Eurovision Song Contest

The Eurovision Song Contest (French: Concours Eurovision de la Chanson)[1] is an annual competition held among active member countries of the European Broadcasting Union (EBU).

Each member country submits a song to be performed on live television and then casts votes for the other countries' songs to determine the most popular song in the competition. Each country participates via one of their national EBU-member television stations, whose task it is to select a singer and a song to represent their country in the international competition. The Contest has been broadcast every year since its inauguration in 1956 and is one of the longest-running television programmes in the world. It is also one of the most-watched non-sporting events in the world,[2] with audience figures having been quoted in recent years as anything between 100 million and 600 million internationally.[3][4] Eurovision has also been broadcast outside Europe to such places as Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Egypt, India, Japan, Jordan, Mexico, New Zealand, the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand and Uruguay despite the fact that they do not compete.[5][6][7] Since 2000, the Contest has also been broadcast over the Internet,[8] with more than 74,000 people in almost 140 countries having watched the 2006 edition online.[9]

Contents |

Origins

In the 1950s, as a war-torn Europe rebuilt itself, the European Broadcasting Union (EBU)—based in Switzerland—set up an ad-hoc committee to search for ways of bringing together the countries of the EBU around a "light entertainment programme".[10] At a committee meeting held in Monaco in January 1955, director general of Swiss television and committee chairman Marcel Bezençon conceived the idea of an international song contest where countries would participate in one television programme, to be transmitted simultaneously to all countries of the union.[10][11] The competition was based upon the existing Sanremo Music Festival held in Italy,[12] and was also seen as a technological experiment in live television: as in those days, it was a very ambitious project to join many countries together in a wide-area international network. Satellite television did not exist, and the so-called Eurovision Network comprised a terrestrial microwave network.[13] The concept, then known as "Eurovision Grand Prix", was approved by the EBU General Assembly in at a meeting held in Rome on 19 October 1955 and it was decided that the first contest would take place in spring 1956 in Lugano, Switzerland.[10] The name "Eurovision" was first used in relation to the EBU's network by British journalist George Campey in the London Evening Standard in 1951.[11]

The first Contest was held in the town of Lugano, Switzerland, on 24 May 1956. Seven countries participated—each submitting two songs, for a total of 14. This was the only Contest in which more than one song per country was performed: since 1957 all Contests have allowed one entry per country. The 1956 Contest was won by the host nation, Switzerland.[14]

The programme was first known as the "Eurovision Grand Prix". This "Grand Prix" name was adopted by the Francophone countries, where the Contest became known as "Le Grand-Prix Eurovision de la Chanson Européenne".[15] The "Grand Prix" has since been dropped and replaced with "Concours" (contest) in these countries. The Eurovision Network is used to carry many news and sports programmes internationally, among other specialised events organised by the EBU.[16] However, in the minds of the public, the name "Eurovision" is most closely associated with the Song Contest.[13]

Format

The format of the Contest has changed over the years, though the basic tenets have always been thus: participant countries submit songs, which are performed live in a television programme transmitted across the Eurovision Network by the EBU simultaneously to all countries.[17] A "country" as a participant is represented by one television broadcaster from that country: typically, but not always, that country's national public broadcasting organisation. The programme is hosted by one of the participant countries, and the transmission is sent from the auditorium in the host city. During this programme, after all the songs have been performed, the countries then proceed to cast votes for the other countries' songs: nations are not allowed to vote for their own song.[18] At the end of the programme, the winner is declared as the song with the most points. The winner receives, simply, the prestige of having won—although it is usual for a trophy to be awarded to the winning songwriters, and the winning country is invited to host the event the following year.[14]

The programme is invariably opened by one or more presenters, welcoming viewers to the show. Most host countries choose to capitalise on the opportunity afforded them by hosting a programme with such a wide-ranging international audience, and it is common to see the presentation interspersed with video footage of scenes from the host nation, as if advertising for tourism. Between the songs and the announcement of the voting, an interval act is performed. These acts can be any form of entertainment imaginable. Interval entertainment has included such acts as The Wombles (1974)[19] and the first international presentation of Riverdance (1994).[20]

The theme music played before and after the broadcasts of the Eurovision Song Contest (and other Eurovision broadcasts) is the prelude to Marc-Antoine Charpentier's Te Deum.[11]

The Eurovision Song Contest final is traditionally held on a spring Saturday evening, at 19:00 UTC (20:00 BST, or 21:00 CEST). Usually one Saturday in May is chosen, although the Contest has been held on a Thursday (in 1956)[21] and as early as March.[22]

Participation

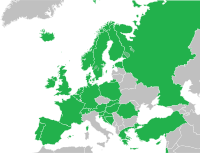

Eligible participants include Active Members (as opposed to Associate Members) of the EBU. Active members are those whose states fall within the European Broadcasting Area, or otherwise those who are members of the Council of Europe.[23]

The European Broadcasting Area is defined by the International Telecommunication Union:[24]

- The "European Broadcasting Area" is bounded on the west by the western boundary of Region 1 (see below), on the east by the meridian 40° East of Greenwich and on the south by the parallel 30° North so as to include the western part of the USSR, the northern part of Saudi Arabia and that part of those countries bordering the Mediterranean within these limits. In addition, Iraq, Jordan and that part of the territory of Turkey lying outside the above limits are included in the European Broadcasting Area.

The western boundary of Region 1 is defined by a line running from the North Pole along meridian 10° West of Greenwich to its intersection with parallel 72° North; thence by great circle arc to the intersection of meridian 50° West and parallel 40° North; thence by great circle arc to the intersection of meridian 20° West and parallel 10° South; thence along meridian 20° West to the South Pole.[25]

Active members include broadcasting organisations whose transmissions are made available to at least 98% of households in their own country which are equipped to receive such transmissions.[23]

If an EBU Active Member wishes to participate, they must fulfil conditions as laid down by the rules of the Contest (of which a separate copy is drafted annually). As of 2011, this includes the necessity to have broadcast the previous year's programme within their country, and paid the EBU a participation fee in advance of the deadline specified in the rules of the Contest for the year in which they wish to participate.

Eligibility to participate is not determined by geographic inclusion within the continent of Europe, despite the "Euro" in "Eurovision" — nor does it have any relation to the European Union. Several countries geographically outside the boundaries of Europe have competed: Israel, Cyprus, Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan in Western Asia, since 1973, 1981, 2006, 2007 and 2008 respectively; and Morocco, in North Africa, in the 1980 competition alone. In addition, Turkey and Russia, which are both transcontinental countries with most of their territory outside of Europe, have competed respectively since 1975 and 1994.[26]

Fifty-one countries have participated at least once.[27] These are listed here alongside the year in which they made their début:

| Year | Country making its début entry |

|---|---|

| 1956 | |

| 1957 | |

| 1958 | |

| 1959 | |

| 1960 | |

| 1961 | |

| 1964 | |

| 1965 | |

| 1971 | |

| 1973 | |

| 1974 | |

| 1975 | |

| 1980 | |

| 1981 | |

| 1986 | |

| 1993 | |

| 1994 | |

| 1998 | |

| 2000 | |

| 2003 | |

| 2004 | |

| 2005 | |

| 2006 | |

| 2007 | |

| 2008 |

- a) Before German reunification in 1990 occasionally presented as West Germany, representing the Federal Republic of Germany. East Germany (the German Democratic Republic) did not compete.

- b) The entries presented as being from "Yugoslavia" represented the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, except for the 1992 entry, which represented the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. This nation dissolved in 1991/1992 into five independent states: Slovenia, Croatia, Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia reconstituted itself as Serbia and Montenegro in 2003—entered the Contest in 2004—and finally dissolved in 2006, making two separate states: Serbia and Montenegro; both of which débuted in the Contest in 2007.

Selection procedures

Each country must submit one song to represent them in any given year they participate. The only exception to this was when each country submitted two songs in the inaugural Contest. There is a rule which forbids any song being entered which has been previously commercially released or broadcast in public before a certain date relative to the Contest in question.[28]

Countries may select their songs by any means, whether by an internal decision of the participating broadcaster or a public contest that allows the country's public to televote between several songs. The EBU encourages broadcasters to use the latter, as this generates more publicity for the contest. These public selections are known as national finals.[29]

Some countries' national finals are as big as—if not bigger than—the international Eurovision Song Contest itself, involving many songs being submitted to national semi-finals.[30] The Swedish national final, Melodifestivalen (literally, "The Song Festival") includes 32 songs being performed over four semi-finals, played to huge audiences in arenas around the country, before the final show in Stockholm. This has become the most-watched programme of the year in Sweden.[31] In Spain, the reality show Operación Triunfo started in 2002; the winners of the first three seasons proceeded to represent the country at Eurovision.[32]

Regardless of the method used to select the entry, the song's details must be finalised and submitted to the EBU before a deadline some weeks before the international Contest.[33]

Since 1971, each participating country has been required to provide a preview video of their entry, ostensibly to be broadcast in all the nations taking part. Broadcast of the previews was compulsory until the mid 1990s, but is no longer so, providing each country provides access to the videos online.

Hosting

Most of the expense of the contest is covered by commercial sponsors and contributions from the other participating nations. The contest is considered to be a unique opportunity for promoting the host country as a tourist destination. In the summer of 2005, Ukraine abolished its normal visa requirement for visitors from the EU to coincide with its hosting of the event.[34]

Preparations for the event start a matter of weeks after the host wins in the previous year, and confirms to the EBU that they intend to—and have the capacity to—host the event. A host city is chosen—usually the capital—and a suitable concert venue. The largest concert venue was a football stadium in Copenhagen—Parken—which held approximately 38,000 people when Denmark were the 2001 hosts.[14] The smallest town to have been hosts was Millstreet in County Cork, Ireland, in 1993. The village had a population of 1,500[35]—although the Green Glens Arena venue could hold up to 8,000 people.[36]

The hotel and press facilities in the vicinity are always a consideration when choosing a host city and venue.[37] In Kiev 2005, hotel rooms were scarce as the Contest organisers asked the Ukrainian government to put a block on bookings they did not control themselves through official delegation allocations or tour packages: this led to many people's hotel bookings being cancelled.[38]

Eurovision Week

The term "Eurovision Week" is used to refer to the week during which the Contest takes place.[39] As it is a live show, the Eurovision Song Contest requires the performers to have perfected their acts in rehearsals in order for the big night to run smoothly. In addition to rehearsals in their home countries, every participant is given the opportunity to rehearse on the stage in the Eurovision auditorium. These rehearsals are held during the course of several days before the Saturday show, and consequently the delegations arrive in the host city many days before the event. This means, in turn, journalists and fans are also present during the preceding days, and the events of Eurovision last a lot longer than a few hours of television. A number of officially accredited hotels are selected for the delegations to stay in, and shuttle-bus services are used to transport the performers and accompanying people to and from the Contest venue.[40]

Each participating broadcaster nominates a Head of Delegation, whose job it is to coordinate the movements of the delegate members, and who acts as that country's representative to the EBU in the host city.[28] Members of the delegations include performers, lyricists, composers, official press officers and—in the years where songs were performed with a live orchestra—a conductor. Also present if desired is a commentator: each broadcaster may supply their own commentary for their TV and/or radio feed, to be broadcast in each country. The commentators are given dedicated commentary booths situated around the back of the arena behind the audience.

Rehearsals and press conferences

Traditionally, delegations would arrive on the Sunday before the Contest, in order to be present for rehearsals starting on the Monday morning. However, with the introduction of the semi-final—and therefore the resulting increase in the number of countries taking part—since 2004 the first rehearsals have commenced during the week before Eurovision Week. The countries taking part in the semi-final currently rehearse over four days from the first Thursday to the Sunday, with two rehearsal periods allowed for each country. The countries which have already directly qualified for the grand final rehearse on the Monday and Tuesday of Eurovision Week.[41]

After each country has rehearsed, the delegation meets with the show's artistic director in the video viewing room. Here, they watch the footage of the rehearsal just performed, discussing camera angles, lighting and choreography, in order to try to achieve maximum æsthetic effect on television. At this point the Head of Delegation may make known any special requirements needed for the performance, and request them from the host broadcaster. Following this meeting, the delegation hold a press conference where members of the accredited press may pose them questions.[41] The rehearsals and press conferences are held in parallel; so one country holds its press conference, while the next one is in the auditorium rehearsing. A printed summary of the questions and answers which emerge from the press conferences is produced by the host press office, and distributed to journalists' pigeon-holes.[42]

Before each of the semi-finals, one or more full dress rehearsals are held. Since tickets to the live shows are often scarce, tickets are also sold in order that the public may attend these dress rehearsals. Similarly, two or more full dress rehearsals are held after all semi-finals are finished, before the live transmission of the grand final on Saturday evening.[41]

Parties and Euroclub

On the Monday evening of Eurovision Week, a Mayor's Reception is traditionally held, where the city administration hosts a celebration that Eurovision has come to their city. This is usually held in a grand municipally-owned location in the city centre. All delegations are invited, and the party is usually accompanied by live music, complimentary food and drink and—in recent years—fireworks.[43]

After the semi-final and grand final there are after-show parties, held either in a facility in the venue complex or in another suitable location within the city.[44]

A Euroclub is held every night of the week; a Eurovision-themed nightclub, to which all accredited personnel are invited.[45]

During the week many delegations have traditionally hosted their own parties in addition to the officially-sponsored ones. However, in the new millennium the trend has been for the national delegations to centralise their activity and hold their celebrations in the Euroclub.[45]

Voting

The voting systems used in the Contest have changed throughout the years. The modern system has been in place since 1975, and is a positional voting system. Countries award a set of points from 1 to 8, then 10 and finally 12 to other songs in the competition — with the favourite song being awarded 12 points.[46]

Historically, a country's set of votes was decided by an internal jury, but in 1997 five countries (Austria, Switzerland, Germany, Sweden and the United Kingdom) experimented with televoting, giving members of the public in those countries the opportunity to vote en-masse for their favourite songs. The experiment was a success,[47] and from 1998 onwards all countries were encouraged to use televoting wherever possible. Back-up juries are still utilised by each country, in the event of the televoting failure. Nowadays members of the public may also vote by SMS, in addition to televoting.[48]

Presentation of votes

After the interval act is over, when all the points have been calculated, the presenter(s) of the show call upon each voting country in turn to invite them to announce the results of their vote. Prior to 1994 the announcements were made over telephone lines; with the audio being piped into the auditorium for the audience to hear, and over the television transmission. With the advent of more reliable satellite networks, from 1994 onwards voting spokespeople have appeared on camera from their respective countries to read out the votes. Often the opportunity is taken by each country to show their spokesperson standing in front of a backdrop which includes a famous place in that country.

Votes are read out in ascending order, culminating with the maximum 12 points. The scores are repeated by the Contest's presenters in English and French, which has given rise to the famous "douze points" exclamation when the host repeats the top score in French.[33]

From 1957 to 1962, the participating countries were called in reverse order of the presentation of their songs, and from 1963 to 2003, each country was called in the same order in which their song had been presented. Since 2004, the order of the countries' announcements of votes has changed since the inception of the semi-final, and the countries that did not make it to the final each year could also vote. In 2004, the countries were called in alphabetical order (according to their ISO codes).[49] In 2005, the votes from the non-qualifying semi-finalists were announced first, in their running order on the Thursday night; then the finalists gave their votes in their own order of performance. Since 2006, a separate draw has been held to determine the order in which countries would present their votes.[50]

From 1971 to 1973, each country sent two jurors, who were actually present at the Contest venue (though the juries in 1972 were locked away in the Great Hall of Edinburgh Castle) and announced their votes as the camera was trained on them. In 1973 one of the Swiss jurors made a great show of presenting his votes with flamboyant gestures. This system was retired for the next year.[47]

In 1956 no public votes were presented: a closed jury simply announced that Switzerland had won. From 1957 to 1987, the points were displayed on a physical scoreboard to the side of the stage. As digital graphic technology progressed, the physical scoreboards were superseded in 1988 by an electronic representation which could be displayed on the TV screen at the will of the programme's director.[51]

In 2006, the EBU decided to conserve time during the broadcast—much of which had been taken up with the announcement of every single point—because there was an ever-increasing number of countries voting. From then onwards, the points from 1–7 were flashed up onto the screen automatically, and the announcers only read out the 8, 10 and 12 points individually.[50]

The voting is presided over by the EBU scrutineer, who is responsible for ensuring that all points are allocated correctly and in turn. The scrutineer is notified in advance of the results of the last five countries in the running-order of voting, to ensure that no foul play can take place in the form of tactical voting; where for example a country could change its votes after seeing how the trend has gone before them on the scoreboard.[33]

Ties for first place

In 1969, a tie-break system had not yet been conceived, and four countries all tied for first place based on their total numbers of points: France, Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Since there was no predetermined set of rules to decide the winner, all four countries were declared as winners. This caused much discontent among most of the non-winning countries, and mass-walkouts were threatened. Finland, Norway, Sweden and Portugal did not participate in the 1970 Contest as a protest against the results of the previous year. This prompted the EBU to introduce a tie-break rule.[52][53]

In the event of a tie for first place at the end of the evening, a count is made of the total number of countries who awarded any points at all to each of the tied countries; and the one who received points from the most countries is declared the winner. If the numbers are still tied, it is counted how many sets of maximum marks (12 points) each country received. If there is still a tie, the numbers of 10-point scores awarded are compared—and then the numbers of 8-points, all the way down the list. In the extremely unlikely event of there then still being a tie for first place, the song performed earliest in the running order is declared the winner. The same tie-break rule now applies to ties for all places.[54]

As of 2011, the only time since 1969 when two or more countries have tied for first place on total points alone was in 1991, when France and Sweden both totalled 146 points. In 1991 the tie-break rules did not include counting the numbers of countries awarding any points at all to these countries, but began with tallying up the numbers of 12 points awarded. Both France and Sweden had received four sets of 12 points. However, because Sweden had received more sets of 10 points, they were declared the winners. Had the current rule been in play, France would have won instead.[47]

Rules

There are a number of rules which must be observed by the participating nations. The rules are numerous and unabridged, and a separate draft is produced each year, which explicitly specifies the dates by which certain things must be done; for example the deadline by which all the participating broadcasters must submit the final recorded version of their song to the EBU. Many rules pertain to such matters as sponsorship agreements and rights of broadcasters to re-transmit the show within a certain time. The most notable rules which actually affect the format and presentation of the Contest have changed somewhat over the years, and are highlighted here.

Hosting

In 1958 it was decided that from then on, the winning country (France, at the time) would host the Contest the next year.[14] The winner of the 1957 Contest was the Netherlands, and Dutch television accepted the responsibility of hosting in 1958. In all but five of the years since this rule has been in place, the winning country has hosted the show the following year. The exceptions are:

- 1960—hosted by the BBC in London when the Netherlands declined due to expense. The UK was chosen to host because it had come second in 1959.[47]

- 1963—hosted by the BBC in London when France declined due to expense. Although the UK had only come fourth in 1962, Monaco and Luxembourg (who came second and third) had also declined.[47]

- 1972—hosted by the BBC in Edinburgh when Monaco was unable to provide a suitable venue: Monegasque television invited the BBC to take over due to its previous experience.[47]

- 1974—hosted by the BBC in Brighton when Luxembourg declined due to expense. The BBC was becoming known as the host by default, if the winning country declined.[19]

- 1980—hosted by NOS in The Hague when the Israel Broadcasting Authority declined due to expense, and the fact that the date chosen for the Contest (19 April) was Israel's Remembrance Day that year. The Dutch offered to host the Contest after several other broadcasters (including the BBC) were unwilling to do so.[47]

The declinations due to expense were due to those broadcasters' already having hosted the Contest during the past couple of years. Since 1981, all Contests have been held in the country which won the previous year.

Live music

All vocals must be sung live: no voices are permitted on backing tracks.[54] In 1999, the Croatian song featured sounds on their backing track which sounded suspiciously like human voices. The Croatian delegation stated that there were no human voices, but only digitally-synthesised sounds which replicated vocals. The EBU nevertheless decided that they had broken the spirit of the rules, and docked them 33% of their points total that year as used for calculating their five-year points average for future qualification.[55]

From 1956 until 1998, it was necessary for the host country to provide a live orchestra for the use of the participants. Prior to 1973, all music was required to be played by the host orchestra. From 1973 onwards, pre-recorded backing tracks were permitted—although the host country was still obliged to provide a live orchestra in order to give participants a choice. If a backing track was used, then all the instruments heard on the track were required to be present on the stage. In 1997 this requirement was dropped.[47]

In 1999 the rules were amended to abolish the requirement by the host broadcaster to provide a live orchestra, leaving it as an optional contribution.[33] The host that year, Israel's IBA, decided not to use an orchestra in order to save on expenses, and 1999 became the first year in which all of the songs were played as pre-recorded backing tracks (in conjunction with live vocals). The orchestra has not since made an appearance at the Contest; the last time being in 1998 when the BBC hosted the show in Birmingham.

Language

The rule requiring countries to sing in their own national language has been changed several times over the years. From 1956 until 1965, there was no rule restricting the languages in which the songs could be sung. However, in 1966 a rule was imposed stating that the songs must be performed in one of the official languages of the country participating, after Sweden presented its 1965 entry in English.[14]

The language restriction continued until 1973, when it was lifted and performers were again allowed to sing in any language they wished.[56] Several winners in the mid-1970s took advantage of the newly-found allowance, with performers from non-English-speaking countries singing in English, including ABBA in 1974.

In 1977, the EBU decided to revert to the national language restriction. However, special dispensation was given to Germany and Belgium as their national selections had already taken place - both countries' entries were in English.[57]

In 1999, the rule was changed again to allow the choice of language once more.[55] This linguistic allowance led to the Belgian entry in 2003, "Sanomi", being sung in an entirely fictional language.[58] In 2006 the Dutch entry, "Amambanda", was sung partly in English and partly in an artificial language.;[58] and in 2008, the Belgian entry, "O Julissi" was sung in an artificial language.[58]

Broadcasting

Each participating broadcaster is required to broadcast the show in its entirety: including all songs, recap, voting and reprise, skipping only the interval act for advertising breaks if they wish.[54] From 1999 onwards, broadcasters who wished to do so were given the opportunity to take more advertising breaks as short, non-essential hiatuses were introduced into the programme.[33] The Dutch state broadcaster pulled their broadcast of the 2000 final to provide emergency news coverage of a major incident, the Enschede fireworks disaster. This was technically a violation of the rule, but was done out of necessity.

Political recognition issues

In 1978, during the performance of the Israeli entry, the Jordanian broadcaster JRTV suspended the broadcast and showed pictures of flowers. When it became apparent during the later stages of the voting sequence that Israel was going to win the Contest, JRTV abruptly ended the transmission.[47] Afterwards, the Jordanian news media refused to acknowledge the fact that Israel had won and announced that the winner was Belgium (which had actually come 2nd).[59] In 1981 JRTV did not broadcast the voting because the name of Israel appeared on the scoreboard.

In 2005, Lebanon intended to participate in the Contest. However, Lebanese law does not allow recognition of Israel, and consequently Lebanese television did not intend to transmit the Israeli entry. The EBU informed them that such an act would breach the rules of the Contest, and Lebanon was subsequently forced to withdraw from the competition. Their late withdrawal incurred a fine, since they had already confirmed their participation and the deadline had passed.[60]

Other

- In the first Contest in 1956, there was a recommended time limit of 3½ minutes per song.[61] In 1957, despite protests, the Italian song was 5:09 minutes in duration. This led to a stricter time limit of 3 minutes precisely.[62]

- There is no restriction imposed by the EBU on the nationality of the performers or songwriters. Individual broadcasters are, however, permitted to impose their own restrictions at their discretion.[28]

- From 1957 to 1970 (in 1956 there was no restriction at all), only soloists and duos were allowed on stage. From 1963, a chorus of up to three people was permitted. Since 1971, a maximum of six performers have been permitted on the stage.[28]

- The performance and/or lyrics of a song "must not bring the Contest into disrepute".[54]

- Since 1990, all people on stage must be at least 16 years of age.[54]

Expansion of the Contest

The number of countries participating each year has steadily grown over the course of the years, from seven participants in 1956 to over 20 in the late 1980s. In 1993 there were 25 countries participating in the competition, including, for the first time that year, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Slovenia, entering independently due to the dissolution of Yugoslavia.[63]

Because the Contest is a live television programme, a reasonable time limit must be imposed on the duration of the show. In recent years the nominal limit has been three hours, with the broadcast occasionally overrunning.[33]

Pre-selections and relegation

Since 1993, there have been more countries wishing to enter the Contest than there is time to reasonably include all their entries in a single TV show. Several relegation or qualification systems have, therefore, been tried in order to limit the number of countries participating in the competition in any given year. The 1993 Contest introduced two new features: firstly, a pre-selection competition was held in Ljubljana in which seven new countries fought for three places in the international competition. Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, Romania, Slovenia and Slovakia took part in Kvalifikacija za Millstreet; and the three former Yugoslav republics, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Slovenia, qualified for a place in the international final.[64] Also to be introduced that year was relegation. The lowest-placed countries in the 1993 score table were forced to skip the next year, in order to allow the countries which failed the 1993 pre-selection into the 1994 Contest. The 1994 Contest included also—for the first time—Lithuania, Poland and Russia.[65]

Relegation continued through 1994 and 1995;[66] but in 1996 a different pre-selection system was used, in which nearly all the countries participated. Audio tapes of all the songs were sent to juries in each of the countries some weeks before the television show. These juries selected the songs which would then proceed to be included in the international broadcast.[67] Norway, as the host country in 1996 (having won the 1995 Contest), automatically qualified and was therefore excluded from the necessity of going through the pre-selection.

One country which failed to qualify in the 1996 pre-selection was Germany. As one of the largest financial contributors to the EBU, their non-participation in the Contest brought about a funding issue, which the EBU would have to consider.[67]

Big Four

Since 2000, the United Kingdom, Germany, France and Spain have automatically qualified for the Eurovision final, regardless of their positions on the scoreboard in previous Contests.[33] They earned this special status by being the four biggest financial contributors to the EBU (without which the production of the Eurovision Song Contest would not be possible). Due to their untouchable status, these countries became known as the "Big Four".[68] Germany became the first Big Four country to win the Eurovision Song Contest since the rule was made in 2000; this occurred when Lena Meyer-Landrut won the 2010 Eurovision Song Contest.

Italy also contribute heavily to the EBU and they have been offered similar status should they wish to rejoin the Eurovision Song Contest. This would obviously make them known as the "Big Five", however they have currently not shown any interest in returning despite attempts to encourage them.

Qualification

From 1997 to 2001, countries qualified for each Contest based on the average of their points totals for their entries over the previous five years.[69][70] However, there was much discontent voiced over this system because a country could be punished by not being allowed to enter merely because of poor previous results, which did not take into account how good a fresh attempt might be. This led the EBU to create what was hoped would be a more permanent solution to the problem, which was to have two shows every year: a qualification round, and the grand final. In these two shows there would be enough broadcast time to include all the countries which wished to participate, every year. The qualification round became known as the Eurovision Semi-Final. In 2008 due to the number of nations entering, it changed very slightly as two separate semi finals were created, once going from the first semi a nation would enter straight into the final as would those progressing from the second semi.[71]

Semi-finals

A qualification round, known as the semi-final, was introduced for the 2004 Contest.[72] This semi-final was held on the Wednesday during Eurovision Week, and was a programme similar in format to the grand final, whose time slot remained 19:00 UTC on the Saturday. The highest-placed songs from the semi-final would qualify for the grand final, while the lower-placed songs were out of the competition for that year. From 2005–2007, the semi-final programme was held on the Thursday of Eurovision Week.[73]

The ten most highly-placed non-Big Four countries in the grand final were guaranteed a place in the following year's grand final, without the need to participate in next year's semi. If, for example, Germany came in the top ten, the eleventh-placed non-Big-Four country would automatically qualify for the next year's grand final.[28] The remaining countries—which had not automatically qualified for the grand final—had to enter the semi.[28]

At the 50th annual meeting of the EBU reference group in September 2007, it was decided that from the 2008 Contest onwards there would be held two semi-finals.[74] From 2008 onwards, the scoreboard position of any previous years has not been relevant, and—save for the automatic qualifiers—all participating countries have had to participate in the semi-finals, regardless of their previous year's scoreboard position. The only countries which automatically qualify for the grand final are the host country, and the Big Four: France, Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom, who continue to enjoy their protected status.[54]

In each of the semi-finals the voting is conducted among those countries which participate in that semi-final in question. With regards to the automatic grand final qualifiers, which do not participate in the semi-finals, a draw is conducted to determine in which semi-final each of them will be allowed to vote. In contrast, every participating country in a particular year may vote in the Saturday grand final — whether their song qualified from the semi or not.[75]

After the votes have been cast in each semi-final, the countries which received the most votes—and will therefore proceed to the grand final on Saturday—are announced by name by the presenters. Full voting results are withheld until after the grand final, whereupon they are published on the EBU's website.[54]

Winners

Winning the Eurovision Song Contest provides a unique opportunity for the winning artist(s) to capitalise on the surrounding publicity to further his, her or their career(s).

Artists

The most notable winning Eurovision artist whose career was directly launched into the spotlight following their win was ABBA, who won the Contest for Sweden in 1974 with their song "Waterloo". ABBA went on to become one of the most successful bands of all time.[76]

Another notable winner who subsequently achieved international fame and success was French Canadian singer, Céline Dion, who won the Contest for Switzerland in 1988 with the song "Ne partez pas sans moi", which subsequently helped launch her international career.[77]

Other artists who have achieved varying degrees of success after winning the Contest include France Gall ("Poupée de cire, poupée de son", Luxembourg 1965), Dana ("All Kinds of Everything", Ireland 1970), Vicky Leandros ("Après toi", Luxembourg 1972), Brotherhood of Man ("Save Your Kisses for Me", United Kingdom 1976), Marie Myriam ("L'oiseau et l'enfant", France 1977), Johnny Logan (who won twice for Ireland; with "What's Another Year?" in 1980, and "Hold Me Now" in 1987), Bucks Fizz ("Making Your Mind Up", United Kingdom 1981), Nicole ("Ein Bißchen Frieden", Germany 1982), and Herreys ("Diggi-Loo Diggi-Ley", Sweden 1984). Many other winners include well-known artists who won the Contest mid-career, after they had already established themselves as successful. An example is Katrina and the Waves, representing the United Kingdom, who were the winners of the contest with the song, Love Shine a Light.[78]

Some artists, however, have vanished into relative obscurity, making little or no impact on the international music scene after their win.

Countries

Ireland holds the record for the most number of wins, having won the Contest seven times—including three times in a row in 1992, 1993 and 1994. France, Luxembourg and United Kingdom are joint second with five wins.[79]

The early years of the Contest saw many wins for "traditional" Eurovision countries: France, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. However, the success of these countries has declined in recent decades: the Netherlands last won in 1975; France in 1977; and Luxembourg in 1983. The last time Luxembourg entered the Contest was in 1993.[80]

The first years of the 21st century produced a spate of first-time winners, from both "new" Eurovision countries, and old-timers who had entered for many years without a win. Every year from 2001 to 2008 resulted in a country winning for the first time. The 2006 winner was Finland, which finally won after having entered the Contest for 45 years. Ukraine on the other hand did not have to wait so long, winning with their second entry in 2004. Serbia won the very first year it entered as an independent state, in 2007.[81]

Criticisms and controversy

The Contest has been the subject of criticism regarding both its musical content and the perception that it is more about politics than it is about music.[82][83]

Musical style and presentation

Because the musical songs are playing to such a diverse international audience with contrasting musical tastes, and that countries want to be able to appeal to as many people as possible to gain votes, the majority of the songs have historically been middle-of-the-road pop. Deviations from this formula have rarely achieved success, leading to the Contest gaining a reputation for its music being "bubblegum pop".[84] This well-established pattern, however, was notably broken in 2006 with Finnish hard rock band Lordi's landslide victory. As Eurovision is a visual show, many performances attempt to attract the attention of the voters through means other than the music, sometimes leading to bizarre on-stage theatrics and costumes, including the use of revealing dress.[85]

Political and national voting

The Contest has long been accused of political bias, where the perception is that judges—and now televoters—allocate points based on their nation's relationship to the other countries, rather than the musical merits of the songs.[86] According to one study of Eurovision voting patterns, certain countries tend to form "clusters" or "cliques" by frequently voting in the same way.[87] On the other hand, however, scholars argue that certain countries allocate disproportionately high points to others because of similar musical tastes, cultures and because they speak similar languages,[88][89] and are therefore more likely to appreciate each other's music; for example, the explanation for Greece and Cyprus' routine exchange of 12 points in every possible occasion since popular voting was introduced in 1998 is because those countries share the same music industry and language, and artists who are popular in one country are popular in the other.

Another influential factor is the high proportion of expatriates, ethnic minorities and diaspora living in certain countries, often due to recent political upheaval. Although judges and televoters cannot vote for their own country's entry, expatriates and diaspora can vote for their country of origin from their current location. The "émigré vote" is seen as an important factor for Turkey, as their song often garners a large proportion of the votes from countries where there is a sizeable diaspora, such as Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, France and Austria.[90]

Since the number of points to be distributed allotted to each country remains equal, and independent of their population, voters in countries with larger populations have less power as individuals to influence the result of the Contest than those voting from countries with smaller populations.

In a move to help reduce the effects of voting blocs since the advent of televoting in the Eurovision Song Contest, the 2009 edition re-introduced national juries alongside televoting in the final, both contributing to 50% of the vote.[91] This hybrid system was implemented in semi-finals for 2010.[92]

Spin-offs

A number of spin-offs and imitators of the Eurovision Song Contest have been produced over the years:

- Our Sound—Asia-Pacific version.

- Junior Eurovision Song Contest—held annually since 2003, for artists under the age of 16.

- MGP Nordic—Nordic contest similar to the Junior Eurovision Song Contest.

- Sopot International Song Festival—held in Sopot, Poland, annually since 1961.

- Intervision Song Contest—held by the Eastern bloc countries between 1977 and 1980.

- World Oriental Music Festival—first held in Sarajevo in 2005; includes participants from Europe and Asia.

- Bundesvision Song Contest—held annually between the 16 states of Germany since 2005.

- Baltic Song Contest—held annually in Karlshamn, Sweden.

- Castlebar Song Contest—held annually in Castlebar, County Mayo, Ireland between 1966 and 1989.

In Autumn 2005, the EBU organised a special programme to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Contest. The show, entitled Congratulations (after Cliff Richard's entry for the United Kingdom in 1968) was held in Copenhagen, and featured many artists from the last 50 years of the Contest. A telephone vote was held to determine the most popular Eurovision song of all-time, which was won by ABBA's "Waterloo" (winner, Sweden 1974).[93]

See also

- List of Eurovision Song Contest winners

- Best of Eurovision

- European music

Notes

- ↑ "Winners of the Eurovision Song Contest" (PDF). European Broadcasting Union. http://www.ebu.ch/departments/television/pdf/Winners-Palmares_56-02.pdf. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

- ↑ "Live Webcast". European Broadcasting Union. http://web.archive.org/web/20060525094524/http://www.eurovision.tv/english/2513.htm. Retrieved 2006-05-25.

- ↑ Staff (2006-05-21). "Finland wins Eurovision contest". Al Jazeera English. http://english.aljazeera.net/archive/2006/05/2008410141723346664.html. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- ↑ Murray, Matthew. "Eurovision Song Contest - International Music Program". Museum of Broadcast Communications. http://www.museum.tv/archives/etv/E/htmlE/eurovisionso/eurovisionso.htm. Retrieved 2006-07-15.

- ↑ "Eurovision Trivia" (PDF). BBC Online. 2002. http://www.bbc.co.uk/pressoffice/pressreleases/stories/2002/05_may/16/eurovision_trivia.pdf. Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 1972". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=288. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 2004 Final". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=8. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- ↑ Philip Laven (July 2002). "Webcasting and the Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.ebu.ch/en/technical/trev/trev_291-editorial.html. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ↑ "Eurovision song contest 2006 - live streaming". Octoshape. 2006-06-08. http://www.streamingmedia.com/press/view.asp?id=4907. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Staff (2005-05-17). "Singing out loud and proud". Bristol Evening Post (Daily Mail and General Trust). "In the mid-1950s, the members of the European Broadcasting Union set up an ad-hoc committee to investigate ways of rallying the countries of Europe round a light entertainment programme. At Monaco, in late January 1955, this committee, chaired by Marcel Bezencon, director general of Swiss Television, came up with the idea of creating a song contest, inspired by the very popular San Remo Festival. The idea was approved by the EBU General Assembly in Rome on October 19, 1955, and it was decided that the first "Eurovision Grand Prix" - so baptised, incidentally, by a British journalist - would take place in spring 1956 at Lugano, Switzerland."

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Jaquin, Patrick (2004-12-01). "Eurovision's Golden Jubilee". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.ebu.ch/en/union/diffusion_on_line/television/tcm_6-8971.php. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ "History of Eurovision". BBC Online. 2003. http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio2/eurovision/2003/history. Retrieved 2006-07-20.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Waters, George T. (Winter 1994). "Eurovision: 40 years of network development, four decades of service to broadcasters". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.ebu.ch/en/technical/trev/trev_262-editorial.html. Retrieved 2006-07-15.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 "Historical Milestones". European Broadcasting Union. 2005. http://web.archive.org/web/20060526065558/http://www.eurovision.tv/english/611.htm. Retrieved 2006-05-26.

- ↑ Thomas, Franck (1999). "Histoire 1956 à 1959". eurovision-fr.net. http://web.archive.org/web/20060502192602/http://www.eurovision-fr.net/histoire/histoire5659.php. Retrieved 2006-07-17. (French)

- ↑ "The EBU Operations Department". European Broadcasting Union. 2005-06-14. http://www.ebu.ch/departments/operations/ops.php. Retrieved 2006-07-20.

- ↑ "Voting fault hits Eurovision heat". BBC News. 2004-05-13. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/3712029.stm. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ↑ http://www.eurovision.tv/upload/esc2009rules.pdf

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Eurovision Song Contest 1974". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=290. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ↑ Barnes, Clive. "Riverdance Ten Years on". RiverDance. http://www.riverdance.com/htm/theshow/thejourney. Retrieved 2006-07-27.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 1956". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=273. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 1979". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=295. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Membership conditions". European Broadcasting Union. 2006-02-22. http://www.ebu.ch/departments/legal/activities/leg_membership.php. Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- ↑ "Extracts From The Radio Regulations" (PDF). International Telecommunication Union. 1994. http://www.ebu.ch/CMSimages/en/leg_ref_itu_radio_regulations_tcm6-4307.pdf. Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- ↑ "Radio Regulations". International Telecommunication Union. 2005-09-08. http://life.itu.int/radioclub/rr/art05.htm#Reg. Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- ↑ http://www.esctoday.com/news/read/12068?rss

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest: History". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 "Rules of the 2005 Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. 2005. http://web.archive.org/web/20060210010517/http://www.eurovision.tv/searchfiles_english/574.htm. Retrieved 2006-02-10.

- ↑ "Row prompts Eurovision withdrawal". BBC News. 2006-03-20. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4824692.stm. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ↑ http://www.star-ecentral.com/news/story.asp?file=/2005/5/19/music/10979477&sec=music

- ↑ Schacht, Andreas (2008-11-13). "SVT to present first 8 artists". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/news?id=1475. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ "Operación Triunfo: Un intenso camino hacia el festival de eurovision" (in Spanish). Terra Networks. http://www.portalmix.com/operaciontriunfo1/eurovision. Retrieved 2006-07-22.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 "Rules of the 44th Eurovision Song Contest, 1999" (PDF). European Broadcasting Union. 1998-10-13. http://www.eurosong.net/archive/esc1999.pdf. Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- ↑ Fawkes, Helen (2005-05-19). "Ukrainian hosts' high hopes for Eurovision". BBC News Online. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/music/4561275.stm. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ↑ "General Information on Millstreet" (PDF). Republic of Ireland. http://www.ria.gov.ie/filestore/publications/English-CORK-_Millstreet-FINALISED.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- ↑ "Green Glens Arena". Town of Millstreet. http://www.millstreet.ie/green%20glens/greenglens.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ↑ "Reference group meets in Moscow". European Broadcasting Union. 2008-09-12. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/news?id=1361. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ Marone, John. "Where Do We Put The Foreign Tourists?". The Ukrainian Observer. http://web.archive.org/web/20060204201731/http://www.ukraine-observer.com/articles/208/655. Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- ↑ "Serbia in spotlight for Eurovision". BBC News. 2008-05-23. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/7418045.stm. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ↑ "Belgrade 2008". European Broadcasting Union. 2008-03-17. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/news/belgrade-2008?id=587. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 "Rehearsal Schedule" (PDF). European Broadcasting Union. 2008. http://www.eurovision.tv/upload/media/ESC2008_rehearsals.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ↑ "Interviews 2008". European Broadcasting Union. 2008. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/interviews-2008?id=944. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ↑ "The grand opening reception!". European Broadcasting Union. 2009-05-11. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/news?id=2560. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ↑ "After Show Party: Reactions". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/news?id=2793. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "The EuroClub: Official party venue opened its doors". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/news?id=2309. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 1975". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=291. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 47.4 47.5 47.6 47.7 47.8 O'Connor, John Kennedy (2005). The Eurovision Song Contest 50 Years The Official History. London: Carlton Books Limited. ISBN 1-84442-586-X.

- ↑ http://english.people.com.cn/200705/11/eng20070511_373758.html

- ↑ "Eurovision 2004 - Voting Briefing". European Broadcasting Union. 2004-05-12. http://web.archive.org/web/20050507155415/http://www.eurovision.tv/archive_2004/english/1098.htm. Retrieved 2005-05-07.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 "Results from the draw". European Broadcasting Union. 2006-03-21. http://web.archive.org/web/20060527003915/http://www.eurovision.tv/english/2038.htm. Retrieved 2006-05-27.

- ↑ "A to Z of Eurovision". BBC Online. http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio2/eurovision/mymu/atoz.shtml. Retrieved 2006-08-09.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 1969". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=286. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 1970". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=223. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 54.4 54.5 54.6 "Rules for the Eurovision Song Contest 2009" (PDF). European Broadcasting Union. http://eurovision.tv/upload/esc2009rules.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 "Eurovision Song Contest 1999". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=314. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 1973". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=289. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 1977". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=293. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 Schacht, Andreas (2008-03-09). "Ishtar for Belgium to Belgrade!". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/news?id=554. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 1978". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=294. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ "Lebanon withdraws from Eurovision". BBC News Online. 2005-03-18. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4362373.stm. Retrieved 2006-07-15.

- ↑ "Reglement du Grand Prix Eurovision 1956 De La Chanson Européenne" (PDF). European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/upload/history/1956/56_rules.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 1957". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=274. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 1993". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=235. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 1993". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=235. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 1994". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=309. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 1995". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=310. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 "Eurovision Song Contest 1996". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=311. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ http://www.ctv.ca/servlet/ArticleNews/story/CTVNews/20090515/eurovision_contest_090516/20090516?hub=TopStories

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 1997". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=312. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 2001". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=266. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ↑ "Bubble rapt". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2004-05-17. http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2004/05/16/1084646073107.html.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 2004 Semi-Final". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=9. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest 2005 Semi-Final". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/history/by-year/contest?event=157. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- ↑ "Eurovision Song Contest - Two Semi Finals In 2008" (PDF). European Broadcasting Union. 2007-10-01. http://www.ebu.ch/CMSimages/en/PR_ESC%20Semi-Finals_01%2E10%2E07_EN_tcm6-54154.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ "The voting". European Broadcasting Union. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/moscow2009/voting. Retrieved 2009-25-25.

- ↑ "Opening of Sweden's ABBA museum is delayed". The San Francisco Chronicle. 2008-09-12. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2008/09/12/DDBN12SDVQ.DTL.

- ↑ "Serbia's "Prayer" wins Eurovision Song Contest". Reuters. 2007-05-14. http://www.reuters.com/article/entertainmentNews/idUSSCH28177920070514.

- ↑ Gray, Sadie (2008-10-19). "Lloyd Webber agrees to try to write a winner for Eurovision". The Independent (London). http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/news/lloyd-webber-agrees-to-try-to-write-a-winner-for-eurovision-966380.html. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ↑ Sharrock, David (1999-05-29). "Discord at pop's Tower of Babel". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/1999/may/29/davidsharrock?gusrc=rss&feed=music. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ↑ http://www.esctoday.com/news/read/3221

- ↑ http://www.b92.net/eng/news/society-article.php?yyyy=2007&mm=05&dd=13&nav_category=113&nav_id=41193

- ↑ "Politics 'not Eurovision factor'". BBC News Online. 2007-05-09. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/berkshire/6640231.stm. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ↑ "Malta slates Eurovision's voting". BBC News Online. 2007-05-14. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/6654719.stm. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ↑ "Edinburgh Fringe show celebrates Eurovision kitsch". Reuters. 2007-08-11. http://uk.reuters.com/article/idUKL1142844820070814. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ See Paul Allatson, “‘Antes cursi que sencilla’: Eurovision Song Contests and the Kitsch Drive to Euro-Unity,” in the Special issue on Creolisation: Towards a Non-Eurocentric Europe, in Culture, Theory and Critique [1], vol. 48, no. 1 (Spring 2007): 87–98.

- ↑ "Eurovision votes 'farce' attack". BBC News Online. 2004-05-16. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/wales/south_east/3719157.stm. Retrieved 2006-07-15.

- ↑ Daniel Fenn, Omer Suleman, Janet Efstathiou & Neil F. Johnson, Oxford University (2006-05-22). "Connections, cliques and compatibility between countries in the Eurovision Song Contest". arxiv.org. http://arxiv.org/abs/physics/0505071v1. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- ↑ Ginsburgh, Victor and Abdul Noury. 2006. The Eurovision Song Contest Is Voting Political or Cultural?

- ↑ Spierdjik, Laura; Vellekoop, Michel (2006-05-18). "Geography, Culture, and Religion: Explaining the Bias in Eurovision Song Contest Voting" (PDF). rug.nl. http://www.rug.nl/economie/faculteit/medewerkers/SpierdijkL/eurovision.pdf?as=pdf. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ↑ Gatherer, Derek (2006-03-31). "Comparison of Eurovision Song Contest Simulation with Actual Results Reveals Shifting Patterns of Collusive Voting Alliances". Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation (Guildford: SimSoc Consortium) 9 (2): 1. ISSN 1460-7425. http://jasss.soc.surrey.ac.uk/9/2/1.html. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- ↑ Viniker, Barry (2008-12-08). "EBU confirms 50/50 vote for Eurovision Song Contest". ESCToday. http://esctoday.com/news/read/12655. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

- ↑ Bakker, Sietse (2009-12-31). "Exclusive: 39 countries to be represented in Oslo". EBU. http://www.eurovision.tv/page/news?id=7923&_t=Exclusive%3A+39+countries+to+be+represented+in+Oslo. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- ↑ "Abba win 'Eurovision 50th' vote". BBC News Online. 2005-10-23. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/music/4366574.stm. Retrieved 2006-07-20.

External links

- Eurovision Song Contest official web site

- Eurvision Song Contest official youtube channel

Critical studies

- Allatson, P. (2007) “‘Antes cursi que sencilla’: Eurovision Song Contests and the Kitsch Drive to Euro-Unity,” in the Special issue on Creolisation: Towards a Non-Eurocentric Europe, in Culture, Theory and Critique, vol. 48, no. 1 (Spring 2007): 87–98.

- Fenn D; et al. ( 2005.). How does Europe make its mind up? Connections, cliques, and compatibility between countries in the Eurovision Song Contest. arXiv:physics/0505071

- Gatherer, D. (2006). Comparison of Eurovision Song Contest Simulation with Actual Results Reveals Shifting Patterns of Collusive Voting Alliances, Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation vol. 9, no. 2.

- Raykoff, Ivan and Robert D. Tobin (eds.), A Song for Europe: Popular Music and Politics in the Eurovision Song Contest (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2007).

- Yair, G; (1995). 'Unite Unite Europe' The political and cultural structures of Europe as reflected in the Eurovision Song Contest, Social Networks. 17: 147–161.

- Yair and Maman (1996). The Persistent Structure of Hegemony in the Eurovision Song Contest, Acta Sociologica. 39: 309–325

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||