Folk music

| Folk music | |

|---|---|

Béla Bartók recording Slovak peasant singers in 1908 |

|

| Traditions | List of folk music traditions |

| Musicians | List of folk musicians. |

| Instruments | Folk instruments |

Folk music is a term for musical folklore which originated in the 19th century. It has been defined in several ways: as music transmitted by word of mouth, as music of the lower classes, and as music with no known composer. It has been contrasted with commercial and classical styles. Since the middle of the 20th century, the term has also been used to describe a kind of popular music that is based on traditional music.[1] Fusion genres include folk rock, electric folk, folk metal, and progressive folk music.

Contents |

Origins and definitions

Throughout most of human prehistory and history, listening to recorded music was not possible, and the work of economic production was often manual and communal. Music was made by common people during both their work and leisure. Manual labor often included singing by the workers, which served several practical purposes. It reduced the boredom of repetitive tasks, it kept the rhythm during synchronized pushes and pulls, and it set the pace of many activities such as planting, weeding, reaping, threshing, weaving, and milling. In leisure time, singing and playing musical instruments were common forms of entertainment and history-telling—even more common than today, when electrically enabled technologies and widespread literacy make other forms of entertainment and information-sharing competitive. [2]

The terms folk music, folk song, and folk dance are comparatively recent expressions. They are extensions of the term folk lore, which was coined in 1846 by the English antiquarian William Thoms to describe "the traditions, customs, and superstitions of the uncultured classes."[3] The term is further derived from the German expression Volk, in the sense of "the people as a whole" as applied to popular and national music by Johann Gottfried Herder and the German Romantics over half a century earlier.[4]

A literary interest in the popular ballad was not new: it dates back to Thomas Percy and William Wordsworth. English Elizabethan and Stuart composers had often evolved their music from folk themes, the classical suite was based upon stylised folk-dances and Franz Josef Haydn's use of folk melodies is noted. But the emergence of the term "folk" coincided with an "outburst of national feeling all over Europe" that was particularly strong at the edges of Europe, where national identity was most asserted. Nationalist composers emerged in Eastern Europe, Russia, Scandinavia, Spain and Britain: the music of Dvorak, Smetana, Grieg, Rimsky-Korsakov, Brahms, Liszt, de Falla, Wagner, Sibelius, Vaughan Williams, Bartók and many others drew upon folk melodies. The English term "folklore", to describe traditional music and dance, entered the vocabulary of many continental European nations, each of which had its folk-song collectors and revivalists.[3]

However, despite the assembly of an enormous body of work over some two centuries, there is still no certain definition of what folk music (or folklore, or the folk) is.[5] Folk music may tend to have certain characteristics[3] but it cannot clearly be differentiated in purely musical terms. One meaning often given is that of "old songs, with no known composers"[6], another is that of music that has been submitted to an evolutionary "process of oral transmission.... the fashioning and re-fashioning of the music by the community that give it its folk character."[7] Such definitions depend upon "(cultural) processes rather than abstract musical types...", upon "continuity and oral transmission...seen as characterizing one side of a cultural dichotomy, the other side of which is found not only in the lower layers of feudal, capitalist and some oriental societies but also in 'primitive' societies and in parts of 'popular cultures'."[8]

For Scholes,[3] as for Cecil Sharp and Béla Bartók,[9] there was a sense of the music of the country as distinct from that of the town. Folk music was already "seen as the authentic expression of a way of life now past or about to disappear (or in some cases, to be preserved or somehow revived),"[10] particularly in "a community uninfluenced by art music"[7] and by commercial and printed song. Lloyd rejected this in favour of a simple distinction of economic class[9] yet for him too folk music was, in Charles Seeger's words, "associated with a lower class in societies which are culturally and socially stratified, that is, which have developed an elite, and possibly also a popular, musical culture." In these terms folk music may be seen as part of a "schema comprising four musical types: 'primitive' or 'tribal'; 'elite' or 'art'; 'folk'; and 'popular'."[11]

Revivalists' opinions differed over the origins of folk music: it was said by some to be art music changed and probably debased by oral transmission, by others to reflect the character of the race that produced it.[3] Traditionally, the cultural transmission of folk music is through playing by ear, although notation may also be used. The competition of individual and collective theories of composition set different demarcations and relations of folk music with the music of tribal societies on the one hand and of "art" and "court" music on the other. The traditional cultures that did not rely upon written music or had less social stratification could not be readily categorised. In the proliferation of popular music genres, some music became categorised as "World music" and "Roots music".

The distinction between "authentic" folk and national and popular song in general has always been loose, particularly in America and Germany[3] - for example popular songwriters such as Stephen Foster could be termed "folk" in America.[12] The International Folk Music Council definition allows that the term "can also be applied to music which has originated with an individual composer and has subsequently been absorbed into the unwritten, living tradition of a community. But the term does not cover a song, dance, or tune that has been taken over ready-made and remains unchanged."[13]

The post World War 2 folk revival in America and in Britain brought a new meaning to the word. Folk was seen as a musical style, the ethical antithesis of commercial "popular" or "pop" music, while the Victorian appeal of the "Volk" was often regarded with suspicion. The popularity of "contemporary folk" recordings caused the appearance of the category "Folk" in the Grammy Awards of 1959: in 1970 the term was dropped in favour of "Best Ethnic or Traditional Recording (including Traditional Blues)", while 1987 brought a distinction between "Best Traditional Folk Recording" and "Best Contemporary Folk Recording". The term "folk", by the start of the 21st century, could cover "singer song-writers, such as Donovan and Bob Dylan, who emerged in the 1960s and much more"[6] or perhaps even "a rejection of rigid boundaries, preferring a conception, simply of varying practice within one field, that of 'music'."[11]

Africa

Asia

Many Asian civilisations distinguish between art/court/classical styles and "folk" music, though cultures that do not depend greatly upon notation and have much anonymous art music must distinguish the two in different ways from those suggested by western scholars.

Europe and America

Celtic traditional music

Celtic music is a term used by artists, record companies, music stores and music magazines to describe a broad grouping of musical genres that evolved out of the folk musical traditions of the Celtic peoples of Western Europe. These traditions include Irish, Scottish, Manx, Cornish, Welsh, Breton traditions. Galician music is often included, though significant research showing that this has any close musical relationship is lacking. Brittany's Folk revival began in the 1950s with the "bagadoù" and the "kan-ha-diskan" before growing to world fame through Alan Stivell's work since the mid-1960s.[14]

In Ireland, The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem (although its members were all Irish-born, the group became famous while based in New York's Greenwich Village), The Dubliners, Clannad, Planxty, The Chieftains, The Pogues, The Irish Rovers, and a variety of other folk bands have done much over the past few decades to revitalise and re-popularise Irish traditional music. These bands were rooted, to a greater or lesser extent, in a living tradition of Irish music and benefited from the efforts of artists such as Seamus Ennis and Peter Kennedy.[14]

Eastern Europe

During the Communist era national folk dancing was actively promoted by the state. Dance troupes from Russia and Poland toured Western Europe from about 1937 to 1990. The Red Army Choir recorded many albums. A female choir from Bulgarian State Radio recorded "Le Mystere des Voix Bulgares" which was promoted by British DJ John Peel.

The Hungarian group Muzsikás played numerous American tours and participated in the Hollywood movie The English Patient while the singer Márta Sebestyén worked with the band Deep Forest. The Hungarian táncház movement, started in the 1970s, involves strong cooperation between musicology experts and enthusiastic amateurs. However, the traditional Hungarian folk music and folk culture barely survived in some rural areas, and it has also begun to disappear in Romania.

The movement revived broader folk traditions of music, dance, and costume together and created a new kind of music club. The movement spread to ethnic Hungarian communities around the world. Today, almost every major city in the U.S. and Australia has its own Hungarian folk music and folk dance group; there are also groups in Japan, Hong Kong, Argentina and Western Europe.

Balkan music

The Balkan folk music was influenced by the mingling of Balkan ethnic groups in the period of Ottoman Empire. It comprises the music of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro, Serbia, Slovenia, Republic of Macedonia, Albania, Turkey, the historical states of Yugoslavia or the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro and geographical regions such as Thrace. Some music is characterised by complex rhythm. An important part of the whole Balkan folk music is the music of the local Romani ethnic minority.

Notable venues

It is sometimes claimed that the earliest folk festival was the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival, 1928, in Asheville, North Carolina, founded by Bascom Lamar Lunsford. Sidmouth Festival began in 1954, and Cambridge Folk Festival began in 1965. The Cambridge Folk Festival in Cambridge, England is noted for having a very wide definition of who can be invited as folk musicians. The "club tents" allow attendees to discover large numbers of unknown artists, who, for ten or 15 minutes each, present their work to the festival audience.

Folk music is still popular among some audiences today, with folk music clubs meeting to share traditional-style songs, and there are major folk music festivals in many countries, e.g. the Woodford Folk Festival, National Folk Festival and Port Fairy Folk Festival are amongst Australia's largest major annual events, attracting top international folk performers as well as many local artists. This includes the music of Americana, Naturalismo, Bonnie "Prince" Billy, Devendra Banhart and others.

Anti-folk now has a home at the Antihootenany in the East Village, where artists like Beck, Regina Spektor, the Moldy Peaches and Nellie McKay got their starts.

European folk revival

The first folk revival influenced western classical music. Such composers as Percy Grainger, Ralph Vaughan Williams and Béla Bartók, made field recordings or transcriptions of folk singers and musicians.

In Spain Isaac Albéniz (1860–1909) produced piano works reflect his Spanish heritage, including the Suite Iberia (1906–1909). Enrique Granados (1867–1918) composed zarzuela, Spanish light opera, and Danzas Españolas - Spanish Dances. Manuel de Falla (1876–1946) became interested in the cante jondo of Andalusian flamenco, the influence of which can be strongly felt in many of his works, which include Nights in the Gardens of Spain and Siete canciones populares españolas ("Seven Spanish Folksongs", for voice and piano). Composers such as Fernando Sor and Francisco Tarrega established the guitar as Spain's national instrument. Modern Spanish Folk artists abound (Mil i Maria, Russian Red et al.) modernizing whilst respecting the traditions of their forebears.

Flamenco grew in popularity through the 20th century, as did northern styles such as the Celtic music of Galicia. French classical composers, from Bizet to Ravel, also drew upon Spanish themes, and distinctive Spanish genres became universally recognised.

Folk revival of the 1950s in Britain and America

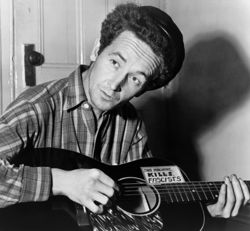

While the Romantic nationalism of the folk revival had its greatest influence on art-music, the "second folk revival" of the later 20th century brought a new genre of popular music with artists marketed by amplified concerts, recordings and broadcasting. The American Woody Guthrie collected folk music in the 1930s and 1940s and also composed his own songs, as did Pete Seeger. In the 1930s Jimmie Rodgers, in the 1940s Burl Ives and in the 1950s Seeger's group The Weavers, Harry Belafonte, The Kingston Trio, and The Limeliters found a popularity that culminated in the Hootenanny television series[15] and the associated magazine ABC-TV Hootenanny in 1963–1964. Sing Out! magazine helped spread both traditional and composed songs, as did folk-revival-oriented record companies.

In the 1960s, folk singers and songwriters such as Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, and Tom Paxton followed in Guthrie's footsteps, writing "protest music" and topical songs and expressing support for the American Civil Rights Movement. The Canadians Gordon Lightfoot, Leonard Cohen, Bruce Cockburn and Joni Mitchell were all invested with the Order of Canada. Dylan's use of electric instruments helped inaugurate the genres of folk rock and country rock, particularly by his album John Wesley Harding and his support for the music of The Band. Many of the acid rock bands of San Francisco began by playing acoustic folk and blues.

In 1950 Alan Lomax came to Britain and met A.L.'Bert' Lloyd and Ewan MacColl, a meeting credited as inaugurating the second British folk revival. In London the colleagues opened The Ballads and Blues Club, eventually renamed the Singers' Club, possibly the first folk club: it closed in 1991. As the 1950s progressed into the 1960s, the folk revival movement built up in both Britain and America.

In the United Kingdom, the folk revival fostered young artists like The Watersons, Martin Carthy and Roy Bailey and a generation of singer-songwriters such as Bert Jansch, Ralph McTell, Donovan and Roy Harper. Bob Dylan, Paul Simon and Tom Paxton visited Britain for some time in the early 1960s, the first two, particularly, making later use of the traditional English material they heard.

The late 1960s saw the advent of electric folk groups, a key moment being the release of Fairport Convention's album Liege and Lief. Guitarist Richard Thompson declared that the music of The Band demanded a corresponding "English Electric" style, while bassist Ashley Hutchings formed Steeleye Span in order to pursue a wholly traditional repertoire. In the second half of the 1990s, once more, folk music made an impact on the mainstream music via a younger generation of artists such as Eliza Carthy, Kate Rusby and Spiers and Boden.

Popular subgenres

Contemporary country music descends ultimately from a rural American folk tradition, but has evolved. Bluegrass music is a professional development of American old time music, intermixed with blues and jazz. Exponents of electric folk music such as Fairport Convention, Pentangle, Alan Stivell, Mr. Fox and Steeleye Span saw electrification of traditional musical forms as a means to reach a far wider audience. Traditional folk music merged with rock and roll to form folk rock performers such as The Byrds, Simon & Garfunkel and The Mamas & the Papas. Since the 1970s a genre of "contemporary folk" fueled by new singer-songwriters has continued with such artists as Chris Castle, Steve Goodman, and John Prine. The Pogues and Ireland's The Corrs brought traditional tunes back into the album charts.

In the 1980s artists like Phranc and The Knitters propagated cowpunk or folk punk, which eventually evolved into alt country. More recently the same spirit has been embraced and expanded on by performers such as Dave Alvin, Miranda Stone and Steve Earle.

Hard rock and heavy metal bands such as Korpiklaani, Skyclad, Waylander and Finntroll meld elements from a wide variety of traditions, including in many cases instruments such as fiddles, tin whistles, accordions and bagpipes. Folk metal often favours pagan-inspired themes. Black metal and Viking metal are defined on their folk stance, incorporating folk interludes into albums (e.g., Bergtatt and Kveldssanger, the first two albums by once-black metal, now-experimental band Ulver).

Filk music can be considered folk music stylistically and culturally (though the 'community' it arose from, science fiction fandom, is an unusual and thoroughly modern one).[16] Neofolk began in the 1980s, fusing traditional European folk music with post-industrial music, historical topics, philosophical commentary, traditional songs and paganism. The genre is largely European.

Anti folk, began in New York City in the 1980s. Folk punk, known in its early days as rogue folk, is a fusion of folk music and punk rock. It was pioneered by the London-based Irish band The Pogues in the 1980s. Radical folk of the present claims to tackle age old political issues such as workers rights and capital punishment. It is represented by groups such as such as The Last Internationale of New York.

Other subgenres include:

- Indie folk

- Techno-folk

- Industrial folk music

- Freak folk

Media

See also

- Roud Folk Song Index

- World music

References

Notes

- ↑ http://folkmusic.about.com/od/glossary/g/FolkMusic.htm About.com definition

- ↑ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hr9FP93o8Ro Alan Lomax's 1947 Documentary narrated by Pete Seeger

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Percy Scholes, The Oxford Companion to Music, OUP 1977, article "Folk Song".

- ↑ A.L.Lloyd, Folk Song in England, Panther Arts, 1969, page 13.

- ↑ Richard Middleton, Studying Popular Music, Philadelphia: Open University Press (1990/2002). ISBN 0-335-15275-9, p. 127.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ronald D. Cohen Folk music: the basics (CRC Press, 2006), pp. 1-2

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 International Folk Music Council definition (1954/5), given in Lloyd (1969) and Scholes (1977).

- ↑ Charles Seeger (1980), citing the approach of Redfield (1947) and Dundes (1965), quoted in Middleton (1990) p.127

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 A.L.Lloyd, Folk Song in England, Panther Arts, 1969, page 14-5.

- ↑ Middleton 1990, p.127.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Charles Seeger (1980) quoted in Middleton (1990) p.127

- ↑ Example given by both Scholes (1977) and Lloyd (1969)

- ↑ Quoted by both Scholes (1977) and Lloyd (1969)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Sawyers, June Skinner (2000). Celtic Music: A Complete Guide. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81007-7.

- ↑ http://www.tvtome.com/Hootenanny/ TVtome.com Retrieved on 05-03-07

- ↑ Hall of Fame acceptance speeches by Sally and Barry Childs-Helton

Further reading

- Farsani, Mohsen (2003) Lamentations chez les nomades bakhtiari d'Iran. Paris: Université Sorbonne Nouvelle.

- Bayard, Samuel Preston (1950). "Prolegomena to a Study of the Principal Melodic Families of British-American Folksong", Journal of American Folklore pp. 1–44. Reprinted in McAllester, David Park (ed.) (1971) Readings in ethnomusicology New York: Johnson Reprint. OCLC 2780256

- Bearman, C. J. (2000). "Who Were the Folk? The Demography of Cecil Sharp's Somerset Folk Singers." The Historical Journal (September 2000) Vol. 43 No.3 pp. 751–75. JSTOR 3020977

- Bevil, Jack Marshall (1984). Centonization and Concordance in the American Southern Uplands Folksong Melody: A Study of the Musical Generative and Transmittive Processes of an Oral Tradition. PhD Thesis, North Texas University, Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International. OCLC 12903203

- Bevil, Jack Marshall (1986). "Scale in Southern Appalachian Folksong: a Reexamination", College Music Symposium Vol. 26, 77-91.

- Bevil, Jack Marshall (1987). "A Paradigm of Folktune Preservation and Change Within the Oral Tradition of a Southern Appalachian Community, 1916-1986." Unpublished. Read at the 1987 National Convention of the American Musicological Society, New Orleans.

- Carson, Ciaran (1997). Last Night's Fun: In and Out of Time with Irish Music. North Point Press. ISBN 9780865475151

- Cartwright, Garth (2005). Princes Amongst Men: Journeys with Gypsy Musicians. London: Serpent's Tail. ISBN 1852428775

- Cowdery, James R. (1990). The Melodic Tradition of Ireland. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press. ISBN 9780873384070

- Harker, David (1985). Fakesong: The Manufacture of British 'Folksong', 1700 to the Present Day. Milton Keynes [Buckinghamshire]; Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 0335150667

- Hogeland, William (2004). "Emulating the Real and Vital Guthrie, Not St. Woody". New York Times (March 14).

- Jackson, George Pullen (1933). White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands: The Story of the Fasola Folk, Their Songs, Singings, and "Buckwheat Notes". Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. LCCN 33-003792 OCLC 885331 Reprinted by Kessinger Publishing (2008) ISBN 9781436690447

- Keller, Marcello Sorce (1984). "The Problem of Classification in Folksong Research: A Short History", Folklore Vol. 95, no. 1:100–104. JSTOR 1259763

- Matthews, Scott (2008). "John Cohen in Eastern Kentucky: Documentary Expression and the Image of Roscoe Halcomb During the Folk Revival". Southern Spaces. http://www.southernspaces.org/contents/2008/matthews/1a.htm. (August 6)

- Middleton, Richard (1990). Studying Popular Music. Milton Keynes; Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 0-335-15276-7 (cloth), ISBN 0-335-15275-9 (pbk).

- Mills, Isabelle (1974). The Heart of the Folk Song, Canadian Journal for Traditional Music Vol. 2

- Pegg, Carole (2001). "Folk Music". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan.

- Scully, Michael F. (2008). The Never-Ending Revival: Rounder Records and the Folk Alliance. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Warren-Findley, Jannelle (1980). "Journal of a Field Representative : Charles Seeger and Margaret Valiant" Ethnomusicology, Vol. 24, No. 2 (May, 1980), pp. 169–210 JSTOR 851111

- van der Merwe, Peter (1989). Origins of the Popular Style: The Antecedents of Twentieth-Century Popular Music. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-316121-4.

External links

- http://www.dailymotion.com/group/musictrad - the channel TV of traditional music

- The World and Traditional Music section at the British Library Sound Archive

- The Traditional Music in England project, World and Traditional Music section at the British Library Sound Archive

- The Mudcat Cafe and Digital Tradition song database

- An article on folk music from the Encyclopedia of Music in Canada

- Welsh Folk-Song Society

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - Folk Music

- Folk Music-A Blog features folk songs & folk artists around the world.

- The Crooked Road: Heritage music trail-A famous 243-mile experience where folk and bluegrass music originated.

- Folk Alley A Non-Profit Listener Supported Folk Music Resource, Streaming online since 2004

- www.folklyrics.net Traditional songs - Folk song lyrics of the world

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||