Alsace

| Alsace | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| — Region of France — | |||

|

|||

|

|||

| Country | France | ||

| Prefecture | Strasbourg | ||

| Departments | |||

| Government | |||

| - President | Philippe Richert (2010-) (UMP) | ||

| Area | |||

| - Total | 8,280 km2 (3,196.9 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2006)[1] | |||

| - Total | 1,815,488 | ||

| - Density | 219.3/km2 (567.9/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| - Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| NUTS Region | FR4 | ||

| Website | region-alsace.eu | ||

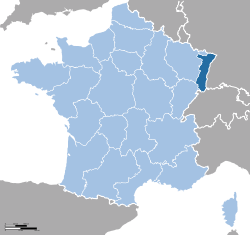

Alsace (French: Alsace [alzas]; Alsatian: Elsàss [ˈɛlzɔs]; German: Elsass, pre-1996: Elsaß, IPA: [ˈɛlzas]; Latin: Alsatia) is the fourth-smallest of the 26 regions of France in land area (8,280 km²), and the smallest in metropolitan France. It is also the sixth-most densely populated region in France and third most densely populated region in metropolitan France, with ca. 220 inhabitants per km² (total population in 2006: 1,815,488; January 1, 2008 estimate: 1,836,000). Alsace is located on France's eastern border and on the west bank of the upper Rhine adjacent to Germany and Switzerland. The political, economic and cultural capital as well as largest city of Alsace is Strasbourg. Due to that city being the seat of dozens of international organizations and bodies, Alsace is politically one of the most important regions in the European Union.

The name "Alsace" derives from the Germanic Ell-sass, meaning "Seated on the Ill",[2] a river in Alsace. The region was historically part of the Holy Roman Empire. It was gradually annexed by France in the 17th century under kings Louis XIII and Louis XIV and made one of the provinces of France. Alsace is frequently mentioned in conjunction with Lorraine, because German possession of parts of these two régions (as the imperial province Alsace-Lorraine, 1871–1918) was contested in the 19th and 20th centuries, during which Alsace changed hands four times between France and Germany in 75 years.

Although the historical language of Alsace is Alsatian, a Germanic language, today most Alsatians speak French, the official language of the country they have been a part of for most of the past three centuries. About 39% of the adult population, and probably less than 10% of the children, are fluent in Alsatian. There is therefore a substantial bilingual population in contemporary Alsace. [3] The place names used in this article are in French. See this list for the original German place names.

Contents |

History

Roman Alsace

In prehistoric times, Alsace was inhabited by nomadic hunters, but by 1500 BC, Celts began to settle in Alsace, clearing and cultivating the land. By 58 BC, the Romans had invaded and established Alsace as a center of viticulture. To protect this highly valued industry, the Romans built fortifications and military camps that evolved into various communities which have been inhabited continuously to the present day. While part of the Roman Empire, Alsace was part of Germania Superior.

Frankish Alsace

With the decline of the Roman Empire, Alsace became the territory of the Alemanni. The Alemanni were agricultural people, and their language formed the basis of the modern-day Alsatian dialect. Clovis and the Franks defeated the Alemanni during the 5th century, culminating with the Battle of Tolbiac, and Alsace became part of the Kingdom of Austrasia. Under Clovis' Merovingian successors the inhabitants were Christianized. Alsace remained under Frankish control until the Frankish realm, following the Oaths of Strasbourg of 842, was formally dissolved in 843 at the Treaty of Verdun; the grandsons of Charlemagne divided the realm into three parts. Alsace formed part of the Middle Francia, which was ruled by the youngest grandson Lothar I. Lothar died early in 855 and his realm was divided into three parts. The part known as Lotharingia, or Lorraine, was given to Lothar's son. The rest was shared between Lothar's brothers Charles the Bald (ruler of the West Frankish realm) and Louis the German (ruler of the East Frankish realm). The Kingdom of Lotharingia was short-lived, however; the region that was to become Alsace fell to the Holy Roman Empire as part of the Duchy of Swabia in the Treaty of Meersen in 870.

Alsace within the Holy Roman Empire

At about this time the entire region began to fragment into a number of feudal secular and ecclesiastical lordships, a situation which lasted into the 17th century and was a common process in Europe. Alsace experienced great prosperity during the 12th and 13th centuries under Hohenstaufen emperors. Frederick I set up Alsace as a province (a procuratio, not a provincia) to be ruled by ministeriales, a non-noble class of civil servants. The idea was that such men would be more tractable and less likely to alienate the fief from the crown out of their own greed. The province had a single provincial court (Landgericht) and a central administration with its seat at Hagenau. Frederick II designated the Bishop of Strasbourg to administer Alsace, but the authority of the bishop was challenged by Count Rudolph of Habsburg, who received his rights from Frederick II's son Conrad IV. Strasbourg began to grow to become the most populous and commercially-important town in the region. In 1262, after a long struggle with the ruling bishops, its citizens gained the status of free imperial city. A stop on the Paris-Vienna-Orient trade route, as well as a port on the Rhine route linking southern Germany and Switzerland to the Netherlands, England and Scandinavia, it became the political and economic center of the region. Cities such as Colmar and Hagenau also began to grow in economic importance and gained a kind of autonomy within the "Decapole" or "Dekapolis", a federation of ten free towns.

The prosperity of Alsace was terminated in the 14th century by a series of harsh winters, bad harvests, and the Black Death. These hardships were blamed on Jews, leading to the pogroms of 1336 and 1339. An additional natural disaster was the Rhine rift earthquake of 1356, one of Europe's worst which made ruins of Basel. Prosperity returned to Alsace under Habsburg administration during the Renaissance.

German central power had begun to decline following years of imperial adventures in Italian lands, ceding hegemony in Europe to France, which had long since centralized power. France began an aggressive policy of expanding eastward, first to the Rhône and Meuse Rivers, and when those borders were reached, aiming for the Rhine. In 1299, the French proposed a marriage alliance between Philip IV of France's sister and Albert I of Germany's son, with Alsace to be the dowry; however, the deal never came off. In 1307, the town of Belfort was first chartered by the Counts of Montbéliard. During the next century, France was to be militarily shattered by the Hundred Years' War, which prevented for a time any further tendencies in this direction. After the conclusion of the war, France was again free to pursue its desire to reach the Rhine and in 1444 a French army appeared in Lorraine and Alsace. It took up winter quarters, demanded the submission of Metz and Strasbourg and launched an attack on Basel.

In 1469, following the Treaty of St. Omer, Upper Alsace was sold by Archduke Sigismund of Austria to Charles of Burgundy. Although Charles was the nominal landlord, taxes were paid to Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor. The latter was able to use this tax and a dynastic marriage to his advantage to gain back full control of Upper Alsace (apart from the free towns, but including Belfort) in 1477 when it became part of the demesne of the Habsburg family, who were also rulers of the empire. The town of Mulhouse joined the Swiss Confederation in 1515, where it was to remain until 1798.

By the time of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, Strasbourg was a prosperous community, and its inhabitants accepted Protestantism in 1523. Martin Bucer was a prominent Protestant reformer in the region. His efforts were countered by the Roman Catholic Habsburgs who tried to eradicate heresy in Upper Alsace. As a result, Alsace was transformed into a mosaic of Catholic and Protestant territories. On the other hand, Mömpelgard (Montbéliard) to the southwest of Alsace, belonging to the Counts of Württemberg since 1397, remained a Protestant enclave in France until 1793.

Incorporation into France

This situation prevailed until 1639 when most of Alsace was conquered by France to prevent it falling into the hands of the Spanish Habsburgs, who wanted a clear road to their valuable and rebellious possessions in the Spanish Netherlands. This occurred in the greater context of the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648). Beset by enemies and to gain a free hand in Hungary, the Habsburgs sold their Sundgau territory (mostly in Upper Alsace) to France in 1646, which had occupied it, for the sum of 1.2 million Thalers. Thus, when the hostilities finally ceased in 1648 with the Treaty of Westphalia, most of Alsace went to France with some towns remaining independent. The treaty stipulations regarding Alsace were Byzantine and confusing; it is thought that this was purposely so that neither the French king nor the German emperor could gain tight control, but that one would play off the other, thereby assuring Alsace some measure of autonomy. Supporters of this theory point out that the treaty stipulations were authored by Imperial plenipotentiary Isaac Volmar, the former Chancellor of Alsace. The transfer of most of Alsace to France at the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 marked its start, along with Lorraine, as a contested territory between France and Germany (French-German enmity).

Because warfare had caused large numbers of the population (mainly in the countryside) to die or to flee, numerous immigrants arrived from Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Lorraine, Savoy and other areas after 1648 and until the mid-18th century. Between 1671-1711 Anabaptist refugees came from Switzerland, notably from Bern. Strasbourg became a main centre of the early Anabaptist movement.

France consolidated her hold with the 1679 Treaties of Nijmegen, which brought the towns under her control. France occupied Strasbourg in 1681 in an unprovoked action, and from 1688 onwards devastated large parts of southern Germany according to the Brûlez le Palatinat! policy. These territorial changes were reinforced at the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick which ended the War of the Grand Alliance. However, Alsace had a somewhat exceptional position in the Kingdom of France. The German language was still used in local government, school, and education and the German (Lutheran) University of Strasbourg was continued and attended by students from Germany. The Edict of Fontainebleau, which legalized the suppression of French Protestantism, was not applied in Alsace. In contrast to the rest of France, there was a relative religious tolerance, although the French authorities tried to promote Catholicism and the Lutheran Strasbourg Cathedral had to be handed over to the Catholics in 1681. There was a customs boundary along the Vosges mountains against the rest of France while there was no such boundary against Germany. For these reasons Alsace remained marked by German culture and economically oriented towards Germany until the French Revolution.

French Revolution

The year 1789 brought the French Revolution and with it the first division of Alsace into the départements of Haut- and Bas-Rhin. Alsatians played an active role in the French Revolution. On July 21, 1789, after receiving news of the Storming of the Bastille in Paris, a crowd of people stormed the Strasbourg city hall, forcing the city administrators to flee and putting symbolically an end to the feudal system in Alsace. In 1792, Rouget de Lisle composed in Strasbourg the Revolutionary marching song La Marseillaise, which later became the anthem of France. La Marseillaise was played for the first time in April of that year in front of the mayor of Strasbourg Philippe-Frédéric de Dietrich. Some of the most famous generals of the French Revolution also came from Alsace, notably Kellermann, the victor of Valmy, and Kléber, who led the armies of the French Republic in Vendée.

At the same time, some Alsatians were in opposition to the Jacobins and sympathetic to the invading forces of Austria and Prussia who sought to crush the nascent revolutionary republic. Many of the residents of the Sundgau made "pilgrimages" to places like Mariastein Abbey, near Basel, in Switzerland, for baptisms and weddings. When the French Revolutionary Army of the Rhine was victorious, tens of thousands fled east before it. When they were later permitted to return (in some cases not until 1799), it was often to find that their lands and homes had been confiscated. These conditions led to emigration by hundreds of families to newly-vacant lands in the Russian Empire in 1803–4 and again in 1808. A poignant retelling of this event based on what Goethe had personally witnessed can be found in his long poem Hermann and Dorothea.

In response to the restoration of Napoleon I of France, in 1814 and 1815, Alsace was occupied by foreign forces, including over 280,000 soldiers and 90,000 horses in Bas-Rhin alone. This had grave effects on trade and the economy of the region since former overland trade routes were switched to newly-opened Mediterranean and Atlantic seaports.

The population grew rapidly, from 800,000 in 1814 to 914,000 in 1830 and 1,067,000 in 1846. The combination of factors meant hunger, housing shortages and a lack of work for young people. Thus, it is not surprising that people left Alsace, not only to Paris, where the Alsatian community grew in numbers, with famous members such as Baron Haussmann, but also to far away places like Russia and the Austrian Empire to take advantage of new opportunities offered there. Austria had conquered lands in Eastern Europe from the Ottoman Empire and offered generous terms for colonists in order to consolidate their hold on the lands. Many Alsatians also began to sail for the United States, where after 1867 slave importation had been banned and new workers were needed for the cotton fields.

Between France and Germany

France was brought by the Ems Dispatch into the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), and was defeated by the Kingdom of Prussia and other German states. The end of the war led to the unification of Germany. Otto von Bismarck annexed Alsace and northern Lorraine to the new German Empire in 1871;[4] unlike other members states of the German federation, which had governments of their own, the new Imperial territory of Alsace-Lorraine was under the sole authority of the Kaiser, administered directly by the imperial government in Berlin. Between 100,000 to 130,000 Alsatians (of a total population of about a million and a half) chose to remain French citizens and leave Reichsland Elsaß-Lothringen, many of them resettling in French Algeria as Pied-Noirs. Only in 1911 was Alsace-Lorraine granted some measure of autonomy, which was manifested also in a flag and an anthem (Elsässisches Fahnenlied). In 1913, however, the Saverne Affair showed the limits of this new tolerance of the Alsatian identity.

During World War I, to avoid ground fights between brothers, many Alsatians served as sailors in the Kaiserliche Marine and took part in the Naval mutinies that led to the abdication of the Kaiser in November 1918, which left Alsace-Lorraine without a nominal head of state. The sailors returned home and tried to found a republic. While Jacques Peirotes, at this time deputy at the Landrat Elsass-Lothringen and just elected mayor of Strasbourg, proclaimed the forfeiture of the German Empire and the advent of the French Republic, a self-proclaimed government of Alsace-Lorraine declared independence as the "Republic of Alsace-Lorraine". French troops entered Alsace less than two weeks later to quash the worker strikes and remove the newly established soviets and revolutionaries from power. At the arrival of the French soldiers many Alsatians and even, ironically, local Prussian/German administrators & bureaucrats cheered due to the re-establishment of order (which can be seen and is described in detail in the reference video below)[5] Although U.S. President Woodrow Wilson had insisted that the région was self-ruling by legal status, as its constitution had stated it was bound to the sole authority of the Kaiser and not to the German state, France tolerated no plebiscite, as granted by the League of Nations to some eastern German territories at this time, because Alsatians were considered by the French public as fellow Frenchmen liberated from German rule. Germany ceded the region to France under the Treaty of Versailles.

After World War I, the establishment of German identity in Alsace was reversed, as all Germans who had settled in Alsace since 1871 were expelled. Policies forbidding the use of German and requiring that of French were introduced.[6] However, in order not to antagonize the Alsatians, the region was not subjected to some legal changes that had occurred in the rest of France between 1871 and 1919, such as the 1905 French Law of Separation of Church and State.

The région was effectively annexed by Germany in 1940 during World War II, and incorporated into the Greater German Reich, which had been restructured into Reichsgaue. Alsace was merged with Baden, and Lorraine with the Saarland, to become part of a planned Westmark. The annexation, while putting a halt to the anti-German discrimination in the région, subjected it to the cruel Nazi dictatorship, which was loathed by most of the people. The German government never negotiated or declared a formal annexation, however, in order to preserve the possibility of an agreement with the West.

France regained control of the war-torn area in late 1944 and resumed its policy of promoting the French language and repressing the German with uncompromising vigor. For instance, from 1945 to 1984, the use of German in newspapers was restricted to a maximum of 25%.

However, today the territory enjoys laws in certain areas that are significantly different from the rest of France - this is known as the local law.

In more recent years, Alsatian is again being promoted by local, national and European authorities as an element of the region's identity. Alsatian is taught in schools (but not mandatory) as one of the regional languages of France. German is also taught as a foreign language in local kindergartens and schools. However, the Constitution of France still requires that French be the only official language of the Republic.

Timeline

| Year(s) | Event | Ruled by | Official language |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5400–4500 BC | Bandkeramiker/Linear Pottery cultures | — | None |

| 2300–750 BC | Bell Beaker cultures | — | None; Proto-Celtic spoken |

| 750–450 BC | Halstatt early Iron Age culture (early Celts) | — | None; Old Celtic spoken |

| 450–58 BC | Celts/Gauls firmly secured in entire Gaul, Alsace; trade with Greece is evident (Vix) | Celts/Gauls | None; Gaulish variety of Celtic widely spoken |

| 58 / 44 BC–AD 260 | Alsace and Gaul conquered by Caesar, provinciated to Germania Superior | Roman Empire | Latin; Gallic widely spoken |

| 260–274 | Postumus founds breakaway Gallic Empire | Gallic Empire | Latin, Gallic |

| 274–286 | Rome reconquers the Gallic Empire, Alsace | Roman Empire | Latin, Germanic (only in Argentoratum) |

| 286–378 | Diocletian divides the Roman Empire into Western and Eastern sectors | Roman Empire | |

| around 300 | Beginning of Germanic migrations to the Roman Empire | Roman Empire | |

| 378–395 | The Visigoths rebel, precursor to waves of German, and Hun invasions | Roman Empire | |

| 395–436 | Death of Theodosius I, causing a permanent division between Western and Eastern Rome | Western Roman Empire | |

| 436–486 | Germanic invasions of the Western Roman Empire | Roman Tributary of Gaul | |

| 486–511 | Lower Alsace conquered by the Franks | Frankish Realm | Old Frankish, Latin |

| 531–614 | Upper Alsace conquered by the Franks | Frankish Realm | |

| 614–795 | Totality of Alsace to the Frankish Kingdom | Frankish Realm | |

| 795–814 | Charlemagne begins reign, Charlemagne crowned Emperor of the Romans on December 25, 800 | Frankish Empire | Old Frankish |

| 814 | Death of Charlemagne | Carolingian Empire | Old Frankish, Old High German |

| 847–870 | Treaty of Verdun gives Alsace and Lotharingia to Lothar I | Middle Francia (Carolingian Empire) | Frankish, Old High German |

| 870–889 | Treaty of Mersen gives Alsace to East Francia | East Francia (German Kingdom of the Carolingian Empire) | Frankish, Old High German |

| 889–962 | Carolingian Empire breaks up into five Kingdoms, Magyars and Vikings periodically raid Alsace | Kingdom of Germany | Old High German, Frankish |

| 962–1618 | Otto I crowned Holy Roman Emperor | Holy Roman Empire | Old High German, Modern High German. (Alemannic spoken widely) |

| 1618–1674 | Louis XIII annexes portions of Alsace during the Thirty Years' War | Holy Roman Empire | German |

| 1674–1871 | Louis XIV annexes the rest of Alsace during the Franco-Dutch War, establishing full French sovereignty over the region | Kingdom of France | Official :French Alsatian and German tolerated, but strongly suppressed in official circles. |

| 1871–1918 | Franco-Prussian war causes French cession of Alsace to German Empire | German Empire | German |

| 1919–1940 | Treaty of Versailles causes German cession of Alsace to France | France | French |

| 1940–1944 | Nazi Germany conquers Alsace | Nazi Germany | German |

| 1945–present | French control | France | Official: French. Alsatian and German strongly suppressed until 1972. |

Tourism

Having been early and always densely populated, Alsace is famous for its high number of picturesque villages, churches and castles and for the various beauties of its three main towns, in spite of severe destructions suffered throughout five centuries of wars between France and Germany.

Alsace is furthermore famous for its vineyards (especially along the 170 km of the Route des Vins d'Alsace from Marlenheim to Thann) and the Vosges mountains with their thick and green forests and picturesque lakes.

from the Maginot Line

- Old towns of Strasbourg, Colmar, Sélestat, Guebwiller, Saverne, Obernai

- Smaller cities and villages : Molsheim, Rosheim, Riquewihr, Ribeauvillé, Kaysersberg, Wissembourg, Neuwiller-lès-Saverne, Marmoutier, Rouffach, Soultz-Haut-Rhin, Bergheim, Hunspach, Seebach, Turckheim, Eguisheim, Neuf-Brisach, Ferrette, Niedermorschwihr

- Churches (as main sights in otherwise less remarkable places) : Thann, Andlau, Murbach, Ebersmunster, Niederhaslach, Sigolsheim, Lautenbach, Epfig, Altorf, Ottmarsheim, Domfessel, Niederhaslach, Marmoutier and the fortified church at Hunawihr

- Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg

- Other castles : Ortenbourg and Ramstein (above Sélestat), Hohlandsbourg, Fleckenstein, Haut-Barr (above Saverne), Saint-Ulrich (above Ribeauvillé), Lichtenberg, Wangenbourg, the three Castles of Eguisheim, Pflixbourg, Wasigenstein, Andlau, Grand Geroldseck, Wasenbourg

- Musée de l'automobile de Mulhouse

- Cité du train museum in Mulhouse

- The EDF museum in Mulhouse

- Ungersheim's "écomusée" (open air museum) and "Bioscope" (leisure park about environment)

- Musée historique in Haguenau, largest museum in Bas-Rhin outside of Strasbourg

- Bibliothèque humaniste in Sélestat, one of the oldest public libraries in the world

- Christmas markets in Kaysersberg, Strasbourg, Mulhouse and Colmar

- Departmental Centre of the History of Families (CDHF) in Guebwiller

- The Maginot Line: Ouvrage Schoenenbourg

- Mount Ste Odile

- Route des Vins d'Alsace (Alsace Wine Route)

- Mémorial d'Alsace-Lorraine in Schirmeck

- The Struthof, the only concentration and extermination camp on the French territory during WWII

- Famous mountains: Massif du Donon, Grand Ballon, Petit Ballon, Ballon d'Alsace, Hohneck, Hartmannswillerkopf

- National park : Parc naturel des Vosges du Nord

- Regional park : Parc naturel régional des Ballons des Vosges (south of the Vosges)

Climate

Alsace has a semi-continental climate with cold and dry winters and hot summers. There is little precipitation because the Vosges protect it from the west. The city of Colmar has a sunny microclimate; it is the second driest city in France, with an annual precipitation of just 550 mm, making it ideal for vin d'Alsace (Alsatian wine).

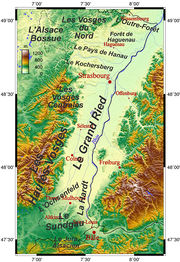

Topography

Alsace has an area of 8,283 km², making it the smallest région of metropolitan France. It is almost four times longer than it is wide, corresponding to a plain between the Rhine in the east and the Vosges mountains in the west.

It includes the départements of Haut-Rhin and Bas-Rhin (known previously as Sundgau and Nordgau). It borders Germany on the north and the east, Switzerland and Franche-Comté on the south, and Lorraine on the west.

Several valleys are also found in the région. Its highest point is the Grand Ballon in Haut-Rhin, which reaches a height of 1426 m.

Geology

Alsace is the part of the plain of the Rhine located at the west of the Rhine, on its left bank. It is a rift or graben, from the Oligocene epoch, associated with its horsts : the Vosges and the Black Forest.

The Jura Mountains, formed by slip (induced by the alpine uplift) of the Mesozoic cover on the Triassic formations, goes through the area of Belfort.

Flora

It contains many forests, primarily in the Vosges and in Bas-Rhin (Haguenau Forest).

Politics

Alsace is one of the most conservative régions of France. It is one of just two régions in metropolitan France where the conservative right won the 2004 région elections and thus controls the Alsace Regional Council. Conservative leader Nicolas Sarkozy got his best score in Alsace (over 65%) in the second round of the French presidential elections of 2007. The president of the Regional Council is Adrien Zeller, a member of the Union for a Popular Movement. The frequently changing status of the région throughout history has left its mark on modern day politics in terms of a particular interest in national identity issues. Alsace is also one of the most pro-EU regions of France. It was one of the few French regions that voted 'yes' to the European Constitution in 2005.

Administrative divisions

The Alsace region is divided into 2 departments, 13 departmental arrondissements, 75 cantons (not shown here), and 904 communes:

Department of Bas-Rhin

(Number of communes in parentheses)

- Arrondissement of Haguenau (56)

- Arrondissement of Molsheim (69)

- Arrondissement of Saverne (128)

- Arrondissement of Sélestat-Erstein (101)

- Arrondissement of Strasbourg-Campagne (104)[7]

- Arrondissement of Strasbourg-Ville (1)

- Arrondissement of Wissembourg (68)

Department of Haut-Rhin

(Number of communes in parentheses)

- Arrondissement of Altkirch (111)

- Arrondissement of Colmar (62)

- Arrondissement of Guebwiller (47)

- Arrondissement of Mulhouse (73)

- Arrondissement of Ribeauvillé (32)

- Arrondissement of Thann (52)

Economy

According to the Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques (INSEE), Alsace had a gross domestic product of 44.3 billion euros in 2002. With a GDP per capita of €24,804, it was the second-place région of France, losing only to Île-de-France. 68% of its jobs are in the services; 25% are in industry, making Alsace one of France's most industrialised régions.

Alsace is a région of varied economic activity, including:

- viticulture (mostly along the Route des Vins d'Alsace between Marlenheim and Thann);

- hop harvesting and brewing (half of French beer is produced in Alsace, especially in the vicinity of Strasbourg, notably in Strasbourg-Cronenbourg, Schiltigheim and Obernai);

- forestry development

- automobile industry (Mulhouse)

- life sciences, as part of the trinational BioValley and

- tourism

- potassium chloride (until the late 20th century) and phosphate mining

Alsace has many international ties and 35% of firms are foreign companies (notably German, Swiss, American, Japanese, and Scandinavian).

Demographics

Alsace's population increased to 1,836,000 in 2008. It has regularly increased over time, except in wartime, by both natural growth and migration. This growth has even accelerated at the end of the 20th century. INSEE estimates that its population will grow 12.9% to 19.5% between 1999 and 2030.

With a density of 222/km², Alsace is the third most densely populated région in metropolitan France.

Transportation

Roads

Most major car journeys are made on the A35 autoroute (with intermittent areas of dual carriageways), which links Saint-Louis on the Swiss border to Lauterbourg on the German border.

The A4 toll road (towards Paris) begins 20 km northwest of Strasbourg and the A36 toll road towards Lyon, begins 10 km west from Mulhouse.

Spaghetti-junctions (built in the 1970s and 1980s) are prominent in the comprehensive system of motorways in Alsace, especially in the outlying areas of Strasbourg and Mulhouse. These cause a major buildup of traffic and are the main sources of pollution in the towns, notably in Strasbourg where the motorway traffic of the A35 was 170,000 per day in 2002.

At present, plans are being considered for building a new dual carriageway west of Strasbourg, which would reduce the buildup of traffic in that area by picking up north- and southbound vehicles and getting rid of the buildup outside of Strasbourg. The line plans to link up the interchange of Hœrdt to the north of Strasbourg, with Innenheim in the southwest. The opening is envisaged at the end of 2011, with an average usage of 41,000 vehicles a day. Estimates of the French Works Commissioner however, raised some doubts over the interest of such a project, since it would pick up only about 10% of the traffic of the A35 at Strasbourg.

To add to the buildup of traffic, the neighbouring German state of Baden-Württemberg has imposed a tax on heavy-goods vehicles using their Autobahnen. Thus, a part of the HGVs travelling from north Germany to Switzerland or southern Alsace bypasses the A5 on the Alsace-Baden-Württemberg border and uses the untolled, French A35 instead.

The french Assemblée Nationale allowed a tax on HGVs using the alsatian road network in 2005. It must be applicated since beginning 2008.

Trains

TER Alsace is the rail network serving Alsace. Its network is articulated around the city of Strasbourg. It's one of the most developed rail network in France, financially sustained partly by the French railroad SNCF, and partly by the région Alsace.

Because the Vosges are surmountable only by the Col de Saverne and the Belfort Gap, it has been suggested that Alsace needs to open up and get closer to France in terms of its rail links.

The TGV Est (Paris - Strasbourg) was brought into service in June 2007, and different plans are due to be implemented:

- the TGV Rhin-Rhône or a Dijon-Mulhouse line (to start in construction in 2006, with anticipated completion in 2011);

- an interconnection with the German InterCityExpress, as far as Kehl and/or Ottmarsheim;

- a tram-train system in Mulhouse (May 2006), then Strasbourg (2011).

However, the abandoned Maurice-Lemaire tunnel towards Saint-Dié-des-Vosges was rebuilt as a toll road.

Rivers

Port traffic of Alsace exceeds 15 million tonnes, of which about three quarters is centred on Strasbourg, which is the second busiest French fluvial harbour. The enlargement plan of the Rhine-Rhône channel, intended to link up the Mediterranean Sea and Central Europe (Rhine, Danube, North Sea and Baltic Sea) was abandoned in 1998 for reasons of expense and land erosion, notably in the Doubs valley.

Air traffic

There are two international airports in Alsace:

- the international airport of Strasbourg in Entzheim;

- the international EuroAirport Basel-Mulhouse-Freiburg, which is the seventh largest French airport in terms of traffic.

Strasbourg is also two hours away from one of the largest European airports, Frankfurt Main.

Religion

Most of the Alsatian population is Roman Catholic, but largely because of the region's German heritage, a significant Protestant community also exists: today, the EPAL (a united Lutheran-Reformed church) is France's second largest Protestant church. Unlike the rest of France, the Alsace-Moselle territory still adheres to the Napoleonic Concordat of 1801, which provides public subsidies to the Roman Catholic, Lutheran, and Calvinist churches, as well as to Jewish synagogues; public education in these faiths is offered. This divergence in policy from the French majority is due to the region having been part of Imperial Germany when the 1905 law separating the French church and state was instituted (for a more comprehensive history, see: Alsace-Lorraine). Controversy erupts periodically on the appropriateness of this legal disposition, as well does the exclusion of other religions from this arrangement.

Following the Protestant Reformation, promoted by local reformer Martin Bucer, the principle of cuius regio, eius religio led to a certain amount of religious diversity in the highlands of northern Alsace. Landowners, who as "local lords" had the right to decide which religion was allowed on their land, were eager to entice populations from the more attractive lowlands to settle and develop their property. Many accepted without discrimination Catholics, Lutherans, Calvinists, Jews and Anabaptists. Multiconfessional villages appeared, particularly in the region of Alsace bossue. Alsace became one of the French regions boasting a thriving Jewish community, and the only region with a noticeable Anabaptist population. The schism of the Amish under the lead of Jacob Amman from the Mennonites occurred in 1693 in Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines. The strongly Catholic Louis XIV tried in vain to drive them from Alsace. When Napoleon imposed military conscription without religious exception, most emigrated to the American continent.

In 1707, the simultaneum was established, by which many Reformed and Lutheran church buildings were forced to allow Catholic services. About 50 such "simultaneous churches" still exist in modern Alsace, though they tend to hold Catholic services only occasionally.

Culture

Alsace historically was part of the Holy Roman Empire and the German realm of culture. Since the 17th century, the region has passed between German and French control numerous times, resulting in a cultural blend. Germanic traits remain in the more traditional, rural parts of the culture, such as the cuisine and architecture, whereas modern institutions are totally dominated by French culture.

Language

Although German dialects were spoken in Alsace for most of its history, the dominant language in Alsace today is French.

The traditional language of the région is Alsatian, an Alemannic dialect of Upper German and thus closely related to Swiss German. Some Frankish dialects of West Central German are also spoken in the extreme north of Alsace. Neither Alsatian nor the Frankish dialects have any form of official status, as is customary for regional languages in France, although both are now recognized as languages of France and can be chosen as subjects in lycées.

Although Alsace has been annexed by France several times in the past, the region had no direct connection with the French State for several centuries. From the end of the Roman Empire (5th century) to the French annexation (17th century), Alsace was politically part of the Germanic world.

The towns of Alsace were the first to adopt German language as their official language, instead of Latin, during the Lutheran Reform. It was in Strasbourg that German was first used for the Liturgy. It was also in Strasbourg that the first German Bible was published in 1466.

From the annexation of Alsace by France in the 17th century and the language policy of the French Revolution up to 1870, knowledge of French in Alsace increased considerably. With the education reforms of the 19th century, the middle classes began to speak and write French well. The French language never really managed, however, to win over the masses, the vast majority of whom continued to speak their German dialects and write in German (which we would now call "standard German").

Between 1870 and 1918, Alsace was annexed by the German Empire in the form of an imperial province or Reichsland, and the official language, especially in schools, once again became (standard) German; French lost ground to such an extent that it has been estimated that only 2% of the population spoke French fluently and only 8% had some knowledge of it (Maugue, 1970).

After 1918, French was the only language used in schools, and particularly primary schools. After much argument and discussion and after many temporary measures, a memorandum was issued by Vice-Chancellor Pfister in 1927 and governed education in primary schools until 1939.

After annexation by the Nazis (1940-1945), during which the only language used in education was standard German, and following the Second World War, the 1927 regulation was not reinstated and the teaching of German in primary schools was suspended by a provisional rectorial decree, which was supposed to enable French to regain lost ground. The teaching of German became a major issue, however, as early as 1946. Following World War II, the French government pursued, in line with its traditional language policy, a campaign to suppress the use of German as part of a wider a Francization campaign.

In 1951, Article 10 of the Deixonne law on the teaching of local languages and dialects made provision for Breton, Basque, Catalan and old Provençal, but not for Corsican, Dutch (West Flemish) or German in Alsace and Moselle.

It was not until a Decree of 18 December 1952, supplemented by an Order of 19 December of the same year, that optional teaching of the German language was introduced in elementary schools in Communes where the language of habitual use was the Alsatian dialect. Because of many objections by teachers and much official and unofficial pressure, this Decree was not very rigorously enforced.

In 1972, the Inspector General of German, Georges Holderith, obtained authorization to reintroduce German into 33 intermediate classes, on an experimental basis. This teaching of German, referred to as the Holderith Reform, was later extended to all pupils in the last two years of elementary school. This reform is still largely the basis of German teaching in elementary schools today.

It was not until 9 June 1982, with the Circulaire sur la langue et la culture régionales en Alsace (Memorandum on regional language and culture in Alsace) issued by the Vice-Chancellor of the Académie Pierre Deyon, that the teaching of German in primary schools in Alsace really began to be given more official status. The Ministerial Memorandum of 21 June 1982, known as the Circulaire Savary, introduced financial support, over three years, for the teaching of regional languages in schools and universities. This memorandum was, however, implemented in a fairly lax manner.

More recently, in 1987, Article III of a national Minute concerning the early teaching of German in France contained special instructions for the teaching of German in Alsace and Moselle.[8]

Both Alsatian and Standard German were for a time banned from public life (including street and city names, official administration, and educational system). Though the ban has been lifted, Alsace-Lorraine is today very French in language and culture. Few young people speak Alsatian today, though the closely-related Alemannic German survives on the opposite bank of the Rhine, in Baden, and especially in Switzerland. However, while French is the major language of the region, the Alsatian dialect of French is heavily influenced by German, in phonology and vocabulary.

Often assumed to be a bilingual region, Alsace has in fact moved toward a situation of total French monolingualism. This is documented in Le declin du dialecte alsacien, a study funded by the General Council of Alsace and carried out in twenty secondary schools by Calvin Veltman and M.N. Denis. This situation has spurred a movement to preserve the Alsatian language, which is perceived as endangered, a situation paralleled in other régions of France, such as Brittany or Occitania. Alsatian is now taught in French high schools, but the overwhelming presence of French media make the survival of Alsatian uncertain among younger generations. Increasingly, French is the only language used at home and at work, whereas a growing number of people have a good knowledge of standard German as a foreign language learned in school.

The constitution of the Fifth Republic states that French alone is the official language of the Republic. However Alsatian, along with other regional languages, are recognized by the French government in the official list of languages of France. A 1999 INSEE survey counted 548,000 adult speakers of Alsatian in France, making it the second most-spoken regional language in the country (after Occitan). Like all regional languages in France, however, the transmission of Alsatian is on the decline. While 39% of the adult population of Alsace speaks Alsatian, only one in four children speaks it, and only one in ten children uses it regularly.

In 1992 the French Government signed the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, which however is not ratified yet (2009) by the French Parliament and therefore not in force.

Cuisine

Alsatian cuisine, strongly based on Germanic culinary traditions, is marked by the use of pork in various forms. Traditional dishes include baeckeoffe, flammekueche (in French: tarte flambée), choucroute, and fleischnacka. Southern Alsace, also called the Sundgau, is characterized by carpe frite.

The festivities of the year's end involve the production of a great variety of biscuits and small cakes called bredala as well as pain d'épices (gingerbread), especially from Gertwiller, which are given to children starting on Saint Nicholas Day.

Alsace is an important wine-producing région. Vins d'Alsace (Alsatian wines) are mostly white and display a strong Germanic influence. Alsace produces some of the world's most noted dry rieslings and is the only région in France to produce mostly varietal wines identified by the names of the grapes used (wine from Burgundy is also mainly varietal, but not normally identified as such), typically from grapes also used in Germany. The most notable example is gewurztraminer.

Alsace is also the main beer-producing région of France, thanks primarily to breweries in and near Strasbourg. These include those of Fischer, Karlsbräu, Kronenbourg, and Heineken International. Hops are grown in Kochersberg and in northern Alsace. Schnapps is also traditionally made in Alsace, but it is in decline because home distillers are becoming less common and the consumption of traditional, strong, alcoholic beverages is decreasing.

Alsatian food is synonymous with conviviality, the dishes are substantial and served in generous portions and it has one of the richest regional kitchens.

The gastronomic symbol of the région is undoubtedly Sauerkraut. The word Sauerkraut in Alsatian has the form sûrkrût, same as in other southwestern German dialects, and means "sour cabbage" as its Standard German equivalent. This word was included into the French language as choucroute. To make it, the cabbage is finely shredded, layered with salt and juniper and left to ferment in wooden barrels. Sauerkraut can be served with poultry, pork, sausage or even fish. Traditionally it is served with pork, Strasbourg sausage or frankfurters, bacon, smoked pork or smoked Morteau or Montbéliard sausages or a selection of pork products. Served alongside are often roasted or steamed potatoes or dumplings.

Alsace is also well known for its foie gras made in the region since the 17th century. Additionally, Alsace is known for its fruit juices, mineral waters and wines.

Architecture

The traditional habitat of the Alsatian lowland, like in other regions of Germany and Northern Europe, consists of houses constructed with walls in timber framing and cob and roofing in flat tiles. This type of construction is abundant in adjacent parts of Germany and can be seen in other areas of France, but their particular abundance in Alsace is owed to several reasons:

- The proximity to the Vosges where the wood can be found.

- During periods of war and bubonic plague, villages were often burned down, so to prevent the collapse of the upper floors, ground floors were built of stone and upper floors built in half-timberings to prevent the spread of fire.

- During most of the part of its history, a great part of Alsace was flooded by the Rhine every year. Half-timbered houses were easy to knock down and to move around during those times (a day was necessary to move it and a day to rebuild it in another place).

However, half-timbering was found to increase the risk of fire, which is why from the 19th century, it began to be rendered. In recent times, villagers started to paint the rendering white in accordance with Beaux-Arts movements. To discourage this, the region's authorities gave financial grants to the inhabitants to paint the rendering in various colors, in order to return to the original style and many inhabitants accepted (more for financial reasons than by firm belief).

Symbolism

The stork is a main feature of Alsace and was the subject of many legends told to children. The bird practically disappeared around 1970, but re-population efforts are continuing. They are mostly found on roofs of houses, churches and other public buildings in Alsace.

Notable Alsatians

|

|

Major communities

German original names in brackets if French names are different

- Mulhouse (Mülhausen)

- Saint-Louis (St. Ludwig)

- Saverne (Zabern)

- Schiltigheim

- Sélestat (Schlettstadt)

- Strasbourg (Straßburg)

- Wittenheim

Sister provinces

There is an accord de coopération internationale between Alsace and the following regions:[9]

- Gyeongsangbuk-do, South Korea

- Lower Silesia, Poland

- Upper Austria, Austria

- Quebec, Canada

- Jiangsu, China

- Moscow, Russia

- Vest, Romania

See also

- German place names (Alsace)

- History of Jews in Alsace

- Musée alsacien (Strasbourg)

- Route Romane d'Alsace

Footnotes

- ↑ "Insee - Résultats du recensement de la population - 2006 - Alsace" (in (French)). Recensement.insee.fr. http://www.recensement.insee.fr/chiffresCles.action?zoneSearchField=ALSACE&codeZone=42-REG&idTheme=3. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ↑ Roland Kaltenbach : Le guide de l’Alsace, La Manufacture 1992, ISBN 2-7377-0308-5, page 36

- ↑ [1] "L'alsacien, deuxième langue régionale de France" Insee, Chiffres pour l'Alsace no. 12, December 2002

- ↑ In facts, France ceded more than nine tenth of Alsace and one fourth of Lorraine as stipulated in the treaty of Frankfurt. De jure, that wasn't an annexion any more.

- ↑ Have a look at this archive video.

- ↑ At the opposite, the legal propaganda for political elections was allowed to go with a German translation from 1919 to 2008.

- ↑ Note: the commune of Strasbourg is not inside the arrondissement of Strasbourg-Campagne but it is nonetheless the seat of the Strasbourg-Campagne sous-préfecture buildings and administration.

- ↑ "UOC - Universitat Oberta de Catalunya". Uoc.es. http://www.uoc.es/euromosaic/web/document/alemany/an/i3/i3.html. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ↑ Les Accords de coopération entre l’Alsace et... (French)

Bibliography

- Assall, Paul. Juden im Elsass. Zürich: Rio Verlag. ISBN 3-907668-00-6

- Das Elsass: Ein literarischer Reisebegleiter. Frankfurt a. M.: Insel Verlag, 2001. ISBN 3-4583-4446-2

- Erbe, Michael (Hrsg.) Das Elsass: Historische Landschaft im Wandel der Zeiten. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2002. ISBN 3-17-015771-X

- Faber, Gustav. Elsass. München: Artemis-Cicerone Kunst- und Reiseführer, 1989.

- Fischer, Christopher J. Alsace to the Alsatians? Visions and Divisions of Alsatian Regionalism, 1870-1939 (Berghahn Books, 2010); ; 235 pages;

- Gerson, Daniel. Die Kehrseite der Emanzipation in Frankreich: Judenfeindschaft im Elsass 1778 bis 1848. Essen: Klartext, 2006. ISBN 3-89861-408-5

- Haeberlin, Marc. Elsass, meine große Liebe. Orselina, La Tavola 2004. ISBN 3-9099-0908-6

− Rezension über das „Schlaraffenland“ Elsass - Herden, Ralf Bernd. Straßburg Belagerung 1870. Norderstedt: BoD, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8334-5147-8

- Mehling, Marianne (Hrsg.) Knaurs Kulturführer in Farbe Elsaß. München: Droemer Knaur, 1984.

- Putnam, Ruth. Alsace and Lorraine: From Cæsar to Kaiser, 58 B.C.-1871 A.D. New York: 1915.

- Schreiber, Hermann. Das Elsaß und seine Geschichte, eine Kulturlandschaft im Spannungsfeld zweier Völker. Augsburg: Weltbild, 1996.

- Schwengler, Bernard. Le Syndrome Alsacien: d'Letschte? Strasbourg: Éditions Oberlin, 1989. ISBN 2-85369-096-2

- Ungerer, Tomi. Elsass. Das offene Herz Europas. Straßburg: Édition La Nuée Bleue, 2004. ISBN 2-7165-0618-3

- Ungerer, Tomi, Danièle Brison, and Tony Schneider. Die elsässische Küche. 60 Rezepte aus der Weinstube L'Arsenal. Straßburg: Édition DNA, 1994. ISBN 2-7165-0341-9

- Vogler, Bernard and Hermann Lersch. Das Elsass. Morstadt: Éditions Ouest-France, 2000. ISBN 3-8857-1260-1

External links

- Tourism-Alsace.com Info from the Alsace Tourism Board

- Official website of the Alsace regional council

- Rhine Online - life in southern Alsace and neighbouring Basel and Baden Wuerrtemburg

- Alsace at the Open Directory Project

- Statistics and figures on Alsace on the website of the INSEE (French)

- Alsace.net: Directory of Alsatian Websites (French)

- Jews and Judaism in Alsace (French)

- "Museums of Alsace" (French)

- Churches and chapels of Alsace (pictures only) (French)

- Medieval castles of Alsace (pictures only) (French)

- "Alsatian language Wiki" (Elsassisch)

- "Synagogues d'Alsace" (French)

- "Origins of Alsace" (French)

- The Alsatian Library of Mutual Credit (French)

|

||||||||

|

|||||||