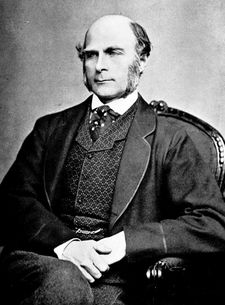

Francis Galton

| Francis Galton | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 16 February 1822 Birmingham, England |

| Died | 17 January 1911 (aged 88) Haslemere, Surrey, England |

| Residence | England |

| Nationality | English |

| Fields | Anthropology and polymathy |

| Institutions | Meteorological Council Royal Geographical Society |

| Alma mater | King's College London Cambridge University |

| Doctoral advisor | William Hopkins |

| Doctoral students | Karl Pearson |

| Known for | Eugenics The Galton board Regression toward the mean Standard deviation Weather map |

| Notable awards | Linnean Society of London's Darwin–Wallace Medal in 1908. Copley medal (1910) |

Sir Francis Galton FRS (16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911), cousin of Sir Douglas Galton, half-cousin of Charles Darwin, was an English Victorian polymath, anthropologist, eugenicist, tropical explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist, proto-geneticist, psychometrician, and statistician. He was knighted in 1909.

Galton had a prolific intellect, and produced over 340 papers and books throughout his lifetime. He also created the statistical concept of correlation and widely promoted regression toward the mean. He was the first to apply statistical methods to the study of human differences and inheritance of intelligence, and introduced the use of questionnaires and surveys for collecting data on human communities, which he needed for genealogical and biographical works and for his anthropometric studies.

He was a pioneer in eugenics, coining the very term itself and the phrase "nature versus nurture". His book, Hereditary Genius (1869), was the first social scientific attempt to study genius and greatness.[1] As an investigator of the human mind, he founded psychometrics (the science of measuring mental faculties) and differential psychology. He devised a method for classifying fingerprints that proved useful in forensic science.

As the initiator of scientific meteorology, he devised the first weather map, proposed a theory of anticyclones, and was the first to establish a complete record of short-term climatic phenomena on a European scale.[2] He also invented the Galton Whistle for testing differential hearing ability.

Contents |

Biography

Early life

He was born at "The Larches", a large house in the Sparkbrook area of Birmingham, England, built on the site of "Fair Hill", the former home of Joseph Priestley, which the botanist William Withering had renamed. He was Charles Darwin's half-cousin, sharing the common grandparent Erasmus Darwin. His father was Samuel Tertius Galton, son of Samuel "John" Galton. The Galtons were famous and highly successful Quaker gun-manufacturers and bankers, while the Darwins were distinguished in medicine and science.

Both families boasted Fellows of the Royal Society and members who loved to invent in their spare time. Both Erasmus Darwin and Samuel Galton were founder members of the famous Lunar Society of Birmingham, whose members included Boulton, Watt, Wedgwood, Priestley, Edgeworth, and other distinguished scientists and industrialists. Likewise, both families boasted literary talent, with Erasmus Darwin notorious for composing lengthy technical treatises in verse, and Aunt Mary Anne Galton known for her writing on aesthetics and religion, and her notable autobiography detailing the unique environment of her childhood populated by Lunar Society members.

Galton was by many accounts a child prodigy — he was reading by the age of 2, at age 5 he knew some Greek, Latin and long division, and by the age of six he had moved on to adult books, including Shakespeare for pleasure, and poetry, which he quoted at length (Bulmer 2003, p. 4). Later in life, Galton would propose a connection between genius and insanity based on his own experience. He stated, “Men who leave their mark on the world are very often those who, being gifted and full of nervous power, are at the same time haunted and driven by a dominant idea, and are therefore within a measurable distance of insanity” [3]

He attended King Edward's School, Birmingham, but chafed at the narrow classical curriculum, and left at 16.[4] His parents pressed him to enter the medical profession, and he studied for two years at Birmingham General Hospital and King's College, London Medical School. He followed this up with mathematical studies at Trinity College, University of Cambridge, from 1840 to early 1844.[5]

A severe nervous breakdown altered his original intention to try for honours. He elected instead to take a "poll" (pass) B.A. degree, like his half-cousin Charles Darwin (Bulmer 2003, p. 5). (Following the Cambridge custom, he was awarded an M.A. without further study, in 1847). He then briefly resumed his medical studies. The death of his father in 1844 left him financially independent but emotionally destitute, and he terminated his medical studies entirely, turning to foreign travel, sport and technical invention.

In his early years Galton was an enthusiastic traveller, and made a notable solo trip through Eastern Europe to Constantinople, before going up to Cambridge. In 1845 and 1846 he went to Egypt and travelled down the Nile to Khartoum in the Sudan, and from there to Beirut, Damascus and down the Jordan. In 1850 he joined the Royal Geographical Society, and over the next two years mounted a long and difficult expedition into then little-known South West Africa (now Namibia).

He wrote a successful book on his experience, "Narrative of an Explorer in Tropical South Africa". He was awarded the Royal Geographical Society's gold medal in 1853 and the Silver Medal of the French Geographical Society for his pioneering cartographic survey of the region (Bulmer 2003, p. 16). This established his reputation as a geographer and explorer. He proceeded to write the best-selling The Art of Travel, a handbook of practical advice for the Victorian on the move, which went through many editions and still reappears in print today.

In January 1853 he met Louisa Jane Butler (1822-1897) at his neighbour's home and they were married on 1 August 1853. The union of 43 years which followed was to prove a childless one. [6][7]

Middle years

Galton was a polymath who made important contributions in many fields of science, including meteorology (the anti-cyclone and the first popular weather maps), statistics (regression and correlation), psychology (synaesthesia), biology (the nature and mechanism of heredity), and criminology (fingerprints). Much of this was influenced by his penchant for counting or measuring. Galton prepared the first weather map published in The Times (1 April 1875, showing the weather from the previous day, 31 March), now a standard feature in newspapers worldwide.[8]

He became very active in the British Association for the Advancement of Science, presenting many papers on a wide variety of topics at its meetings from 1858 to 1899 (Bulmer 2010, p. 29). He was the general secretary from 1863 to 1867, president of the Geographical section in 1867 and 1872, and president of the Anthropological Section in 1877 and 1885. He was active on the council of the Royal Geographical Society for over forty years, in various committees of the Royal Society, and on the Meteorological Council.

During this time, Galton wrote a controversial letter to the Times titled 'Africa for the Chinese', where he argued that the Chinese, as a race capable of high civilization and (in his opinion) only temporarily stunted by the recent failures of Chinese dynasties, should be encouraged to immigrate to Africa and displace the supposedly inferior aboriginal blacks.[9]

Heredity, historiometry and eugenics

The publication by his cousin Charles Darwin of The Origin of Species in 1859 was an event that changed Galton's life. He came to be gripped by the work, especially the first chapter on "Variation under Domestication" concerning the breeding of domestic animals. An interesting fact, not widely known, is that Galton was present to hear the famous 1860 Oxford evolution debate at the British Association. The evidence for this comes from his wife Louisa's Annual Record for 1860.[10]

Galton devoted much of the rest of his life to exploring variation in human populations and its implications, at which Darwin had only hinted. In doing so, he eventually established a research programme which embraced many aspects of human variation, from mental characteristics to height, from facial images to fingerprint patterns. This required inventing novel measures of traits, devising large-scale collection of data using those measures, and in the end, the discovery of new statistical techniques for describing and understanding the data.

Galton was interested at first in the question of whether human ability was hereditary, and proposed to count the number of the relatives of various degrees of eminent men. If the qualities were hereditary, he reasoned, there should be more eminent men among the relatives than among the general population. He obtained his data from various biographical sources and compared the results that he tabulated in various ways. This pioneering work was described in detail in his book [11] in 1869. He showed, among other things, that the numbers of eminent relatives dropped off when going from the first degree to the second degree relatives, and from the second degree to the third. He took this as evidence of the inheritance of abilities. He also proposed adoption studies, including trans-racial adoption studies, to separate out the effects of heredity and environment.

The method used in Hereditary Genius has been described as the first example of historiometry. To bolster these results, and to attempt to make a distinction between 'nature' and 'nurture' (he was the first to apply this phrase to the topic), he devised a questionnaire that he sent out to 190 Fellows of the Royal Society. He tabulated characteristics of their families, such as birth order and the occupation and race of their parents. He attempted to discover whether their interest in science was 'innate' or due to the encouragements of others. The studies were published as a book, English men of science: their nature and nurture, in 1874. In the end, it promoted the nature versus nurture question, though it did not settle it, and provided some fascinating data on the sociology of scientists of the time.

Galton recognized the limitations of his methods in these two works, and believed the question could be better studied by comparisons of twins. His method was to see if twins who were similar at birth diverged in dissimilar environments, and whether twins dissimilar at birth converged when reared in similar environments. He again used the method of questionnaires to gather various sorts of data, which were tabulated and described in a paper The history of twins in 1875. In so doing he anticipated the modern field of behavior genetics, which relies heavily on twin studies. He concluded that the evidence favored nature rather than nurture.

Galton invented the term eugenics in 1883 and set down many of his observations and conclusions in a book, Inquiries into human faculty and its development.[12] He believed that a scheme of 'marks' for family merit should be defined, and early marriage between families of high rank be encouraged by provision of monetary incentives. He pointed out some of the tendencies in British society, such as the late marriages of eminent people, and the paucity of their children, which he thought were dysgenic. He advocated encouraging eugenic marriages by supplying able couples with incentives to have children.

Galton's study of human abilities ultimately led to the foundation of differential psychology and the formulation of the first mental tests.

Galton also devised a technique called composite photography, described in detail in Inquiries in human faculty and its development, which he believed could be used to identify types by appearance. He hoped his technique would aid medical diagnosis, and even criminology through the identification of typical criminal faces. However, he was forced to conclude after exhaustive experimentation that such types were not attainable in practice.

Joseph Jacobs

In the 1880s while the Jewish scholar Joseph Jacobs studied anthropology and statistics with Francis Galton, he asked Galton to create a composite of a Jewish type.[13]

Pangenesis experiments on rabbits

Galton conducted wide-ranging inquiries into heredity which led him to challenge Charles Darwin's hypothetical theory of pangenesis. Darwin had proposed as part of this hypothesis that certain particles, which he called "gemmules" moved throughout the body and were also responsible for the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Galton, in consultation with Darwin, set out to see if they were transported in the blood. In a long series of experiments in 1869 to 1871, he transfused the blood between dissimilar breeds of rabbits, and examined the features of their offspring.[14] He found no evidence of characters transmitted in the transfused blood (Bulmer 2003, pp. 116–118).

Darwin challenged the validity of Galton's experiment, giving his reasons in an article published in Nature where he wrote:

"Now, in the chapter on Pangenesis in my Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication I have not said one word about the blood, or about any fluid proper to any circulating system. It is, indeed, obvious that the presence of gemmules in the blood can form no necessary part of my hypothesis; for I refer in illustration of it to the lowest animals, such as the Protozoa, which do not possess blood or any vessels; and I refer to plants in which the fluid, when present in the vessels, cannot be considered as true blood." He goes on to admit: "Nevertheless, when I first heard of Mr. Galton's experiments, I did not sufficiently reflect on the subject, and saw not the difficulty of believing in the presence of gemmules in the blood."[15]

Galton explicitly rejected the idea of the inheritance of acquired characteristics (Lamarckism), and was an early proponent of "hard heredity" through selection alone. He came close to rediscovering Mendel's particulate theory of inheritance, but was prevented from making the final breakthrough in this regard because of his focus on continuous, rather than discrete, traits (now known as polygenic traits). He went on to found the Biometric approach to the study of heredity, distinguished by its use of statistical techniques to study continuous traits and population-scale aspects of heredity.

This approach was later taken up enthusiastically by Karl Pearson and W.F.R. Weldon; together, they founded the highly influential journal Biometrika in 1901. (R.A. Fisher would later show how the biometrical approach could be reconciled with the Mendelian approach.) The statistical techniques that Galton invented (correlation, regression — see below) and phenomena he established (regression to the mean) formed the basis of the biometric approach and are now essential tools in all the social sciences.

Statistics, standard deviation, regression and correlation

His inquiries into the mind involved detailed recording of subjects' own explanations for whether and how their minds dealt with things such as mental imagery, which he elicited by his pioneering use of the questionnaire. In the late 1860s, Galton conceived the standard deviation.[16]

Galton invented the use of the regression line (Bulmer 2003, p. 184), and was the first to describe and explain the common phenomenon of regression toward the mean, which he first observed in his experiments on the size of the seeds of successive generations of sweet peas. In the 1870s and 1880s he was a pioneer in the use of normal distribution to fit histograms of actual tabulated data. He invented the Quincunx, a pachinko-like device, also known as the bean machine, as a tool for demonstrating the law of error and the normal distribution (Bulmer 2003, p. 4). He also discovered the properties of the bivariate normal distribution and its relationship to regression analysis.

In 1906 Galton visited a livestock fair and stumbled upon an intriguing contest. An ox was on display, and the villagers were invited to guess the animal's weight after it was slaughtered and dressed. Nearly 800 gave it a go and, not surprisingly, not one hit the exact mark: 1,198 pounds. Astonishingly, however, the mean of those 800 guesses came close — very close indeed. It was 1,197 pounds.[17][18]

After examining forearm and height measurements, Galton introduced the concept of correlation in 1888 (Bulmer 2003, pp. 191–196). Correlation is the term used by Aristotle in his studies of animal classification, and later and most notably by Cuvier in Histoire des Progres des Sciences naturelles depuis (1789). Correlation originated in the study of correspondence as described in the study of morphology. See R.S. Russell, Form and Function. Galton's later statistical study of the probability of extinction of surnames led to the concept of Galton–Watson stochastic processes (Bulmer 2003, pp. 182–184).

He also developed early theories of ranges of sound and hearing, and collected large quantities of anthropometric data from the public through his popular and long-running Anthropometric Laboratory. It was not until 1985 that these data were analyzed in their entirety.

Fingerprints

In a Royal Institution paper in 1888 and three books (Fingerprints-1892, Decipherment of Blurred Finger Prints-1893, and Fingerprint Directories-1895)[19] Galton estimated the probability of two persons having the same fingerprint and studied the heritability and racial differences in fingerprints. He wrote about the technique (inadvertently sparking a controversy between Herschel and Faulds that was to last until 1917), identifying common pattern in fingerprints and devising a classification system that survives to this day.

The method of identifying criminals by their fingerprints had been introduced in the 1860s by Sir William James Herschel in India, and their potential use in forensic work was first proposed by Dr Henry Faulds in 1880, but Galton was the first to place the study on a scientific footing, which assisted its acceptance by the courts (Bulmer 2003, p. 35). Galton pointed out that there were specific types of fingerprint patterns. He described and classified them into eight broad categories. 1: plain arch, 2: tented arch, 3: simple loop, 4: central pocket loop, 5: double loop, 6: lateral pocket loop, 7: plain whorl, and 8: accidental.[20]

Final years

In an effort to reach a wider audience, Galton worked on a novel entitled Kantsaywhere from May until December 1910. The novel described a utopia organized by a eugenic religion, designed to breed fitter and smarter humans. His unpublished notebooks show that this was an expansion of material he had been composing since at least 1901. He offered it to Methuen for publication, but they showed little enthusiasm. Galton wrote to his niece that it should be either “smothered or superseded”. His niece appears to have burnt most of the novel, offended by the love scenes, but large fragments survive.[21]

Honours and impact

Over the course of his career Galton received many major awards, including the Copley medal of the Royal Society (1910). He received in 1853 the highest award from the Royal Geographical Society, one of two gold medals awarded that year, for his explorations and map-making of southwest Africa. He was elected a member of the prestigious Athenaeum Club in 1855 and made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1860. His autobiography also lists the following:[22]

- Silver Medal, French Geographical Society (1854)

- Gold Medal of the Royal Society (1886)

- Officier de l'Instruction Publique, France (1891)

- D.C.L. Oxford (1894)

- Sc.D. (Honorary), Cambridge (1895)

- Huxley Medal, Anthropological Institute (1901)

- Elected Hon. Fellow Trinity College, Cambridge (1902)

- Darwin Medal, Royal Society (1902)

- Linnean Society of London's Darwin–Wallace Medal (1908)

Galton was knighted in 1909. His statistical heir Karl Pearson, first holder of the Galton Chair of Eugenics at University College London, wrote a three-volume biography of Galton, in four parts, after his death (Pearson 1914, 1924, 1930). The eminent psychometrician Lewis Terman estimated that his childhood I.Q. was on the order of 200, based on the fact that he consistently performed mentally at roughly twice his chronological age (Forrest 1974). (This follows the original definition of IQ as mental age divided by chronological age, rather than the modern distribution-deviate definition.)

The flowering plant genus Galtonia was named in his honour.

See also

- A Large Attendance In The Antechamber, a play about Galton

- Darwin — Wedgwood family Darwin, Wedgwood and Galton's family tree

- Efficacy of prayer

- Historiometry

Notes

- ↑ Galton, F. 1869. Hereditary Genius. London: Macmillan.

- ↑ Francis Galton (1822–1911) – from Eric Weisstein's World of Scientific Biography

- ↑ Pearson, K. (1914). The life, letters and labours of Francis Galton (4 vols.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography accessed 31 Jan 2010

- ↑ Galton, Francis in Venn, J. & J. A., Alumni Cantabrigienses, Cambridge University Press, 10 vols, 1922–1958.

- ↑ http://galton.org/cgi-bin/searchImages/search/pearson/vol2/pages/vol2_0320.htm

- ↑ http://www.stanford.edu/group/auden/cgi-bin/auden/individual.php?pid=I7570&ged=auden-bicknell.ged

- ↑ http://www.galton.org/meteorologist.html

- ↑ http://galton.org/letters/africa-for-chinese/AfricaForTheChinese.htm

- ↑ Forrest DW 1974. Francis Galton: the life and work of a Victorian genius. Elek, London. p84

- ↑ Hereditary Genius

- ↑ Inquiries into human faculty and its development by Francis Galton

- ↑ Daniel Akiva Novak. Realism, photography, and nineteenth-century Cambridge University Press, 2008 ISBN 0-521-88525-6

- ↑ Science Show — 25/11/00: Sir Francis Galton

- ↑ http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=F1751&viewtype=side&pageseq=1

- ↑ Sir Francis Galton discovered the standard deviation

- ↑ http://adamsmithlives.blogs.com/thoughts/2007/10/experts-and-inf.html

- ↑ Schell, Barbara A Boyt (2007). Clinical And Professional Reasoning In Occupational Therapy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 372. ISBN 0781759145.

- ↑ Conklin, Barbara Gardner., Robert Gardner, and Dennis Shortelle. Encyclopedia of Forensic Science: a Compendium of Detective Fact and Fiction. Westport, Conn.: Oryx, 2002. Print.

- ↑ Innes, Brian (2005). Body in Question: Exploring the Cutting Edge in Forensic Science. New York: Amber Books. pp. 32–33. ISBN 1904687423.

- ↑ Life of Francis Galton by Karl Pearson Vol 3a : image 470

- ↑ Galton, Francis (1909). Memories of My Life:. New York: E. P. Dutton and Company. http://books.google.com/?id=MvAIAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA331&dq=Galton+awards+and+Degrees.

Further reading

- Bulmer, Michael (2003). Francis Galton: Pioneer of Heredity and Biometry. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7403-3

- Ewen, Stuart and Elizabeth Ewen (2006; 2008) "Nordic Nightmares," pp. 257–325 in Typecasting: On the Arts and Sciences of Human Inequality, Seven Stories Press. ISBN 978-1-58322-735-0

- Forrest, D.W (1974). Francis Galton: The Life and Work of a Victorian Genius. Taplinger. ISBN 0-8008-2682-5

- Galton, Francis (1909). Memories of My Life:. New York: E. P. Dutton and Company. http://books.google.com/?id=MvAIAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA3&dq=Samuel+%22John%22+Galton.

- Gillham, Nicholas Wright (2001). A Life of Sir Francis Galton: From African Exploration to the Birth of Eugenics, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514365-5

- Pearson, Karl (1914, 1924, 1930). "The life, letters and labours of Francis Galton (3 vols.)". http://galton.org

- Daniëlle Posthuma, Eco J. C. De Geus, Wim F. C. Baaré, Hilleke E. Hulshoff Pol, René S. Kahn & Dorret I. Boomsma (2002). "The association between brain volume and intelligence is of genetic origin". Nature Neuroscience 5 (2): 83–84. doi:10.1038/nn0202-83. PMID 11818967

- Quinche, Nicolas, Crime, Science et Identité. Anthologie des textes fondateurs de la criminalistique européenne (1860–1930). Genève: Slatkine, 2006, 368p., passim.

- doi:10.1111/j.1467-985X.2010.00643.x

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand

External links

- Francis Galton at Find a Grave

- Galton's Complete Works at Galton.org (including all his published books, all his published scientific papers, and popular periodical and newspaper writing, as well as other previously unpublished work and biographical material).

- Works by Francis Galton at Project Gutenberg

- The Galton Machine or Board demonstrating the normal distribution.

- Portraits of Galton from the National Portrait Gallery (United Kingdom)

- The Galton laboratory homepage (originally The Francis Galton Laboratory of National Eugenics) at University College London

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Francis Galton", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Gillham.html.

- Biography and bibliography in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

- History and Mathematics

- Human Memory — University of Amsterdam website with test based on the work of Galton

|

||||||||