame.

Lace is made by interlocking threads together independently, using a backing and any of the methods described above, to create a fine fabric with open holes in the work. Lace can be made by either hand or machine.

Carpets, rugs, velvet, velour, and velveteen, are made by interlacing a secondary yarn through woven cloth, creating a tufted layer known as a nap or pile.

Felting involves pressing a mat of fibres together, and working them together until they become tangled. A liquid, such as soapy water, is usually added to lubricate the fibres, and to open up the microscopic scales on strands of wool.

Nonwoven textiles are manufactured by the bonding of fibres to make fabric. Bonding may be thermal, mechnical or adhessives can be used.

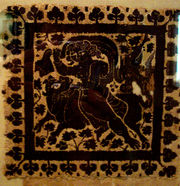

Treatments

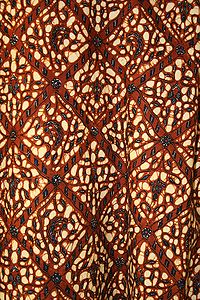

Textiles are often dyed, with fabrics available in almost every colour. The dying process often requires several dozen gallons of water for each pound of clothing.[9] Coloured designs in textiles can be created by weaving together fibres of different colours (tartan or Uzbek Ikat), adding coloured stitches to finished fabric (embroidery), creating patterns by resist dyeing methods, tying off areas of cloth and dyeing the rest (tie-dyeing), or drawing wax designs on cloth and dyeing in between them (batik), or using various printing processes on finished fabric. Woodblock printing, still used in India and elsewhere today, is the oldest of these dating back to at least 220CE in China. Textiles are also sometimes bleached, making the textile pale or white.

Textiles are sometimes finished by chemical processes to change their characteristics. In the 19th century and early 20th century starching was commonly used to make clothing more resistant to stains and wrinkles. Since the 1990s, with advances in technologies such as permanent press process, finishing agents have been used to strengthen fabrics and make them wrinkle free.[1] More recently, nanomaterials research has led to additional advancements, with companies such as Nano-Tex and NanoHorizons developing permanent treatments based on metallic nanoparticles for making textiles more resistant to things such as water, stains, wrinkles, and pathogens such as bacteria and fungi.[10]

More so today than ever before, textiles receive a range of treatments before they reach the end-user. From formaldehyde finishes (to improve crease-resistance) to biocidic finishes and from flame retardants to dyeing of many types of fabric, the possibilities are almost endless. However, many of these finishes may also have detrimental effects on the end user. A number of disperse, acid and reactive dyes (for example) have been shown to be allergenic to sensitive individuals.[11] Further to this, specific dyes within this group have also been shown to induce purpuric contact dermatitis.[12] Although formaldehyde levels in clothing are unlikely to be at levels high enough to cause an allergic reaction,[13] due to the presence of such a chemical, quality control and testing are of utmost importance. Flame retardants (mainly in the brominated form) are also of concern where the environment, and their potential toxicity, are concerned.[14] Testing for these additives is possible at a number of commercial laboratories, it is also possible to have textiles tested for according to the Oeko-tex Certification Standard which contains limits levels for the use of certain chemicals in textiles products.

See also

- Bettsometer

- Naraya

- Quipu

- Realia (library science)

- Textile manufacturing

- Textile manufacturing terminology

- Textile preservation

- Textile printing

- Textile recycling

- Timeline of clothing and textiles technology

- Units of textile measurement

- Textiles of Mexico

- Textiles of Oaxaca

References

- ↑ "An Introduction to Textile Terms" (pdf). http://www.textilemuseum.org/PDFs/TextileTerms.pdf. Retrieved August 6, 2006.

- ↑ Balter M. (2009). Clothes Make the (Hu) Man. Science,325(5946):1329.doi:10.1126/science.325_1329a

- ↑ Kvavadze E, Bar-Yosef O, Belfer-Cohen A, Boaretto E,Jakeli N, Matskevich Z, Meshveliani T. (2009).30,000-Year-Old Wild Flax Fibers. Science, 325(5946):1359. doi:10.1126/science.1175404 [/http://worldtextile.aimoo.com/ Supporting Online Material]

- ↑ Keim, Brandon (February 13, 2008). "Piezoelectric Nanowires Turn Fabric Into Power Source". Wired News (CondéNet). http://blog.wired.com/wiredscience/2008/02/piezoelectric-n.html. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ↑ Yong Qin, Xudong Wang & Zhong Lin Wang (October 10, 2007). "Letter/abstract: Microfibre–nanowire hybrid structure for energy scavenging". Nature (Nature Publishing Group) 451 (7180): 809–813. doi:10.1038/nature06601. PMID 18273015. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v451/n7180/full/nature06601.html. Retrieved 2008-02-13. cited in "u Editor's summary: Nanomaterial: power dresser". Nature. Nature Publishing Group. February 14, 2008. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v451/n7180/edsumm/e080214-06.html. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ↑ Euroflax Industries Ltd. "Euroflaxx Industries (Import of Textiles)"

- ↑ Fonte, Diwata (August 23, 2005). "Milk-fabric clothing raises a few eyebrows". The Orange County Register. http://www.textile-technology.com/2010/04/milk-fabric-clothing-raises-a-few-eyebrows/. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- ↑ Art-Gourds.com Traditional Peruvian embroidery production methods

- ↑ Green Inc. Blog "Cutting Water Use in the Textile Industry." The New York Times. July 21, 2009. July 28, 2009.

- ↑ The Materials Science and Engineering of Clothing

- ↑ Lazarov, Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venerology, 2004

- ↑ Lazarov and Cordoba, 2000

- ↑ Scheman et al, Contact Dermatitis, 1998

- ↑ Alaee et al, Environ Int, 2003

Sources

- Good, Irene. 2006. "Textiles as a Medium of Exchange in Third Millennium B.C.E. Western Asia." In: Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World. Edited by Victor H. Mair. University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu. Pages 191-214. ISBN 978-0824828844

- Fisher, Nora (Curator Emirta, Textiles & Costumes), Museum of International Folk Art. "Rio Grande Textiles." Introduction by Teresa Archuleta-Sagel. 196 pages with 125 black and white as well as color plates, Museum of New Mexico Press, Paperbound.

- David H. Abrahams, "Textile chemistry", McGraw Hill Encyclopedia of Science—available in AccessScience@McGraw-Hill, DOI 10.1036/1097-8542.687500, last modified: February 21, 2007. (Subscription access)

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)