Druze

Druze star |

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 750,000 to 2,500,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 520,000[1][2] | |

| 211,200[3] | |

| 102,000[4][2] | |

| 20,000[5] | |

| Outside the Middle East | 100,000 |

| 20,000[6] | |

| 3,000[7] | |

| Religions | |

| Unitarian Druze | |

| Scriptures | |

| Rasa'il al-hikmah (Epistles of Wisdom) | |

| Languages | |

| Arabic English Hebrew (in Israel) French (in Lebanon and Syria) |

|

| Part of a series on Shī‘ah Islam |

| Ismāʿīlism |

|---|

|

| Concepts |

| The Qur'ān · The Ginans Reincarnation · Panentheism Imām · Pir · Dā‘ī l-Muṭlaq ‘Aql · Numerology · Taqiyya Żāhir · Bāṭin |

| Seven Pillars |

| Guardianship · Prayer · Charity Fasting · Pilgrimage · Struggle Purity · Profession of Faith |

| History |

| Shoaib · Nabi Shu'ayb Seveners · Qarmatians Fatimids · Baghdad Manifesto Hafizi · Taiyabi Hassan-i Sabbah · Alamut Sinan · Hashshashīn Pir Sadardin · Satpanth Aga Khan · Jama'at Khana Huraat-ul-Malika · Böszörmény |

| Early Imams |

| Ali · Ḥassan · Ḥusain as-Sajjad · al-Baqir · aṣ-Ṣādiq Ismā‘īl · Muḥammad Abdullah /Wafi Ahmed / at-Taqī Husain/ az-Zakī/Rabi · al-Mahdī al-Qā'im · al-Manṣūr al-Mu‘izz · al-‘Azīz · al-Ḥākim az-Zāhir · al-Mustansir · Nizār al-Musta′lī · al-Amīr · al-Qāṣim |

| Groups and Present leaders |

| Nizārī · Aga Khan IV Druze · Mowafak_Tarif Dawūdī · Burhanuddin Sulaimanī · Al-Fakhri Abdullah Alavī · Ṭayyib Ziyā'u d-Dīn Atba-i-Malak Badra · Amiruddin Atba-i-Malak Vakil · Razzak Hebtiahs |

The Druze (Arabic: درزي, derzī or durzī, plural دروز, durūz, Hebrew: דרוזים druzim) are a religious community found primarily in Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan, whose traditional religion is said to have begun as an offshoot of Islam, but is unique in its incorporation of Gnosticism, Neoplatonism and other philosophies, similar to other followers of Ismaili Shi'a Islam.[8]

Theologically, Druze consider themselves "an Islamic Unist, reformatory sect".[9][10] The Druze call themselves Ahl al-Tawhid "People of Unitarianism or Monotheism" or al-Muwaḥḥidūn "Unitarians, Monotheists."

Contents |

Location

The Druze people reside primarily in Syria, Lebanon, and Israel.[11] The Israeli Druze are mostly in Galilee (81%) and around Haifa (19%).[4] The Jordanian Druze can be found in Amman and Zarka; about 50% live in the town of Azraq, and a smaller number in Irbid and Aqaba. The Golan Heights, the mountainous region in the south of Syria, is home to about 20,000 Druze.[2] The Institute of Druze Studies estimates that 40%–50% of Druze live in Syria, 30%–40% in Lebanon, 6%–7% in Israel, and 1%–2% in Jordan.[12][13]

Large communities of expatriate Druze also live outside the Middle East in Australia, Canada, Europe, Latin America, the United States and West Africa. They use the Arabic language and follow a social pattern very similar to the other East Mediterraneans of the region.[14]

There are thought to be as many as 1 million Druze worldwide, the vast majority in the Levant or East Mediterranean.[15]

History

Origin of the name

The most plausible theory of the origin of the name Druze is that it derived from the name of Anushtakīn ad-Darazī, one of the early leaders of the faith. However, the Druze consider ad-Darazī a heretic[16] who practiced ghuluww (Arabic, "exaggeration"), which refers to the belief that God was incarnated in human beings, especially ‘Ali and his descendants. Ad-Darazī was a dā‘ī ("missionary") who first preached an unorthodox version of the faith to outsiders in 1016. He claimed to be the true leader of the faithful rather than Hamza ibn ‘Ali (the appointed leader) and also that al-Hakim and his ancestors were incarnations of God.

Although he is considered a renegade by the Unitarian community, the name "Druze" is still used for identification and for historical reasons. Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah executed ad-Darazi in 1018 for his teachings.[9][16]

Some authorities see in the name "Druze" a descriptive epithet, derived from Arabic dâresah ("those who study").[17] Others have speculated that the word comes from the Arabic-Persian word Darazo (درز "bliss") or from Shaykh Hussayn ad-Darazī, who was one of the early converts to the faith.[18] In the early stages of the movement, the word "Druze" is rarely mentioned by historians, and in Druze religious texts only the word Muwaḥḥidūn ("Unitarian") appears. The only early Arab historian who mentions the Druze is the 11th century Christian scholar Yahyá ibn Sa‘īd al-Antākī, who clearly refers to the heretical group created by ad-Darazī rather than the followers of Hamza ibn ‘Alī.[18] As for Western sources, Benjamin of Tudela, the Jewish traveler who passed through Lebanon in or about 1165, was one of the first European writers to refer to the Druzes by name. The word Dogziyin ("Druzes") occurs in an early Hebrew edition of his travels, but it is clear that this is a scribal error. Be that as it may, he described the Druze as "mountain dwellers, monotheists, who believe in "soul eternity" and reincarnation."[19]

Early history

The Druze faith began as a movement in Ismailism that was mainly influenced by Greek philosophy and gnosticism and opposed certain religious and philosophical ideologies that were present during that epoch.

The faith was founded by Hamza ibn ‘Alī ibn Ahmad, a Persian Ismaili mystic and scholar. He came to Egypt in 1014 and assembled a group of scholars and leaders from across the Islamic world to form a new Unitarian movement. The order's meetings were held in the Raydan Mosque, near the Al-Hakim Mosque.[20]

In 1017, Hamza officially revealed the Druze faith and began to preach his doctrine. Hamza gained the support of the Fātimid Caliph al-Hakim, who issued a decree promoting religious freedom prior to the declaration of the divine call.

Remove ye the causes of fear and estrangement from yourselves. Do away with the corruption of delusion and conformity. Be ye certain that the Prince of Believers hath given unto you free will, and hath spared you the trouble of disguising and concealing your true beliefs, so that when ye work ye may keep your deeds pure for God. He hath done thus so that when you relinquish your previous beliefs and doctrines ye shall not indeed lean on such causes of impediments and pretensions. By conveying to you the reality of his intention, the Prince of Believers hath spared you any excuse for doing so. He hath urged you to declare your belief openly. Ye are now safe from any hand which may bringeth harm unto you. Ye now may find rest in his assurance ye shall not be wronged. Let those who are present convey this message unto the absent so that it may be known by both the distinguished and the common people. It shall thus become a rule to mankind; and Divine Wisdom shall prevail for all the days to come.[21]

Al-Hakim became a central figure in the Druze faith even though his own religious position was disputed among scholars. John Esposito states that al-Hakim believed that "he was not only the divinely appointed religio-political leader but also the cosmic intellect linking God with creation."[22], while others like Nissim Dana and Mordechai Nisan state that he is perceived as the manifestation and the reincarnation of God or presumably the image of God.[23][24]

Some Druze and non-Druze scholars like Samy Swayd and Sami Makarem state that this confusion is due to confusion about the role of the early heretical preacher ad-Darazi, whose teachings the Druze rejected as heretical.[25] These sources assert that al-Hakim refused ad-Darazi's claims of divinity,[9][26][27] and ordered the elimination of his movement while supporting that of Hamza ibn Ali.[28]

Al-Hakim disappeared one night while out on his evening ride - presumably assassinated, perhaps at the behest of his formidable elder sister Sitt al-Mulk. The Druze believe he went into Occultation with Hamza ibn Ali and three other prominent preachers, leaving the care of the "Unitarian missionary movement" to a new leader, Bahā'u d-Dīn.

Persecution during the Fatimid times

Al-Hakim was replaced by his underage son, ‘Alī az-Zahir. The sect founded by Hamzah ibn ‘Alī, which was prominent in the Levant, North Africa, Egypt, Arabia, Iraq, Persia, Yemen, and other parts of the Near East, acknowledged az-Zahir as the Caliph but followed Hamzah as its Imam.[9] The young Caliph's regent, Sitt al-Mulk, ordered the army to destroy the movement in 1021.[16] At the same time, Bahā' ad-Dīn as-Samuki assumed leadership of the Druze.[9]

The killing ranged from Antioch to Alexandria, where tens of thousands of Druze were slaughtered by the Fatimid army.[16] The largest massacre was at Antioch, where 5000 Druze religious leaders were killed, followed by that of Aleppo.[16] The massacres are well described in the remaining scriptures written by as-Samuki, which recorded how the Fatimid army brutally put to death infants, women, and men.[16]

The closing of the faith

Az-Zahir finally agreed to leave the Druze alone in 1026 — notably, three years after Sitt al-Mulk's death — and as-Samuki sent feelers and missionaries deeper into the Levant.

After two decades of building strong new communities in the Levant, as-Samuki declared that the sect would no longer accept new pledges in 1043, and since that time proselytization has been prohibited.[9]

During the Crusades

It was during the period of Crusader rule in Syria (1099–1291) that the Druze first emerged into the full light of history in the Gharb region of the Chouf Mountains. As powerful warriors serving the Muslim rulers of Damascus against the foreign invaders, the Druze were given the task of keeping watch over the Crusaders in the seaport of Beirut, with the aim of preventing them from making any encroachments inland. Subsequently, the Druze chiefs of the Gharb placed their considerable military experience at the disposal of the Mamluk rulers of Egypt (1250–1516); first, to assist them in putting an end to what remained of Crusader rule in coastal Syria, and later to help them safeguard the Syrian coast against Crusader retaliation by sea.[29]

In the early period of the Crusader era, the Druze feudal power was in the hands of two families, the Tanukhs and the Arslans. From their fortresses in the Gharb district (modern Aley Province) of southern Mount Lebanon, the Tanukhs led their incursions into the Phoenician coast and finally succeeded in holding Beirut and the marine plain against the Franks. Because of their fierce battles with the crusaders, the Druzes earned the respect of the Sunni Muslim Caliphs and thus gained important political powers. After the middle of the twelfth century, the Ma’an family superseded the Tanukhs in Druze leadership. The origin of the family goes back to a Prince Ma’an who made his appearance in the Lebanon in the days of the ‘Abbasid Caliph al-Mustarshid (1118 AD-1135 AD). The Ma’ans chose for their abode the Chouf district in the southern part of Western Lebanon, overlooking the maritime plain between Beirut and Sidon, and made their headquarters in Baaqlin, which is still a leading Druze village. They were invested with feudal authority by Sultan Nur-al-Dīn and furnished respectable contingents to the Muslim ranks in their struggle against the Crusaders.[30]

Persecution during the Mamluk and Ottoman period

Having cleared Syria of the Franks, the Mamluk Sultans of Egypt turned their attention to the schismatic Muslims of Syria. In 1305, after the issuing of a fatwa by the Hanbali Sunni scholar Ibn Taymiyyah calling for jihad against the Druze, Alawites, Ismaili, and twelver Shiites, al-Malik al-Nasir inflicted a disastrous defeat on the Druze at Keserwan and forced outward compliance on their part to orthodox Sunni Islam. Later, under the Ottoman Turks, they were severely attacked at Ayn-Ṣawfar in 1585 after the Ottomans claimed that they assaulted their caravans near Tripoli.[30]

Consequently, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were to witness a succession of armed Druze rebellions against the Ottomans, countered by repeated Ottoman punitive expeditions against the Chouf, in which the Druze population of the area was severely depleted and many villages destroyed. These military measures, severe as they were, did not succeed in reducing the local Druze to the required degree of subordination. This led the Ottoman government to agree to an arrangement whereby the different nahiyes (districts) of the Chouf would be granted in iltizam ("fiscal concession") to one of the region's amirs, or leading chiefs, leaving the maintenance of law and order and the collection of its taxes in the area in the hands of the appointed amir. This arrangement was to provide the cornerstone for the privileged status which ultimately came to be enjoyed by the whole of Mount Lebanon in Ottoman Syria, Druze and Christian areas alike.[31]

Ma’an dynasty

With the advent of the Ottoman Turks and the conquest of Syria by Sultan Selim I in 1516, the Ma’ans were acknowledged by the new rulers as the feudal lords of southern Lebanon. Druze villages spread and prospered in that region, which under Ma’an leadership so flourished that it acquired the generic term of Jabal Bayt-Ma’an (the mountain of the Ma’an family) or Jabal al-Druze. The latter title has since been usurped by the Hawran region, which since the middle of the nineteenth century has proven a haven of refuge to Druze emigrants from Lebanon and has become the headquarters of Druze power.[30]

Under Fakhreddin II, the Druze dominion increased until it included almost all Syria, extending from the edge of the Antioch plain in the north to Safad in the south, with a part of the Syrian desert dominated by Fakhreddin's castle at Tadmur (Palmyra), the ancient capital of Zenobia. The ruins of this castle still stand on a steep hill overlooking the town. Fakhr-al-Dīn became too strong for his Turkish sovereign in Constantinople. He went so far in 1608 as to sign a commercial treaty with Duke Ferdinand I of Tuscany containing secret military clauses. The Sultan then sent a force against him, and he was compelled to flee the land and seek refuge in the courts of Tuscany and Naples in 1614.

In 1618 political changes in the Ottoman sultanate had resulted in the removal of many enemies of Fakhr-al-Din from power, signaling the prince's triumphant return to Lebanon soon afterwards.

In 1632 Ahmad Koujak was named Lord of Damascus. Koujak was a rival of Fakhr-al-Din and a friend of the sultan Murad IV, who ordered Koujak and the sultanat navy to attack Lebanon and depose Fakhr-El-Din.

This time the prince decided to remain in Lebanon and resist the offensive, but the death of his son Ali in Wadi el-Taym was the beginning of his defeat. He later took refuge in Jezzine's grotto, closely followed by Koujak who eventually caught up with him and his family.

Fakhr-al-Din finally traveled to Turkey, appearing before the sultan, defending himself so skillfully that the sultan gave him permission to return to Lebanon.

Later, however, the sultan changed his orders and had Fakhr-al-Din and his family killed on 13 April 1635 in Istanbul, the capital city of the Ottoman Empire, bringing an end to an era in the history of Lebanon, a country which would not regain its current boundaries, which Fakhr-al-Din once ruled, until Lebanon was proclaimed a republic in 1920.

Fakhr-al-Din was the first ruler in modern Lebanon to open the doors of his country to foreign Western influences. Under his auspices the French established a khān (hostel) in Sidon, the Florentines a consulate, and Christian missionaries were admitted into the country. Beirut and Sidon, which Fakhr-al-Dīn beautified, still bear traces of his benign rule.

Shihab Dynasty

As early as the days of Saladin, and while the Ma’ans were still in complete control over southern Lebanon, the Shihab tribe, originally Hijaz Arabs but later settled in Ḥawran, advanced from Ḥawran, in 1172, and settled in Wadi-al-Taym at the foot of Mt. Hermon. They soon made an alliance with the Ma’ans and were acknowledged as the Druze chiefs in Wadi-al-Taym. At the end of the seventeenth century (1697) the Shihabs succeeded the Ma’ans in the feudal leadership of Druze southern Lebanon, although they professed Sunni Islam. Secretly, they showed sympathy with Druzism, the religion of the majority of their subjects.

The Shihab leadership continued until the middle of the 19th century and culminated in the illustrious governorship of Amir Bashir Shihab II (1788–1840) who, after Fakhr-al-Din, was the most powerful feudal lord Lebanon produced. Though governor of the Druze Mountain Bashir was a crypto-Christian, and it was he whose aid Napoleon solicited in 1799 during his campaign against Syria.

Having consolidated his conquests in Syria (1831–1838), Ibrahim Pasha, son of the viceroy of Egypt, Muhammad Ali Pasha, made the fatal mistake of trying to disarm the Christians and Druzes of the Lebanon and to draft the latter into his army. This was contrary to the principles of the life of independence which these mountaineers had always lived, and resulted in a general uprising against Egyptian rule. The uprising was encouraged, for political reasons, by the British. The Druzes of Wadi-al-Taym and Ḥawran, under the leadership of Shibli al-Aryan, distinguished themselves in their stubborn resistance at their inaccessible headquarters, al-Laja, lying southeast of Damascus.[30]

Qaysites and the Yemenites

The conquest of Syria by the Muslim Arabs in the middle of the seventh century introduced into the land two political factions later called the Qaysites and the Yemenites. The Qaysite party represented the Ḥijaz and Bedouin Arabs who were regarded as inferior by the Yemenites who were earlier and more cultured emigrants into Syria from southern Arabia. Druzes and Christians grouped in political rather than religious parties so the party lines in Lebanon obliterated racial and religious lines and the people grouped themselves regardless of their religious affiliations, into one or the other of these two parties. The sanguinary feuds between these two factions depleted, in course of time, the manhood of the Lebanon and ended in the decisive battle of Ain Dara in 1711, which resulted in the utter defeat of the Yemenite party. Many Yemenite Druzes thereupon immigrated to the Hawran region and thus laid the foundation of Druze power there.[30]

Civil War of 1860

The Druzes and their Christian Maronite neighbors, who had thus far lived as religious communities on friendly terms, entered a period of social disturbance in the year 1840, which culminated in the civil war of 1860. For this disturbance the Ottoman Sultan was, in a great measure, responsible. The Sultan, realizing that the only way to bring the semi-independent people of Lebanon under his direct control was to sow the seeds of discord among the people themselves, inaugurated in the mountain a policy long tried and found successful in the Ottoman provinces, the policy of "divide and rule".[30]

Also, after the Shehab dynasty converted to Christianity, the Druze community and feudal leaders came under attack from the regime with the collaboration of the Catholic Church, and the Druze lost most of their political and feudal powers. Also, the Druze formed a strong ally with Britain and allowed Protestant missionaries to enter Mount Lebanon, creating tension between them and the Catholic Maronites, who were supported by the French.

The Maronite-Druze conflict in 1840-60 was an outgrowth of the Maronite Christian independence movement directed against the Druze and Ottoman-Turks. The civil war was not therefore a religious war, except in Damascus where it spread and where the population was anti-Christian. The movement culminated with the 1859-60 massacre and defeat of the Christians by the Druzes, who were aided by the Turks. The civil war of 1860 cost the Christians some ten thousand lives in Damascus, Zahle, Deir al-Qamar, Hasbaya and other towns of Lebanon.

The European powers then determined to intervene and authorized the landing in Beirut of a body of French troops under General Beaufort d’Hautpoul, whose inscription can still be seen on the historic rock at the mouth of Nahr al-Kalb. French intervention on behalf of the Maronites did not help the Maronite national movement since France was restricted in 1860 by Britain which did not want the Ottoman Empire dismembered. But European intervention pressured the Turks to treat the Maronites more justly.[32] Following the recommendations of the powers, the Ottoman Porte granted Lebanon local autonomy, guaranteed by the powers, under a Christian governor. This autonomy was maintained until World War I.[30][33]

Modern history

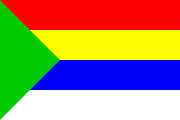

In Lebanon, Syria, and Israel, the Druze have official recognition as a separate religious community with its own religious court system. Their symbol is an array of five colors: green, red, yellow, blue, and white. Each color pertains to a symbol defining its principles: green for Aql "the Universal Mind", red for Nafs "the Universal Soul", yellow for Kalima "the Truth/Word", blue for Sabq "the Potentiality/Cause", and white for Talī "the Actuality/Effect". These principles are why the number five has special considerations among the religious community; it is usually represented symbolically by a five-pointed star.

In Syria

In Syria, most Druze live in the Jebel al-Druze, a rugged and mountainous region in the southwest of the country, which is more than 90 percent Druze inhabited; some 120 villages are exclusively so.

The Druze always played a far more important role in Syrian politics than its comparatively small population would suggest. With a community of little more than 100,000 in 1949, or roughly three percent of the Syrian population, the Druze of Syria's southeastern mountains constituted a potent force in Syrian politics and played a leading role in the nationalist struggle against the French. Under the military leadership of Sultan Pasha al-Atrash, the Druze provided much of the military force behind the Syrian Revolution of 1925-1927. In 1945, Amir Hasan al-Atrash, the paramount political leader of the Jebel al-Druze, led the Druze military units in a successful revolt against the French, making the Jebel al-Druze the first and only region in Syria to liberate itself from French rule without British assistance. No Syrians played a more heroic role in the struggle against colonialism or shed more blood for independence than the Druze. At independence the Druze, made confident by their successes, expected that Damascus would reward them for their many sacrifices on the battlefield. They demanded to keep their autonomous administration and many political privileges accorded them by the French and sought generous economic assistance from the newly independent government.

Well-led by the Atrash household and jealous of their reputation as Arab nationalists and proud warriors, the Druze leaders refused to be beaten into submission by Damascus or cowed by threats. When a local paper in 1945 reported that President Shukri al-Quwatli (1943–1949) had called the Druzes a "dangerous minority", Sultan Pasha al-Atrash flew into a rage and demanded a public retraction. If it were not forthcoming, he announced, the Druzes would indeed become "dangerous" and a force of 4,000 Druze warriors would "occupy the city of Damascus." Quwwatli could not dismiss Sultan Pasha's threat. The military balance of power in Syria was tilted in favor of the Druzes, at least until the military build up during the 1948 War in Palestine. One advisor to the Syrian Defense Department warned in 1946 that the Syrian army was "useless", and that the Druzes could "take Damascus and capture the present leaders in a breeze."

During the four years of Adib Shishakli's rule in Syria (December 1949 to February 1954) (in August 25, 1952: Adib al-Shishakli created the Arab Liberation Movement (ALM), a progressive party with pan-Arabist and socialist views . [34]), the Druze community was subjected to a heavy attack by the Syrian regime. Shishakli believed that among his many opponents in Syria, the Druzes were the most potentially dangerous, and he was determined to crush them. He frequently proclaimed: "My enemies are like a serpent: the head is the Jebel al-Druze, the stomach Hims, and the tail Aleppo. If I crush the head the serpent will die." Shishakli dispatched 10,000 regular troops to occupy the Jebel al-Druze. Several towns were bombarded with heavy weapons, killing scores of civilians and destroying many houses. According to Druze accounts, Shishakli encouraged neighboring bedouin tribes to plunder the defenseless population and allowed his own troops to run amok.

Shishakli launched a brutal campaign to defame the Druzes for their religion and politics. He accused the entire community of treason, at times claiming they were agents of the British and Hashimites, at others that they were fighting for Israel against the Arabs. He even produced a cache of Israeli weapons allegedly discovered in the Jabal. Even more painful for the Druze community was his publication of "falsified Druze religious texts" and false testimonials ascribed to leading Druze sheikhs designed to stir up sectarian hatred. This propaganda was also broadcast in the Arab world, mainly Egypt. Shishakli was assassinated in Brazil on September 27, 1964 by a Druze seeking revenge for Shishakli's bombardment of the Jebel al-Druze.

He forcibly integrated minorities into the national Syrian social structure, his "Syrianization" of Alawite and Druze territories had to be accomplished in part using violence, he declared: "My enemies are like serpent. The head is the Jabal Druze, If I crush the head the serpent will die" (Seale 1963:132). To this end, al-Shishakli encouraged the stigmatization of minorities. He saw minority demands as tantamount to treason. His increasingly chauvinistic notions of Arab nationalism were predicated on the denial that "minorities" existed in Syria. [35]

After the Shishakli's military campaign, the Druze community lost a lot of its political influence, but many Druze military officers played an important role when it comes to the Baathist regime currently ruling Syria.[36]

In Lebanon

The Druze community played an important role in the formation of the modern state of Lebanon, and even though they are a minority they played an important role in the Lebanese political scene. Before and during the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990), the Druze were in favor of Pan-Arabism and Palestinian resistance represented by the PLO. Most of the community supported the Progressive Socialist Party formed by the Lebanese leader Kamal Jumblatt and they fought alongside other leftist and Palestinian parties against the Lebanese Front that was mainly constituted of Christians. After the assassination of Kamal Jumblatt on March 16, 1977, his son Walid Jumblatt took the leadership of the party and played an important role in preserving his father's legacy and sustained the existence of the Druze community during the sectarian bloodshed that lasted until 1990.

In August 2001, Patriarch Nasrallah Boutros Sfeir toured the predominantly Druze Chouf region of Mount Lebanon and visited Mukhtara, the ancestral stronghold of Druze leader Walid Jumblatt. The tumultuous reception that Sfeir received not only signified a historic reconciliation between Maronites and Druze, who fought a bloody war in 1983-1984, but underscored the fact that the banner of Lebanese sovereignty had broad multi-confessional appeal[37] and was a cornerstone for the Cedar Revolution. The second largest political party supported by Druze is the Lebanese Democratic Party led by Prince Talal Arslan the son of one of the independence leaders Prince Magid Arslan. Also political parties such as the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, Lebanese Unification Movement and Lebanese Communist Party have a considerable amount of supporters in the community.

In Israel

In Israel, the majority of the approximately 102,000 Druze consider themselves a distinct religious group.[38] Since 1957, the Israeli government has also designated the Druze a distinct ethnic community, at the request of the community's leaders.

The Druze culture is Arab and their language Arabic but they opted against mainstream Arab nationalism in 1948 and have since served (first as volunteers, later within the draft system) in the Israel Defense Forces and the Border Police. They are located in the north of the country, mainly on hilltops; historically as a defense against attack and persecution. [39], which they were subject to historically from the Arab-Muslims [40]. The Druze mostly do not identify with the cause of Arab nationalism. In the years preceding the founding of the State of Israel, Arab nationalists persecuted the Druze. [41]

Until his death in 1993, the Druze community in Israel was led by Shaykh Amin Tarif, a charismatic figure regarded by many within the Druze community internationally as the preeminent religious leader of his time.[42]

Israeli Druze Patriotism

Druze citizens are prominent in the Israel Defense Forces and in politics. A considerable number of Israeli Druze soldiers have fallen in Israel's wars since the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. The bond between Jewish and Druze soldiers is commonly known by the term "a covenant of blood" (Hebrew: ברית דמים, brit damim), although in recent years the phrase has been criticized as the Israeli government has been accused for failing to open up employment opportunities to Druze youth outside of the army.[43] Five Druze lawmakers currently have been elected to serve in the 18th Knesset, a disproportionately large number considering their population.[44] Reda Mansour a Druze poet, historian and diplomat, explained: “We are the only non-Jewish minority that is drafted into the military, and we have an even higher percentage in the combat units and as officers than the Jewish members themselves. So we are considered a very nationalistic, patriotic community.”[45]

The chairman of the forum of the Druze and Circassian authority heads, and head of the Kasra Adia municipality, Nabiah Nasser A-Din, criticized the "multi-cultural" Israeli constitution proposed by the Israeli Arab organization Adalah, saying that he finds it unacceptable. "The state of Israel is Jewish state as well as a democratic state that espouses equality and elections. We invalidate and reject everything that the Adalah organization is requesting," he said. According to A-din, the fate of Druze and Circassians in Israel is intertwined with that of the state. "This is a blood pact, and a pact of the living. We are unwilling to support a substantial alteration to the nature of this state, to which we tied our destinies prior to its establishment," he said.[46]

Support for the spread of the Seven Noahide Commandments

In January 2004, the spiritual leader of the Druze community in Israel, Shaykh Mowafak Tarif, signed a declaration calling on all non-Jews in Israel to observe the Seven Noahide Laws as laid down in the Bible and expounded upon in Jewish tradition. The mayor of the Galilean city of Shefa-'Amr also signed the document.[47] The declaration includes the commitment to make a "...better humane world based on the Seven Noahide Commandments and the values they represent commanded by the Creator to all mankind through Moses on Mount Sinai."[47]

Support for the spread of the Seven Noahide Commandments by the Druze leaders reflects the biblical narrative itself. The Druze community reveres the non-Jewish father-in-law of Moses, Jethro, whom some Muslims identify with Shuʻayb. According to the biblical narrative, Jethro joined and assisted the Jewish people in the desert during the Exodus, accepted monotheism, but ultimately rejoined his own people. The tomb of Jethro near Tiberias is the most important religious site for the Druze community.[47] It has been claimed that the Druze are actually descendants of Jethro.

Druze of the Golan Heights

In the late 1970s, the Israeli government offered all non-Israelis living in the Golan citizenship, which would entitle them to an Israeli driver's license and enable them to travel freely in Israel. In March 1981, the Druze community leaders imposed a socio-religious ban on Israeli citizenship and in November, a general strike was called that lasted five months and demonstrations were held that sometimes became violent. The Israeli authorities arrested the protest leaders and imposed curfews. On April 1, 1982, a 24-hour curfew was imposed during which soldiers confiscated the old ID cards and replaced them with new ones, signifying Israeli citizenship. This action caused an international outcry including two condemnatory UN resolutions.[48][49] Israel eventually relented and permitted retention of Syrian citizenship.

Today, fewer than 10% of the Druze of the Golan Heights are Israeli citizens; the remainder hold Syrian citizenship.[50] A factor in reluctance to accept Israeli citizenship may reflect fear of ill treatment or displacement by Syrian authorities should the Golan Heights eventually return to Syria.[51] By expressing pro-Syrian rhetoric and shunning Israel, Golan Druze feel they may be potentially rewarded by Syria, while simultaneously risking nothing in Israel's freewheeling society.[52] Although most of them identify themselves as Syrian and generally ostracise those who have accepted an Israeli laissez-passer,[53] they nevertheless feel alienated from the autocratic regime in Damascus and fear a return to Syria. According to the Associated Press, "many young Druse have been quietly relieved at the failure of previous Syrian-Israeli peace talks to go forward" and "many have come to appreciate aspects of Israel's liberal democratic society, although few risk saying so publicly for fear of Syrian retribution."[54] Most Druze in the heights live relatively comfortable lives in a freer society than they would have in Syria under the present regime[55] and their standard of living vastly surpasses that of their counterparts on the Syrian side of the border.[56] Some optimists see the future Golan as a sort of Hong Kong, continuing to enjoy the perks of Israel’s dynamic economy and open society, while coming back under the sovereignty of a stricter, less developed Syria[52] The Druze are also reportedly well-educated and relatively prosperous, and have made use of Israel's universities.

Druze in the Golan are not drafted into the Israeli army (although a minority serve voluntarily) and many travel to Syria regularly to visit family or receive university degrees in Damascus. A year after Israel annexed the Golan, on April 14, 1982, the Druze communities around Mt. Hermon launched a six-month non-violent general strike in protest of Israel's annexation of the Golan.

As of April 2009 there were 21 Golan Druze in Israeli prisons for offenses such as attacks against IDF, Israeli police and Israeli settlements, supporting Palestinians during the Intifadas and attempted kidnapping of Israeli soldier.[57][58]

In the 2009 elections, 1,193 residents of Ghajar and 809 residents of the Druze villages were eligible voters, out of approximately 1,200 Ghajar residents and 12,600 Druze village residents who were of voting age.[59]

Both personal and business relations exist between the Druze and their Jewish neighbors; there is little tension between the two groups.[1] As a humanitarian gesture, since 2005, Israel allows Druze farmers to export some 11,000 tons of apples to Syria each year, the first kind of trade ever made between Syria and Israel. Since 1988, Israel has allowed Druze clerics to make annual religious pilgrimages to Syria.[54]

Beliefs of the Druze

The Druze are considered to be a social group as well as a religion, but not a distinct ethnic group. Also complicating their identity is the custom of Taqiya—concealing or disguising their beliefs when necessary—that they adopted from Shia Islam and the esoteric nature of the faith, in which many teachings are kept secretive. Druze in different states can have radically different lifestyles. Some claim to be Muslim, some do not. The Druze faith is said to abide by Islamic principles, but they tend to be separatist in their treatment of Druze-hood, and their religion differs from mainstream Islam on a number of fundamental points.[1]

Druze does not allow conversion to the religion. Marriage between Druze and non-Druze is strongly discouraged for religious, political and historical reasons.

God in the Druze faith

The Druze conception of the deity is declared by them to be one of strict and uncompromising unity. The main Druze doctrine states that God is both transcendent and immanent, in which He is above all attributes but at the same time He is present.[60]

In their desire to maintain a rigid confession of unity, they stripped from God all attributes (tanzīh) which may lead to polytheism (shirk). In God, there are no attributes distinct from his essence. He is wise, mighty, and just, not by wisdom, might, and justice, but by his own essence. God is "the Whole of Existence", rather than "above existence" or on His throne, which would make Him "limited." There is neither "how", "when", nor "where" about him; he is incomprehensible.[61]

In this dogma, they are similar to the semi-philosophical, semi-religious body which flourished under Al-Ma'mun and was known by the name of Mu'tazila and the fraternal order of the Brethren of Purity (Ikhwan al-Ṣafa).[30]

But unlike the Mu’tazilla, and similar to some branches of Sufism, the Druze believe in the concept of Tajalli (meaning "theophany").[61] Tajalli, which is more often misunderstood by scholars and writers and is usually confused with the concept of incarnation,

...is the core spiritual beliefs [sic] in the Druze and some other intellectual and spiritual traditions.... In a mystical sense, it refers to the light of God experienced by certain mystics who have reached a high level of purity in their spiritual journey. Thus, God is perceived as the Lahut [the divine] who manifests His Light in the Station (Maqaam) of the Nasut [material realm] without the Nasut becoming Lahut. This is like one's image in the mirror: one is in the mirror but does not become the mirror. The Druze manuscripts are emphatic and warn against the belief that the Nasut is God.... Neglecting this warning, individual seekers, scholars, and other spectators have considered al-Hakim and other figures divine.

...In the Druze scriptural view, Tajalli 'takes a central stage.' One author comments that Tajalli occurs when the seeker's humanity is annihilated so that divine attributes and light are experienced by the person."[61]

The concept of God incarnating either as or in a human seems "to contradict with what the Druze scriptural view has to teach about the Oneness of God, while tajalli [sic] is at the center of the Druze and some other, often mystical, traditions."[61]

Scriptures

Esotericism

The Druze believe that many teachings given by Prophets, religious leaders, and Holy Books, had esoteric meanings preserved for those of intellect, in which some teachings are mere symbols and allegoristic in nature and for that they divide the understanding of holy books and teachings into three layers. These layers according to the Druze are:

- The obvious or exoteric (Zahir), accessible to anyone who can read or hear;

- The hidden or esoteric (Batin), accessible to those who are willing to search and learn through the concept of (exegesis); and

- The hidden of the hidden, a concept known as Anagoge, inaccessible to all but a few really enlightened individuals who truly understand the nature of the universe.[62]

Unlike some Islamic esoteric movements known as the batinids at that time, the Druzes don’t believe that the esoteric meaning abrogates or necessarily abolishes the exoteric one. For example, Hamza bin Ali, refutes such claims by stating that, if the esoteric interpretation of Taharah (purity), is the purity of the heart and soul, it doesn’t mean that a person can discard his physical purity, as Salah (prayer) is useless if a person is untruthful in his speech and for that the esoteric and exoteric meanings complement each other.[63]

Precepts of the Druze faith

The Druze follow seven precepts that are considered the core of the faith, and are perceived by them as the essence of the pillars of Islam. The Seven Druze precepts are:

- Veracity in speech and the truthfulness of the tongue.

- Protection and mutual aid to the brethren in faith.

- Renunciation of all forms of former worship (specifically, invalid creeds) and false belief.

- Repudiation of the devil (Iblis), and all forces of evil (translated from Arabic Toghyan meaning "despotism").

- Confession of God's unity.

- Acquiescence in God's acts no matter what they be.

- Absolute submission and resignation to God's divine will in both secret and public.[64]

ˤUqqāl and Juhhāl

The Druze are divided into two groups. The largely secular majority, called al-Juhhāl (جهال) ("the Ignorant") are not granted access to the Druze holy literature or allowed to attend the initiated Uqqal's religious meetings. They are around 80% of the Druze population and are not obliged to follow the ascetic traditions of the Uqqal .

The initiated religious group, which includes both men and women (about 20% of the population), is called al-ˤUqqāl (عقال), ("the Knowledgeable Initiates"). They have a special mode of dress designed to comply with Quranic traditions. Women can opt to wear al-mandīl, a loose white veil, especially in the presence of other people. They wear al-mandīl on their heads to cover their hair and wrap it around their mouths and sometimes over their noses as well. They wear black shirts and long skirts covering their legs to their ankles. Male ˤuqqāl grow mustaches, and wear dark Levantine/Turkish traditional dresses, called the shirwal, with white turbans that vary according to the Uqqal's hierarchy.

Al-ˤuqqāl have equal rights to al-Juhhāl, but establish a hierarchy of respect based on religious service.The most influential 5% of Al-ˤuqqāl become Ajawīd, recognized religious leaders, and from this group the spiritual leaders of the Druze are assigned. While the Shaykh al-ˤAql, which is an official position in Syria, Lebanon, and Israel, is elected by the local community and serves as the head of the Druze religious council, judges from the Druze religious courts are usually elected for this position. Unlike the spiritual leaders, the Shaykh al-ˤAql's authority is local to the country he is elected in, though in some instances spiritual leaders are elected to this position.

The Druze believe in the unity of God, and are often known as the "People of Monotheism" or simply "Monotheists". Their theology has a Neo-Platonic view about how God interacts with the world through emanations and is similar to some gnostic and other esoteric sects. Druze philosophy also shows Sufi influences.

Druze principles focus on honesty, loyalty, filial piety, altruism, patriotic sacrifice, and monotheism. They reject tobacco smoking, alcohol, consumption of pork and marriage to non-Druze. Also, in contrast to most Islamic sects, the Druze reject polygamy, believe in reincarnation, and are not obliged to observe most of the religious rituals. The Druze believe that rituals are symbolic and have an individualistic effect on the person, for which reason Druze are free to perform them or not. The community does celebrate Eid al-Adha, however, considered their most significant holiday.

Origins of the Druze people

Ethnic origins

The Druze faith extended to many areas in the Middle East, but most of the surviving modern Druze can trace their origin to the Wadi al-Taym in South Lebanon, which is named after an Arab tribe Taym-Allah (formerly Taym-Allat) which, according to the greatest Arab historian, al-Tabari, first came from Arabia into the valley of the Euphrates where they were Christianized prior to their migration into the Lebanon. Many of the Druze feudal families whose genealogies have been preserved by the two modern Syrian chroniclers Haydar al-Shihabi and al-Shidyaq seem also to point in the direction of this origin. Arabian tribes emigrated via the Persian Gulf and stopped in Iraq on the route that was later to lead them to Syria. The first feudal Druze family, the Tanukh family, which made for itself a name in fighting the Crusaders, was, according to Haydar al-Shihabi, an Arab tribe from Mesopotamia where it occupied the position of a ruling family and was apparently Christianized.[30]

The Tanukhs must have left Arabia as early as the second or third century A.D. The Ma‘an tribe, which superseded the Tanukhs and produced the greatest Druze hero in history, Fakhr-al-Din, had the same traditional origin. The Talhuq family and ‘Abd-al-Malik, who supplied the later Druze leadership, have the same record as the Tanukhs. The Imad family is named for al-Imadiyyah, near Mosul in northern Iraq, and, like the Jumblatts, is thought to be of Kurdish origin. The Arsalan family claims descent from the Hirah Arab kings, but the name Arsalan (Persian and Turkish for lion) suggests Persian influence if not origin.[30]

The most accepted theory is that the Druzes are a mixture of stocks in which the Arab largely predominates while being grafted onto an original mountain population of Aramaic blood.[65]

Nevertheless, many scholars formed their own hypotheses: for example, Lamartine (1835) discovered in the modern Druzes the remnants of the Samaritans[66]; Earl of Carnarvon (1860), those of the Cuthites whom Esarhaddon transplanted into Palestine[67]; Professor Felix von Luschan (1911), according to his conclusions from anthropometric measurements, makes the Druze, Maronites, and Alawites of Syria, together with the Armenians, Bektashis, ‘Ali-Ilahis, and Yezidis of Asia Minor and Persia, the modern representatives of the ancient Hittites.[68]

During the 18th century, there were two branches of Druze living in Lebanon: the Yemeni Druze, headed by the Hamdan and Al-Atrash families; and the Kaysi Druze, headed by the Jumblat and Arsalan families.

The Hamdan family was banished from Mount Lebanon following the battle of Ain Dara in 1711. This battle was fought between two Druze factions: the Yemeni and the Kaysi. Following their dramatic defeat, the Yemeni faction migrated to Syria in the Jebel-Druze region and its capital, Soueida. However, it has been argued that these two factions were of political nature rather than ethnic, and had both Christian and Druze supporters.

Genetics

In a 2005 study of ASPM gene variants, Mekel-Bobrov et al. found that the Israeli Druze people of the Carmel region have among the highest rate of the newly evolved ASPM haplogroup D, at 52.2% occurrence of the approximately 6,000-year-old allele.[69] While it is not yet known exactly what selective advantage is provided by this gene variant, the haplogroup D allele is thought to be positively selected in populations and to confer some substantial advantage that has caused its frequency to rapidly increase.

According to DNA testing, Druze are remarkable for the high frequency (35%) of males who carry the Y-chromosomal haplogroup L, which is otherwise uncommon in the Mideast (Shen et al. 2004).[70] This haplogroup originates from prehistoric South Asia.

Cruciani in 2007 found E1b1b1a2 (E-V13) [one from Sub Clades of E1b1b1a1 (E-V12)] in high levels (>10% of the male population) in Turkish Cypriot and Druze Arab lineages. Recent genetic clustering analyses of ethnic groups are consistent with the close ancestral relationship between the Druze and Cypriots, and also identified similarity to the general Syrian and Lebanese populations, as well as a variety of Jewish lineages (Ashkenazi, Sephardi, Iraqi, and Moroccan)(Behar et al 2010)[71].

Also, a new study concluded that the Druze harbor a remarkable diversity of mitochondrial DNA lineages that appear to have separated from each other thousands of years ago. But instead of dispersing throughout the world after their separation, the full range of lineages can still be found within the Druze population.[72]

The researchers noted that the Druze villages contained a striking range of high frequency and high diversity of the X haplogroup, suggesting that this population provides a glimpse into the past genetic landscape of the Near East at a time when the X haplogroup was more prevalent.[72]

These findings are consistent with the Druze oral tradition, that claims that the adherents of the faith came from diverse ancestral lineages stretching back tens of thousands of years.[72]

See also

- List of Druze

- Neoplatonism and Gnosticism

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Danna, Nissim (December 2003). The Druze in the Middle East: Their Faith, Leadership, Identity and Status. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. pp. 227. ISBN 978-1903900369. http://books.google.com/?id=2nCWIsyZJxUC&pg=PA99&lpg=PA99&dq=druze+population+lebanon&q=druze%20population%20lebanon.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Localities and Population, by District, Sub-District, Religion and Population Group" (PDF). Statistical Abstract of Palestine 2006. Palestine Central Bureau of Statistics. http://www1.cbs.gov.il/shnaton57/st02_07x.pdf.

- ↑ Lebanon - International Religious Freedom Report 2008 U.S. Department of State. Retrieved on 2009-09-04.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Press Release: The Druze Population of Israel" (DOC). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 2009-04-23. http://www.cbs.gov.il/www/hodaot2009n/11_09_077b.doc. (Hebrew)

- ↑ US State Department International Religious Freedom Report 2005

- ↑ Institute of Druze Studies - Druze Traditions

- ↑ "Druze Population of Australia by Place of Usual Residence (2006)". Australian Bureau of Statistics. http://www.abs.gov.au/CDataOnline. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ↑ http://www.ismaili.net/heritage/node/10766

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Swayd, Samy (1998). The Druzes: An Annotated Bibliography. Kirkland, WA, USA: ISES Publications. ISBN 0966293207.

- ↑ israwi, Najib (in Arabic). Al-Maðhab at-Tawḥīdī ad-Durzī. Brazil. pp. 66.

- ↑ Druze

- ↑ Institute of Druze Studies: Druzes

- ↑ Dana, Nissim (2003). The Druze in the Middle East: Their Faith, Leadership, Identity and Status. Sussex University Press. pp. 99. ISBN 1903900360. http://books.google.com/?id=2nCWIsyZJxUC&pg=PA99&lpg=PA99&dq=druze+population+lebanon.

- ↑ Rabah Halabi, Citizens of equal duties—Druze identity and the Jewish State, p. 55 (Hebrew)

- ↑ "Druze set to visit Syria". BBC News Online. 2004-08-30. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/3612002.stm. Retrieved 2006-09-08. "Around 80,000 Druze live in Israel, including 18,000 in the Golan Heights."

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 "About the Faith of The Mo’wa’he’doon Druze" by Moustafa F. Moukarim

- ↑ 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica, page 606

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Al-Najjar, ‘Abdullāh (1965) (in Arabic). Madhhab ad-Durūz wa t-Tawḥīd (The Druze Sect and Unism). Egypt: Dār al-Ma‘ārif.

- ↑ Hitti, Philip K (2007) [1924]. Origins of the Druze People and Religion, with Extracts from their Sacred Writings (New Edition). Columbia University Oriental Studies. 28. London: Saqi. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0863566901.

- ↑ http://www.druze.com/education/DruzeLuminariesAlHakim-English-level3.pdf

- ↑ 01. Islam | Ismaili.NET - Heritage F.I.E.L.D

- ↑ Melville's Clarel and the Intersympathy of Creeds by William Potter page 156

- ↑ Minorities in the Middle East: A History of Struggle and Self-expression by Mordechai Nisan page 95

- ↑ The Druze in the Middle East: Their Faith, Leadership, Identity and Status, Nissim Dana

- ↑ Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia by Josef W. Meri, Jere L. Bacharach.published by Routledge (2006), ISBN 0415966906

- ↑ The Olive and the Tree: The Secret Strength of the Druze by Dr Ruth Westheimer and Gil Sedan

- ↑ Swayd, Sami (2006). Historical dictionary of the Druzes. Historical dictionaries of peoples and cultures. 3. Maryland USA: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810853329

- ↑ M. Th. Houtsma, E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936

- ↑ http://www.druzeheritage.org/dhf/Druze_History.asp

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 30.6 30.7 30.8 30.9 Origins of the Druze People and Religion, by Philip K. Hitti, 1924

- ↑ Druze History

- ↑ Antoine Abraham, "Lebanese Communal Relations", Muslim World 1977 67(2): 91-105

- ↑ The Druzes and the Maronites under the Turkish Rule from 1840 to 1860, Charles Churchill published in 1862

- ↑ http://www.syrianhistory.com/node/3379

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=ecTTlytIjswC&pg=PA41

- ↑ "Shishakli and the Druzes: Integration and Intransigence"

- ↑ Dossier: Nasrallah Boutros Sfeir (May 2003)

- ↑ Identity Repertoires among Arabs in Israel, Muhammad Amara and Izhak Schnell; Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Vol. 30, 2004

- ↑ http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Society_&_Culture/druze.html

- ↑ http://www.jcpa.org/jl/hit06.htm

- ↑ http://www.myjewishlearning.com/israel/Contemporary_Life/Society_and_Religious_Issues/Arab-Israelis/druze.shtml

- ↑ Pace, Eric (1993-10-05). "Sheik Amin Tarif, Arab Druse Leader In Israel, Dies at 95". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1993/10/05/obituaries/sheik-amin-tarif-arab-druse-leader-in-israel-dies-at-95.html. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- ↑ Firro, Kais (2006-08-15). "Druze Herev Battalion Fights 32 Days With No Casualties". Israel National News. http://www.israelnn.com/news.php3?id=110102.

- ↑ Elections 2009 / Druze likely to comprise 5% of next Knesset, despite small population

- ↑ Christensen, John (Saturday, November 15, 2008). "Consul General is an Arab Who Represents Israel Well". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. http://www.ajc.com/services/content/printedition/2008/11/15/mansour.html. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ↑ Stern, Yoav. "Druze, Circassian forum: Israel should remain a Jewish state". Ha'aretz. http://www.haaretz.com/news/druze-circassian-forum-israel-should-remain-a-jewish-state-1.214417. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 "Islam Religious Leader Commits to Noahide "Seven Laws of Noah"". Institute of Noahide Code. http://www.noahide.org/article.asp?Level=128&Parent=342. Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- ↑ UN

- ↑ UN.

- ↑ Scott Wilson (2006-10-30). "Golan Heights Land, Lifestyle Lure Settlers". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/10/29/AR2006102900926.html. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ↑ Fear and tranquility on the Golan

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 A would-be happy link with Syria The Economist Feb 19th 2009

- ↑ Ynet

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Golan's Druse Wary of Israel and Syria June 3, 2007

- ↑ The Independent

- ↑ The Golan’s Druze wonder what is best

- ↑ ICRC.org

- ↑ Damascus-online.com

- ↑ Central Elections Committee, Results of the elections for the 18th Knesset (eligible voters in column D). For age structure, see CBS.gov.il publications. For population, see CBS.gov.il Ishuvim

- ↑ The Druze Faith by Sami Nasib Makarem

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 61.3 Druze Spirituality and Asceticism By Dr. Samy Swayd, SDSU (An abridged rough draft)

- ↑ BBC - h2g2 - The Druze

- ↑ "The Epistle Answering the People of Esotericism" (batinids), Epistles of Wisdom, Second Volume (a rough translation from the Arabic version)

- ↑ Origins of the Druze People and Religion, by Philip K. Hitti, published in 1924, page 51.

- ↑ "1911 Encyclopedia Britannica, DRUSES, or DRUZES (Arab. Druz)". http://encyclopedia.jrank.org/DRO_ECG/DRUSES_or_DRUZES_Arab_Druz_.html. "There is good reason to regard the Druses as, racially, a mixture of refugee stocks, in which the Arab largely predominates, grafted on to an original mountain population of Aramaic blood."

- ↑ Voyage, by Lamartine, II, page 109.

- ↑ Recollections of the Druses of Lebanon (London, 1860), pp. 42-43.

- ↑ Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (London, 1911), page 241.

- ↑ "Ongoing Adaptive Evolution of ASPM, a Brain Size Determinant in Homo sapiens", Science, 9 September 2005: Vol. 309. no. 5741, pp. 1720-1722.

- ↑ http://evolutsioon.ut.ee/publications/Shen2004.pdf

- ↑ [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/vaop/ncurrent/pdf/nature09103.pdf "The genome-wide structure of the Jewish people".

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 American Technion Society (2008, May 12). Genetics Confirm Oral Traditions Of Druze In Israel, ScienceDaily.

Further reading

- Sakr Abu Fakhr: "Voices from the Golan"; Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 29, No. 4 (Autumn, 2000), pp. 5–36.

- Rabih Alameddine: I, the Divine: A Novel in First Chapters, Norton (2002). ISBN 0-393-32356-0.

- B. Destani, ed.: Minorities in the Middle East: Druze Communities 1840–1974, 4 volumes, Slough: Archive Editions (2006). ISBN 1840971657.

- R. Scott Kennedy: "The Druze of the Golan: A Case of Non-Violent Resistance"; Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Winter, 1984), pp. 48–6.

- Dr. Anis Obeid: The Druze & Their Faith in Tawhid, Syracuse University Press (July 2006). ISBN 0815630972.

- Shmuel Shamai: "Critical Sociology of Education Theory in Practice: The Druze Education in the Golan"; British Journal of Sociology of Education, Vol. 11, No. 4 (1990), pp. 449–463.

- Samy Swayd: The Druzes: An Annotated Bibliography, Kirkland, Washington: ISES Publications (1998). ISBN 0966293207.

- Bashar Tarabieh: "Education, Control and Resistance in the Golan Heights"; Middle East Report, No. 194/195, Odds against Peace (May–Aug., 1995), pp. 43–47.

External links

Sources

- History and sites of the Druze

- Rise and fall of the Syrian Druze

- Institute of Druze Studies, San Diego, California

- Druzenet, English publications

- Druse, Druze, Mowahhidoon described at the OCRT site

- Druze Catechism

- 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica article

- Article about Druze Encyclopedia Britannica Concise

- Longer article about Druze Encyclopedia Britannica Concise

- Druze by Pam Rohland

- SEMP - Who are the Druze?

- Druze articles

- Who are the Druze? Photo essay on PBS Wide Angle website

Communities

- Druze Chat

- Druze Faces

- Druze News Druze News from Lebanon, Israel and the Druze world.

- Lebanese Druze Online Community

- American Druze Society - National

- American Druze Society - Michigan

- The Druze Association of Edmonton

- Canadian Druze Society

- Australian Druze Community

- South Australian Druze Community

- Israeli Druze Online - in Hebrew

- European Druze Society

- Meeting Druze from all over the world

Other links

- Staying Druze in America video on PBS Wide Angle website

- Druze: A small peace of Israel from hackwriters.com

- The Druzes and the Maronites under the Turkish Rule from 1840 to 1860. Cornell University Library Historical Monographs Collection. ISBN 1-429-73982-7.

- Contestant No. 2 PBS Wide Angle documentary about a Druze teen who challenges her conservative community

- Druze in Israel and Syria

- The Druze by Dr. Naim Aridi

- Historical Changes in the Political Role of the Druze in Lebanon by Dr. Abbas Abu Saleh

- The Druze

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||