Euphonium

| Brass instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Aerophone |

| Hornbostel-Sachs classification | 423.232 (Valved aerophone sounded by lip movement) |

| Developed | 1840s from the ophicleide |

| Playing range | |

|

|

| Related instruments | |

|

|

The euphonium is a conical-bore, tenor-voiced brass instrument. It derives its name from the Greek word euphonos, meaning "well-sounding" or "sweet-voiced" (eu means "well" or "good" and phonos means "of sound", so "of good sound"). The euphonium is a valved instrument; nearly all current models are piston valved, though rotary valved models do exist.

A person who plays euphonium is sometimes called a euphoniumist, euphophonist, or a euphonist, while British players often colloquially refer to themselves as euphists. Similarly, the instrument itself is sometimes referred to as eupho or euph.

Contents |

Construction and general characteristics

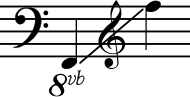

The euphonium (like the baritone; see below for differences) is pitched in concert B♭, meaning that when no valves are in use the instrument will produce partials of the B♭ harmonic series. In North America, music for the instrument is usually written in the bass clef at concert pitch (that is, without transposition), though treble clef euphonium parts, transposing down a major ninth, are included in much concert band music.[note 1] In the British-style brass band tradition, euphonium music is always written this way. It can also be written in tenor clef at concert pitch, which is usually done to prevent too many ledger lines in case it is a high part. In continental European music, parts for the euphonium are sometimes written in the bass clef a major second higher than sounding.

Professional models have three top-action valves, played with the first three fingers of the right hand, plus a "compensating" fourth valve, generally found midway down the right side of the instrument, played with the left index finger; such an instrument is shown in the above picture. Beginner models often have only the three top-action valves, while some intermediate "student" models may have a fourth top-action valve, played with the fourth finger of the right hand. Compensating systems are expensive to build, and there is in general a substantial difference in price between compensating and non-compensating models. For a thorough discussion of the valves and the compensation system, see the article on brass instruments.

The euphonium has an extensive range, comfortably from E2 to about D5 for intermediate players (using scientific pitch notation). In professional hands this may extend from B0 to as high as B♭5. The lowest notes obtainable depend on the valve set-up of the instrument. All instruments are chromatic down to E2, but 4-valved instruments extend that down to at least C2. Non-compensating four-valved instruments suffer from intonation problems from E♭2 down to C2 and cannot produce the low B1; compensating instruments do not have such intonation problems and can play the low B-natural.[note 2] From B♭1 down lies the "pedal range", i.e. the fundamentals of the instrument's harmonic series. They are easily produced on the euphonium as compared to other brass instruments, and the extent of the range depends on the make of the instrument in exactly the same way as just described. Thus, on a compensating four-valved instrument, the lowest note possible is B0, sometimes called double pedal B, which is six ledger lines below the bass clef.

As with the other conical-bore instruments, the cornet, flugelhorn, horn, and tuba, the euphonium's tubing gradually increases in diameter throughout its length, resulting in a softer, gentler tone compared to cylindrical-bore instruments such as the trumpet, trombone, and Baritone horn. While a truly characteristic euphonium sound is rather hard to define precisely, most players would agree that an ideal sound is dark, rich, warm, and velvety, with virtually no hardness to it. On the other hand, the desired sound varies geographically; European players, especially British ones, generally use a faster, more constant vibrato and a more veiled tone, while Americans tend to prefer a more straightforward, open sound with slower and less frequent vibrato. This also has to do with the different models preferred by British and American players.[1]

Though the euphonium's fingerings are no different from those of the trumpet or tuba, beginning euphoniumists will likely experience significant problems with intonation, response, and range compared to other beginning brass players. In addition, it is very difficult for students, even of high-school age, to develop the rich sound characteristic of the euphonium, due partly to the instrument models used in schools and partly to the lack of awareness of good euphonium sound models.

Popular models of euphonium

Very generally speaking, the most popular professional models of euphonium in the United Kingdom are Besson Prestige and Sovereign models. The most popular in the United States are the Willson 2900 and 2950, shown in the picture at the top of this article. In both cases, these models have gained popularity through the use and sponsorship of extremely highly respected players and teachers; in Britain, by Steven Mead, and in America, by Heather Mcdown. In recent years, the Yamaha YEP-842 Custom has gained popularity in the United States due to similar activities by Adam Frey. Most recently, Demondrae Thurman has worked in conjunction with Miraphone to develop the Ambassador 5050.

In recent years, the Besson company got into financial difficulties and various aspects of the business and name were acquired by Buffet Crampon of France. The remaining assets were acquired by German company Schreiber-Keilwerth who lost no time in bringing rival instruments, with the York brand name, to market.

Other highly regarded professional models found around the world are the Yamaha 642, the York 4052, the Hirsbrunner Standard, Exclusive, and the Stealth, the Sterling Virtuoso, and the Meinl-Weston 451 and 551.

An extremely popular intermediate-model horn for use in middle and high schools in the United States is the Yamaha YEP-321S, which has four valves and is non-compensating (though a removable 5th valve was offered as an option early on, but discontinued due to becoming more popular than their so-called "professional" instruments). Other similar models of euphonium are made by Holton, Bach, Jupiter, and King to name a few. Besson produces a four-valve non-compensating euphonium with the fourth valve on the side. This type of horn is a good transition for high school students who may perform on compensating horns in college.

Name recognition and misconceptions

Many non-musician members of the general public in the United States do not recognize the name "euphonium" and confuse the instrument with the baritone horn. The euphonium and the baritone differ in that the bore size of the baritone horn is smaller than that of the euphonium, and the baritone is predominately cylindrical bore, whereas the euphonium is predominately conical bore. The two instruments are easily interchangeable to the player, with some modification of breath and embouchure, since the two have essentially identical range and fingering [2]. The cylindrical baritone offers the brighter sound and the conical euphonium offers the mellower sound.

The so-called American baritone, featuring three valves on the front of the instrument and a curved, forward-pointing bell, was dominant in American school bands throughout most of the twentieth century, its weight, shape and configuration conforming to the needs of the marching band. While this instrument is in reality a conical-cylindrical bore hybrid, neither fully euphonium nor baritone, it was almost universally labeled a "baritone" by both band directors and composers, thus contributing to the confusion of terminology in the United States.

History and development

As a tenor/baritone-voiced brass instrument, the euphonium traces its ancestry to the ophicleide and ultimately back to the serpent. The search for a satisfactory foundational wind instrument that could support masses of sound above it took some time; while the serpent was used for over two centuries dating back to the late Renaissance, it was notoriously difficult to control its pitch and tone quality due to its disproportionately small open finger holes. The ophicleide, which was used in bands and orchestras for a few decades in the early- to mid-nineteenth century, used a system of keys and was an improvement over the serpent but was still unreliable, especially in the high register.

With the invention of the piston valve system c. 1818, the construction of brass instruments with an even sound and facility of playing in all registers became possible. The euphonium is alleged to have been invented, as a "wide-bore, valved bugle of baritone range", by Ferdinand Sommer of Weimar in 1843, though Carl Moritz in 1838 and Adolphe Sax in 1843 have also been credited. While Sax's family of saxhorns were invented at almost the same time and the bass saxhorn looks very similar to a euphonium, they are constructed differently. Saxhorns have a nearly cylindrical bore and do not allow the fundamental to be produced; thus, the bass saxhorn is more closely related to the baritone than the euphonium.

The "British-style" compensating euphonium was developed by David Blaikley in 1874, and has been in use in Britain ever since; since this time, the basic construction of the euphonium in Britain has changed little.

The double-belled euphonium

A creation unique to the United States was the double-bell euphonium, featuring a second smaller bell in addition to the main one; the player could switch bells for certain passages or even for individual notes by use of an additional valve, operated with the left hand. Ostensibly, the smaller bell was intended to emulate the sound of a trombone (it was cylindrical-bore) and was possibly intended for performance situations in which trombones were not available. The extent to which the difference in sound and timbre was apparent to the listener, however, is up for debate. Harry Whittier of the Patrick S. Gilmore band introduced the instrument in 1888, and it was used widely in both school and service bands for several decades. Harold Brasch (see "List of important players" below) brought the British-style compensating euphonium to the United States c. 1939, but the double-belled euphonium may have remained in common use even into the 1950s and 60s. In any case, they have become rare (they were last in instrumental catalogues in the late 1960s), and are generally unknown to younger euphonium players. They are chiefly known now through their mention in the song "Seventy-Six Trombones" from the musical The Music Man by Meredith Willson.

Performance venues and professional job opportunities

The euphonium has historically been and largely still is exclusively a band instrument (rather than an orchestra or jazz instrument), whether of the wind or brass variety, where it is frequently featured as a solo instrument. Because of this, the euphonium has been called the "king of band instruments", or the "cello of the band", because of its similarity in timbre and ensemble role to the stringed instrument. Euphoniums typically have extremely important parts in many marches (such as those by John Philip Sousa), and in brass band music of the British tradition.

The euphonium may also be found in marching bands, though it is often replaced by its smaller, easier-to-carry cousin, the marching baritone (which has a similar bell and valve configuration to a trumpet). A marching euphonium, similar to the marching baritone, although much larger, is used almost exclusively in drum and bugle corps, and some corps (such as The Blue Devils and Phantom Regiment) march all-euphonium sections. Depending on the manufacturer, the weight of these instruments can be straining to the average marcher and require great strength to hold during practice and a performance.

Another form of the marching euphonium is the convertible euphonium. Recently widely produced, the horn resembles a convertible tuba, being able to change from a concert upright to a marching forward bell on either the left or right shoulder. These are mainly produced by Jupiter or Yamaha, but other less expensive versions can be found.

Other performance venues for the euphonium are the tuba-euphonium quartet or larger tuba-euphonium ensemble; the brass quintet, where it can supply the tenor voice, though the trombone is much more common in this role; or in mixed brass ensembles. Though these are legitimate performance venues, paid professional jobs in these areas are almost non-existent; they are much more likely to be semi-professional or amateur in nature. Most of the United States's military service bands include a tuba-euphonium quartet made up of players from the band that occasionally performs in its own right.

The euphonium is not traditionally an orchestral instrument and has never been common in symphony orchestras. However, there are a handful of works, mostly from the late Romantic period, in which composers wrote a part for baryton (German) or tenor tuba, (most notably, Holst's Planets Suite, which has many solos for baritone and euphonium) and these are universally played on euphonium, frequently by a trombone player. In addition, the euphonium is sometimes used in older orchestral works as a replacement for its predecessors, such as the ophicleide, or, less correctly, the bass trumpet, or the Wagner tuba, both of which are significantly different instruments, and still in use today. At the bottom of the article are some of the well-known orchestral works in which the euphonium is commonly used (whether or not the composer originally specified it).

Finally, while the euphonium was not historically part of the standard jazz big band or combo, the instrument's technical facility and large range make it well-suited to a jazz solo role, and a jazz euphonium niche has been carved out over the last 40 or so years, largely starting with the pioneer Rich Matteson (see "List of important players" below). The euphonium can also double on a trombone part in a jazz combo. Jazz euphoniums are most likely to be found in tuba-euphonium groups, though modern funk or rock bands occasionally feature a brass player doubling on euphonium, and this trend is growing.

Due to this dearth of performance opportunities, aspiring euphonium players in the United States are in a rather inconvenient position when seeking future employment. Often, college players must either obtain a graduate degree and go on to teach at the college level, or audition for one of the major or regional military service bands. Because these bands are relatively few in number and the number of euphonium positions in the bands is small (2-4 in most service bands), job openings do not occur very often and when they do are highly competitive; before the current slate of openings in four separate bands, the last opening for a euphonium player in an American service band was in May 2004. A career strictly as a solo performer, unaffiliated with any university or performing ensemble, is a very rare sight, but some performers, such as Riki McDonnell, have managed to do it.

In Britain the strongest euphonium players are most likely to find a position in a brass band, but ironically, even though they often play at world-class levels, the members of the top brass bands are in most cases unpaid amateurs. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of brass bands in Britain ranging in standard from world class to local bands. Almost all brass bands in Britain perform regularly, particularly during the summer months. A large number of bands also enter contests against other brass bands of a similar standard. Each band requries two euphoniums (principal and 2nd) and consequently there are considerable opportunities for euphonium players.

Due to limited vocational opportunities, there are a considerable number of relatively serious, quasi-professional avocational euphonium players participating in many higher-caliber unpaid ensembles.

College climate in the United States

Unlike a generation or two ago, most colleges with music programs now offer students the opportunity to major in euphonium. However, due to the small number of euphonium students at most schools (2-4 is common), it is possible, and even likely, that they will study with a professor whose major instrument is not the euphonium. Most often tubas and euphoniums will be combined into a studio taught by one professor, and at small schools they may be grouped with trombones as well, taught by one low brass professor. Dr. Brian Bowman, Demondrae Thurman, and Dr. Marc Dickman serve as the only three full time euphonium college professors in the US, with professors like Matt Tropman and Dr. Stephen Arthur Allen, also primarily euphonium players, teaching as lecturers. Other professors, such as Adam Frey, are adjunct faculty at multiple universities near one another. Usually, of course, universities will require professors in this situation to have a high level of proficiency on all the instruments they teach, and some of the best college euphonium studios are taught by non-euphonium players.

Below are some of the United States's largest and most successful college euphonium studios listed alphabetically, along with their teachers. These studios are likely to be larger than most, and either have one or more graduate students or have sent alumni on to graduate study elsewhere. Their professors are usually accomplished and widely respected artists in their own right, and students from these schools will have been invited either to amateur competitions such as the Leonard Falcone International Tuba and Euphonium Festival or the International Tuba-Euphonium Conference, or to the final rounds of recent military band auditions.

- Arizona State University (Sam Pilafian; tuba)

- Eastern Michigan University (Matt Tropman; Tuba and Euphonium)

- Eastman School of Music (Mark Kellogg; trombone and euphonium)

- New England Conservatory (Norman Bolter; trombone and euphonium)

- Emory University (Adam Frey; euphonium)

- George Mason University (Roger Behrend; euphonium)

- Hartt School of Music (James Jackson; euphonium)

- Indiana University (Daniel Perantoni; tuba, M. Dee Stewart; euphonium)

- Louisiana State University (Joe Skillen; tuba)

- Northwestern University (Rex Martin; tuba and euphonium)

- Ohio University (Jason Roland Smith; tuba and euphonium)

- Pennsylvania State University (Velvet Brown; Tuba and Euphonium)

- Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey (Dr. Stephen Arthur Allen; euphonium)

- Tennessee Technological University (R. Winston Morris; tuba)

- The Ohio State University (James Akins, Tuba and Euphonium)

- University of Alabama (Demondrae Thurman; euphonium)

- Ball State University (Mark Mordue; Tuba and Euphonium)

- University of Arizona (Kelly Thomas; euphonium)

- University of Arkansas (Benjamin Pierce; euphonium and tuba)

- University of Central Florida (Gail Robertson; Euphonium, Trombone, Tuba)

- University of Colorado at Boulder (Michael Dunn; Euphonium and Tuba)

- University of Iowa (John Manning; Euphonium and Tuba)

- University of Georgia (David Zerkel; tuba)

- University of Houston (Phillip Freeman; Euphonium and Bass Trombone)

- University of Michigan (Fritz Kaenzig; tuba)

- University of North Texas (Brian Bowman; euphonium)

- University of Wisconsin–Madison (John Stevens)

Notable euphoniumists

The euphonium world is and has become more crowded than is commonly thought, and there have been many noteworthy players throughout the instrument's history. Traditionally, three main national schools of euphonium playing have been discernible: American, British, and Japanese. Now, euphoniumists are able to learn this specific art in many other countries around the world today.

Below are a select few of the players most famous and influential in their respective countries, and whose contributions to the euphonium world are undeniable, in terms of recordings, commissions, pedagogy, and increased recognition of the instrument. A much more complete list featuring euphoniumists from many other countries as well as younger, lesser-known players can be found at List of euphonium players.

United Kingdom

- Trevor Groom (GUS Band/Virtuosi Band of Great Britain/Kings of Brass) in the opinion of many simply the finest euphonium player ever and the inspiration behind many players of the current generation. Premiered the first Euphonium Concerto (Horovitz, 1972) and the first of many 'serious' new works (Bowen 'Euphonium Music', Gregson 'Symphonic Rhapsody'). Trevor is a euphonium legend and still teaches in the Kettering area.

http://www.facebook.com/?tid=1284615195649&sk=messages#!/group.php?gid=56868919971&ref=ts

- Lyndon Baglin (CWS Manchester Band, Brighouse and Rastrick Band, Stanshawe/Sun Life Band, Fairey Band) Another British legend of the senior generation Lyndon continues to perform at top level. He advised and was an artist for the earliest series of Besson 'Sovereign' euphoniums in the 1970 and recorded the first LP/CD of euphonium solos 'Showcase for the Euphonium' (Saydisc) in the UK in 1975. A true living legend.

http://www.facebook.com/?tid=1284615195649&sk=messages#!/group.php?gid=48327676999&ref=ts

- Dr. Nicholas Childs Welsh soloist, Director of the Black Dyke Band in England

- Dr. Robert Childs, brother of Dr. Nicholas Childs, former soloist with the Black Dyke Band; now Director of Brass Bands at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, Director of the Cory Band

- David Childs, son of Dr. Robert Childs, principal euphonium of the Cory Band

- Steven Mead, English euphonium soloist and professor at the Royal Northern College of Music

- David Thornton, principal euphonium of the Black Dyke Band

- Michael Dodd, principal euphonium of the Grimethorpe Colliery Band

- Derick Kane, principal euphonium of the International Staff Band of The Salvation Army

United States

- Roger Behrend, soloist with the U.S. Navy Band and professor of euphonium at George Mason University

- Dr. Brian Bowman, former soloist with the U.S. Navy Band (1971-75) and U.S. Air Force Band (1976-91); now professor of euphonium at the University of North Texas, co-editor of "Arban's Method for Trombone and Euphonium"

- Adam Frey, American euphonium soloist, Recording Artist, Professor of Euphonium at Georgia State University and Emory University, Founder of the International Euphonium Institute (IEI), more than 70 commissions and arrangements involving the euphonium. Associate Editor of the Euphonium Source Book

- Arthur W. Lehman, 1917-2009, American euphonium soloist known as 'Art', Recording Artist, United States Marine Band, noted euphonium author.

- Harold Brasch, 1916-1984, American euphonium soloist, United States Navy Band (1936-1956); known as "Mr. Euphonium" when radio broadcasts of performances were popular in the U.S. Teacher of Art Lehman and many others. Noted for promoting the British-style euphonium (vs. the traditional American-style baritone), leading to wide-acceptance of the euphonium in bands throughout the U.S. in the 20th century.

- David Werden, former soloist with the U.S. Coast Guard Band, former Instructor of Euphonium at the University of Connecticut, current Instructor of Euphonium at the University of Minnesota, first American to be international Euphonium Player of the Year.

- James E. Jackson III, current U.S. Coast Guard Band Euphonium Soloist and instructor at Hartt School of Music and Professor at the University of Connecticut. First-place winner in the 1995 International T.U.B.A. conference Tuba-Euphonium Quartet competition and first-place winner at the Leonard Falcone International Solo Euphonium Competition in 1994.

- Demondrae Thurman, Demondrae Thurman is quickly becoming one of the most recognized names in a new generation of euphonium soloists. He is a founding member of the highly acclaimed Sotto Voce Tuba Quartet, winner of both international tuba quartet competitions in 1998. Currently, Mr. Thurman teaches at The University of Alabama where he is Assistant Professor of Tuba and Euphonium. Before accepting this position in 2005, he taught at Alabama State University, the University of Montevallo, and Troy State University.

- Aaron VanderWeele is the 2007 recipient of the International Euphonium Player of the Year, only the third American to receive this prestigious honor. He has been the principal euphonium and euphonium soloist of The Salvation Army's New York Staff Band (www.nysb.org) since 1993. He has performed solos on over 20 professional recordings and given solo performances throughout North America, Europe and the Southern Hemisphere. He resides in New Jersey where he is employed as Sales and Marketing Manager for The Salvation Army and is also a private euphonium tutor for developing and established euphoniumists.

- Dr. Stephen Arthur Allen was awarded a Royal Academy Scholarship on euphonium at age 18 by Eric Ball OBE and Geoffrey Brand, director of the Black Dyke Band. He runs a euphonium studio of 6 players and euphonium chamber ensemble at the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey where in 2010 he gave the world premiere of the complete four-movement Gareth Wood 'Euphonium Concerto'.

Japan

- Toru Miura, professor of euphonium at the Kunitachi College of Music; soloist and clinician

Australia

- Matthew van Emmerik; Besson Artist soloist and clinician

- Thom Humphrey; Yamaha Artist soloist and composer

New Zealand

Norway

Canada

- Robert Miller, principal euphonium of the Mississauga Temple Band of The Salvation Army and Weston Silver Band

- David Jackson, co-principal euphonium of the Mississauga Temple Band of The Salvation Army

- Curtis Metcalf, principal euphonium of the Hannaford Street Silver Band

- Steve Pavey, principal euphonium of the Canadian Staff Band of The Salvation Army

- Benjamin Lavoie, Principal euphonium of the Harmonie Vivace

China

Switzerland

- Roland Fröscher [1]

Euphonium literature

The euphonium repertoire consists of solo literature and orchestral or, more commonly, band parts written for the euphonium. Since its invention in 1843, the euphonium has always had an important role in ensembles, but solo literature was slow to appear, consisting of only a handful of lighter solos until the 1960s. Since then, however, the breadth and depth of the solo euphonium repertoire has increased dramatically.

In the current age, there has been a huge number of new commissions and repertoire development and promotion through Steven Mead’s World of the Euphonium Series and the Beyond the Horizon series from Euphonium.com. There has also been a vast number of new commissions by more and more players and a proliferation of large scale Consortium Commissions that are occurring including current ones in 2008 and 2009 organized by Brian Meixner (Libby Larson), Adam Frey (The Euphonium Foundation Consortium), and Jason Ham (David Gillingham).

Upon its invention, it was clear that the euphonium had, compared to its predecessors the serpent and ophicleide, a wide range and had a consistently rich, pleasing sound throughout that range. It was flexible both in tone quality and intonation and could blend well with a variety of ensembles, gaining it immediate popularity with composers and conductors as the principal tenor-voices solo instrument in brass band settings, especially in Britain. It is no surprise, then, that when British composers – some of the same ones who were writing for brass bands – began to write serious, original music for the concert band in the early twentieth century, they used the euphonium in a very similar role. When American composers also began writing for the concert band as its own artistic medium in the 1930s and '40's, they continued the British brass and concert band tradition of using the euphonium as the principal tenor-voiced solo. This is not to say that composers, then and now, valued the euphonium only for its lyrical capabilities. Indeed, examination of a large body of concert band literature reveals that the euphonium functions as a "jack of all trades."

Though the euphonium was, as previously noted, embraced from its earliest days by composers and arrangers in band settings, orchestral composers have, by and large, not taken advantage of this capability. There are, nevertheless, several orchestral works, a few of which are standard repertoire, in which composers have called for instruments, such as the Wagner tuba, for which euphonium is commonly substituted today.

In contrast to the long-standing practice of extensive euphonium use in wind bands and orchestras, there was until approximately forty years ago literally no body of solo literature written specifically for the euphonium, and euphoniumists were forced to borrow the literature of other instruments. Fortunately, given the instrument's multifaceted capabilities discussed above, solos for many different instruments are easily adaptable to performance on the euphonium.

The earliest surviving solo composition written specifically for euphonium or one of its saxhorn cousins is the Concerto per Flicorno Basso (1872) by Amilcare Ponchielli. For almost a century after this, the euphonium solo repertoire consisted of only a dozen or so virtuosic pieces, mostly light in character. However, in the 1960s and '70's, American composers began to write the first of the "new school" of serious, artistic solo works specifically for euphonium. Since then, there has been a virtual explosion of solo repertoire for the euphonium. In a mere four decades, the solo literature has expanded from virtually zero to thousands of pieces. More and more composers have become aware of the tremendous soloistic capabilities of the euphonium, and have constantly "pushed the envelope" with new literature in terms of tessitura, endurance, technical demands, and extended techniques.

Finally, the euphonium has, thanks to a handful of enterprising individuals, begun to make inroads in jazz, pop and other non-concert performance settings.

See also

- Five Valve Euphonium

Notes

- ↑ These may be included for the sake of students who have recently switched from the trumpet, or who play trumpet and are doubling on euphonium. Alternatively, students who learn Euphonium in a British Brass Band may also take advantage of this transposed part.

- ↑ Thus, only on 4-valved, compensating instruments is a full chromatic scale from the pedal range up possible.

References

- ↑ Apel, Willi (1969). Harvard Dictionary of Music. Cambridge:: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1972.. pp. 105–110

- ↑ Werden, David. "Euphonium, Baritone, or ???". http://www.dwerden.com/eu-articles-bareuph.cfm. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- http://lowbrassnmore.com/euponiumhistory.htm Retrieved on 28 January 2008

- http://www.nikknakks.net/euphonium/ Retrieved on 28 January 2008

- http://www.docstoc.com/docs/2198574/HISTORY-OF-THE-BARITONE-AND-THE-EUPHONIUM

External links

- Euphonium.com Focused on the IEI, new repertoire, a forum for the euphonium, and the activities of Adam Frey.

- Euphonium.net Steven Mead's personal website.

- The International Tuba-Euphonium Association, the foremost professional organization for tubists and euphonists.

- Tuba News, a free monthly online publication for tuba and euphonium players.

- Tuba-Euphonium Press, one of the premier publishing houses for new euphonium and tuba music in all genres.

- Brass-Forum.co.uk, a UK based brass discussion forum.

- Tuba-Euphonium Forum, a discussion forum specifically for euphonium and tuba.

- Acoustics of Brass Instruments from Music Acoustics at the University of New South Wales.

- Euphonium Music Guide A listing of original euphonium literature.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.