Dot product

In mathematics, the dot product is an algebraic operation that takes two equal-length sequences of numbers (usually coordinate vectors) and returns a single number obtained by multiplying corresponding entries and adding up those products. The name is derived from the centered dot "·" that is often used to designate this operation; the alternative name scalar product emphasizes the scalar (rather than vector) nature of the result.

The principal use of this product is the inner product in a Euclidean vector space: when two vectors are expressed on an orthonormal basis, the dot product of their coordinate vectors gives their inner product. For this geometric interpretation, scalars must be taken to be real numbers; while the dot product can be defined in a more general setting (for instance with complex numbers as scalars) many properties would be different. The dot product contrasts (in three dimensional space) with the cross product, which produces a vector as result.

Contents |

Definition

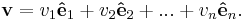

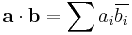

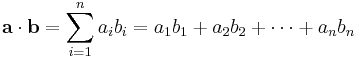

The dot product of two vectors a = [a1, a2, ... , an] and b = [b1, b2, ... , bn] is defined as:

where Σ denotes summation notation and n is the dimension of the vector space.

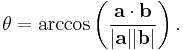

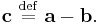

In dimension 2, the dot product of vectors [a,b] and [c,d] is ac + bd. Similarly, in a dimension 3, the dot product of vectors [a,b,c] and [d,e,f] is ad + be + cf. For example, the dot product of two three-dimensional vectors [1, 3, −5] and [4, −2, −1] is

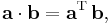

The dot product can also be obtained via transposition and matrix multiplication as follows:

where both vectors are interpreted as column vectors, and aT denotes the transpose of a, in other words the corresponding row vector.

Geometric interpretation

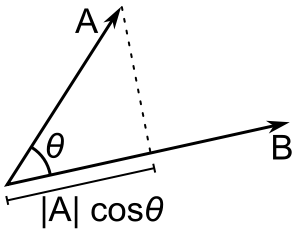

|A| cos(θ) is the scalar projection of A onto B.

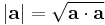

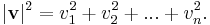

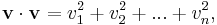

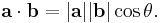

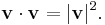

In Euclidean geometry, the dot product, length, and angle are related. For a vector a, the dot product a · a is the square of the length of a, or

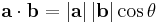

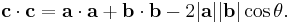

where |a| denotes the length (magnitude) of a. More generally, if b is another vector

where |a| and |b| denote the length of a and b and θ is the angle between them.

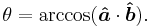

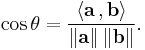

This formula can be rearranged to determine the size of the angle between two nonzero vectors:

One can also first convert the vectors to unit vectors by dividing by their magnitude:

then the angle θ is given by

The terminal points of both unit vectors lie on the unit circle. The unit circle is where the trigonometric values for the six trig functions are found. After substitution, the first vector component is cosine and the second vector component is sine, i.e. (cos x, sin x) for some angle x. The dot product of the two unit vectors then takes <cos x, sin x><cos y, sin y> for angles x, y and returns (cos x)(cos y) + (sin x)(sin y) = cos(x − y) where x − y = theta.

As the cosine of 90° is zero, the dot product of two orthogonal vectors is always zero. Moreover, two vectors can be considered orthogonal if and only if their dot product is zero, and they have non-null length. This property provides a simple method to test the condition of orthogonality.

Sometimes these properties are also used for defining the dot product, especially in 2 and 3 dimensions; this definition is equivalent to the above one. For higher dimensions the formula can be used to define the concept of angle.

The geometric properties rely on the basis being orthonormal, i.e. composed of pairwise perpendicular vectors with unit length.

Scalar projection

If both a and b have length one (i.e., they are unit vectors), their dot product simply gives the cosine of the angle between them.

If only b is a unit vector, then the dot product a · b gives |a| cos(θ), i.e., the magnitude of the projection of a in the direction of b, with a minus sign if the direction is opposite. This is called the scalar projection of a onto b, or scalar component of a in the direction of b (see figure). This property of the dot product has several useful applications (for instance, see next section).

If neither a nor b is a unit vector, then the magnitude of the projection of a in the direction of b, for example, would be a · (b / |b|) as the unit vector in the direction of b is b / |b|.

Rotation

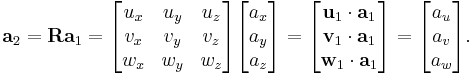

A rotation of the orthonormal basis in terms of which vector a is represented is obtained with a multiplication of a by a rotation matrix R. This matrix multiplication is just a compact representation of a sequence of dot products.

For instance, let

- B1 = {x, y, z} and B2 = {u, v, w} be two different orthonormal bases of the same space R3, with B2 obtained by just rotating B1,

- a1 = (ax, ay, az) represent vector a in terms of B1,

- a2 = (au, av, aw) represent the same vector in terms of the rotated basis B2,

- u1, v1, w1 be the rotated basis vectors u, v, w represented in terms of B1.

Then the rotation from B1 to B2 is performed as follows:

Notice that the rotation matrix R is assembled by using the rotated basis vectors u1, v1, w1 as its rows, and these vectors are unit vectors. By definition, Ra1 consists of a sequence of dot products between each of the three rows of R and vector a1. Each of these dot products determines a scalar component of a in the direction of a rotated basis vector (see previous section).

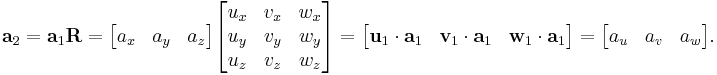

If a1 is a row vector, rather than a column vector, then R must contain the rotated basis vectors in its columns, and must post-multiply a1:

Physics

In physics, magnitude is a scalar in the physical sense, i.e. a physical quantity independent of the coordinate system, expressed as the product of a numerical value and a physical unit, not just a number. The dot product is also a scalar in this sense, given by the formula, independent of the coordinate system. Example:

- Mechanical work is the dot product of force and displacement vectors.

- Magnetic flux is the dot product of the magnetic field and the area vectors.

Properties

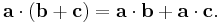

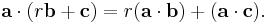

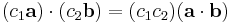

The following properties hold if a, b, and c are real vectors and r is a scalar.

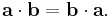

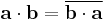

The dot product is commutative:

The dot product is distributive over vector addition:

The dot product is bilinear:

When multiplied by a scalar value, dot product satisfies:

(these last two properties follow from the first two).

Two non-zero vectors a and b are perpendicular if and only if a • b = 0.

Unlike multiplication of ordinary numbers, where if ab = ac, then b always equals c unless a is zero, the dot product does not obey the cancellation law:

- If a • b = a • c and a ≠ 0, then we can write: a • (b − c) = 0 by the distributive law; the result above says this just means that a is perpendicular to (b − c), which still allows (b − c) ≠ 0, and therefore b ≠ c.

Provided that the basis is orthonormal, the dot product is invariant under isometric changes of the basis: rotations, reflections, and combinations, keeping the origin fixed. The above mentioned geometric interpretation relies on this property. In other words, for an orthonormal space with any number of dimensions, the dot product is invariant under a coordinate transformation based on an orthogonal matrix. This corresponds to the following two conditions:

- The new basis is again orthonormal (i.e., it is orthonormal expressed in the old one).

- The new base vectors have the same length as the old ones (i.e., unit length in terms of the old basis).

If a and b are functions, then the derivative of a • b is a' • b + a • b'

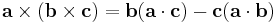

Triple product expansion

This is a very useful identity (also known as Lagrange's formula) involving the dot- and cross-products. It is written as

which is easier to remember as "BAC minus CAB", keeping in mind which vectors are dotted together. This formula is commonly used to simplify vector calculations in physics.

Proof of the geometric interpretation

Consider the element of Rn

Repeated application of the Pythagorean theorem yields for its length |v|

But this is the same as

so we conclude that taking the dot product of a vector v with itself yields the squared length of the vector.

- Lemma 1

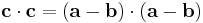

Now consider two vectors a and b extending from the origin, separated by an angle θ. A third vector c may be defined as

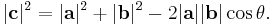

creating a triangle with sides a, b, and c. According to the law of cosines, we have

Substituting dot products for the squared lengths according to Lemma 1, we get

(1)

(1)

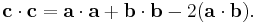

But as c ≡ a − b, we also have

,

,

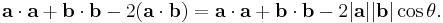

which, according to the distributive law, expands to

(2)

(2)

Merging the two c • c equations, (1) and (2), we obtain

Subtracting a • a + b • b from both sides and dividing by −2 leaves

Generalization

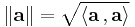

The inner product generalizes the dot product to abstract vector spaces and is usually denoted by  . Due to the geometric interpretation of the dot product the norm ||a|| of a vector a in such an inner product space is defined as

. Due to the geometric interpretation of the dot product the norm ||a|| of a vector a in such an inner product space is defined as

such that it generalizes length, and the angle θ between two vectors a and b by

In particular, two vectors are considered orthogonal if their inner product is zero

For vectors with complex entries, using the given definition of the dot product would lead to quite different geometric properties. For instance the dot product of a vector with itself can be an arbitrary complex number, and can be zero without the vector being the zero vector; this in turn would have severe consequences for notions like length and angle. Many geometric properties can be salvaged, at the cost of giving up the symmetric and bilinear properties of the scalar product, by alternatively defining

where bi is the complex conjugate of bi. Then the scalar product of any vector with itself is a non-negative real number, and it is nonzero except for the zero vector. However this scalar product is not linear in b (but rather conjugate linear), and the scalar product is not symmetric either, since

.

.

This type of scalar product is nevertheless quite useful, and leads to the notions of Hermitian form and of general inner product spaces.

The Frobenius inner product generalizes the dot product to matrices. It is defined as the sum of the products of the corresponding components of two matrices having the same size.

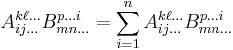

Generalization to tensors

The dot product between a tensor of order n and a tensor of order m is a tensor of order n+m-2. The dot product is calculated by multiplying and summing across a single index in both tensors. If  and

and  are two tensors with element representation

are two tensors with element representation  and

and  the elements of the dot product

the elements of the dot product  are given by

are given by

This definition naturally reduces to the standard vector dot product when applied to vectors, and matrix multiplication when applied to matrices.

Occasionally, a double dot product is used to represent multiplying and summing across two indices. The double dot product between two 2nd order tensors is a scalar.

See also

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Dot product" from MathWorld.

- A quick geometrical derivation and interpretation of dot product

- Interactive GeoGebra Applet

- Java demonstration of dot product

- Another Java demonstration of dot product

- Explanation of dot product including with complex vectors

- "Dot Product" by Bruce Torrence, Wolfram Demonstrations Project, 2007.

|

|||||

![[1, 3, -5] \cdot [4, -2, -1]

= 1 \times 4 + 3 \times (-2) + (-5) \times (-1)

= 4 - 6 + 5

= 3.](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/787bc8a894abfa4a37ec49fe2e372c2a.png)