Giovanni Bellini

| Giovanni Bellini | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait |

|

| Born | 1430 Venice |

| Died | 1516 (aged 85–86) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Field | Painting |

| Movement | Renaissance |

Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430–1516[1]) was an Italian Renaissance painter, probably the best known of the Bellini family of Venetian painters. His father was Jacopo Bellini, his brother was Gentile Bellini, and his brother-in-law was Andrea Mantegna. He is considered to have revolutionized Venetian painting, moving it towards a more sensuous and colouristic style. Through the use of clear, slow-drying oil paints, Giovanni created deep, rich tints and detailed shadings. His sumptuous coloring and fluent, atmospheric landscapes had a great effect on the Venetian painting school, especially on his pupils Giorgione and Titian.

Contents |

Early career

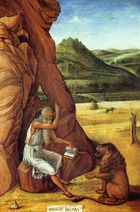

Giovanni Bellini was born in Venice. He was brought up in his father's house, and always lived and worked in the closest fraternal relation with his brother Gentile. Up until the age of nearly thirty we find in his work a depth of religious feeling and human pathos which is his own. His paintings from the early period are all executed in the old tempera method; the scene is softened by a new and beautiful effect of romantic sunrise color (see for example, the St. Jerome at left).

In a somewhat changed and more personal manner, with less harshness of contour and a broader treatment of forms and draperies, but not less force of religious feeling, are the Dead Christ pictures, in these days one of the master's most frequent themes, (see for example the Pietà: Dead Christ Supported by the Virgin and St. John at right). Giovanni's early works have often been linked both compositionally and stylistically to those of his brother-in-law, Andrea Mantegna (1431–1506).

In 1470 Giovanni received his first appointment to work along with his brother and other artists in the Scuola di San Marco, where among other subjects he was commissioned to paint a Deluge with Noah's Ark. None of the master's works of this kind, whether painted for the various schools or confraternities or for the ducal palace, have survived.

Maturity

To the decade following 1470 must probably be assigned the Transfiguration (at right) now in the Naples museum, repeating with greatly ripened powers and in a much serener spirit the subject of his early effort at Venice.

Also the great altar-piece of the Coronation of the Virgin at Pesaro, which would seem to be his earliest effort in a form of art previously almost monopolized in Venice by the rival school of the Vivarini.

As is the case with a number of his brother, Gentile's public works of the period, many of Giovanni's great public works are now lost. The still more famous altar-piece painted in tempera for a chapel in the church of S. Giovanni e Paolo, where it perished along with Titian's Peter Martyr and Tintoretto's Crucifixion in the disastrous fire of 1867.

After 1479–1480 much of Giovanni's time and energy must also have been taken up by his duties as conservator of the paintings in the great hall of the ducal palace. The importance of this commission can be measured by the payment Giovanni received: he was awarded, first the reversion of a broker's place in the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, and afterwards, as a substitute, a fixed annual pension of eighty ducats. Besides repairing and renewing the works of his predecessors he was commissioned to paint a number of new subjects, six or seven in all, in further illustration of the part played by Venice in the wars of Frederick Barbarossa and the pope. These works, executed with much interruption and delay, were the object of universal admiration while they lasted, but not a trace of them survived the fire of 1577; neither have any other examples of his historical and processional compositions come down, enabling us to compare his manner in such subjects with that of his brother Gentile.

Of the other, the religious class of his work, including both altar-pieces with many figures and simple Madonnas, a considerable number have fortunately been preserved. They show him gradually throwing off the last restraints of the Quattrocento manner; gradually acquiring a complete mastery of the new oil medium introduced in Venice by Antonello da Messina about 1473, and mastering with its help all, or nearly all, the secrets of the perfect fusion of colors and atmospheric gradation of tones. The old intensity of pathetic and devout feeling gradually fades away and gives place to a noble, if more worldly, serenity and charm. The enthroned Virgin and Child (such as the one at left) become tranquil and commanding in their sweetness; the personages of the attendant saints gain in power, presence and individuality; enchanting groups of singing and viol-playing angels symbolize and complete the harmony of the scene. The full splendour of Venetian color invests alike the figures, their architectural framework, the landscape and the sky.

High Renaissance

An interval of some years, no doubt chiefly occupied with work in the Hall of the Great Council, seems to separate the San Giobbe Altarpiece (at left), and that of the church of San Zaccaria at Venice (at right). Formally, the works are very similar, so a comparison between serves to illustrate the shift in Bellini's work over the last decade of the Quattrocento. Both pictures are of the Sacra conversazione (sacred conversation between the Madonna and Saints) type. Both show the Madonna seated on a throne (thought to allude to the throne of Solomon), between classicizing columns. Both place the holy figures beneath a golden mosaicked half dome that recalls the Byzantine architecture in the church of San Marco.

In the later work he depicts the Virgin surrounded by (from left): St. Peter holding his keys and the Book of Wisdom; the virginal St. Catherine and St. Lucy closest to the Virgin, each holding a martyr's palm and her implement of torture (Catherine a breaking wheel, and Lucy a dish with her eyes); St. Jerome, who translated the Greek Bible into the first Latin edition (the Vulgate).

Stylistically, the lighting in the San Zaccaria piece has become so soft and diffuse that it makes that in the San Giobbe appear almost raking in contrast. Giovanni's use of the oil medium had matured, and the holy figures seem to be swathed in a still, rarefied air. The San Zaccaria is considered perhaps the most beautiful and imposing of all Giovanni's altarpieces, and is dated 1505, the year following that of Giorgione's Madonna of Castelfranco.

Other late altar-piece with saints include that of the church of San Francesco della Vigna at Venice, 1507; that of La Corona at Vicenza, a Baptism of Christ in a landscape, 1510; and that of San Giovanni Crisostomo at Venice of 1513.

Of Giovanni's activity in the interval between the altar-pieces of San Giobbe and San Zaccaria, there are a few minor works left, though the great mass of his output perished with the fire of the Doge's Palace in 1577. The last ten or twelve years of the master's life saw him besieged with more commissions than he could well complete. Already in the years 1501–1504 the marchioness Isabella Gonzaga of Mantua had had great difficulty in obtaining delivery from him of a picture of the Madonna and Saints (now lost) for which part payment had been made in advance. In 1505 she endeavoured through Cardinal Bembo to obtain from him another picture, this time of a secular or mythological character. What the subject of this piece was, or whether it was actually delivered, we do not know.

Albrecht Dürer, visiting Venice for a second time in 1506, describes Giovanni Bellini as still the best painter in the city, and as full of all courtesy and generosity towards foreign brethren of the brush.

In 1507 Bellini's brother Gentile died, and Giovanni completed the picture of the Preaching of St. Mark which he had left unfinished; a task on the fulfillment of which the bequest by the elder brother to the younger of their father's sketch-book had been made conditional.

In 1513 Giovanni's position as sole master (since the death of his brother and of Alvise Vivarini) in charge of the paintings in the Hall of the Great Council was threatened by one of his former pupils. Young Titian desired a share of the same undertaking, to be paid for on the same terms. Titian's application was granted, then after a year rescinded, and then after another year or two granted again; and the aged master must no doubt have undergone some annoyance from his sometime pupil's proceedings. In 1514 Giovanni undertook to paint The Feast of the Gods for the duke Alfonso I of Ferrara, but died in 1516.

He was interred in the Basilica di San Giovanni e Paolo, a traditional burial place of the doges.

Assessment

Both in the artistic and in the worldly sense, the career of Giovanni Bellini was, on the whole, very prosperous. His long career began with Quattrocento styles but matured into the progressive post-Giorgione Renaissance styles. He lived to see his own school far outshine that of his rivals, the Vivarini of Murano; he embodied, with growing and maturing power, all the devotional gravity and much also of the worldly splendour of the Venice of his time; and he saw his influence propagated by a host of pupils, two of whom at least, Giorgione and Titian, equalled or even surpassed their master. Giorgione he outlived by five years; Titian, as we have seen, challenged him, claiming an equal place beside his teacher. Other pupils of the Bellini studio included Girolamo da Santacroce, Vittore Belliniano, Rocco Marconi, Andrea Previtali[5] and possibly Bernardino Licinio.

In the historical perspective, Bellini was essential to the development of the Italian Renaissance for his incorporation of aesthetics from Northern Europe. Significantly influenced by Antonello da Messina, who had spent time in Flanders, Bellini made prevalent both the use of oil painting, different from the tempera painting being used at the time by most Italian Renaissance painters, and the use of disguised symbolism integral to the Northern Renaissance. As demonstrated in such works as St. Francis in Ecstasy (c. 1480, at left) and the San Giobbe Altarpiece (c. 1478), Bellini makes use of religious symbolism through natural elements, such as grapevines and rocks. Yet his most important contribution to art lies in his experimentation with the use of color and atmosphere in oil painting.

Works

- Madonna with Child (1450–1555) - Tempera on wood, 47 x 31.5 cm, Civico Museo Malaspina, Pavia [2]

- Madonna with Child (c. 1455) - Tempera on panel, 72 x 46 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York[3]

- Dead Christ Supported by the Madonna and St. John (1455) - Tempera on wood, 52 x 42 cm, Accademia Carrara, Bergamo[4]

- Crucifixion (c. 1455) - Tempera on wood, 54.5 x 30 cm, Museo Correr, Venice[5]

- Transfiguration (c. 1455–1460) - Tempera on panel, 134 x 68 cm, Museo Correr, Venice [6]

- Agony in the Garden (c. 1459) - Tempera on wood, 81 x 127 cm, National Gallery, London[7]

- Dead Christ Supported by the Madonna and St. John (1460) - Tempera on panel, 86 x 107 cm, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan[8]

- Dead Christ Supported by Two Angels (Pietà, c. 1460) - Tempera on panel, 74 x 50 cm, Museo Correr, Venice[9]

- Dead Christ in the Sepulchre (c. 1460) - Tempera on panel, 48 x 38 cm, Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan[10]

- Blessing Christ (c. 1460) - Tempera on wood, 58 x 44 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris[11]

- The Blood of Christ (c. 1460) - Tempera on panel, 134 x 68 cm, National Gallery, London

- Madonna and Child (1460–1464) - Tempera on panel, 78 x 54 cm, Civiche Raccolte d'Arte, Milan[12]

- Madonna with Child Blessing (1460–1464) - Tempera on wood, 79 x 63 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice[13]

- Madonna with Child (Greek Madonna, 1460–1464) - Tempera on wood, 82 x 62 cm, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan[14]

- Madonna and Child (1460–1464) - Oil on canvas transferred from wood, 52 x 42.5 cm, Museo Correr, Venice[15]

- Madonna and Child (1460–1464) - Tempera on panel, 47 x 34 cm, Accademia Carrara, Bergamo[16]

- Presentation at the Temple (1460–1464) - Tempera on wood, 80 x 105 cm, Galleria Querini Stampalia, Venice[17]

- St. Sebastian Triptych (1460–1464) - Tempera on panel, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice[18]

- Nativity Triptych (1460–1464) - Tempera on panel, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice[19]

- Head of the Baptist (1464–1468) - Tempera on wood, diameter 28 cm, Musei Civici, Pesaro[20]

- Polyptych of S. Vincenzo Ferreri (1464–1468) - Tempera on panel, Basilica dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo, Venice

- Pesaro Altarpiece (1471–1474) - Oil on panel, 262 x 240 cm, Musei Civici, Pesaro

- Pietà (1472) - Tempera on canvas, 115 x 317 cm, Doge's Palace, Venice[21]

- Dead Christ Supported by Angels (Bellini)Dead Christ Supported by Angels (c. 1474) - Tempera on panel, 91 x 131 cm, Pinacoteca Comunale, Rimini[22]

- Madonna Enthroned Adoring the Sleeping Child (1475) - Tempera on wood, 120 x 65 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice[23]

- Madonna with Child (c. 1475) - Tempera on panel, 77 x 57 cm, Museo di Castelvecchio, Verona[24]

- Madonna with Child (c. 1475) - Tempera on panel, 75 x 50 cm, Santa Maria dell'Orto, Venice[25]

- Madonna in Adoration of the Sleeping Child (c. 1475) - Tempera on panel, 77 x 56 cm, Contini Bonacossi Collection, Florence[26]

- Madonna with Blessing Child (1475–1480) Oil on panel, 78 x 56 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice[27]

- Portrait of a Humanist (1475–1480) - Oil on panel, 35 x 28 cm, Civiche Raccolte d'Arte, Milan

- Resurrection of Christ (1475–1479) - Oil on panel, 148 x 128 cm, Staatliche Museen, Berlin

- St. Francis in Ecstasy (c. 1480) - Oil on panel, 124 x 142 cm, Frick Collection, New York, United States

- Transfiguration of Christ (c. 1480) - Oil on panel, 116 x 154 cm, Museo di Capodimonte, Naples

- St. Jerome Reading in the Countryside (1480–1485) - Oil on wood, 47 x 34 cm, National Gallery, London

- Madonna Willys (1480–1490) - Oil on panel, 75 x 59 cm, São Paulo Museum of Art, São Paulo, Brazil

- Madonna and Child (1480–1490) - Oil on panel, 83 x 66 cm, Accademia Carrara, Bergamo

- Madonna of Red Angels (1480–1490) - Oil on panel, 77 x 60 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

- Portrait of a Condottiero - Oil on wood, 51 x 37 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington

- Portrait of a Young Man in Red (1485–1490) - Oil on panel, 32 x 26 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington

- Madonna degli Alberetti (1487) - Oil on panel, 74 x 58 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

- Madonna and Child (1485–1490) - Oil on panel, 88.9 x 71.1 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- San Giobbe Altarpiece (c. 1487) - Oil on panel, 471 x 258 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

- Madonna with Child and Sts. Peter and Sebastian (c. 1487) - Oil on panel, 84 x 61 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

- Frari Triptych (1488) - Oil on panel, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice

- Barbarigo Altarpiece (1488) - Oil on canvas, 200 x 320 cm, San Pietro Martire, Murano

- Sacred Conversation (1490) - Oil on panel, 77 x 104 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Allegories (c. 1490) - Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

- Sacred Conversation (c. 1490) - Oil on wood, 58 x 107 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

- Holy Allegory (c. 1490) - Oil on panel, 73 x 199 cm, Uffizi, Florence

- The Lamentation over the Body of Christ (c. 1500) - Tempera on wood, 76 x 121 cm, Uffizi, Florence

- Angel Announcing and Virgin Announciated (c. 1500) - Oil on canvas, 224 x 105 cm (each), Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

- Portrait of a Young Man (c. 1500) - Oil on panel, 32 x 26 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

- Portrait of a Young Man (c. 1500) - Oil on wood, 31 x 25 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington

- Portrait of a Young Senator (1500) - Oil on wood, 31 x 26 cm, Uffizi, Florence

- Portrait of Doge Leonardo Loredan (1501) - Oil on panel, 61.5 x 45 cm, National Gallery, London

- Baptism of Christ (1500–1502) - Oil on canvas, 400 x 263 cm, Santa Corona, Vicenza

- Head of the Redeemer (1500–1502) - Oil on panel, 33 x 22 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

- Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist and a Saint (1500–1504) - Oil on panel, 54 x 76 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

- Crucifixion (1501–1503) - Oil on panel, 81 x 49 cm, The Albert Gallery, Prato

- Sermon of St. Mark in Alexandria (1504–1507) - Oil on canvas, 347 x 770 cm, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

- Holy Conversation (1505–1510) - Oil on panel, 62 x 83 cm, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid

- San Zaccaria Altarpiece (1505) - Oil on canvas transferred from wood, 402 x 273 cm, San Zaccaria, Venice

- Madonna of the Meadow (Madonna del Prato; 1505) - Oil on canvas transferred from wood, 67 x 86 cm, National Gallery, London

- Pietà (1505) - Oil on wood, 65 x 90 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

- St. Jerome in the Desert (1505) - oil on panel, 49 x 39 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington

- The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr (1507) - Egg tempera and oil on wood, 99.7 x 165.1 cm, National Gallery, London

- Madonna and Child with Four Saints and Donator (1507) - Oil on wood, 90 x 145 cm, San Francesco della Vigna, Venice

- Continence of Scipio (1507–1508) - Oil on canvas, 74.8 x 35.6 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington

- The Murder of St. Peter the Martyr (1509) - Oil on panel, 67.3 x 100.4 cm, Courtauld Institute Galleries, London

- Madonna and Child Blessing (1510) - Oil on wood, 85 x 118 cm, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan[28]

- Madonna with Child (c. 1510) - Oil on wood, 50 x 41 cm, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- Saints Christopher, Jerome and Louis of Toulouse (1513) - Oil on panel, 300 x 185 cm, S. Giovanni Crisostomo, Venice

- Feast of the Gods (1514) - Oil on cavas, 170 x 188 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington

- Young Bacchus (c. 1514) - Oil on wood, 48 x 37 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington

- Naked Young Woman in Front of the Mirror (1515) - Oil on canvas, 62 x 79 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- Portrait of Teodoro of Urbino (1515) - Oil on canvas, 63 x 49.5 cm, National Gallery, London

- Deposition (c. 1515) - Oil on canvas, 444 x 312 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

- Drunkennes of Noah (c. 1515) - Oil on canvas, 103 x 157 cm, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Besançon

References

- ↑ His precise date of death is not recorded, but he was known to have died by 29 November 1516 - [1]

- ↑ The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, the Lapworth Museum of Geology and the University of Birmingham Collections - Objects

- ↑ The Feast of the Gods

- ↑ The Frick Collection

- ↑ S.J. Freedberg, p 171

Further reading

- Oskar Batschmann, Giovanni Bellini (London, Reaktion Books, 2008).