Extrasolar planet

An extrasolar planet, or exoplanet, is a planet outside the Solar System. As of 27 August 2010, astronomers have announced confirmed detections of 490 such planets.[1] The vast majority have been detected through radial velocity observations and other indirect methods rather than actual imaging.[1] Most are giant planets thought to resemble Jupiter; this partly reflects a sampling bias in that more massive planets are easier to observe with current technology. Several relatively lightweight exoplanets, only a few times more massive than Earth, have also been detected and projections suggest that these will eventually be found to outnumber giant planets.[2][3] It is now known that a substantial fraction of stars have planets, including at least around 10% of sun-like stars. (The true proportion may be much higher.)[4] It follows that billions of exoplanets must exist in our own galaxy alone. There also exist planets that orbit brown dwarfs and free floating planets that do not orbit any parent body at all, though as a matter of definition it is unclear if either of these should be referred to by the term "planet."

Extrasolar planets became an object of scientific investigation in the nineteenth century. Many astronomers supposed that they existed, but there was no way of knowing how common they were or how similar they might be to the planets of our solar system. The first confirmed detection was made in 1992, with the discovery of several terrestrial-mass planets orbiting the pulsar PSR B1257+12.[5] The first confirmed detection of an exoplanet orbiting a main-sequence star was made in 1995, when a giant planet, 51 Pegasi b, was found in a four-day orbit around the nearby G-type star 51 Pegasi. The frequency of detections has tended to increase on an annual basis since then.[1]

The discovery of extrasolar planets has intensified interest in the possibility of extraterrestrial life.[6] As of April 2010[update], Gliese 581 d, fourth planet of the red dwarf star Gliese 581, appears to be the best known example of a possibly terrestrial exoplanet orbiting within the habitable zone that surrounds its star. Although initial observations placed the planet outside that zone, additional measurements suggest it may reside within.[7]

Contents |

History of detection

Retracted discoveries

Unconfirmed until 1992, extrasolar planets had long been a subject of discussion and speculation. In the sixteenth century the Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno, an early supporter of the Copernican theory that the Earth and other planets orbit the Sun, put forward the view that the fixed stars are similar to the Sun and are likewise accompanied by their own planets.[8] In the eighteenth century the same possibility was mentioned by Isaac Newton in the "General Scholium" that concludes his Principia. Making a comparison to the Sun's planets, he wrote "And if the fixed stars are the centers of similar systems, they will all be constructed according to a similar design and subject to the dominion of One." [9]

Claims of exoplanet detections have been made since the nineteenth century. Some of the earliest involve the binary star 70 Ophiuchi. In 1855 Capt. W. S. Jacob at the East India Company's Madras Observatory reported that orbital anomalies made it "highly probable" that there was a "planetary body" in this system.[10] In the 1890s, Thomas J. J. See of the University of Chicago and the United States Naval Observatory stated that the orbital anomalies proved the existence of a dark body in the 70 Ophiuchi system with a 36-year period around one of the stars.[11] However, Forest Ray Moulton soon published a paper proving that a three-body system with those orbital parameters would be highly unstable.[12] During the 1950s and 1960s, Peter van de Kamp of Swarthmore College made another prominent series of detection claims, this time for planets orbiting Barnard's Star.[13] Astronomers now generally regard all the early reports of detection as erroneous.[14]

In 1991, Andrew Lyne, M. Bailes and S.L. Shemar claimed to have discovered a pulsar planet in orbit around PSR 1829-10, using pulsar timing variations.[15] The claim briefly received intense attention, but Lyne and his team soon retracted it.[16]

Confirmed discoveries

The first published discovery to have received subsequent confirmation was made in 1988 by the Canadian astronomers Bruce Campbell, G. A. H. Walker, and S. Yang.[17] Although they remained cautious about claiming a true planetary detection, their radial-velocity observations suggested that a planet orbited the star Gamma Cephei. Partly because the observations were at the very limits of instrumental capabilities at the time, widespread skepticism persisted in the astronomical community for several years about this and other similar observations. Another source of confusion was that some of the possible planets might instead have been brown dwarfs, objects that are intermediate in mass between planets and stars. The following year, however, additional observations were published that supported the reality of the planet orbiting Gamma Cephei,[18] though subsequent work in 1992 raised serious doubts.[19] Finally, in 2002, improved techniques allowed the planet's existence to be confirmed.[20]

In early 1992, radio astronomers Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail announced the discovery of planets around another pulsar, PSR 1257+12.[5] This discovery was quickly confirmed, and is generally considered to be the first definitive detection of exoplanets. These pulsar planets are believed to have formed from the unusual remnants of the supernova that produced the pulsar, in a second round of planet formation, or else to be the remaining rocky cores of gas giants that survived the supernova and then decayed into their current orbits.

On October 6, 1995, Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz of the University of Geneva announced the first definitive detection of an exoplanet orbiting an ordinary main-sequence star (51 Pegasi).[21] This discovery, made at the Observatoire de Haute-Provence, ushered in the modern era of exoplanetary discovery. Technological advances, most notably in high-resolution spectroscopy, led to the detection of many new exoplanets at a rapid rate. These advances allowed astronomers to detect exoplanets indirectly by measuring their gravitational influence on the motion of their parent stars. Additional extrasolar planets were eventually detected by observing the variation in a star's apparent luminosity as an orbiting planet passed in front of it.

To date[update], 490 exoplanets are listed in the Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia, including a few that were confirmations of controversial claims from the late 1980s.[1] The first system to have more than one planet detected was PSR 1257+12; the first confirmed to have multiple planets orbiting a main-sequence star was Upsilon Andromedae. Forty-five such multiple-planet systems are known as of May 2010[update]. Among the known exoplanets are four pulsar planets orbiting two separate pulsars. Infrared observations of circumstellar dust disks also suggest the existence of millions of comets in several extrasolar systems.

Detection methods

Planets are extremely faint light sources compared to their parent stars. At visible wavelengths, they usually have less than a millionth of their parent star's brightness. It is extremely difficult to detect such a faint light source, and furthermore the parent star causes a glare that tends to wash it out.

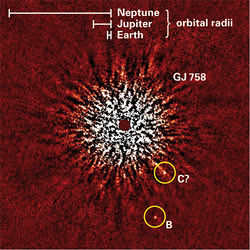

For the above reasons, telescopes have directly imaged no more than about ten exoplanets. This has only been possible for planets that are especially large (usually much larger than Jupiter) and widely separated from their parent star. Most of the directly imaged planets have also been very hot, so that they emit intense infrared radiation; the images have then been made at infrared rather than visible wavelengths, in order to reduce the problem of glare from the parent star.

A team of researchers from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory has recently demonstrated a technique for blocking a star's light with a vector vortex coronagraph, thus enabling direct detections to be made much more easily. The researchers are hopeful that many new planets may be imaged using this technique.[22][23] Another promising approach is nulling interferometry.[24]

At the moment, however, the vast majority of known extrasolar planets have only been detected through indirect methods. The following are the indirect methods that have proven useful:

- As a planet orbits a star, the star also moves in its own small orbit around the system's center of mass. Variations in the star's radial velocity — that is, the speed with which it moves towards or away from Earth — can be detected from displacements in the star's spectral lines due to the Doppler effect. Extremely small radial-velocity variations can be observed, down to roughly 1 m/s. This has been by far the most productive method of discovering exoplanets. It has the advantage of being applicable to stars with a wide range of characteristics.

- If a planet crosses (or transits) in front of its parent star's disk, then the observed brightness of the star drops by a small amount. The amount by which the star dims depends on its size and on the size of the planet, among other factors. This has been the second most productive method of detection, though it suffers from a substantial rate of false positives and confirmation from another method is usually considered necessary.

- Transit Timing Variation (TTV)

- TTV is a variation on the transit method where the variations in transit of one planet can be used to detect another. The first planetary candidate found this way was exoplanet WASP-3c, using WASP-3b in the WASP-3 system by Rozhen Observatory, Jena Observatory, and Toruń Centre for Astronomy. [25] The new method can potentially detect Earth sized planets or exomoons. [25]

- Microlensing occurs when the gravitational field of a star acts like a lens, magnifying the light of a distant background star. Planets orbiting the lensing star can cause detectable anomalies in the magnification as it varies over time. This method has resulted in only a few planetary detections, but it has the advantage of being especially sensitive to planets at large separations from their parent stars.

- Astrometry consists of precisely measuring a star's position in the sky and observing the changes in that position over time. The motion of a star due to the gravitational influence of a planet may be observable. Because that motion is so small, however, this method has not yet been very productive at detecting exoplanets.

- A pulsar (the small, ultradense remnant of a star that has exploded as a supernova) emits radio waves extremely regularly as it rotates. If planets orbit the pulsar, they will cause slight anomalies in the timing of its observed radio pulses. Four planets have been detected in this way, around two different pulsars; the first discovery of an extrasolar planet has been performed using this method.

- If a planet has a large orbit that carries it around both members of an eclipsing double star system, then the planet can be detected through small variations in the timing of the stars' eclipses of each other. As of December 2009, two planets have been found by this method.

- Disks of space dust surround many stars, and this dust can be detected because it absorbs ordinary starlight and re-emits it as infrared radiation. Features in the disks may suggest the presence of planets.

Most extrasolar planet candidates have been found using ground-based telescopes. However, many of the methods can work more effectively with space-based telescopes that avoid atmospheric haze and turbulence. COROT (launched December 2006) and Kepler (launched March 2009) are the two currently active space missions dedicated to searching for extrasolar planets. Hubble Space Telescope and MOST have also found or confirmed a few planets. There are also several planned or proposed space missions geared towards exoplanet observation, such as New Worlds Mission, Darwin, Space Interferometry Mission, Terrestrial Planet Finder and PEGASE.

Definition

The official definition of "planet" used by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) only covers the Solar System and thus takes no stance on exoplanets.[26][27] As of April 2010, the only definitional statement issued by the IAU that pertains to exoplanets is a working definition issued in 2001 and modified in 2003.[28] This definition contains the following criteria:

- Objects with true masses below the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium (currently calculated to be 13 Jupiter masses for objects of solar metallicity) that orbit stars or stellar remnants are "planets" (no matter how they formed). The minimum mass/size required for an extrasolar object to be considered a planet should be the same as that used in our solar system.

- Substellar objects with true masses above the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium are "brown dwarfs", no matter how they formed nor where they are located.

- Free-floating objects in young star clusters with masses below the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium are not "planets", but are "sub-brown dwarfs" (or whatever name is most appropriate).

This article follows the above working definition. Therefore it only discusses planets that orbit stars or brown dwarfs. (There have also been several reported detections of planetary-mass objects, sometimes called "rogue planets," that do not orbit any parent body.[29] Some of these may have once belonged to a star's planetary system before being ejected from it.)

However, it should be noted that the IAU's working definition is not universally accepted. One alternate suggestion is that planets should be distinguished from brown dwarfs on the basis of formation. It is widely believed that giant planets form through core accretion, and that process may sometimes produce planets with masses above the deuterium fusion threshold[30][31]; massive planets of that sort may have already been observed.[32] This viewpoint also admits the possibility of sub-brown dwarfs, which have planetary masses but form like stars from the direct collapse of clouds of gas.

Nomenclature

The system used in the scientific literature for naming exoplanets is almost the same as the system used for naming binary stars. The only modification is that a lowercase letter is used for the planet instead of the uppercase letter used for stars. The lowercase letter is placed after the star name, starting with "b" for the first planet found in the system (for example, 51 Pegasi b); "a" is skipped to avoid any confusion with the primary star. The next planet found in the system is labeled with the next letter in the alphabet. For instance, any more planets found around 51 Pegasi will be catalogued as "51 Pegasi c" and "51 Pegasi d", and so on. If two planets are discovered at the same time, the closer one to the star gets the next letter, followed by the farther planet. In a few cases a planet has been found closer to the star than other previously known planets, so that the letter order does not follow the order of the planets from the star. For example, in the 55 Cancri system, the most recently discovered planet is referred to as 55 Cancri f, despite the fact that it is closer to the star than 55 Cancri d. As of August 2010 the highest letter in use is "h", applied to the planet HD 10180 h.

If a planet orbits one member of a multiple-star system, then an uppercase letter for the star will be followed by a lowercase letter for the planet. Examples include the planets 16 Cygni Bb and 83 Leonis Bb. However, if the planet orbits the primary star of the system, and the secondary stars were either discovered after the planet or are relatively far form the primary star and planet, then the uppercase letter is usually omitted. For example, Tau Boötis b orbits in a binary system, but because the secondary star was both discovered after the planet and very far from the primary star and planet, the term "Tau Boötis Ab" is rarely if ever used.

Only two planetary systems have planets that are named unusually. Before the discovery of 51 Pegasi b in 1995, two pulsar planets (PSR B1257+12 B and PSR B1257+12 C) were discovered from pulsar timing of their dead star. Since there was no official way of naming planets at the time, they were called "B" and "C" (similar to how planets are named today). However, uppercase letters were used, most likely because of the way binary stars were named. When a third planet was discovered, it was designated PSR B1257+12 A (simply because the planet was closer than the other two).[33]

An alternate nomenclature, often seen in science fiction, uses Roman numerals in the order of planets' positions from the star. (This is inspired by an old system for naming moons of the outer planets, such as "Jupiter IV" for Callisto.) But such a system has proven impractical for scientific use. To use our solar system as an example, Jupiter would most likely be the first planet discovered, and Saturn the second; but, as the terrestrial planets would not be easily detected, Jupiter and Saturn would be called "Sol I" and "Sol II" by science-fiction nomenclature, and need to be renamed "Sol V" and "Sol VI" if all four terrestrial planets are discovered later. In contrast, by the current system, even if the terrestrial planets were found, Jupiter and Saturn would remain "Sol b" and "Sol c" and not need renaming.

Finally, several planets have received unofficial names comparable to those of planets in the Solar System. Among the notable planets that have been given such names are Osiris (HD 209458 b), Bellerophon (51 Pegasi b), and Methuselah (PSR B1620-26 b). The International Astronomical Union (IAU) currently has no plans to officially assign names of this sort to extrasolar planets, considering it impractical.[34]

General properties

Number of stars with planets

Planet-search programs have discovered planets orbiting a substantial fraction of the stars they have looked at. However, the total fraction of stars with planets is uncertain because of observational selection effects. The radial-velocity method and the transit method (which between them are responsible for the vast majority of detections) are most sensitive to large planets on small orbits. For that reason, many known exoplanets are "hot Jupiters": planets of roughly Jupiter-like mass on very small orbits with periods of only a few days. It is now known that 1% to 1.5% of sunlike stars possess such a planet, where "sunlike star" refers to any main-sequence star of spectral classes F, G, or K without a close stellar companion.[4] It is further estimated that 3% to 4.5% of sunlike stars possess a giant planet with an orbital period of 100 days or less, where "giant planet" means a planet of at least thirty Earth masses.[35]

The fraction of stars with smaller or more distant planets remains difficult to estimate. Extrapolation does suggest that small planets (of roughly Earth-like mass) are more common than giant planets. It also appears that planets on large orbits may be more common than ones on small orbits. Based on such extrapolation, it is estimated that perhaps 20% of sunlike stars have at least one giant planet while at least 40% may have planets of lower mass.[35][36][37]

Regardless of the exact fraction of stars with planets, the total number of exoplanets must be very large. Since our own Milky Way Galaxy has at least 200 billion stars, it must also contain billions of planets if not hundreds of billions of them.

Characteristics of planet-hosting stars

Most known exoplanets orbit stars roughly similar to our own Sun, that is, main-sequence stars of spectral categories F, G, or K. One reason is simply that planet search programs have tended to concentrate on such stars. But even after taking this into account, statistical analysis indicates that lower-mass stars (red dwarfs, of spectral category M) are either less likely to have planets or have planets that are themselves of lower mass and hence harder to detect.[35][38] Recent observations by the Spitzer Space Telescope indicate that stars of spectral category O, which are much hotter than our Sun, produce a photo-evaporation effect that inhibits planetary formation.[39]

Stars are composed mainly of the light elements hydrogen and helium. They also contain a small fraction of heavier elements such as iron, and this fraction is referred to as a star's metallicity. Stars of higher metallicity are much more likely to have planets, and the planets they have tend to be more massive than those of lower-metallicity stars.[4] It has also been shown that stars with planets are more likely to be deficient in lithium.[40]

Orbital parameters

|

astrometry transit timing

|

direct imaging microlensing

|

radial velocity pulsar timing

|

Most known extrasolar planet candidates have been discovered using indirect methods and therefore only some physical and orbital parameters can be determined. For example, out of the six independent parameters that define an orbit, the radial-velocity method can determine four: semi-major axis, eccentricity, longitude of periastron, and time of periastron. Two parameters remain unknown: inclination and longitude of the ascending node.

Many exoplanets have orbits with very small semi-major axes, and are thus much closer to their parent star than any planet in our own solar system is to the Sun. That fact, however, is mainly due to observational selection: The radial-velocity method is most sensitive to planets with small orbits. Astronomers were initially very surprised by these "hot Jupiters", but it is now clear that most exoplanets (or, at least, most high-mass exoplanets) have much larger orbits, some located in habitable zones where suitable for liquid water and life.[35] It appears plausible that in most exoplanetary systems, there are one or two giant planets with orbits comparable in size to those of Jupiter and Saturn in our own solar system. Giant planets with substantially larger orbits are now known to be rare, at least around sun-like stars.[41]

The eccentricity of an orbit is a measure of how elliptical (elongated) it is. Most exoplanets with orbital periods of 20 days or less have near-circular orbits of very low eccentricity. That is believed to be due to tidal circularization, an effect in which the gravitational interaction between two bodies gradually reduces their orbital eccentricity. By contrast, most known exoplanets with longer orbital periods have quite eccentric orbits. (As of July 2010, 55% of such exoplanets have eccentricities greater than 0.2 while 17% have eccentricities greater than 0.5.[1]) This is not an observational selection effect, since a planet can be detected about equally well regardless of the eccentricity of its orbit. The prevalence of elliptical orbits is a major puzzle, since current theories of planetary formation strongly suggest planets should form with circular (that is, non-eccentric) orbits.[14]

The prevalence of eccentric orbits may also indicate that our own solar system is somewhat unusual, since all of its planets except for Mercury have near-circular orbits.[4]

However, it has recently been suggested that some of the high eccentricity values reported for exoplanets may be overestimates, since simulations show that many observations are also consistent with two planets on circular orbits. Planets reported as single moderately eccentric planets have a ~15% chance of being part of such a pair.[42] This misinterpretation is especially likely if the two planets orbit with a 2:1 resonance. One group of astronomers has concluded that "(1) around 35% of the published eccentric one-planet solutions are statistically indistinguishable from planetary systems in 2:1 orbital resonance, (2) another 40% cannot be statistically distinguished from a circular orbital solution" and "(3) planets with masses comparable to Earth could be hidden in known orbital solutions of eccentric super-Earths and Neptune mass planets."[43]

A combination of astrometric and radial velocity measurements has revealed that some planetary systems differ from our Solar System by containing planets whose orbital planes are significantly tilted relative to each other.[44] Research has now also shown that more than half of hot Jupiters have orbital planes substantially misaligned with their parent stars' rotation. A substantial fraction even have retrograde orbits, meaning that they orbit in the opposite direction from the star's rotation.[45] Andrew Cameron of the University of St Andrews stated, “The new results really challenge the conventional wisdom that planets should always orbit in the same direction as their stars spin." [46]Rather than a planet's orbit having been disturbed, it may be that the star itself flipped over early in their system's formation due to interactions between the star's magnetic field and the planet-forming disc.[47]

Mass distribution

When a planet is found by the radial-velocity method, its orbital inclination i is unknown. The method is unable to determine the true mass of the planet, but rather gives its minimum mass M sini. In a few cases an apparent exoplanet may actually be a more massive object such as a brown dwarf or red dwarf. However, statistically the factor of sini takes on an average value of π/4≈0.785 and hence most planets will have true masses fairly close to the minimum mass.[35] Furthermore, if the planet's orbit is nearly perpendicular to the sky (with an inclination close to 90°), the planet can also be detected through the transit method. The inclination will then be known, and the planet's true mass can be found. Also, astrometric observations and dynamical considerations in multiple-planet systems can sometimes be used to constrain a planet's true mass.

The vast majority of exoplanets detected so far have high masses. As of January 2010, all but twenty-five of them have more than ten times the mass of Earth.[1] Many are considerably more massive than Jupiter, the most massive planet in the Solar System. However, these high masses are in large part due to an observational selection effect: all detection methods are much more likely to discover massive planets. This bias makes statistical analysis difficult, but it appears that lower-mass planets are actually more common than higher-mass ones, at least within a broad mass range that includes all giant planets. In addition, the fact that astronomers have found several planets only a few times more massive than Earth, despite the great difficulty of detecting them, indicates that such planets are fairly common.[4]

The results from the first 43 days of Kepler mission "imply that small candidate planets with periods less than 30 days are much more common than large candidate planets with periods less than 30 days and that the ground-based discoveries are sampling the large-size tail of the size distribution"[48]

Temperature and composition

It is possible to estimate the temperature of an exoplanet based on the intensity of the light it receives from its parent star. For example, the planet OGLE-2005-BLG-390Lb is estimated to have a surface temperature of roughly -220°C (roughly 50 K). However, such estimates may be substantially in error because they depend on the planet's usually unknown albedo, and because factors such as the greenhouse effect may introduce unknown complications. A few planets have had their temperature measured by observing the variation in infrared radiation as the planet moves around in its orbit and is eclipsed by its parent star. For example, the planet HD 189733b has been found to have an average temperature of 1205±9 K (932±9°C) on its dayside and 973±33 K (700±33°C) on its nightside.[49]

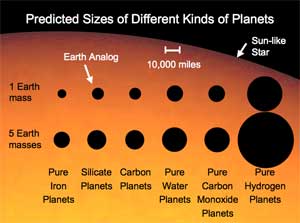

If a planet is detectable by both the radial-velocity and the transit methods, then both its true mass and its radius can be found. The planet's density can then be calculated. Planets with low density are inferred to be composed mainly of hydrogen and helium, while planets of intermediate density are inferred to have water as a major constituent. A planet of high density is believed to be rocky, like Earth and the other terrestrial planets of the Solar System.

Spectroscopic measurements can be used to study a transiting planet's atmospheric composition.[50] Water vapor, sodium vapor, methane, and carbon dioxide have been detected in the atmospheres of various exoplanets in this way. The technique might conceivably discover atmospheric characteristics that suggest the presence of life on an exoplanet, but no such discovery has yet been made.

Another line of information about exoplanetary atmospheres comes from observations of orbital phase functions. Extrasolar planets have phases similar to the phases of the Moon. By observing the exact variation of brightness with phase, astronomers can calculate particle sizes in the atmospheres of planets.

Stellar light becomes polarized when it interacts with atmospheric molecules, which could be detected with a polarimeter. So far, one planet has been studied by polarimetry.

Unanswered questions

Many unanswered questions remain about the properties of exoplanets. One puzzle is that many transiting exoplanets are much larger than expected given their mass, meaning that they have surprisingly low density. Several theories have been proposed to explain this observation, but none have yet been widely accepted among astronomers.[51] Another question is how likely exoplanets are to possess moons. No such moons have yet been detected, but they may be fairly common.

Perhaps the most interesting question about exoplanets is whether they might support life. Several planets do have orbits in their parent star's habitable zone, where it should be possible for liquid water to exist and for Earth-like conditions to prevail. Most of those planets are giant planets more similar to Jupiter than to Earth; if any of them have large moons, the moons might be a more plausible abode of life.

Various estimates have been made as to how many planets might support simple life or even intelligent life. For example, Dr. Alan Boss of the Carnegie Institution of Science estimates there may be a "hundred billion" terrestrial planets in our Milky Way Galaxy, many with simple lifeforms. He further believes there could be thousands of civilizations in our galaxy. Recent work by Duncan Forgan of Edinburgh University has also tried to estimate the number of intelligent civilizations in our galaxy. The research suggested there could be thousands of them.[52] However, due to the great uncertainties regarding the origin and development of life and intelligence, all such estimates must be regarded as extremely speculative. Apart from the scenario of an extraterrestrial civilization that is emitting powerful signals, the detection of life at interstellar distances is a tremendously challenging technical task that will not be feasible for many years, even if such life is commonplace.

See also

Lists

- List of extrasolar planets

- List of extrasolar planet extremes

- List of unconfirmed exoplanets

Classifications

- Sudarsky extrasolar planet classification

- Pulsar planet

- Super-Earth

- Hot Neptune

- Hot Jupiter

- Eccentric Jupiter

- Gas giant

- Goldilocks planet

- Terrestrial planet

- Chthonian planet

- Ocean planet

- Carbon planet

- Iron planet

- Helium planet

- Coreless planet

Systems

- Binary star

- Hypothetical planet

- Interstellar planet

- Planetary system

- Extrasolar moon

- Extragalactic planet

Habitability and life

- Planetary habitability

- Extraterrestrial life

- Extraterrestrial liquid water

- Astrobiology

- Rare Earth hypothesis

- Fermi paradox

- Drake equation

Astronomers

- Geoffrey Marcy – co-discoverer with R. Paul Butler and Debra Fischer of more exoplanets than anyone else

- R. Paul Butler – co-discoverer with Geoffrey Marcy and Debra Fischer of more exoplanets than anyone else

- Debra Fischer – co-discoverer with Geoffrey Marcy and R. Paul Butler of more exoplanets than anyone else

- Aleksander Wolszczan – co-discoverer of PSR B1257+12 B and C, the first ever discovered exoplanets, with Dale Frail

- Dale Frail – co-discoverer of PSR B1257+12 B and C, the first ever discovered exoplanets, with Aleksander Wolszczan

- Michel Mayor – co-discoverer of 51 Pegasi b, the first ever discovered exoplanet orbiting a Sun-like star, with Didier Queloz

- Didier Queloz – co-discoverer of 51 Pegasi b, the first ever discovered exoplanet orbiting a Sun-like star, with Michel Mayor

- Stephane Udry – co-discoverer of Gliese 581 c, the most Earth-like planet

- David Charbonneau − co-discoverer of HD 209458b, the first transiting exoplanet, and GJ 1214 b, a transiting super-Earth

Observatories and methods

- Methods of detecting extrasolar planets

- Anglo-Australian Planet Search

- California & Carnegie Planet Search

- East-Asian Planet Search Network (EAPSNet)

- Geneva Extrasolar Planet Search

- High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS)

- HATNet Project (HAT)

- Automated Planet Finder at Lick Observatory

- MEarth Project

- Microlensing Observations in Astrophysics (MOA)

- Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE)

- Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI)

- SuperWASP (WASP)

- Systemic, an amateur search project

- Trans-Atlantic Exoplanet Survey (TrES)

- XO Telescope (XO)

- Magellan Planet Search Program

- Okayama Planet Search Program

- Sagittarius Window Eclipsing Extrasolar Planet Search

- ELODIE spectrograph

- CORALIE spectrograph

- SOPHIE échelle spectrograph

- ZIMPOL/CHEOPS, based at VLT.

- Gemini Planet Imager

Missions

- COROT – launched in 2006

- Kepler Mission – launched in 2009

- PEGASE – launch between 2010–2012

- Space Interferometry Mission – launch between 2015–2016

- New Worlds Mission – launch in 2014

- Terrestrial Planet Finder – no launch date

- Darwin – launch in 2016

- Gaia mission – launch in 2012

- PLATO – launch in 2017

- TESS – launch between 2013–2014

Books

- Planets in science fiction

- Distant Wanderers

- Infinite Worlds: An Illustrated Voyage to Planets Beyond Our Sun

Websites

- The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 J. Schneider (2010). "Interactive Extra-solar Planets Catalog". The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia. http://exoplanet.eu/catalog.php. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ↑ "Rock planets outnumber gas giants". Virgin Media. 28 May 2008. http://latestnews.virginmedia.com/news/tech/2008/05/28/rock_planets_outnumber_gas_giants?showCommentThanks=true. Retrieved 2000-12-06.

- ↑ Characteristics of Kepler Planetary Candidates Based on the First Data Set: The Majority are Found to be Neptune-Size and Smaller, William J. Borucki, for the Kepler Team (Submitted on 14 Jun 2010)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 G. Marcy et al. (2005). "Observed Properties of Exoplanets: Masses, Orbits and Metallicities". Progress of Theoretical Physics Supplement 158: 24–42. doi:10.1143/PTPS.158.24. http://ptp.ipap.jp/link?PTPS/158/24.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 doi:10.1038/355145a0

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ "Terrestrial Planet Finder science goals: Detecting signs of life". Terrestrial Planet Finder. JPL/NASA. http://planetquest.jpl.nasa.gov/TPF/tpf_signsOfLife.cfm. Retrieved 2006-07-21.

- ↑ M. Mayor et al. (2009). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets: XVIII. An Earth-mass planet in the GJ 581 planetary system". Astronomy and Astrophysics 507: 487–494. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912172. arXiv:0906.2780.

- ↑ "Cosmos" in The New Encyclopædia Britannica (15th edition, Chicago, 1991) 16:787:2a. "For his advocacy of an infinity of suns and earths, he was burned at the stake in 1600."

- ↑ Newton, Isaac; I. Bernard Cohen and Anne Whitman (1999 [1713]). The Principia: A New Translation and Guide. University of California Press. p. 940.

- ↑ W.S Jacob (1855). "On Certain Anomalies presented by the Binary Star 70 Ophiuchi". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 15: 228. http://books.google.com/?id=pQsAAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=editions:0B0EaWqbmirpeTa2sds.

- ↑ T.J.J. See (1896). "Researches on the Orbit of F.70 Ophiuchi, and on a Periodic Perturbation in the Motion of the System Arising from the Action of an Unseen Body". Astronomical Journal 16: 17. doi:10.1086/102368.

- ↑ T.J. Sherrill (1999). "A Career of Controversy: The Anomaly of T. J. J. See". Journal for the History of Astronomy 30 (98): 25–50. http://www.shpltd.co.uk/jha.pdf.

- ↑ P. van de Kamp (1969). "Alternate dynamical analysis of Barnard's star". Astronomical Journal 74: 757–759. doi:10.1086/110852. Bibcode: 1969AJ.....74..757V.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Boss, Alan (2009). The Crowded Universe: The Search for Living Planets. Basic Books. pp. 31--32. ISBN 978-0-465-00936-7.

- ↑ M. Bailes, A.G. Lyne, S.L. Shemar (1991). "A planet orbiting the neutron star PSR1829-10". Nature 352: 311–313. doi:10.1038/352311a0. http://www.nature.com/cgi-taf/DynaPage.taf?file=/nature/journal/v352/n6333/abs/352311a0.html.

- ↑ A.G Lyne, M. Bailes (1992). "No planet orbiting PS R1829-10". Nature 355 (6357): 213. doi:10.1038/355213b0. http://www.nature.com/cgi-taf/DynaPage.taf?file=/nature/journal/v355/n6357/abs/355213b0.html.

- ↑ doi:10.1086/166608

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ A.T. Lawton, P. Wright (1989). "A planetary system for Gamma Cephei?". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society 42: 335–336. Bibcode: 1989JBIS...42..335L.

- ↑ G.A.H. Walker et al. (1992). "Gamma Cephei – Rotation or planetary companion?". Astrophysical Journal Letters 396 (2): L91–L94. doi:10.1086/186524. Bibcode: 1992ApJ...396L..91W.

- ↑ A.P. Hatzes et al. (2003). "A Planetary Companion to Gamma Cephei A". Astrophysical Journal 599 (2): 1383–1394. doi:10.1086/379281.

- ↑ M. Mayor, D. Queloz (1995). "A Jupiter-mass companion to a solar-type star". Nature 378: 355–359. doi:10.1038/378355a0. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v378/n6555/abs/378355a0.html.

- ↑ New method could image Earth-like planets

- ↑ E. Serabyn, D. Mawet, R. Burruss (2010). "An image of an exoplanet separated by two diffraction beamwidths from a star". Nature 464 (7291): 1018. doi:10.1038/nature09007. PMID 20393557. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v464/n7291/full/nature09007.html.

- ↑ Earth-like Planets May Be Ready for Their Close-Up

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 http://www.scientificcomputing.com/news-DS-Planet-Hunting-Finding-Earth-like-Planets-071910.aspx "Planet Hunting: Finding Earth-like Planets"

- ↑ "IAU 2006 General Assembly: Result of the IAU Resolution votes". 2006. http://www.iau.org/public_press/news/detail/iau0603/. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ↑ R.R. Brit (2006). "Why Planets Will Never Be Defined". Space.com. http://www.space.com/aol/061121_exoplanet_definition.html. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ↑ "Working Group on Extrasolar Planets: Definition of a "Planet"". IAU position statement. 28 February 2003. http://www.dtm.ciw.edu/boss/definition.html. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ↑ Kenneth A. Marsh, J. Davy Kirkpatrick, and Peter Plavchan (2009). "A Young Planetary-Mass Object in the rho Oph Cloud Core". Astrophysical Journal Letters (forthcoming). http://fr.arxiv.org/abs/0912.3774.

- ↑ Mordasini, C. et al. (2007). "Giant Planet Formation by Core Accretion". arΧiv:0710.5667v1 [astro-ph].

- ↑ Baraffe, I. et al. (2008). "Structure and evolution of super-Earth to super-Jupiter exoplanets. I. Heavy element enrichment in the interior". Astronomy and Astrophysics 482 (1): 315–332. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20079321. http://arxiv.org/abs/0802.1810.

- ↑ Bouchy, F. et al. (2009). "The SOPHIE search for northern extrasolar planets . I. A companion around HD 16760 with mass close to the planet/brown-dwarf transition". Astronomy and Astrophysics 505 (2): 853–858. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912427. http://www.arxiv.org/abs/0907.3559.

- ↑ "Naming Extrasolar Planets (Nomenclature)". Extrasolar Planets. Miami University. http://www.users.muohio.edu/weaksjt/#naming. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ↑ "Planets Around Other Stars". International Astronomical Union. http://www.iau.org/public_press/themes/extrasolar_planets/. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 Andrew Cumming, R. Paul Butler, Geoffrey W. Marcy, et al. (2008). "The Keck Planet Search: Detectability and the Minimum Mass and Orbital Period Distribution of Extrasolar Planets". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 120: 531–554. doi:10.1086/588487. Archived from the original on 05/2008. http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/588487.

- ↑ "Scientists announce planet bounty". BBC News. 2009-10-19. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/8314581.stm. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- ↑ David P. Bennett, Jay Anderson, Ian A. Bond, Andrzej Udalski, and Andrew Gould (2006). "Identification of the OGLE-2003-BLG-235/MOA-2003-BLG-53 Planetary Host Star". Astrophysical Journal Letters 647: L171–L174. doi:10.1086/507585. http://iopscience.iop.org/1538-4357/647/2/L171.

- ↑ X. Bonfils et al. (2005). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets: VI. A Neptune-mass planet around the nearby M dwarf Gl 581". Astronomy & Astrophysics 443: L15–L18. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200500193.

- ↑ L. Vu (3 October 2006). "Planets Prefer Safe Neighborhoods". Spitzer Science Center. http://www.spitzer.caltech.edu/Media/happenings/20061003/. Retrieved 2007-09-01.

- ↑ G. Israelian et al. (2009). "Enhanced lithium depletion in Sun-like stars with orbiting planets". Nature 462 (7270): 189–191. doi:10.1038/nature08483. PMID 19907489. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v462/n7270/abs/nature08483.html.

- ↑ Eric L. Nielsen and Laird M. Close (2010). "A Uniform Analysis of 118 Stars with High-Contrast Imaging: Long-Period Extrasolar Giant Planets are Rare around Sun-like Stars". Astrophysical Journal 717 (2): 878. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/717/2/878. http://iopscience.iop.org/0004-637X/717/2/878.

- ↑ T. Rodigas; Hinz (2009). "Which Radial Velocity Exoplanets Have Undetected Outer Companions?". arΧiv:0907.0020 [astro-ph.EP].

- ↑ Guillem Anglada-Escudé, Mercedes López-Morales and John E. Chambers (2010). "How Eccentric Orbital Solutions Can Hide Planetary Systems in 2:1 Resonant Orbits". Astrophysical Journal 709 (1): 168. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/709/1/168. http://iopscience.iop.org/0004-637X/709/1/168.

- ↑ Out of Flatland: Orbits Are Askew in a Nearby Planetary System, www.scientificamerican.com, may 24, 2010

- ↑ Turning planetary theory upside down

- ↑ "Dropping a Bomb About Exoplanets". Universe Today. 2009-04-13. http://www.universetoday.com/2010/04/13/dropping-a-bomb-about-exoplanets/. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ↑ Tilting stars may explain backwards planets, New Scientist, 01 September 2010, Magazine issue 2776.

- ↑ Characteristics of Kepler Planetary Candidates Based on the First Data Set: The Majority are Found to be Neptune-Size and Smaller, William J. Borucki, for the Kepler Team (Submitted on 14 Jun 2010)

- ↑ Heather Knutson, David Charbonneau, Lori Allen, et.al. (2007). "A map of the day-night contrast of the extrasolar planet HD 189733b". Nature 447 (7141): 183–186. doi:10.1038/nature05782. PMID 17495920. Archived from the original on 05/10/2007. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v447/n7141/abs/nature05782.html.

- ↑ D. Charbonneau, T. Brown; A. Burrows; G. Laughlin (2006). "When Extrasolar Planets Transit Their Parent Stars". Protostars and Planets V. University of Arizona Press. http://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0603376.

- ↑ I. Baraffe and G. Chabrier and T. Barman (2010). "The physical properties of extra-solar planets". Reports on Progress in Physics 73 (016901): 1. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/73/1/016901.

- ↑ "Number of alien worlds quantified". London: BBC News. 5 February 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/7870562.stm. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

External links

Search projects

- University of California Planet Search Project

- The Geneva Extrasolar Planet Search Programmes

- PlanetQuest distributed computing project

- SuperWASP Wide Angle Search for Planets

Resources

- NASA's PlanetQuest

- Exoplanet database for iPhone/iPod/iPad with visualisations

- Audio - Pamela Gay/Chris Lintott (2009) Astronomy Cast A Zoo of Extra-Solar Planets

- Standard3D Stereoscopic Space Exploration Simulator including 30 exoplanets

- The detection and characterization of exoplanets

- Beyond Our Solar System by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- German Center for Exo-Planet Research Jena/Tautenburg

- Astrophysical Institute & University Observatory Jena (AIU)

- The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia

- exosolar.net 3D Flash StarMap (2000 Stars and all known Exoplanets)

- Transiting Exoplanet Light Curves Using Differential Photometry

- Table of known planetary systems

- Extrasolar Planet XML Database

- searchable dynamic database of extrasolar planets and their parent stars

- List of important exoplanets

- Extrasolar Planets – D. Montes, UCM

- Exoplanets at Paris Observatory

- NASA Star and Exoplanet Database (NStED)

- Planetary Society Catalog of Exoplanets

- "Exoplanets in relation to host star's current habitable zone". www.planetarybiology.com. http://www.planetarybiology.com/exoexplorer_planets/.

- "exoExplorer: a free Windows application for visualizing exoplanet environments in 3D". www.planetarybiology.com. http://www.planetarybiology.com/exoexplorer/.

- Frontiers and Controversies in Astrophysics: Discovering Exoplanets — a free course and lecture series by Prof. Charles Bailyn of Yale University

- Doyle, Laurence R. (19 March 2009). "Naming New Extrasolar Planets". SETI institute. SPACE.com. http://www.space.com/searchforlife/090319-seti-planet-nomenclature.html. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

News

- Exoplanet Caught on the Move For the first time, astronomers have been able to directly follow the motion of an exoplanet as it moves from one side of its host star to the other.

- 6–8 Earth-Mass Planet Discovered orbiting Gliese 876

- Earth Sized Planets Confirmed from space.com

- "On the possible correlation between the orbital periods of extrasolar planets and the metallicity of the host stars". Wiley Interscience. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118763068/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- John T. Trauger & Wesley A. Traub (2007). "A laboratory demonstration of the capability to image an Earth-like extrasolar planet". Nature 446 (7137): 771–773. doi:10.1038/nature05729. PMID 17429394. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v446/n7137/full/nature05729.html.

- Mark R. Swain, Gautam Vasisht & Giovanna Tinetti (2008). "The presence of methane in the atmosphere of an extrasolar planet". Nature 452 (7185): 329–331. doi:10.1038/nature06823. PMID 18354477. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v452/n7185/full/nature06823.html.

- Artie P. Hatzes & Günther Wuchter (2005). "Astronomy: Giant planet seeks nursery place". Nature 436 (7048): 182–183. doi:10.1038/436182a. PMID 16015311. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v436/n7048/full/436182a.html.

- "Radio Detection of Extrasolar Planets: Present and Future Prospects" (PDF). NRL, NASA/GSFC, NRAO, Observatoìre de Paris. http://www.ece.vt.edu/swe/lwa/memo/lwa0013.pdf. Retrieved 2008-10-15.

- APOD: Likely first direct image of extra-solar planet

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||