Epistle to the Ephesians

The Epistle of Paul to the Ephesians, usually referred to simply as Ephesians, is the tenth book of the New Testament. Its authorship has traditionally been credited to Paul, but it is now widely accepted by critical scholarship to be "deutero-Pauline," that is, written in Paul's name by a later author strongly influenced by Paul's thought.[1][2][3][4] Bible scholar Raymond E. Brown asserts that about 80% of critical scholarship judges that Paul did not write Ephesians.[5]:p.47, and Perrin and Duling[6] say that of six authoritative scholarly references, "four of the six decide for pseudonymity, and the other two (PCB and JBC) recognize the difficulties in maintaining Pauline authorship. Indeed, the difficulties are insurmountable."

Contents |

Theme

The theme of Ephesians “the Church, the Body of Christ.”

As a prisoner for the Lord, then, I urge you to live a life worthy of the calling you have received. Be completely humble and gentle; be patient, bearing with one another in love. Make every effort to keep the unity of the Spirit through the bond of peace.

The Church is to maintain the unity in practice which Christ has brought about positionally.” According to New Testament scholar Daniel Wallace, the theme may be stated pragmatically as “Christians, get along with each other! Maintain the unity practically which Christ has effected positionally by his death.”[7]

Composition

According to tradition, Paul of Tarsus wrote this letter while he was in prison in Rome (around AD 62). This would be about the same time as the Epistle to the Colossians (which in many points it resembles) and the Epistle to Philemon. However, as noted above, most critical scholars have questioned the authorship of the letter, and suggest it may have been written between AD 80 and 100.[1][2][3]

Authenticity

The first verse in the letter, according to the late manuscripts used in most English translations, reads, "Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God, To the saints in Ephesus, the faithful in Christ Jesus." (Eph. 1:1 NIV). Hence, the letter identifies Paul as its author, and these manuscripts designate the Ephesian church as its recipient. Ephesians is found in the two earliest canons, and many of the early Church Fathers (including Clement of Rome, Ignatius, Hermas, and Polycarp) support Paul's authorship. However, there are a few problems with this traditional position, including:

- The earliest and best known manuscripts omit the words "in Ephesus", rendering the phrase simply as "to the saints ... the faithful in Christ Jesus" (NIV alternative translation).

- The letter lacks any references to people in Ephesus, or any events Paul experienced there.

- Phrases such as "ever since I heard about your faith"[1:15] seem to indicate that the writer has no firsthand knowledge of his audience. Yet the book of Acts records that Paul spent a significant amount of time with the church in Ephesus, and in fact was one of its founders.

There are four main theories in Biblical scholarship that address the question of Pauline authorship.[8]

- The traditionalist view that the epistle is written by Paul is supported by scholars that include Ezra Abbot, Asting, Gaugler, Grant, Harnack, Haupt, Fenton John Anthony Hort, Klijn, Johann David Michaelis, A. Robert, and André Feuillet, Sanders, Schille, Brooke Foss Westcott, and Theodor Zahn . For a thorough defense of the Pauline authorship of Ephesians, see Ephesians: An Exegetical Commentary by Harold W. Höhner, pp 2–61.[9]

- A second position suggests that Ephesians was dictated by Paul with interpolations from another author. Some of the scholars that espouse this view include Albertz, Benoit, Cerfaux, Goguel, Harrison, H. J. Holtzmann, Murphy O'Conner, and Wagenfuhrer.

- As noted above, most critical scholars think it improbable that Paul authored Ephesians at all. Among this group are Allan, Beare, Brandon, Bultmann, Conzelmann, Dibelius, Goodspeed, Kilsemann, J. Knox, W.L. Knox, Kümmel, K and S Lake, Marxsen, Masson, Mitton, Moffatt, Nineham, Pokorny, Schweizer, and J. Weiss.

- Still other scholars suggest there is a lack of conclusive evidence. Some of this group are Cadbury, Julicher, McNeile, and Williams.

The lack of any internal references to Ephesus in the early manuscripts led Marcion, a second-century heretical Gnostic who created the first New Testament canon, to believe that the letter was actually addressed to the church at Laodicea. The view is not uncommon in later traditions either, considering that the content of the letter seems to suggest a similar socio-critical context to the Laodicean church mentioned in the Revelation of John.

Place, date, and purpose of the writing of the letter

Most English translations indicate that the addressees are 'the saints who are in Ephesus' (1:1), but the words 'in Ephesus' are not found in the earliest and best Greek manuscripts of this letter. Most textual experts think that the words were not in the letter originally but were added by a scribe after it had already been in circulation for a time.[1]

If Paul was the author of the letter, then it was probably written from Rome during Paul's first imprisonment ( 3:1; 4:1; 6:20), and probably soon after his arrival there in the year 62, four years after he had parted with the Ephesian elders at Miletus. However, scholars who dispute Paul's authorship date the letter to between 70-170.[3] In the latter case, the possible location of the authorship could have been within the church of Ephesus itself. Ignatius of Antioch himself seemed to be very well versed in the epistle to the Ephesians, and mirrors many of his own thoughts in his own epistle to the Ephesians.[3]

The major theme of the letter is the unity and reconciliation of the whole of creation through the agency of the Church and, in particular, its foundation in Christ as part of the will of the Father.

In the Epistle to the Romans, Paul writes from the point of view of the demonstration of the righteousness of God—his covenant faithfulness and saving justice—in the gospel; the author of Ephesians writes from the perspective of union with Christ, who is the head of the true church.

Outline

Ephesians contains:

- 1:1,2. The greeting

- 1:3–2:10. A general account of the blessings that the gospel reveals. This includes the source of these blessings, the means by which they are attained, the reason they are given, and their final result. The whole of the section 1:3-23 consists in the original Greek of just two lengthy and complex sentences ( 1:3-14,15-23). It ends with a fervent prayer for the further spiritual enrichment of the Ephesians.

- 2:11–3:21. A description of the change in the spiritual position of Gentiles as a result of the work of Christ. It ends with an account of how Paul was selected and qualified to be an apostle to the Gentiles, in the hope that this will keep them from being dispirited and lead him to pray for them.

- 4:1–16. A chapter on unity in the midst of the diversity of gifts among believers.

- 4:17–6:9. Instructions about ordinary life and different relationships.

- 6:10–24. The imagery of spiritual warfare (including the metaphor of the Armor of God), the mission of Tychicus, and valedictory blessings.

Founding of the church at Ephesus

Paul's first and hurried visit for the space of three months to Ephesus is recorded in Acts 18:19–21. The work he began on this occasion was carried forward by Apollos[18:24-26] and Aquila and Priscilla. On his second visit early in the following year, he remained at Ephesus "three years," for he found it was the key to the western provinces of Asia Minor. Here "a great door and effectual" was opened to him,[1 Cor 16:9] and the church was established and strengthened by his diligent labours there.[Acts 20:20,31] From Ephesus the gospel spread abroad "almost throughout all Asia."[19:26] The word "mightily grew and prevailed" despite all the opposition and persecution he encountered.

On his last journey to Jerusalem, the apostle landed at Miletus and, summoning together the elders of the church from Ephesus, delivered to them a farewell charge,[20:18–35] expecting to see them no more.

The following parallels between this epistle and the Milesian charge may be traced:

- Acts 20:19 = Eph. 4:2. The phrase "lowliness of mind".

- Acts 20:27 = Eph. 1:11. The word "counsel", denoting the divine plan.

- Acts 20:32 = Eph. 3:20. The divine ability.

- Acts 20:32 = Eph. 2:20. The building upon the foundation.

- Acts 20:32 = Eph. 1:14,18 "The inheritance of the saints."

Purpose

The purpose of the Epistle, and to whom it was written, are matters of much speculation.[10]:p.229 and by C.H. Dodd as the "crown of Paulinism."[10]:p.229 In general, it is born out of its particular socio-historical context and the situational context of both the author and the audience. Originating in the circumstance of a multicultural church (primarily Jewish and Hellenistic), the author addressed issues appropriate to the diverse religious and cultural backgrounds present in the community.

For reasons that are unclear in the context and content of the letter itself, Paul exhorts the church repeatedly to embrace a specific view of salvation, which he then explicates. It seems most likely that Paul's Christology of sacrifice is the manner in which he intends to affect an environment of peace within the church. In short: "If Christ was sacrificed for your sake, be like him and be in submission to one another." Paul addresses hostility, division, and self-interest more than any other topic in the letter, leading many scholars to believe that his primary concern was not doctrinal, but behavioral.

Some theologians, such as Frank Charles Thompson,[11] agree the main theme of Ephesians is in response to the newly converted Jews who often separated themselves from their Gentile brethren. The unity of the church, especially between Jew and Gentile believers, is the keynote of the book. This is shown by the recurrence of such words and phrases as:

Together: made alive together;[Eph 2:5] raised up together, sitting together; 2:6 built together. 2:22

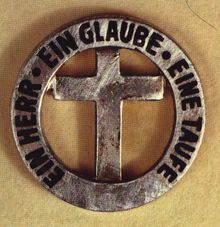

One, indicating unity: one new man,[Eph 2:15] one body,[2:16] one Spirit,[2:18] one hope,[4:4] one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all.[4:5-6]

The Pauline theme of unity based on a sacrificial Christology may also be noted in the epistle to the Philippians.

Interpretations

Ephesians is notable for its domestic code treatment in 5:22-6:4, covering husband-wife, parent-child, and master-slave relationships. In 5:22, wives are urged to submit to their husbands, and husbands to love their wives "as Christ loved the Church." Christian Egalitarian theologians, such as Katharine Bushnell and Jesse Pen-Lewis, interpret these commands in the context of the preceding verse, 5:21 for all Christians to "submit to one another." Thus, it is two-way, mutual submission of both husbands to wives and wives to husbands. This would be the only instance of this meaning of submission in the whole New Testament, indeed in any extent comparable Greek texts. The word simply does not connote mutuality.[12] Dallas Theological Seminary professor Daniel Wallace understands it to be an extension of 5:15-21 on being filled by the Holy Spirit.[7]

Ephesians 6:5 on master-slave relationships was one of the Bible verses used by Confederate slaveholders in support of a slaveholding position.[13]

See also

- Earlier Epistle to the Ephesians

- Textual variants in the Epistle to the Ephesians

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Ehrman, Bart D. (2004). The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. New York: Oxford. pp. 381–384. ISBN 0-19-515462-2.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "USCCB - NAB - Ephesians - Introduction". http://www.nccbuscc.org/nab/bible/ephesians/intro.htm. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 See Markus Barth, Ephesians: Introduction, Translation, and Commentary on Chapters 1–3 (New York: Doubleday and Company Inc., 1974), 50-51

- ↑ Perrin, Norman (1982). The New Testament: An Introduction. Second Edition.. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 218–222. ISBN 0155657267.

- ↑ Brown, Raymond E. The churches the apostles left behind Paulist Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0809126118.

- ↑ Perrin, Norman (1982). The New Testament: An Introduction. Second Edition.. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 218. ISBN 0155657267.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Wallace, Daniel B. "Ephesians:Introduction, Argument, and Outline." Web: [1] 1 Jan 2010

- ↑ These four views all come from Markus Barth, Ephesians: Introduction, Translation, and Commentary on Chapters 1-3 (New York: Doubleday and Company Inc., 1974), 38

- ↑ Höhner, Harold W. Ephesians: An Exegetical Commentary. Baker Academic, 2002. ISBN 978-0801026140

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bruce, F.F. The New International Commentary on the New Testament. Eerdmans, 1984, 1991. ISBN 0802824013.

- ↑ Thompson, Frank C. Thompson Chain Reference Study Bible (NIV). Kirkbride Bible Company, 2000. ISBN 978-0887070099

- ↑ O’Brien, Peter Thomas. The Letter to the Ephesians. The Pillar New Testament Commentary. Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1999.

- ↑ E.N. Elliott, ed. Cotton is king, and pro-slavery arguments comprising the writings of Hammond, Harper, Christy, Stringfellow, Hodge, Bledsoe, and Cartwright, on this important subject. Augusta, Ga. : Pritchard, Abbott & Loomis, 1860. Cotton is King - Google Books. http://books.google.com/books?id=ml8zC335PhEC. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

External links

- Ephesians Reading Room - extensive collection of online resources for Ephesians; Tyndale Seminary

- Ephesians Online - a collection of resources on the Epistle to the Ephesians

- Biblical Expository on Ephesians

This article incorporates text from Easton's Bible Dictionary (1897), a publication now in the public domain.

|

Epistle to the Ephesians

Pauline Prison Epistle

|

||

| Preceded by Galatians |

New Testament Books of the Bible |

Succeeded by Philippians |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||