Fustanella

Fustanella (for spelling in various languages, see chart below) is a traditional skirt-like garment worn by men of many nations in the Balkans, similar to the kilt. In modern times, the fustanella is part of traditional Albanian, Greek and Macedonian dresses, worn mainly by ceremonial Greek military units (such as the Evzones) and Albanian, Greek and Macedonian folk dancers. The dress was also worn by the Royal Guard of Albania (1924–1939).

Contents |

History

The fustanella is derived from a series of ancient garments such as the chiton (or tunic) and the chitonium (or short military tunic).[1] The Roman toga may have also influenced the evolution of the fustanella based on statues of Roman emperors wearing knee-length pleated kilts (in colder regions, more folds were added to provide greater warmth).[2]

Byzantine Greeks called the fustanella, or pleated kilt, podea. The wearer of the podea was either associated with a typical hero or an Akritic warrior and can be found in 12th century finds attributed to Manuel I Komnenos.[3] During the Ottoman period, the fustanella was worn by the armatoloi and the klephts.[4] The fustanella was originally thought to have been a southern Albanian outfit of the Tosks and introduced in Greece during the Ottoman occupation that began after the 15th century.[5][6]

Evolution

Albanian version

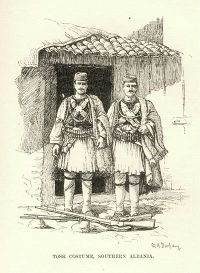

The Albanian fustanella appears for the first time in a document of 1335, which regards a sailor in the port of Drin river in the Skadar Lake, to whom were confiscated, among other things, the following items: his tunic, mantle, and his fustanum.[7] The Albanian version has around sixty pleats, or usually a moderate number.[8] It is made of heavy home-woven linen cloth.[8] The Albanian version has historically been of a skirt which was long enough to cover the whole thigh (knee included), leaving only the lower leg exposed.[8] It was usually worn by rich Albanians who would also expose an ornamented yataghan on the side and a pair of pistols with long chiseled silver-handles in the belt.[8]

The general custom in Albania was to dip the white kilts in hot melted sheep-fat for the double purpose of making them waterproof and less visible at a distance.[9] Usually, this was done by the men-at-arms (called in Albanian trima).[9] After being removed from the cauldron, the kilts were hung up to dry and then pressed with cold irons so as to create the pleats.[9] They had then a dull gray appearance but were not dirty by any means.[9]

The jacket, worn with the fustanella in the Albanian costume, has a free armhole to allow for the passage of the arm, while the sleeves, attached only on the upper part of the shoulders, are thrown back.[8] The sleeves can be worn, but usually aren't.[8] The footwear is of three types: the kundra, which are black shoes with a metal buckle; the sholla, which are sandals with leather thongs tied around a few inches above the ankle; and finally, the opinga, which is a soft leather shoe, with turned-up points, which, when intended for children, are surmounted with a pompon of black or red wool.[8]

Greek version

The number of pleats in the Greek version is much higher than the Albanian one. Some Greeks, such as General Theodoros Kolokotronis had almost four hundred pleats in their garments, one for each year of Turkish rule over Greece. The style evolved over time. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, the skirts hung below the knees, following the Albanian tradition, and the hem of the garment was gathered together with garters and tucked into the boots to create a "bloused" effect. Later, during the Bavarian regency, the skirts were shortened to create a sort of billowy pantaloon that stopped above the knee; this garment was worn with hose, and either buskins or decorative clogs. This is the costume worn by the modern Greek Evzones, the Presidential Guard.

While the image of warriors with frilly skirts tucked into their boots may seem impractical to a contemporary audience, modern paratroopers use a similar method to blouse their trousers over their jumpboots. Lace was commonly worn on military uniforms in the west until well into the 19th century, and gold braid and other adornments still serve as markers of high rank in formal military uniforms. Fustanella were very labor-intensive and thus costly, which made them a status garment that advertised the wealth and importance of the wearer. Western observers of the Greek War of Independence noted the great pride which the klephts and armatoloi took in their foustanella, and how they competed to outdo each other in the sumptuousness of their costume.

Name

The word derives from Italian fustagno 'fustian' + -ella (diminutive), the fabric from which the earliest kilts were made. This in turn derives from Medieval Latin fūstāneum, perhaps a diminutive form of fustis, "wooden baton". Other authors consider this a calque of Greek xylino lit. 'wooden' i.e. 'cotton'[10]; others speculate that it is derived from Fostat, a suburb of Cairo where cloth was manufactured.[11] The Greek plural is foustanelles (φουστανέλλες) but as with the (semi-correct) foustanellas, it is rarely employed by native English speakers.

Name in various languages

Native terms for "skirt" and "dress" included for comparison:

| Language | Kilt/short skirt | Skirt | Dress |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albanian | fustanellë/fustanella | fund | fustan |

| Aromanian | fustanelã | fustã | fustanã |

| Bulgarian | фустанела (fustanela) |

фуста (fusta) |

|

| Greek | φουστανέλλα (foustanélla) |

φούστα (foústa) |

φουστάνι (foustáni) |

| Italian | fustanella | gonna | |

| Macedonian | фустанела (fustanela) |

фустан (fustan) |

|

| Megleno-Romanian | fustan | fustan | |

| Romanian | rochiţă | fustă | rochie |

| Turkish | fistan |

Gallery

Sarakatsani Greeks in Thrace, 1938. |

Spiridon Louis, Olympic marathon champion (1896). |

Greek from Ioannina by Dupré Louis (1820) |

Albanian fustanella. |

Fustanella as worn by an officer of the Greek Presidential Guard, Athens. |

Fustanella worn by an Arnaut, by Jean-Léon Gérôme |

Greek revolutionary, by Dupré Louis (ca. 1820) |

Albanian warriors wearing traditional fustanella from southern Albania 1906 by Edith Durham. |

Black fustanella, worn by Greek of Macedonia region. |

Fustanella as worn by the Royal Guard of Albania in 1921. |

Warrior ("Pallikari") of Sellaida, Greece, by Dupré Louis. |

Notes

- ↑ Smithsonian Institution and Mouseio Benakē (1959). Greek Costumes and Embroideries, from the Benaki Museum, Athens: An Exhibition Presented Under the Patronage of H.M. Queen Frederika of the Hellenes. Smithsonian Institution. p. 8.

- ↑ Notopoulos, James A. (1964). "Akritan Ikonography on Byzantine Pottery". Hesperia 33 (2): 108–133. doi:10.2307/147182. ISSN 0018-098X. http://www.jstor.org/pss/147182.

- ↑ Kazhdan, Alexander P. (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 0195046528.

- ↑ Ethniko Historiko Mouseio (Greece), Maria Lada-Minōtou, I. K. Mazarakēs Ainian, Diana Gangadē, and Historikē kai Ethnologikē Hetaireia tēs Hellados (1993). Greek Costumes: Collection of the National Historical Museum. Historical and Ethnological Society of Greece. p. xxx.

- ↑ James P. Verinis, "Spiridon Loues, the Modern Foustanéla, and the Symbolic Power of Pallikariá at the 1896 Olympic Games", Journal of Modern Greek Studies 23:1 (May 2005), pp. 139-175.

- ↑ Nasse, George Nicholas (1964). The Italo-Albanian Villages of Southern Italy. National Academies. p. 38.

- ↑ Gjergji, p.20

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Konitza pp. 85-86

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Konitza, p. 67.

- ↑ Institute of Modern Greek Studies (Thessaloniki) (1999). Λεξικό της Κοινής Νεοελληνικής. Aristotelion Panepistimio Thessaloniki. ISBN 9602310855.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary; Babiniotis, Λεξικό της Νέας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας.

Further reading

- Gjergji, Andromaqi. Albanian Costumes through the Centuries: Origin, Types, Evolution. Mësonjëtorja, 2004, ISBN 9994361449.

- Gjergji, Andromaqi (1988) (in Albanian). Veshjet shqiptare në shekuj: origjina, tipologjia, zhvillimi. Tirana: Naim Frasheri.

- Konitza, Faik (1957). Albania: The Rock Garden of Southeastern Europe, and other Essays. Vatra. http://books.google.com/?id=3YRxQgAACAAJ&dq. Retrieved 2010-06-10.