Extinction

| Conservation status |

|---|

| by risk of extinction |

| Extinct |

| Extinct Extinct in the Wild |

| Threatened |

| Critically Endangered Endangered Vulnerable |

| At lower risk |

| Conservation Dependent Near Threatened Least Concern |

|

See also IUCN Red List International Union for Conservation of Nature |

In biology and ecology, extinction is the end of an organism or group of taxa. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of that species (although the capacity to breed and recover may have been lost before this point). Because a species' potential range may be very large, determining this moment is difficult, and is usually done retrospectively. This difficulty leads to phenomena such as Lazarus taxa, where a species presumed extinct abruptly "re-appears" (typically in the fossil record) after a period of apparent absence.

Through evolution, new species arise through the process of speciation—where new varieties of organisms arise and thrive when they are able to find and exploit an ecological niche—and species become extinct when they are no longer able to survive in changing conditions or against superior competition. A typical species becomes extinct within 10 million years of its first appearance,[2] although some species, called living fossils, survive virtually unchanged for hundreds of millions of years. Extinction, though, is usually a natural phenomenon; it is estimated that 99.9% of all species that have ever lived are now extinct.[2][3]

Mass extinctions are relatively rare events; however, isolated extinctions are quite common. Only recently have extinctions been recorded and scientists have become alarmed at the high rates of recent extinctions.[4] It is estimated most species that go extinct have never been documented by scientists. Some scientists estimate that up to half of presently existing species may become extinct by 2100.[5]

Contents |

Definition

A species becomes extinct when the last existing member of that species dies. Extinction therefore becomes a certainty when there are no surviving individuals that are able to reproduce and create a new generation. A species may become functionally extinct when only a handful of individuals survive, which are unable to reproduce due to poor health, age, sparse distribution over a large range, a lack of individuals of both sexes (in sexually reproducing species), or other reasons.

Pinpointing the extinction (or pseudoextinction) of a species requires a clear definition of that species. If it is to be declared extinct, the species in question must be uniquely identifiable from any ancestor or daughter species, or from other closely related species. Extinction of a species (or replacement by a daughter species) plays a key role in the punctuated equilibrium hypothesis of Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge.[7]

In ecology, extinction is often used informally to refer to local extinction, in which a species ceases to exist in the chosen area of study, but still exists elsewhere. This phenomenon is also known as extirpation. Local extinctions may be followed by a replacement of the species taken from other locations; wolf reintroduction is an example of this. Species which are not extinct are termed extant. Those that are extant but threatened by extinction are referred to as threatened or endangered species.

An important aspect of extinction at the present time are human attempts to preserve critically endangered species, which is reflected by the creation of the conservation status "Extinct in the Wild" (EW). Species listed under this status by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) are not known to have any living specimens in the wild, and are maintained only in zoos or other artificial environments. Some of these species are functionally extinct, as they are no longer part of their natural habitat and it is unlikely the species will ever be restored to the wild.[8] When possible, modern zoological institutions attempt to maintain a viable population for species preservation and possible future reintroduction to the wild through use of carefully planned breeding programs.

The extinction of one species' wild population can have knock-on effects, causing further extinctions. These are also called "chains of extinction".[9] This is especially common with extinction of keystone species.

Pseudoextinction

Descendants may or may not exist for extinct species. Daughter species that evolve from a parent species carry on most of the parent species' genetic information, and even though the parent species may become extinct, the daughter species lives on. In other cases, species have produced no new variants, or none that are able to survive the parent species' extinction. Extinction of a parent species where daughter species or subspecies are still alive is also called pseudoextinction.

Pseudoextinction is difficult to demonstrate unless one has a strong chain of evidence linking a living species to members of a pre-existing species. For example, it is sometimes claimed that the extinct Hyracotherium, which was an early horse that shares a common ancestor with the modern horse, is pseudoextinct, rather than extinct, because there are several extant species of Equus, including zebra and donkeys. However, as fossil species typically leave no genetic material behind, it is not possible to say whether Hyracotherium actually evolved into more modern horse species or simply evolved from a common ancestor with modern horses. Pseudoextinction is much easier to demonstrate for larger taxonomic groups.

Causes

As long as species have been evolving, species have been going extinct. It is estimated that over 99% of all species that ever lived have gone extinct. The average life-span of most species is 10 million years, although this varies widely between taxa. There are a variety of causes that can contribute directly or indirectly to the extinction of a species or group of species. "Just as each species is unique," write Beverly and Stephen Stearns, "so is each extinction... the causes for each are varied—some subtle and complex, others obvious and simple".[10] Most simply, any species that is unable to survive or reproduce in its environment, and unable to move to a new environment where it can do so, dies out and becomes extinct. Extinction of a species may come suddenly when an otherwise healthy species is wiped out completely, as when toxic pollution renders its entire habitat unliveable; or may occur gradually over thousands or millions of years, such as when a species gradually loses out in competition for food to better adapted competitors.

Assessing the relative importance of genetic factors compared to environmental ones as the causes of extinction has been compared to the nature-nurture debate.[3] The question of whether more extinctions in the fossil record have been caused by evolution or by catastrophe is a subject of discussion; Mark Newman, the author of Modeling Extinction argues for a mathematical model that falls between the two positions.[2] By contrast, conservation biology uses the extinction vortex model to classify extinctions by cause. When concerns about human extinction have been raised, for example in Sir Martin Rees' 2003 book Our Final Hour, those concerns lie with the effects of climate change or technological disaster.

Currently, environmental groups and some governments are concerned with the extinction of species caused by humanity, and are attempting to combat further extinctions through a variety of conservation programs.[4] Humans can cause extinction of a species through overharvesting, pollution, habitat destruction, introduction of new predators and food competitors, overhunting, and other influences. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), 784 extinctions have been recorded since the year 1500 (to the year 2004), the arbitrary date selected to define "modern" extinctions, with many more likely to have gone unnoticed (several species have also been listed as extinct since the 2004 date).[11]

Genetics and demographic phenomena

Population genetics and demographic phenomena affect the evolution, and therefore the risk of extinction, of species. Limited geographic range is the most important determinant of genus extinction at background rates but becomes increasingly irrelevant as mass extinction arises.[12]

Natural selection acts to propagate beneficial genetic traits and eliminate weaknesses. It is nevertheless possible for a deleterious mutation to be spread throughout a population through the effect of genetic drift.

A diverse or deep gene pool gives a population a higher chance of surviving an adverse change in conditions. Effects that cause or reward a loss in genetic diversity can increase the chances of extinction of a species. Population bottlenecks can dramatically reduce genetic diversity by severely limiting the number of reproducing individuals and make inbreeding more frequent. The founder effect can cause rapid, individual-based speciation and is the most dramatic example of a population bottleneck.

Genetic pollution

Purebred wild species evolved to a specific ecology can be threatened with extinction[13] through the process of genetic pollution—i.e., uncontrolled hybridization, introgression genetic swamping which leads to homogenization or out-competition from the introduced (or hybrid) species.[14] Endemic populations can face such extinctions when new populations are imported or selectively bred by people, or when habitat modification brings previously isolated species into contact. Extinction is likeliest for rare species coming into contact with more abundant ones;[15] interbreeding can swamp the rarer gene pool and create hybrids, depleting the purebred gene pool (for example, the endangered Wild water buffalo is most threatened with extinction by genetic pollution from the abundant domestic water buffalo). Such extinctions are not always apparent from morphological (non-genetic) observations. Some degree of gene flow is a normal evolutionarily process, nevertheless, hybridization (with or without introgression) threatens rare species' existence.[16][17]

The gene pool of a species or a population is the variety of genetic information in its living members. A large gene pool (extensive genetic diversity) is associated with robust populations that can survive bouts of intense selection. Meanwhile, low genetic diversity (see inbreeding and population bottlenecks) reduces the range of adaptions possible.[18] Replacing native with alien genes narrows genetic diversity within the original population,[19][15] thereby increasing the chance of extinction.

Habitat degradation

Habitat degradation is currently the main anthropogenic cause of species extinctions. The main cause of habitat degradation worldwide is agriculture, with urban sprawl, logging, mining and some fishing practices close behind. The degradation of a species' habitat may alter the fitness landscape to such an extent that the species is no longer able to survive and becomes extinct. This may occur by direct effects, such as the environment becoming toxic, or indirectly, by limiting a species' ability to compete effectively for diminished resources or against new competitor species.

Habitat degradation through toxicity can kill off a species very rapidly, by killing all living members through contamination or sterilizing them. It can also occur over longer periods at lower toxicity levels by affecting life span, reproductive capacity, or competitiveness.

Habitat degradation can also take the form of a physical destruction of niche habitats. The widespread destruction of tropical rainforests and replacement with open pastureland is widely cited as an example of this;[5] elimination of the dense forest eliminated the infrastructure needed by many species to survive. For example, a fern that depends on dense shade for protection from direct sunlight can no longer survive without forest to shelter it. Another example is the destruction of ocean floors by bottom trawling.[20]

Diminished resources or introduction of new competitor species also often accompany habitat degradation. Global warming has allowed some species to expand their range, bringing unwelcome competition to other species that previously occupied that area. Sometimes these new competitors are predators and directly affect prey species, while at other times they may merely outcompete vulnerable species for limited resources. Vital resources including water and food can also be limited during habitat degradation, leading to extinction.

Predation, competition, and disease

Before the evolution of hominids, life forms competed with each other and drove one another extinct. Recently in geologic time, Humans have been transporting animals and plants from one part of the world to another for thousands of years, sometimes deliberately (e.g., livestock released by sailors onto islands as a source of food) and sometimes accidentally (e.g., rats escaping from boats). In most cases, such introductions are unsuccessful, but when they do become established as an invasive alien species, the consequences can be catastrophic. Invasive alien species can affect native species directly by eating them, competing with them, and introducing pathogens or parasites that sicken or kill them or, indirectly, by destroying or degrading their habitat. Human populations may themselves act as invasive predators. According to the "overkill hypothesis", the swift extinction of the megafauna in areas such as New Zealand, Australia, Madagascar and Hawaii resulted from the sudden introduction of human beings to environments full of animals that had never seen them before, and were therefore completely unadapted to their predation techniques.[21]

Coextinction

Coextinction refers to the loss of a species due to the extinction of another; for example, the extinction of parasitic insects following the loss of their hosts. Coextinction can also occur when a species loses its pollinator, or to predators in a food chain who lose their prey. "Species coextinction is a manifestation of the interconnectedness of organisms in complex ecosystems ... While coextinction may not be the most important cause of species extinctions, it is certainly an insidious one".[22] Coextinction is especially common when a keystone species goes extinct.

Global warming

A 2003 review across 14 biodiversity research centers predicted that, because of climate change, 15–37% of land species would be "committed to extinction" by 2050.[23][24][25] The ecologically rich areas that would potentially suffer the heaviest losses include the Cape Floristic Region, and the Caribbean Basin. These areas might see a doubling of present carbon dioxide levels and rising temperatures that could eliminate 56,000 plant and 3,700 animal species.[26]

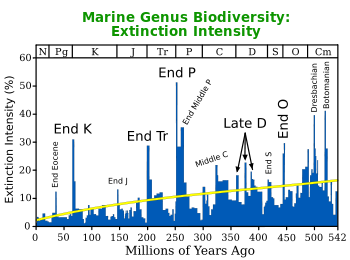

Mass extinctions

There have been at least five mass extinctions in the history of life on earth, and four in the last 3.5 billion years in which many species have disappeared in a relatively short period of geological time. The most recent of these, the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event 65 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous period, is best known for having wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs, among many other species.

Modern extinctions

According to a 1998 survey of 400 biologists conducted by New York's American Museum of Natural History, nearly 70 percent believed that they were currently in the early stages of a human-caused extinction,[27] known as the Holocene extinction. In that survey, the same proportion of respondents agreed with the prediction that up to 20 percent of all living populations could become extinct within 30 years (by 2028). Biologist E. O. Wilson estimated [5] in 2002 that if current rates of human destruction of the biosphere continue, one-half of all species of life on earth will be extinct in 100 years.[28] More significantly the rate of species extinctions at present is estimated at 100 to 1000 times "background" or average extinction rates in the evolutionary time scale of planet Earth.[29]

History of scientific understanding

In the 1800s when extinction was first described, the idea of extinction was threatening to those who held a belief in the Great Chain of Being, a theological position that did not allow for "missing links".[30]

The possibility of extinction was not widely accepted before the 1800s.[30][31] The devoted naturalist Carl Linnaeus, could "hardly entertain" the idea that humans could cause the extinction of a species.[32] When parts of the world had not been thoroughly examined and charted, scientists could not rule out that animals found only in the fossil record were not simply "hiding" in unexplored regions of the Earth.[33] Georges Cuvier is credited with establishing extinction as a fact in a 1796 lecture to the French Institute.[31] Cuvier's observations of fossil bones convinced him that they did not originate in extant animals. This discovery was critical for the spread of uniformitarianism,[34] and lead to the first book publicizing the idea of evolution [35] though Cuvier himself strongly opposed the theories of evolution advanced by Lamarck and others.

Human attitudes and interests

Extinction is an important research topic in the field of zoology, and biology in general, and has also become an area of concern outside the scientific community. A number of organizations, such as the Worldwide Fund for Nature, have been created with the goal of preserving species from extinction. Governments have attempted, through enacting laws, to avoid habitat destruction, agricultural over-harvesting, and pollution. While many human-caused extinctions have been accidental, humans have also engaged in the deliberate destruction of some species, such as dangerous viruses, and the total destruction of other problematic species has been suggested. Other species were deliberately driven to extinction, or nearly so, due to poaching or because they were "undesirable", or to push for other human agendas. One example was the near extinction of the American bison, which was nearly wiped out by mass hunts sanctioned by the United States government, in order to force the removal of Native Americans, many of whom relied on the bison for food.

Biologist Bruce Walsh of the University of Arizona states three reasons for scientific interest in the preservation of species; genetic resources, ecosystem stability, and ethics;[36] and today the scientific community "stress[es] the importance" of maintaining biodiversity.[36][37]

In modern times, commercial and industrial interests often have to contend with the effects of production on plant and animal life. However, some technologies with minimal, or no, proven harmful effects on Homo sapiens can be devastating to wildlife (for example, DDT).[38] Biogeographer Jared Diamond notes that while big business may label environmental concerns as "exaggerated", and often cause "devastating damage", some corporations find it in their interest to adopt good conservation practices, and even engage in preservation efforts that surpass those taken by national parks.[39]

Governments sometimes see the loss of native species as a loss to ecotourism,[40] and can enact laws with severe punishment against the trade in native species in an effort to prevent extinction in the wild. Nature preserves are created by governments as a means to provide continuing habitats to species crowded by human expansion. The 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity has resulted in international Biodiversity Action Plan programmes, which attempt to provide comprehensive guidelines for government biodiversity conservation. Advocacy groups, such as The Wildlands Project[41] and the Alliance for Zero Extinctions,[42] work to educate the public and pressure governments into action.

People who live close to nature can be dependent on the survival of all the species in their environment, leaving them highly exposed to extinction risks. However, people prioritize day-to-day survival over species conservation; with human overpopulation in tropical developing countries, there has been enormous pressure on forests due to subsistence agriculture, including slash-and-burn agricultural techniques that can reduce endangered species's habitats.[43]

Libertarians have sometimes expressed skepticism that extinction of species will have significant negative effects. Michael Levin argues, "The very fact that a species is near extinction implies that its final demise will have negligible impact."[44]

Planned extinction

Humans have aggressively worked toward the extinction of many species of viruses and bacteria in the cause of disease eradication. For example, the smallpox virus is now extinct in the wild[45]—although samples are retained in laboratory settings, and the polio virus is now confined to small parts of the world as a result of human efforts to prevent the disease it causes.[46]

Olivia Judson is one of six modern scientists to have advocated the deliberate extinction of specific species. Her September 25, 2003 New York Times article, "A Bug's Death", advocates "specicide" of thirty mosquito species through the introduction of a genetic element, capable of inserting itself into another crucial gene, to create recessive "knockout genes". Her arguments for doing so are that the Anopheles mosquitoes (which spread malaria) and Aedes mosquitoes (which spread dengue fever, yellow fever, elephantiasis, and other diseases) represent only 30 species; eradicating these would save at least one million human lives per annum at a cost of reducing the genetic diversity of the family Culicidae by only 1%. She further argues that since species become extinct "all the time" the disappearance of a few more will not destroy the ecosystem: "We're not left with a wasteland every time a species vanishes. Removing one species sometimes causes shifts in the populations of other species — but different need not mean worse." In addition, anti-malarial and mosquito control programs offer little realistic hope to the 300 million people in developing nations who will be infected with acute illnesses this year. Although trials are ongoing, she writes that if they fail: "We should consider the ultimate swatting."[47]

Cloning

Ongoing technological advances have encouraged the hypothesis that by using DNA from the remains of an extinct species, through the process of cloning, the species may be "brought back to life". Proposed targets for cloning include the dinosaurs, the mammoth, thylacine, and the Pyrenean Ibex. In order for such a program to succeed, a sufficient number of individuals would have to be cloned, from the DNA of different individuals (in the case of sexually reproducing organisms) to create a viable population. Though bioethical and philosophical objections have been raised,[48] the cloning of extinct creatures seems a viable outcome of the continuing advancements in our science and technology.[49]

In 2003, scientists attempted to clone the extinct Pyrenean Ibex (C. p. pyrenaica). This initial attempt failed; of the 285 embryos reconstructed, 54 were transferred to 12 mountain goats and mountain goat-domestic goat hybrids, but only two survived the initial two months of gestation before they too died.[50] In 2009, a second attempt was made to clone the Pyrenean Ibex; one clone was born alive, but died seven minutes later, due to physical defects in the lungs.[51]

The concept of cloning extinct species was thought to be first popularized by the successful novel and movie Jurassic Park, though it may have been first used in John Brosnan's 1984 novel Carnosaur, and later in Piers Anthony's Balook novel, which resurrected a Baluchitherium.

See also

- Endling

- Gene pool

- Genetic erosion

- Genetic pollution

- Habitat fragmentation

- IUCN Red List

- IUCN Red List of extinct species for a list by taxonomy

- Ecological importance of bees

- List of extinct animals

- List of extinct plants

- Living Planet Index

- Mass extinction

- Overexploitation

- Red List Index

- Refugium (population biology)

- Speciation

- Timeline of extinctions

- Voluntary Human Extinction Movement

- Dinosaurs

References

- ↑ Diamond, Jared (1999). "Up to the Starting Line". Guns, Germs, and Steel. W. W. Norton. pp. 43–44. ISBN 0-393-31755-2.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Newman, Mark. "A Mathematical Model for Mass Extinction". Cornell University. May 20, 1994. URL accessed July 30, 2006.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Raup, David M. Extinction: Bad Genes or Bad Luck? W.W. Norton and Company. New York. 1991. pp.3-6 ISBN 978-0-393-30927-0

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Species disappearing at an alarming rate, report says. MSNBC URL accessed July 26, 2006

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Wilson, E.O., The Future of Life (2002) (ISBN 0-679-76811-4). See also: Leakey, Richard, The Sixth Extinction : Patterns of Life and the Future of Humankind, ISBN 0-385-46809-1

- ↑ Davis, Paul and Kenrick, Paul. Fossil Plants. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C. (2004). Morran, Robin, C.; A Natural History of Ferns. Timber Press (2004). ISBN 0-88192-667-1

- ↑ See: Niles Eldredge, Time Frames: Rethinking of Darwinian Evolution and the Theory of Punctuated Equilibria, 1986, Heinemann ISBN 0-434-22610-6

- ↑ Maas, Peter. "Extinct in the Wild" The Extinction Website. URL accessed January 26 2007.

- ↑ Quince, C. et al. (pdf). Deleting species from model food webs. http://theory.ph.man.ac.uk/~ajm/qui05a.pdf. Retrieved 2007-02-15.

- ↑ Stearns, Beverly Peterson and Stephen C. (2000). "Preface". Watching, from the Edge of Extinction. Yale University Press. pp. x. ISBN 0300084692.

- ↑ "2004 Red List". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. World Conservation Union. Archived from the original on 12 February 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080212161231/http://www.iucn.org/themes/ssc/red_list_2004/GSAexecsumm_EN.htm. Retrieved September 20, 2006.

- ↑ Payne, J.L. & S. Finnegan (2007). "The effect of geographical range on extinction risk during background and mass extinction.". Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 104 (25): 10506–11. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701257104. PMID 17563357.

- ↑ Mooney, H. A.; Cleland, E. E. (2001). "The evolutionary impact of invasive species". PNAS 98 (10): 5446–5451. doi:10.1073/pnas.091093398. PMID 11344292.

- ↑ Glossary: definitions from the following publication: Aubry, C., R. Shoal and V. Erickson. 2005. Grass cultivars: their origins, development, and use on national forests and grasslands in the Pacific Northwest. USDA Forest Service. 44 pages, plus appendices.; Native Seed Network (NSN), Institute for Applied Ecology, 563 SW Jefferson Ave, Corvallis, OR 97333, USA

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Australia's state of the forests report". 2003. p. 107. http://adl.brs.gov.au/data/warehouse/brsShop/data/12858_10_1_3.pdf.

- ↑ Rhymer, J. M.; Simberloff, D. (November 1996). "Extinction by Hybridization and Introgression". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, (Annual Reviews) 27: 83–109. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.27.1.83. http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.27.1.83. "Introduced species, in turn, are seen as competing with or preying on native species or destroying their habitat. Introduces species (or subspecies), however, can generate another kind of extinction, a genetic extinction by hybridization and introgression with native flora and fauna.".

- ↑ Potts, Brad M. (September 2001). Robert C. Barbour, Andrew B. Hingston. Genetic pollution from farm forestry using eucalypt species and hybrids : a report for the RIRDC/L&WA/FWPRDC Joint Venture Agroforestry Program (Australian Government, Rural Industrial Research and Development Corporation). ISBN 0-642-58336-6.

- ↑ "GENETIC DIVERSITY". 2003. p. 104. http://adl.brs.gov.au/data/warehouse/brsShop/data/12858_10_1_3.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-30. "In other words, greater genetic diversity can offer greater resilience. In order to maintain the capacity of our forests to adapt to future changes, therefore, genetic diversity must be preserved"

- ↑ Lindenmayer, D. B.; Hobbs, R. J.; Salt, D. (2003-01-06). "Plantation forests and biodiversity conservation". Australian Forestry 66 (1): 64. http://www.forestry.org.au/pdf/pdf-members/afj/AFJ%202003%20v66/AFJ%20March%202003%2066-1/12_Lindenmayer.pdf. "there may be genetic invasion from pollen dispersal and subsequent hybridisation between eucalypt tree species used to establish plantations and eucalypts endemic to an area (Potts et al. 2001). This may, in turn, alter natural patterns of genetic variability".

- ↑ Clover, Charles. 2004. The End of the Line: How overfishing is changing the world and what we eat. Ebury Press, London. ISBN 0-09-189780-7

- ↑ Lee, Anita. "The Pleistocene Overkill Hypothesis." University of California at Berkeley Geography Program. URL accessed January 11, 2007.

- ↑ Koh, Lian Pih. Science, Vol 305, Issue 5690, 1632-1634, 10 September 2004.

- ↑ Thomas, C. D.; et al (2004-01-08). "Extinction risk from climate change". Nature (journal) 427 (6970): 145–148. doi:10.1038/nature02121. PMID 14712274. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v427/n6970/abs/nature02121.html. Retrieved 2010-05-28. "minimal climate-warming scenarios produce lower projections of species committed to extinction (approx18%)". (Letter to Nature received 10 September 2003.)

- ↑ Battachatya, Shaoni. [1]." URL accessed September 15, 2008.

- ↑ Bhattacharya, Shaoni (07 January 2004). "Global warming threatens millions of species". New Scientist. http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn4545-global-warming-threatens-millions-of-species.html. Retrieved 2010-05-28. "the effects of climate change should be considered as great a threat to biodiversity as the "Big Three" - habitat destruction, invasions by alien species and overexploitation by humans."

- ↑ Handwerk, Brian, and Brian Hendwerk. "Global Warming Could Cause Mass Extinctions by 2050, Study Says." National Geographic News (Apr. 2006): n. pag. www.nationalgeographic.com. Web. 12 Oct. 2009.

- ↑ American Museum of Natural History. "National Survey Reveals Biodiversity Crisis - Scientific Experts Believe We are in the Midst of the Fastest Mass Extinction in Earth's History". URL accessed September 20, 2006.

- ↑ Ulansey, David, "The current mass extinction" repeats this statement with links to dozens of news reports on the phenomenon. URL accessed January 26, 2007.

- ↑ J.H.Lawton and R.M.May, Extinction rates, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Viney, Mike. "Extinction Part 2 of 5". Colorado State University. URL accessed September 12, 2006.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Academy of Natural Sciences, "Fossils and Extinction" (http://www.ansp.org/museum/jefferson/otherPages/extinction.php) and U.C. Berkeley "History of Evolutionary Thought — Extinction" http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evosite/history/extinction.shtml.

- ↑ Koerner, Lisbet (1999). "God's Endless Larder". Linnaeus: Nature and Nation. Harvard University Press. pp. 85. ISBN 0-674-00565-1.

- ↑ Ideas: A History from Fire to Freud (Peter Watson Weidenfeld & Nicolson ISBN 0-297-60726-X)

- ↑ Watson, p.16

- ↑ Robert Chambers, 1844, Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, 1994 reprint: University of Chicago Press ISBN 0-226-10073-1

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Walsh, Bruce. Extinction. Bioscience at University of Arizona. URL accessed July 26, 2006.

- ↑ Committee on Recently Extinct Organisms. "Why Care About Species That Have Gone Extinct?". URL accessed July 30, 2006.

- ↑ International Programme on Chemical Safety (1989). "DDT and its Derivatives -- Environmental Aspects". Environmental Health Criteria 83. URL accessed September 20, 2006.

- ↑ Diamond, Jared (2005). "A Tale of Two Farms". Collapse. Penguin. pp. 15–17. ISBN 0-670-03337-5.

- ↑ Drewry, Rachel. "Ecotourism: Can it save the orangutans?" Inside Indonesia. URL accessed January 26, 2007.

- ↑ The Wildlands Project. URL accessed January 26, 2007.

- ↑ Alliance for Zero Extinctions. URL accessed January 26, 2007.

- ↑ Ehrlich, Anne (1981). Extinction: The Causes and Consequences of the Disappearance of Species. Random House, New York. ISBN 0-394-51312-6.

- ↑ Levin, Michael (November 1997), Animals and the Market, 15, The Free Market, http://mises.org/freemarket_detail.aspx?control=111

- ↑ WHO Factsheet WHO meeting agenda Scientists certified it eradicated in December 1979, WHO formally ratified this on 8 May 1980 in resolution WHA33.3

- ↑ Global Polio Eradication Initiative. "The History". URL accessed January 24, 2007.

- ↑ Judson, Olivia (September 25, 2003). ""A Bug's Death"". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?sec=health&res=9805E5DF143DF936A1575AC0A9659C8B63&n=Top%2fNews%2fScience%2fTopics%2fMosquitoes. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- ↑ A. Zitner (2000-12-24). "Cloned Goat Would Revive Extinct Line". Los Angeles Times. http://articles.latimes.com/2000/dec/24/news/mn-4250/2. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ↑ NICHOLAS WADE (2008-11-19). "Regenerating a Mammoth for $10 Million". http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/20/science/20mammoth.html?_r=1. Retrieved 2010-05-17. The cell could be converted into an embryo and brought to term by an elephant, a project he estimated would cost some $10 million. “This is something that could work, though it will be tedious and expensive,”

- ↑ Steve Connor (2009-02-02). "Cloned goat dies after attempt to bring species back from extinction". The Independent. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/cloned-goat-dies-after-attempt-to-bring-species-back-from-extinction-1522974.html. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ↑ Extinct ibex is resurrected by cloning

External links

- Committee on recently extinct organisms

- Recently Extinct Animals

- H.E. Strickland's The Dodo and its Kindred (London: 1848), a study of three extinct bird species — full digital facsimile, Linda Hall Library

- Sepkoski's Global Genus Database of Marine Animals — Calculate past mass extinction rates for yourself!

|

||||||||||||||||||||