Faroe Islands

| Faroe Islands

Føroyar

Færøerne |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: Tú alfagra land mítt Thou, my most beauteous land |

||||||

|

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Tórshavn |

|||||

| Official language(s) | Faroese, Danish | |||||

| Ethnic groups | 91.7% Faroese 5.8% Danish 0.4% Icelanders 0.2% Norwegian 0.2% Poles |

|||||

| Demonym | Faroese | |||||

| Government | Parliamentary democracy within a constitutional monarchy | |||||

| - | Monarch | Margrethe II | ||||

| - | High Commissioner | Dan M. Knudsen | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Kaj Leo Johannesen | ||||

| Autonomous constituent country within the Kingdom of Denmark |

||||||

| - | Unified with Norway[a] | 1035 | ||||

| - | Ceded to Denmark[b] | 14 January 1814 | ||||

| - | Home rule | 1 April 1948 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 1,399 km2 (180th) 540 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 0.5 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | June 2010 estimate | 48,805 [1] (205th) | ||||

| - | 2007 census | 48,760 | ||||

| - | Density | 35/km2 (171st) 91/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2008 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $1.56 billion (not ranked) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $32,000 (not ranked) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2008 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $2.45 billion (not ranked) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $50,300 (not ranked) | ||||

| HDI (2006) | 0.943[c] (high) (15th) | |||||

| Currency | Faroese króna[d] (DKK) |

|||||

| Time zone | GMT | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | EST (UTC+1) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .fo | |||||

| Calling code | 298 | |||||

| a. ^ Danish monarchy reached the Faeroes in 1380 with the reign of Olav IV in Norway. b. ^ The Faeroes, Greenland and Iceland were formally Norwegian possessions until 1814 despite 400 years of Danish monarchy beforehand. |

||||||

.jpg)

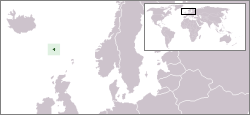

The Faroe Islands (Faroese: Føroyar, Danish: Færøerne) are an island group situated between the Norwegian Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean, approximately halfway between Great Britain and Iceland. The Faroe Islands are a constituent country of the Kingdom of Denmark, along with Denmark proper and Greenland.

The Faroe Islands have been an autonomous province of the Kingdom of Denmark since 1948. Over the years, the Faroese have been granted control of most matters. Some areas still remain the responsibility of Denmark, such as military defence and foreign affairs.

The Faroe Islands were politically associated with Denmark in 1380, when Norway entered the Kalmar Union with Denmark and Sweden, which gradually evolved into Danish control of the islands, but this association ceased in 1814. The Faroe Islands have two representatives on the Nordic Council, as members of the Danish delegation.

Contents |

History

The early history of the Faroe Islands is not well known, although Gael hermits and monks from a Hiberno-Scottish mission are believed by some to have settled in the 6th century, introducing sheep and goats and the early Goidelic language to the islands; however this is just speculation. Saint Brendan, an Irish monastic saint, who is supposed to have lived around 484–578, is said to have visited the Faroe Islands on two or three occasions (512–530), naming two of the islands Sheep Island and Paradise Island of Birds.

Later (c. 650) Norsemen also settled the islands, bringing to the islands the Old Norse language which evolved into the modern Faroese language spoken today.

The settlers are not thought to have come directly from Scandinavia, but rather they were Norse settlers from Shetland and Orkney, and Norse-Gaels from the areas surrounding the Irish Sea and Western Isles of Scotland. The old Gaelic name for the Faroe Islands Na Scigirí means the Skeggjar and probably refers to the Eyja-Skeggjar (Island-Beards), a nickname given to the island dwellers. The aforementioned theories though are speculative at best and are not currently supported by archeological evidence. However, the establishment of Norwegian Vikings is well documented.[2] Thus, according to the Faroe Islands Government, the Nordic language and culture are derived from the Norwegian, or Norsemen, that settled in the Faroe Islands.[3]

According to Færeyinga Saga, emigrants who left Norway to escape the tyranny of Harald I of Norway settled on the islands around the end of the 9th century. Early in the 11th century, Sigmundur Brestirson – whose clan had flourished in the southern islands but had been almost exterminated by invaders from the northern islands – escaped to Norway and was sent back to take possession of the islands for Olaf Tryggvason, King of Norway. He introduced Christianity and, though he was subsequently murdered, Norwegian supremacy was upheld. Norwegian control of the islands continued until 1380, when Norway entered the Kalmar Union with Denmark, which gradually evolved into Danish control of the islands. The Reformation reached the Faroes in 1538. When the union between Denmark and Norway was dissolved as a result of the Treaty of Kiel in 1814, Denmark retained possession of the Faroe Islands.

The trade monopoly in the Faroe Islands was abolished in 1856 and the area has since then developed as a modern fishing nation with its own fleet. The national awakening since 1888 was initially based on a struggle for the Faroese language and was thus culturally oriented, but after 1906 it was more and more politically oriented, with the foundation of the political parties of the Faroe Islands.

On 12 April 1940, the Faroes were occupied by British troops. The move followed the invasion of Denmark by Nazi Germany and had the objective of strengthening British control of the North Atlantic (see Second Battle of the Atlantic). In 1942–1943 the British Royal Engineers built the only airport in the Faroes, Vágar Airport. Control of the islands reverted to Denmark following the war, but in 1948 home-rule was introduced, with a high degree of local autonomy. In 1973 the Faroe Islands declined to join Denmark in entering the European Community (now European Union). The islands experienced considerable economic difficulties following the collapse of the fishing industry in the early 1990s, but have since made efforts to diversify the economy. Support for independence has grown and is the objective of the Republican Party.

Politics

The Faroese government holds executive power in local government affairs. The head of the government is called the Løgmaður (literally 'law person') or prime minister in English. Any other member of the cabinet is called a landsstýrismaður ('national committee man'). Today, elections are held in the municipalities, on a national level for the Løgting ('law assembly'), and for the Danish Folketing. For the Løgting elections there are seven electoral districts, each one comprising a sýsla, while Streymoy is divided into a northern and southern part (Tórshavn region).

The Faroes and Denmark

The Faroe Islands have been under the control of Denmark since 1388. The Treaty of Kiel in 1814 terminated the Danish-Norwegian union and Norway came under the rule of the King of Sweden, while the Faroe Islands, Iceland, and Greenland remained possessions of Denmark. Subsequently, the Løgting was abolished in 1816, and the Faroe Islands were to be governed as an ordinary Danish amt (county), with the Amtmand as its head of government. In 1851 the Løgting was reinstated, but served mainly as an advisory body until 1948.

At the end of the Second World War some of the population favored independence from Denmark, and on 14 September 1946 a referendum was held on the question of secession. It was a consultative referendum: the parliament was not bound to follow the people's vote. This was the first time that the Faroese people had been asked whether they favored independence or wanted to continue as a part of the Danish kingdom. The result of the vote was a narrow majority in favor of secession, but the coalition in parliament could not reach agreement on how this outcome should be interpreted and implemented; and because of these irresoluble differences, the coalition fell apart. A parliamentary election was held just a few months later, in which the political parties that favored staying in the Danish kingdom increased their share of the vote and formed a coalition. Based on this, they chose to reject secession. Instead, a compromise was made and the Folketing passed a home-rule law, which came into effect in 1948. The Faroe Islands' status as a Danish amt was thereby brought to an end; the Faroe Islands were given a high degree of self-governance, supported by a substantial financial subsidy from Denmark.

At present the islanders are about evenly split between those favoring independence and those who prefer to continue as a part of the Kingdom of Denmark. Within both camps there is a wide range of opinions. Of those who favor independence, some are in favor of an immediate unilateral declaration. Others see it as something to be attained gradually and with the full consent of the Danish government and the Danish nation. In the unionist camp there are also many who foresee and welcome a gradual increase in autonomy even while strong ties with Denmark are maintained.

The Faroes and the European Union

As explicitly asserted by both Rome treaties, the Faroe Islands are not part of the European Union. Moreover, a protocol to the treaty of accession of Denmark to the European Communities stipulates that Danish nationals residing in the Faroe Islands are not to be considered as Danish nationals within the meaning of the treaties. Hence, Danish people living in the Faroes are not citizens of the European Union (although other EU nationals living there remain EU citizens). The Faroes are not covered by the Schengen free movement agreement, but there are no border checks when travelling between the Faroes and any Schengen country. (The Faroes have been part of the Nordic Passport Union since 1966, and since 2001 there have been no border checks between the Nordic countries and the rest of the Schengen area as part of the Schengen agreement.) [4]

Regions and municipalities

Administratively, the islands are divided into 34 municipalities (kommunur) within which there are 120 or so settlements.

Traditionally, there are also the six sýslur ("regions": Norðoyar, Eysturoy, Streymoy, Vágar, Sandoy and Suðuroy). Although today sýsla technically means "police district", the term is still commonly used to indicate a geographical region. In earlier times, each sýsla had its own ting (assembly), the so-called várting ("spring assembly").

Geography

The Faroe Islands are an island group consisting of 18 major islands about 655 kilometres (407 mi) off the coast of Northern Europe, between the Norwegian Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean, about halfway between Iceland and Norway, the closest neighbours being the Northern and Western Isles of Scotland. Its coordinates are .

Its area is 1,399 square kilometres (540 sq. mi), and it has no major lakes or rivers. There are 1,117 kilometres (694 mi) of coastline.[5] The only major island that is uninhabited is Lítla Dímun.

The islands are rugged and rocky with some low peaks; the coasts are mostly cliffs. The highest point is Slættaratindur, 882 metres (2,894 ft) above sea level. There are also areas below sea level.

The Faroe Islands are dominated by tholeiitic basalt lava which was part of the great Thulean Plateau during the Paleogene period.[6]

Distances to nearest countries and islands

- North Rona, Scotland (uninhabited): 260 kilometres (160 mi)

- Shetland (Foula) (Scotland): 285 kilometres (177 mi)

- Mainland Scotland: 310 kilometres (190 mi)

- Denmark: 990 kilometres (620 mi)

Distances to the nearest cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants

- Aberdeen, Scotland 540 kilometres (340 mi)

- Dundee, Scotland 600 kilometres (370 mi)

- Bergen, Norway 655 kilometres (407 mi)

- Glasgow, Scotland 670 kilometres (420 mi)

- Reykjavík, Iceland 797 kilometres (495 mi)

- Aalborg, Denmark 1,091 kilometres (678 mi)

- Copenhagen, Denmark 1,310 kilometres (810 mi)

Economy

Economic troubles caused by a collapse of the Faroese fishing industry in the early 1990s brought high unemployment rates of 10 to 15% in the mid 1990s.[7] Unemployment decreased in the later 1990s, down to about 6% at the end of 1998.[7] By June 2008 unemployment had declined to 1.1%, before rising to 3.4% in early 2009.[7] Nevertheless, the almost total dependence on fishing and fish farming means that the economy remains extremely vulnerable. The Faroes and Greenland have refused to abide by quotas set by the North Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO), which sets catch limits for each member. Petroleum found close to the Faroese area gives hope for deposits in the immediate area, which may provide a basis for sustained economic prosperity.

20% of Faroe Islands' national budget comes as economic aid from Denmark, which is about the same as 50% of Faroe Islands' total expense budget.[8]

Since 2000, new information technology and business projects have been fostered in the Faroe Islands to attract new investment. The introduction of Burger King in Tórshavn was widely publicized and a sign of the globalization of Faroese culture. It is not yet known whether these projects will succeed in broadening the islands' economic base. The islands have one of the lowest unemployment rates in Europe, but this should not necessarily be taken as a sign of a recovering economy, as many young students move to Denmark and other countries once they have left high school. This leaves a largely middle-aged and elderly population that may lack the skills and knowledge to fill newly developed positions on the Faroes. In 2008, the Faroes made a $52 million loan to Iceland, in the light of that country's banking woes.[9]

On 5 August 2009, two opposition parties introduced a bill in the Løgting to adopt the Euro as the national currency, pending a referendum.[10]

Transportation

Vágar Airport has scheduled services from Vágar Island. The largest Faroese airline is Atlantic Airways.

Due to the rocky terrain and relatively small size of the Faroe Islands, its transportation system was not as extensive as in other places of the world. This situation has now changed, and the infrastructure has been developed extensively. Some 80% of the population of the islands is connected by tunnels through the mountains and between the islands, bridges and causeways which link the three largest islands and three other large islands to the northeast together, while the other two large islands to the south of the main area are connected to the main area with new fast ferries. There are good roads to every village in the islands, except for seven of the smaller islands, six of which only have one village.

Demographics

The vast majority of the population are ethnic Faroese, of Norse and Celtic descent.[11]

Recent DNA analyses have revealed that Y chromosomes, tracing male descent, are 87% Scandinavian.[12] The studies show that mitochondrial DNA, tracing female descent, is 84% Scottish / Irish.[13]

Of the approximately 48,000 inhabitants of the Faroe Islands (16,921 private households (2004)), 98% are citizens of the Kingdom of Denmark, including Faroese, Danish and Greenlandic people. One can analyse the inhabitants by place of birth, as follows: born on the Faroes 91.7%, in Denmark 5.8% and in Greenland 0.3%. The largest group of foreigners is Icelanders, comprising 0.4% of the population, followed by Norwegians and Polish, each comprising 0.2%. Altogether, on the Faroe Islands there are people of 77 different nationalities.

Faroese is spoken in the entire area as a first language. It is not possible to say exactly how many people worldwide speak the Faroese language. This is for two reasons: first, many ethnic Faroese live in Denmark, and few who are born there return to the Faroes with their parents or as adults; second, there are some established Danish families in the Faroes who speak Danish at home.

The Faroese language is one of the least spoken of the Germanic languages. Faroese grammar as well as vocabulary is most similar to Icelandic and to the extinct language Old Norse. In contrast, spoken Faroese is very different from Icelandic and is closer to Norwegian dialects of the west coast of Norway. While Faroese is the main language in the islands, both Faroese and Danish are official languages.[14]

Faroese language policy provides for the active creation of new terms in Faroese suitable for modern life.

Population trends (1327–2004)

If the first inhabitants of the Faroe Islands were Irish monks, then they must have lived as a very small group of settlers. Later, when the Vikings colonised the islands, there was a considerable increase in the population. However, it never exceeded 5,000 until the 18th century. Around 1349, about half of the islands' people died of the Black Death plague.

Only with the rise of the deep sea fishery (and thus independence from agriculture in the islands' harsh terrain) and with general progress in the health service was rapid population growth possible in the Faroes. Beginning in the 18th century, the population increased tenfold in 200 years.

At the beginning of the 1990s, the Faroe Islands entered a deep economic crisis leading to heavy emigration; however, this trend reversed in subsequent years to a net immigration.

|

|

Urbanisation and regionalisation

The Faroese population is spread across most of the area; it was not until recent decades that significant urbanisation occurred. Industrialisation has been remarkably decentralised, and the area has therefore maintained quite a viable rural culture. Nevertheless, villages with poor harbour facilities have been the losers in the development from agriculture to fishing, and in the most peripheral agricultural areas, also known as the outer islands, there are scarcely any young people left. In recent decades, the village-based social structure has nevertheless been placed under pressure, giving way to a rise in interconnected "centres" that are better able to provide goods and services than the badly connected periphery. This means that shops and services are now relocating en masse from the villages into the centres, and slowly but steadily the Faroese population is concentrating in and around the centres.

In the 1990s the old national policy of developing the villages (Bygdamenning) was abandoned, and instead the government started a process of regional development (Økismenning). The term "region" referred to the large islands of the Faroes. Nevertheless the government was unable to press through the structural reform of merging the small rural municipalities in order to create sustainable, decentralised entities that could drive forward regional development. As regional development has been difficult on the administrative level, the government has instead made heavy investment in infrastructure, interconnecting the regions.

In general, it is becoming less valid to regard the Faroes as a society based on separate islands and regions. The huge investments in roads, bridges and sub-sea tunnels (see also Transportation in the Faroe Islands) have bound the islands together, creating a coherent economic and cultural sphere that covers almost 90% of the population. From this perspective it is reasonable to regard the Faroes as a dispersed city or even to refer to it as the Faroese Network City.

Religion

According to Færeyinga Saga, Sigmundur Brestisson brought Christianity to the islands in 999. However, archaeology at a site in Leirvík suggests that Celtic Christianity may have arrived 150 years earlier, or more. The Faroe Islands' Church Reformation was completed on 1 January 1540. According to official statistics from 2002, 84.1% of the Faroese population are members of the state church, the Faroese People's Church (Fólkakirkjan), a form of Lutheranism. Faroese members of the clergy who have had historical importance include V. U. Hammershaimb (1819–1909), Frederik Petersen (1853–1917) and, perhaps most significantly, Jákup Dahl (1878–1944), who had a great influence in ensuring that the Faroese language was spoken in the church instead of Danish.

In the late 1820s, the Christian Evangelical religious movement, the Plymouth Brethren, was established in England. In 1865, a member of this movement, William Gibson Sloan, travelled to the Faroes from Shetland. At the turn of the 20th century, the Faroese Plymouth Brethren numbered thirty. Today, approximately 10% of the Faroese population are members of the Open Brethren community (Brøðrasamkoman). About 5% belong to other Christian denominations, such as the charismatic movement. which started in the 1970s–1980s in the Faroe Islands. There are several charismatic churches around the islands, the largest of which, called Keldan (Spring Water), has about 400 to 450 members. The Adventists operate a private school in Tórshavn. Jehovah's Witnesses also number four congregations (approximately 80 to 100 members). The Roman Catholic congregation comprises approximately 170 members. The municipality of Tórshavn operates their old Franciscan school. There are also around fifteen Bahá'ís who meet at four different places. Unlike Denmark, Sweden, and Iceland with Forn Sidr, the Faroes have no organised Ásatrú community, but there is a fair share of pagan lore, song and ritual performed in individuals' houses or in public spaces, rather than in church buildings.

The best known church buildings in the Faroe Islands include St. Olaf's Church and the Magnus Cathedral in Kirkjubøur; the Vesturkirkjan and the Maria Church, both of which are situated in Tórshavn; the church of Fámjin; the octagonal church in Haldarsvík; Christianskirkjan in Klaksvík and also the two pictured here.

In 1948, Victor Danielsen (Plymouth Brethren) completed the first Bible translation into Faroese from different modern languages. Jacob Dahl and Kristian Osvald Viderø (Fólkakirkjan) completed the second translation in 1961. The latter was translated from the original Biblical languages (Hebrew and Greek) into Faroese.

Culture

Culture of the Faroe Islands has its roots in the Nordic culture. The Faroe Islands were long isolated from the main cultural phases and movements that swept across parts of Europe. This means that they have maintained a great part of their traditional culture. The language spoken is Faroese and it is one of three insular Scandinavian languages descended from the Old Norse language spoken in Scandinavia in the Viking Age, the others being Icelandic and the extinct Norn, which is thought to have been mutually intelligible with Faroese. Until the 15th century, Faroese had a similar orthography to Icelandic and Norwegian, but after the Reformation in 1538, the ruling Danes outlawed its use in schools, churches and official documents. Although a rich spoken tradition survived, for 300 years the language was not written down. This means that all poems and stories were handed down orally. These works were split into the following divisions: sagnir (historical), ævintýr (stories) and kvæði (ballads), often set to music and the mediaeval chain dance). These were eventually written down in the 19th century.

Ólavsøka

The national holiday, Ólavsøka, is on 29 July, and commemorates the death of Saint Olaf. The celebrations are held in Tórshavn. They start on the evening of the 28th and carry on until 31 July.

The official celebration starts on the 29th, with the opening of the Faroese Parliament, a custom which dates back some 900 years.[15] This begins with a service held in Tórshavn Cathedral; all members of parliament as well as civil and church officials walk to the cathedral in a procession. All of the parish ministers take turns giving the sermon. After the service, the procession returns to the parliament for the opening ceremony.

Other celebrations are marked by different kind of sports competitions, the rowing competition (in Tórshavn Harbour) being the most popular, art exhibitions, pop concerts, and the famous Faroese dance. The celebrations have many facets, and only a few are mentioned here.

People also mark the occasion by wearing the national Faroese dress.

The Nordic House in the Faroe Islands

The Nordic House in the Faroe Islands (in Faroese Norðurlandahúsið) is the most important cultural institution in the Faroes. Its aim is to support and promote Scandinavia and Faroese culture, locally and in the Nordic region. Erlendur Patursson (1913–1986), Faroese member of the Nordic Council, put forward the idea of a Nordic cultural house in the Faroe Islands. A Nordic competition for architects was held in 1977, in which 158 architects participated. Winners were Ola Steen from Norway and Kolbrún Ragnarsdóttir from Iceland. By staying true to folklore, the architects built the Nordic House to resemble an enchanted hill of elves. The house opened in Tórshavn in 1983. The Nordic House is a cultural organization under the Nordic Council of Ministers. The Nordic House is run by a steering committee of eight, of whom three are Faroese and five from other Nordic countries. There is also a local advisory body of fifteen members, representing Faroese cultural organizations. The House is managed by a director appointed by the steering committee for a four year term.

Music

The Faroe Islands have a very active music scene. The islands have their own symphony orchestra, the classical ensemble Aldubáran and many different choirs; the most well-known being Havnarkórið. The most well-known Faroese composers are Sunleif Rasmussen and the Dane Kristian Blak. Blak is also head of the record company Tutl.

The first Faroese opera was by Sunleif Rasmussen. It is entitled Í Óðamansgarði (The Madman´s Garden), and it had its premiere on 12 October 2006, at the Nordic House. The opera is based on a short story by the writer William Heinesen.

Young Faroese musicians who have gained much popularity recently are Eivør (Eivør Pálsdóttir), , Anna Katrin Egilstrøð, Lena (Lena Andersen), Teitur (Teitur Lassen), Høgni Reistrup, Høgni Lisberg and Brandur Enni.

Well-known bands include Týr, Gestir, The Ghost, Boys In A Band, ORKA, 200 and the former band Clickhaze.

The festival of contemporary and classical music, Summartónar, is held each summer. Large open-air music festivals for popular music with both local and international musicians participating are G! Festival in Gøta in July and Summarfestivalurin in Klaksvík in August.

Traditional food

Traditional Faroese food is mainly based on meat, seafood and potatoes and uses few fresh vegetables. Mutton is the basis of many meals, and one of the most popular treats is skerpikjøt, well aged, wind-dried mutton which is quite chewy. The drying shed, known as a hjallur, is a standard feature in many Faroese homes, particularly in the small towns and villages. Other traditional foods are ræst kjøt (semi-dried mutton) and ræstur fiskur, matured fish. Another Faroese specialty is Grind og spik, pilot whale meat and blubber. (A parallel meat/fat dish made with offal is garnatálg). Well into the last century, meat and blubber from a pilot whale meant food for a long time. Fresh fish also features strongly in the traditional local diet, as do seabirds, such as Faroese puffins, and their eggs. Dried fish is also commonly eaten.

There is one brewery called Föroya Bjór, which has produced beer since 1888 with exports mainly to Iceland and Denmark.A local specialty is fredrikk, a special brew, made in Nólsoy. Hard alcohol like snaps is not allowed to be produced in the Faroe Islands, hence the Faroese aqua vit, Aqua Vita, is produced abroad.

Since the friendly British occupation, the Faroese have been fond of British food, in particular fish and chips and British-style chocolate such as Cadbury Dairy Milk which is found in many of the island's shops, whereas in Denmark this is scarce.

Whaling

Records of drive hunts in the Faroe Islands date back to 1584.[16] It is regulated by Faroese authorities but not by the International Whaling Commission as there are disagreements about the Commission's legal authority to regulate small cetacean hunts. Hundreds of long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melaena) are killed every couple of years, mainly during the summer. The hunts, called "grindadráp" in Faroese, are non-commercial and are organized on a community level; anyone can participate. The hunters first surround the pilot whales with a wide semicircle of boats. Then they drive the whales slowly into a bay or to the shallows of a fjord. When a whale is in shallow water a hook is placed in its blowhole so that it may be dragged ashore. Once on land or immobilized in knee deep water, a cut is made across its top near the blowhole to severe partially its head. The dead or dying animals are then dragged further to shore after the remaining whales have been likewise killed.

Some Faroese consider the hunt an important part of their culture and history. Animal-rights groups criticize the hunt as being cruel and unnecessary, while the hunters claim in return that most journalists do not exhibit sufficient knowledge of the catch methods or its economic significance.[17][18][19]

Sport

The Faroe Islands compete in the biannual Island Games, which were hosted by the islands in 1989. 10 football teams contest the Faroe Islands Premier League, currently ranked 48th by UEFA's League coefficient. The Faroe Islands are a full member of UEFA and the Faroe Islands national football team competes in the UEFA European Football Championship. The Faroe Islands are also a full member of FIFA and therefore the Faroe Islands national football team, managed by Irish manager Brian Kerr, also competes in the FIFA World Cup qualifiers. The Faroe Islands compete in the Paralympics, but have yet to make an appearance in the Olympics, where they compete as part of Denmark.

Handcrafts

Lace knitting is a traditional handicraft. The most distinctive trait of Faroese lace shawls is the center back gusset shaping. Each shawl consists of two triangular side panels, a trapezoid-shaped back gusset, an edge treatment, and usually shoulder shaping.and the Grindaknívur

Public holidays

- See also: Public holidays in Denmark

- New Year's Day, 1 January

- Maundy Thursday

- Good Friday

- Easter Sunday

- Easter Monday

- Flag day, 25 April

- General Prayer Day (Store Bededag), 4th Friday after Easter

- Ascension Day

- Whit Sunday

- Whit Monday

- Constitution Day, 5 June (½ day holiday)

- St.Olav’s Eve, 28 July (½ day holiday)

- St.Olav’s Day, 29 July (National holiday)

- Christmas Eve, 24 December

- Christmas Day, 25 December

- Boxing Day, 26 December

- New Year’s Eve, 31 December (½ day holiday)

Climate

The climate is classed as Maritime Subarctic according to the (Köppen climate classification:Cfc). The overall character of the islands' climate is influenced by the strong warming influence of the Atlantic Ocean, which produces the North Atlantic Current. This, together with the remoteness of any sources of warm airflows, ensures that winters are mild (mean temperature 3.0 to 4.0 °C or 37 to 39°F) while summers are cool (mean temperature 9.5 to 10.5 °C or 49 to 51°F). The islands are windy, cloudy and cool throughout the year with over 260 annual rainy days. The islands lie in the path of depressions moving northeast and this means that strong winds and heavy rain are possible at all times of the year. Sunny days are rare and overcast days are common. Hurricane Faith struck the Faroe Islands on September 5, 1966 with sustained winds still over 100 mph and only then did the storm cease to be a tropical system.[20]

Flora

The natural vegetation of the Faroe Islands is dominated by Arctic-alpine plants, wildflowers, grasses, moss and lichen. Most of the lowland area is grassland and some is heath, dominated by shrubby heathers, mainly Calluna vulgaris. Among the numerous herbaceous flora that occur in the Faroe Islands is the Marsh Thistle, Cirsium palustre.

Faroe is characterised by the lack of trees, resembling Connemara and Dingle in Ireland and the Scottish islands.

A few small plantations consisting of plants collected from similar climates like Tierra del Fuego in South America and Alaska thrive on the islands.

Fauna

Birds

The bird fauna of the Faroe Islands is dominated by sea-birds and birds attracted to open land like heather, probably due to the lack of woodland and other suitable habitats. Many species have developed special Faroese sub-species: Common Eider, European Starling, Winter Wren, Common Guillemot, and Black Guillemot.[21] The Pied Raven was endemic to the Faroe Islands, but has now become extinct.

Mammals

Only a few species of wild land mammals are found in the Faroe Islands today, all introduced by humans. Three species are thriving on the islands today: Mountain Hare (Lepus timidus), Brown Rat (Rattus norvegicus) and the House Mouse (Mus domesticus). Apart from the local domestic sheep breed called Faroes, a variety of feral sheep survived on Little Dímun until the mid 1800s.[22]

Grey Seals (Halichoerus grypus) are very common around the shorelines.

Several species of cetacean live in the waters around the Faroe Islands. Best known are the Long-finned Pilot Whales (Globicephala melaena), which are still annually slaughtered by the islanders in accordance with longstanding local tradition.[23] Rare Killer whales (Orcinus orca) sometimes visit the Faroese fjords as well.

Natural history and biology

A collection of Faroese marine algae resulting from a survey sponsored by NATO, the British Museum (Natural History) and the Carlsberg Foundation, is preserved in the Ulster Museum (catalogue numbers: F3195—F3307). It is one of ten exsiccatae sets.

See also

|

|

References

- ↑ [1] (Faroese)

- ↑ http://www.randburg.com/fa/general/general_5.html

- ↑ http://www.tinganes.fo/Default.aspx?ID=2419

- ↑ Implementation of Schengen convention by the prime minister as approved by the Løgting

- ↑ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/fo.html

- ↑ Brittle tectonism in relation to the Palaeogene evolution of the Thulean/NE Atlantic domain: a study in Ulster Retrieved on 2007-11-10

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Statistics Faroe Islands; Labour Market and Wages Retrieved on 4 August 2009

- ↑ "folkaflokkurin.fo". folkaflokkurin.fo. http://folkaflokkurin.fo/xa.asp?fnk=grn&bnr=1&unr=3&gnr=329. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

- ↑ Lyall, Sarah (2008-11-01). "Iceland, Mired in Debt, Blames Britain for Woes". New York Times. pp. A6. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/02/world/europe/02iceland.html?pagewanted=1. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ↑ http://www.logting.fo/files/casestate/9193/011.09%20Evra-gjaldoyra%20(1).pdf

- ↑ Highly discrepant proportions of female and male Scandinavian and British Isles ancestry within the isolated population of the Faroe Islands, http://www.nature.com/ejhg/journal/v14/n4/full/5201578a.html, Thomas D Als, Tove H Jorgensen, Anders D Børglum, Peter A Petersen, Ole Mors and August G Wang, 25 January 2006

- ↑ The origin of the isolated population of the Faroe Islands investigated using Y chromosomal markers, http://www.springerlink.com/content/4yuhf5m7a22gc4qm/, Tove H. Jorgensen, Henriette N. Buttenschön, August G. Wang, Thomas D. Als, Anders D. Børglum and Henrik Ewald1, 8 April 2004.

- ↑ Wang, C. August. 2006. Ílegur og Føroya Søga. In: Frøði pp.20-23

- ↑ Statistical Facts about the Faroe Islands, http://www.tinganes.fo/Default.aspx?ID=219, The Prime Minister's Office. Retrieved 4 August 2009.

- ↑ Schei, Kjørsvik Liv and Moberg, Gunnie. 1991. The Faroe Islands. ISBN 0-7195-5009-2

- ↑ Brakes, Philippa (2004). "A background to whaling". In Philippa Brakes, Andrew Butterworth, Mark Simmonds & Philip Lymbery. Troubled Waters: A Review of the Welfare Implications of Modern Whaling Activities. p. 7. ISBN 0-9547065-0-1. http://www.wdcs.org/submissions_bin/troubledwaters.pdf.

- ↑ [http://www.whaling.fo/thepilot.htm#Drivingthewhales "Whales and whaling in the Faroe Islands"]. Faroese Government. http://www.whaling.fo/thepilot.htm#Drivingthewhales. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

- ↑ [http://www.wdcs.org/dan/publishing.nsf/allweb/99E632F7502FCC3B802568F20048794C "Why do whales and dolphins strand?"]. WDCS. http://www.wdcs.org/dan/publishing.nsf/allweb/99E632F7502FCC3B802568F20048794C. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

- ↑ Chrismar, Nicole (28 July 2006). "Dolphins Hunted for Sport and Fertilizer". ABC News. http://abcnews.go.com/Technology/story?id=2248161&page=1. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- ↑ GHCN Climate data, Thorshavn series 1881 to 2007

- ↑ [2] The Faroese Fauna.

- ↑ Ryder, M L, (1981), "A survey of European primitive breeds of sheep", Ann. Génét. Sél. Anim., 13 (4), p 400.

- ↑ http://earthfirst.com/pilot-whales-brutally-slaughtered-annually-in-the-faroe-islands/

Literature

- Irvine, D.E.G. 1982. Seaweeds of the Faroes 1: The flora. Bull. Br. Mus. nat. Hist. (Bot.) 10: 109 - 131.

- Tittley, I., Farnham, W.F. and Gray, P.W.G. 1982. Seaweeds of the Faroes 2: Sheltered fjords and sounds. Bull. Br. Mus. nat. Hist. (Bot.) 10: 133 - 151.

- Irvine, David Edward Guthrie. 1982. Seaweed of the Faroes 1: The flora. Bull. Br. Mus. nat. Hist. (Bot.) 10(3): 109 - 131.

External links

- Government

- Prime Minister's Office - Official site

- National Library of the Faroe Islands

- General information

- Faroe Islands entry at The World Factbook

- Faroe Islands at UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Faroe Islands at the Open Directory Project

- Wikimedia Atlas of the Faroe Islands

- Tourism

- Faroe Islands travel guide from Wikitravel

- Visit Faroe Islands official tourist site

- Faroe Islands Tourist Guide

- Gallery of stunning photos of the Faroe Islands

- Faroeislands.dk - Is a private page covering all villages on the Faroe Islands

- Nordic House - Official site of the Nordic House in the Faroe Islands

- New York Times Travel section feature, March 2007

- Photographs of the Faroe Islands

- Other

- vifanord – a digital library that provides scientific information on the Nordic and Baltic countries as well as the Baltic region as a whole

- Faroe Foraminifera – Deep Sea Fauna: Foraminifera of the Faroe shelf and Faroe-Shetland Channel - an image gallery and description of 56 specimens

- GrindaDrap: Video of a Whale Hunt YouTube

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||