Egyptology

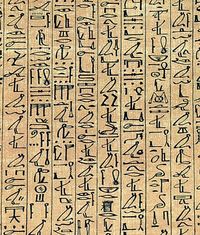

Egyptology (from Egypt and Greek -λογία, -logia. Arabic: علم المصريات) is a major field of archaeology, the study of ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end of its native religious practices in the AD 4th century. A practitioner of the discipline is an Egyptologist.

Contents |

Development of the field

The first Egyptologists

The first Egyptologists were the ancient Egyptians themselves. Thutmose IV restored the Sphinx and had the dream that inspired his restoration carved on the famous Dream Stele. Less than two centuries later, Prince Khaemweset, fourth son of Ramesses II, is famed for identifying and restoring historic buildings, tombs and temples including the pyramid.

Graeco-Roman Period

Some of the first historical accounts of Egypt were given by Herodotus, Strabo, Diodorus Siculus and the largely lost work of Manetho, an Egyptian priest, during the reign of Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II in the 3rd century BC.

Muslim Egyptologists

Progress was made by Muslim historians in Egypt and elsewhere from the 9th century AD. The first known attempts at deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs were made by Dhul-Nun al-Misri and Ibn Wahshiyya in the 9th century, who were able to at least partly understand what was written in the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, by relating them to the contemporary Coptic language used by Coptic priests in their time. Abdul Latif al-Baghdadi, a teacher at Cairo's Al-Azhar University in the 13th century, wrote detailed descriptions on ancient Egyptian monuments. Similarly, the 15th-century Egyptian historian al-Maqrizi wrote detailed accounts of Egyptian antiquities.

European explorers

European exploration and travel writings of ancient Egypt commenced from the 13th century onward, with only occasional detours into a more scientific approach, notably by John Greaves, Claude Sicard, Benoît de Maillet, Frederic Louis Norden and Richard Pococke. In the early 16th century, the Jesuit scientist-priest Athanasius Kircher was the first to identify the phonetic importance of Egyptian hieroglyphs, and he demonstrated Coptic as a vestige of early Egyptian, for which he is considered a "founder" of Egyptology.[1] In the late 18th century, with Napoleon's scholars' recording of Egyptian flora, fauna and history (published as Description de l'Egypte), the study of many aspects of ancient Egypt became more scientifically oriented. The British captured Egypt from the French and gained the Rosetta Stone. Modern Egyptology is generally perceived as beginning about 1822.

Modern Egyptology

Jean François Champollion and Ippolito Rosellini were some of the first Egyptologists of wide acclaim. The German Karl Richard Lepsius was an early participant in the investigations of Egypt; mapping, excavating, and recording several sites. Champollion announced his general decipherment of the system of Egyptian hieroglyphics for the first time, employing the Rosetta Stone as his primary aid. The Stone's decipherment was a very important development of Egyptology. With subsequently ever-increasing knowledge of Egyptian writing and language, the study of Ancient Egyptian civilisation was able to proceed with greater academic rigour and with all the added impetus that comprehension of the written sources was able to engender. Egyptology became more professional via work of William Matthew Flinders Petrie, among others. Petrie introduced techniques of field preservation, recording, and excavating. Howard Carter's expedition brought much acclaim to the field of Egyptology.

Around 1830, Rifa'a el-Tahtawi was one of the first main scholars of Egyptian Egyptology. He was inspired by the work of Muslim Egyptologists in medieval Egypt, though modern Egyptian Egyptology developed slowly compared to its Western scholars, primarily because of Islamic identity. Islamic and modern Egyptian civilization has been influenced by the pre-Islamic Egyptian culture with which Egyptology is concerned.

In the Modern era, the Supreme Council for Antiquities control excavation permits for Egyptologists to conduct their work. The field can now use geophysical methods and other applications of modern sensing techniques to further Egyptology. The Egyptian languages (such as Hieratics and Coptic) and the Egyptian writing systems are still of importance in Egyptology.

Egyptology has attracted various pseudoscientific theories of which most are widely discounted by many Egyptologists. This includes esoteric, or extraterrestrial, subjects which are considered pseudohistorical overall; few in Egyptology entertain views of the "New Age", ufology, occultism, "secret societies", or Atlantis ideas.

See also

- Assyriology

- Iranology

- List of Egyptologists

- List of writers about Egypt till the 19th century

-

- Categories

- Austrian Egyptologists, English Egyptologists, Canadian Egyptologists, American Egyptologists, Australian Egyptologists, Dutch Egyptologists, British Egyptologists, Belgian Egyptologists, Prussian Egyptologists, Scottish Egyptologists

-

- Contributing studies

- Archaeology, Anthropology, Chronology, Philology, Language studies, Epigraphy, Social history, Ethnoarchaeology, Art history, Archaeoastronomy, Architecture, Oriental studies, Biblical studies

-

- Other

- Egyptomania, Excavation, Artifacts

References

- ↑ Woods, Thomas. How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization, p 4 & 109. (Washington, DC: Regenery, 2005); ISBN 0-89526-038-7.

Further reading

- David, Rosalie. Religion and magic in ancient Egypt. Penguin Books, 2002. ISBN 0-14-026252-0

- Jacq, Christian. Magic and mystery in ancient Egypt. Souvenir Press, 1998. ISBN 0-285-63462-3

- Manley, Bill (ed.). The Seventy Great Mysteries of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05123-2

- Mertz, Barbara. Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt. Dodd Mead, 1978. ISBN 0-396-07575-4

- Mertz, Barbara. Temples, Tombs and Hieroglyphs: A Popular History of Ancient Egypt. Bedrick, 1990. ISBN 0-87226-223-5

- Mysteries of Egypt. National Geographic Society, 1999. ISBN 0-7922-9752-0

External links

- Encyclopedia of Egyptology at UCLA

- Mysteries of Egypt. Canadian Museum of Civilization

- Official Website for Dr. Zahi Hawass

- Catchpenny Mysteries of Ancient Egypt.

- Gray, Martin, The Great Pyramid, Egypt. 2005.

- Dörnenburg, Frank, Mysteries of the Past. 2004.

- Theban Mapping Project

- The Hall of Ma'at

- Glyphdoctors: Online courses in Egyptology and other resources

- The Antiquity of Man Exploring human evolution and the dawn of civilisation

- Egyptology - Ancient Near East .net - a collection of links to online Egyptology resources

- The Society for the Study of Ancient Egypt

- The Society for the Study of Ancient Egyptian Antiquities, Canada

- Sussex Egyptology Society Online

- Egypt Antiquity News Service

- Ancient Egyptian Hairstyles

- Akhet, the Horizon - Ancient Egyptian Religion

- List of web sites for museums whose primary focus is on Egyptology at the Open Directory Project

|

|||||||