Estonians

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

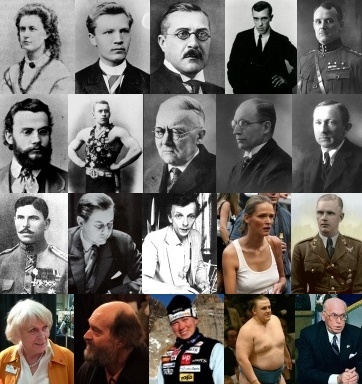

| Top row from left: Lydia Koidula, Juhan Liiv, Artur Kapp, Konrad Mägi, Johan Laidoner Second row from left: Carl Robert Jakobson, Georg Lurich, Ernst Öpik, Jüri Uluots, Anton Hansen Tammsaare Third row from left: Julius Kuperjanov, Paul Keres, Juhan Viiding, Carmen Kass, Alfons Rebane Bottom row from left: Ilon Wikland, Arvo Pärt, Kristina Šmigun-Vähi, Kaido Höövelson, Lennart Meri |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Estonian |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mostly Non-religious, Lutheran Tradition |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Baltic Finns |

Estonians (Estonian: eestlased, previously maarahvas) are a Finnic people closely related to the Finns and inhabiting, primarily, the country of Estonia. The Estonians speak a Finno-Ugric language, known as Estonian. Although Estonia is traditionally grouped as one of the Baltic countries, Estonians are linguistically and ethnically unrelated to the Baltic peoples of Latvia and Lithuania.

Contents |

History

Prehistoric roots

Estonia was first inhabited about 10,000 years ago, just after the Baltic ice lake had retreated from Estonia. While it is not certain what languages were spoken by the first settlers, it is often maintained that speakers of early Finno-Ugric languages related to modern Estonian had arrived in what is now Estonia by about 5000 years ago.[10] Living in the same area for more than 5000 years would put the ancestors of Estonians among the oldest permanent inhabitants in Europe.[11] On the other hand, some recent liguistic estimations suggest that Fenno-Ugrian language arrived around the Baltic Sea considerably later, perhaps during the Early Bronze Age (ca. 1800 BCE).[12][13]

The name "Eesti", or Estonia, is thought to be derived from the word Aestii, the name given by the ancient Germanic peoples to the Baltic peoples living northeast of the Vistula River. The Roman historian Tacitus in 98 A.D. was the first to mention the "Aestii" people, and early Scandinavians called the land south of the Gulf of Finland "Eistland" ("Eistland" is also the current word in Icelandic for Estonia), and the people "eistr". Proto-Estonians (as well as other speakers of the Finnish language group) were also called Chuds (чудь) in Old East Slavic chronicles.

The Estonian language belongs to the Balto-Finnic branch of the Finno-Ugric group of languages, as does the Finnish language. The first book in Estonian was printed in 1525, while the oldest known examples of written Estonian originate in 13th-century chronicles.

National consciousness

Although Estonian national consciousness spread in the course of the 19th century during the Estonian national awakening,[14] some degree of ethnic awareness preceded this development.[15] By the 18th century the self-denomination eestlane spread among Estonians along with the older maarahvas.[16] The Bible was translated in 1739, and the number of books and brochures published in Estonian increased from 18 in the 1750s to 54 in the 1790s. By the end of the century more than a half of adult peasants were able to read. The first university-educated intellectuals identifying themselves as Estonians, including Friedrich Robert Faehlmann (1798–1850), Kristjan Jaak Peterson (1801–22) and Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald (1803–82), appeared in the 1820s. The ruling elites had remained predominantly German in language and culture since the conquest of the early 13th century. Garlieb Merkel (1769–1850), a Baltic German Estophile, was the first author to treat the Estonians as a nationality equal to others and became a source of inspiration for the Estonian national movement, modeled on Baltic German cultural world before the middle of the 19th century. However, in the middle of the century, the Estonians became more ambitious and started leaning toward the Finns as a successful model of national movement and, to some extent, the neighbouring Latvian national movement. By the end of 1860 the Estonians became unwilling to reconcile with German cultural and political hegemony. Before the attempts at Russification in the 1880s, their view of Imperial Russia remained positive.[15]

Estonians have strong ties to the Nordic countries stemming from important cultural and religious influences gained over centuries during Scandinavian and German rule and settlement.[17] Indeed, Estonians consider themselves Nordic rather than Baltic,[18][19] in particular because of a close ethnic and linguistic affinity with the Finns.

Recent developments

From 1945–89, the share of ethnic Estonians in Estonia dropped from 94% to 61%, caused primarily by the deportations organized by the Soviet regime and the Soviet mass immigration program from Russia and other parts of the former USSR into industrial urban areas of Estonia, as well as by wartime emigration and Stalin's mass deportations and executions. The ethnic Estonian population has now risen to 70%.

Most émigré Estonians live in Russia, Finland, Sweden, the U.S., Canada, or other Western countries. In neighboring Latvia, there are about 2,700 ethnic Estonians (1997 census); in Lithuania, the number was 600 in 1989.

1. Kadrina 2. Mihkli 3.Seto 4. Paistu

5.Muhu 6.Karja 7. Tõstamaa 8. Pärnu-Jaagupi

Emigration

During World War II, when Estonia was invaded by the Soviet Army in 1944, large numbers of Estonians fled their homeland on ships or smaller boats over the Baltic Sea. Many refugees who survived the risky sea voyage to Sweden or Germany later moved from there to Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States or Australia. Some of these refugees and their descendants returned to Estonia after the nation regained its independence in 1991.

See also

- List of notable Estonians

- Demographics of Estonia

- List of Estonian Americans

- Estonian national awakening

Notes and references

- ↑ Population of Estonia by ethnic nationality, mother tongue and citizenship

- ↑ Russian census of 2002

- ↑ 29,045±3,999 at 90% confidence interval; "B04003. Total Ancestry Reported". 2008 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. United States Census Bureau. http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DTTable?-mt_name=ACS_2008_1YR_G2000_B04003&-mt_name=ACS_2008_1YR_G2000_B04001&-mt_name=ACS_2008_1YR_G2000_B04002. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ↑ 14,000 Estonian mother tongue speakers in the UK

- ↑ Tilastokeskus: Kieli iän ja sukupuolen mukaan maakunnittain 1990 - 2007

- ↑ 2054.0 Australian Census Analytic Program: Australians' Ancestries (2001 (Corrigendum))

- ↑ "The distribution of the population by nationality and mother tongue". State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. 2001. http://www.ukrcensus.gov.ua/eng/results/nationality_population/nationality_1/s5/?botton=cens_db&box=5.1W&k_t=00&p=20&rz=1_1&rz_b=2_1%20%20%20%20&n_page=2.

- ↑ http://www.pmlp.gov.lv/lv/statistika/dokuments/2009/3ISVN_Latvija_pec_TTB_VPD.pdf

- ↑ CSO - Statistics: Persons usually resident or present in the State on Census Night, classified by place of birth and age group

- ↑ Virpi Laitinena et al. (2002), Y-Chromosomal Diversity Suggests that Baltic Males Share Common Finno-Ugric-Speaking Forefathers, Human Heredity, pages 68-78, [1]

- ↑ Unrepresented Nations and peoples organization By Mary Kate Simmons; p141 ISBN 9789041102232

- ↑ Petri Kallio 2006: Suomalais-ugrilaisen kantakielen absoluuttisesta kronologiasta. — Virittäjä 2006. (With English summary).

- ↑ Häkkinen, Jaakko 2009: Kantauralin ajoitus ja paikannus: perustelut puntarissa. – Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Aikakauskirja 92. http://www.sgr.fi/susa/92/hakkinen.pdf

- ↑ Gellner, Ernest (1996). Do nations have navels? Nations and Nationalism 2.2, 365–70.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Raun, Toivo U. (2003). Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Estonian nationalism revisited. Nations and Nationalism 9.1, 129-147.

- ↑ Ariste, Paul (1956). Maakeel ja eesti keel. Eesti NSV Teaduste Akadeemia Toimetised 5: 117–24.

- ↑ Piirimäe, Helmut. Historical heritage: the relations between Estonia and her Nordic neighbors. In M. Lauristin et al. (eds.), Return to the Western world: Cultural and political perspectives on the Estonian post-communist transition. Tartu: Tartu University Press, 1997.

- ↑ Estonian foreign ministry report, 2004

- ↑ Estonian foreign ministry report, 2002

Further reading

- Petersoo, Pille (January 2007). "Reconsidering otherness: constructing Estonian identity". Nations and Nationalism 13 (1): 117–133. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8129.2007.00276.x. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1469-8129.2007.00276.x.

External links

- Office of the Minister for Population and Ethnic Affairs: Estonians abroad

- From Estonia To Thirlmere (online exhibition)

- Our New Home Meie Uus Kodu: Estonian-Australian Stories (online exhibition)

|

|||||||||||||