Euler–Lagrange equation

In calculus of variations, the Euler–Lagrange equation, or Lagrange's equation, is a differential equation whose solutions are the functions for which a given functional is stationary. It was developed by Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler and Italian mathematician Joseph Louis Lagrange in the 1750s.

Because a differentiable functional is stationary at its local maxima and minima, the Euler–Lagrange equation is useful for solving optimization problems in which, given some functional, one seeks the function minimizing (or maximizing) it. This is analogous to Fermat's theorem in calculus, stating that where a differentiable function attains its local extrema, its derivative is zero.

In Lagrangian mechanics, because of Hamilton's principle of stationary action, the evolution of a physical system is described by the solutions to the Euler–Lagrange equation for the action of the system. In classical mechanics, it is equivalent to Newton's laws of motion, but it has the advantage that it takes the same form in any system of generalized coordinates, and it is better suited to generalizations (see, for example, the "Field theory" section below).

Contents |

History

The Euler–Lagrange equation was developed in the 1750s by Euler and Lagrange in connection with their studies of the tautochrone problem. This is the problem of determining a curve on which a weighted particle will fall to a fixed point in a fixed amount of time, independent of the starting point.

Lagrange solved this problem in 1755 and sent the solution to Euler. The two further developed Lagrange's method and applied it to mechanics, which led to the formulation of Lagrangian mechanics. Their correspondence ultimately led to the calculus of variations, a term coined by Euler himself in 1766.[1]

Statement

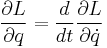

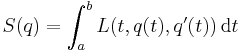

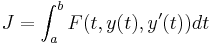

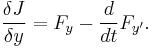

The Euler–Lagrange equation is an equation satisfied by a function, q, of a real argument, t, which is a stationary point of the functional

where:

- q is the function to be found:

- such that q is differentiable, q(a) = xa, and q(b) = xb;

- q′ is the derivative of q:

- TX being the tangent bundle of X (the space of possible values of derivatives of functions with values in X);

- L is a real-valued function with continuous first partial derivatives:

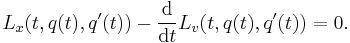

The Euler–Lagrange equation, then, is given by

where Lx and Lv denote the partial derivatives of L with respect to the second and third arguments, respectively.

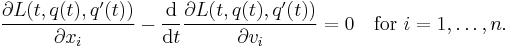

If the dimension of the space X is greater than 1, this is a system of differential equations, one for each component:

-

Derivation of one-dimensional Euler-Lagrange equation The derivation of the one-dimensional Euler–Lagrange equation is one of the classic proofs in mathematics. It relies on the fundamental lemma of calculus of variations.

We wish to find a function

which satisfies the boundary conditions

which satisfies the boundary conditions  ,

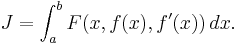

,  , and which extremizes the cost functional

, and which extremizes the cost functionalWe assume that F has continuous first partial derivatives. A weaker assumption can be used, but the proof becomes more difficult.

If f extremizes the cost functional subject to the boundary conditions, then any slight perturbation of f that preserves the boundary values must either increase J (if f is a minimizer) or decrease J (if f is a maximizer).

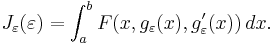

Let gε(x) = f(x) + εη(x) be such a perturbation of f, where η(x) is a differentiable function satisfying η(a) = η(b) = 0. Then define

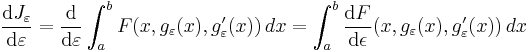

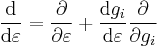

We now wish to calculate the total derivative of J with respect to ε or the first variation of J.

It follows from the total derivative that

So

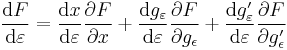

When ε = 0 we have gε = f and since f is an extreme value it follows that

, i.e.

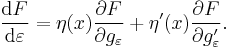

, i.e.The next crucial step is to use integration by parts on the second term, yielding

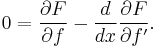

Using the boundary conditions on η, we get that

Applying the fundamental lemma of calculus of variations now yields the Euler–Lagrange equation

-

Alternate derivation of one-dimensional Euler-Lagrange equation Given a functional

on

![C^1([a, b])](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/8a33eba68d7379b365730528445287cb.png) with the boundary conditions

with the boundary conditions  and

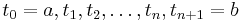

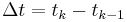

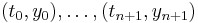

and  , we proceed by approximating the extremal curve by a polygonal line with

, we proceed by approximating the extremal curve by a polygonal line with  segments and passing to the limit as the number of segments grows arbitrarily large.

segments and passing to the limit as the number of segments grows arbitrarily large.Divide the interval

![[a, b]](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/2c3d331bc98b44e71cb2aae9edadca7e.png) into

into  equal segments with endpoints

equal segments with endpoints  and let

and let  . Rather than a smooth function

. Rather than a smooth function  we consider the polygonal line with vertices

we consider the polygonal line with vertices  , where

, where  and

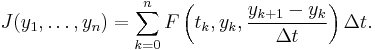

and  . Accordingly, our functional becomes a real function of

. Accordingly, our functional becomes a real function of  variables given by

variables given byExtremals of this new functional defined on the discrete points

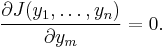

correspond to points where

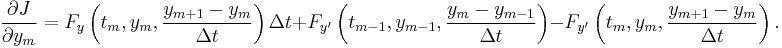

correspond to points whereEvaluating this partial derivative gives that

Dividing the above equation by

gives

givesand taking the limit as

of the right-hand side of this expression yields

of the right-hand side of this expression yieldsThe term

denotes the variational derivative of the functional

denotes the variational derivative of the functional  , and a necessary condition for a differentiable functional to have an extremum on some function is that its variational derivative at that function vanishes.

, and a necessary condition for a differentiable functional to have an extremum on some function is that its variational derivative at that function vanishes.

Examples

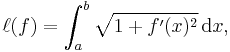

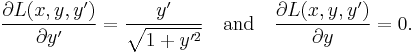

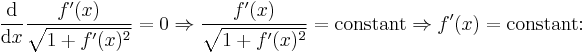

A standard example is finding the real-valued function on the interval [a, b], such that f(a) = c and f(b) = d, the length of whose graph is as short as possible. The length of the graph of f is:

the integrand function being L(x, y, y′) = √1 + y′ ² evaluated at (x, y, y′) = (x, f(x), f′(x)).

The partial derivatives of L are:

By substituting these into the Euler–Lagrange equation, we obtain

that is, the function must have constant first derivative, and thus its graph is a straight line.

Classical mechanics

Basic method

To find the equations of motions for a given system, one only has to follow these steps:

- From the kinetic energy

, and the potential energy

, and the potential energy  , compute the Lagrangian

, compute the Lagrangian  .

. - Compute

.

. - Compute

and from it,

and from it,  . It is important that

. It is important that  be treated as a complete variable in its own right, and not as a derivative.

be treated as a complete variable in its own right, and not as a derivative. - Equate

. This is the Euler–Lagrange equation.

. This is the Euler–Lagrange equation. - Solve the differential equation obtained in the preceding step. At this point,

is treated "normally". Note that the above might be a system of equations and not simply one equation.

is treated "normally". Note that the above might be a system of equations and not simply one equation.

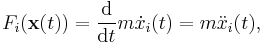

Particle in a conservative force field

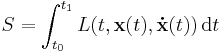

The motion of a single particle in a conservative force field (for example, the gravitational force) can be determined by requiring the action to be stationary, by Hamilton's principle. The action for this system is

where x(t) is the position of the particle at time t. The dot above is Newton's notation for the time derivative: thus ẋ(t) is the particle velocity, v(t). In the equation above, L is the Lagrangian (the kinetic energy minus the potential energy):

where:

- m is the mass of the particle (assumed to be constant in classical physics);

- vi is the i-th component of the vector v in a Cartesian coordinate system (the same notation will be used for other vectors);

- U is the potential of the conservative force.

In this case, the Lagrangian does not vary with its first argument t. (By Noether's theorem, such symmetries of the system correspond to conservation laws. In particular, the invariance of the Lagrangian with respect to time implies the conservation of energy.)

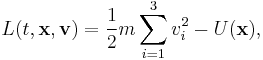

By partial differentiation of the above Lagrangian, we find:

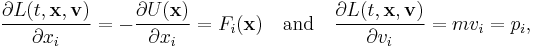

where the force is F = −∇U (the negative gradient of the potential, by definition of conservative force), and p is the momentum. By substituting these into the Euler–Lagrange equation, we obtain a system of second-order differential equations for the coordinates on the particle's trajectory,

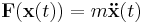

which can be solved on the interval [t0, t1], given the boundary values xi(t0) and xi(t1). In vector notation, this system reads

or, using the momentum,

which is Newton's second law.

Field theory

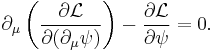

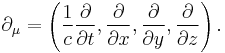

Field theories, both classical field theory and quantum field theory, deal with continuous coordinates, and like classical mechanics, has its own Euler–Lagrange equation of motion for a field,

where

is the field, and

is the field, and is a vector differential operator:

is a vector differential operator:

Note: Not all classical fields are assumed commuting/bosonic variables, (like the Dirac field, the Weyl field, the Rarita-Schwinger field) are fermionic and so, when trying to get the field equations from the Lagrangian density, one must choose whether to use the right or the left derivative of the Lagrangian density (which is a boson) with respect to the fields and their first space-time derivatives which are fermionic/anticommuting objects.

There are several examples of applying the Euler–Lagrange equation to various Lagrangians:

- Dirac equation;

- Proca equation;

- electromagnetic tensor;

- Korteweg–de Vries equation;

- quantum electrodynamics.

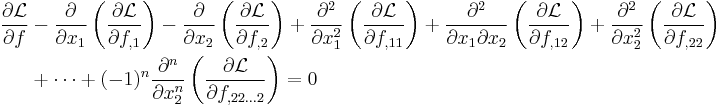

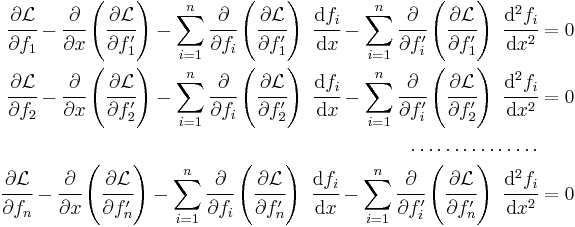

Variations for several functions, several variables, and higher derivatives

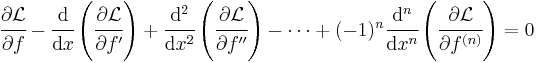

Single function of single variable with higher derivatives

The stationary values of the functional

can be obtained from the Euler-Lagrange equation[2]

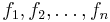

Several functions of one variable

If the problem involves finding several functions ( ) of a single independent variable (

) of a single independent variable ( ) that define an extremum of the functional

) that define an extremum of the functional

then the corresponding Euler-Lagrange equations are[2]

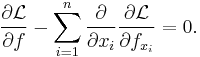

Single function of several variables

A multi-dimensional generalization comes from considering a function on n variables. If Ω is some surface, then

is extremized only if f satisfies the partial differential equation

When n = 2 and  is the energy functional, this leads to the soap-film minimal surface problem.

is the energy functional, this leads to the soap-film minimal surface problem.

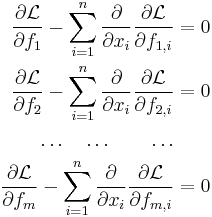

Several functions of several variables

If there are several unknown functions to be determined and several variables such that

the system of Euler-Lagrange equations is[2]

Single function of two variables with higher derivatives

If there is a single unknown function to be determined that is dependent on two variables and their higher derivatives such that

the Euler-Lagrange equation is[2]

Notes

References

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Euler-Lagrange Differential Equation" from MathWorld.

- Calculus of Variations on PlanetMath

- Izrail Moiseevish Gelfand (1963). Calculus of Variations. Dover. ISBN 0-486-41448-5.

- Calculus of Variations at Example Problems.com (Provides examples of problems from the calculus of variations that involve the Euler–Lagrange equations.)

See also

- Lagrangian mechanics

- Hamiltonian mechanics

- Analytical mechanics

- Beltrami identity

![\begin{align}

q \colon [a, b] \subset \mathbb{R} & \to X \\

t & \mapsto x = q(t)

\end{align}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/0163ce2c2f0a79b4da0cb9c704f03985.png)

![\begin{align}

q' \colon [a, b] & \to T_{q(t)}X \\

t & \mapsto v = q'(t)

\end{align}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/6eacf3691f5c195a7be14edd1e08256a.png)

![\begin{align}

L \colon [a, b] \times X \times TX & \to \mathbb{R} \\

(t, x, v) & \mapsto L(t, x, v).

\end{align}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/f318638b3b55baa7d7d62b2a057151f4.png)

![\frac{\mathrm{d} J_\varepsilon}{\mathrm{d} \varepsilon} = \int_a^b \left[\eta(x) \frac{\partial F}{\partial g_\varepsilon} + \eta'(x) \frac{\partial F}{\partial g_\varepsilon'} \, \right]\,dx.](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/f1de58c89b0379e8a58d9f2c2298bfc3.png)

![\frac{\mathrm d J_\varepsilon}{\mathrm d\varepsilon}(0) = \int_a^b \left[ \eta(x) \frac{\partial F}{\partial f} + \eta'(x) \frac{\partial F}{\partial f'} \,\right]\,dx = 0.](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/567e6062fe71e94c8432c261f42c1003.png)

![0 = \int_a^b \left[ \frac{\partial F}{\partial f} - \frac{d}{dx} \frac{\partial F}{\partial f'} \right] \eta(x)\,dx + \left[ \eta(x) \frac{\partial F}{\partial f'} \right]_a^b.](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/97f3e724534d7b0570b283024bde56ac.png)

![0 = \int_a^b \left[ \frac{\partial F}{\partial f} - \frac{d}{dx} \frac{\partial F}{\partial f'} \right] \eta(x)\,dx. \,\!](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/542096431d8f2b7ce1adfd5f70b53ee2.png)

![\frac{\partial J}{\partial y_m \Delta t} = F_y\left(t_m, y_m, \frac{y_{m + 1} - y_m}{\Delta t}\right) - \frac{1}{\Delta t}\left[F_{y'}\left(t_m, y_m, \frac{y_{m + 1} - y_m}{\Delta t}\right) - F_{y'}\left(t_{m - 1}, y_{m - 1}, \frac{y_m - y_{m - 1}}{\Delta t}\right)\right],](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/9f23d8e27c7fe3f2e39b37dc16150762.png)

![I[f] = \int_{x_0}^{x_1} \mathcal{L}(x, f, f', f'', \dots, f^{(n)})~\mathrm{d}x ~;~~

f'�:= \cfrac{\mathrm{d}f}{\mathrm{d}x}, ~f''�:= \cfrac{\mathrm{d}^2f}{\mathrm{d}x^2}, ~

f^{(n)}�:= \cfrac{\mathrm{d}^nf}{\mathrm{d}x^n}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/a502eb7022b03884d406d6f5ef622df6.png)

![I[f_1,f_2, \dots, f_n] = \int_{x_0}^{x_1} \mathcal{L}(x, f_1, f_2, \dots, f_n, f_1', f_2', \dots, f_n')~\mathrm{d}x

~;~~ f_i'�:= \cfrac{\mathrm{d}f_i}{\mathrm{d}x}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/fd54c9b17a87e46c0c24e2e1dc3db939.png)

![I[f] = \int_{\Omega} \mathcal{L}(x_1, \dots , x_n, f, f_{x_1}, \dots , f_{x_n})\, \mathrm{d}\mathbf{x}\,\! ~;~~

f_{x_i}�:= \cfrac{\partial f}{\partial x_i}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/be771dae942a49056cbd7a514103b4b4.png)

![I[f_1,f_2,\dots,f_m] = \int_{\Omega} \mathcal{L}(x_1, \dots , x_n, f_1, \dots, f_m, f_{1,1}, \dots , f_{1,n}, \dots, f_{m,1}, \dots, f_{m,n}) \, \mathrm{d}\mathbf{x}\,\! ~;~~

f_{j,i}�:= \cfrac{\partial f_j}{\partial x_i}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/4fe6b0cb4e2680092795c3f23f6970d7.png)

![\begin{align}

I[f] & = \int_{\Omega} \mathcal{L}(x_1, x_2, f, f_{,1}, f_{,2}, f_{,11}, f_{,12}, f_{,22},

\dots f_{,11\dots 1},\dots, f_{,1\dots 2})\, \mathrm{d}\mathbf{x}\,\! \\

& \qquad \quad

f_{,i}�:= \cfrac{\partial f}{\partial x_i} ~;~~ f_{,ij}�:= \cfrac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_i\partial x_j} ~;~~

f_{,1\dots n}�:= \cfrac{\partial^{n} f}{\partial x_1\dots\partial x_n}

\end{align}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/3c05ca1a08b45431aad578bfb22a9f9c.png)