Aphasia

| Aphasia | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | F80.0-F80.2, R47.0 |

| ICD-9 | 315.31, 784.3, 438.11 |

| DiseasesDB | 4024 |

| MedlinePlus | 003204 |

| eMedicine | neuro/437 |

| MeSH | D001037 |

| Dysphasia | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | F80.1, F80.2, R47.0 |

| ICD-9 | 438.12, 784.5 |

Aphasia (pronounced /əˈfeɪʒə/ or pronounced /əˈfeɪziə/) is an acquired language disorder in which there is an impairment of any language modality. This may include difficulty in producing or comprehending spoken or written language.

Traditionally, aphasia suggests the total impairment of language ability, and dysphasia a degree of impairment less than total. However, the term dysphasia is easily confused with dysphagia, a swallowing disorder, and thus aphasia has come to mean both partial and total language impairment in common use.

Depending on the area and extent of brain damage, someone suffering from aphasia may be able to speak but not write, or vice versa, or display any of a wide variety of other deficiencies in language comprehension and production, such as being able to sing but not speak. Aphasia may co-occur with speech disorders such as dysarthria or apraxia of speech, which also result from brain damage.

Aphasia can be assessed in a variety of ways, from quick clinical screening at the bedside to several-hour-long batteries of tasks that examine the key components of language and communication. The prognosis of those with aphasia varies widely, and is dependent upon age of the patient, site and size of lesion, and type of aphasia.

Contents |

Classification

Classifying the different subtypes of aphasia is difficult and has led to disagreements among experts. The localizationist model is the original model, but modern anatomical techniques and analyses have shown that precise connections between brain regions and symptom classification don't exist. The neural organization of language is complicated; language is a comprehensive and complex behavior and it makes sense that it isn't the product of some small, circumscribed region of the brain.

No classification of patients in subtypes and groups of subtypes is adequate. Only about 60% of patients will fit in a classification scheme such as fluent/nonfluent/pure aphasias. There is a huge variation among patients with the same diagnosis, and aphasias can be highly selective. For instance, patients with naming deficits (anomic aphasia) might show an inability only for naming buildings, or people, or colors.[1]

Localizationist model

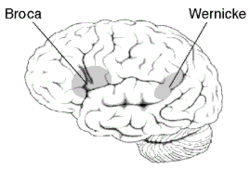

The localizationist model attempts to classify the aphasia by major characteristics and then link these to areas of the brain in which the damage has been caused. The initial two categories here were devised by early neurologists working in the field, namely Paul Broca and Carl Wernicke. Other researchers have added to the model, resulting in it often being referred to as the "Boston-Neoclassical Model". The most prominent writers on this topic have been Harold Goodglass and Edith Kaplan.

- Individuals with Broca's aphasia (also termed expressive aphasia) were once thought to have ventral temporal damage, though more recent work by Nina Dronkers using imaging and 'lesion analysis' has revealed that patients with Broca's aphasia have lesions to the medial insular cortex. Broca missed these lesions because his studies did not dissect the brains of diseased patients, so only the more temporal damage was visible. Individuals with Broca's aphasia often have right-sided weakness or paralysis of the arm and leg, because the frontal lobe is also important for body movement.

- In contrast to Broca's aphasia, damage to the temporal lobe may result in a fluent aphasia that is called Wernicke's aphasia (also termed sensory aphasia). These individuals usually have no body weakness, because their brain injury is not near the parts of the brain that control movement.

- Working from Wernicke's model of aphasia, Ludwig Lichtheim proposed five other types of aphasia, but these were not tested against real patients until modern imaging made more indepth studies available. The other five types of aphasia in the localizationist model are:

- Pure word deafness

- Conduction aphasia

- Apraxia of speech, which is now considered a separate disorder in itself.

- Transcortical motor aphasia

- Transcortical sensory aphasia

- Anomia is another type of aphasia proposed under what is commonly known as the Boston-Neoclassical model, which is essentially a difficulty with naming. A final type of aphasia, global aphasia, results from damage to extensive portions of the perisylvian region of the brain.

Other ways to Classify Aphasia

Fluent, non-fluent and "pure" aphasias

The different types of aphasia can be divided into three categories: fluent, non-fluent and "pure" aphasias.[2]

- Fluent aphasias, also called receptive aphasias, are impairments related mostly to the input or reception of language, with difficulties either in auditory verbal comprehension or in the repetition of words, phrases, or sentences spoken by others. Speech is easy and fluent, but there are difficulties related to the output of language as well, such as paraphasia. Examples of fluent aphasias are: Wernicke's aphasia, Transcortical sensory aphasia, Conduction aphasia, Anomic aphasia[2]

- Nonfluent aphasias, also called expressive aphasias are difficulties in articulating, but in most cases there is relatively good auditory verbal comprehension. Examples of nonfluent aphasias are: Broca's aphasia, Transcortical motor aphasia, Global aphasia[2]

- "Pure" aphasias are selective impairments in reading, writing, or the recognition of words. These disorders may be quite selective. For example, a person is able to read but not write, or is able to write but not read. Examples of pure aphasias are: Alexia, Agraphia, Pure word deafness[2]

Primary and secondary aphasia

Aphasia can be divided into primary and secondary aphasia.

- Primary aphasia is due to problems with language-processing mechanisms.

- Secondary aphasia is the result of other problems, like memory impairments, attention disorders, or perceptual problems.

Cognitive neuropsychological model

The cognitive neuropsychological model builds on cognitive neuropsychology. It assumes that language processing can be broken down into a number of modules, each of which has a specific function. Hence there is a module which recognises phonemes as they are spoken and a module which stores formulated phonemes before they are spoken. Use of this model clinically involves conducting a battery of assessments (usually from the PALPA), each of which tests one or a number of these modules. Once a diagnosis is reached as to where the impairment lies, therapy can proceed to treat the individual module.

Acquired childhood aphasia

Acquired childhood aphasia (ACA) is a language impairment resulting from some kind of brain damage. This brain damage can have different causes, such as head trauma, tumors, cerebrovascular accidents, or seizure disorders. Most, but not all authors state that ACA is preceded by a period of normal language development.[3] Age of onset is usually defined as from infancy until but not including adolescence.

ACA should be distinguished from developmental aphasia or developmental dysphasia, which is a primary delay or failure in language acquisition.[4] An important difference between ACA and developmental childhood aphasia is that in the latter there is no apparent neurological basis for the language deficit.[5]

ACA is one of the more rare language problems in children and is notable because of its contribution to theories on language and the brain.[4] Because there are so few children with ACA, not much is known about what types of linguistic problems these children have. However, many authors report a marked decrease in the use of all expressive language. Children can just stop talking for a period of weeks or even years, and when they start to talk again, they need a lot of encouragement. Problems with language comprehension are less common in ACA, and don't last as long.[6]

Signs and symptoms

People with aphasia may experience any of the following behaviors due to an acquired brain injury, although some of these symptoms may be due to related or concomitant problems such as dysarthria or apraxia and not primarily due to aphasia.

- inability to comprehend language

- inability to pronounce, not due to muscle paralysis or weakness

- inability to speak spontaneously

- inability to form words

- inability to name objects

- poor enunciation

- excessive creation and use of personal neologisms

- inability to repeat a phrase

- persistent repetition of phrases

- paraphasia (substituting letters, syllables or words)

- agrammatism (inability to speak in a grammatically correct fashion)

- dysprosody (alterations in inflexion, stress, and rhythm)

- incompleted sentences

- inability to read

- inability to write

- limited verbal output

- difficulty in naming

The following table summarizes some major characteristics of different types of aphasia:

| Repetition | Naming | Auditory comprehension | Fluency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presentation | |||

| Wernicke's aphasia | |||

| mild–mod | mild–severe | defective | fluent paraphasic |

| Individuals with Wernicke's aphasia may speak in long sentences that have no meaning, add unnecessary words, and even create new "words" (neologisms). For example, someone with Wernicke's aphasia may say, "You know that smoodle pinkered and that I want to get him round and take care of him like you want before", meaning "The dog needs to go out so I will take him for a walk". They have poor auditory and reading comprehension, and fluent, but nonsensical, oral and written expression. Individuals with Wernicke's aphasia usually have great difficulty understanding the speech of both themselves and others and are therefore often unaware of their mistakes. | |||

| Transcortical sensory aphasia | |||

| good | mod–severe | poor | fluent |

| Similar deficits as in Wernicke's aphasia, but repetition ability remains intact. | |||

| Conduction aphasia | |||

| poor | poor | relatively good | fluent |

| Conduction aphasia is caused by deficits in the connections between the speech-comprehension and speech-production areas. This might be damage to the arcuate fasciculus, the structure that transmits information between Wernicke's area and Broca's area. Similar symptoms, however, can be present after damage to the insula or to the auditory cortex. Auditory comprehension is near normal, and oral expression is fluent with occasional paraphasic errors. Repetition ability is poor. | |||

| Nominal or Anomic aphasia | |||

| mild | mod–severe | mild | fluent |

| Anomic aphasia is essentially a difficulty with naming. The patient may have difficulties naming certain words, linked by their grammatical type (e.g. difficulty naming verbs and not nouns) or by their semantic category (e.g. difficulty naming words relating to photography but nothing else) or a more general naming difficulty. Patients tend to produce grammatic, yet empty, speech. Auditory comprehension tends to be preserved. | |||

| Broca's aphasia | |||

| mod–severe | mod–severe | mild difficulty | non-fluent, effortful, slow |

| Individuals with Broca's aphasia frequently speak short, meaningful phrases that are produced with great effort. Broca's aphasia is thus characterized as a nonfluent aphasia. Affected people often omit small words such as "is", "and", and "the". For example, a person with Broca's aphasia may say, "Walk dog" which could mean "I will take the dog for a walk", "You take the dog for a walk" or even "The dog walked out of the yard". Individuals with Broca's aphasia are able to understand the speech of others to varying degrees. Because of this, they are often aware of their difficulties and can become easily frustrated by their speaking problems. It is associated with right hemiparesis, meaning that there can be paralysis of the patient's right face and arm. | |||

| Transcortical motor aphasia | |||

| good | mild–severe | mild | non-fluent |

| Similar deficits as Broca's aphasia, except repetition ability remains intact. Auditory comprehension is generally fine for simple conversations, but declines rapidly for more complex conversations. It is associated with right hemiparesis, meaning that there can be paralysis of the patient's right face and arm. | |||

| Global aphasia | |||

| poor | poor | poor | non-fluent |

| Individuals with global aphasia have severe communication difficulties and will be extremely limited in their ability to speak or comprehend language. They may be totally nonverbal, and/or only use facial expressions and gestures to communicate. It is associated with right hemiparesis, meaning that there can be paralysis of the patient's right face and arm. | |||

| Transcortical mixed aphasia | |||

| moderate | poor | poor | non-fluent |

| Similar deficits as in global aphasia, but repetition ability remains intact. | |||

| Subcortical aphasias | |||

| Characteristics and symptoms depend upon the site and size of subcortical lesion. Possible sites of lesions include the thalamus, internal capsule, and basal ganglia. | |||

Jargon aphasia is a fluent or receptive aphasia in which the patient's speech is incomprehensible, but appears to make sense to them. Speech is fluent and effortless with intact syntax and grammar, but the patient has problems with the selection of nouns. They will either replace the desired word with another that sounds or looks like the original one, or has some other connection, or they will replace it with sounds. Accordingly, patients with jargon aphasia often use neologisms, and may perseverate if they try to replace the words they can't find with sounds.

Commonly, substitutions involve picking another (actual) word starting with the same sound (e.g. clocktower - colander), picking another se

Causes

Aphasia usually results from lesions to the language-relevant areas of the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes of the brain, such as Broca's area, Wernicke's area, and the neural pathways between them. These areas are almost always located in the left hemisphere, and in most people this is where the ability to produce and comprehend language is found. However, in a very small number of people, language ability is found in the right hemisphere. In either case, damage to these language areas can be caused by a stroke, traumatic brain injury, or other brain injury. Aphasia may also develop slowly, as in the case of a brain tumor or progressive neurological disease, e.g., Alzheimer's or Parkinson's disease. It may also be caused by a sudden hemorrhagic event within the brain. Certain chronic neurological disorders, such as epilepsy or migraine, can also include transient aphasia as a prodromal or episodic symptom. Aphasia is also listed as a rare side effect of the fentanyl patch, an opioid used to control chronic pain.[7]

Treatment

There is no one treatment proven to be effective for all types of aphasias. Melodic intonation therapy is often used to treat non-fluent aphasia and has proved to be very effective in some cases.

History

The first recorded case of aphasia is from an Egyptian papyrus, the Edwin Smith Papyrus, which details speech problems in a person with a traumatic brain injury to the temporal lobe.[8]

Notable cases

See also

- Aphasiology

- Speech disorder

- Dysnomia disorder

- Aprosodia

- Dysprosody

- Glossolalia

Notes

- ↑ Kolb, Bryan; Whishaw, Ian Q. (2003). Fundamentals of human neuropsychology. [New York]: Worth. pp. 502, 505, 511. ISBN 0-7167-5300-6. OCLC 464808209.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Kolb, Bryan; Whishaw, Ian Q. (2003). Fundamentals of human neuropsychology. [New York]: Worth. pp. 502-504. ISBN 0-7167-5300-6. OCLC 464808209.

- ↑ Murdoch, B. E. (1990). Acquired neurological speech/language disorders in childhood. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-85066-490-X. OCLC 21976166.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Woods, Bryan T. (1995). "Acquired childhood aphasia". In Kirshner, Howard S.. Handbook of neurological speech and language disorders. New York: M. Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-9282-3. OCLC 31075598.

- ↑ Paquier, P.F.; van Dongen (1998). "Is Acquired Childhood Aphasia Atypical?". In Basso, Anna; Coppens, Patrick; Lebrun, Yvan. Aphasia in atypical populations. Hillsdale, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-1738-7. OCLC 37712996.

- ↑ Baker, Lorian; Cantwell, Dennis P. (1987). Developmental speech and language disorders. New York: Guilford Press. ISBN 0-89862-400-2. OCLC 14520470.

- ↑ "Fentanyl Transdermal Official FDA information, side effects and uses.". Drug Information Online. http://www.drugs.com/pro/fentanyl-transdermal.html#A02A9CB6-35CF-4F01-A980-C3733E0F861A.

- ↑ McCrory PR, Berkovic SF (December 2001). "Concussion: the history of clinical and pathophysiological concepts and misconceptions". Neurology 57 (12): 2283–9. PMID 11756611. http://www.neurology.org/cgi/content/abstract/57/12/2283.

- ↑ Richardson, Robert G. (1995). Emerson: the mind on fire: a biography. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08808-5. OCLC 31206668.

References

Handbooks

- Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA) Handbook (Northwestern University)

- Lass, Norman J. (1988). Handbook of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book. ISBN 1-55664-037-4. OCLC 18543553.

- Kent, Raymond D. (1994). Reference manual for communicative sciences and disorders: speech and language. Austin, Tex: Pro-Ed. ISBN 0-89079-419-7. OCLC 28889985.

Bibliographic Databases

Specialized Bibliographies

- MD Consult

- Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection

- Health Reference Complete (Academic)

Academic references

- Dr. Kalina Christoff, The Cognitive Neuroscience of Thought Laboratory publication

- Chapey, Roberta (2008). Language intervention strategies in aphasia and related neurogenic communication disorders. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-6981-7. OCLC 173201745.

- Barresi, Barbara; Goodglass, Harold; Kaplan, Edith (2001). The assessment of aphasia and related disorders. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-03604-1. OCLC 43650748.

- Coltheart, Max; Kay, Janice; Lesser, Ruth (1992). PALPA psycholinguistic assessments of language processing in aphasia. Hillsdale, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-86377-166-1. OCLC 221303581.

- Risser, Anthony H.; Spreen, Otfried (2003). Assessment of aphasia. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514075-3. OCLC 474049850.

- Jürgen Tesak; Christopher Code (2008). Milestones in the History of Aphasia: Theories and Protagonists (Brain Damage, Behaviour, and Cognition). East Sussex: Psychology Press. ISBN 1-84169-513-0. OCLC 165957752.

- Leonard L., PhD. Lapointe (2004). Aphasia And Related Neurogenic Language Disorders. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers. ISBN 1-58890-226-9. OCLC 57071469.

- Byng, Sally; Duchan, Judith F.; Felson Duchan, Judith (2004). Challenging Aphasia Therapies: Broadening the Discourse and Extending the Boundaries. East Sussex: Psychology Press. ISBN 1-84169-505-X. OCLC 473789757.

- De Bleser, Ria; Papathanasiou, Ilias (2003). The sciences of aphasia from therapy to theory. Amsterdam: Pergamon. ISBN 0-585-47448-6. OCLC 53277297.

Personal experiences of aphasia

- Sheila Hale (2002). The man who lost his language. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9361-8. OCLC 50099900.

- Stephanie Mensh; Berger, Paul D.; Whitaker, Julian M. (2002). How to conquer the world with one hand-- and an attitude. Positive Power Pub. ISBN 0-9668378-7-8. OCLC 52445790.

- Cindy Greatrex (2005) Aphasia in the Deaf Community.

- Dardick, Geeta (1991), Prisoner of Silence, Reader's Digest, June issue

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||