Gurkha

Gurkha, also spelled as Gorkha or Ghurka (Nepali: गोर्खा), are people from Nepal and northern India[1] who take their name from the 8th century Hindu warrior-saint Guru Gorakhnath.[2] His disciple Bappa Rawal, born Prince Kalbhoj/Prince Shailadhish, founded the house of Mewar, Rajasthan (Rajputana). Later descendants of Bappa Rawal moved further east to found the house of Gorkha, which in turn founded the Kingdom of Nepal.[2] Gorkha District is one of the 75 districts of modern Nepal.

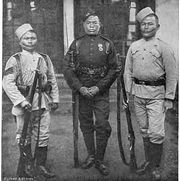

Gurkhas are best known for their history of bravery and strength in the Indian Army's Gorkha regiments and the British Army's Brigade of Gurkhas. The Gurkhas were designated by British officials as a "Martial Race". "Martial Race" was a designation created by officials of British India to describe "races" (peoples) that were thought to be naturally warlike and aggressive in battle, and to possess qualities of courage, loyalty, self sufficiency, physical strength, resilience, orderliness, the ability to work hard for long periods of time, fighting tenacity and military strategy. The British recruited heavily from these Martial Races for service in the British Indian Army.[3]

Former Chief of staff of the Indian Army, Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw once famously said about Gurkhas:

| “ | If a man says he is not afraid of dying, he is either lying or is a Gurkha. | ” |

Etymology

The word Gorkha is derived from the Prakrit words "go rakkha" (Sanskrit gau-rakṣa, literally "cow-protector"). This was used by Guru Gorakhnath, the spiritual leader of the Gorkhas, the name given to his disciples.

History

Gurkhas claim descent from the Hindu Rajputs of Northern India, who entered modern Nepal from the west. Guru Gorkhanath had a Rajput Prince-disciple, the legendary Bappa Rawal, born Prince Kalbhoj/Prince Shailadhish, founder of the Royal house of Mewar, who became the first Gurkha and is said to be the ancestor of the Royal family of Nepal.[2]

The majority of the early Gurkhas were from the Thakuri/Rajput (which includes the Shah dynasty and Rana dynasty of Nepal), Chetri and Brahmin ethnic groups, whereas the modern Gurkha soldiers are also from the Limbu, Rai, Gurung and Magar ethnic groups. They joined the Gurkhas during 17th century expansion of the Gurkha kingdom.[4] However, even today the Thakuris and Chetris make up the majority of Gurkha officers in Nepal, while the Gurkha army also have Limbu, Rai, Gurung and Magar people, this combination of warriors from different ethnic groups made the Gurkhas a dominant military force in the history of the Indian subcontinent since the 18th century.

The legend states that Bappa Rawal was a teenager in hiding, when he came upon the warrior saint while on a hunting expedition with friends in the jungles of Rajasthan. Bappa Rawal chose to stay behind, and care for the warrior saint, who was in deep meditation. When Guru Gorkhanath awoke, he was pleased with the devotion of Bappa Rawal. The Guru gave him the Kukri (Khukuri) knife, the famous curved blade of the present day Gurkhas.[5] The legend continues that he told Bappa that he and his people would henceforth be called Gurkhas, the disciples of the Guru Gorkhanath, and their bravery would become world famous. He then instructed Bappa Rawal, and his Gurkhas to stop the advance of the Muslims, who were invading Afghanistan (which at that time was a Hindu/Buddhist nation). Bappa Rawal took his Gurkhas and liberated Afghanistan — originally named Gandhara, from which the present day Kandahar derives its name. He and his Gurkhas stopped the initial Islamic advance of the 8th century in the Indian subcontinent.[2]

There are legends that Bappa Rawal (Kalbhoj) went further conquering Iran and Iraq before he retired as an ascetic at the feet of Mt. Meru, having conquered all invaders and enemies of his faith.

It is a misconception that the Gurkhas took their name from the Gorkha region of Nepal. The region was given its name after the Gurkhas had established their control of these areas.[5] In the early 16th century some of Bappa Rawal's descendants went further east, and conquered a small state in present-day Nepal, which they named Gorkha in honour of their patron saint. By 1769, through the leadership of Sri Panch (5) Maharaj Dhiraj Prithvi Narayan Shahdev (1769–1775), the Gorkha dynasty had taken over the area of modern Nepal. They made Hinduism the state religion, although with distinct Rajput warrior and Gorkhanath influences.

In the Gurkha War (1814–1816) they waged war against the British East India Company army. The British were impressed by the Gurkha soldiers and after reaching a stalemate with the Gurkhas made Nepal a protectorate.[6] Much later, they were granted the right to freely hire them as mercenaries from the interior of Nepal (as opposed to the early British Gurkha mercenaries who were hired from areas such as Assam (i.e., the Sirmoor Rifles) and were then organised in Gurkha regiments in the East India Company army with the permission of then prime minister, Shree Teen (3) Maharaja (Maharana) Jung Bahadur Rana, the first Rana Prime-minister who initiated a Rana oligarchic rule in Nepal. Jung Bahadur was the grandson of the famous Nepalese hero and Prime minister Bhimsen Thapa. Originally Jung Bahadur and his brother Ranodip Singh brought a lot of modernisation to Nepalese society, the abolition of slavery, undermining of taboos regarding the untouchable class, public access to education, etc. But these dreams were short lived when in the coup d'état of 1885 the nephews of Jung Bahadur and Ranodip Singh (the Shumshers J.B., S.J.B. or Satra (17) Family) murdered Ranodip Singh and the sons of Jung Bahadur, stole the name of Jung Bahadur and took control of Nepal.[2][6] This "Shumsher" Rana rule is regarded by some as one of the reasons for Nepal lagging behind in modern development. The children of Jung Bahadur and Ranodip Singh lived mainly outside of Kathmandu, in Nepal, and in India after escaping the coup d'état of 1885.[6]

The "original" Gurkhas who were descended from the Rajputs (Thakuri and Chetri) refused to enter as soldiers and were instead given positions as officers in the British-Indian armed forces. The non-Kashaktriya Gurkhas entered as soldiers (i.e., Magar, Gurung). The Thakur/Rajput Gurkhas were entered as officers, one of whom, (retired) General Narendra Bahadur Singh, Gurkha Rifles, great grandson of Jung Bahadur, while a young captain, rose to become aide-de-camp (A.D.C.) to Lord Mountbatten of Burma, the last Viceroy of India.[2]

The Gurkha soldier recruits were mainly drawn from several ethnic groups. When the British began recruiting from the interior of Nepal these soldiers were mainly drawn from Magar, Gurung, Rai and Limbu, although earlier British Gurkhas included Garhwalis, Kumaonis, Assamese and others as well.[2]

After the British left India, Gorkhalis continued seeking employment in British and Indian forces, as officers and soldiers. Under international law, present-day British Gurkhas are not treated as mercenaries but are fully integrated soldiers of the British Army, operate in formed units of the Brigade of Gurkhas, and abide by the rules and regulations under which all British soldiers serve.

The Gurkha war cry is "Jai Mahakali, Ayo Gorkhali" which literally translates to "Glory be to the Goddess of War, here come the Gorkhas!"

Professor Sir Ralph Turner, MC, who served with the 3rd Queen Alexandra's Own Gurkha Rifles in the First World War, wrote of Gurkhas:

| “ | As I write these last words, my thoughts return to you who were my comrades, the stubborn and indomitable peasants of Nepal. Once more I hear the laughter with which you greeted every hardship. Once more I see you in your bivouacs or about your fires, on forced march or in the trenches, now shivering with wet and cold, now scorched by a pitiless and burning sun. Uncomplaining you endure hunger and thirst and wounds; and at the last your unwavering lines disappear into the smoke and wrath of battle. Bravest of the brave, most generous of the generous, never had country more faithful friends than you. | ” |

British East India Company Army

Gurkhas served as troops under contract to the East India Company in the Pindaree War of 1817, in Bharatpur in 1826 and the First and Second Anglo-Sikh Wars in 1846 and 1848.

During the Indian Rebellion of 1857, Gurkhas fought on the British side, and became part of the British Indian Army on its formation. The 2nd Gurkha Rifles (The Sirmoor Rifles) made a particularly notable contribution during the conflict, and indeed twenty-five Indian Order of Merit awards were made to men from that regiment during the Siege of Delhi.[7] Three days after the mutiny began, the Sirmoor Rifles were ordered to move to Meerut, where the British garrison was barely holding on, and in doing so they had to march up to 48 kilometres a day.[8] Later, during the four month Siege of Delhi they defended Hindu Rao's house, losing 327 out of 490 men. Twelve regiments from the Nepalese Army also took part in the relief of Lucknow[9] under the command of Shri Teen (3) Maharaja Maharana Jung Bahadur of Nepal and his older brother C-in-C Ranaudip Singh (Ranodip or Ranodeep) Bahadur Rana (later to succeed Jung Bahadur and become Sri Teen Maharaja Ranodip Singh of Nepal).

British Indian Army (c. 1857–1947)

From the end of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 until the start of the First World War the Gurkha Regiments saw active service in Burma, Afghanistan, the North-East and the North-West Frontiers of India, Malta (the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–78), Cyprus, Malaya, China (the Boxer Rebellion of 1900) and Tibet (Younghusband's Expedition of 1905).

Between 1901 and 1906, the Gurkha regiments were renumbered from the 1st to the 10th and redesignated as the Gurkha Rifles. In this time, the Brigade of Gurkhas, as the regiments came to be collectively known, was expanded to twenty battalions within the ten regiments.[10]

During World War I (1914–18), more than 200,000 Gurkhas served in the British Army, suffering approximately 20,000 casualties, and receiving almost 2,000 gallantry awards.[11] The number of Gurkha battalions was increased to thirty-three, and Gurkha units were placed at the disposal of the British high command by the Nepalese government for service on all fronts. Many Nepalese volunteers served in noncombat roles, serving in units such as the Army Bearer Corps and the labour battalions, but there were also large numbers that served in combat in France, Turkey, Palestine, and Mesopotamia.[12] They served on the battlefields of France in the Loos, Givenchy, Neuve Chapelle and Ypres; in Mesopotamia, Persia, Suez Canal and Palestine against Turkish advance, Gallipoli and Salonika.[13] One detachment served with Lawrence of Arabia, while during the Battle of Loos (June-December 1915) a battalion of the 8th Gurkhas fought to the last man, hurling themselves time after time against the weight of the German defences, and in the words of the Indian Corps commander, Lieutenant-General Sir James Willcocks, "... found its Valhalla".[14] During the ultimately unsuccessful Gallipoli campaign in 1915, the Gurkhas were among the first to arrive and the last to leave. The 1st/6th Gurkhas, having landed at Cape Helles, led the assault during the first major operation to take out a Turkish high point, and in doing so captured a feature that later became known as "Gurkha Bluff".[15] At Sari Bair they were the only troops in the whole campaign to reach and hold the crest line and look down on the Straits, which was the ultimate objective.[16] The 2nd Battalion of the 3rd Gurkha Rifles (2nd/3rd Gurkha Rifles) was involved in the conquest of Baghdad.

Following the end of the war, the Gurkhas were returned to India and during the interwar years, they were largely kept away from the internal strife and urban conflicts of the sub-continent, instead being employed largely on the frontiers and in the hills where fiercely independent tribesmen were a constant source of troubles.[17]. As such, between the World Wars, the Gurkha regiments fought in the Third Afghan War in 1919 and then participated in numerous campaigns on the North-West Frontier, mainly in Waziristan, where they were employed as garrison troops defending the frontier, keeping the peace amongst the local populace and keeping the lawless and often openly hostile Pathan tribesmen in check. During this time the North-West Frontier was the scene of considerable political and civil unrest and the troops stationed at Razmak, Bannu and Wanna saw an extensive amount of action.[18]

During World War II (1939–45), there were ten Gurkha regiments, with two battalions each making a total of twenty pre-war battalions.[19] Following the evacuation of the BEF from Dunkirk in 1940, the Nepalese government offered to increase recruitment to increase the total number of Gurkha battalions in British service to thirty-five.[20] This would eventually rise to forty-five battalions and in order to achieve this, third and fourth battalions were raised for all ten regiments, with fifth battalions also being raised for 1 GR, 2 GR and 9 GR.[19] This expansion required ten training centres to be established for basic training and regimental records across India. In addition five training battalions[21] were raised, while other units[22] were raised as garrison battalions for keeping the peace in India and defending rear areas.[23] Large numbers of Gurkha men were also recruited for non-Gurkha units, and other specialised functions such as paratroops, signals, engineers, and military police.

A total of 250,280[23] Gurkhas served during the war, in almost all theatres. In addition to keeping peace in India, Gurkhas fought in Syria, North Africa, Italy, Greece and against the Japanese in the jungles of Burma, northeast India and also Singapore.[24] They did so with considerable distinction, earning 2,734 bravery awards in the process[23] and suffering around 32,000 casualties in all theatres.[25]

Gurkha military rank system in the British Indian Army

Gurkha ranks in the British Indian Army followed the same pattern as those used throughout the rest of the Indian Army at that time.[26] As in the British Army itself, there were three distinct levels: private soldiers, non-commissioned officers and commissioned officers. Commissioned officers within the Gurkha regiments held a Viceroy's Commission, which was distinct from the King's or Queen's Commission that British officers serving with a Gurkha regiment held. Any Gurkha holding a commission was technically subordinate to any British officer, regardless of rank.[27]

British Indian Army and current Indian Army ranks/current British Army equivalents

Viceroy Commissioned Officers (VCOs) up to 1947 and Junior Commissioned Officers (JCOs) from 1947

- Subedar Major/No equivalent

- Subedar/ No equivalent

- Jemadar (now Naib Subedar)/No equivalent

Warrant officers

- Regimental Havildar Major/Regimental Sergeant Major

- Company Havildar Major/Company Sergeant Major

Non-commissioned officers

- Company Quartermaster Havildar/Company Quartermaster Sergeant

- Havildar/Sergeant

- Naik/Corporal

- Lance Naik/Lance Corporal

Private soldiers

- Rifleman

(Source: Cross & Gurung 2002, pp. 33–34).

Notes

- British Army officers received Queen's or King's Commissions, but Gurkha officers in this system received the Viceroy's Commission. After Indian independence in 1947, Gurkha officers in regiments which became part of the British Army received the King's (later Queen's) Gurkha Commission, and were known as King's/Queen's Gurkha Officers (KGO/QGO). Gurkha officers had no authority to command troops of British regiments. The QGO Commission was abolished in 2007.

- Jemadars and subedars normally served as platoon commanders and company 2ICs, but were junior to all British officers, while the subedar major was the Commanding Officer's 'advisor' on the men and their welfare. For a long time it was impossible for Gurkhas to progress further, except that an honorary lieutenancy or captaincy was very rarely bestowed upon a Gurkha on retirement.[27]

- The equivalent ranks in the post-1947 Indian Army were (and are) known as Junior Commissioned Officers (JCOs). They retained the traditional rank titles used in the British Indian Army — Jemadar (later Naib Subedar), Subedar and Subedar Major.

- While in principle any British subject may apply for a commission without having served in the ranks, Gurkhas cannot. It was customary for a Gurkha soldier to rise through the ranks and prove his ability before his regiment would consider offering him a commission.[27]

- From the 1920s Gurkhas could also receive King's Indian Commissions, and later full King's or Queen's Commissions, which put them on a par with British officers. This was rare until after the Second World War.

- Gurkha officers commissioned from the Royal Military Academy - Sandhurst and Short Service Officers regularly fill appointments up to the rank of major. At least two Gurkhas have been promoted to lieutenant colonel and there is theoretically now no bar to further progression.[27]

- After 1948 the Brigade of Gurkhas (part of the British Army) was formed and adopted standard British Army rank structure and nomenclature, except for the three Viceroy Commission ranks between Warrant Officer 1 and Second Lieutenant—jemadar, subedar and subedar major—which remained, albeit with different rank titles Lieutenant (Queens Gurkha Officer), Captain (QGO) and Major (QGO). The QGO commission was abolished in 2007, Gurkha soldiers are currently commissioned as Late Entry Captains.(as above).[27]

Regiments of the Gurkha Rifles (c.1815–1947)

- 1st King George V's Own Gurkha Rifles (The Malaun Regiment) (raised 1815, allocated to Indian Army at independence in 1947)

- 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles (The Sirmoor Rifles) (raised 1815, allocated to British Army in 1948)

- 3rd Queen Alexandra's Own Gurkha Rifles (raised 1815, allocated to Indian Army at independence in 1947)

- 4th Prince of Wales's Own Gurkha Rifles (raised 1857, allocated to Indian Army at independence in 1947)

- 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles (Frontier Force) (raised 1858, allocated to Indian Army at independence in 1947)

- 6th Gurkha Rifles, renamed 6th Queen Elizabeth's Own Gurkha Rifles in 1959 (raised 1817, allocated to British Army in 1948)

- 7th Gurkha Rifles, renamed 7th Duke of Edinburgh's Own Gurkha Rifles in 1959 (raised 1902, allocated to British Army in 1948)

- 8th Gurkha Rifles (raised 1824, allocated to Indian Army at independence in 1947)

- 9th Gurkha Rifles (raised 1817, allocated to Indian Army at independence in 1947)

- 10th Princess Mary's Own Gurkha Rifles (raised 1890, allocated to British Army in 1948)

- 11th Gorkha Rifles (1918–1922; raised again by India following independence in 1947)

- 25th Gurkha Rifles (1942–1946)

- 26th Gurkha Rifles (1943–1946)

- 29th Gurkha Rifles (1943–1946)

- 42nd Gurkha Rifles (raised 1817 as the Cuttack Legion, renamed 6th Gurkha Rifles in 1903)

- 44th Gurkha Rifles (raised 1824 as the 16th (Sylhet) Local Battalion, renamed 8th Gorkha Rifles in 1903)

Second World War training battalions

- 14th Gurkha Rifles Training Battalion [28]

- 38th Gurkha Rifles Training Battalion [28]

- 56th Gurkha Rifles Training Battalion [28]

- 710th Gurkha Rifles Training Battalion [28]

Post-independence (1947–present)

SOLDIER

Bravest of the brave,

most generous of the generous,

never had country

more faithful friends

than you.

Professor Sir Ralph Turner MC[29]

After Indian independence—and partition—in 1947 and under the Tripartite Agreement, the original ten Gurkha regiments consisting of the twenty pre-war battalions were split between the British Army and the newly independent Indian Army.[23] Six Gurkha regiments (twelve battalions) were transferred to the post-independence Indian Army, while four regiments (eight battalions) were transferred to the British Army.[30]

To the disappointment of their British officers the majority of Gurkhas given a choice between British or Indian Army service opted for the latter. The reason appears to have been the pragmatic one that the Gurkha regiments of the Indian Army would continue to serve in their existing roles in familiar territory and under terms and conditions that were well established.[31] The only substantial change was the substitution of Indian officers for British. By contrast the four regiments selected for British service faced an uncertain future in (initially) Malaya—a region where relatively few Gurkhas had previously served. The four regiments (or eight battalions) in British service have since been reduced to a single (two battalion) regiment while the Indian units have been expanded beyond their pre-Independence establishment of twelve battalions.[32]

The principal aim of the Tripartite Agreement was to ensure that Gurkhas serving under the Crown would be paid on the same scale as those serving in the new Indian Army.[33] This was significantly lower than the standard British rates of pay. While the difference is made up through cost of living and location allowances during a Gurkha's actual period of service, the pension payable on his return to Nepal is much lower than would be the case for his British counterparts.[34]

With the abolition of the Nepalese monarchy, the future recruitment of Gurkhas for British and Indian service has been put into doubt. A spokesperson for the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), which is expected to play a major role in the new secular republic, has stated that recruitment as mercenaries is degrading to the Nepalese people and will be banned.[35]

British Army Gurkhas

- Main article Brigade of Gurkhas for details of British Gurkhas since 1948

Four Gurkha regiments joined the British Army on January 1, 1948:

- 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles (The Sirmoor Rifles)

- 6th Queen Elizabeth's Own Gurkha Rifles

- 7th Duke of Edinburgh's Own Gurkha Rifles

- 10th Princess Mary's Own Gurkha Rifles

They formed the Brigade of Gurkhas and were initially stationed in Malaya. There were also a number of additional Gurkha regiments including the 69th Gurkha Field Squadron and the 70th Gurkha Field Support Squadron, both of which were included in the 36th Engineer Regiment. Since then, British Gurkhas have served in Borneo during the Confrontation with Indonesia, in the Falklands conflict, and on various peacekeeping missions in Sierra Leone, East Timor, Bosnia and Kosovo.[36] They are currently serving in Afghanistan.

As of November 2006, the "Brigade of Gurkhas" in the British Army has the following units:

- 1st Battalion, The Royal Gurkha Rifles (1RGR)

- 2nd Battalion, The Royal Gurkha Rifles (2RGR)

- Queen's Gurkha Signals which includes:

- 250 Gurkha Signal Squadron

- 246 Gurkha Signal Squadron

- 248 Gurkha Signal Squadron

- Queen's Own Gurkha Logistics Regiment

- Queen's Gurkha Engineers which includes:

- 69th Gurkha Field Squadron

- 70th Gurkha Field Squadron

In addition to these Regiments, the Brigade of Gurkhas has its own clerks and chefs who are posted among the above mentioned units.

Gurkhas in Hong Kong:

- 26th Gurkha Brigade (1948–1950)

- 51st Infantry Brigade (disbanded 1976)

- 48th Gurkha Infantry Brigade (1957–1976; renamed Gurkha Field Force 1976–97; returned to old title 1987–ca.1992)

Indian Army Gorkhas

Upon independence in 1947, six of the original ten Gurkha regiments remained with the Indian Army.[30] These regiments were:

- 1 Gorkha Rifles

- 3 Gorkha Rifles

- 4 Gorkha Rifles

- 5 Gorkha Rifles

- 8 Gorkha Rifles

- 9 Gorkha Rifles

Additionally, a further regiment, 11 Gorkha Rifles, was raised. In 1949 the spelling was changed from "Gurkha" to "Gorkha".[37] All royal titles were dropped when India became a republic in 1950.[37]

Since partition, the Gurkha regiments that were transferred to the Indian Army have established themselves as a permanent and vital part of the newly independent Indian Army. Indeed, while Britain has reduced its Gurkha contingent, India has continued to recruit Gurkhas in large numbers.[32] Indeed, in 2009 the Indian Army had a Gurkha contingent that numbered around 42,000 men in forty-six battalions, spread across seven regiments.

Although their deployment is still governed by the 1947 Tripartite Agreement, in the post-1947 conflicts India has fought in, Gurkhas have served in almost all of them, including the wars with Pakistan in 1947, 1965 and 1971 and also against China in 1962.[38] They have also been used in peacekeeping operations around the world.[37] They have also served in Sri Lanka conducting operations against the Tamil Tigers.[39]

Nepalese Army Gurkhas

Two light infantry battalions of the Nepalese Army are also manned by Gurkhas;

- Shree Purano Gorakh Battalion—established 1763

- Shree Naya Gorakh Battalion—established 1783

These are the oldest Gurkha units in existence, and were utilised as palace guards by the King of Nepal, with one battalion always permanently deployed.[40] The Shree Purano Gorakh Battalion was the first major Nepalese contingent deployed on UN Peacekeeping operations, when it was deployed to the Sinai Peninsula in 1974.[41]

Singapore Gurkha Contingent

The Gurkha Contingent (GC) of the Singapore Police Force was formed on 9 April 1949 from selected ex-British Army Gurkhas. It is an integral part of the Police Force and was raised to replace a Sikh unit which had existed prior to the Japanese occupation during the Second World War.[42]

The GC is a well trained, dedicated and disciplined body whose principal role is as a specialist guard force. In times of crisis it can be deployed as a reaction force. During the turbulent years before and after independence, the GC acquitted itself well on a number of times during outbreaks of civil disorder. The Gurkhas displayed the courage, self restraint and professionalism for which they are famous and earned the respect of the society at large.[42]

Recently the GC can be seen patrolling the streets and have replaced local policemen to guard key installations. The most recent deployment of the GC was to provide additional security for the Singapore Airshow, Asia's largest airshow, and the hunt for the escaped terrorist, Mas Selamat.

Brunei Gurkha Reserve Unit

The Gurkha Reserve Unit is a special guard force in the Sultanate of Brunei. The 2,000 strong Gurkha unit is made up of British Army veterans.

Other

Ethnic identity

Ethnically, Gurkhas who are presently serving in the British armed forces are Indo-Tibeto-Mongolians. Gurkhas serving in the Indian Armed Forces are of both groups, Indo-Tibeto-Mongolian and ethnic Rajput. Gurkhas of Tibeto-Mongolian origin mostly belong to the Limbu, Gurung, Magar, Tamang, and Kiranti origin, many of whom are adherents of Tibetan Buddhism and Shamanism, under Hindu influence.[43]

All Gurkhas, regardless of ethnic origin, speak Nepali, also known as Khas Kura or Khas Bhasa, an Indo-Aryan language. They are also famous for their large knife called the khukuri, which is featured in an X shaped configuration on their emblem.

In the mid-1980s some Nepali speaking groups in West Bengal began to organize under the Gorkhaland National Liberation Front, calling for their own Gurkha state, Gorkhaland.

In the introduction to the book Gorkhas Imagined (2009) Prem Poddar makes an important point about the Gorkhas in Nepal versus the Gorkhas in India: "the word ‘Gorkha’ (or the neologism ‘Gorkhaness’) as a self-descriptive term ... has gained currency as a marker of difference for Nepalis living in India as opposed to their brethren and sistren in Nepal. Gorkhaliness then becomes synonymous with Indian Nepaleseness but invests only degrees of differential commonalities with Nepali Nepaliness and diasporic Nepaliness. While this counters the irredentism of a Greater Nepal thesis, it cannot completely exorcise the spectres or temptations of an ethnic absolutism for diasporic subjects."[44]

Victoria Cross recipients

There have been twenty-six Victoria Crosses awarded to members of the Gurkha regiments.[45] The first was awarded in 1858 and the last in 1965.[46] Thirteen of the recipients have been British officers serving with Gurkha regiments, although since 1915 the majority have been received by Gurkhas serving in the ranks as private soldiers or as NCOs.[11] In addition, since Indian independence in 1947, Gurkhas serving in the Indian Army have also been awarded three Param Vir Chakras, which are roughly equivalent.[47]

Of note also, there have been two George Cross medals awarded to Gurkha soldiers, for acts of bravery in situations that have not involved combat.[11]

Treatment of Gurkhas in the United Kingdom

The treatment of Gurkhas and their families was the subject of controversy in the United Kingdom once it became widely known that Gurkhas received smaller pensions than their British counterparts.[48] The nationality status of Gurkhas and their families was also an area of dispute, with claims that some ex-army Nepali families were being denied residency and forced to leave Britain. On 8 March 2007, the British Government announced that all Gurkhas who signed up after 1 July 1997 would receive a pension equivalent to that of their British counterparts. In addition, Gurkhas would, for the first time, be able to transfer to another army unit after five years' service and women would also be allowed to join - although not in first-line units - conforming to the British Army's policy. The act also guaranteed residency rights in Britain for retired Gurkhas and their families.

Despite the changes, many Gurkhas who had not served long enough to entitle them to a pension faced hardship on their return to Nepal, and some critics derided the Government's decision to only award the new pension and citizenship entitlement to those joining after 1 July 1997, claiming that this left many ex-Gurkha servicemen still facing a financially uncertain retirement. A pressure group, Gurkha Justice Campaign[49], and even the British National Party waded into the debate in support of the Gurkhas.[50]

In a landmark ruling on 30 September 2008 the High Court in London decided that Gurkhas who left the Army before 1997 did have an automatic right of residency in the United Kingdom.In line with the ruling of the High Court the Home Office is to review all cases affected by this decision.

On the 29 April 2009 a motion in the House of Commons by the Liberal Democrats that all Gurkhas be offered an equal right of residence resulted in a defeat for the Government by 267 votes to 246, the first, first day motion defeat for a government since 1978. Nick Clegg, the Liberal Democrat leader, stated that "This is an immense victory [...] for the rights of Gurkhas who have been waiting so long for justice, a victory for Parliament, a victory for decency." He added that it was "the kind of thing people want this country to do".[51]

On 21 May 2009, the Home Secretary Jacqui Smith announced that all Gurkha veterans who retired before 1997 with at least four years service would be allowed to settle in the UK. The actress and daughter of Gurkha corps major James Lumley, Joanna Lumley, who had highlighted the treatment of the Gurkhas and campaigned for their rights, commented: "This is the welcome we have always longed to give".[52]

A charity, the Gurkha Welfare Trust, provides aid to alleviate hardship and distress among Gurkha ex-servicemen.[53]

Hong Kong

A considerable number of ex-Gurkhas and their families live in Hong Kong, where they are particularly well represented in the private security profession (G4S Gurkha Services, Pacific Crown Security Service, Sunkoshi Gurkha Security) and among labourers. Ex-Gurkhas left barracks and moved into surrounding urban area. There are considerable Nepalese communities in Yuen Long and Kwun Chung.

British citizenship

A recent High Court decision on a test case in London has acknowledged the 'debt of honour' to Gurkhas discharged before 1997, and that immigration cases be reviewed, which could set a precedent for citizenship privileges.[54]

Malaysian Armed Forces and citizenship

After the Federation of Malaya became independent from the United Kingdom in August 1957, many Gurkhas became soldiers in the Malayan armed forces, especially in the Royal Ranger Regiment. Others became security guards, mainly in Kuala Lumpur.

The United States Navy employs Gurkha guards as sentries at its base in Naval Support Activity Bahrain and on the US Navy side of the pier at Mina Salaman. The Gurkhas work alongside Navy members in day-to-day operations.

Popular culture

- In the video game Dynasty General, Gurkha units can be recruited.

- In the video game Empire: Total War, the Gurkha unit appears as a special unit.

- In the video game Age of Empires III: The Asian Dynasties, Gurkhas appear as long-range riflemen available for the Indian civilization.

- In Michael Crichton's novel State of Fear the side hero is a Gurkha.

- In Karen Traviss's novel Gears of War: Aspho Fields the Pesang fictional people are heavily based on the Gurkha.

- In the Chris Bunch/Allan Cole The Sten Chronicles series of science fiction novels the Eternal Emperor has a battalion of Gurkha bodyguards recruited from Earth. The bodyguard disbands when the Emperor "dies" and re-enlists when he is "reborn".

- In the song "Funky Days" British band Cornershop mentions, "Before the Gurkhas get called up again…."

- In the Ultimate Force episode "Deadlier Than The Male" the leader of the hijackers, is Captain Allan Eastwood, formerly of the Ghurkas.

See also

- Bön

- History of Nepal

- Nepali language

- Trailwalker

Notes

- ↑ "Gurkhas form the major population group in Darjeeling district of West Bengal and Sikkim." Debnath, Monojit; Tapas K. Chaudhuri *Study of Genetic Relationships of Indian Gurkha Population on the basis of HLA - A and B Loci Antigens" International Journal of Human Genetics, 6(2): 159-162 (2006)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Chauhan 1996, pp. 28–30.

- ↑ Glossary of the tribes and castes of the Punjab and NWFP, H A Rose

- ↑ Kirat/Kirati people, Nepal History

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Tod & Crooke 1920.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Purushottam Sham Shere J B Rana 1998.

- ↑ Parker 2005, p. 58.

- ↑ Parker 2005, p. 57.

- ↑ Parker 2005, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Parker 2005, p. 79.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Parker 2005, p. xvii.

- ↑ Chappell 1993, p. 9.

- ↑ Parker 2005, p. 99.

- ↑ Sengupta 2007.

- ↑ Parker 2005, pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Parker 2005, p. 121.

- ↑ Parker 2005, p. 150.

- ↑ For more detail see Barthorp 2002.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Cross & Gurung 2002, p. 31.

- ↑ Parker 2005, pp. 157–158.

- ↑ 14 GR, 29 GR, 38 GR, 56 GR and 710 GR.

- ↑ 25 GR and 26 GR.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Cross & Gurung 2002, p. 32.

- ↑ "Participants from the Indian subcontinent in the Second World War". http://www.mgtrust.org/ind2.htm. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ↑ See Parker 2005, p. xvii. Gurkha casualties for the Second World War can be broken down as: 8,985 killed or missing and 23,655 wounded.

- ↑ Cross & Gurung 2002, p. 33.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 Cross & Gurung 2002, p. 34.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 "115 Infantry Brigade Subordanates". Order of Battle. http://www.ordersofbattle.com/UnitData.aspx?UniX=63267&Tab=Sub. Retrieved 2009-10-19.

- ↑ The inscription on a monument to Gurkha soldiers which was unveiled in 1997 in Whitehall, London (Staff.The Gurkhas — Britain's oldest allies BBC, 4 December 1997).

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Parker 2005, p. 224.

- ↑ Parker 2005, p. 226.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Parker 2005, p. 229.

- ↑ Parker 2005, pp. 322–323.

- ↑ Parker 2005, p. 323.

- ↑ Parker 2005, p. 344.

- ↑ Parker 2005, p. 360.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Chappell 1993, p. 12.

- ↑ Parker 2005, p. 230.

- ↑ Parker 2005, p. 203.

- ↑ Ayo Gorkhali! - History Lessons, 09/06/09

- ↑ Nepalese Army in UN PKOS - Nepalese Army

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Parker 2005, p. 390.

- ↑ Ember & Ember 2003.

- ↑ Gorkhas Imagined: I.B. Rai in Translation, Mukti Prakashan, 2009

- ↑ Parker 2005, pp. 391–393.

- ↑ For a detailed list of the recipients and their deeds, see the British Ministry of Defence website: http://www.army.mod.uk/gurkhas/7561.aspx

- ↑ "Param Vir Chakra". Pride of India.net. http://www.prideofindia.net/param.html. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ Parker 2005, p. 334.

- ↑ on line petition, and supportive merchandise Gurkha Justice Campaign website.

- ↑ Real Racism in action BNP website.

- ↑ Brown defeated over Gurkha rules http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/8023882.stm

- ↑ BBC News - Gurkhas win right to settle in UK http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/8060607.stm

- ↑ Parker 2005, pp. 379–383.

- ↑ See http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/7644441.stm.

References

- Barthorp, Michael. (2002).Afghan Wars and the North-West Frontier 1839-1947. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-36294-8

- Chappell, Mike (1993). The Gurkhas. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781855323575.

- Chauhan, Dr. Sumerendra Vir Singh. (1996). The Way of Sacrifice: The Rajputs, Pages 28–30, Graduate Thesis, South Asian Studies Department, Dr. Joseph T. O'Connell, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario Canada.

- Cross, J.P & Buddhiman Gurung. (2002) Gurkhas at War: Eyewitness Accounts from World War II to Iraq. Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-85367-727-4.

- Ember, Carol & Ember, Melvin. (2003). Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Men and Women in the World's Cultures. Springer. ISBN 030647770X.

- Parker, John. (2005). The Gurkhas: The Inside Story of the World's Most Feared Soldiers. Headline Book Publishing. ISBN 978-07553-1415-7

- Poddar, Prem and Anmole Prasad. (2009). Gorkhas Imagined: I.B. Rai in Transaltion. Mukti Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-909354-0-1

- Purushottam Sham Shere J B Rana. (1998). Jung Bahadur Rana-The Story of His Rise and Glory. ISBN 81-7303-087-1

- Sengupta, Kim. (2007). 'The Battle for Parity: Victory for the Gurkhas', The Independent, 9 March 2007. Retrieved from: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/this-britain/the-battle-for-parity-victory-for-the-gurkhas-439464.html

- Tod, James & Crooke, William. (eds.) (1920). Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan. 3 Volumes. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Pvt. Ltd., Delhi. Reprinted 1994.

Further reading

- Austin, Ian and Thakur Nahar Singh Jasol. (eds.) The Mewar Encyclopedia.

- Austin, Ian. (1999). Mewar—The World’s Longest Serving Dynasty. Roli Books, Delhi/The House of Mewar.

- Davenport, Hugh. (1975). The Trials and Triumphs of the Mewar Kingdom. Maharana Mewar Charitable Foundation, Udaipur.

- Farwell, Byron. (1985).The Gurkhas. W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-30714-X

- Goswami, C.G. and M.N. Mathur. Mewar and Udaipur. Himnashu Publications, Udaipur-New Delhi.

- Griffiths, Neil. Gurkha Walking books: 'Hebridean Gurkha; 'Gurkha Highlander'; 'Gurkha Reiver'. Neil takes a Scottish cross-country walk with Gurkhas every year to raise funds for the Gurkha Welfare Trust.

- Latimer, Jon. (2004). Burma: The Forgotten War, London: John Murray. ISBN 9780719565762.

- Pemble, John. (2009). Forgetting and remembering Britain's Gurkha War. Asian Affairs, 40(3), 361–376. Abstract available here (retrieved 12-22-2009). Contains a historiographical analysis of the Gurkha "legend."

- Tucci, Sandro. (1985). Gurkhas. Published by H.Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-11690-2.

- British Broadcasting Commission Staff (2007). "Gurkha tells of citizenship joy". BBC News, 2 June 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/6715743.stm. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

External links

- Gurkha Museum

- The Tripartite Agreement (TPA) 1947

- Twenty-Six Victoria Crosses have been won by Gurkha Regiments

Smoke Ghurka