Land of Israel

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

|

| Who is a Jew? · Etymology · Culture |

|

God in Judaism (Names)

Principles of faith · Mitzvot (613) Halakha · Shabbat · Holidays Prayer · Tzedakah Brit · Bar / Bat Mitzvah Marriage · Bereavement Philosophy · Ethics · Kabbalah Customs · Synagogue · Rabbi |

|

Ashkenazi · Sephardi · Mizrahi

Romaniote · Italki · Yemenite African · Beta Israel · Bukharan · Georgian • German · Mountain · Chinese Indian · Khazars · Karaim • Krymchaks • Samaritans • Crypto-Jews |

|

Population

|

|

Denominations

Alternative · Conservative

Humanistic · Karaite · Liberal · Orthodox · Reconstructionist Reform · Renewal · Traditional |

|

Timeline · Leaders

Ancient · Kingdom of Judah Temple Babylonian exile Yehud Medinata Hasmoneans · Sanhedrin Schisms · Pharisees Jewish-Roman wars Christianity and Judaism Islam and Judaism Diaspora · Middle Ages Sabbateans · Hasidism · Haskalah Emancipation · Holocaust · Aliyah Israel (history) Arab conflict · Land of Israel Baal teshuva · Persecution Antisemitism (history) |

|

Politics

|

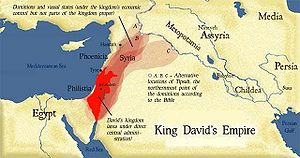

The Land of Israel (Hebrew: אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל Eretz Yisrael) refers to the land in the southern Levant which the Jewish people have since Biblical times regarded as their God-given homeland. Over 3,500 years ago, according to the Bible, the land was promised by God to the descendants of Abraham through his son Isaac[1] and to the Israelites, descendants of Jacob, Abraham's grandson. This land forms part of the Biblical covenant between God and the Jewish people. The most precise geographical borders of the promised land are given in Exodus 23:31, which describes the borders as the Red Sea, the "Sea of the Philistines" i.e the Mediterranean, and the "River" (the Euphrates). References to the land of Israel are also made in the New Testament, for example in Matthew 2:19-21. The actual political boundaries of the land have fluctuated from time to time and the land has been referred to by other names over time. At its maximum extent, during the height of David's united Kingdom of Israel,[2][3] it corresponded approximately to present-day Israel, the Palestinian territories, the western part of Jordan and the southern part of Lebanon; at other times it embraced only the area around Jerusalem.

Contents |

Etymology and biblical roots

The term "Land of Israel" is a direct translation of the Hebrew phrase "ארץ ישראל" (Eretz Yisrael), which is found in the Hebrew Bible. According to Anita Shapira, the term "Eretz Israel" was a holy term, vague as far as the exact boundaries of the territories are concerned but clearly defining ownership.[4]

The name "Israel" first appears in the Bible as the name given by God to the patriarch Jacob (Genesis 32:28), which can be translated as "God contended".[5] The name already occurs in Eblaite and Ugaritic texts as a common name.[6] Commentators differ on the original literal meaning. Some say the name comes from the verb śœarar ("to rule, be strong, have authority over"), thereby making the name mean "God rules" or "God judges".[7] Other possible meanings include "the prince of God" (from the King James Version) or "El fights/struggles".[8] Regardless of the precise meaning of the name, the biblical nation fathered by Jacob thus became the "Children of Israel" or the "Israelites".

The first definition of the promised land (Genesis 15:13-21) calls it "this land". In Genesis 15, this land is promised to Abraham's "descendants", through his son Isaac, while in Deuteronomy 1:8, it is promised explicitly to the Israelites.

A more detailed definition is given in Numbers 34:1-15 for the land explicitly allocated to nine and half of the Israelite tribes after the Exodus. In this passage, the land is called "Land of Canaan". The expression "Land of Israel" is first used in a later book, 1 Samuel 13:19. It is used often in the Book of Ezekiel and also by the Gospel of Matthew.

Dimensions according to the Bible

Biblical borders

The Hebrew Bible provides three somewhat more specific sets of borders, each with a different purpose. The passages where these are defined are Genesis 15:18-21, Numbers 34:1-15 and Ezekiel 47:13-20.

The Borders of the Land - Genesis 15

Genesis 15:18-21 describes what are known as "Borders of the Land" (Gevulot Ha-aretz),[9] which in Jewish tradition defines the extent of the land promised to the descendants of Abraham, through his son Isaac and grandson Jacob.[10] The passage describes the land in terms of the extent of territories of various ancient peoples.

More precise geographical borders are given Exodus 23:31 which describes borders as marked by the Red Sea (see debate below), the "Sea of the Philistines" i.e., the Mediterranean, and the "River," the Euphrates), the traditional furthest extent of the Kingdom of David.[2][11]

Land of Canaan - Numbers 34

Numbers 34:1-15 describes the land allocated to the Israelite tribes after the Exodus. The tribes of Reuben, Gad and half of Manasseh received land east of the Jordan as explained in Numbers 34:14-15. Numbers 34:1-13 provides a detailed description of the borders of the land to be conquered west of the Jordan for the remaining tribes. The region is called "the Land of Canaan" (Eretz Kna'an) in Numbers 34:2 and the borders are known in Jewish tradition as the "borders for those coming out of Egypt". These borders are again mentioned in Deuteronomy 1:6-8, 11:24 and Joshua 1:4.

As the Hebrew Scriptures explain, Canaan was the son of Ham who with his descendents had seized the land from the descendents of Shem according to the Book of Jubilees. Jewish tradition thus refers to the region as Canaan during the period between the Flood and the Israelite settlement. Schweid sees Canaan as a geographical name, and Israel the spiritual name of the land: The uniqueness of the Land of Israel is thus "geo-theological" and not merely climatic. This is the land which faces the entrance of the spiritual world, that sphere of existence that lies beyond the physical world known to us through our senses. This is the key to the land's unique status with regard to prophecy and prayer, and also with regard to the commandments.[12] Thus, the re-naming of this land marks a change in religious status, the origin of the Holy Land concept. Numbers 34:1-13 uses the term Canaan strictly for the land west of the Jordan, but Land of Israel is used in Jewish tradition to denote the entire land of the Israelites. The English expression "Promised Land" can denote either the land promised to Abraham in Genesis or the land of Canaan, although the latter meaning is more common.

Prophetic borders - Ezekiel 47

Ezekiel 47:13-20 provides a definition of borders of land in which the twelve tribes of Israel will live during the final redemption, at the end of days. The borders of the land described by the text in Ezekiel include the northern border of modern Lebanon, eastwards (the way of Hethlon) to Zedad and Hazar-enan in modern Syria; south by southwest to the area of Busra on the Syrian border (area of Hauran in Ezekiel); follows the Jordan River between the West Bank and the land of Gilead to Tamar (Ein Gedi) on the western shore of the Dead Sea; From Tamar to Meribah Kadesh (Kadesh Barnea), then along the Brook of Egypt (see debate below) to the Mediterranean Sea. The territory defined by these borders is divided into twelve strips, one for each of the twelve tribes.

Hence, Numbers 34 and Ezekiel 47 define different but similar borders which include the whole of contemporary Lebanon, both the West Bank and the Gaza Strip and Israel, except for the South Negev and Eilat. Small parts of Syria are also included.

From Dan to Beersheba

The common Biblical phrase used to refer to the territories actually settled by the Israelites (as opposed to military expansions) is "from Dan to Beersheba" (or its variant "from Beersheba to Dan"), which occurs many times in the Bible. It is found in the Biblical verses Judges 20:1, 1 Samuel 3:20, 2 Samuel 3:10, 2 Samuel 17:11, 2 Samuel 24:2, 2 Samuel 24:15, 1 Kings 4:25, 1 Chronicles 21:2, and 2 Chronicles 30:5.

Locating Biblical landmarks

Brook of Egypt

The border with Egypt is given as the Nachal Mitzrayim (Brook of Egypt) in Numbers and Deuteronomy, as well as in Ezekiel. Jewish tradition (as expressed in the commentaries of Rashi and Yehuda Halevi, as well as the Aramaic Targums) understand this as referring to the Nile; more precisely the Pelusian branch of the Nile Delta according to Halevi—a view supported by Egyptian and Assyrian texts. Saadia Gaon identified it as the "Wadi of El-Arish" referring to the Biblical Sukkot near Faiyum. Kaftor Vaferech placed it in the same region which approximates the location of the former Pelusian branch of the Nile. 19th century Bible commentaries understood the identification as a reference to the Wadi of the coastal locality called El-Arish. Easton's however, notes a local tradition that the course of the river had changed and there was once a branch of Nile where today there is a wadi. Biblical minimalists have suggested that the Besor is intended.

Genesis gives the border with Egypt as Nahar Miztrayim -- nahar denotes a large river in Hebrew never a wadi.

Southern and eastern borders

Only the "Red Sea" (Exodus 23:31) and the Euphrates are mentioned to define the southern and eastern borders of the full land promised to the Israelites. The "Red Sea," corresponding to Hebrew Yam Suf was understood in ancient times to be the Erythraean Sea, as reflected in the Septuagint translation. Although the English name "Red Sea" is derived from this name ("Erythraean" derives from the Greek for red), the term denoted all the waters surrounding Arabia—including the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf, not merely the sea lying to the west of Arabia bearing this name in modern English. Thus the entire Arabian peninsula lies within the borders described. Modern maps depicting the region take a reticent view and often leave the southern and eastern borders vaguely defined. The borders of the land to be conquered given in Numbers have a precisely defined eastern border which included the Arabah and Jordan.

Variability of the boundaries

Deuteronomy 19:8 indicates a certain fluidity of the borders of the promised land when it refers to the possibility that God would "enlarge your borders." This expansion of territory means that Israel would receive "all the land he promised to give to your fathers," which implies that the settlement actually fell short of what was promised. According to Jacob Milgrom, Deuteronomy refers to a more utopian map of the promised land, whose eastern border is the wilderness rather than the Jordan.[13]

Paul R. Williamson notes that a "close examination of the relevant promissory texts" supports a "wider interpretation of the promised land" in which it is not "restricted absolutely to one geographical locale." He argues that "the map of the promised land was never seen permanently fixed, but was subject to at least some degree of expansion and redefinition."[14]

Historical kingdoms

Of the many historical kingdoms in the region, only the Hasmonean Kingdom and the Herodian dynasty ruled a political unit that fulfills the description, "From Dan to Beersheva."[15]

The historical dimensions of the Davidic kingdom remain uncertain. According to Duke University professor of archaeology Carol Meyers, the scholarly consensus is that the kingdom of Saul encompassed the hill country from Dan (the source of the Jordan River) to Beersheva, and both sides of the Jordan, but not the coastal plain. The kingdoms of David and Solomon also included areas to the south and east of the Dead Sea and Jordan River, and an inland area in the north that reaches north of modern Damascus.[16]

Jewish law

According to Jewish law (halakha), some religious laws only apply to Jews living in the Land of Israel and some areas in Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria (which are thought to be part of Biblical Israel). These include agricultural laws such as the Shmita (Sabbatical year); tithing laws such as the Maaser Rishon (Levite Tithe), Maaser sheni, and Maaser ani (poor tithe); charitable practices during farming, such as pe'ah; and laws regarding taxation. One popular source lists 26 of the 613 mitzvot as contingent upon the Land of Israel.[17]

Many of the laws which applied in ancient times are applied in the modern State of Israel; others have not been revived, since the State of Israel does not adhere to traditional Jewish law. However, certain parts of the current territory of the State of Israel, such as the Arabah, are considered by some authorities to be outside the Land of Israel for purposes of Jewish law. According to these authorities, the religious laws do not apply there.[18]

According to some Jewish religious authorities, every Jew has an obligation to dwell in the Land of Israel and may not leave except for specifically permitted reasons (e.g., to get married).[19] There are also many laws dealing with how to treat the land. The laws apply to all Jews, and the giving of the land itself in the covenant, applies to all Jews, including converts.[20]

Traditional Jewish interpretation, and that of most Christian commentators, define Abraham's descendants only as Abraham's seed through his son Isaac and his grandson Jacob.[10][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30] Johann Friedrich Karl Keil is less clear, as he states that the covenant is through Isaac, but notes that Ishmael's descendants have held much of that land through time.[31]

From the Kingdom of Judah to the present

After the fall of the ancient Kingdom of Judah the land passed into foreign rule, apart from brief periods, under the following powers:

- 586–539 BC: Babylonian Empire

- 539–332 BC: Persian Empire

- 332–305 BC: Empire of Alexander the Great

- 305–198 BC: Ptolemaics

- 198–141 BC: Seleucids

- 141–37 BC: The Hasmonean kingdom in Israel established by the Maccabees, after 63 BC under Roman supremacy

- 37 BC–70 AD: Herodian Dynasty ruling Judea under Roman supremacy (37 BC–6 AD and 41–44 AD), interchanging with direct Roman rule (6–41 CE and 44–66 AD). This ended in the first Jewish Revolt of 66–73 AD, which saw the Temple destroyed in 70 AD.

- 6 AD Census of Quirinius and establishment of Roman Iudaea Province

- 70–395: province of Roman Empire first called Judea, after 135 called Palaestina by the Romans to spite the Jews following the Second Jewish Revolt (The Bar Kokhba Revolt). In 395 the Roman Empire is split into a Western and an Eastern part.

- 395–638: Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire

- 638–1099: Arab Caliphates and subject rulers

- 1099–1187: Crusader states, most notably the Kingdom of Jerusalem

- 1187–1260: dominated by the Ayyubids of Egypt and Damascus

- 1260–1516: dominated by the Mamluks of Egypt

- 1516–1917: Ottoman Turks, having previously conquered the Byzantine Empire in 1453

- 1918–1948: British mandate of Palestine under, first, League of Nations, then, successor United Nations; the Emirate of Trans-Jordan was separated from the rest of Palestine in 1922, and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan became independent upon the expiration of the League of Nations Mandate in 1946.

- May 1948–June 1967: Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, for the Old City of Jerusalem and the larger part of the area; State of Israel for a smaller strip of land in the west

- June 1967 to present: State of Israel

Modern history

Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities.[32] Nonetheless, during two millennia of exile and with an almost continuous small settlement, a strong sense of bondedness exists throughout this tradition, expressed in terms of people-hood; from the very beginning, this concept was identified with that ancestral Biblical land or, to use the traditional religious and modern Hebrew term, Eretz Yisrael. Religiously the area was seen broadly as a land of destiny, and always with hope for some form of redemption and return. It was later seen as a national home and refuge, intimately related to that traditional sense of people-hood, and meant to show continuity that this land was always seen as central to Jewish life, in theory if not in practice.[33] Having already used another religious term of great importance, Zion, to coin the name of their movement,[34] the term was considered appropriate for the secular Jewish political movement of Zionism to adopt at the turn of the 20th century; it was used to refer to their proposed national homeland in the area then controlled by the Ottoman Empire and generally known as the Holy Land or Palestine.[35] Different geographic and political definitions for the ‘Land of Israel’ later developed among competing Zionist ideologies during their nationalist struggle. These differences relate to the importance of the idea and its land, as well as the internationally recognized borders of the State of Israel and the Jewish State’s secure and democratic existence. Many current governments, politicians and commentators question these differences.

When Israel was founded in 1948, the majority Labor leadership, which governed for three decades after independence, accepted the partition of the previous British Mandate of Palestine into independent Jewish and Arab states as a pragmatic solution to the political and demographic issues of the territory, with the description Land of Israel applying to the territory of the State of Israel within the Green Line. The then opposition revisionists, who evolved into today's Likud party, however, regarded the rightful Land of Israel as Eretz Yisrael Ha-Shlema (literally, the whole Land of Israel), which came to be referred to as Greater Israel.[36] Joel Greenberg, writing in The New York Times relates subsequent events this way:[36]

The seed was sown in 1977, when Menachem Begin of Likud brought his party to power for the first time in a stunning election victory over Labor. A decade before, in the 1967 war, Israeli troops had in effect undone the partition accepted in 1948 by overrunning the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Ever since, Mr. Begin had preached undying loyalty to what he called Judea and Samaria (the West Bank lands) and promoted Jewish settlement there. But he did not annex the West Bank and Gaza to Israel after he took office, reflecting a recognition that absorbing the Palestinians could turn Israel it into a binational state instead of a Jewish one.

Following the Six Day War in 1967, the 1977 elections and the Oslo Accords, the term Eretz Israel became increasingly associated with right-wing expansionist groups who sought to conform the borders of the State of Israel with the biblical Eretz Yisrael.[37] Nevertheless, it remains the standard term for referring to the region prior to the establishment of the state, and ultra-Orthodox Jews who are opposed to the State of Israel still refer to the region as Eretz Yisrael.

British Mandate

The biblical concept of Eretz Israel, and its re-establishment as a state in the modern era, was a basic tenet of the original Zionist program. This program however, saw little success until the British acceptance of ‘the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people’ in the Balfour Declaration of 1917. The subsequent British occupation and acceptance of the British Mandate of Palestine by the League of Nations, advanced the Zionist cause. Chaim Weizmann, as leader of the Zionist delegation, at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference presented the Zionist Statement on February 3. Among other things, he presented a plan for development together with a map of the proposed homeland. The statement noted the Jewish historical connection with Eretz Israel. It also declared the Zionist’s proposed borders and resources “essential for the necessary economic foundation of the country” including “the control of its rivers and their headwaters”. These borders included present day Israel, the occupied territories, western Jordan, southwestern Syria and southern Lebanon "in the vicinity south of Sidon".[38]

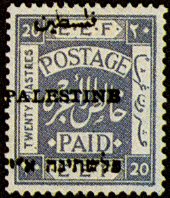

During the Mandate, the name Eretz Yisrael (abbreviated א״י Aleph-Yod), was part of the official name of the territory, when written in Hebrew. The official name "(פלשתינה (א״י" (Palestina E"Y) was also minted on the Mandate coins and early stamps (pictured). Some in the government of the British Mandate of Palestine wanted the name to be פלשתינה (Palestina) while the Yishuv wanted ארץ ישראל (Eretz Yisrael). The compromise eventually achieved was that the initials א"י would be written in brackets whenever פלשתינה is written[39]. Consequently, in 20th century political usage, the term "Land of Israel" usually denotes only those parts of the land which came under the British mandate, i.e. the land currently controlled by the State of Israel, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip, and sometimes also Transjordan (now the Kingdom of Jordan)[40].

Declaration of Independence of Israel

The Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel commences by drawing a direct line from Biblical times to the present:

On 29 November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution calling for the establishment of a Jewish State in Eretz-Israel; the General Assembly required the inhabitants of Eretz-Israel to take such steps as were necessary on their part for the implementation of that resolution. This recognition by the United Nations of the right of the Jewish people to establish their State is irrevocable.

The laws of the State of Israel make it the homeland of all people of Jewish ancestry.

Usage in Israeli politics

Early government usage of the term, following Israel's establishment, continued the historical link and possible Zionist intentions. Twice in official state documents David Ben Gurion, announced that the state was created "in a part of our small country"[41] and "in only a portion of the Land of Israel."[42] He later noted that "the creation of the new State by no means derogates from the scope of historic Eretz Israel."[43]

Herut and Gush Emunim were amongst the first Israeli political parties basing their land policies on the Biblical narrative discussed above. They attracted attention following the capture of additional territory in the 1967 Six-Day War. They argue that the West Bank should be annexed permanently to Israel for both ideological and religious reasons. This position is in conflict with the basic “land for peace” settlement formula included in UN242. The Likud party, in its platform, supports maintaining Jewish settlement communities in the West Bank and Gaza as the territory is considered part of the historical land of Israel.[44] In her 2009 bid for Prime Minister, Kadimah leader Tzipi Livni used the expression, noting, “we need to give up parts of the Land of Israel,” in exchange for peace with the Palestinians and to maintain Israel as a Jewish state; this drew a clear distinction with the position of her Likud rival and winner, Benjamin Netanyahu.[45]

Usage by Palestinians

In its 1988 charter, Hamas claims that After Palestine, the Zionists aspire to expand from the Nile to the Euphrates.[46] The same year, Yasser Arafat voiced the same accusation at the United Nations, the so-called 10 Agorot controversy.[47] About Arafat, Rubinstein writes : he used to repeat the claim that a map of Israel, extending from the Nile to the Euphrates, hangs on the Knesset wall. He even saw the blue stripes in the Israeli flag as a symbol that the Egyptian and Iraqi rivers are the borders for the Zionist state's expansionist aspirations.[48]

See also

- History of the Middle East

- History of Palestine

- History of Israel

- History of the Jews in the Land of Israel

- Holy Land

- Promised land

- Canaan

- Greater Israel

- Jewish history

- Masoretic text

- List of Jewish leaders in the Land of Israel

Notes

- ↑ Albert Barnes Notes on the Bible - Genesis 15

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Stuart, Douglas K., Exodus, B&H Publishing Group, 2006, p. 549

- ↑ Tyndale Bible Dictionary, Walter A. Elwell, Philip Wesley Comfort, Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., 2001, p. 984

- ↑ Anita Shapira, 1992, 'Land and Power', ISBN 0-19-506104-7, p. ix

- ↑ Mike Campbell, Behind the Name, entry Israel

- ↑ Michael G. Hasel, Domination and Resistance: Egyptian Military Activity in the Southern Levant, Brill, 1998

- ↑ Hamilton 1995, p. 334

- ↑ Wenham 1994, pp. 296–297

- ↑ Kol Torah, vol. 13, no. 9, Torah Academy of Bergen County, Nov 8, 2003

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 See 6th and 7th portion commentaries by Rashi

- ↑ Tyndale Bible Dictionary, Walter A. Elwell, Philip Wesley Comfort, Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., 2001, p. 984

- ↑ The Land of Israel: National Home Or Land of Destiny, By Eliezer Schweid, Translated by Deborah Greniman, Published 1985 Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, ISBN 0-8386-3234-3, p.56.

- ↑ Jacob Milgrom, Numbers (JPS Torah Commentary; Philadelphia: JPS, 1990), 502.

- ↑ Paul R. Williamson, "Promise and Fulfilment: The Territorial Inheritance," in Philip Johnston and Peter Walker (eds.), The Land of Promise: Biblical, Theological and Contemporary Perspectives (Leicester: Apollos, 2000), 20-21.

- ↑ A history of Palestine: from the Ottoman conquest to the founding of the state of Israel, Gudrun Krämer, Princeton University Press, 2008, p. 12

- ↑ Carol Meyers, The Early Monarcny, Chapter 5, The Oxford History of the Biblical World, ed. Michael Coogan, Oxford University Press, 1998, pp. 165ff. map on p. 167.

- ↑ p.xxxv, R. Yisrael Meir haKohen (Chofetz Chayim), The Concise Book of Mitzvoth. This version of the list was prepared in 1968.

- ↑ http://www.ohryerushalayim.org.il/halacha_topic.php?id=59 Yeshivat Ohr Yerushalayim, Shmita

- ↑ The Ramban's addition to the Rambam's Sefer HaMitzvot.

- ↑ Ezekiel 47:21 "You are to distribute this land among yourselves according to the tribes of Israel. 22 You are to allot it as an inheritance for yourselves and for the aliens who have settled among you and who have children. You are to consider them as native-born Israelites; along with you they are to be allotted an inheritance among the tribes of Israel. 23 In whatever tribe the alien settles, there you are to give him his inheritance," declares the Sovereign LORD.

- ↑ Edersheim Bible History - Bk. 1, Ch. 10

- ↑ Edersheim Bible History - Bk. 1, Ch. 13

- ↑ Albert Barnes Notes on the Bible - Genesis 15

- ↑ Genesis - Chapter 15 - Verse 13 - The New John Gill Exposition of the Entire Bible on StudyLight.org

- ↑ Parshah In-Depth - Lech-Lecha

- ↑ http://www.bible.org/qa.php?qa_id=496

- ↑ Reformed Answers: Ishmael and Esau

- ↑ The Promises to Isaac and Ishmael

- ↑ God Calls Abram Abraham

- ↑ Nigeriaworld Feature Article - The Abrahamic Covenant: Its scope and significance - A commentary on Dr. Malcolm Fabiyi’s essay

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=F6NkmPGJKvIC&pg=PA216&lpg=PA264&dq=%22keil%22+%2Bishmael&source=web&ots=-wS9DKAoyP&sig=b5eH0qITGDMpRTMAOi1uYj2JxXQ&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result#PPA224,M1

- ↑ Solomon Zeitlin, The Jews. Race, Nation, or Religion? (Philadelphia: Dropsie College Press, 1936). Cited in, Edelheit and Edelheit, History of Zionism: A Handbook and Dictionary

- ↑ Hershel Edelheit and Abraham J. Edelheit, History of Zionism: A Handbook and Dictionary, Westview Press, 2000. p 3.

- ↑ De Lange, Nicholas, An Introduction to Judaism, Cambridge University Press (2000), p. 30. ISBN 0-521-46624-5. The term "Zionism" was derived from the word Zion, and coined by Austrian Nathan Birnbaum, in his journal Selbstemanzipation (Self Emancipation) in 1890.

- ↑ Jewish Virtual Library: The First Zionist Congress and the Basel Program

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 The World: Pursuing Peace; Netanyahu and His Party Turn Away from 'Greater Israel'

- ↑ Raffaella A. Del Sarto, Israel’s Contested Identity and the Mediterranean, The territorial-political axis: Eretz Israel versus Medinat Israel, p.8

Reflecting the traditional divisions within the Zionist movement, this axis invokes two concepts, namely Eretz Israel, i.e. the biblical ‘Land of Israel’, and Medinat Israel, i.e. the Jewish and democratic State of Israel. While the concept of Medinat Israel dominated the first decades of statehood in accordance with the aspirations of Labour Zionism, the 1967 conquest of land that was part of ‘biblical Israel’ provided a material basis for the ascent of the concept of Eretz Israel. Expressing the perception of rightful Jewish claims on ‘biblical land’, the construction of Jewish settlements in the conquered territories intensified after the 1977 elections, which ended the dominance of the Labour Party. Yet as the first Intifada made disturbingly visible, Israel’s de facto rule over the Palestinian population created a dilemma of democracy versus Jewish majority in the long run. With the beginning of Oslo and the option of territorial compromise, the rift between supporters of Eretz Israel and Medinat Israel deepened to an unprecedented degree, the assassination of Prime Minister Rabin in November 1995 being the most dramatic evidence.

- ↑ Zionist Organization Statement on Palestine, Paris Peace Conference, (February 3, 1919)

- ↑ League of Nations, Permanent Mandate Commission, Minutes of the Ninth Session (Arab Grievances), Held at Geneva from June 8th to 25th, 1926

- ↑ Israel's declaration of independence says "the British Mandate over Eretz Yisrael, and the Israeli law uses the term Eretz Yisrael to denote the territory subject directly to the British Mandate law, e.g. Article 11 of the "Government and Law Ordinance 1948" issued by Israel's Provisional State Council.

- ↑ State of Israel, Government Yearbook, 5712 (1951(1952), Introduction p. x.

- ↑ State of Israel, Government Yearbook, 5713 (1952), Introduction p. 15.

- ↑ State of Israel, Government Yearbook. 5716 (1955), p. 320.

- ↑ Likud - Platform, www.knesset.gov.il, http://www.knesset.gov.il/elections/knesset15/elikud_m.htm, retrieved 2008-09-04

- ↑ Heller, Aaron (2009-02-17), accessdate = 2010-02-9 Livni: Give up parts of 'Land of Israel', Associated Press, http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/livni-give-up-parts-of-land-of-israel/article972659/ accessdate = 2010-02-9

- ↑ Hamas Charter, www.mideastweb.org, http://www.mideastweb.org/hamas.htm, retrieved 2009-01-21

- ↑ Pipes, Daniel (1994-03), Imperial Israel: The Nile-to-Euphrates Calumny, www.danielpipes.org, http://www.danielpipes.org/article/247, retrieved 2009-01-21

- ↑ Rubinstein, Danny (1995-09-19), "DOES HE BELIEVE HIS OWN STORIES?", Ha'aretz available online at www.mfa.gov.il

-

- Genesis 15:18-21

-

- In that day the Lord made a covenant with Abram, saying: ‘Unto thy seed have I given this land, from the river of Egypt unto the great river, the river Euphrates; the Kenite, and the Kenizzite, and the Kadmonite, and the Hittite, and the Perizzite, and the Rephaim, and the Amorite, and the Canaanite, and the Girgashite, and the Jebusite.’

-

- Exodus 23:31

-

- And I will set thy border from the Red Sea even unto the sea of the Philistines, and from the wilderness unto the River; for I will deliver the inhabitants of the land into your hand; and thou shalt drive them out before thee.

-

- Numbers 34:1-15

-

- And the Lord spoke unto Moses, saying: ‘Command the children of Israel, and say unto them: When ye come into the land of Canaan, this shall be the land that shall fall unto you for an inheritance, even the land of Canaan according to the borders thereof. Thus your south side shall be from the wilderness of Zin close by the side of Edom, and your south border shall begin at the end of the Salt Sea eastward; and your border shall turn about southward of the ascent of Akrabbim, and pass along to Zin; and the goings out thereof shall be southward of Kadesh-barnea; and it shall go forth to Hazar-addar, and pass along to Azmon; and the border shall turn about from Azmon unto the Brook of Egypt, and the goings out thereof shall be at the Sea. And for the western border, ye shall have the Great Sea for a border; this shall be your west border. And this shall be your north border: from the Great Sea ye shall mark out your line unto mount Hor; from mount Hor ye shall mark out a line unto the entrance to Hamath; and the goings out of the border shall be at Zedad; and the border shall go forth to Ziphron, and the goings out thereof shall be at Hazar-enan; this shall be your north border. And ye shall mark out your line for the east border from Hazar-enan to Shepham; and the border shall go down from Shepham to Riblah, on the east side of Ain; and the border shall go down, and shall strike upon the slope of the sea of Chinnereth eastward; and the border shall go down to the Jordan, and the goings out thereof shall be at the Salt Sea; this shall be your land according to the borders thereof round about.’ And Moses commanded the children of Israel, saying: ‘This is the land wherein ye shall receive inheritance by lot, which the Lord hath commanded to give unto the nine tribes, and to the half-tribe; for the tribe of the children of Reuben according to their fathers’ houses, and the tribe of the children of Gad according to their fathers’ houses, have received, and the half-tribe of Manasseh have received, their inheritance; the two tribes and the half-tribe have received their inheritance beyond the Jordan at Jericho eastward, toward the sun-rising.’

-

- Deuteronomy 1:6-8

-

- The Lord our God spoke unto us in Horeb, saying: ‘Ye have dwelt long enough in this mountain; turn you, and take your journey, and go to the hill-country of the Amorites and unto all the places nigh thereunto, in the Arabah, in the hill-country, and in the Lowland, and in the South, and by the sea-shore; the land of the Canaanites, and Lebanon, as far as the great river, the river Euphrates. Behold, I have set the land before you: go in and possess the land which the Lord swore unto your fathers, to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob, to give unto them and to their seed after them.’

-

- Deuteronomy 11:24

-

- Every place whereon the sole of your foot shall tread shall be yours: from the wilderness, and Lebanon, from the river, the river Euphrates, even unto the hinder sea shall be your border.

-

- Joshua 1:4

-

- From the wilderness, and this Lebanon, even unto the great river, the river Euphrates, all the land of the Hittites, and unto the Great Sea toward the going down of the sun, shall be your border.

A sequence from the Book of Ezekiel provides a vision of borders in end times of a smaller region allocated to the 12 tribes in equal divisions west of the Jordan.

-

- Ezekiel 47:13-20

-

- Thus saith the Lord God: ‘This shall be the border, whereby ye shall divide the land for inheritance according to the twelve tribes of Israel, Joseph receiving two portions. And ye shall inherit it, one as well as another, concerning which I lifted up My hand to give it unto your fathers; and this land shall fall unto you for inheritance. And this shall be the border of the land: on the north side, from the Great Sea, by the way of Hethlon, unto the entrance of Zedad; Hamath, Berothah, Sibraim, which is between the border of Damascus and the border of Hamath; Hazer-hatticon, which is by the border of Hauran. And the border from the sea shall be Hazar-enon at the border of Damascus, and on the north northward is the border of Hamath. This is the north side. And the east side, between Hauran and Damascus and Gilead, and the land of Israel, by the Jordan, from the border unto the east sea shall ye measure. This is the east side. And the south side southward shall be from Tamar as far as the waters of Meriboth-kadesh, to the Brook, unto the Great Sea. This is the south side southward. And the west side shall be the Great Sea, from the border as far as over against the entrance of Hamath. This is the west side.

Further reading

- Keith, Alexander. The Land of Israel: According to the Covenant with Abraham, with Isaac, and Jacob, W. Whyte & Co, 1844.

- Schweid, Eliezer. The Land of Israel: National Home Or Land of Destiny, translated by Deborah Greniman, Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 1985. ISBN 0-8386-3234-3

- Sedykh, Andreĭ. This Land of Israel, Macmillan, 1967.

- Stewart, Robert Laird. The Land of Israel, Revell, 1899.

- John P. McTernan, As America Has Done to Israel, Whitaker House Publishers, 2008. ISBN 978-1-60374-038-8

|

|||||||

|

|||||