Georgism

| Economics |

|

|

Economies by region

|

| General categories |

|---|

|

Microeconomics · Macroeconomics |

| Methods |

|

Mathematical (Game theory · Optimization) |

| Fields and subfields |

|

Behavioral · Cultural · Evolutionary |

| Lists |

|

Journals · Publications |

|

Economic ideologies

|

| Business and Economics Portal |

Georgism, named after Henry George (1839-1897), is a philosophy and economic ideology that holds that everyone owns what they create, but that everything found in nature, most importantly land, belongs equally to all of humanity. The Georgist philosophy is usually associated with the idea of a single tax on the value of land. Georgists argue that a tax on land value is efficient, fair and equitable, and will accrue sufficient revenue so that other taxes (which are less fair and efficient) can be reduced or eliminated.[1]

Contents |

Main tenets

Henry George is known best for his argument that the economic rent of land should be shared equally by the people of a society rather than being owned privately. The best statement of this opinion is found in his publication Progress and Poverty: "We must make land common property."[2] Although this could be done by nationalizing land and then leasing it to private parties, George preferred taxing unimproved land value, in part because this would be less disruptive and controversial in a country where land titles have already been granted to individuals. With the revenue from this "single tax", three possibilities arise: either the revenue can be used to fund the state or it can be redistributed to citizens as a pension or basic income, or it can be divided between the first two options. If the first option were to be chosen, the state could avoid having to tax any other type of income, wealth or transactions. Introducing a large land value tax causes the price of land titles to decrease correspondingly, but George did not believe landowners should be compensated, and described the issue as being analogous to compensation of former slave owners.

Georgists also argue that all of the economic rent (i.e., unearned income) collected from natural resources (land, mineral extraction, the broadcast spectrum, tradable emission permits, fishing quotas, airway corridor use, space orbits, etc.) and extraordinary returns from natural monopolies should accrue to the community rather than a private owner, and that no other taxes or burdensome economic regulations should be levied. In practice, the elimination of all other taxes implies a great land value tax, and a corresponding decrease of the price of possession of land. Adam Smith first argued that there would not be any change of land rental prices in his book The Wealth of Nations:[3]

Ground-rents are a still more proper subject of taxation than the rent of houses. A tax upon ground-rents would not raise the rents of houses. It would fall altogether upon the owner of the ground-rent, who acts always as a monopolist, and exacts the greatest rent which can be got for the use of his ground. More or less can be got for it according as the competitors happen to be richer or poorer, or can afford to gratify their fancy for a particular spot of ground at a greater or smaller expense.In every country the greatest number of rich competitors is in the capital, and it is there accordingly that the highest ground-rents are always to be found. As the wealth of those competitors would in no respect be increased by a tax upon ground-rents, they would not probably be disposed to pay more for the use of the ground. Whether the tax was to be advanced by the inhabitant, or by the owner of the ground, would be of little importance. The more the inhabitant was obliged to pay for the tax, the less he would incline to pay for the ground; so that the final payment of the tax would fall altogether upon the owner of the ground-rent.

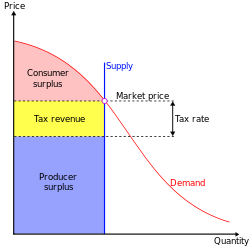

Standard economic theory suggests that a land value tax would be extremely efficient – unlike other taxes, it does not reduce economic productivity.[1] The 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize winner Milton Friedman, agreed that Henry George's land tax is potentially beneficial because unlike other taxes, land value tax does not depress economic activity by imposing an excess burden (or "deadweight loss") on the economy. A replacement of other more distortionary taxes with a land value tax would thus improve economic welfare.[4] Additionally, a land value tax would be a tax of wealth, and so would tend to reduce income inequality.

Modern environmentalists have agreed with the idea of the earth as the common property of humanity, and some have endorsed the idea of ecological tax reform as a replacement for command and control regulation. This would entail substantial taxes or fees for pollution, waste disposal and resource exploitation, or equivalently a "cap and trade" system where permits are auctioned to the highest bidder. This would also include taxes of the use of land and other natural resources.

Synonyms and variants

Most early advocacy groups described themselves as Single Taxers, and George endorsed this as being an accurate description of the philosophy's main political goal – the replacement of all taxes with a land value tax. During the modern era, some groups inspired by Henry George emphasize environmentalism more than other aspects, while others emphasize his ideas concerning economics.

Some devotees are not entirely satisfied with the name Georgist. Henry George is now little known and the idea of a single tax of land predates him. Some people now use the term "Geoism", with the meaning of "Geo" deliberately ambiguous. "Earth Sharing"[5] "Geoism",[6] "Geonomics" [7] and "Geolibertarianism"[8] (see libertarianism) are also preferred by some Georgists; "Geoanarchism" is another one.[9] These terms represent a difference of emphasis, and sometimes real differences about how land rent should be spent (citizen's dividend or just replacing other taxes); but all agree that land rent should be recovered from its private recipients.

Influence

Several communities were initiated with Georgist principles during the height of the philosophy's popularity. Two such communities that still exist are Arden, Delaware, which was founded during 1900 by Frank Stephens and Will Price, and Fairhope, Alabama, which was founded during 1894 by the auspices of the Fairhope Single Tax Corporation.

The German protectorate of Jiaozhou Bay (also known as Kiaochow) in China fully implemented Georgist policy. Its sole source of government revenue was the land value tax of six percent which it levied on its territory. The German government had previously had economic problems with its African colonies caused by land speculation. One of the main aims in using the land value tax in Jiaozhou Bay was to eliminate such speculation, an aim which was entirely achieved.[10] The colony existed as a German protectorate from 1898 until 1914 when it was seized by Japan. In 1922 it was returned to China.

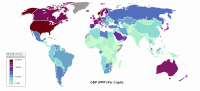

In the UK during 1909, the Liberal Government of the time included a land tax as part of several taxes in the People's Budget aimed at redistributing wealth (including a progressively graded income tax and an increase of inheritance tax). This caused a crisis which resulted indirectly in reform of the House of Lords. The budget was passed eventually - but without the land tax. George's ideas were also adopted to some degree in Australia, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, and Taiwan. In these countries, governments still levy some type of land value tax, albeit with exemptions.[11]

In Denmark, the Georgist Justice Party has previously been represented in Folketinget. It formed part of a centre-left government 1957-60 and was also represented in the European Parliament 1978-79.

In the 2004 Presidential campaign, Ralph Nader mentioned Henry George in his policy statements.[12] Also in the U.S., the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy is based on the ideas of Henry George[13] It should be noted that many municipal governments of the USA depend on real property tax as their main source of revenue, although such taxes are not "Georgian" since they generally include the value of buildings and other "improvements".

The periodical magazine Land&Liberty, established during 1894, is claimed by The American Journal of Economics and Sociology to be “the longest-lived Georgist project in history”.[14]

Criticism

Although both advocated for workers' rights, Henry George and Karl Marx were antagonists. Marx saw the Single Tax platform as a step backwards from the transition to communism. He argued that, "The whole thing is... simply an attempt, decked out with socialism, to save capitalist domination and indeed to establish it afresh on an even wider basis than its present one."[15] Marx also criticized the way land value tax theory emphasizes the value of land, arguing that, "His fundamental dogma is that everything would be all right if ground rent were paid to the state."[15]

On his part, Henry George predicted that if Marx's ideas were tried the likely result would be a dictatorship.[16] Fred Harrison provides a full treatment of Marxist objections to land value taxation and Henry George in "Gronlund and other Marxists - Part III: nineteenth-century Americas critics", American Journal of Economics and Sociology, (Nov 2003).[17]

More recent critics have claimed that increasing government spending has rendered a land tax insufficient to fund government, although the tax revenues would probably have been adequate for limited governments of the type that dominated during the period in which George was active. Also, George has been accused of exaggerating the importance of his "all-devouring rent thesis" in claiming that it is the primary cause of poverty and injustice in society.[18]

Famous people influenced by Georgism

|

|

|

Elizabeth "Lizzie" J. Phillips http://timelines.com/1904/1/5/lizzie-magie-is-granted-us-patent-for-the-landlords-game

See also

- Tragedy of the anticommons

- Mutualism

- Geolibertarianism

- Excess burden of taxation

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Land Value Taxation: An Applied Analysis, William J. McCluskey, Riël C. D. Franzsen

- ↑ George, Henry (1879). "2". Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth. VI. http://www.econlib.org/library/YPDBooks/George/grgPP26.html. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ↑ The Wealth of Nations Book V, Chapter 2, Article I: Taxes upon the Rent of Houses.

- ↑ Foldvary, Fred E. "Geo-Rent: A Plea to Public Economists". Econ Journal Watch (April 2005)[1]

- ↑ Introduction to Earth Sharing,

- ↑ Socialism, Capitalism, and Geoism - by Lindy Davies

- ↑ Geonomics in a Nutshell

- ↑ Geoism and Libertarianism by Fred Foldvary

- ↑ Geoanarchism: A short summary of geoism and its relation to libertarianism - by Fred Foldvary

- ↑ Silagi, Michael and Faulkner, Susan N., , Land Reform in Kiaochow, China: From 1898 to 1914 the Menace of Disastrous Land Speculation was Averted by Taxation, American Journal of Economics and Sociology, volume 43, Issue 2, pages 167-177

- ↑ Gaffney, M. Mason. "Henry George 100 Years Later". Association for Georgist Studies Board. http://www.georgiststudies.org/george100years.html. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20040828085138/http://www.votenader.org/issues/index.php?cid=7

- ↑ http://www.lincolninst.edu/aboutlincoln/

- ↑ The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 62, 2003, p. 615

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Karl Marx - Letter to Friedrich Adolph Sorge in Hoboken

- ↑ Henry George's Thought [1878822810] - $49.95 : Zen Cart!, The Art of E-commerce

- ↑ 14 Gronlund and other Marxists - Part III: nineteenth-century Americas critics | American Journal of Economics and Sociology, The | Find Articles at BNET

- ↑ Critics of Henry George

- ↑ Muse return with new album The Resistance "Sure, he has already launched into a passionate soliloquy about Geoism (the land-tax movement inspired by the 19th-century political economist Henry George)".

- ↑ Carlson, Allan. The New Agrarian Mind: The Movement Toward Decentralist Thought in Twentieth-Century America Transaction Publishers, 2004 (pg 51).

- ↑ http://www.wealthandwant.com/docs/Buckley_HG.html William F. Buckley, Jr. Transcript of an interview with Brian Lamb, CSpan Book Notes, April 2-3, 2000

- ↑ Transcript of a speech by Darrow on taxation

- ↑ Lane, Fintan. The Origins of Modern Irish Socialism, 1881-1896.Cork University Press, 1997 (pgs.79,81).

- ↑ Transcript of 1942 interview with Henry Ford in which he says, "The time will come when not an inch of the soil, not a single crop, not even weeds, will be wasted. Then every American family can have a piece of land. We ought to tax all idle land the way Henry George said — tax it heavily, so that its owners would have to make it productive".

- ↑ People's Budget

- ↑ The Life of Henry George, Part 3 Chapter X1

- ↑ Co-founder of the Henry George Club, Australia.

- ↑ Arcas Cubero, Fernando: El movimiento georgista y los orígenes del Andalucismo : análisis del periódico "El impuesto único" (1911-1923). Málaga : Editorial Confederación Española de Cajas de Ahorros, 1980. ISBN 8450037840

- ↑ Justice for Mumia Abu-Jamal

- ↑ Andelson Robert V. (2000), Land-Value Taxation Around the World: Studies in Economic Reform and Social Justice Malden, MA:Blackwell Publishers, Inc. Page 359.

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20040828085138/http://www.votenader.org/issues/index.php?cid=7

- ↑ .Article on Tolstoy, Proudhon and George. Count Tolstoy once said of George, "People do not argue with the teaching of George, they simply do not know it".

- ↑ "Oregon Biographies: William S. U'Ren". Oregon History Project. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society. 2002. http://www.ohs.org/education/oregonhistory/Oregon-Biographies-William-Uren.cfm. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

- ↑ Bill Vickrey - In Memoriam

External links

- Center for the Study of Economics

- Henry George Biography

- Henry George Foundation of America

- The Henry George Institute

- Henry George Papers, New York Public Library

- The Henry George School, founded 1932

- Prosper Australia (formerly the Henry George League)

- Robert Schalkenbach Foundation

- Understanding Economics

- Georgist Education Association

|

|||||||||||||||||