Giorgio de Chirico

| Giorgio de Chirico | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Giorgio de Chirico in 1936 photographed by Carl Van Vechten. |

|

| Birth name | Giorgio de Chirico |

| Born | July 10, 1888 Volos, Greece |

| Died | November 20, 1978 Rome, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Field | Painting |

| Training | Academy of Fine Arts in Munich |

| Movement | scuola metafisica, Surrealism |

| Works | see Selected works |

Giorgio de Chirico (Italian pronunciation: [ˈdʒɔrdʒo deˈkiriko]; July 10, 1888 – November 20, 1978) was a pre-Surrealist and then Surrealist Italian painter born in Volos, Greece, to a Genoese mother and a Sicilian father. [1]He founded the scuola metafisica art movement. His surname is traditionally written De Chirico (capitalized De) when it stands alone.

Contents |

Life and works

After studying art in Athens and Florence, De Chirico moved to Germany in 1906 and entered the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, where he read the writings of the philosophers Nietzsche, Arthur Schopenhauer and Otto Weininger and studied the works of Arnold Böcklin and Max Klinger.

He returned to Italy in the summer of 1909 and spent six months in Milan. At the beginning of 1910, he moved to Florence where he painted the first of his 'Metaphysical Town Square' series, The Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon, after the revelation he felt in Piazza Santa Croce. He also painted The Enigma of the Oracle while in Florence. In July 1911 he spent a few days in Turin on his way to Paris. De Chirico was profoundly moved by what he called the 'metaphysical aspect' of Turin: the architecture of its archways and piazzas. It was the city of Nietzsche. De Chirico moved to Paris in July 1911, where he joined his brother Andrea. Through his brother he met Pierre Laprade, a member of the jury at the Salon d'Automne, where he exhibited three of his works Enigma of the Oracle, Enigma of an Afternoon and Self-Portrait. During 1913 he exhibited his work at the Salon des Indépendants and Salon d’Automne, his work was noticed by Pablo Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire, he also sold his first painting, The Red Tower. In 1914 through Guillaume Apollinaire, he met the art dealer Paul Guillaume, with whom he signed a contract for his artistic output.

At the outbreak of the First World War, he returned to Italy. Upon his arrival in May 1915 he enlisted in the Italian army, but he was considered unfit for work and assigned to the hospital at Ferrara. He continued to paint, and in 1918, he transferred to Rome. From 1918 his work was exhibited extensively in Europe.

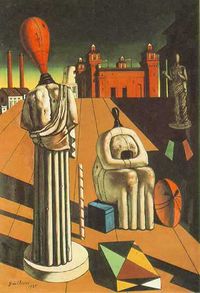

De Chirico is best known for the paintings he produced between 1909 and 1919, his metaphysical period, which are memorable for the haunted, brooding moods evoked by their images. At the start of this period, his subjects were still cityscapes inspired by the bright daylight of Mediterranean cities, but gradually he turned his attention to studies of cluttered storerooms, sometimes inhabited by mannequin-like hybrid figures.

In autumn 1919 De Chirico published an article in Valori Plastici entitled "The Return of Craftsmanship", in which he advocated a return to traditional methods and iconography.[2] This article heralded an abrupt change in his artistic orientation, as he adopted a classicizing manner inspired by such old masters as Raphael and Signorelli, and became an outspoken opponent of modern art.[3]

De Chirico met and married his first wife, the Russian Ballerina Raissa Gurievich in 1924, and together they moved to Paris. In 1928 he held his first exhibition in New York City and shortly afterwards, London. He wrote essays on art and other subjects, and in 1929 published a novel entitled Hebdomeros, the Metaphysician.

In 1930 De Chirico met his second wife, Isabella Pakszwer Far, a Russian, with whom he would remain for the rest of his life. Together they moved to Italy in 1932, finally settling in Rome in 1944.

In 1939 he adopted a neo-Baroque style influenced by Rubens.[4] De Chirico's later paintings never received the same critical praise as did those from his metaphysical period. He resented this, as he thought his later work was better and more mature. He produced backdated "self-forgeries" both to profit from his earlier success, and as an act of revenge—retribution for the critical preference for his early work.[5] He also denounced many paintings attributed to him in public and private collections as forgeries.[6]

He remained extremely prolific even as he approached his 90th year.[7] In 1974 he was elected to the French Académie des Beaux-Arts. He died in Rome on November 20, 1978.

His brother, Andrea de Chirico, who became famous as Alberto Savinio, was also a writer and a painter.

Legacy

De Chirico won praise for his work almost immediately from writer Guillaume Apollinaire, who helped to introduce his work to the later Surrealists.

Yves Tanguy wrote how one day in 1922 he saw one of De Chirico's paintings in an art dealer's window, and was so impressed by it he resolved on the spot to become an artist — although he had never even held a brush. Other artists who acknowledged De Chirico's influence include Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, Giorgio Morandi, Carlo Carrà, René Magritte, and Philip Guston. De Chirico strongly influenced the Surrealist movement.

'That de Chirico was a poet, and a great one, is not in dispute. He could condense voluminous feeling through metaphor and association. One can try to dissect these magical nodes of experience, yet not find what makes them cohere... Early de Chiricos are full of such effects. Et quid amabo nisi quod aenigma est? ("What shall I love if not the enigma?")—this question, inscribed by the young artist on his self-portrait in 1911, is their subtext.'[3] (In this, he resembles his more representational American contemporary, Edward Hopper: their pictures' low sunlight, their deep and often irrational shadows, their empty walkways and portentous silences creating an enigmatic visual poetry.) [8]

The visual style of Valerio Zurlini's film The Desert of the Tartars (1976) was influenced by De Chirico's work.[9] Michelangelo Antonioni, the Italian film director, also claimed to be influenced by De Chirico. Some comparison can be made to the long takes in Antonioni's films from the 1960s, in which the camera continues to linger on desolate cityscapes populated by a few distant figures, or none at all, in the absence of the film's protagonists.

Modern photographer Duane Michals was also influenced by De Chirico.

Writers who have apreciated De Chirico include John Ashbery, who has called Hebdomeros "probably...the finest [major work of Surrealist fiction]." [10] Several of Sylvia Plath's poems are influenced by De Chirico. In his book Blizzard of One Mark Strand included a poetic diptych called "Two de Chiricos:" "The Philosopher's Conquest" and "The Disquieting Muses."

Fumito Ueda's critically acclaimed PlayStation 2 game Ico (and also its sequel, Shadow of the Colossus, in a less direct way) was strongly influenced by De Chirico. Ico features children wandering though huge, ancient and otherwise uninhabited buildings, are predominately yellow and green in colour and use music only for cut-scenes, enhancing the feeling of space and sparseness. The box art for Ico used in Japan and Europe is particularly imitative of De Chirico's Melancholy and Mystery of a Street and The Nostalgia of the Infinite (both 1914).

Selected works

- Flight of the Centauri, Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon and Enigma of the Oracle (1909)

- Ritratto di Andrea de Chirico (Alias Alberto Savinio) (1909–1910)

- Enigma of the Hour (1911)

- Melanconia, The Enigma of the Arrival and La Matinèe Angoissante (1912)

- The Red Tower, Ariadne, The Awakening of Ariadne, The Uncertainty of the Poet, La Statua Silenziosa, The Anxious Journey, Melancholy of a Beautiful Day, Le Rêve Transformé, and Self-Portrait (1913)

- The Anguish of Departure (begun in 1913), Portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire, The Nostalgia of the Poet, L'Énigme de la fatalité, Gare Montparnasse (The Melancholy of Departure), Love Song, The Enigma of a Day, The Philosopher’s Conquest, The Child’s Brain, The Philosopher and the Poet, Still Life: Turin in Spring, Piazza d’Italia (Autumn Melancholy), The Nostalgia of the Infinite and Melancholy and Mystery of a Street (1914)

- The Evil Genius of a King (begun in 1914), The Seer (or The Prophet), Piazza d’Italia, The Double Dream of Spring, The Purity of a Dream, Two Sisters (The Jewish Angel) and The Duo (1915)

- Andromache, The Melancholy of Departure, The Disquieting Muses, Metaphysical Interior with Biscuits (1916)

- Metaphysical Interior with Large Factory and The Faithful Servitor (both began in 1916), The Great Metaphysician, Ettore e Andromaca, Metaphysical Interior, Geometric Composition with Landscape and Factory and Great Metaphysical Interior (1917)

- Metaphysical Muses and Hermetic Melancholy (1918)

- Still Life with Salami and The Sacred Fish (1919)

- Self-portrait (1920)

- Italian Piazza, Maschere and Departure of the Argonauts (1921)

- The Prodigal Son (1922)

- Florentine Still Life (c. 1923)

- The House with the Green Shutters (1924)

- The Great Machine (1925) Honolulu Academy of Arts

- Au Bord de la Mer, Le Grand Automate, The Terrible Games, Mannequins on the Seashore and The Painter (1925)

- La Commedia e la Tragedia (Commedia Romana), The Painter’s Family and Cupboards in a Valley (1926)

- L’Esprit de Domination, The Eventuality of Destiny (Monumental Figures), Mobili nella valle and The Archaeologists (1927)

- Temple et Forêt dans la Chambre (1928)

- Gladiatori (began in 1927), The Archaeologists IV (from the series Metamorphosis), The return of the Prodigal son I (from the series Metamorphosis) and Bagnante (Ritratto di Raissa) (1929)

- Illustrations from the book Calligrammes by Guillaume Apollinaire (1930)

- I Gladiatori (Combattimento) (1931)

- Cavalos a Beira-Mar (1932–1933)

- Cavalli in Riva al Mare (1934)

- La Vasca di Bagni Misteriosi (1936)

- The Vexations of The Thinker (1937)

- Self-portrait (1935–1937)

- Archeologi (1940)

- Illustrations from the book L’Apocalisse (1941)

- Portrait of Clarice Lispector (1945)

- Villa Medici - Temple and Statue (1945)

- Minerva (1947)

- Metaphysical Interior with Workshop (1948)

- Fiat (1950)

- Piazza d’Italia (1952)

- The Fall - Via Crucis (1947–54)

- Venezia, Isola di San Giorgio (1955)

- Salambò su un cavallo impennato (1956)

- Metaphysical Interior with Biscuits (1958)

- Piazza d’Italia (1962)

- Cornipedes, (1963)

- Manichino (1964)

- Ettore e Andromaca (1966)

- The Return of Ulysses, Interno Metafisico con Nudo Anatomico and Mysterious Baths - Flight Toward the Sea (1968)

- Il rimorso di Oreste, La Biga Invincibile and Solitudine della Gente di Circo (1969)

- Orfeo Trovatore Stanco, Intero Metafisico and Muse with Broken Column (1970)

- Metaphysical Interior with Setting Sun (1971)

- Sole sul cavalletto (1972)

- Mobili e rocce in una stanza, La Mattina ai Bagni misteriosi, Piazza d'Italia con Statua Equestre, La mattina ai bagni misteriosi and Ettore e Andoromaca (1973)

- Pianto d’amore - Ettore e Andromaca and The Sailors’ Barracks (1974)

Works about

- Aenigma Est – 1990 film (Direction: Dimitri Mavrikios; Screenplay: Thomas Moschopoulos, Dimitri Mavrikios)

References

- ↑ Metropolitan Museum of Art brief biographyRetrieved September 6, 2010

- ↑ Holzhey, Magdalena. Giorgio de Chirico. Cologne: Taschen, 2005, p. 60. ISBN 3822841528

- ↑ Schwartz, Sanford. Artists and Writers. New York: Yarrow Press, 1990, pp. 28–29. ISBN 1-878274-01-5

- ↑ Holzhey 2005, p. 94.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Schwartz 1990, p. 29.

- ↑ Wells, Walter, Silent Theater: the Art of Edward Hopper, London/New York: Phaidon, 2007

- ↑ Rolando Caputo. Literary cineastes: the Italian novel and the cinema. In: Peter E. Bondanella & Andrea Ciccarelli (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to the Italian Novel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. P. 182-196.

- ↑ Selected Prose, p 89. (Originally in Book Week 4:15 (Dec. 18, 1966))