Easement

|

| Property law |

|---|

| Part of the common law series |

| Acquisition |

| Gift · Adverse possession · Deed Conquest · Discovery · Accession Lost, mislaid, and abandoned property Treasure trove · Bailment · License Alienation |

| Estates in land |

| Allodial title · Fee simple · Fee tail Life estate · Defeasible estate Future interest · Concurrent estate Leasehold estate · Condominiums |

| Conveyancing |

| Bona fide purchaser Torrens title · Strata title Estoppel by deed · Quitclaim deed Mortgage · Equitable conversion Action to quiet title · Escheat |

| Future use control |

| Restraint on alienation Rule against perpetuities Rule in Shelley's Case Doctrine of worthier title |

| Nonpossessory interest |

| Easement · Profit Covenant Equitable servitude |

| Related topics |

| Fixtures · Waste · Partition Riparian water rights Prior-appropriation water rights Lateral and subjacent support Assignment · Nemo dat Property and conflict of laws |

| Other common law areas |

| Contract law · Tort law Wills, trusts and estates Criminal law · Evidence |

An easement is the right to use the real property of another without possessing it. Easements are helpful for providing pathways across two or more pieces of property or allowing an individual to fish in a privately owned pond. An easement is considered as a property right in itself at common law and is still treated as a type of property in most jurisdictions.

The rights of an easement holder vary substantially among jurisdictions. Historically, the common law courts would enforce only four types of easement:

- The right-of-way (easements of way),

- Easements of support (pertaining to excavations),

- Easements of "light and air",

- Rights pertaining to artificial waterways.

Modern courts recognize more varieties of easements, but these original categories still form the foundation of easement law.

Contents |

Basic terms

Affirmative and negative easements

An affirmative easement is the right to use another's property for a specific purpose, while a negative easement is a restriction of otherwise permitted activity on one's land.

For example, an affirmative easement might allow land owner A to drive their cattle over the land of B. A has an affirmative easement from B.

Conversely, a negative easement might restrict B from blocking A's mountain view by putting up a wall of trees. A has a negative easement from B.

Dominant and servient estate

Easements require the existence of at least two parties. The party gaining the benefit of the easement is the dominant estate, while the party granting the benefit is the servient estate.

For example, the owner of parcel A holds an easement to use a driveway on parcel B to gain access to A's house. Here, parcel A is the dominant estate, receiving the benefit, and parcel B is the servient estate, granting the benefit.

Public and private easements

A private easement is held by private individuals or entities. A public easement grants an easement for a public use, for example, to allow the public an access over a parcel owned by an individual.

Appurtenant and in gross easements

In the U.S., an easement appurtenant is one that benefits the dominant estate and "runs with the land," i.e., an easement appurtenant transfers automatically when the dominant estate is transferred.

Conversely, an easement in gross benefits an individual or a legal entity, rather than a dominant estate. The easement can be for a personal use (an easement to use a boat ramp) or a commercial use (an easement to a railroad company to build and maintain a rail line across property). Historically, an easement in gross was neither assignable nor inheritable, but today commercial easements are freely alienable.

Floating easement

A floating easement exists when there is no fixed location, route, method, or limit to the right of way.[1][2][3] For example, a right of way may cross a field, without any visible path, or allow egress through another building for fire safety purposes. A floating easement may be public or private, appurtenant or in gross.[4]

One case defined it as: "(an) easement defined in general terms, without a definite location or description, is called a floating or roving easement...."[5] Furthermore, "a floating easement becomes fixed after construction and cannot thereafter be changed."[6]

Structural encroachment

Some legal scholars classify structural encroachments as a type of easement.

Creation

Easements are generally created by express language. Parties generally grant an easement to another, or reserve an easement for themselves. Creating an easement can be as simple as having a conversation with another party, but courts have also recognized many other types of easements.

Implied and express easement

An easement may be implied or express. An express easement may be "granted" or "reserved" in a deed or other legal instrument. Alternatively, it may be incorporated by reference to a subdivision plan by "dedication", or in a restrictive covenant in the agreement of an owners association.

Implied easements are more complex and are found by courts based on the use of a property and the intention of the original parties. Implied easements are not recorded or explicitly stated, but reflect the practices and customs of use for a property. Courts typically refer to the intent of the parties, as well as prior use, to grant an implied easement.

Easement by necessity

Despite the name, necessity alone is an insufficient claim to create any easement. Parcels without access to a public way may have an easement of access over adjacent land if crossing that land is absolutely necessary to reach the landlocked parcel and there has been some original intent to provide the lot with access and but the grant was never completed or recorded but thought to exist. A court order is necessary and the judge will weigh the relative impact of enforcing an easement on the lot othewrwise unencumbered against the damage to the lot now found to be without a valid easement and thus landlocked. Because this easement requires imposing an easement upon another party for the benefit of the landlocked owner, the court shall look to the original circumstances in weighing the relative apportionment of benefit and burden to both lots in making its equitable determination whether such easement shall be created by the court. This easement, being an active creation by a court of an otherwise non-existent right, will be automatically extinguished upon termination of the necessity (for example, if a new public road is built adjacent to the landlocked tenement or another easement is acquirted without regard to comparison of ease or practicallity between the imposed easement and any valid substitute).

There is also an unwritten form of easement referred to as an implied easement, arising from the original subdivision of the land for continuous and obvious use of the adjacent parcel (e.g., for access to a road, or to a source of water)such as the right of lot owners in a subdivision to use the roadway on the approved subdivision plan without requiring a specific grant of easement to each new lot when first conveyed. An easement by necessity is distinguished from an easement by implication in that the easement by necessity arises only when "strictly necessary," whereas the latter can arise when "reasonably necessary." Easement by necessity is a higher standard by which to imply an easement.

As an example, some U.S. state statutes grant a permanent easement of access to any descendant of a person buried in a cemetery on private property.

In some states, such as New York, this type of easement is called an easement of necessity.[7]

Easement by prior use

An easement may also be created by prior use. Easements by prior use are based on the idea that land owners can intend to create an easement, but forget to include it in the deed.

There are five elements to establish an easement by prior use:

- Common ownership of both properties at one time

- Followed by a severance

- Use occurs before the severance and afterward

- Notice

- Not simply visibility, but apparent or discoverable by reasonable inspection (e.g. the hidden existence of a sewer line that a plumber could identify may be notice enough)

- Necessary and beneficial

- Reasonably necessary

- Not the "strict necessity" required by an easement by necessity

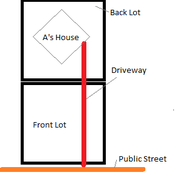

Example

A owns 2 lots. One lot has access to a public street and the second is tucked behind it and fully landlocked. A's driveway leads from the public street, across the first lot and onto the second lot to A's house. A then sells off the first lot but forgets to reserve a driveway easement in the deed.

A originally had common ownership of both properties. A also used the driveway during this period. A then severed the land. Although A did not reserve an easement, the driveway is obviously on the property and a reasonable buyer would know what it is for. Finally, the driveway is reasonably necessary for a residential plot; how else could A get to the street?

Here, there is an implied easement.

Easement by prescription

Easements by prescription, also called prescriptive easements, are implied easements granted after the dominant estate has used the property in a hostile, continuous and open manner for a statutorily prescribed number of years. Prescriptive easements differ from adverse possession by not requiring exclusivity.

Once they become legally binding, easements by prescription hold the same legal weight as written or implied easements. But, before they become binding, they hold no legal weight and are broken if the true property owner acts to defend his ownership rights. Easement by prescription is typically found in legal systems based on common law, although other legal systems may also allow easement by prescription.

Laws and regulations vary among local and national governments, but some traits are common to most prescription laws.

- open and notorious(i.e. obvious to anyone),

- actual, continuous (i.e., uninterrupted for the entire required time period),

- adverse to the rights of the true property owner

- hostile (i.e. in opposition to the claim of another. This can be accidental, not "hostile" in the common sense)

- continuous for a statutorily defined period of time

Unlike fee simple adverse possession, prescriptive easements typically do not require exclusivity. In states that do, such as Virginia, the exclusivity requirement has been interpreted to mean that the prescriptive user must use the easement in a way that is different than the general public, i.e. a use that is "exclusive" to that user, Callahan v. White, 238 Va. 10, 381 S.E.2d 1 (1989).

The period of continuous use for a prescriptive easement to become binding is generally between 5 and 30 years depending upon local laws (usually based on the statute of limitations on trespass). Generally, if the true property owner acts to defend his property rights at any time during the required time period the hostile use will end, claims on adverse possession rights are voided, and the continuous use time period resets to zero.

In some jurisdictions, if the use is not hostile but given actual or implied consent by the legal property owner, the prescriptive easement may become a regular or implied easement rather than a prescriptive easement and immediately becomes binding. In other jurisdictions, such permission immediately converts the easement into a terminable license, or restarts the time for obtaining a prescriptive easement.

Government owned property held for common use is generally immune from prescriptive easement in most cases, but some other types of government owned property may be subject to prescription in certain instances. In New York, such government property is subject to a longer statute of limitations of action, 20 years instead of 10 years for private property.

Prescription may also be used to end an existing legal easement. For example, if a servient tenement holder were to erect a fence blocking a legally deeded right-of-way easement, the dominant tenement holder would have to act to defend his easement rights during the statutory period or the easement might cease to have legal force, even though it would remain a deeded document.

Easement by estoppel

When a property owner misrepresents the existence of an easement while selling a property and does not include an express easement in the deed to the buyer, the court may step in and create an easement. Easements by estoppel generally look to any promises not made in writing, any money spent by the benefiting party in reliance on the representations of the burdened party. If the court finds that the buyer acted in good faith and relied on the seller's promises, the court will create an easement by estoppel.

For example: Ray sells land to Joe on the promise that Joe can use Ray's driveway and bridge to the main road at anytime, but Ray does not include the easement in the deed to the land. Joe, deciding that the land is now worth the price, builds a house and connects a garage to Ray's driveway. If Ray (or his successors) later decides to gate off the driveway and prevents Joe (or Joe's successors) from accessing the driveway, a court would likely find an easement by estoppel.

Because Joe purchased the land assuming that there would be access to the bridge and the driveway and Joe then paid for a house and a connection, Joe can be said to rely on Ray's promise of an easement. Ray materially misrepresented the facts to Joe. In order to preserve equity, the court will likely find an easement by estoppel.

On the other hand, if Ray had offered access to the bridge and driveway after selling Joe the land, there may not be an easement by estoppel. In this instance, it is merely inconvenient if Ray revokes access to the driveway. Joe did not purchase the land and build the house in reliance on access to the driveway and bridge. Joe will need to find a separate theory to justify an easement.

Easement by the government

In the United States, easements may be acquired by the government using its power of "eminent domain" in a "condemnation" proceeding in the courts. Note that in the U.S., in accordance with the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, property cannot simply be taken by the government unless the property owner is compensated for the fair market value of what is taken. This is true whether the government acquires full ownership of the property ("fee title") or a lesser property interest, such as an easement.

A similar right to property would appear to exist in the law of England and Wales following the incorporation of the European Convention on Human Rights into English law, in that any deprivation of the rights of the owner of property must be "in accordance with law" as well as "necessary in a democratic society" and "proportionate".

Easements distinguished from licenses

Licenses to use property in a non-possessory manner are very similar to easements and are, under certain circumstances, transformed into easements by the court, but some general differences do exist:

- A license is often revocable and is typically limited in duration

- A license is often uninsurable

- A license is often not recorded

Easements are regarded as a more powerful type of license, and a license that has any of the properties of an easement may be bound by the higher standards for termination granted by an easement.

Termination

A party claiming termination should show one or more of the following factors:

- Release: agreement to terminate by the grantor and the grantee of the easement

- Expiration: the easement reaches a formal expiration date

- Abandonment: the holder demonstrates intent to discontinue the easement[8]

- Merger: When one owner gains title to both dominant and servient tenement

- Mortgaged properties with merged easements that then go into foreclosure can cause the easement to revive when the bank takes possession of part of the dominant estate

- Necessity: If the easement was created by necessity and the necessity no longer exists

- Estoppel: The easement is unused and the servient estate takes some action in reliance on the easement's termination

- Prescription: The servient estate reclaims the easement with actual, open, hostile and continuous use of the easement

- Condemnation: The government exercises eminent domain of the land is officially condemned

- Death: The owner of an easement in gross

Rights

The following rights are recognized of an easement:

- Right to light, also called solar easement. The right to receive a minimum quantity of light in favour of a window or other aperture in a building which is primarily designed to admit light.

- Aviation easement. The right to use the airspace above a specified altitude for aviation purposes. Also known as avigation easement, where needed for low-altitude spraying of adjacent agricultural property.

- Railroad easement.

- Utility easement including:

- Storm drain or storm water easement. The easement carry rainwater to a river, wetland, detention pond, or other body of water.

- Sanitary sewer easement. The easement carry used water to a sewage treatment plant.

- Electrical power line easement.

- Telephone line easement.

- Fuel gas pipe easement.

- Sidewalk easement. Usually sidewalks are in the public right-of-way, but sometimes they are on the lot.

- View easement. Prevents someone from blocking the view of the easement owner, or permits the owner to cut the blocking vegetation on the land of another.

- Driveway easement, also known as easement of access. Some lots do not border a road, so an easement through another lot must be provided for access. Sometimes adjacent lots have "mutual" driveways that both lot owners share to access garages in the backyard. The houses are so close together that there can only be a single driveway to both backyards. The same can also be the case for walkways to the backyard: the houses are so close together that there is only a single walkway between the houses and the walkway is shared. Even when the walkway is wide enough, easement may exist to allow for access to the roof and other parts of the house close to a lot boundary. To avoid disputes, such easement should be recorded in each property deed.

- Beach access. Some jurisdictions permit residents to access a public lake or beach by crossing adjacent private property. Similarly, there may be a private easement to cross a private lake to reach a remote private property, or an easement to cross private property during high tide to reach remote beach property on foot.

- Dead end easement. Sets aside a path for pedestrians on a dead-end street to access the next public way. Could be contained in covenants of a homeowner association, notes in a subdivision plan, or directly in the deeds of the affected properties.

- Recreational easement. Some U.S. states offer tax incentives to larger landowners if they grant permission to the public to use their undeveloped land for recreational use (not including motorized vehicles). If the landowner posts the land (i.e., "No Trespassing") or prevents the public from using the easement, the tax abatement is revoked and a penalty may be assessed. Recreational easement also includes such easements as equestrian, fishing, hunting, hiking, trapping, biking (e.g., Indiana's Calumet Trail) and other such uses.

- Conservation easement. Grants rights to a land trust to limit development in order to protect the environment.

- Historic preservation easement. Similar to the conservation easement, typically grants rights to a historic preservation organization to enforce restrictions on alteration of a historic building's exterior or interior.

- Easement of lateral and subjacent support. Prohibits an adjoining land owner from digging too deep on his lot or in any manner depriving his neighbor of vertical or horizontal support on the latter's structures e.g. buildings, fences, etc.

- Communications easement. This easement can be used for wireless communications towers, cable lines, and other communications services. This is a private easement and the rights granted by the property owner are for the specific use of communications.

- Ingress/Egress easement. This easement can be used for entering and exiting a property through or over the easement area. This might be used for a person's driveway, going over another person's property.

Trespass upon easement

Blocking access to someone who has an easement is a trespass upon the right of easement and creates a cause of action for civil suit. For example, putting up a fence across a long-used public path through private property may be a trespass and a court may order the obstacle removed. Turning off the water supply to a downhill neighbor may similarly trespass on the neighbor's water easement.

Open and continuous trespassing upon an easement can lead to the extinguishment of an easement by prescription (see above), if no action is taken to cure the limitation over an extended period.

Torrens title registration

Under the Torrens title registration system of land ownership registration, easements and mortgages are recorded on the titles kept in the central land registration or cadastre. Any unrecorded easement is extinguished and no easement by prescription or implication may be claimed. Not the case in Australia, and not broadly appplicable to all common law countries.

See also

- Easements in English law

- Servitude in civil law

- Right of light

- Air rights

- Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 (in the UK)

- Crown land (see "logging and mineral rights" under Canada)

- Prior appropriation water rights

- Right of public access to the wilderness

- Riparian water rights

References

- ↑ Ballentine's Law Dictionary, p. 201.

- ↑ law.com dictionary: [1]

- ↑ Legal-explanations.com: [2]

- ↑ Example of a public floating easement, owned by the state of Florida and managed by the city of St. Augustine: [3]

- ↑ Sunnyside Valley Irrigation District v. Dickie, Docket No. 726353MAJ (Wash. 2003), citing, Berg v. Ting, 125 Wn.2d 544, 552, 886 P.2d 564 (1995), retrieved from findlaw.com [4]

- ↑ Ibid., citing Rhoades v. Barnes, 54 Wash. 145, 149, 102 P. 884 (1909).

- ↑ N.Y. Real Property Law § 335-a. Found at New York state Assemebly official website, then go to RPP. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ Ward v. Ward (1852) 7 Exch. 838

External links

- Wayleaves.com - Leading British Wayleave Consultants

- UPL (Utility Partnership Limited), UK wayleaves provider

- http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/data/constitution/amendment05/16.html (Legal Cases regarding Real Estate Taking and Easements)

- Easements and servitudes in South Africa

- Deed Of Easement Documents (UK), Deed documents outlining easements for UK properties