European Union law

| European Union |

This article is part of the series: |

|

Policies and issues

|

|

Foreign relations

|

|

Law

|

European Union law (historically called European Community law) is a body of treaties, law and court judgements which operates alongside the legal systems of the European Union's member states. It has direct effect[1] within the EU's member states and, where conflict occurs, takes precedence over national law.[2]

The primary source of EU law is the EU's treaties. These are power-giving treaties which set broad policy goals and establish institutions that, amongst other things, can enact legislation in order to achieve those goals. The legislative acts of the EU come in two forms: regulations and directives. Regulations become law in all member states the moment they come into force, without the requirement for any implementing measures,[3] and automatically override conflicting domestic provisions.[4] Directives require member states to achieve a certain result while leaving them discretion as to how to achieve the result. The details of how they are to be implemented are left to member states.[5]

EU legislation derives from decisions taken at the EU level, yet implementation largely occurs at a national level. The principle of uniformity is therefore a central theme in all decisions by the European Court of Justice, which aims to ensure the application and interpretation of EU laws does not differ between member states.

Contents |

History and development

The development of law of the European Community has been largely moulded by the European Court of Justice (ECJ). In the landmark case of Van Gend en Loos in 1963, the ECJ ruled that the European Community, through the will of Member States expressed in the Treaty of Rome, "constitutes a new legal order of international law for the benefit of which the states have limited their sovereign rights albeit within limited fields."

The distinction between European Community (EC) law and European Union law is that based on the Treaty structure of the European Union. The European Community constitutes one of the 'three pillars' of the European Union and concerns the social and economic foundations of the single market. The second and the third pillars were created by the Treaty on European Union (the Maastricht Treaty) and involve Common Security and Defence Policy and Internal Security. Decision-making under the second and third pillars is not subject to majority voting at present. The Maastricht Treaty created the Justice and Home Affairs pillar as the third pillar. Subsequently, the Treaty of Amsterdam transferred the areas of illegal immigration, visas, asylum, and judicial co-operation to the European Community (the first pillar). Now Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters is the third pillar. Justice and Home Affairs now refers both to the fields that have been transferred to the EC and the third pillar.

Several principles such as subsidiarity, proportionality, the principle of conferral, and the principle of legal certainty have become prominent in the development of European Union law. Scholars such as Catherine Barnard argue that the Four Freedoms form the substantive law of the EU: free movement of goods, services, capital, and labour within the internal market of the EU.

Sources of law

| Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Consolidated version of the Treaty on European Union

Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

|

Treaties

The primary legislation, or treaties, are effectively the constitutional law of the European Union. They are created by governments from all EU Member States acting by consensus. They lay down the basic policies of the Union, establish its institutional structure, legislative procedures, and the powers of the Union. The Treaties that make up the primary legislation include:

|

|

The various annexes and protocols attached to these Treaties are also considered a source of primary legislation.

Legislation

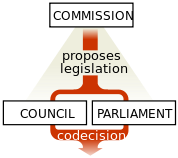

The treaties allow for the adoption of legislation and other legal acts so as to allow the EU to pursue the objective set out in the treaties. The treaties haven't, however, established any single body as a legislature. Instead legislative power is spread out among the Institutions of the European Union, although the principle actors are the Council of the European Union (or Council of Ministers), the European Parliament and the European Commission.

The relative power of a particular institution in the legislative process depends on the legislative procedure used, which in turn depends on the policy area to which the proposed legislation is concerned. In some areas, they participate equally in the making of EU law, in others the system is dominated by the Council. Which areas are subject to which procedure is laid down in the treaties of the European Union. All EU legislation must be based on a specific Treaty article, which is referred to as its legal basis.

Union legislation falls into two types: directives and regulations. Directives set (sometimes quite specific) objectives but leave the implementation to the EU's member states. Regulations are directly applicable to member states and take effect without the need to implementing measures. Other legal acts include decisions and recommendations and opinions.

Court decisions

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) has long played a pivotal role in the development of EU law, principally through the enunciation of legal principles such as direct effect and supremacy.

The European Court of Justice (ECJ), has jurisdiction in various specific matters, conferred on it by the Treaties. In particular Article 220 EC charges the ECJ (and the Court of First Instance) with ensuring that the law is observed "in the interpretation and application of this Treaty",[6] and this provision has been used by the Court to extend its powers beyond those otherwise expressly granted.[7] Since the Maastricht Treaty, the Court has been empowered to impose pecuniary penalties on Member States who disobey.[8] The Court has been instrumental in shaping law in the EU, and its approach is generally described as purposive or teleological[9] The jurisprudence of the Court, together with that of the courts of the member states, has established and defined a number of principles of European Union law, which bind EU institutions and member states, including direct effect, the supremacy of European Union law over that of Member states, and state liability for damages.[9]

According to the Treaty, the Court comprises one judge per member state; as of 2007 it has 27 judges. The judges are appointed "by common accord of the Governments of the Member states".[10] The judges are appointed for a (renewable) period of six years.[10] The Court is assisted by eight Advocates General.[11] The Court usually sits in Chambers of three or five, but in some cases as a single judge, in especially important cases as a Grand Chamber of thirteen judges or as a full court.[12][13]

The General Court (formerly called The Court of First Instance(CFI) prior to the coming into force of The Lisbon Treaty was established on the basis of the Single European Act in 1988 and was originally "attached to" the ECJ in a subsidiary role. Following the Treaty of Nice it was given greater independence and its own jurisdiction.[14] The jurisdiction of the General Court includes direct actions by natural or legal persons against Community institutions for their acts (or failure to act), actions by Member states against the Commission, and actions relating to Community trade marks.[15]

According to the Treaty, the court comprises at least one judge per member state; as of 2007 it has 27 judges. The judges are appointed for a (renewable) period of six years.[15] Like the ECJ, the CFI usually sits in Chambers of three or five, but in some cases as a single judge, as a Grand Chamber of thirteen judges, or as a full court.[15] Decisions of the CTI can be appealed to the ECJ on matters of law.[14] To reduce the workload of the ECJ and the CFI, the Treaty of Nice (Article 225a) introduced "judicial panels" to be used in some areas, with appeal to the CFI.[16]

Legal principles

Supremacy

It has been ruled many times by the European Court of Justice that EC (European Community-first pillar) law is superior to national laws. Where a conflict arises between EC law and the law of a Member State, EC law takes precedence, so that the law of a Member State must be disapplied. This doctrine, known as the supremacy of EC law, emerged from the European Court of Justice in Costa v ENEL.[17] Mr Costa was an Italian citizen opposed to nationalising the Italian energy company ENEL, because he had shares in it. He refused to pay his electricity bill in protest, and argued that nationalisation infringed EC law on the State distorting the market.[18] The Italian government believed that this was not even an issue that could be complained about by a private individual, since it was a national law decision to make. The Court ruled in favour of the government, because the relevant Treaty rule on an undistorted market was one on which the Commission alone could challenge the Italian government. As an individual, Mr Costa had no standing to challenge the decision, because that Treaty provision had no direct effect.[19] But on the logically prior issue of Mr Costa's ability to raise a point of EC law against a national government in legal proceeding before the courts in that Member State the ECJ disagreed with the Italian government. It ruled that EC law would not be effective if Mr Costa could not challenge national law on the basis of its alleged incompatibility with EC law.

It follows from all these observations that the law stemming from the treaty, an independent source of law, could not, because of its special and original nature, be overridden by domestic legal provisions, however framed, without being deprived of its character as community law and without the legal basis of the community itself being called into question.[20]

However, while Community law is accepted as taking precedence to the law of Member States, not all Member States share the analysis used by the European institutions about why EC law overrides national law, when a conflict appears.[21]

Many countries' highest courts have stated that Community law takes precedence provided that it continues to respect fundamental constitutional principles of the Member State, the ultimate judge of which will be the Member State (more exactly, the court of that Member State), rather than the European Union institutions themselves.[22] This reflects the idea that Member States remain the "Master of the Treaties", and the basis for EC law's effect. In other cases, countries write the precedence of Community law into their constitutions. For example, the Constitution of Ireland contains a clause that, '"No provision of this Constitution invalidates laws enacted, acts done or measures adopted by the State which are necessitated by the obligations of membership of the European Union or of the Communities..."

However, the difference of positions remained of solely academic importance. As of now, no court of any Member State has ever challenged the validity of any legal act of the European Union by any other means than referring the question to the European Court of Justice. The German legislature even accepted the judgment of the European Court of Justice in the case of Tanja Kreil, which rendered void a provision in the German constitution barring women from voluntary service in the armed forces, subsequently amended the constitution and accepted women for any position in the forces.

Direct effect

EU law covers a broad range which is comparable to that of the legal systems of the Member States themselves.[23] Both the provisions of the Treaties, and EU regulations are said to have "direct effect" horizontally. This means private citizens can rely on the rights granted to them (and the duties created for them) against one another. For instance, an air hostess could sue her airline employer for sexual discrimination.[24] The other main legal instrument of the EU, "directives", have direct effect, but only "vertically". Private citizens may not sue one another on the basis of an EU directive, since these are addressed to the Member States. Directives allow some choice for Member States in the way they translate (or 'transpose') a directive into national law - usually this is done by passing one or more legislative acts, such as an Act of Parliament or statutory instrument in the UK. Once this has happened citizens may rely on the law that has been implemented. They may only sue the government "vertically" for failing to implement a directive correctly. An example of a directive is the Product liability Directive,[25] which makes companies liable for dangerous and defective products that harm consumers.

Fundamental rights

The EU Treaties did not originally include any reference to fundamental or human rights. In 1964 the European Court of Justice handed down its decision in Costa v ENEL, in which the Court decided that Community law should take precedence over conflicting national law. This meant that national government could not escape what they had agreed to at a European level by enacting conflicting domestic measures, but it also potentially meant that the EEC legislator could legislate unhindered by the restrictions imposed by fundamental rights provisions enshrined in the constitutions of member states. This issue came to a head in 1970 in the case of Handelsgesellschaft case when a German court ruled that a piece of EEC legislation infringed the German Basic Law. On a reference from the German court, the ECJ ruled that whilst the application of Community law could not depend on its consistency with national constitutions, fundamental rights did form part an "integral part of the general principles of [European Community] law" and that inconsistency with fundamental right could form the basis of a successful challenge to a European law.[26]

In ruling as it did in Handelsgesellschaft the ECJ had, in effect, created a doctrine of unwritten rights which bound the Community institutions. While the court's fundamental rights jurisprudence was approved by the institutions in 1977[27] and a statement to that effect by inserted into the treaties by the Maastricht Treaty,[28] it was only in 1999 that the European Council formally went about the process of initiating the drafting of a codified catalogue of fundamental rights for the EU.

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union now enshrines certain political, social, and economic rights for European Union citizens and residents, into European Union law. It was drafted and officially proclaimed in 2000, but its legal status was then uncertain and it did not have full legal effect[29] until the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon on 1 December 2009. In 2007 a Fundamental Rights Agency was created by revising the mandate of an existing monitoring centre.

Under the Charter the European Union (EU) must act and legislate consistently with the Charter and the EU's courts will strike down EU legislation which contravenes it. The Charter only applies to member states when they are implementing EU law and does not extend the competences of the EU beyond the competences given to it elsewhere in the treaties.

Social chapter

The Social chapter in the European Union refers to parts of the treaty which deal with the equal treatment of men and women under Article 8 TFEU and the regulation of working time under the Working Time Directive. One recent piece of anti-discrimination legislation is Directive 2006/54/EC "on the implementation of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women in matters of employment and occupation".

The UK secured an opt-out from the Social Chapter as many members of John Major’s government were fundamentally opposed to extension of the EU’s competence into social areas. The issue was so divisive that it threatened to split the Cabinet. The Labour Party abolished this opt-out immediately after coming to power in the 1997 general election.[30]

- Defrenne v Sabena (No 2)

- Foster v British Gas plc

- C-170/84 Bilka-Kaufhaus Gmbh v Karin von Weber [1986] ECR 1607 - on the interpretation of "objective justification" for indirect discrimination between men and women, under Article 141 TEC

Four freedoms

The core of European Union economic and social policy is summed up under the idea of the four freedoms - free movement of goods, capital, services and persons. Sometimes, they are also counted up as five freedoms, namely the free movement of goods, capital, services, workers and the freedom of establishment, but the difference is merely in denomination, they both refer to the same areas of substantive law.

Movement of goods

Under the first title of the Treaty of the European Communities one finds the provisions dealing with the free movement of goods. In the years between the two world wars, and leading into the Great Depression, governments around the world had employed vigorous policies of national protectionism. The erection of tariffs and customs duties on imports and sometimes the export of goods was widely seen as contributing to a fall in trade and hence the stalling of economic growth and development. Economists had long said, since Adam Smith and David Ricardo that the Wealth of Nations could only be strengthened by the long term lowering and abolition of barriers and costs to international trade. The abolition of all such barriers is the function of the treaty provisions. According to Article 28 EC,

"28. Quantitative restrictions on imports and all measures having equivalent effect shall be prohibited between Member States."

Article 29 EC states the same for exports. The first thing to note is that the prohibition is simply between member states of the European Community. One of the institutions' primary duties is the management of trade policy to third parties - other countries such as the United States, or China. For instance, the controversial Common Agricultural Policy is regulated under Title II EC, Article 34(1) authorising "compulsory coordination of national market organisations" with common European organisation. The second thing to note is that Article 30 sets out the exceptions to the prohibition on free movement of goods.

"30. The provisions of Articles 28 and 29 shall not preclude prohibitions or restrictions on imports, exports or goods in transit justified on grounds of public morality, public policy or public security; the protection of health and life of humans, animals or plants; the protection of national treasures possessing artistic, historic or archaeological value; or the protection of industrial and commercial property. Such prohibitions or restrictions shall not, however, constitute a means of arbitrary discrimination or a disguised restriction on trade between Member States."

So governments of member states may still justify certain trade barriers when public morality, policy, security, health, culture or industrial and commercial property might be threatened by complete abolition. One recent example of this was that during the mad cow disease crisis in the United Kingdom, France erected a barrier to imports of British beef.[31]

Movement of workers

Movement of capital

Freedom of establishment

Competition law

Since the goal of the Treaty of Rome was to create a common market, and the Single European Act to create an internal market, it was crucial to ensure that the efforts of government could not be distorted by corporations abusing their market power. Hence under the treaties are provisions to ensure that free competition prevails, rather than cartels and monopolies sharing out markets and fixing prices. Competition law in the European Union is largely similar and inspired by United States antitrust.

Collusion and cartels

The Treaty of the European Communities (TEC), under Article 81 (1), prohibits

"all agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which may affect trade between member states and which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the common market."

Agreements, decisions and concerted practices, known collectively as "collusion" are deemed automatically void under Article 81 (2). Article 81 (3), however, makes exceptions for collusion that could be of economic benefit.

"The provisions of paragraph 1 may, however, be declared inapplicable in the case of (i) any agreement or category of agreements between undertakings; (ii) any decision or category of decisions by associations of undertakings; (iii) any concerted practice or category of concerted practices, which contributes to improving the production or distribution of goods or to promoting technical or economic progress, while allowing consumers a fair share of the resulting benefit, and which does not (a) impose on the undertakings concerned restrictions which are not indispensable to the attainment of these objectives; (b) afford such undertakings the possibility of eliminating competition in respect of a substantial part of the products in question.

The term "undertaking" essentially refers to businesses, but also any economic entity which carries on a trade.

Dominance and monopoly

Article 82 TEC is designed to prohibit abuse by very large corporations who dominate the market.

"Any abuse by one or more undertakings of a dominant position within the common market or in a substantial part of it shall be prohibited as incompatible with the common market insofar as it may affect trade between Member States.

This provision is then clarified through the use of some specific categories of behaviour which are deemed "abusive".

"Such abuse may, in particular, consist in (a) directly or indirectly imposing unfair purchase or selling prices or other unfair trading conditions; (b) limiting production, markets or technical development to the prejudice of consumers; (c) applying dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading parties, thereby placing them at a competitive disadvantage; (d) making the conclusion of contracts subject to acceptance by the other parties of supplementary obligations which, by their nature or according to commercial usage, have no connection with the subject of such contracts.

Mergers and acquisitions

Under the authority of Article 82 TEC, the European Commission became able not only to regulate the behaviour of large firms it claims abuse their dominant positions or market power, but also the possibility of firms gaining the position within the market structure that enables them to behave abusively in the first place. Regulation 139/2004 deals with mergers that have a "Community dimension" and lays out a procedure whereby all "concentrations" (i.e. mergers, acquisitions, takeovers) between undertakings are subject to approval by the European Commission.

Public sector regulation

Public sector industries, or industries which are by their nature providing a public service, are involved in competition law in many ways similar to private companies. Under EC law, Articles 86 and 87 create exceptions for the assured achievement of public sector service provision. Many industries, such as railways, telecommunications, electricity, gas, water and media have their own independent sector regulators. These government agencies are charged with ensuring that private providers carry out certain public service duties in line of social welfare goals.

Criminal law

In 2006, a toxic waste spill off the coast of Côte d'Ivoire, from a European ship, prompted the Commission to look into legislation against toxic waste. Environment Commissioner Stavros Dimas stated that "Such highly toxic waste should never have left the European Union". With countries such as Spain not even having a crime against shipping toxic waste Franco Frattini, the Justice, Freedom and Security Commissioner, proposed with Dimas to create criminal sentences for "ecological crimes". His right to do this was contested in 2005 at the Court of Justice resulting in a victory for the Commission. That ruling set a precedent that the Commission, on a supranational basis, may legislate in criminal law - something never done before to outlined in treaties. So far though, the only other use has been the intellectual property rights directive.[32] Motions were tabled in the European Parliament against that legislation on the basis that criminal law should not be an EU competence, but was rejected at vote.[33] However in October 2007 the Court of Justice ruled the Commission could not propose what the criminal sanctions could be, only that there must be some.[34]

See also

|

|

Notes

- ↑ According to the principle of Direct Effect first invoked in the Court of Justice's decision in Van Gend en Loos v. Nederlanse Administratie Der Belastingen, Eur-Lex .. See: Craig and de Búrca, ch. 5.

- ↑ According to the principle of Supremacy as established by the ECJ in Case 6/64, Falminio Costa v. ENEL [1964] ECR 585. See Craig and de Búrca, ch. 7. See also: Factortame Ltd. v. Secretary of State for Transport (No. 2) [1991] 1 AC 603, Solange II (Re Wuensche Handelsgesellschaft, BVerfG decision of 22 Oct. 1986 [1987] 3 CMLR 225,265) and Frontini v. Ministero delle Finanze [1974] 2 CMLR 372; Raoul George Nicolo [1990] 1 CMLR 173.

- ↑ See: Case 34/73, Variola v. Amministrazione delle Finanze [1973] ECR 981.

- ↑ "European Union consolidated treaty, (article 249, provisions for making regulations)" (PDF). European Commission. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/site/en/oj/2006/ce321/ce32120061229en00010331.pdf. Retrieved 8 November 2007.

- ↑ To do otherwise would require the drafting of legislation which would have to cope with the frequently divergent legal systems and administrative systems of all of the now 27 member states. See Craig and de Búrca, p. 115

- ↑ Art. 220 TEC

- ↑ Craig and de Burca (2007) p.72f

- ↑ see Art. 228 TEC

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Craig and de Burca (2007) p.73

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Article 223; Craig and de Burca (2007) p.67

- ↑ Article 222; Craig and de Burca (2007) p.67

- ↑ Craig and de Burca (2007) p.67

- ↑ "The Court of Justice of the European Communities". http://curia.europa.eu/en/instit/presentationfr/cje.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Craig and de Burca (2007) p.68

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "The Court of First Instance". http://curia.europa.eu/en/instit/presentationfr/tpi.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ↑ Craig and de Burca (2007) p.69

- ↑ Case 6/64, Falminio Costa v ENEL [1964] ECR 585, 593

- ↑ now found in Art. 86 and Art. 87

- ↑ "But this obligation does not give individuals the right to allege, within the framework of community law... either failure by the state concerned to fulfil any of its obligations or breach of duty on the part of the commission."

- ↑ Falminio Costa v ENEL [1964] ECR 585, 593 (C-6/64)

- ↑ in the U.K. see, Factortame Ltd v Secretary of State for Transport (No 2) [1991] 1 AC 603; in Germany see Solange II (Re Wuensche Handelsgesellschaft, BVerfG decision of 22 October 1986 [1987] 3 CMLR 225, 265); in Italy see Frontini v Ministero delle Finanze [1974] 2 CMLR 372; in France see, Raoul George Nicolo [1990] 1 CMLR 173

- ↑ see especially, Solange II (Re Wuensche Handelsgesellschaft, BVerfG decision of 22 October 1986 [1987] 3 CMLR 225,265)

- ↑ see Article 3 TEU for a list

- ↑ under Art 157 TFEU, C-43/75 Defrenne v Sabena [1976] ECR 455

- ↑ 85/374/EEC

- ↑ Case 228/69, Internationale Handelsgesellschaft mbH v. Einfuhr und Vorratsstelle für Getreide und Futtermittel [1970] ECR 1125; [1972] CMLR 255.

- ↑ Joint Declaration by the European Parliament, Council and the Commission concerning the protection of fundamental rights and the ECHR (OJ C 103, 27/04/1977 P. 1-2)

- ↑ By Article F of the Maastricht Treaty Maastricht Treaty.

- ↑ Craig, Paul; Grainne De Burca , P. P. Craig (2007). "Chapter 11 Human rights in the EU". EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-19-927389-8.

- ↑ Johnson, Ailish (2005). "Vol. 8 Memo Series (Page 6)". Social Policy: State of the European Union. http://www.princeton.edu/~smeunier/Johnson%20Memo.pdf. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- ↑ Commission v France (C-1/00) nb this case was brought under Art 226, for France's failure to fulfill its obligations under various EU directives, which are in turn sourced on the Articles 28 and 31

- ↑ Charter, David (2007). "A new legal environment". E!Sharp (People Power Process): pp. 23–5.

- ↑ Gargani, Giuseppe (2007). "Intellectual property rights: criminal sanctions to fight piracy and counterfeiting". European Parliament. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/expert/infopress_page/057-4356-078-03-12-909-20070319IPR04284-19-03-2007-2007-false/default_en.htm. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- ↑ Mahony, Honor (2007-10-23). "EU court delivers blow on environment sanctions". EU Observer. http://euobserver.com/9/25028. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

References

- Craig, Paul; Gráinne de Búrca (2007). EU Law, Text, Cases and Materials (4th ed. ed.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press . ISBN 978-0-19-927389-8.

- Steiner, Josephine; Lorna Woods; Christian Twigg-Flesner (2006). EU Law (9th ed. ed.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927959-3.

- Barnard, Catherine (2007). The Substantive Law of the EU: The Four Freedoms (2nd ed. ed.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929839-6.

- Tobler, Christa; Beglinger, Jacques (2010), Essential EU Law in Charts (2nd 'Lisbon' ed.), Budapest: HVG-ORAC, associated publication of E.M.Meijers Institute of Legal Studies, Leiden University. ISBN 978-963-258-086-9. With webcompanion: Eur-charts.eu Visualisation/graphic representations of EC law in the form of charts/diagrams.

External links

- EUR-Lex - online access to existing and proposed European Union legislation

- EUR-Lex: Treaties

- Summaries of EU legislation

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||