Duel

As practiced from the 11th to 20th centuries in Western societies, a duel is an engagement in combat between two individuals, with matched weapons in accordance with their combat doctrines. In the modern application, the term is applied to aerial warfare between fighter pilots. A battle between two warships is also referred to as a duel or a naval duel, especially in the Age of Sail when such encounters were more common.

The Romantic depiction of medieval duels was based on either a pretext of defence of honour, usually accompanied by a trusted representative (who might themselves fight, often in contravention of the duelling conventions), or as a matter of challenge of the champion which developed out of the desire of one party (the challenger) to redress a perceived insult to his sovereign's honour. The goal of the honourable duel was often not so much to kill the opponent as to gain "satisfaction", that is, to restore one's honour by demonstrating a willingness to risk one's life for it.

Duels may be distinguished from trials by combat, in that duels were not used to determine guilt or innocence, nor were they official procedures. Indeed, from the early 17th century duels were often illegal in Europe, though in most societies where duelling was socially accepted, participants in a fair duel were not prosecuted, or if they were, were not convicted.[1] Only gentlemen were considered to have honour, and duels were reserved for social equals. Commoners might duel one another occasionally,[2] but if a gentleman's honour were offended by a person of lower class, he would not duel him, but would beat him with a cane, riding crop, a whip or have his servants do so. Formal duelling is now virtually never practiced.

Contents |

Rules

Duels could be fought with some sort of sword or, from the 18th century on, with pistols.[3] For this end special sets of duelling pistols were crafted for the wealthiest of noblemen.

The traditional situation that led to a duel often happened after the offence. Whether real or imagined, one party would demand satisfaction from the offender.[4] One could signal this demand with an inescapably insulting gesture, such as throwing his glove before him, hence the phrase "throwing down the gauntlet". This originates from medieval times, when a knight was knighted. The knight-to-be would receive the accolade of three light blows on the shoulder with a sword and, in some cases, a ritual slap in the face, said to be the last affronts he could accept without redress.[5] Therefore, any one being slapped with a glove was considered—like a knight—obligated to accept the challenge or be dishonoured. Contrary to popular belief, hitting one in the face with a glove was not a challenge, but could be done after the glove had been thrown down as a response to the one issuing the challenge. Each party would name a trusted representative (a second) who would, between them, determine a suitable "field of honour." It was also the duty of each party's second to check that the weapons were equal and that the duel was fair. In the 16th and early 17th centuries, it was normal practice for the seconds as well as the principals to fight each other. Later the seconds' role became more specific, to make sure the rules were followed and to try to achieve reconciliation,[6] but as late as 1777 the Irish code still allowed the seconds an option to exchange shots.

The chief criteria for choosing the field of honour were isolation, to avoid discovery and interruption by the authorities, and jurisdictional ambiguity, also to avoid legal consequences. Islands in rivers dividing two jurisdictions were popular duelling sites; the cliffs below Weehawken on the Hudson River where the Hamilton-Burr duel occurred were a popular field of honour for New York duellists because of the uncertainty whether New York or New Jersey jurisdiction applied. Duels traditionally took place at dawn, when the poor light would make the participants less likely to be seen, and to force an interval for reconsideration or sobering-up. For some time before the mid-18th century, swordsmen duelling at dawn so often carried lanterns to see each other that fencing manuals integrated them into their lessons, using the lantern to parry blows and blind the opponent.[7] The manuals sometimes show the combatants carrying the lantern in the left hand wrapped behind the back, which is still one of the traditional positions for the off hand in modern fencing.[8]

At the choice of the offended party, the duel could be

- to first blood, in which case the duel would be ended as soon as one man was wounded, even if the wound were minor:

- until one man was so severely wounded as to be physically unable to continue the duel;

- to the death, in which case there would be no satisfaction until one party was mortally wounded;

- or, in the case of pistol duels, each party would fire one shot. If neither man was hit and if the challenger stated that he was satisfied, the duel would be declared over. A pistol duel could continue until one man was wounded or killed, but to have more than three exchanges of fire was considered barbaric and, if no hits were achieved, somewhat ridiculous.

Under the latter conditions, one or both parties could intentionally miss in order to fulfill the conditions of the duel, without loss of either life or honour. However, to do so, "to delope", could imply that your opponent was not worth shooting. This practice occurred despite being expressly banned by the Code Duello of 1777. Rule 13 stated: "No dumb shooting or firing in the air is admissible in any case... children's play must be dishonourable on one side or the other, and is accordingly prohibited." Practices varied, however, and many pistol duels were to first blood or death. The offended party could stop the duel at any time if he deemed his honour satisfied. In some duels there were seconds (stand-ins) who, if the primary dueller were not able to finish the duel, would then take his place. This was usually done in duels with swords, where one's expertise was sometimes limited. The second would also act as a witness.

For a pistol duel, the parties would be placed back to back with loaded weapons in hand and walk a set number of paces, turn to face the opponent, and shoot. Typically, the graver the insult, the fewer the paces agreed upon. Alternatively, a pre-agreed length of ground would be measured out by the seconds and marked, often with swords stuck in the ground (referred to as "points"). At a given signal, often the dropping of a handkerchief, the principals could advance and fire at will. This latter system reduced the possibility of cheating, as neither principal had to trust the other not to turn too soon. Another system involved alternate shots being taken—the challenged firing first.

Many historical duels were prevented by the difficulty of arranging the "methodus pugnandi". In the instance of Dr. Richard Brocklesby, the number of paces could not be agreed upon; and in the affair between Mark Akenside and Ballow, one had determined never to fight in the morning, and the other that he would never fight in the afternoon. John Wilkes, who did not stand upon ceremony in these little affairs, when asked by Lord Talbot how many times they were to fire, replied, "just as often as your Lordship pleases; I have brought a bag of bullets and a flask of gunpowder."

History

Physical confrontations related to insults and social standing surely pre-date Homo sapiens, but the formal concept of a duel, in Western society, developed out of the mediaeval judicial duel and older pre-Christian practices such as the Viking Age Holmganga. Judicial duels were deprecated by the Lateran Council of 1215. However, in 1459 (MS Thott 290 2) Hans Talhoffer reported that in spite of Church disapproval, there were nevertheless seven capital crimes that were still commonly accepted as resolvable by means of a judicial duel. Most societies did not condemn duelling, and the victor of a duel was regarded not as a murderer but as a hero; in fact, his social status often increased. During the early Renaissance, duelling established the status of a respectable gentleman, and was an accepted manner to resolve disputes. Duelling in such societies was seen as an alternative to less regulated conflict.

According to one scholar, "In France during the reign of Henry IV (1589–1610), more than 4,000 French aristocrats were killed in duels in an eighteen-year period...During the reign of Louis XIII (1610–1643)...in a twenty-year period 8,000 pardons were issued for murders associated with duels...In the United States thousands of Southerners died protecting what they believed to be their honor."[9]

The first published code duello, or "code of duelling", appeared in Renaissance Italy; however, it had many antecedents, ranging back to old Germanic law. The first formalised national code was France's, during the Renaissance. In 1777, Ireland developed a code duello, which was indeed the most influential in American duelling culture.

Prominent duels

To decline a challenge was often equated to defeat by forfeiture, and sometimes regarded as dishonourable. Prominent and famous individuals were especially at risk of being challenged.

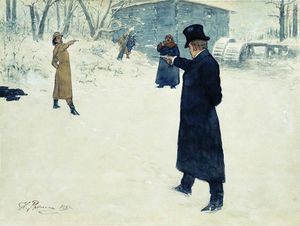

The Russian poet Alexander Pushkin prophetically described a number of duels in his works, notably Onegin's duel with Lensky in Eugene Onegin. The poet was mortally wounded in a controversial duel with Georges d'Anthès, a French officer rumoured to be his wife's lover. D'Anthès, who was accused of cheating in this duel, married Pushkin's sister-in-law and went on to become French minister and senator.

In 1598 the English playwright Ben Jonson fought a duel, mortally wounding an actor by the name of Gabriel Spencer. In 1798 HRH The Duke of York, well known as "The Grand Old Duke of York", duelled with Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Lennox and was grazed by a bullet along his hairline. In 1840 the 7th Earl of Cardigan, officer in charge of the now infamous Charge of the Light Brigade, fought a duel with a British Army officer by the name of Captain Tuckett. Tuckett was wounded in the engagement, though not fatally.

Four Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom have engaged in duels (although only Pitt and Wellington held the office at the time of their duels):

- William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne v Colonel Fullarton (1780)

- William Pitt the Younger v George Tierney (1798)

- George Canning v Lord Castlereagh (1809)

- The Duke of Wellington v Lord Winchelsea (1829)

In 1864, American writer Mark Twain—then editor of the New York Sunday Mercury—narrowly avoided fighting a duel with a rival newspaper editor, apparently through the quick thinking of his second, who exaggerated Twain's prowess with a pistol.[10][11][12]

The most notorious American duel was the Burr-Hamilton duel, in which notable Federalist Alexander Hamilton was fatally wounded by his political rival, the sitting Vice President of the United States Aaron Burr. Another American politician, Andrew Jackson, later to serve as a General Officer in the U.S. Army and to become the seventh U.S. president, fought two duels, though some legends claim he fought many more. On May 30, 1806, he killed prominent duellist Charles Dickinson, suffering himself from a chest wound which caused him a lifetime of pain. Jackson also reportedly engaged in a bloodless duel with a lawyer and in 1803 came very near duelling with John Sevier; In 1813 Jackson engaged in a frontier brawl, which does not count as a duel, with Senator Thomas Hart Benton.

On 30 May 1832, French mathematician Évariste Galois was mortally wounded in a duel at the age of twenty, the day after he had written his seminal mathematical results.

The last fatal duel in Canada, in 1833, saw Robert Lyon challenge John Wilson to a pistol duel after a quarrel over remarks made about a local school-teacher—whom Wilson ended up marrying after Lyon was killed in the duel. The last fatal duel in England took place on Priest Hill, between Englefield Green and Old Windsor, on 19 October 1852, between two French refugees, Cournet and Barthelemy, the former being killed. [13]

Unusual duels

In 1808, two Frenchmen are said to have fought in balloons over Paris, each attempting to shoot and puncture the other's balloon; one duellist is said to have been shot down and killed with his second.[14]

Thirty-five years later (1843), two men are said to have fought a duel by means of throwing billiard balls at each other.[14]

Some participants in a duel, given the choice of weapons, are said to have deliberately chosen ridiculous weapons such as howitzers, sledgehammers, or forkfuls of pig dung, in order to show their disdain for duelling.[14]

Isaac Asimov relates a joke in his Treasury of Humor (1971) that claims that Otto von Bismarck challenged Rudolf Virchow to a duel. As the challenged party had the choice of weapons, Virchow chose two sausages, one of which had been infected with cholera. Bismarck is said to have called off the duel at once.[15]

Single combat

Single combat is a duel between two single warriors which takes place in the context of a battle between two armies, with the two often considered the champions of their respective sides. Typically, it takes place in the no-man's-land between the opposing armies, with other warriors watching and themselves refraining from fighting until one of the two single combatants has won.

Single combats are attested at numerous periods and places, in both myth and the depiction of actual war. Duels between individual warriors are depicted in the Iliad, including those between Menelaus and Paris and later between Achilles and Hector. Single combat is mentioned quite frequently in the history of Ancient Rome: the Horatii's defeat of the Alba Longan Curiatii in the 7th century BC is reported by Livy to have settled a war in Rome's favor and subjected Alba Longa to Rome; Marcus Claudius Marcellus took the spolia opima from Viridomarus, king of the Gaesatae, at the Battle of Clastidium (222 BC); and Marcus Licinius Crassus Dives from Deldo, king of the Bastarnae (29 BC).

Depictions of single combat also appear in the Hindu epics of the Mahābhārata and the Ramayana. Single combats are often preludes to battles in the Chinese epic Romance of the Three Kingdoms and are featured prominently throughout the epic.

In The Cattle Raid of Cooley, a famous episode of Irish Mythology, all warriors of Ulster but Cúchulainn are affected by a curse and unable to fight the invading army of Queen Maeb - leaving Cúchulainn to fight a whole series of single combats by himself until they recover.

Many battles depicted in the mediaeval Chanson de Roland consist of a series of single combats, as are battles depicted in various tales of the Arabian Nights. Guy of Warwick, the legendary English Romance hero, is depicted as defeating in single combat the Viking giant Colbrand; the story is set in the time of Athelstan of England, but actually reflects the society of the late Middle Ages.

An important episode in Geoffrey of Monmouth's legendary History of the Kings of Britain (ca. 1136) is the single combat between prince Nennius of Britain and Julius Caesar.

Single combat was also a prelude to battles in pre-Islamic Arabia and early Islamic battles. For example, at the Battle of Badr, one of the most important in the early history of Islam, was opened by three champions of the Islamic side (Ali, Ubaydah, and Hamzah) stepping forward, engaging and defeating three of the then-Pagan Meccans, although Ubaydah was mortally wounded.[16] This result of the three single combats was considered to have substantially contributed to the Muslim victory in the overall battle which followed. Duels were also part of other battles at the time of Muhammad, such as the battle of Uhud, battle of the Trench and the battle of Khaybar.

Single combats were a major characteristic in the traditional Samurai fighting of medieval Japan, and the samurai despised the mass fighting style of the Mongols who invaded their country and saw it as inferior (see Mongol invasions of Japan#Significance).

The 1380 Battle of Kulikovo, a key event in the wars between the Tartaro-Mongols and the Russians, was allegedly opened by a single combat of two champions: the Russian Alexander Peresvet, and the Golden Horde's Temir-murza (also Chelubey or Cheli-bey). The champions killed each other in the first run, though according to Russian legend, Peresvet did not fall from the saddle, while Temir-murza fell.

In personal combat fought on the backs of war elephants in a war between Burma and Siam, Siamese King Naresuan slew Burmese Crown Prince Minchit Sra in 1593.

Captain John Smith of Jamestown, in his earlier career as a mercenary in Eastern Europe, is reputed to have defeated, killed and beheaded Turkish commanders in three single combats, for which he was knighted by the Transylvanian Prince Sigismund Báthory and given a horse and coat of Arms showing three Turks' heads.[17]

Dramtist Ben Jonson, in conversations with the poet William Drummond, recounted that when serving in the Low Countries as a volunteer with the regiments of Francis Vere, he had defeated an opponent in single combat "in view of borth armies" and stripped him of his weapons.[18]

Single combats are especially common during battles fought between mounted aristocratic warriors (or earlier, driving chariots), a type of warfare allowing considerable freedom of manoeuvre and initiative to individual warriors. Single combat is less feasible where battles are fought by bodies of infantry whose success depends upon keeping an exact formation, such as the ancient phalanx and maniple and in later times the various formations of pikemen.

Duelling in particular regions

Germany, Austria, Switzerland

Historically a form of non-lethal duelling called Mensur was a tradition among students in these countries, and still exists as Academic fencing. This form of duelling is all about honour, therefore it is non-competitive.

- "a traditional way of training and educating character and personality ... there is neither winner nor loser ... the goal being less to avoid injury than to endure it stoically"

Greece

In the Ionian Islands in the 19th century, there was a practice of formalised fighting between men over points of honour.

Knives were the weapons used in such fights. They would begin with an exchange of sexually-related insults in a public place such as a tavern, and the men would fight with the intention of slashing the other's face, rather than killing. As soon as blood was drawn onlookers would intervene to separate the men. The winner would often spit on his opponent and dip his neckerchief in the blood of the loser, or wipe the blood off his knife with it.

The winner would generally make no attempt to avoid arrest and would receive a light penalty, such as a short jail sentence and/or a small fine.[19]

India

In the South Indian state of Kerala, duelling between warriors was used to settle conflicts between local rulers. The practice ended in the early 1800s following the outlaw of Kalaripayattu by British Colonialists. The prime martial caste of Kerala, Nairs, and some prominent Ezhava families made up the Chekavars (which literally means "those who are prepared to die" in the local Malayalam language). Some prominent warriors who took part in Ankam (duel) were Thacholi Othenan, Unniarcha, Aromal Chekavar, whose legends are described in the Vadukkan Pattukal (Northern Ballads). The Mamankam Festival held by the Zamorin ruler in the kingdom of modern day Calicut, was a ritual which glorified the martial traditions of warrior families in the Malabar. The ritual ended after the Zamorin was overthrown.

Ireland

In 1777, at the Summer assizes in the town of Clonmel, County Tipperary, a code of practice was drawn up for the regulation of duels. It was agreed by delegates from Tipperary, Galway, Mayo, Sligo and Roscommon, and intended for general adoption throughout Ireland. A copy of the code, known generally as 'The thirty-six commandments', was to be kept in a gentleman's pistol case for reference should a dispute arise regarding procedure.[20] An amended version known as 'The Irish Code of Honor', and consisting of twenty-five rules, was adopted in some parts of the United States. The first article of the code stated:

Rule 1.--The first offence requires the apology, although the retort may have been more offensive than the insult.--Example: A. tells B. he is impertinent, &C.; B. retorts, that he lies; yet A. must make the first apology, because he gave the first offence, and then, (after one fire,) B. may explain away the retort by subsequent apology.[21]

The 19th century statesman, Daniel O'Connell, took part in a duel in 1815. Following the death of his opponent, John D'Esterre, O'Connell repented and from that time wore a white glove on his right hand when attending Mass as a public symbol of his regret.[22]

In 1862, in an article entitled Dead (and gone) Shots, Charles Dickens recalled the rules and myths of Irish duelling in his periodical All the Year Round.[23]

Poland

In Poland duels have been known since the Middle Ages. Polish duel rules were formed, based on Italian, French and German codes. The best known Polish code was written as late as in 1919 by Władysław Boziewicz. In those times duels were already forbidden in Poland, but the "Polish Honorary Code" was quite widely in use. Punishments for participation in duels were rather mild (up to a year imprisonment if the result was death or grievous bodily harm).[24]

Philippines

Duelling is widely known to have existed for centuries in the Philippine Islands. In the Visayan islands, the offended party would first "hagit" or challenge the offender. The offender would have the choice whether to accept or decline the challenge. In the past, choice of weapons was not limited. But most often, bolos, rattan canes, and knives were the preferred weapons. Rules may be agreed upon. Duels were either first-blood, submission, or to the last man standing (last man still alive). Duels to death were known as "huego-todo" (without bounds).

Widely publicised duels are common in Filipino martial arts circles. One of those very controversial and publicised duels was between Ciriaco "Cacoy" Cañete and Venancio "Ansiong" Bacon. It was rumoured that Cacoy won in this match by executing an illegal manoeuvre, but this rumour has not been proven to this day. Another match was between Cacoy and a man identified only by his name "Domingo" in the mountain barangay of Balamban in 1948, which was also very controversial. Some claimed that this event was just a hoax.

Russia

Early History of Duelling in Russia

The European tradition of duelling and the word Duel itself was brought to Russia in the seventeenth century by European adventurers in the Russian service. It quickly became so popular that the Emperor Peter the First was forced to forbid duelling in 1715 under the threat of hanging the duellists because it could cause a lot of casualties among the commanding ranks. However, even such strict measures did not slow the spread of duelling. Before duelling arrived in Russia, there was another tradition of single combat in Slavonic countries using bare hands or steel weaponry such as swords or maces. The point was to choke the rival, break his neck or spine, or neutralize him in another way in bare-hands combat, or to kill him with a weapon. Such a procedure, historically called bash na bash (an old Russian expression, meaning one-on-one) was a traditional way to avoid the bloodshed of internecine war. It meant that leaders of both Druzhina or other armed groups, either came towards the centre of the battlefield or sent messengers to negotiate whether the two most skillful fighters or the leaders themselves would engage in single combat, usually to the death. After the fight, the winner took the army, lands and towns, including the people living there, as well as the wives, children and households of the defeated fighter. It meant that for ordinary warriors, peasants and citizens it made no difference who was in charge. If the conflict arose between Slav and non-Slav ethnic groups, such as Pechenegs, which had no intentions of ruling Slavic lands, but to rape and sack instead, there was another agreement: If the Slav fighter wins, the loser left for good and never came back, if the non-Slav won - they do what they want, and take everything what they want.

The first documented fight was described by Nestor the Chronicler in the Primary Chronicle, and it was exactly as mentioned above, with Kievian best fighter against Pecheneg's. The most notable fight was between Tmutarakan' Prince Mstislav the Brave and Kasogs Prince Rededya in 1022, in which Mstislav has defeated Rededya in fair bare hands combat, forced the Kasogs to pay tribute and built a Church. He also took Rededya's wife and two sons, baptised them as Christians and then married his daughter to Rededya's son according to the tradition of those times. This episode is also described in the Primary Chronicle. It is important to note that although he was killed, Rededya was honoured, and his children had many descendants and were considered a noble Russian family.

Along with this tradition there was another significant one, in which such combat was the opening of a general battle. The most famous example was the duel between the Russian monk St. Alexander Peresvet (Canonized by Russian Orthodox Church) and the Tatar champion Chelubey at the beginning of the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380. According to the legend, they clashed in a mounted duel and both were killed, after spearing each other with lances.

Duelling

Despite an official ban from the 17th through the 19th centuries, under penalty of death for both duellists, duelling was a significant military tradition in the Russian Empire with detailed unwritten duelling code—which was eventually written down by V.Durasov and released in print in 1908.[25] This code forbade duels between people of different ranks (Table of Ranks). For instance, an infantry captain could not challenge a major, but could easily pick on a Titular Counsellor. On the other hand, a higher ranked person could not stoop to challenge lower ranks, so it was up to his subordinates or servants to take revenge on their master's behalf.

Duelling was also common amongst prominent Russian writers, poets, and politicians. Famous Russian poet Alexander Pushkin fought 29 duels, challenging many prominent figures: writer Ivan Turgenev, count Fyodor Tolstoy, prince Nikolay Repnin and others,[26] before being killed in a duel with Georges d'Anthès, a notable French adventurer, in 1837. His poetic successor Mikhail Lermontov was killed four years later, by fellow Army officer Nikolay Martynov.

The duelling tradition died out slowly from the mid-19th century.

The formal duel was an exclusive privilege of the nobility, but common people had the various forms of "Kulachniy boy" fist fighting.

Ukraine

In the subordinated state of Ukraine, a part of Rzeczpospolita, duelling rights varied widely depending on the nobles' pro-Polish or anti-Polish stance. Native Ukrainian landlords stood in a lesser position in comparison with their Polish-descended neighbours. And even among the Ukrainian natives there was a wide gap in their rights and opportunities, depending on their partiality to Poland. For example, the prominent Ukrainian politician and military leader Bohdan Khmelnytsky was humiliated by his pro-Polish neighbour Daniel Czapliński, who seized Khmelnytsky's patrimony, killing one of his sons with a whip and raping his wife. After Khmelnytsky returned his place and discovered what had happened, he fought Czapliński in a sabre duel, but was stunned from behind and thrown into a dungeon. Later, because Czapliński was higher ranked and far more privileged than he, Bohdan appealed legally to Kazimir, the king of Rzeczpospolita, but king answered only: "You have your sabre" (see "The Uprising").

Zaporizhian Sich

Duels between Ukrainian Cossacks were a kind of ordeal for persons suspected of treason. Duels were otherwise unheard of, because all Cossacks were considered brothers, and a duel would be considered fratricidal.

Opposition to duelling

The Roman Catholic Church and many political leaders, like King James VI & I of Scotland and England, usually denounced duelling throughout Europe's history, though some authorities tacitly allowed it, believing it to relieve long-standing familial and social tensions.

United Kingdom

Even though some of the most famous duels in British history took place in the early 19th century, as referred to above, by the mid 19th century duelling was widely frowned on, and largely ceased to occur.

France

King Louis XIII of France outlawed duelling in 1626, and duels remained illegal in France ever afterwards. At least one noble was beheaded for fighting a duel during Louis's reign, and his successor Louis XIV intensified efforts to wipe out the duel. Despite these efforts, duelling continued. French officers fought 10,000 duels, leading to over 400 deaths, between 1685 and 1716.[27]

The last duel in France took place in 1967 when Gaston Deferre insulted René Ribière at the French parliament and was subsequently challenged to a duel fought with swords. René Ribière lost the duel, Deferre's sword having twice shed Ribière's blood. René Ribière was only slightly injured.[28]

Canada

Duelling is illegal in Canada, pursuant to s. 71 of the Criminal Code which states:[29]

- Everyone who:

-

- (a) challenges or attempts by any means to provoke another person to fight a duel,

-

- (b) attempts to provoke a person to challenge another person to fight a duel, or

-

- (c) accepts a challenge to fight a duel,

- is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years.

United States

History

Duelling began to fall out of favor in America in the 18th century, and the death of former United States Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton by duelling did not help its declining popularity. Benjamin Franklin denounced the practice as uselessly violent, and George Washington encouraged his officers to refuse challenges during the American Revolutionary War because he believed that the death by duelling of officers would have threatened the success of the war effort.

By the end of the 19th century, legalised duelling was almost extinct in most of the world. As shown below, some U.S. states do not have any statute or constitutional provision prohibiting duelling, though the party causing injury in a duel may be prosecuted under the applicable laws relating to bodily harm or manslaughter.

State constitutional provisions and military laws prohibiting duelling

Several states have very high-level bans laid against duelling, with stiff penalties for violation. Several United States state constitutions ban the practice, the most common penalty being disenfranchisement and/or disqualification from all offices. As well, Article 114 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice makes duelling by a member of the armed forces a military crime.

- Constitution of Alabama (Article IV, Section 86):

- "The Legislature shall pass such penal laws as it may deem expedient to suppress the evil practice of duelling."

- Constitution of Arkansas (Article XIX, Section 2)

- "No person who may hereafter fight a duel, assist in the same as second, or send, accept, or knowingly carry a challenge therefore, shall hold any office in the State, for a period of ten years; and may be otherwise punished as the law may prescribe."

- Constitution of Florida of 1838, Article 6, Section 5:

- "No person shall be capable of holding, or of being elected to any post of honor, profit, trust, or emolument, civil or military, legislative, executive, or judicial, under the government of this State, who shall hereafter fight a duel, or send, or accept a challenge to fight a duel, the probable issue of which may be the death of the challenger, or challenged, or who shall be a second to either party, or who shall in any manner aid, or assist in such duel, or shall be knowingly the bearer of such challenge, or acceptance, whether the same occur, or be committed in or out of the State."

- Constitution of Iowa (Article I, Section 5) (repealed):

- "Any citizen of this State who may hereafter be engaged, either directly, or indirectly, in a duel, either as principal, or accessory before the fact, shall forever be disqualified from holding any office under the Constitution and laws of this State." (This section was repealed by Constitutional Amendment 43 in 1992.)

- Constitution of Kentucky (Section 228 and 239):

- "Members of the General Assembly and all officers, before they enter upon the execution of the duties of their respective offices, and all members of the bar, before they enter upon the practice of their profession, shall take the following oath or affirmation: I do solemnly swear (or affirm, as the case may be) that I will support the Constitution of the United States and the Constitution of this Commonwealth, and be faithful and true to the Commonwealth of Kentucky so long as I continue a citizen thereof, and that I will faithfully execute, to the best of my ability, the office of .... according to law; and I do further solemnly swear (or affirm) that since the adoption of the present Constitution, I, being a citizen of this State, have not fought a duel with deadly weapons within this State nor out of it, nor have I sent or accepted a challenge to fight a duel with deadly weapons, nor have I acted as second in carrying a challenge, nor aided or assisted any person thus offending, so help me God."

- "Any person who shall, after the adoption of this Constitution, either directly or indirectly, give, accept or knowingly carry a challenge to any person or persons to fight in single combat, with a citizen of this State, with a deadly weapon, either in or out of the State, shall be deprived of the right to hold any office of honor or profit in this Commonwealth; and if said acts, or any of them, be committed within this State, the person or persons so committing them shall be further punished in such manner as the General Assembly may prescribe by law."

- Constitution of Mississippi (Article 3, Section 19):

- "Human life shall not be imperiled by the practice of dueling; and any citizen of this state who shall hereafter fight a duel, or assist in the same as second, or send, accept, or knowingly carry a challenge therefor, whether such an act be done in the state, or out of it, or who shall go out of the state to fight a duel, or to assist in the same as second, or to send, accept, or carry a challenge, shall be disqualified from holding any office under this Constitution, and shall be disenfranchised."

- Constitution of Oregon (Article II, Section 9)

- "Every person who shall give, or accept a challenge to fight a duel, or who shall knowingly carry to another person such challenge, or who shall agree to go out of the State to fight a duel, shall be ineligible to any office of trust, or profit."

- Constitution of South Carolina (Article XVII, Section 1B)

- "After the adoption of this Constitution any person who shall fight a duel or send or accept a challenge for that purpose, or be an aider or abettor in fighting a duel, shall be deprived of holding any office of honor or trust in this State, and shall be otherwise punished as the law shall prescribe."

- Constitution of Tennessee (Article IX, Section 3):

- "Any person who shall, after the adoption of this Constitution, fight a duel, or knowingly be the bearer of a challenge to fight a duel, or send or accept a challenge for that purpose, or be an aider or abettor in fighting a duel, shall be deprived of the right to hold any office of honor or profit in this state, and shall be punished otherwise, in such manner as the Legislature may prescribe."

- Session law of Texas (Punishing Crimes and Misdemeanor, Section 56):

- "Every person who shall be the bearer of any challenge for a duel, or shall in any way aid or assist in any duel, shall, on conviction thereof, be fined and imprisoned at the discretion of the court before whom such conviction may be had."

- Constitution of West Virginia (Article IV, Section 10)

- "Any citizen of this state, who shall, after the adoption of this constitution, either in or out of the state, fight a duel with deadly weapons, or send or accept a challenge so to do, or who shall act as a second or knowingly aid or assist in such duel, shall, ever thereafter, be incapable of holding any office of honor, trust or profit in this state."

- Uniform Code of Military Justice (Article 114):

- "Any person subject to this chapter who fights or promotes, or is concerned in or connives at fighting a duel, or who, having knowledge of a challenge sent or about to be sent, fails to report the facts promptly to the proper authority, shall be punished as a court-martial may direct."

State and territorial laws prohibiting duelling

20 states, along with the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, have some statute(s) (including constitutional provisions) specifically prohibiting duelling. The remaining 30 states either have no such statute or constitutional provision, or limit their duelling prohibition to members of their state national guard. This does not necessarily mean, however, that duelling is legal in any state, as assault and murder laws can apply. The following is a list of each state's or territory's status with respect to laws prohibiting duelling:

- Alabama – See Constitution above

- Alaska – No statutory duelling prohibition

- Arizona – No statutory duelling prohibition for civilians; prohibited for personnel of the state national guard[30]

- Arkansas – See Constitution above; specifically prohibited for personnel of the state national guard[30]

- California – No statutory duelling prohibition – California Penal Code Sections 225 through 232, repealed in 1994

- Colorado – C.R.S. 18-13-104

- Connecticut – No statutory duelling prohibition for civilians; prohibited for personnel of the state national guard[31]

- Delaware – No statutory duelling prohibition

- Florida – See Constitution above

- District of Columbia – D.C. Code 22-1302

- Georgia – No statutory duelling prohibition for civilians; prohibited for personnel of the state national guard[32]

- Hawaii – No statutory duelling prohibition for civilians; prohibited for personnel of the state national guard[33]

- Idaho – Idaho Code 19-303

- Illinois – No statutory duelling prohibition

- Indiana – No statutory duelling prohibition

- Iowa – No statutory duelling prohibition for civilians; prohibited for personnel of the state national guard[34]

- Kansas – No statutory duelling prohibition for civilians; prohibited for personnel of the state national guard[35]

- Kentucky – K.R.S. 437.030

- Louisiana – No statutory duelling prohibition

- Maine – No statutory duelling prohibition

- Maryland – No statutory duelling prohibition

- Massachusetts – G.L.Mass. ch. 265, sections 3–4

- Michigan – M.C.L.S. 750.171–750.173a; M.C.L.S. 750.319 and 750.320

- Minnesota – No statutory duelling prohibition

- Mississippi – Miss. Code Ann. Title 97, Chapter 39

- Missouri – No statutory duelling prohibition for civilians; prohibited for personnel of the state national guard[36]

- Montana – No statutory duelling prohibition

- Nebraska – No statutory duelling prohibition

- Nevada – Nev. Rev. Stat. Ann. 200.430 through 200.450

- New Hampshire – No statutory duelling prohibition

- New Jersey – No statutory duelling prohibition

- New Mexico – N.M. Stat. Ann. 30-20-11

- New York – Duelling in New York is prohibited by Penal Law section 35.15(1)(c) which provides that the permitted use of physical force in defense of a person does not apply to "the product of combat by agreement"; prohibited for personnel of the state national guard[37]

- North Carolina – No statutory duelling prohibition

- North Dakota – N.D. Cent. Code 29-03-02

- Ohio – No statutory duelling prohibition for civilians; prohibited for personnel of the state national guard[38]

- Oklahoma – 21 Okl. St., Chapter 22

- Oregon – See Constitution above; also specifically prohibited for personnel of the state national guard[39]

- Pennsylvania – No statutory duelling prohibition for civilians; prohibited for personnel of the state national guard[40]

- Puerto Rico – 33 L.P.R.A. 4035

- Rhode Island – R.I. Gen. Laws, Title 11, Chapter 12

- South Carolina – See Constitution above; 16 S.C. Code Ann., Chapter 3, Article 5

- South Dakota – No statutory duelling prohibition

- Tennessee – See Constitution above

- Texas – See Session Law above

- Utah – Utah Code Ann. 76-5-104 (homicide includes duelling and other "consensual altercations")

- Vermont – No statutory duelling prohibition

- Virginia – No specific statutory duelling prohibition, To stop duelling, Virginia's Anti-Dueling Act, passed in 1810, created civil and criminal penalties for the most usual causes of duelling. It is still on the books. Virginia Code §8.01-45 creates a Civil Action for insulting words. Virginia Code §18.2-416 makes it a crime to use abusive language to another under circumstances reasonably calculated to provoke a breach of the peace. Virginia Code §18.2-417 makes certain slander and libel a crime. see 1 VA. CODE REV. § 8 (1819), quoted in Chaffin v. Lynch, 1 S.E. 803, 806 (Va. 1887).

- Washington – No statutory duelling prohibition for civilians; prohibited for personnel of the state national guard[41]

- West Virginia – See Constitution above; W.Va. Code 61-2-18 through 61-2-25

- Wisconsin – No statutory duelling prohibition

- Wyoming – No statutory duelling prohibition

Anti-duelling pamphlets

1804 Anti-duelling sermon by an acquaintance of Alexander Hamilton |

Opening text of 1804 sermon |

Anti-Duelling Association of New York pamphlet, Remedy, 1809 |

Resolutions, Anti-Duelling Association of N.Y., from Remedy pamphlet, 1809 |

Address to the electorate, from Remedy pamphlet |

Latin America

In much of South America duels were common during the 20th century,[42] although generally illegal.

- In Mexico, April 2009, 31 year-old Joseph Berrelleza and 18 year-old Eduardo Jesús Argüelles Rábago fought a duel in the state of Sinaloa. The duellists were 5 metres apart from each other and each used his own gun. Both were seriously wounded in the encounter.[43]

- In Peru there were several high-profile duels by politicians in the early part of the twentieth century including one in 1957 involving Fernando Belaúnde Terry—who went on to become President.

- Uruguay decriminalised duelling in 1920, and in that year José Batlle y Ordóñez, a former President of Uruguay, killed Washington Beltran, editor of the newspaper El País, in a formal duel fought with pistols. In 1990 another editor was challenged to a duel by an assistant police chief.[44] Although approved by the government the duel did not take place—and in 1992 Uruguay repealed the 1920 law.

- In 2002 Peruvian independent congressman, Eittel Ramos, challenged Peruvian Vice President, David Waisman to a duel with pistols, saying the vice president had insulted him. Waisman declined.[45]

- 1952: Chile. Senator Salvador Allende (later president of Chile) was challenged to a duel by his colleague Raúl Rettig (later head of a commission that investigated human rights violations committed during the 1973–1990 military rule in Chile). Both men agreed to fire one shot at each other. Both deliberately missed.[46] At that time, duelling was already illegal in Chile.

Japan

- In May 2005, twelve youths aged between fifteen and seventeen were arrested in Japan and charged with violating a duelling law that came into effect in 1889. Six other youths were also arrested on the same charges in March.

Cinematic duels

In the world of cinema, duelling has provided themes for such motion pictures as Stanley Kubrick's 1975 Barry Lyndon (an adaptation of a novel by William Makepeace Thackeray from 1844) and Ridley Scott's 1977 The Duellists, which adapted Joseph Conrad's 1908 short story The Duel, [47] [http://www.isidore-of-seville.com/dueling/4. The 1943 film The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp shows two main characters becoming friends after fighting a duel, the preparations for which are shown in great detail. Perhaps most notable of all however, is the career of Max Ophuls, who employs duels to resolve passionate conflicts in a number of his films. In 1974's The Man with the Golden Gun the duel between Bond and Scaramanga is refereed by Nick-Nack, who tells both contestants that this is a duel to the death; no wounding is allowed and, if necessary, Nick Nack will administer the coup-de-grace.

See also

- List of famous duels

- Trial by combat, judicially-sanctioned duel

- Holmgang, a Scandinavian form of duelling

- Code duello, a set of rules for duelling

- Truel, a duel with three participants

- European duelling sword

- Duelling pistol

- Champion warfare

References

- ↑ John Albert Lynn, Giant of the Grand Siecle, p. 256, says that duelling was outlawed in 1626 in France and never again legalised, despite thousands of violations.

- ↑ Lynn, 255

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ "The Mystic Spring (1904) by D.W. Higgins". Gaslight.mtroyal.ab.ca. http://gaslight.mtroyal.ab.ca/gaslight/mysticXN.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ Will and Ariel Durant (1950), The Age of Faith, p. 573.

- ↑ Lynn, p. 255, 257.

- ↑ http://www.classicalfencing.com/articles/Angelo.php accessed 7/25/2009

- ↑ http://pages.sbcglobal.net/blyle/Angelo/46.png accessed 7/25/2009

- ↑ The Dishonor of Dueling, Ariel A. Roth

- ↑ "Mark Twain, A Biography by Albert Bigelow Paine: Part I A Comstock Duel". Classicauthors.net. http://www.classicauthors.net/Paine/twainbio/twainbio46.html. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ "Chapters from my Autobiography by Mark Twain: Chapter VIII". Twain.classicauthors.net. http://twain.classicauthors.net/autobiography/autobiography8.html. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ "The common is steeped in history, at Keep Englefield Green - The Heritage". Keepenglefieldgreen.org. http://keepenglefieldgreen.org/page12.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 "Smithsonian Magazine". Smithsonianmag.com. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/duel.html. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ Isaac Asimov, Treasury of Humor, page 202.

- ↑ "Sunan Abu Dawud: Book 14, Number 2659". Usc.edu. http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/fundamentals/hadithsunnah/abudawud/014.sat.html#014.2659. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ Not Just Another John Smith, usnews.com, January 21, 2007

- ↑ Drummond, William (1619). Heads of a conversation betwixt the famous poet Ben Johnson and William Drummond of Hawthornden, January 1619. http://books.google.com/books?id=ubHPBcMk2OMC&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22William+Drummond%22+jonson&as_brr=3&ei=S0PASPT7GY-2iwGjjPTsDQ&client=firefox-a#PPA43,M1.

- ↑ Thomas W. Gallant. "| Honor, Masculinity, and Ritual Knife Fighting in Nineteenth-Century Greece | The American Historical Review, 105.2". The History Cooperative. http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/ahr/105.2/ah000359.html. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ Hamilton, Joseph (1829). The only approved guide through all the stages of a quarrel ((Internet Archive) ed.). Dublin: Millikin. http://www.archive.org/details/onlyapprovedguid00hami. Retrieved 29/June/2009.

- ↑ Wilson Lyde, John (1838 (reprint 2004)). "Appendix". The Code of Honor, Or, Rules for the Government of Principals and Seconds in Duelling. reprinted by Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 9781419157042. http://books.google.com/books?id=VEIXLwMktEUC&q=Clonmell&dq=The+Code+of+Honor,+Or,+Rules+for+the+Government+of+Principals+and+Seconds+in+Duelling&source=gbs_keywords_r#search_anchor.

- ↑ Gwynn, Denis (1947). Daniel O'Connell. Cork University Press. p. 126. http://books.google.com/books?id=hR4qAAAAYAAJ&dq=%22daniel+o%27connell%22+%22+white+glove%22&q=+%22+white+glove%22&pgis=1#search_anchor.

- ↑ Dickens, Charles; Chapman and Hall, (May 10, 1862). All the year round. Dickens & Evans (Firm). pp. 212–216. http://books.google.com/books?id=KdUNAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA213&dq=%22crow+ryan%22.

- ↑ Marek Adamiec. "Polski kodeks honorowy". Monika.univ.gda.pl. http://monika.univ.gda.pl/~literat/honor/. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ V.Durasov "The Dueling Code" ISBN - 5-7905-1634-3, 5-94532-010-2

- ↑ (Russian)Pushkin duels. Full list

- ↑ Lynn, p. 257.

- ↑ Friday, Apr. 28, 1967 (1967-04-28). "Time Magazine". Time.com. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,843669,00.html?iid=chix-sphere. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ "Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, s. 71". http://www.canlii.org/en/ca/laws/stat/rsc-1985-c-c-46/latest/rsc-1985-c-c-46.html#71.. Retrieved 2009-11-27.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 A.R.S. 26-1114

- ↑ Conn. Gen. Stat. 27-251

- ↑ O.C.G.A. 38-2-546

- ↑ H.R.S. 124A-147

- ↑ Iowa Code 29B.108

- ↑ K.S.A. 48-3036

- ↑ 40.385, R.S.Mo.

- ↑ N.Y. Mil. Law 130.108

- ↑ O.R.C. Ann. 5924.114

- ↑ O.R.S. 398.393

- ↑ 51 Pa.C.S. 6036

- ↑ Rev. Code Wash. 38.38.768

- ↑ David S. Parker. "DAVID S. PARKER | Law, Honor, and Impunity in Spanish America: The Debate over Dueling, 18701920 | Law and History Review, 19.2". The History Cooperative. http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/lhr/19.2/parker.html. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ "Sinaloenses se retan a muerte como en Viejo Oeste - El Universal - Los Estados". El Universal. http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/notas/589707.html. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ "Where There's Life, There's Lawsuits ... - Google Books". Books.google.com. http://books.google.com/books?id=BkcMEKm_XUYC&pg=PA16&lpg=PA16&dq=uruguay+duel&source=web&ots=0lqW5UYw5z&sig=i771QHDINFKfLXJQw_Sgy3UhSY4#PPA16,M1. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ "Americas | 'Insulted' politician wants a pistol duel". BBC News. 2002-09-26. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/2283040.stm. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ Nick Caistor (5 May 2000). "Raúl Rettig (obituary)". The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/2000/may/05/guardianobituaries.chile.

- ↑ "The duel (U.S. title: The point of honor) (1908) by Joseph Conrad". Gaslight.mtroyal.ca. http://gaslight.mtroyal.ca/theduel.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

Sources

- Baldick, Robert. The Duel: A History of Duelling. London: Chapman & Hall, 1965.

- Bell, Richard, “The Double Guilt of Dueling: The Stain of Suicide in Anti-dueling Rhetoric in the Early Republic,” Journal of the Early Republic, 29 (Fall 2009), 383–410.

- Cramer, Clayton. Concealed Weapon Laws of the Early Republic: Dueling, Southern Violence, and Moral Reform

- Freeman, Joanne B. Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001; paperback ed., 2002)

- Freeman, Joanne B. "Dueling as Politics: Reinterpreting the Burr-Hamilton Duel." The William and Mary Quarterly, 3d series, 53 (April 1996): 289–318.

- Frevert, Ute. "Men of Honour: A Social and Cultural History of the Duel." trans. Anthony Williams Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995.

- Greenberg, Kenneth S. "The Nose, the Lie, and the Duel in the Antebellum South." American Historical Review 95 (February 1990): 57–73.

- James Kelly. That Damn'd Thing Called Honour: Duelling in Ireland 1570–1860" (1995)

- Kevin McAleer. Dueling: The Cult of Honor in Fin-de-Siecle Germany (1994)

- Morgan, Cecilia. "'In Search of the Phantom Misnamed Honour': Duelling in Upper Canada." Canadian Historical Review 1995 76(4): 529–562.

- Rorabaugh, W. J. "The Political Duel in the Early Republic: Burr v. Hamilton." Journal of the Early Republic 15 (Spring 1995): 1–23.

- Schwartz, Warren F., Keith Baxter and David Ryan. "The Duel: Can these Gentlemen be Acting Efficiently?." The Journal of Legal Studies 13 (June 1984): 321–355.

- Steward, Dick. Duels and the Roots of Violence in Missouri (2000),

- Williams, Jack K. Dueling in the Old South: Vignettes of Social History (1980) (1999),

- Wyatt-Brown, Bertram. Honor and Violence in the Old South (1986)

- Wyatt-Brown, Bertram. Southern Honor: Ethics and Behavior in the Old South (1982),

Popular works

- The Code of Honor; or, Rules for the Government of Principals and Seconds in Duelling, John Lyde Wilson 1838

- The Field of Honor Benjamin C. Truman. (1884); reissued as Duelling in America (1993).

- Savannah Duels & Duellists, Thomas Gamble (1923)

- Gentlemen, Swords and Pistols, Harnett C. Kane (1951)

- Pistols at Ten Paces: The Story of the Code of Honor in America, William Oliver Stevens (1940)

- The Duel: A History, Robert Baldick (1965, 1996)

- Dueling With the Sword and Pistol: 400 Years of One-on-One Combat, Paul Kirchner (2004)

- Duel, James Landale (2005). ISBN 1-84195-647-3. The story of the last fatal duel in Scotland

- Ritualized Violence Russian Style: The Duel in Russian Culture and Literature, Irina Reyfman (1999).

External links

- Ahn, Tom, Sandford, Jeremy, and Paul Shea. 2010. "Mend it, Don't End it: Optimal Mortality in Affairs of Honor" mimeo

- Allen, Douglas, W., and Reed, Clyde, G., 2006, "The Duel of Honor: Screening for Unobservable Social Capital," American Law and Economics Review: 1–35.

- "Duels and Dueling on the Web", "...a comprehensive guide and web directory to pistol and sword duelling in history, literature and film..."

- Kingston, Christopher G., and Wright, Robert E. "The Deadliest of Games: The Institution of Deuling" Dept. of Econ, Amherst College, Stern School of Business, NY Univ.