Eurozone

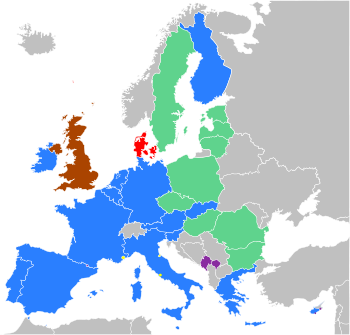

Eurozone as of 2010 Non-eurozone states using the euro Estonia; adopting in 2011[1] |

|

| Currency | euro |

|---|---|

| Union type | Economic & Monetary |

| Established | 1999 |

| Members | |

| Governance | |

| Political control | Euro Group |

| Group president | Jean-Claude Juncker |

| Issuing authority | European Central Bank |

| ECB president | Jean-Claude Trichet |

| Affiliated with | European Union |

| Statistics | |

| Population | 328,597,348 |

| GDP (PPP) | €8.4 trillion[2] |

| Interest rate | 1%[3][4] |

| Inflation | 0.3%[5] |

| Unemployment | 10%[6] |

| Trade balance | €22.3 bn surplus[7] |

The eurozone (pronunciation), officially the euro area,[8] is an economic and monetary union (EMU) of 16 European Union (EU) member states which have adopted the euro currency as their sole legal tender. It currently consists of Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain. Eight (not including Sweden, which has a de facto opt out) other states are obliged to join the zone once they fulfill the strict entry criteria.

Monetary policy of the zone is the responsibility of the European Central Bank, though there is no common representation, governance or fiscal policy for the currency union. Some cooperation does however take place through the euro group, which makes political decisions regarding the eurozone and the euro.

The eurozone can also be taken informally to include third countries that have adopted the euro, for example Montenegro (see details on these countries below). Three European microstates—Monaco, San Marino and the Vatican City—have concluded agreements with the European Union permitting them to use the euro as their official currency and mint coins,[9] but they are neither formally part of the eurozone[10][11] nor represented on the board of the European Central Bank.

Contents |

Members

In 1998 eleven European Union member-states had met the convergence criteria, and the eurozone came into existence with the official launch of the euro on 1 January 1999. Greece qualified in 2000 and was admitted on 1 January 2001. Physical coins and banknotes were introduced on 1 January 2002. Slovenia qualified in 2006 and was admitted on 1 January 2007. Cyprus and Malta qualified in 2007 and were admitted on 1 January 2008. Slovakia qualified in 2008 and joined on 1 January 2009. That makes 16 member states with 329 million people in the eurozone.

| State | Adopted | Population | Exceptions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 1 January 1999 | 8,356,707 | ||

| Belgium | 1 January 1999 | 10,741,048 | ||

| Cyprus | 1 January 2008 | 801,622 | ||

| Finland | 1 January 1999 | 5,325,115 | ||

| France | 1 January 1999 | 64,105,125 | ||

| Germany | 1 January 1999 | 82,062,249 | ||

| Greece | 1 January 2001 | 11,262,539 | ||

| Ireland | 1 January 1999 | 4,517,758 | ||

| Italy | 1 January 1999 | 60,090,430 | ||

| Luxembourg | 1 January 1999 | 491,702 | ||

| Malta | 1 January 2008 | 412,614 | ||

| Netherlands | 1 January 1999 | 16,481,139 | ||

| Portugal | 1 January 1999 | 10,631,800 | ||

| Slovakia | 1 January 2009 | 5,411,062 | ||

| Slovenia | 1 January 2007 | 2,053,393 | ||

| Spain | 1 January 1999 | 45,853,045 | ||

| Eurozone | 328,597,348 | |||

Enlargement

Eleven countries (i.e., Denmark, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania) are EU members but do not use the euro. Before joining the eurozone, a state must spend two years in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II). Since 1 January 2009, the National Central Banks (NCBs) of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Denmark have been participating in ERM II. The remaining currencies are expected to follow as soon as they meet the criteria. Few countries have declared a target date, and only Estonia has gained approval to join on 1 January 2011.[17]

Denmark and the United Kingdom obtained special opt-outs in the original Maastricht Treaty. Both countries are legally exempt from joining the eurozone unless their governments decide otherwise, either by parliamentary vote or referendum. The current Danish government has announced plans to hold a referendum on the issue following the adoption of the Treaty of Lisbon.[18][19][20] Sweden gained a de facto opt-out by using a legal loophole. It is required to join the eurozone as soon as it fulfills the convergence criteria, which includes being part of ERM II for two years, while joining ERM II is voluntary.[21][22] Sweden has so far decided not to join ERM II.

The 2008 financial crisis increased interest in Denmark and initially in Poland to join the eurozone, and in Iceland to join the European Union, a pre-condition for adopting the euro.[23] Since Latvia requested help from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), as a precondition, it may be forced to drop its currency peg. This would take Latvia out of ERM II and possibly move the euro adoption date even further from 2013 than currently planned.[24] However, by 2010, the debt crisis in the euro zone caused interest from Poland and the Czech Republic to cool.[25]

Non-member usage

The euro is also used in countries outside the EU. Three states (i.e., Monaco, San Marino, and Vatican City)[26][27] have signed formal agreements with the EU to use the euro and mint their own coins. Nevertheless, they are not considered part of the eurozone by the ECB and do not have a seat in the ECB or Euro Group.

Some countries (i.e., Andorra, Kosovo,[a] and Montenegro) have officially adopted the euro as their sole currency without an agreement and, therefore, have no issuing rights. Andorra is currently negotiating an agreement with the EU. These states are not considered part of the eurozone by the ECB. However, in some usage, the term eurozone is applied to all territories that have adopted the euro as their sole currency.[28][29][30] Further unilateral adoption of the euro (euroisation), by both non-euro EU and non-EU members, is opposed by the ECB and EU.[31]

Administration and representation

.jpg)

The monetary policy of all countries in the eurozone is managed by the European Central Bank (ECB) and the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) which comprises the ECB and the central banks of the EU states who have joined the zone. Countries outside the European Union, even those with monetary agreements such as Monaco, are not represented in these institutions. The ECB is entitled to authorise the design and printing of euro banknotes and the minting of euro coins, and its president is currently Jean-Claude Trichet.

The eurozone is represented politically by its finance ministers, known collectively as the Euro Group, and is presided over by a president, currently Jean-Claude Juncker. The finance ministers of the EU member states that use the euro meet a day before a meeting of the Economic and Financial Affairs Council (Ecofin) of the Council of the European Union. The Group is not an official Council formation but when the full EcoFin council votes on matters only affecting the eurozone, only Euro Group members are permitted to vote on it.[32][33][34]

On 15 April 2008 in Brussels, Juncker suggested that the eurozone should be represented at the International Monetary Fund as a bloc, rather than each member state separately: "It is absurd for those 15 countries not to agree to have a single representation at the IMF. It makes us look absolutely ridiculous. We are regarded as buffoons on the international scene."[35] However Finance Commissioner Joaquín Almunia stated that before there is common representation, a common political agenda should be agreed.[35]

Economy

Comparison table

| Population | GDP | % world | Exports | Imports | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eurozone | 317 million | €8.4 trillion | 14.6% | 21.7% GDP | 20.9% GDP |

| EU (27) | 494 million | €11.9 trillion | 21.0% | 14.3% GDP | 15.0% GDP |

| United States | 300 million | €11.2 trillion | 19.7% | 10.8% GDP | 16.6% GDP |

| Japan | 128 million | €3.5 trillion | 6.3% | 16.8% GDP | 15.3% GDP |

| GDP in PPP, exports/imports as goods and services excluding intra-EU trade. | |||||

Inflation

HICP figures from the ECB:[36]

|

|

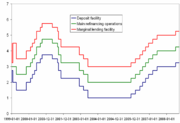

Interest rates

Interest rates for the eurozone, set by the ECB since 1999. Levels are in percentages per annum. Prior to June 2000, the main refinancing operations were fixed rate tenders. This was replaced by variable rate tenders, the figures indicated in the table after that refer to the minimum interest rate at which counterparties may place their bids.[4]

| Date | Deposit facility | Main refinancing operations | Marginal lending facility |

|---|---|---|---|

| 01 Jan 1999 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 4.50 |

| 04 Jan 1999[37] | 2.75 | 3.00 | 3.25 |

| 22 Jan 1999 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 4.50 |

| 09 Apr 1999 | 1.50 | 2.50 | 3.50 |

| 05 Nov 1999 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 |

| 04 Feb 2000 | 2.25 | 3.25 | 4.25 |

| 17 Mar 2000 | 2.50 | 3.50 | 4.50 |

| 28 Apr 2000 | 2.75 | 3.75 | 4.75 |

| 09 Jun 2000 | 3.25 | 4.25 | 5.25 |

| 28 Jun 2000 | 3.25 | 4.25 | 5.25 |

| 01 Sep 2000 | 3.50 | 4.50 | 5.50 |

| 06 Oct 2000 | 3.75 | 4.75 | 5.75 |

| 11 May 2001 | 3.50 | 4.50 | 5.50 |

| 31 Aug 2001 | 3.25 | 4.25 | 5.25 |

| 18 Sep 2001 | 2.75 | 3.75 | 4.75 |

| 09 Nov 2001 | 2.25 | 3.25 | 4.25 |

| 06 Dec 2002 | 1.75 | 2.75 | 3.75 |

| 07 Mar 2003 | 1.50 | 2.50 | 3.50 |

| 06 Jun 2003 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 |

| 06 Dec 2005 | 1.25 | 2.25 | 3.25 |

| 08 Mar 2006 | 1.50 | 2.50 | 3.50 |

| 15 Jun 2006 | 1.75 | 2.75 | 3.75 |

| 09 Aug 2006 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 |

| 11 Oct 2006 | 2.25 | 3.25 | 4.25 |

| 13 Dec 2006 | 2.50 | 3.50 | 4.50 |

| 14 Mar 2007 | 2.75 | 3.75 | 4.75 |

| 13 Jun 2007 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 5.00 |

| 09 Jul 2008 | 3.25 | 4.25 | 5.25 |

| 08 Oct 2008 | 2.75 | 4.75 | |

| 09 Oct 2008 | 3.25 | 4.25 | |

| 15 Oct 2008 | 3.25 | 3.75 | 4.25 |

| 12 Nov 2008 | 2.75 | 3.25 | 3.75 |

| 10 Dec 2008 | 2.00 | 2.50 | 3.00 |

| 21 Jan 2009 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 |

| 11 Mar 2009 | 0.50 | 1.50 | 2.50 |

| 08 Apr 2009 | 0.25 | 1.25 | 2.25 |

| 13 May 2009 | 0.25 | 1.00 | 1.75 |

Public debt

The following table states the ratio of public debt to GDP in percent for EU and other selected European states. Eurozone and non-euro EU members are marked as Euro and EU respectively.

| Country | CIA 2008[38] | OECD 2008[39] | IMF 2008[40] | CIA 2009[41] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euro | 103.70 | 114.4 | 104.3 | 115.20 | |

| Euro | 90.10 | 102.6 | 108.10 | ||

| Euro | 80.80 | 93.5 | 99.00 | ||

| 23.00 | 96.3 | 95.10 | |||

| Euro | 67.00 | 75.7 | 65.2 | 79.70 | |

| EU | 73.80 | 77.0 | 78.00 | ||

| Euro | 62.60 | 68.8 | 76.4 | 77.20 | |

| Euro | 64.20 | 75.2 | 75.20 | ||

| EU | 47.20 | 56.8 | 43.4 | 68.50 | |

| Euro | 67.00 | ||||

| Euro | 58.80 | 66.2 | 66.50 | ||

| Euro | 31.50 | 48.5 | 63.70 | ||

| Euro | 43.00 | 65.8 | 62.20 | ||

| 48.90 | 61.00 | ||||

| 51.20 | 54.90 | ||||

| Euro | 49.00 | 52.40 | |||

| Euro | 37.50 | 44.2 | 50.00 | ||

| 37.10 | 48.50 | ||||

| EU | 41.60 | 54.0 | 47.50 | ||

| Euro | 33.00 | 40.7 | 46.60 | ||

| EU | 36.50 | 47.0 | 43.20 | ||

| EU | 21.80 | 39.8 | 38.10 | ||

| 38.00[42] | 38.00[42] | ||||

| Euro | 35.00 | 30.8 | 34.60 | ||

| EU | 29.40 | 40.7 | 32.80 | ||

| EU | 17.00 | 32.50 | |||

| Euro | 22.00 | 31.40 | |||

| EU | 11.90 | 31.30 | |||

| 37.00[43] | 31.30 | ||||

| 35.90 | 24.50 | ||||

| EU | 14.10 | 20.00 | |||

| EU | 16.70 | 14.70 | |||

| Euro | 7.20 | 16.3 | 14.50 | ||

| EU | 3.80 | 7.50 |

Fiscal policies

The primary means for fiscal coordination within the EU lies in the Broad Economic Policy Guidelines which are written for every member state, but with particular reference to the 16 current members of the eurozone. These guidelines are not binding, but are intended to represent policy coordination among the EU member states, so as to take into account the linked structures of their economies.

For their mutual assurance and stability of the currency, members of the eurozone have to respect the Stability and Growth Pact, which sets agreed limits on deficits and national debt, with associated sanctions for deviation. The Pact originally set a limit of 3% of GDP for the yearly deficit of all eurozone member states; with fines for any state which exceeded this amount. In 2005, Portugal, Germany, and France had all exceeded this amount, but the Council of Ministers had not voted to fine those states. Subsequently, reforms were adopted to provide more flexibility and ensure that the deficit criteria took into account the economic conditions of the member states, and additional factors.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development downgraded its economic forecasts on 20 March 2008 for the eurozone for the first half of 2008. Europe does not have room to ease fiscal or monetary policy, the 30-nation group warned. For the euro zone, the OECD now forecasts first-quarter GDP growth of just 0.5%, with no improvement in the second quarter, which is expected to show just a 0.4% gain.

Late 2000s recession and reform

As a result of the global financial crisis that began in 2007/2008, the eurozone entered its first official recession in the third quarter of 2008, official figures confirmed in January 2009.[44] On 11 October 2008 the Euro Group heads of state and government (rather than finance ministers) held an extraordinary summit in Paris to define a joint action plan for the eurozone and the European Central Bank to stabilise the European economy.

The leaders hammered out a plan to confront the financial crisis which will involve hundreds of billions of euros of new initiatives to head off a feared "meltdown". They agreed a bank rescue plan: governments would buy into banks to boost their finances and guarantee interbank lending. Coordination against the crisis is considered vital to prevent the actions of one country harming another and exacerbating the bank solvency and credit shortage problems. In the Great Depression, so-called "beggar-thy-neighbour" measures taken unilaterally by countries are considered to have deepened the economic loss.[45]

Despite initial fears by speculators in early 2009 that the stress of such a large recession could lead to the break up of the eurozone, the euro's position actually strengthened as the year progressed. Far from the poorer performing economies moving further away and becoming a default risk, bond yield spreads between Germany and the weakest economies decreased easing the strain on these economies. The ECB has been attributed much of the credit for the turn around in fortunes, injecting €500bn into the banks in June.[46]

In early 2010, fears of a sovereign debt crisis developed concerning eurozone countries such as Greece, Spain, Ireland, Portugal and Italy.[47] This led to a crisis of confidence as well as the widening of bond yield spreads and risk insurance on credit default swaps between these countries and other eurozone members, specifically Germany and France..

With Greece facing severe economic difficulties, the EU adopted a plan to help its recovery, including surveillance from the ECB and loans. The European Council also stated for the first time that if it came to it, the EU would bail out the country if needed.[48] The crisis has sparked renewed discussion of fiscal integration as the lack of a federal treasury and budget being seen as a major weakness of the eurozone[49] and there is the possibility the upcoming 10-year economic plan may lay the foundations for fiscal co-ordination.[50] The attack by speculators on Greece was seen by some, including the Greek government, as an attack on the eurozone, using Greece as the weak-link.[51][52] A 30 billion euro bailout for Greece was triggered in April 2010.[53]

Agreements and proposals

The economic crisis prompted calls for a more integrated eurozone,[54] from bailing out member states to fiscal union.

Bailout mechanism

On 25 March 2010, the European Council agreed on a bailout mechanism for Greece and, with the approval of the European Council, for any other country in need of it. The majority of the €22 billion loan funds came from bilateral contributions from eurozone members, with substantial extra contributions from the IMF. Germany backed IMF involvement and a compromise with France saw the IMF's input limited. There was concern that a eurozone bailout would violate the EU treaties and German law, although the plan stresses that all actions will be carried out in accordance with those rules. The plan also provides for a greater role for the European Council and that "the European Council should become the economic government of the European Union and we [the European Council] propose to increase its role in economic surveillance." German finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble recently called for eurozone rules to be significantly tightened, including the possibility of expelling members that repeatedly flaunt restrictions.[55]

In April 2010, the bailout mechanism was triggered, with €30 billion being loaned to Greece.[53] In May, the EU established a full fund of €750 billion to stabilise the eurozone as a whole: 440 billion from eurozone states, 60 billion from emergency European Commission funds, and 250 billion from the IMF.[56] A special purpose vehicle (SPV) called "European Financial Stability Facility" (EFSF) with base in Luxembourg was created. The ESFS will issue debt on capital markets, backed by guarantees from the eurozone states. Money raised will be lent to indebted eurozone governments after a restructuring programme is agreed.[57]

In June 2010 there were reports that the EU was preparing to release funds to Spain. This was denied but German Chancellor Angela Merkel confirmed Spain could access the funds if necessary.[58]

Peer review and sanctions

In June 2010 broad agreement was reached on a controversial proposal for member states to peer review each others' budgets prior to their presentation to national parliaments. Although showing the entire budget to each other was opposed by Germany, Sweden and the UK, each government would present to their peers and the Commission their estimates for growth, inflation, revenue and expenditure levels six months before they go to national parliaments. If a country was to run a deficit, they would have to justify it to the rest of the EU while countries with a debt more than 60% of GDP would face greater scrutiny.[57]

The plans would apply to all EU members, not just the eurozone, and have to be approved by EU leaders along with proposals for states to face sanctions before they reach the 3% limit in the Stability and Growth Pact. Poland has criticised the idea of withholding regional funding for those who break the deficit limits, as that would only impact the poorer states.[57] In June 2010 France agreed to back Germany's plan for suspending the voting rights of members who breach the rules.[58]

Monetary fund

There have been a number of proposals for greater fiscal union. This has come in the forms of a finance ministry or International Monetary Fund style body. Belgian Prime Minister Yves Leterme proposed a European Debt Agency which would manage eurozone government debt.[59] A similar plan came from Wolfgang Schäuble, Germany's Minister of Finance, who proposed creating a European version of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) so IMF style resources and expertise could be used, while solving the problem within Europe. The plan is also backed by France, the Socialists and the Italian President who stated that "The European Central Bank [and] the European institutions are aware that there's something missing from our common tool box to tackle unforeseen and serious crises in one of the eurozone nations." The Commission is preparing a formal proposal on an EMF[60] however some see the plan as too far fetched as there is no appetite for treaty reform after Lisbon.[59]

Regardless, an EMF or EDA wouldn't be operational in time to help Greece. French President Sarkozy declared that "France is by the side of Greece in the most resolute fashion ... The euro is our currency. It implies solidarity. There can be no doubt on the expression of this solidarity" and that if the eurozone let a member fail, there would have been no point in creating the currency.[60] In the long term, Germany wants an EMF to be accompanied by stronger enforcement mechanisms: for example a country that does not reign in its debt can have its EU funds withdrawn or its voting rights suspended. However, such German-inspired plans have been described as unacceptable infringements on the sovereignty of eurozone member states [61] and are opposed by key EU member states such as France and Italy.[62]

The proposals may result in the biggest overhaul of the eurozone since the euro's launch. With the guarantee that a member state would be bailed out, the market based system where a state must keep its own finances in check is being replaced by a state-run system with the EU bailing out countries in return for oversight over their finances. This is seen as vital as a Greek collapse would bring the rest of the EU with it; although Germany would be a big financial contributor, its industry relies on exports and its banks have investments in Greece. It requires giving up another chunk of sovereignty, funds or financial independence and would give the eurozone a stronger base of a fiscal-political union that has been another weak point in its design.[63]

Other proposals

Spain has proposed that the EU enact the article in the Lisbon Treaty which will create the European Public Prosecutor. Spain for its part wants this new EU organ to co-ordinate legal action against those speculators who were attacking the euro.[64] Finally, French President Nicolas Sarkozy called the Eurogroup to be replaced by a "clearly identified economic government" for the eurozone, stating it was not possible for the eurozone to continue without it. The eurozone economic government would discuss issues with the European Central Bank, which would remain independent.[65] This government would come in the form of a regular meeting of the eurozone heads of state and government (similar to the European Council) rather than simply the finance ministers which happens with the current Eurogroup. Sarkozy stated that "only heads of state and government have the necessary democratic legitimacy" for the role. This idea was based on the meeting of eurozone leaders in 2008 who met to agree a co-ordinated eurozone response to the banking crisis.[66]

This is in contrast to an early proposal from former Belgian Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt who saw the European Commission taking a leading role in a new economic government, something that would be opposed by the less integrationist states.[33] Sarkozy's proposal was opposed by Eurogroup chair Jean-Claude Juncker who does not think Europe is ripe for such a large step[33] and opposition from Germany killed off the proposal.[66][58] Merkel approved of the idea of an economic government, but for the whole of the EU, not just the eurozone as doing so could split the EU and relegate non-euro states to second class members.[58]

See also

- Economy of the European Union

- European Central Bank

- Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union

- Special member state territories and the European Union

Notes and references

| a. | ^ Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Serbia and the self-proclaimed Republic of Kosovo. Kosovo declared independence on 17 February 2008, while Serbia claims it as part of its own sovereign territory. Kosovo is recognised by 72 of the 192 UN member states. |

- ↑ http://www.france24.com/en/20100608-eu-ministers-offer-estonia-entry-eurozone-january-1-currency-europe

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 The euro: An international currency, Europa (web portal)

- ↑ WORLD INTEREST RATES TABLE, FX street

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Key ECB interest rates, ECB

- ↑ HICP - all items - annual average inflation rate Eurostat

- ↑ Harmonised unemployment rate by gender - total - [teilm020]; Total % (SA) Eurostat

- ↑ For the whole of 2009. Euroindicators 17 February 2010, Eurostat

- ↑ "Countries, languages, currencies". Interinstitutional style guide. the EU Publications Office. http://publications.europa.eu/code/en/en-370300.htm. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

The euro area, European Central Bank - ↑ "Agreements on monetary relations (Monaco, San Marino, the Vatican and Andorra)". http://europa.eu/legislation_summaries/economic_and_monetary_affairs/institutional_and_economic_framework/l25040_en.htm. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ↑ A glossary issued by the ECB defines “euro area”, without mention of Monaco, San Marino, or the Vatican.

- ↑ The agreements contain provisions that do not apply to the eurozone proper. For example, banks in Monaco need the consent of the ECB to gain access to national payment systems in France.

- ↑ The self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus is not recognised by the EU and uses the Turkish lira. However the euro does circulate widely.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 French Pacific territories use the CFP franc.

- ↑ Uses Swiss franc. However the euro is also accepted and circulate widely.

- ↑ Aruba uses the Aruban florin. It is part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, but not EU.

- ↑ The Netherlands Antilles uses the Antillean guilder. It is part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, but not the EU. The guilder typically followed the US dollar, but the Netherlands Antilles is to be dissolved with some islands becoming part of the EU. The future currency situation is unclear.

- ↑ Ministers offer Estonia entry to eurozone January 1

- ↑ "Newsvine - Denmark to Hold New Referendum on Euro". Newsvine.com. http://www.newsvine.com/_news/2007/11/22/1115165-denmark-to-hold-new-referendum-on-euro. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ↑ Denmark to hold new referendum on euroBy Robert Anderson in Stockholm (November 22, 2007). "FT.com / World - Denmark to hold new referendum on euro". Ft.com. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/79799902-9909-11dc-bb45-0000779fd2ac.html. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ↑ "Denmark to hold second euro referendum - EurActiv.com | EU - European Information on Economy & Euro". Euractiv.com. 2007-11-23. http://www.euractiv.com/en/euro/denmark-hold-second-euro-referendum/article-168631. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ↑ "Swedish Parliament EU Information". Swedish Parliament. 2009-12-04. http://www.eu-upplysningen.se/Amnesomraden/EMU/Sverige-och-EMU/. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ↑ "Information on ERM II". European Commission. 2009-12-22. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/euro/adoption/erm2/index_en.htm. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ↑ Dougherty, Carter (2008-12-01). "Buffeted by financial crisis, countries seek euro's shelter". International Herald Tribune (The New York Times). http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/12/01/business/euro.php?page=1. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ↑ "€5bn question is whether IMF will force Latvia to give up currency peg". Business News Europe. http://businessneweurope.eu/storyf1384. Retrieved 2008-12-03.

- ↑ "Czechs, Poles cooler to euro as they watch debt crisis". Reuters. June 16, 2010. http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSLDE65F15Z20100616. Retrieved June 18, 2010.

- ↑ "Agreements on monetary relations (Monaco, San Marino, the Vatican and Andorra)". European Communities. 2004-09-30. http://europa.eu/scadplus/leg/en/lvb/l25040.htm. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ↑ The euro outside the euro area, Europa (web portal)

- ↑ "European Foundation Intelligence Digest". Europeanfoundation.org. http://www.europeanfoundation.org/docs/117id.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ "Europe | The eurozone's 13th member". BBC News. 2001-12-11. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/1696122.stm. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ "Ecb: "Unilateral Euroization By Iceland Comes With Real Costs And Serious Risks"". Lawofemu.info. 2008-02-15. http://www.lawofemu.info/blog/2008/02/ecb-unilateral.html. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ Treaty of Lisbon (Provisions specific to member states whose currency is the euro), EurLex

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 An economic government for the eurozone? PDF, Federal Union

- ↑ PROTOCOLS, Official Journal of the European Union

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Vucheva, Elitsa (2008-04-15)eurozone countries should speak with one voice, Juncker says, EU Observer.

- ↑ European Central Bank (2007-12-14). "Euro area (changing composition) - HICP - Overall index, Annual rate of change, Eurostat, Neither seasonally or working day adjusted". http://sdw.ecb.europa.eu/quickview.do?SERIES_KEY=122.ICP.M.U2.N.000000.4.ANR. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- ↑ The ECB announced on 22 December 1998 that, between 4 and 21 January 1999, there would be a narrow corridor of 50 base points interest rates for the marginal lending facility and the deposit facility in order to help the transition to the ECB's interest regime.

- ↑ "The World Factbook - (Rank Order - Public debt)". Archived from the original on 2008-10-15. http://www.webcitation.org/query?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cia.gov%2Flibrary%2Fpublications%2Fthe-world-factbook%2Frankorder%2F2186rank.html&date=2008-10-15. Retrieved 2008-10-15. (all estimates 2008 data unless noted)

- ↑ ""Annex Table 32. General government gross financial liabilities" in OECD Economic Outlook". OECD. 2009-12-11. http://www.oecd.org/document/61/0,3343,en_2649_34573_2483901_1_1_1_1,00.html. Retrieved 2009-12-11. (2008 estimates; direct URL of datasheet is http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/5/51/2483816.xls)

- ↑ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". IMF. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2008/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?sy=2004&ey=2009&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=0&pr1.x=59&pr1.y=16&c=193%2C542%2C122%2C137%2C124%2C181%2C156%2C138%2C423%2C196%2C128%2C142%2C172%2C182%2C132%2C576%2C134%2C961%2C174%2C184%2C532%2C144%2C176%2C146%2C178%2C528%2C436%2C112%2C136%2C111%2C158&s=GGD_NGDP&grp=0&a=. Retrieved 2008-12-11. (General government gross debt 2008 estimates rounded to one decimal place)

- ↑ "The World Factbook - (Rank Order - Public debt)". Archived from the original on 2010-03-02. http://www.webcitation.org/5nvfxCBRI. Retrieved 2010-03-02.(all estimates 2009 data unless noted)

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 2006 Data

- ↑ 2007 Data

- ↑ EU data confirms eurozone's first recession, EUbusiness.com, January 8, 2009

- ↑ "European leaders agree crisis rescue at summit — EUbusiness.com - business, legal and economic news and information from the European Union". Eubusiness.com. http://www.eubusiness.com/news-eu/1223856121.86. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ↑ Oakley, David and Ralph Atkins (17 September 2009) Eurozone shows its strength in a crisis, Financial Times

- ↑ Brian Blackstone, Tom Lauricella, and Neil Shah (5 February 2010). "Global Markets Shudder: Doubts About U.S. Economy and a Debt Crunch in Europe Jolt Hopes for a Recovery". The Wall Street Journal. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB20001424052748704041504575045743430262982.html. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ↑ Willis, Andrew (12 February 2010) Van Rompuy: Eurozone will bail out Greece if needed, EU Observer

- ↑ Irvin, George (11 February 2010) Comment: How serious is the euro debt crisis?, EU observer

- ↑ Willis, Andrew (18 February 2010) Greek drama heightens debate on economic co-ordination, EU Observer

- ↑ Greece rejects bailout as eurozone worries grow, Euractiv

- ↑ Sarkozy to 'speculators': Lay off Greece, Associated Press

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Wray, Richard (11 April 2010) EU ministers agree Greek bailout terms The Guardian

- ↑ First step towards more integrated eurozone, Financial Times

- ↑ Willis, Andrew (25 March 2010) Eurozone leaders agree on Franco-German bail-out mechanism, EU Observer

- ↑ EU and IMF agree 750 billion-euro fund for crisis-hit eurozone members, France 24 - Reuters 10 May 2010

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 EU agrees controversial peer review of national budgets, EU Observer

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 58.3 Willis, Andrew (15 June 2010) Merkel: Spain can access aid if needed, EU Observer

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Belgian PM Leterme proposes European Debt Agency, The Guardian

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Plans emerge for 'European Monetary Fund' EU Observer

- ↑ (English) see M. Nicolas Firzli, 'Greece and the EU Debt Crisis', http://www.canadianeuropean.com/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/Greece__the_EU_Debt_Crisis_VN__Al-Nahar_Feb-March_2010.7383827.pdf, retrieved 2010-03-15

- ↑ Eurozone eyes IMF-style fund, Financial Times

- ↑ Eurozone overhaul Die Zeit on Presseurop, 12 February 2010

- ↑ Spain calls for EU prosecutor to protect euro, Reuters

- ↑ "Sarkozy pushes eurozone 'economic government', France 24 (21 October 2008)

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Germany rejects idea of eurozone 'economic government': report, EU Business (21 October 2008)

External links

- European Central Bank

- European Commission - Economic and Financial Affairs - Eurozone

- Eurozone in crisis dossier by Radio France Internationale in English June 2010

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||