Expressionism

'Expressionism' was a cultural movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Germany at the start of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world under an utterly subjective perspective, violently distorting it to obtain an emotional effect and vividly transmit personal moods and ideas.[1][2] Expressionist artists sought to express the meaning of "being alive"[3] and emotional experience rather than physical reality.[3][4]

Expressionism emerged as an 'avant-garde movement' in poetry and painting before the First World War; in the Weimar years was being appreciated by a mass audience,[1] having its popularity peak in Berlin, during the 1920s.

Expressionism is exhibited in many art forms, including: painting, literature, theatre, dance, film, architecture and music. The term often implies emotional angst. In a general sense, painters such as Matthias Grünewald and El Greco can be called expressionist, though in practice, the term is applied mainly to 20th century works.

The Expressionist stress on the individual perspective was also a reaction to positivism and other artistic movements such as naturalism and impressionism.[5]

Contents |

Origin of the term

Although it is used as a term of reference, there has never been a distinct movement that called itself "expressionism", apart from the use of the term by Herwarth Walden in his polemic magazine Der Sturm in 1912. The term is usually linked to paintings and graphic work in Germany at the turn of the century which challenged the academic traditions, particularly through the Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter groups. Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche played a key role in originating modern expressionism by clarifying and serving as a conduit for previously neglected currents in ancient art.

In The Birth of Tragedy Nietzsche presented his theory of the ancient dualism between two types of aesthetic experience, namely the Apollonian and the Dionysian; a dualism between the plastic "art of sculpture", of lyrical dream-inspiration, identity (the principium individuationis), order, regularity, and calm repose, and, on the other hand, the non-plastic "art of music", of intoxication, forgetfulness, chaos, and the ecstatic dissolution of identity in the collective. The analogy with the world of the Greek gods typifies the relationship between these extremes: two godsons, incompatible and yet inseparable. According to Nietzsche, both elements are present in any work of art. The basic characteristics of expressionism are Dionysian: bold colours, distorted forms-in-dissolution, two-dimensional, without perspective.[6]

More generally the term refers to art that expresses intense emotion. It is arguable that all artists are expressive but there is a long line of art production in which heavy emphasis is placed on communication through emotion. Such art often occurs during time of social upheaval, and through the tradition of graphic art there is a powerful and moving record of chaos in Europe from the 15th century on the Protestant Reformation, German Peasants' War, Eight Years' War, Spanish Occupation of the Netherlands, the rape, pillage and disaster associated with countless periods of chaos and oppression are presented in the documents of the printmaker. Often the work is unimpressive aesthetically, but almost without exception has the capacity to move the viewer to strong emotions with the drama and often horror of the scenes depicted.

The term was also coined by Czech art historian Antonín Matějček in 1910 as the opposite of impressionism: "An Expressionist wishes, above all, to express himself... (an Expressionist rejects) immediate perception and builds on more complex psychic structures... Impressions and mental images that pass through mental peoples soul as through a filter which rids them of all substantial accretions to produce their clear essence [...and] are assimilated and condense into more general forms, into types, which he transcribes through simple short-hand formulae and symbols." (Gordon, 1987)

Visual artists

Some of the movement's leading visual artists in the early 20th century were:

- Australia: Sidney Nolan, Charles Blackman, John Perceval, Albert Tucker and Joy Hester

- Austria: Egon Schiele, Oskar Kokoschka and Alfred Kubin

- Belgium: Constant Permeke, Gustave De Smet, Frits Van den Berghe, James Ensor, Albert Servaes, Floris Jespers and Albert Droesbeke.

- Brazil: Anita Malfatti, Cândido Portinari, Di Cavalcanti and Lasar Segall.

- Estonia:Nikolai Triik, Konrad Mägi, Aleksander Tassa, Anton Starkopf, Ado Vabbe, Eduard Wiiralt,

- Finland: Tyko Sallinen, Alvar Cawén, Juho Mäkelä and Wäinö Aaltonen.

- France: Georges Rouault, Georges Gimel, Gen Paul and Chaim Soutine

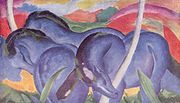

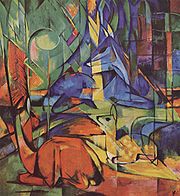

- Germany: Ernst Barlach, Max Beckmann, Fritz Bleyl, Heinrich Campendonk, Otto Dix, Conrad Felixmüller, George Grosz, Erich Heckel, Carl Hofer, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paul Klee, Käthe Kollwitz, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler, August Macke, Franz Marc, Ludwig Meidner, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Otto Mueller, Gabriele Münter, Rolf Nesch, Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff.

- Hungary: Tivadar Kosztka Csontváry

- Iceland: Einar Hákonarson

- Indonesia: Affandi

- Italy: Emilio Giuseppe Dossena

- Lithuania: Mstislav Dobuzhinsky.

- Mexico: Mathias Goeritz (German émigré to Mexico), Rufino Tamayo

- Netherlands: Charles Eyck, Willem Hofhuizen, Jaap Min, Jan Sluyters, Vincent van Gogh, Jan Wiegers and Hendrik Werkman

- Norway: Edvard Munch, Kai Fjell

- Poland: Henryk Gotlib

- Portugal: Mário Eloy

- Russia: Wassily Kandinsky, Marc Chagall, Alexej von Jawlensky and Natalia Goncharova and Marianne von Werefkin (Russian-born, later active in Switzerland).

- Switzerland: Carl Eugen Keel, Cuno Amiet

- USA: Ivan Albright, Milton Avery, George Biddle, Hyman Bloom, Peter Blume, Charles Burchfield, Stuart Davis, Elaine de Kooning, Willem de Kooning, Beauford Delaney, Arthur G. Dove, Norris Embry, Philip Evergood, William Gropper, Philip Guston, Marsden Hartley, Albert Kotin, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Rico Lebrun, Jack Levine, Alfred Henry Maurer, Alice Neel, Abraham Rattner, Ben Shahn, Harry Shoulberg, Joseph Stella, Harry Sternberg, Henry Ossawa Tanner, Dorothea Tanning, Max Weber, Hale Woodruff and Karl Zerbe

Expressionist groups in painting

The movement primarily originated in Germany and Austria. There were a number of Expressionist groups in painting, including Der Blaue Reiter and Die Brücke. The Der Blaue Reiter group was based in Munich and Die Brücke was based originally in Dresden (although some later moved to Berlin). Die Brücke was active for a longer period than Der Blaue Reiter which was only truly together for a year (1912). The Expressionists had many influences, among them Munch, Vincent van Gogh, and African art. They also came to know the work being done by the Fauves in Paris.

Influenced by the Fauves, Expressionism worked with arbitrary colors as well as jarring compositions. In reaction and opposition to French Impressionism which focused on rendering the sheer visual appearance of objects, Expressionist artists sought to capture emotions and subjective interpretations: It was not important to reproduce an aesthetically pleasing impression of the artistic subject matter; the Expressionists focused on capturing vivid emotional reactions through powerful colors and dynamic compositions instead. The leader of Der Blaue Reiter, Kandinsky, would take this a step further. He believed that with simple colors and shapes the spectator could perceive the moods and feelings in the paintings, therefore he made the move to abstraction.

- Expressionist imagery exploded into modern art from the subconscious. Its divers formal means and emotional effects range from anguish to exuberance. As the powerful, personal creations of modern individuals, these images have little in common except their inventive power and their reliance upon a distinctly private vision.

The ideas of German expressionism influenced the work of American artist Marsden Hartley, who met Kandinsky in Germany in 1913.[7] In late 1939, at the beginning of World War II, New York welcomed a great number of leading European artists.

- The heritage of their interest in the mythic realm of the unconscious would be continued—and extended—by another group of younger, New World artists—New York School. [8]

Following World War II Expressionism influenced many young American artists. Norris Embry (1921-1981) studied with Oskar Kokoschka in 1947 and over the next 43 years produced a large body of work grounded in the Expressionist tradition. Norris Embry has been called "the first American German Expressionist". Other American artists of the late 20th and early 21st century have developed distinct movements that are generally considered part of Expressionism. Another prominent artist who came from the German Expressionist "school" was Bremen born Wolfgang Degenhardt. After working as a commercial artist in Bremen he migrated to Australia in 1954 and became quite prominent and sought after in the Hunter Valley region. His paintings captured the spirit of Australian and world issues but presented them in a way which was true to his German Expressionist roots.

American Expressionism[9] and American Figurative Expressionism particularly the Boston figurative expressionism[10] were an integral part of American modernism around the Second World War.

Major figurative Boston expressionists included: Karl Zerbe, Hyman Bloom, Jack Levine, David Aronson, Philip Guston. The Boston figurative expressionists post World War II were increasingly marginalized by the development of abstract expressionism centered in New York City.

After World War II, figurative expressionism influenced worldwide a large number of artists and movements. Thomas B. Hess,[11] wrote:

- “the ‘New figurative painting’ which some have been expecting as a reaction against Abstract Expressionism was implicit in it at the start, and is one of its most lineal continuities.”

- New York Figurative Expressionism[12][13] of the fifties represented New York figurative artists such as: Robert Beauchamp, Elaine de Kooning, Robert Goodnough, Grace Hartigan, Lester Johnson, Alex Katz, George McNeil, Jan Muller, Fairfield Porter, Gregorio Prestopino, Larry Rivers and Bob Thompson.

- Lyrical Abstraction, Tachisme[14] of the 1940s and 1950s in Europe represented by artists such as Georges Mathieu, Hans Hartung, Nicolas de Staël and others.

- Bay Area Figurative Movement[15][16] represented by the early figurative expressionists from the San Francisco area Elmer Bischoff Richard Diebenkorn, and David Park. The movement from 1950-1965 was joined by Theophilus Brown, Paul Wonner, James Weeks, Hassel Smith, Nathan Oliveira, Bruce McGaw, Joan Brown, Manuel Neri, Joan Savo and Roland Peterson.

- Abstract Expressionism, of the 1950s represented American artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Hans Burkhardt, Mary Callery, Nicolas Carone, Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, and others [17][18] that took part in figurative expressionism.

- In the United States and Canada Lyrical Abstraction beginning in the late 1960s and the 1970s. Characterized by the work of Dan Christensen, Peter Young, Ronnie Landfield, Ronald Davis, Larry Poons, Walter Darby Bannard, Charles Arnoldi, Pat Lipsky and many others.[19][20][21]

- Neo-expressionism was an international revival movement beginning in the late 1970s and centered around artists across the world:

- Germany: Anselm Kiefer and Georg Baselitz and others;

- USA: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Eric Fischl, David Salle and Julian Schnabel;

- Cuba: Pablo Carreno;

- France: Rémi Blanchard, Hervé Di Rosa and others;

- Italy: Francesco Clemente, Sandro Chia and Enzo Cucchi;

- England: David Hockney, Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff

- Belarus: Natalia Chernogolova

Selected Expressionist paintings

Franz Marc, Fighting Forms, 1914. |

Egon Schiele, Pair of Women (Women embracing each other), 1915. |

Amedeo Modigliani, Diego Rivera, 1914. |

In other arts

Expressionism is also used to describe styles in other art forms.

Dance

See Expressionist dance. Exponents of expressionist dance included Mary Wigman, Rudolf von Laban, and Pina Bausch.

Sculpture

Some sculptors also adopted this style, as for example Ernst Barlach. Other expressionist artists mainly known as painters, such as Erich Heckel, also worked in sculptural media.

Film

There was also an expressionist movement in film, often referred to as German Expressionism. The most important examples are Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), The Golem: How He Came Into the World (1920), Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927) and F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu, a Symphony of Horror (1922). The term "expressionism" is also sometimes used to refer to stylistic devices that either resemble or draw inspiration from the German Expressionism movement, such as in Film Noir cinematography or in several of the films of Ingmar Bergman. More generally, expressionism can be used to describe to film styles of heightened artifice, such as the technicolor melodramas of Douglas Sirk or the striking sound and visual design in David Lynch's films.

Literature

In literature the novels of Franz Kafka are often described as expressionist. Expressionist poetry also flourished mainly in the German-speaking countries. The most influential expressionist poets were Georg Trakl, Georg Heym, Ernst Stadler, Gottfried Benn and August Stramm.

Theatre

In the theatre, there was a concentrated Expressionist movement in early 20th century German theatre of which Georg Kaiser and Ernst Toller were the most famous playwrights. Other notable expressionist dramatists included Reinhard Sorge, Walter Hasenclever, Hans Henny Jahnn, and Arnolt Bronnen. They looked back to Swedish playwright August Strindberg and German actor and dramatist Frank Wedekind as precursors of their dramaturgical experiments.

Oskar Kokoschka's 1909 playlet, Murderer, The Hope of Women is often called the first expressionist drama. In it, an unnamed man and woman struggle for dominance. The Man brands the woman; she stabs and imprisons him. He frees himself and she falls dead at his touch. As the play ends, he slaughters all around him (in the words of the text) "like mosquitoes." The extreme simplification of characters to mythic types, choral effects, declamatory dialogue and heightened intensity all would become characteristic of later expressionist plays. It is noteworthy that the young Paul Hindemith created an operatic version of this play, to shocking effect in the music world.

Expressionist plays often dramatize the spiritual awakening and sufferings of their protagonists, and are referred to as Stationendramen (station plays), modeled on the episodic presentation of the suffering and death of Jesus in the Stations of the Cross. August Strindberg had pioneered this form with his autobiographical trilogy To Damascus.

The plays often dramatize the struggle against bourgeois values and established authority, often personified in the figure of the Father. In Sorge's The Beggar, (Der Bettler), the young hero's mentally ill father raves about the prospect of mining the riches of Mars; he is finally poisoned by his son. In Bronnen's Parricide (Vatermord), the son stabs his tyranncial father to death, only to have to fend off the frenzied sexual overtures of his mother.

In expressionist drama, the speech is heightened, whether expansive and rhapsodic, or clipped and telegraphic. Director Leopold Jessner became famous for his expressionistic productions, often unfolding on the stark, steeply raked flights of stairs that quickly became his trademark. In the 1920s, expressionism enjoyed a brief period of popularity in the American theatre, including plays by Eugene O'Neill (The Hairy Ape, The Emperor Jones and The Great God Brown), Sophie Treadwell (Machinal) and Elmer Rice (The Adding Machine).

Music

In music, Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern and Alban Berg, the members of the Second Viennese School, wrote pieces described as expressionist (Schoenberg also made expressionist paintings). Other composers who followed them, such as Ernst Krenek, are often considered as a part of the expressionist movement in music. What distinguished these composers from their contemporaries such as Maurice Ravel, George Gershwin and Igor Stravinsky is that expressionist composers self-consciously used atonality to free their artform from the traditional tonality. They also sought to express the subconscious, the 'inner necessity' and suffering through their highly dissonant musical language. Erwartung and Die Glückliche Hand, by Schoenberg, and Wozzeck, an opera by Alban Berg (based on the play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner), are examples of expressionist works.

Architecture

In architecture, two specific buildings are identified as expressionist: Bruno Taut's Glass Pavilion at the Cologne Werkbund Exhibition (1914), and Erich Mendelsohn's Einstein Tower in Potsdam, Germany completed in 1921. Hans Poelzig's Berlin theatre (Grosse Schauspielhaus) interior for Max Reinhardt is also sometimes cited. The influential architectural critic and historian, Sigfried Giedion in his book Space, Time and Architecture (1941) dismissed Expressionist architecture as a side show in the development of functionalism. In Mexico, in 1953, German émigré Mathias Goeritz, published the "Arquitectura Emocional" (Emotional architecture) manifesto where he declared that "architecture's principal function is emotion." [22] Modern Mexican architect Luis Barragán adopted the term that influenced his work. The two of them collaborated in the project Torres de Satélite (1957-58) guided by Goeritz's principles of Arquitectura Emocional. It was only in the 1970s that expressionism in architecture came to be re-evaluated in a more positive light.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bruce Thompson, University of California, Santa Cruz, lecture on WEIMAR CULTURE/KAFKA'S PRAGUE

- ↑ Chris Baldick Concise Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms, entry for Expressionism

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Victorino Tejera, 1966, pages 85,140, Art and Human Intelligence, Vision Press Limited, London

- ↑ The Oxford Illustratd Dictionary, 1976 edition, page 294

- ↑ Garzanti, Aldo (1974) [1972] (in Italian). Enciclopedia Garzanti della letteratura. Milan: Guido Villa. pp. 963. page 241

- ↑ See Nietzsche (1872, sections 1-6).

- ↑ "Hartley, Marsden", Oxford Art Online

- ↑ ‘’Art History’’ (New York, N.Y. : Abbeville Press, ©1993.) ISBN 1558596054 p. 413

- ↑ Bram Dijkstra, American expressionism : art and social change, 1920-1950,(New York : H.N. Abrams, in association with the Columbus Museum of Art, 2003.) ISBN 0810942313 9780810942318

- ↑ Judith Bookbinder, Boston modern: figurative expressionism as alternative modernism (Durham, N.H. : University of New Hampshire Press ; Hanover : University Press of New England, ©2005.) ISBN 1584654880 9781584654889

- ↑ Thomas B. Hess, “The Many Death of American Art,” Art News 59 (October 1960), p.25

- ↑ Paul Schimmel and Judith E Stein, The Figurative fifties : New York figurative expressionism (Newport Beach, California : Newport Harbor Art Museum : New York : Rizzoli, 1988.) ISBN 0847809420 9780847809424 0917493125 9780917493126

- ↑ “Editorial,” Reality, A Journal of Artists’ Opinions (Spring 1954), p. 2.

- ↑ Flight lyric, Paris 1945-1956, texts Patrick-Gilles Persin, Michel and Pierre Descargues Ragon, Musée du Luxembourg, Paris and Skira, Milan, 2006, 280 p. ISBN 8876246797.

- ↑ Caroline A. Jones, [http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/21294814&referer=brief_results, Bay Area figurative art, 1950-1965, (San Francisco, California : San Francisco Museum of Modern Art ; Berkeley : University of California Press, ©1990.) ISBN 9780520068421

- ↑ American Abstract and Figurative Expressionism: Style Is Timely Art Is Timeless (New York School Press, 2009.) ISBN 9780967799421 pp. 44-47; 56-59; 80-83; 112-115; 192-195; 212-215; 240-243; 248-251

- ↑ Marika Herskovic, American Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s An Illustrated Survey, (New York School Press, 2000. ISBN 0-9677994-1-4. pp. 46-49; pp. 62-65; pp. 70-73; pp. 74-77; pp. 94-97; 262-264

- ↑ American Abstract and Figurative Expressionism: Style Is Timely Art Is Timeless: An Illustrated Survey With Artists' Statements, Artwork and Biographies(New York School Press, 2009. ISBN 9780967799421. pp.24-27; pp.28-31; pp.32-35; pp. 60-63; pp.64-67; pp.72-75; pp.76-79; pp. 112-115; 128-131; 136-139; 140-143; 144-147; 148-151; 156-159; 160-163;

- ↑ Ryan, David (2002). Talking painting: dialogues with twelve contemporary abstract painters, p.211, Routledge. ISBN 0415276292, ISBN 9780415276290. Available on Google Books.

- ↑ "Exhibition archive: Expanding Boundaries: Lyrical Abstraction", Boca Raton Museum of Art, 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ↑ "John Seery", National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ↑ Mathias Goeritz, "El manifiesto de arquitectura emocional", in Lily Kassner, Mathias Goeritz, UNAM, 2007, p. 272-273

Further reading

- Antonín Matějček cited in Gordon, Donald E. (1987). Expressionism: Art and Ideas, p. 175. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Jonah F. Mitchell (Berlin, 2003). Doctoral thesis Expressionism between Western modernism and Teutonic Sonderweg. Courtesy of the author.

- Friedrich Nietzsche (1872). The Birth of Tragedy Out of The Spirit of Music. Trans. Clifton P. Fadiman. New York: Dover, 1995. ISBN 0486285154.

- Judith Bookbinder, Boston modern: figurative expressionism as alternative modernism, (Durham, N.H. : University of New Hampshire Press; Hanover: University Press of New England, ©2005.) ISBN 1584654880 9781584654889

- Bram Dijkstra, American expressionism: art and social change, 1920-1950, (New York : H.N. Abrams, in association with the Columbus Museum of Art, 2003.) ISBN 0810942313 9780810942318

- Ditmar Elger Expressionism-A Revolution in German Art ISBN 978-3-8228-3194-6

- Paul Schimmel and Judith E Stein, The Figurative fifties : New York figurative expressionism, The Other Tradition (Newport Beach, California : Newport Harbor Art Museum : New York : Rizzoli, 1988.) ISBN 0847809420 9780847809424 0917493125 9780917493126

- Marika Herskovic, American Abstract and Figurative Expressionism: Style Is Timely Art Is Timeless (New York School Press, 2009.) ISBN 9780967799421.

External links

- Hottentots in tails A turbulent history of the group by Christian Saehrendt at signandsight.com

- Expressionism

- The Official Website of the Norris Embry Estate A free educational resource on Expressionism, including a large collection of expressionist paintings by the American artist Norris Embry (1921-1981).

- German Expressionism A free resource with paintings from German expressionists (high-quality).

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||